Man of Sorrows

Jennifer C. Lane, “Man of Sorrows,” in Finding Christ in the Covenant Path: Ancient Insights for Modern Life (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 145‒52.

![Our “redemption [is] . . . brought to pass through the power, and sufferings, and death of Christ, and his resurrection and ascension into heaven” (Mosiah 18:2). Jean Pucelle, The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, fol. 82v, detail, ca. 1324–28. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954.](/sites/default/files/pub_content/image/6813/Finding_Christ_Page_158_Image_0001.jpg) Our “redemption [is] . . . brought to pass through the power, and sufferings, and death of Christ, and his resurrection and ascension into heaven” (Mosiah 18:2). Jean Pucelle, The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, fol. 82v, detail, ca. 1324–28. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954.

Our “redemption [is] . . . brought to pass through the power, and sufferings, and death of Christ, and his resurrection and ascension into heaven” (Mosiah 18:2). Jean Pucelle, The Hours of Jeanne d’Evreux, Queen of France, fol. 82v, detail, ca. 1324–28. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954.

As humans, we have an interesting blind spot. Sometimes in defending the truth of one thing, we forget another element needed to make up the whole picture of what is real. We are focused, but sometimes our desire to focus closes our eyes to other dimensions of reality. I had an interesting conversation during my first year in college that illustrates this problem. I was a first-year student at Wellesley College, a women’s college in the Boston area. There were just four of us Latter-day Saints, all in that incoming class. We attended church together in Cambridge and had a small institute meeting on campus weekly.

Occasionally we ate together. I remember one meal very vividly. At this dinner, probably by appointment, the four of us met in a dining hall with two or three evangelical students. We sat at a round wooden table in high-backed wooden chairs and talked about doctrine while we ate. One topic we discussed was our different understandings of what it meant to be the children of God. The gist of the conversation, as I remember it, was their insistence that we become the children of God by being born again and our insistence that everyone is a child of God already.

As Latter-day Saints, we were excited about what we knew about the premortal world and our relationship with Heavenly Father. We were grateful for spiritual truths that our fellow students didn’t have without the Restoration. What we didn’t appreciate at the time was that what they were arguing for was true as well. It wasn’t an either/

We are beloved spirit sons and daughters of Heavenly Parents, but we also need to become the children of God by being born again. In our discussion, we Latter-day Saints latched on to what made us different and hadn’t really explored the gospel truth of their witness. Not only the Bible but also the Book of Mormon confirms our need to be born again, to take the name of Christ upon us and become his spiritual children through covenant. Having more doesn’t mean that we should dismiss what we might not understand yet. It took me additional years and deeper study of the Book of Mormon to learn for myself what those evangelical students were testifying of that evening.

As members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we sometimes pride ourselves in not using crosses or crucifixes in our church buildings. We emphasize our focus on the resurrected Christ. We are grateful for the witness of prophets and apostles in “The Living Christ” and know that he will again return to rule and reign.[1]

In the first chapter of the book of Revelation we read of Christ’s appearance to John: “Fear not; I am the first and the last: I am he that liveth, and was dead; and, behold, I am alive for evermore” (Revelation 1:17–18). Christ is alive forevermore. He lives. But it is not insignificant that he also testifies that he was dead. Maintaining our vision of the Risen Christ while keeping an awareness of his atoning, sacrificial death is critical to having a full understanding of his nature.

In medieval devotional imagery, an extraordinary image developed that allowed people to view both the living and the sacrificed Christ simultaneously. This image is known as the Man of Sorrows, or Imago pietatis. It started as an image of Christ bearing the wounds of his crucifixion, but upright, not laying down as a dead body would do. It was not part of the visual narrative sequence of the descent from the cross, the lamentation over his body, or burial. This image was a devotional image that focused on a depiction or portrait of Christ.

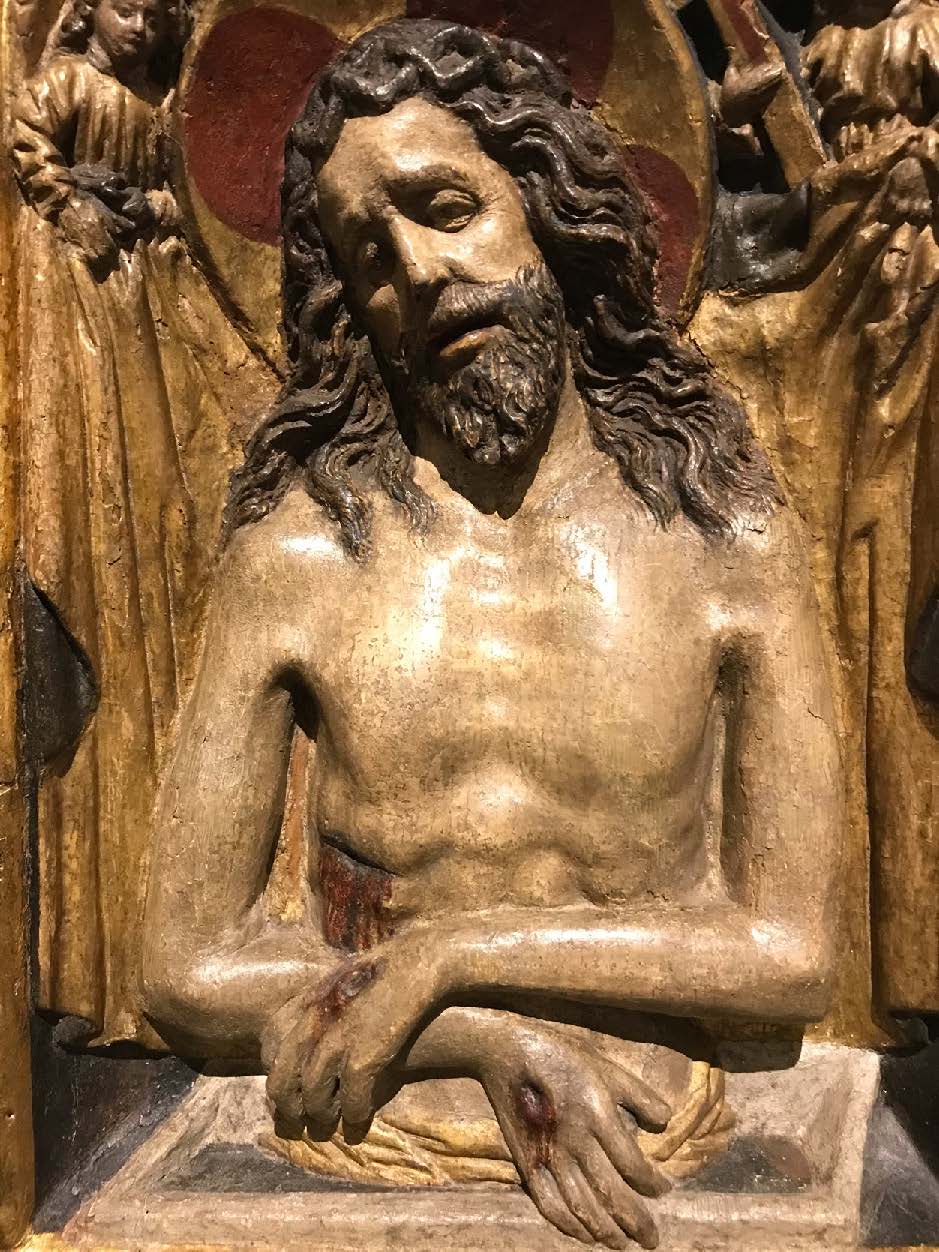

The image of the Man of Sorrows, or Imago pietatis, allowed people to view both the living and the sacrificed Christ simultaneously. Diptych depicting Our Lady of

The image of the Man of Sorrows, or Imago pietatis, allowed people to view both the living and the sacrificed Christ simultaneously. Diptych depicting Our Lady of

Sorrows and the Man of Sorrows framed by boxes for relics, detail, second half of the fifteenth century. Museum Schnütgen, Köln.

Showing Christ’s head, arms, and torso standing upright in a tomb, this portrait pointed to the Resurrection. Initially, however, the depiction was muted as his head tilted to the left side with his eyes closed, as in death. This image was borrowed in Western Europe from an Eastern Orthodox icon, but over time, it changed in its new home. Little by little, depictions in the West started to show the hands of Christ not just hanging down, crossed in front of him, but moving and pointing subtly to his side wound.

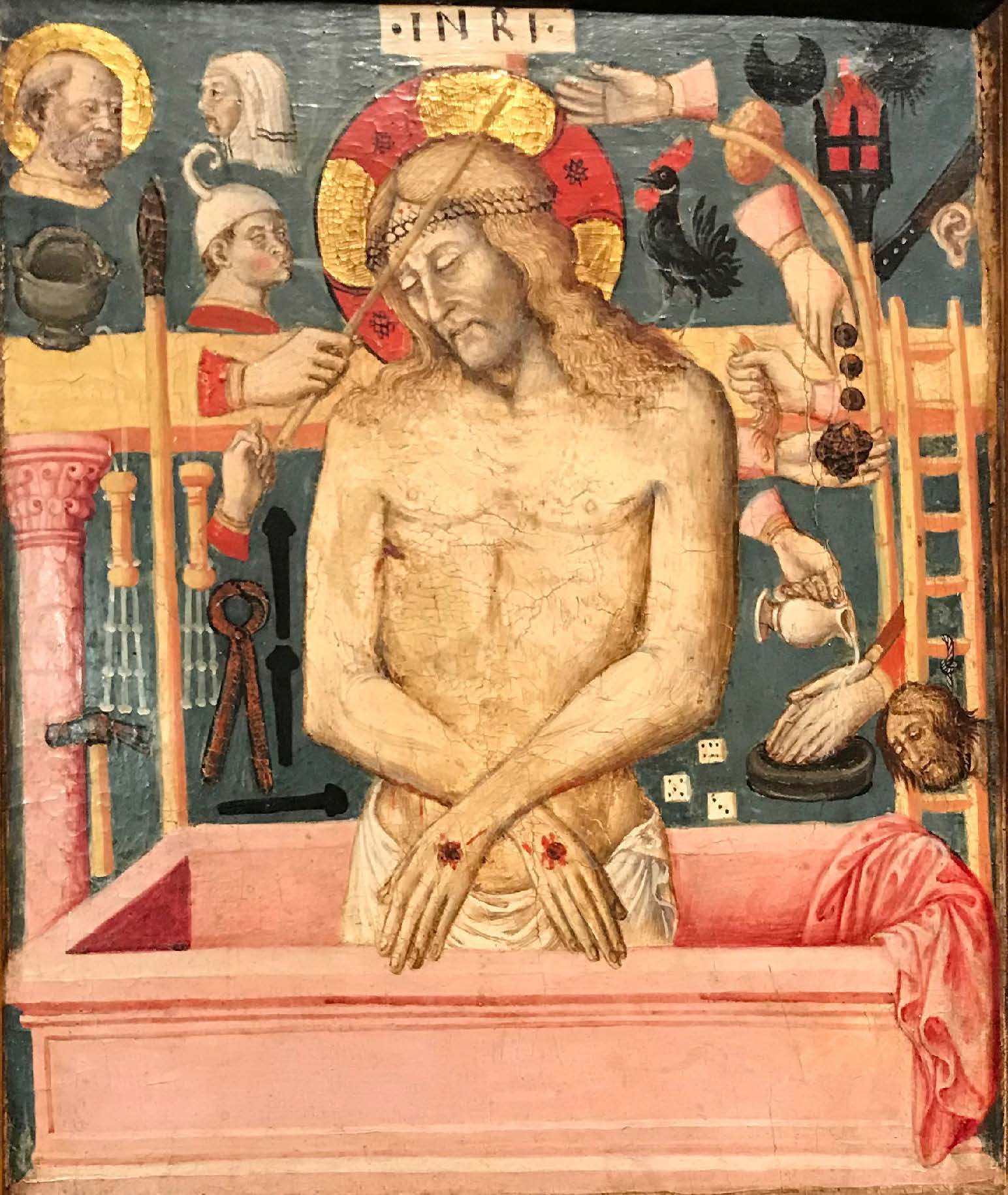

As the depictions of the Man of Sorrows changed to emphasize the living Christ, they started to show Christ with his eyes open. He increasingly looked at his audience and sometimes lifted his hands to show the wounds. With time, the depictions moved from being just the upper half of his body to depictions of his whole body, standing and bearing the marks of the crucifixion. These images usually emphasized not only the wounds, but also showed him continuing to bleed, emphasizing the immediacy of his suffering and death. Depictions of the Man of Sorrows also often showed him surrounded by the Arma Christi so that one image portrayed the entire story of his suffering, death, and resurrection.

The Man of Sorrows was not an either/

Behold the Wounds

As we think about the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world, we can also know that he is the life and the light of the world: Christ as the sacrifice and Christ as the living Word. We don’t have to pick which one to focus on because we can’t have one without the other. He is the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world, and he is the Word of God who was with God and who was God. We cannot understand who he is and what he is offering by choosing one or the other. We can’t have faith unto salvation without understanding both dimensions of his being.

The Man of Sorrows was often accompanied by the Arma Christi so that one image portrayed the entire story of his suffering, death, and resurrection. Christ as the Man of Sorrows, with the “Arma Christi,” detail, last quarter of the fifteenth century. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

The Man of Sorrows was often accompanied by the Arma Christi so that one image portrayed the entire story of his suffering, death, and resurrection. Christ as the Man of Sorrows, with the “Arma Christi,” detail, last quarter of the fifteenth century. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

In Alma 33 Alma explains the meaning of the word, which he has compared to a seed. He promises that if we plant and nurture this word with faith, diligence, patience, and long-suffering, it will grow up in us unto everlasting life. The word or message that we are to plant and nourish with our faith and diligence is “the Son of God, that he will come to redeem his people, and that he shall suffer and die to atone for their sins; and that he shall rise again from the dead, which shall bring to pass the resurrection, that all men shall stand before him, to be judged at the last and judgment day, according to their works” (Alma 33:22). Christ is the word. The message of his suffering, death, and resurrection is what we must focus on. As we seek to exercise our faith in the redemption that Christ offers, we must focus on both his suffering and death and his rising again from the dead. We can’t give one or the other priority.

Christ repeatedly presents himself to us in ways that emphasize both his life and his death. The evening of Easter Sunday, he appeared in a closed room to his frightened apostles. Seeing that they were scared and that they thought they were seeing a spirit, Christ showed his wounds as a witness of his identity: “Why are ye troubled? and why do thoughts arise in your hearts? Behold my hands and my feet, that it is I myself: handle me, and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have” (Luke 24:38–39). Not only did the wounds in his hands and feet show his identity, but they also became a source of comfort. As we behold him in his totality, we can realize that we need not be troubled or afraid. His redeeming love and his victory over death give him power, and that victory is visible through the marks in his hands and feet.

We see the exact same pattern in the Americas when Christ appeared at the temple at Bountiful. The people were afraid, and Christ’s words of comfort to them focused on the message that he bore inscribed in his own body. After “stretch[ing] forth his hand,” Christ testified of both his life and his death. “Behold, I am Jesus Christ, whom the prophets testified shall come into the world. And behold, I am the light and the life of the world; and I have drunk out of that bitter cup which the Father hath given me, and have glorified the Father in taking upon me the sins of the world, in the which I have suffered the will of the Father in all things from the beginning” (3 Nephi 11:9–11). Christ’s identity as “the light and the life of the world” cannot be separated from his suffering and death in which he “[drank] out of that bitter cup” on our behalf.

Not only does Christ teach the gathered people of the two dimensions of his nature, as the one who lives and was slain, but he also invites them to come to know for themselves. “Arise and come forth unto me, that ye may thrust your hands into my side, and also that ye may feel the prints of the nails in my hands and in my feet, that ye may know that I am the God of Israel, and the God of the whole earth, and have been slain for the sins of the world” (3 Nephi 11:14). The invitation to a personal experience was not just seeing him, but touching his side wound and the prints of the nails. This extraordinary experience was offered to each person there.

Christ’s invitation is that we come to behold and experience the simultaneous reality of his infinite life and his atoning death. We need to know for ourselves that he lives as our God and that, as God, he has given himself to be slain for the sins of the world. Only by embracing his infinite light and life combined with his suffering and atoning death can we have faith to repent and to follow his covenant path.

This is the invitation that he gives when he says: “Look unto me in every thought; doubt not, fear not. Behold the wounds which pierced my side, and also the prints of the nails in my hands and feet” (Doctrine and Covenants 6:36–37). What does it take to replace doubt and fear with hope and faith? Where can we look to have confidence that all of our wrongs, failures, and weaknesses will not be a permanent barrier to a peaceful and joyous future?

Many have suffered and died, but only the suffering and death of an infinite being can substitute for another’s sin. As Amulek testified: “nothing which is short of an infinite atonement . . . will suffice for the sins of the world” and therefore “that great and last sacrifice will be the Son of God, yea, infinite and eternal” (Alma 34:12, 14). Trusting in a vicarious, substitutionary sacrifice cannot mean looking to another human being to suffer for us. We need to know, as Abinadi did, that “God himself shall come down among the children of men, and shall redeem his people” (Mosiah 15:1). His wounds and nail marks are his witness to us that he has succeeded. They are his witness that, through him, we have succeeded if we trust and follow him.

Part of beholding his victorious wounds can come through reading and hearing the witnesses of those to whom it is “given to know,” those who are ordained as witnesses (Doctrine and Covenants 42:65). But part of knowing comes through our own personal experiences with Christ. We can feel his Spirit testify to the truth of his suffering, death, and resurrection as we ask for mercy and feel forgiveness and his redeeming love. We are also privileged to have experiences through ordinances that allow us to not only behold but also to symbolically participate in the gift of the Atonement. The ordinances point to Christ’s Atonement and help us know how to receive that power in our own life. As we will continue to explore, the ordinances connect us to Christ, and they point to a new kind of life that we can have in him. We come to know him more fully as we become more like him.

Notes

[1] “The Living Christ: The Testimony of the Apostles,” Ensign, April 2000, 2.