Arma Christi

Jennifer C. Lane, “Arma Christi,” in Finding Christ in the Covenant Path: Ancient Insights for Modern Life (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 109‒18.

Many years ago, I had an experience in which I was the target of an unexpected outburst of anger and derision. The effect on my soul and emotions was crushing. This eruption of anger directed toward me left me wounded and in pain. After enduring the tongue-lashing, I had a chance to go into a restroom to dry my tears and compose myself. There I had a sobering but uplifting experience. As I looked into the bathroom mirror, what my mind saw reflected was an image of Christ wearing a crown of thorns. I know that remembering the Savior’s suffering in our times of suffering can sometimes remind us of the message found in Doctrine and Covenants 122:8, that he has suffered more than we will ever have to go through. At that moment, however, the message that I felt was that he had felt and was feeling my pain. “Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows” (Isaiah 53:4). His sorrow helped to lift my sorrow.

In late medieval piety, sometimes the image of the suffering Christ was accompanied with the text from Lamentations: “Behold, and see if there be any sorrow like unto my sorrow” (1:12). The pervasive late medieval efforts to meditate on the suffering of Christ was not a negation of his glorious resurrection. Their belief in a bodily resurrection was a source of hope, as believers had confidence that through him they would also be raised up. Nevertheless, during mortality, through the pains and griefs that we endure, both physical and spiritual, looking to the wounds and pain of Christ can be a focus of meditation that brings comfort and healing.

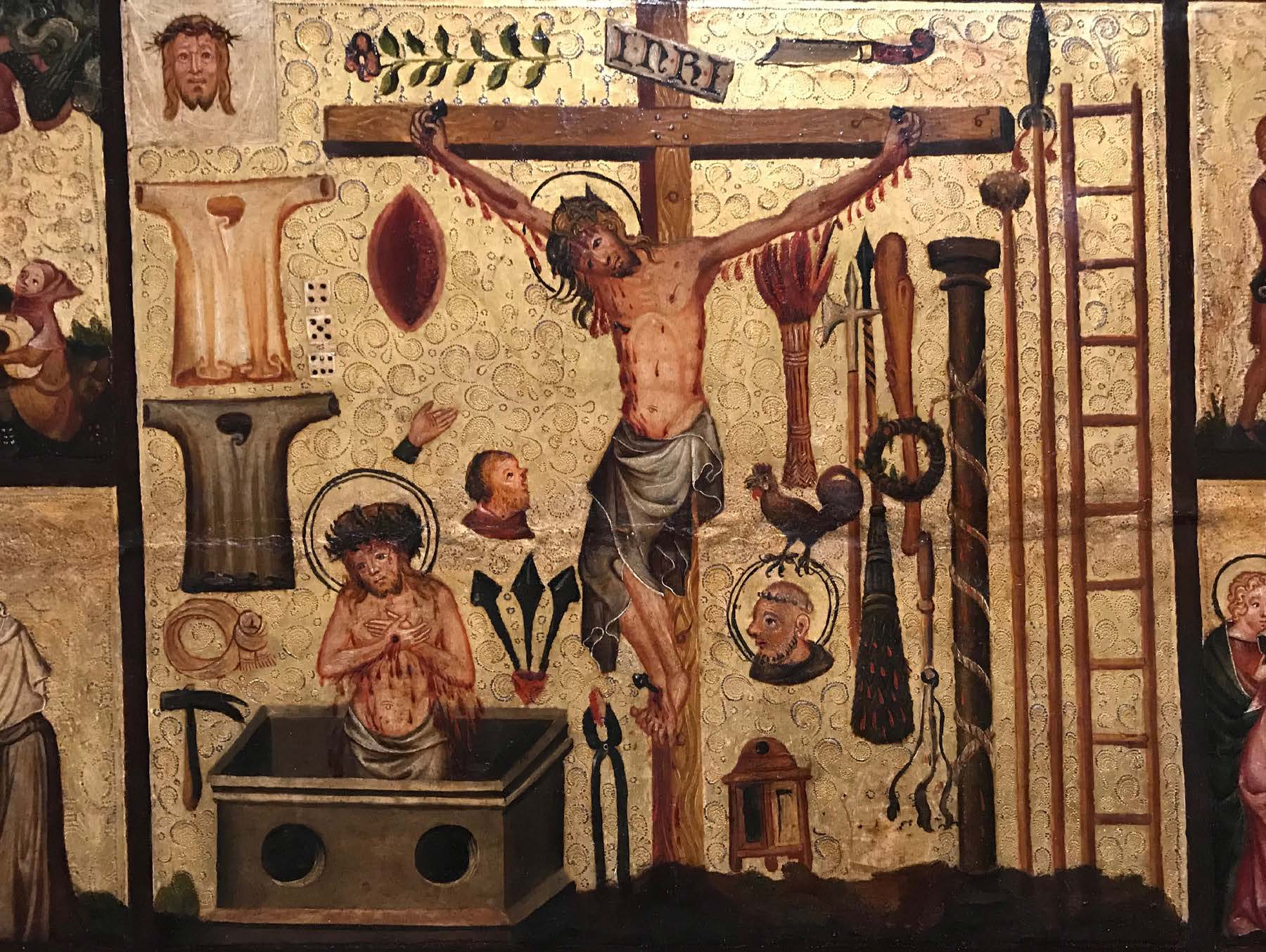

Part of the structure of this meditation in the later Middle Ages was offered through the presentation of the story of Christ’s passion, his suffering and death. A particularly focused means of meditation was often made available in visually condensed images known as the Arma Christi. With these images, one item represented one scene of the biblical passion account. Seeing a picture of a glove or gauntlet brought to mind Christ being struck on the face during his questioning at the trial. Seeing a picture of a whip or a cat o’ nine tails brought to mind Christ’s scourging. Seeing an image of the nails brought to mind his body crucified on the cross. These images, collected together to focus the mind on Christ’s suffering, were called the Arma Christi because they portrayed the arms or weapons of Christ, meaning the weapons that were used against him in his passion, but also indicating that these instruments of his suffering were his arms in the sense of heraldry and were his weapons in his victory over Satan.

In the presentation of the Arma Christi, specificity is important. These images are not a general meditation on the general suffering of Christ. The Arma Christi present specific images to aid in remembrance and meditation: the silver coins representing the price paid to betray him, the rooster or cock that crowed when Peter denied knowing him, a face that spat upon him, the crown of thorns with which he was mocked, the nails, the sponge with which he was offered vinegar, the spear that pierced his side, the ladder from which he was taken down from the cross. The Arma Christi were not, however, presented in a narrative, chronological way. They also were not detailed representations but sketches of the items. They were almost like what we would look for today in clip art representations.

The images of the Arma Christi allowed individuals to ponder Christ’s suffering and love. Scenes from Divine Plan of Salvation, detail, around 1370–80. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

The images of the Arma Christi allowed individuals to ponder Christ’s suffering and love. Scenes from Divine Plan of Salvation, detail, around 1370–80. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Köln.

This lack of detail was actually connected to the role these images played in communication.[1] The Arma Christi functioned as signs that pointed to what was real. They weren’t trying to be the object itself. In De doctrina Christiana Augustine described a sign as “a thing which causes us to think of something beyond the impression the thing itself makes upon our senses.”[2] The signifier, the reality to which each sign pointed, was a particular event of Christ’s atoning suffering and death. These signs allowed focused, particular meditation, but seen altogether, they also pointed toward the totality of Christ’s passion.

Part of the focus of the Arma Christi was on what Christ suffered; these were the weapons used against him. These images of weapons, however, also reflected Christ not just as a victim but also as a victor. Christ’s suffering and death, made possible through these physical items, were his victory over death and hell. Many images show the Risen Christ, in glory, surrounded by angels that carry the Arma Christi. He won the victory with his suffering and death. It was not a defeat but instead a glorious triumph that he gained through his willingness to suffer and die on our behalf. The Arma Christi represented, in a sense, the victory that we have through him. As Isaiah prophesied: “He was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5).

Pondering the Passion

As Latter-day Saints, we sometimes hesitate to spend time in meditation on the suffering of Christ, knowing with additional certainty the reality of the glorious Risen Lord through the revelations in the latter days. I would suggest that one way to increase our faith in his redeeming power is by taking time to consider the redemption price paid for us. In the Doctrine and Covenants, we are told to “listen to him who is the advocate with the Father” and “who is pleading your cause before him” (45:3). When we recognize how much we need mercy and when we listen to the Savior speaking as our advocate, our gratitude and love for him increase.

As we listen to our advocate, we notice what he points out to the Father. Are these things that we should behold as well? “Father, behold the sufferings and death of him who did no sin, in whom thou wast well pleased; behold the blood of thy Son which was shed, the blood of him whom thou gavest that thyself might be glorified” (Doctrine and Covenants 45:4). “Behold the sufferings and death of him who did no sin.” If Christ’s suffering and death are just an abstraction or an idea for us, it is hard for his atoning sacrifice to soften our hearts. Taking time to behold his sufferings and death opens our heart and mind to the love he had for us in order to suffer and die on our behalf. To the extent that Christ’s suffering and death remain merely a puzzle piece fitting in with all the pieces in the plan of salvation, we are not able to hear his pleading on our behalf or behold his love. Taking the time to behold the blood that he shed for us can move our hearts to a response of love and gratitude

Many of our sacrament hymns also invite us into this immediate, personal reflection on the blood shed for us. One hymn in particular evokes the same feeling that the Savior’s words do in section 45 of the Doctrine and Covenants.

Rev’rently and meekly now,

Let thy head most humbly bow

Think of me, thou ransomed one;

Think what I for thee have done.

With my blood that dripped like rain,

Sweat in agony of pain,

With my body on the tree

I have ransomed even thee.[3]

The first person language of the hymn allows us to hear the Savior’s invitation in our own voices as we sing and thus makes the Redeemer’s gift of his suffering and death personal and immediate. He did this for me. He has ransomed even me.

In Doctrine and Covenants 45, the Savior explains the reason that the Father should behold the blood of Christ: “Wherefore, Father, spare these my brethren that believe on my name, that they may come unto me and have everlasting life” (45:5). I don’t think that the Father needs persuading to spare us. The plan of redemption is his plan. He already knows the power of the redeeming blood of Christ. Instead, I think we are the ones that need persuading to believe that we can be spared. We need persuading that we can come unto him and have everlasting life.

Christ invites us to behold, to pay serious and concerted attention to his redeeming blood so that we can more fully “believe on his name” (Doctrine and Covenants 45:5). Our faith that we can “come unto [him] and have everlasting life” (45:5) will be directly connected to our ability to “behold the sufferings and death of him who did no sin.” To trust that we have been redeemed, we must “behold the blood of [God’s] Son which was shed, the blood of him whom [God gave that he] might be glorified” (45:4). God the Father gave us his Son. The Son gave us his life, his sufferings, and his death.

Slowing Down

Taking time to behold Christ’s suffering and death is not a “to do” item on a checklist of spiritual responsibilities. Beholding Christ’s suffering and death keeps the redemption alive for us. It keeps his love and ransom price real for us. I am not advocating that we plaster our walls with endless visual depictions of Christ’s passion, but I believe that we can develop habits of mind and heart as we practice slowing down to “behold the sufferings and death of him who did no sin” (Doctrine and Covenants 45:5). The individual images and symbols of the Arma Christi provide one strategy for meditation and pondering. They show us a way to behold. There is value in slowing down and separating the images of his suffering and death rather than lumping them all together under the umbrella of the Atonement. There is value in looking at the signs with an eye to understand the reality that is signified by them.

Early in the Book of Mormon, we see Nephi’s serious reflection on the future sufferings of Christ that he has learned about from the prophets. Nephi’s meditation has an additional level of soberness because he is reflecting not only on what Christ suffered but also on a universal human response to him. Isaiah 53 has a similar way of bringing us into the story of Christ’s suffering. Christ is not portrayed at a distance from us, with other people doing bad things to him. Instead, Isaiah implicates all of us in Christ’s suffering: “He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not” (Isaiah 53:3; emphasis added).

Nephi begins his meditation by considering that the way we treat the words of Christ is, in a sense, the way we treat him. “For the things which some men esteem to be of great worth, both to the body and soul, others set at naught and trample under their feet. Yea, even the very God of Israel do men trample under their feet; I say, trample under their feet but I would speak in other words—they set him at naught, and hearken not to the voice of his counsels” (1 Nephi 19:7). Nephi introduces and then moves away from the direct comparison of disregarding him and his word to trampling Christ, the God of Israel, underfoot. Still, he has introduced that image—that we can trample him under our feet with our response to him.

Nephi next focuses on how Christ was treated during his suffering and death. Note that, like Isaiah, Nephi’s emphasis is not on the historical response to Christ, but on a more general, universal human response. It is “the world” that rejects him and considers him as “a thing of naught.” “And behold he cometh, according to the words of the angel, in six hundred years from the time my father left Jerusalem. And the world, because of their iniquity, shall judge him to be a thing of naught; wherefore they scourge him, and he suffereth it; and they smite him, and he suffereth it. Yea, they spit upon him, and he suffereth it, because of his loving kindness and his long-suffering towards the children of men” (1 Nephi 19:8–9).

Nephi doesn’t focus on the historical actors, the people who lived at the time of Jesus. Instead, he depicts Christ’s submission to mistreatment as an expression of his patience and compassion toward all of us. He endures this suffering because of “his loving kindness and his long-suffering towards the children of men.” We are all implicated in what he suffers. Note that in this meditation Nephi goes through the different actions one by one: “they scourge him, and he suffereth it”; and “they smite him, and he suffereth it”; and “they spit upon him, and he suffereth it.” Each particular and specific action emphasizes the particular pain and humiliation associated with this suffering and abuse that he permitted to occur.

Emphasizing Christ’s sufferings as well as his death often leads us to focus exclusively on Gethsemane, but Nephi’s meditation expands our view to the suffering between Gethsemane and the cross. His step-by-step examination of Christ’s sufferings can be similar to the meditation on the Arma Christi. When we slow down to ponder them, we can see in each particular step of Christ’s suffering a manifestation of his love for us. Isaiah gave a similar witness of why thinking about this suffering can matter for us: “But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed” (Isaiah 53:5), or “the punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds [or welts] we are healed” (New International Version, Isaiah 53:5). As we slow down to consider the accounts of Christ’s suffering we can know more fully that he was wounded, bruised, and beaten for us. Slowing down to remember and ponder his stripes can give us additional confidence that we can be healed.

Receiving the Atonement

I received my mission call to France during the summer, but I wasn’t assigned to report to the MTC until after Thanksgiving. During that time, I worked as a waitress and spent much of my free time reading the Book of Mormon, studying French, and listening to Handel’s Messiah. I was fortunate to be able to receive my endowment several months before I began my mission, and I attended the temple every week. One of my clearest memories is actually of my first time through the temple while receiving my own endowment. There was a lot of symbolism to take in, and the part of my mind that uses words didn’t process everything. But there is another part of my mind that uses music, and as I went through the session I heard arias from the Messiah. By the time I arrived in the celestial room the one thing I knew for sure was that the endowment was about Christ and his Atonement.

Elder Bruce C. Hafen and Sister Marie K. Hafen have thoughtfully observed that in the Gospels we read the story of Christ performing the Atonement and in the endowment, we experience the story of Adam and Eve receiving the Atonement.[4] Slowing down to think about the images and signs that point toward Christ’s suffering is a powerful tool. As we read and ponder scriptures and as we attend the temple, we can see symbols and signs representing what Christ suffered for us in giving us the gift of the Atonement. Learning to ponder on these signs can help us develop capacities for meditation and reflection in considering the signs and symbols through which we receive that gift. Learning to see Christ’s suffering and death as a process can help us see that our receiving the gift of the Savior’s Atonement is also a process. It doesn’t all happen at once. There are steps and stages to the process. The gift of Christ’s ransom price can have a transformative power as we more clearly behold and receive what we are being offered.

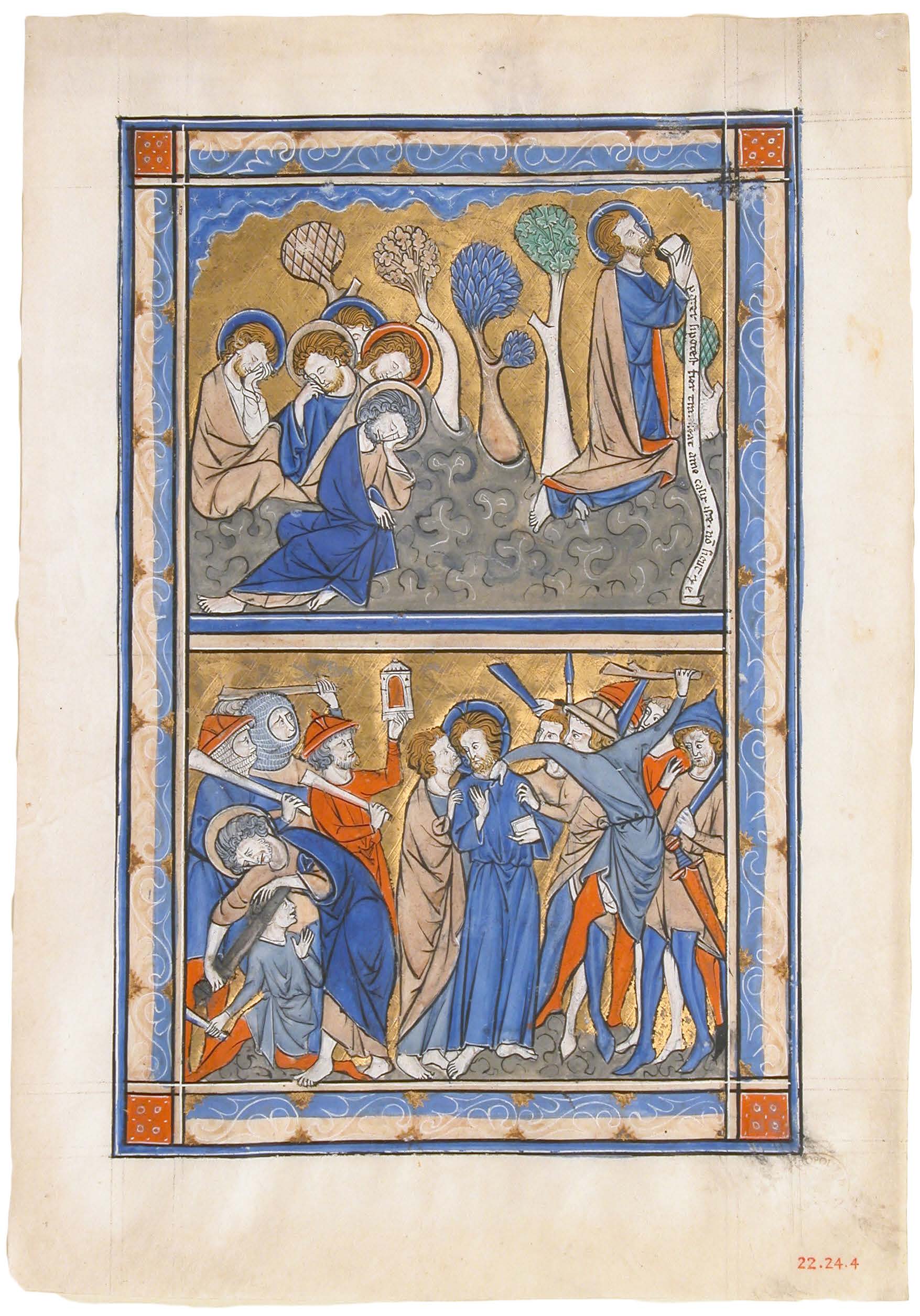

“And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground” (Luke 22:44). Manuscript Leaf with the Agony in the Garden and Betrayal of Christ, from a Royal Psalter, ca. 1270. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922.

“And being in an agony he prayed more earnestly: and his sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down to the ground” (Luke 22:44). Manuscript Leaf with the Agony in the Garden and Betrayal of Christ, from a Royal Psalter, ca. 1270. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1922.

Notes

[1] See Heather Madar, “Iconography of Sign: A Semiotic Reading of the Arma Christi,” in Revisioning: Critical Methods of Seeing Christianity in the History of Art, ed. James Romaine and Linda Stratford, Art for Faith’s Sake Series (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2013), 115–32.

[2] Augustine, On Christian Doctrine 2.1.

[3] Joseph L. Townsend, “Reverently and Meekly Now,” in Hymns (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985), no. 185.

[4] Bruce C. Hafen and Marie K. Hafen, The Contrite Spirit: How the Temple Helps Us Apply Christ’s Atonement (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015).