Stigmata

Jennifer C. Lane, “Stigmata,” in Finding Christ in the Covenant Path: Ancient Insights for Modern Life (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 153‒70.

We often think of knowledge as information in our mind, but there is an older sense of knowing that points to what we have become through our experience. When the Lord said, “This is life eternal, that they might know thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent” (John 17:3), he wasn’t promising eternal life to those who have the biggest information database about God. Knowing in this context is connected to becoming.[1]

In the spring of 2005, I learned something about knowledge and becoming. I attended a professional conference that happened to take place during the last days of Pope John Paul II’s life. My return trip included a long layover in Atlanta, where I spent several hours watching the funeral on a CNN broadcast. As I watched the celebration of the funeral Mass, I reflected on the ease and naturalness with which Cardinal Ratzinger—soon to become Pope Benedict XVI—officiated. I had grown up down the street from a large Catholic high school and had attended Mass with my friends from the neighborhood, but the mammoth scale of this funeral Mass invited attention.

As I watched that airport television monitor, I reflected on the kind of knowledge that was on display in the ritual actions of the celebration of the Mass: a knowledge of what to do, how to hold oneself. This liturgical action represented a kind of embodied knowledge. This was action without thought in the sense that it was natural, embodied. It was what the individual was. In watching it, I wondered what would be involved in learning this and what it would mean to the one who embodied it.

The embodiment of knowledge I observed as an outsider caused me to reflect on knowledge and how it is conveyed in ritual and ordinance. The possibility of coming to a knowledge of God is repeated throughout the scriptures. I believe that our contemporary understanding of knowledge as acquiring a body of information is a tremendous barrier in understanding and receiving a fulfillment of those promises.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks discusses the more ancient concept of knowledge in his classic talk “The Challenge to Become.” He observes that “the Apostle Paul taught that the Lord’s teachings and teachers were given that we may all attain ‘the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ’ (Ephesians 4:1). This process requires far more than acquiring knowledge. It is not even enough for us to be convinced of the gospel; we must act and think so that we are converted by it. In contrast to the institutions of the world, which teach us to know something, the gospel of Jesus Christ challenges us to become something.”[2] I believe that knowledge as it is referred to in the language of scripture differs from that acquired in the “institutions of the world.”

Knowledge in a scriptural sense is not what we know, but what we are, what we have become. Knowledge is knowing how to do things, how to be in situations. This knowledge is not abstract but embodied, and it is modeled for us in the ritual action of ordinances. The ordinances point to a way of being that we can achieve through the process of conversion; they model a way of being in which we know God.

It can be challenging for us to think of ordinances as a way of conveying knowledge. The symbols and nonverbal communication of the ordinances do not fit our contemporary model of what knowledge is. Here again, the images of the Middle Ages can bridge our modern ways of thinking with ancient concepts that the scriptures and ordinances present us with.

Embodying the Image of Christ

In the later Middle Ages, the idea of becoming like Christ was seen to be most fully exemplified in the life of St. Francis of Assisi. After a worldly youth, he experienced a conversion to Christ that led him to reject the status, riches, and power available to him through his wealthy family. Instead, he chose to follow Christ by serving in degrading conditions, caring for lepers and the poor. He lived to glorify Christ in all that he did.

As the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, Francis gave up his expensive clothes as a symbol of his rejection of worldly values, visible status, and prestige. He and his followers “were satisfied with a single tunic, often patched inside and out. Nothing about it was refined, rather it appeared lowly and rough so that in it they seemed completely crucified to the world”[3]—his biographer’s reference to Galatians 6:14: “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world.”

St. Francis was believed to have been changed into the image of Christ through hislife of discipleship and his response of love beholding Christ’s suffering. Kruisdoodvan Christus met stigmatisatie van Franciscus, end of the fifteenth century. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

St. Francis was believed to have been changed into the image of Christ through hislife of discipleship and his response of love beholding Christ’s suffering. Kruisdoodvan Christus met stigmatisatie van Franciscus, end of the fifteenth century. Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht.

An example of Francis’s willingness to serve and identify with the poor as a means of identifying with Christ is captured in this quotation given by his biographer, Thomas of Celano: “He used to say: ‘Anyone who curses the poor insults Christ whose noble banner the poor carry, since Christ made himself poor for us in this world.’” The biographer connects that view of Christ to Francis’s life of service. “That is also why, when he met poor people burdened with wood or other heavy loads, he would offer his own weak shoulders to help them.”[4]

Bonaventure, a later biographer, explains Francis’s emphasis on becoming poor—his practice of asceticism was not merely to deprive the body, but to conform himself to the crucified Christ by crucifying the “flesh with its passions and desires.”[5] Francis’s poverty was an imitation of Christ because “poverty was the close companion of the Son of God” [6] and because “this is the royal dignity which the Lord Jesus assumed when he became poor for us that he might enrich us by his poverty.”[7] Poverty was participation. Francis submitted to the “mortification” of giving up his wealthy apparel in order to “carry externally in his body the cross of Christ.”[8] Francis did all of this in the imitation of Christ and in memory of Christ’s sacrifice, living out Christ’s example of servanthood and ministering. Because of this imitation, within the Franciscan tradition Francis is described as an alter Christus, another Christ.

As an outward sign of the inward reality of who he had become in following the example of Christ, Francis was understood to have received the stigmata, the marks of the wounds of Christ, in his own body. The life that he lived following Christ changed him. Francis’s love for Christ and his imitation of Christ’s humility and service was understood to have changed him into Christ’s image. Bonaventure recorded that Francis was changed into the image of Christ because beholding him “fastened to a cross pierced his soul with a sword of compassionate sorrow.”[9] All that Francis did and became was a response to the love of Christ manifest in his suffering and death.

We don’t need to come to any conclusion about the historical experience of Francis to appreciate the symbolic power of the stigmata. The image and idea of the stigmata are powerful to contemplate, whether or not we can know what really happened to him. Depictions of St. Francis with the stigmata were spread throughout Europe in the later Middle Ages, and his image communicated the message that the ideal of imitating Christ was possible. St. Francis was an exemplar of knowing Christ in the sense of following him and, thus, becoming like him.

The idea of knowing as becoming can be understood as embodied knowledge, being both spiritually and physically changed through following Christ. This can be seen in Alma’s questions: “Have ye spiritually been born of God? Have ye received his image in your countenances?” (Alma 5:14). We usually read countenance as referring to the face alone, but in the nineteenth century, it primarily meant “the whole figure or outside appearance.”[10] In this way, we can see Alma asking about our being, our way of living. Alma’s sense of how deeply our whole selves can be transformed by Christ comes out later in the chapter when he asks, “Can you look up, having the image of God engraven upon your countenances?” (Alma 5:19). The verb engrave emphasizes how deeply we can receive Christ’s image in our countenance.

The stigmata of St. Francis exemplifies the idea of being both spiritually and physically

The stigmata of St. Francis exemplifies the idea of being both spiritually and physically

changed by following Christ. Christus als Schmerzensmann, hl. Franzikskusund Stifterpaar, around 1420. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

Like Francis, Paul also spoke of how he was changed by focusing entirely on Christ, “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world” (Galatians 6:14). We may not know exactly what he meant, but shortly after this Paul says, “From henceforth let no man trouble me: for I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus” (6:17). The Greek for “marks” is stigmata. Paul’s body as well as his spirit had come to a knowledge of the Savior.

King Benjamin also teaches how we are changed by serving the Lord. In Mosiah 5 we can see the embodied knowledge that comes through being Christ’s servants: “For how knoweth a man the master whom he has not served, and who is a stranger unto him, and is far from the thoughts and intents of his heart?” (Mosiah 5:13). As we seek to follow and serve Christ, we come to know him. Mormon looked ahead to what we can become by continuing on this covenant path. He testified that through this process of becoming true followers of Christ and being filled with his love we take on his image: “when he shall appear we shall be like him for we shall see him as he is; that we may have this hope; that we may be purified even as he is pure” (Moroni 7:48).

President Gordon B. Hinckley taught that our responsibility to take Christ’s name and image upon ourselves is not something for a future day. Instead, it is part of our covenant to reflect Christ’s image to the world. Our lives and choices must reflect his life and light to the world. “As His followers, we cannot do a mean or shoddy or ungracious thing without tarnishing His image. Nor can we do a good and gracious and generous act without burnishing more brightly the symbol of Him whose name we have taken upon ourselves. And so our lives must become a meaningful expression, the symbol of our declaration of our testimony of the Living Christ, the Eternal Son of the Living God.”[11] Our lives are the symbol of our faith. Part of taking the name of Christ upon us is the responsibility of being a living witness of his living reality.

Ordinances and Embodying Christ

Simply wanting to follow and imitate Christ will not be enough; wanting to know him will not be enough. One of the great blessings of the Restoration is covenant access to Christ’s power to transform us. The ordinances show us how and, I believe, enable us to “put on Christ” (Galatians 3:27). Returning to Elder Oaks’s words, “The Lord’s teachings and teachers were given that we may all attain ‘the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ’ (Ephesians 4:13). . . . It is not even enough for us to be convinced of the gospel; we must act and think so that we are converted by it.”[12] Having a testimony and feeling Christ’s love can convince us of the truthfulness of the gospel, but that kind of knowing will not be enough.

We need to become, and we need power to become more than we are by ourselves. The invitation is to grow into the “measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ.” Receiving the ordinances alone cannot substitute for taking on “the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ” and true conversion, becoming like him, but they do put us on the path. An important way that the ordinances do this is by modeling this new way of being. Additionally, through covenant, the ordinances empower us to become what we promise to become. We can see this ritual embodiment of Christ in baptism and other ordinances.

In the ordinances, we “put on Christ,” and participate in his life and his atoning sacrifice. Through our ritual action, we embody how Christ was in the world. We are all familiar with the explanation, clearly elaborated in Paul’s writings, that in baptism by immersion we symbolically die, are buried, and are resurrected with Christ.

In Galatians 3:27, Paul says, “For as many of you as have been baptized into Christ have put on Christ.” Paul explains how we put on Christ in baptism. When we are “baptized into Jesus Christ [we] were baptized into his death” (Romans 6:3). Our immersion is a participation in his death. Then after “we are buried with him by baptism into death,” we also participate in his resurrection, “that like as Christ was raised up from the dead by the glory of the Father, even so we also should walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4).

The ordinance of baptism allows us to ritually put on Christ. His way of being is modeled in the ordinance of baptism. It is a submission to the will of the Father and a separation from worldliness, the death of the man of sin. The ordinance is not the end but the beginning. Paul tells the saints to live out what they have symbolically done in the ordinance of baptism: “put . . . on the Lord Jesus Christ, and make not provision for the flesh, to fulfil the lusts thereof” (Romans 13:14). We must go forward and walk in newness of life, putting on Christ in our daily life, just as we did in the ordinance.

Another explanation of how ordinances allow us to embody Christ is found in 2 Nephi 31. Nephi explains how the ordinance of baptism is an embodiment of and participation in Christ’s life because Christ’s own baptism was an embodiment of submission. Christ submitted to immersion and “according to the flesh he [humbled] himself before the Father and [witnessed] unto the Father that he would be obedient unto him in keeping his commandments” (2 Nephi 31:7).

The ordinances are the way in the sense that Christ is the Way. Baptism “showeth unto the children of men the straitness of the path, and the narrowness of the gate, by which they should enter, he having set the example before them” (2 Nephi 31:9). The submission embodied in being immersed in water models an entire life of submission—the life of Christ. “And he said unto the children of men: Follow thou me. Wherefore, my beloved brethren, can we follow Jesus save we shall be willing to keep the commandments of the Father?” (2 Nephi 31:10).

Our ritual embodiment of Christ in baptism continues in the ordinances of the temple. President Harold B. Lee commented, “The receiving of the endowment requires the assuming of obligations by covenants which in reality are but an embodiment or an unfolding of the covenants each person should have assumed at baptism.”[13] Through the ordinances, we gain a knowledge of God. Through the ordinances, we ritually embody the kind of obedience and submission that we need to develop in our lives through the process of conversion and becoming.

Charles Wesley, author of so many of our hymns, wrote one of my favorites—“Love Divine, All Loves Excelling”—that does not appear in our hymnbook. For me, the hymn captures the onward progression of coming unto Christ and receiving the power of his Atonement that we experience in the endowment. The words of this hymn often go through my mind during endowment sessions. They illuminate the gradual changes we make as we symbolically come closer and closer to God through the enabling power of Christ.

The first stanza speaks of Christ coming down with redeeming love:

Love divine, all loves excelling,

Joy of Heav’n to earth come down;

Fix in us thy humble dwelling;

All thy faithful mercies crown!

Jesus, Thou art all compassion,

Pure unbounded love Thou art;

Visit us with Thy salvation,

Enter every trembling heart.

The following verses express a prayer that Christ “take away the love of sinning” and that we might serve him as his hosts above, never leaving his temple.

The final verse points to the ongoing process through which we come to know Christ as we become like him:

Finish, then, Thy new creation;

Pure and spotless let us be;

Let us see Thy great salvation

Perfectly restored in Thee;

Changed from glory into glory,

’Til in Heav’n we take our place,

’Til we cast our crowns before Thee,

Lost in wonder, love, and praise.[14]

Becoming transformed into the image of Christ is a process. It is a journey. As we daily repent and exercise our faith in Christ, we are “changed from glory into glory,” becoming fit for God’s presence. The final result of this process is to receive of his fullness, but, as the book of Revelation says, in that day we will “fall down before him that sat on the throne, and worship him that liveth for ever and ever, and cast [our] crowns before the throne” (4:10). When we finally do arrive, we will truly be “lost in wonder, love, and praise” for his redeeming and exalting love that has re-created us in his image.

Choosing to Know Him

The ordinances point to a way of being in which we know God. They model a way of being, in which we have “the mind of Christ” (1 Corinthians 2:16). The knowledge of God that the ordinances allow us to experience through ritual embodiment leads us to a new kind of life. This is a life in which we know Christ because his Spirit is in us, helping us to want and to do what Christ would want and do. As we live out our covenants, we come to know Christ. We learn what to do, what to say, and how to live in a holy and godly manner. Through obedience and submission in ritual action, we both consent to be and learn to be in the world as Christ was. In the ordinances, we come to know Christ because we “put on Christ” through ritual embodiment (see Galatians 3:27). We participate in an embodiment of submission and willingness to obey as he did. It is not an abstract knowledge of Christ but an embodied knowledge.

The ordinances are necessary but not sufficient. We make covenants, but we also must choose to keep those covenants. We “put on Christ” in the ordinances, but we must also “put on Christ” in our lives. The covenant to obey becomes meaningful not if we see it as an obligation to save ourselves, but when we see it as a choice to more fully receive Christ into our lives. In the ordinances, we embody his submission, his obedience.

We learn to take his name and his nature upon ourselves. Christ said, “Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matthew 11:28–30). When we see the ordinances’ ritual embodiment of Christ as the means of accepting this invitation, then obedience in all aspects of our lives makes sense in light of the gospel. Obedience is not about our capacity but our willingness.

Obedience is the choice to exercise faith and submit. The submission of our will, as Elder Neal A. Maxwell so often emphasized, is the one thing we have to offer.[15] Our submission to the will of the Father is the only way we can put on Christ. In our echo of “thy will, not mine be done,” we connect ourselves with the grace of Christ. “Abide in me, and I in you. As the branch cannot bear fruit of itself, except it abide in the vine; no more can ye, except ye abide in me. I am the vine, ye are the branches: He that abideth in me, and I in him, the same bringeth forth much fruit: for without me ye can do nothing” (John 15:4–5). Putting on Christ through participating in his ordinances is accepting the invitation to know God. The ritual embodiment of Christ is accepting the invitation to eternal life because it is Christ’s life, God’s life, that we are choosing to receive.

The connection of further ordinances and the knowledge of God is made explicit in Doctrine and Covenants, section 84. “And this greater priesthood administereth the gospel and holdeth the key of the mysteries of the kingdom, even the key of the knowledge of God” (84:19) As we seek to know Christ, we must look for this knowledge in the temple ordinances of the Melchizedek Priesthood. “Therefore, in the ordinances thereof, the power of godliness is manifest” (84:20).

The ritual embodiment of the ordinances points to and empowers us for the true embodiment and true knowledge that comes through personal conversion and sanctification. “And without the ordinances thereof, and the authority of the priesthood, the power of godliness is not manifest unto men in the flesh; For without this no man can see the face of God, even the Father, and live” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:21–22). The endowment of power gives us hope that we can gradually come to know Christ. It gives us hope that we can return to his presence and receive the kind of life that he has. As we accept the invitation to “come unto Christ, and be perfected in him,” we come to know him as we become like him (Moroni 10:32–33; see Moroni 7:48).

A Renewed Invitation

When my husband and I moved to California to start doctoral work, we had a chance to live for a year in my grandfather’s house in Pasadena, in the stake where President Howard W. Hunter had been stake president. My grandfather had passed away the previous year, shortly after we were married, but the house was still owned by the family and it was a blessing to feel connected to family during that transition in our lives.

My grandfather had served on the high council under President Hunter decades before I was born, but I had heard my mother speak about it on occasion. A couple of months before we moved to Pasadena, Ezra Taft Benson passed away and President Hunter became the prophet. During the time he was prophet, President Hunter was not able to travel very much, but he did arrange to come to Pasadena. My husband and I had a chance to sing in the choir when he spoke at our stake conference, and we felt his spirit of love and his vision for the Church. Hearing him in person somehow magnified the words that he gave in his other addresses as prophet.

President Hunter was not President of the Church for even one full year. His life had been preserved, and he seemed to have one subject to talk about that everyone would hear: the temple. We also heard his invitation to “live with ever more attention to the life and example of the Lord Jesus Christ,” but may not have realized how interwoven that was with his invitation that all be worthy of a temple recommend and attend the temple as often as circumstances permit.

In his very first general conference talk as prophet, President Hunter expressed a piercing vision of the temple as a symbol of our membership. With it, he extended an invitation to “study the Master’s every teaching and devote ourselves more fully to his example.”[16] He explained that Christ “has given us ‘all things that pertain unto life and godliness.’ He has ‘called us to glory and virtue’ and has ‘given unto us exceeding great and precious promises: that by these [we] might be partakers of the divine nature’ (2 Pet. 1:3–4).” President Hunter gave his witness of those promises that Peter spoke of. “I believe in those ‘exceeding great and precious promises,’ and I invite all within the sound of my voice to claim them. We should strive to ‘be partakers of the divine nature.’” President Hunter continued, “In that spirit I invite the Latter-day Saints to look to the temple of the Lord as the great symbol of your membership.”

With this insight from a modern prophet we can look at this passage in 2 Peter and see more clearly the relationship between the temple and coming to know and become like Christ. We read in 2 Peter that Christ’s “divine power hath given unto us all things that pertain unto life and godliness, through the knowledge of him that hath called us to glory and virtue: Whereby are given unto us exceeding great and precious promises: that by these ye might be partakers of the divine nature” (1:3–4; emphasis added). President Hunter could see that we become partakers of the divine nature through the great and precious promises we receive in the temple. He could see that it was only “by these” covenant promises that we could get the “divine power” that we need to change and become what we need to become. It is only by putting on Christ through the ordinances of the temple that we come to know him. It is only by putting on Christ through the ordinances of the temple that we receive “all things that pertain unto life and godliness.”

The promises through which we become “partakers of the divine nature” are the promises in the ordinances and covenants of the temple. These promises are the way that we come to know Christ. It is only by making and keeping these covenants that we are able to receive these great and precious promises that allow us to be partakers of the divine nature. “This greater priesthood administereth the gospel and holdeth the key of the mysteries of the kingdom, even the key of the knowledge of God. Therefore, in the ordinances thereof, the power of godliness is manifest” (Doctrine and Covenants 84:19–20). Through the ordinances we receive the power to become godly.

Assisting people to come to a knowledge of God seems to be the very purpose for which the Restoration was brought about. Some may look back to the early days of the Restoration with nostalgia and long for a time when knowledge was poured out on the Saints. I believe that such a view rests on a limited understanding of knowledge.

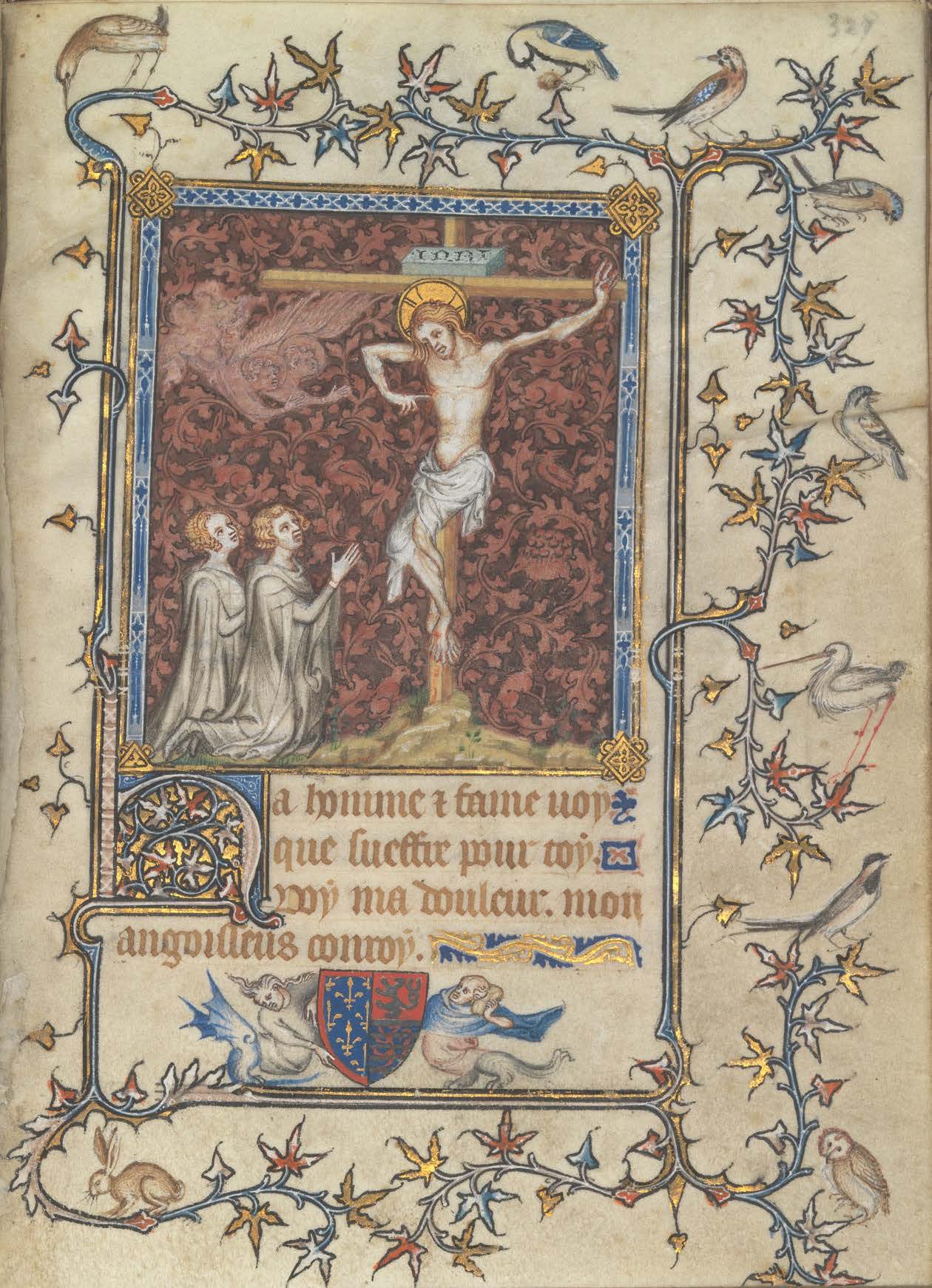

“Look unto me in every thought; doubt not, fear not. Behold the wounds which pierced my side, and also the prints of the nails in my hands and feet” (Doctrine and Covenants 6:36–37). The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, fol. 328r, before 1349. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1969.

“Look unto me in every thought; doubt not, fear not. Behold the wounds which pierced my side, and also the prints of the nails in my hands and feet” (Doctrine and Covenants 6:36–37). The Prayer Book of Bonne of Luxembourg, Duchess of Normandy, fol. 328r, before 1349. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1969.

With a broader sense of knowledge as embodied, both in ordinance and in converted lives, I believe that now is the time when the knowledge of God is positioned to be poured out more than at any other time in history. I believe that through the expansion of the Church and the building of temples throughout the earth, we are seeing the beginning of the fulfillment of Jeremiah’s prophecy.

Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel. . . . After those days, saith the Lord, I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people. And they shall teach no more every man his neighbour, and every man his brother, saying, Know the Lord: for they shall all know me, from the least of them unto the greatest of them, saith the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more. (Jeremiah 31:31–34; emphasis added)

Elder Oaks observes that “in contrast to the institutions of the world, which teach us to know something, the gospel of Jesus Christ challenges us to become something.” As Latter-day Saints we should not look only for intellectual knowledge that comes in a form understandable to the “institutions of the world,” even if it were to include information that we may feel we need to respond to questions about or criticisms of the Church. We should not be disheartened because there are not new sections added to the Doctrine and Covenants.

The knowledge of God is available. The “key of the knowledge of God” has been restored (Doctrine and Covenants 84:19). “Therefore, in the ordinances thereof, the power of godliness is manifest” (84:20). The ordinances were “given that we may all attain ‘the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ.’” As we live out our covenants, we grow into that knowledge. As we attain the “stature of the fulness of Christ” (Ephesians 4:13), we will know God because we will have become like him (see 1 John 3:1–6; Moroni 7:48).

Notes

[1] Some components of this chapter on embodied knowledge appeared earlier in my “Embodied Knowledge of God,” Element: A Journal of Mormon Philosophy and Theology 2, no. 1 (2006): 61–71. Other sections on St. Francis appeared earlier in my “I Am among You as One That Serveth,” Element: A Journal of Mormon Philosophy and Theology 5, no. 2 (2009): 57–67.

[2] Dallin H. Oaks, “The Challenge to Become,” Ensign, November 2000, 32.

[3] Thomas of Celano, The Life of Saint Francis, in The Francis Trilogy, ed. Regis J. Armstrong, J. A. Wayne Hellmann, and William J. Short (Hyde Park, NY: New City Press), 58.

[4] Thomas of Celano, Life of Saint Francis 88.

[5] Bonaventure, Legenda maior, or “The Life of St. Francis,” in The Soul’s Journey into God, The Tree of Life, The Life of St. Francis, trans. Ewert Cousins (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1978), 218.

[6] Bonaventure, Legenda maior, 239.

[7] Bonaventure, Legenda maior, 245.

[8] Bonaventure, Legenda maior, 190.

[9] Bonaventure, Legenda maior, 305.

[10] An American Dictionary of the English Language (New York: Johnson Reprint, 1970), s.v. “Countenance.”

[11] Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Symbol of Our Faith,” Ensign, April 2005, 3.

[12] Oaks, “Challenge to Become,” 32.

[13] The Teachings of Harold B. Lee: Eleventh President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. Clyde J. Williams (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1996), 574.

[14] Charles Wesley, “Love Divine, All Loves Excelling,” in Hymns for the Family of God (Nashville, TN: Paragon Associates, 1976), no. 21.

[15] See, for example, Neal A. Maxwell, “Willing to Submit,” Ensign, May 1985, 70–71.

[16] Howard W. Hunter, “Exceeding Great and Precious Promises,” Ensign, November 1994, 8.