The Missionaries and Their Labors

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, “The Missionaries and Their Labors,” in The Field Is White, Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 57-90.

Wilford Woodruff’s mission to the Three Counties was essential in establishing and building the Church in that area. But with the preparation of the United Brethren and their desire to learn the truth, more people were interested in the gospel than he had time or energy to teach and baptize. Brigham Young and Willard Richards were the first to join him in the Three Counties. Soon, additional missionaries from America and other parts of England arrived.

As they joined the Church, several of the preachers and other members from the United Brethren were ordained to the priesthood and called to go and preach the restored gospel to their friends and neighbors—traveling, preaching, and baptizing throughout the Three Counties and across the border of Wales into Monmouthshire. Some of the leaders of the United Brethren who participated in sharing the gospel in those first few months included Thomas Kington, Daniel Browett, John Cheese, John Gailey, James Barnes, and John Spiers. Wilford Woodruff’s journal contained a baptismal record of 1840 that shows that these men baptized some of the converts on the list.[1] Elder Woodruff wrote to the Millennial Star that although many people wanted to hear the gospel, there were not enough laborers, “notwithstanding there were about fifty ordained elders and priests in this part of the vineyard.”[2]

Fortunately, several of the early missionaries to the Three Counties area wrote journals or reminiscences about their missionary service, some including the names and baptismal dates of the people they taught. As companion texts to Elder Woodruff’s journal, these other missionary writings provide the modern reader with a sense of what it was like to be a missionary at that time, how their message was received, and who was listening and responding. Some of these missionaries described their experiences in great detail, providing important insights into the process of missionary work in the mid-nineteenth century.

Barn at Moorend Farm, the home of Edward Ockey. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Barn at Moorend Farm, the home of Edward Ockey. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

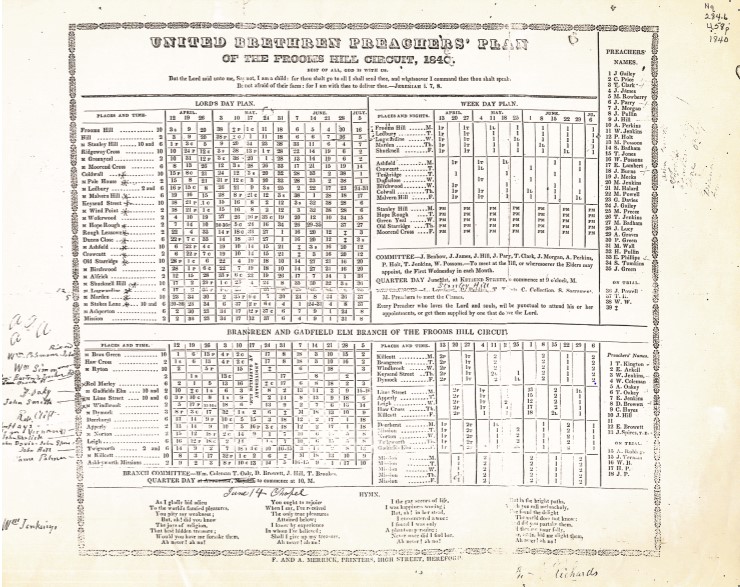

Because of the preparation of the United Brethren, missionary work in this area was successful. Along with many licensed places to preach, the group had a well-planned system for preaching at all the locations. The Church History Library holds a copy of the “United Brethren Preachers’ Plan.” The plan lists the names of forty-seven preachers along with eight others who were on trial, as well as forty-two places of worship with the dates and times of the meetings.[3] Many of the converted and baptized male preachers who had been ordained as teachers or priests may have continued to preach according to the preachers’ plan. Those ordained as priests and elders often traveled with the teachers to perform the ordinances of baptism and confirmation.

Sister Jones lived in this home, called "The Stoney," Garway Hill. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Sister Jones lived in this home, called "The Stoney," Garway Hill. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Understanding the “United Brethren Preachers’ Plan” can be somewhat difficult at first glance. Two general “branches” or groups are organized within the Three Counties region: the Froom’s Hill [sic] Branch and the Brangreen [sic] and Gadfield Elm Branch, names used later for the Church conferences created by Wilford Woodruff and Thomas Kington. The preachers’ plan listed the names of the villages or hamlets where the preaching would take place (presumably at someone’s home or barn), along with a three-month schedule for preaching. Apparently, meetings took place on Sundays at all the venues and on a weekday at a few places. The numbers listed next to each village name designated the assigned preacher, as listed on the right side of the page, so that each preacher would travel to different places to preach on Sundays and weekdays. For example, Edward Ockey lived at Moorend Cross Farm, where meetings were scheduled for 6 p.m. on Sundays and every other Friday. The preachers scheduled to teach there on Sundays during April 1840 were J. Pullin, M. Possons, and T. Jenkins. As the members and preachers of the United Brethren accepted the gospel preached by Wilford Woodruff, this elaborate schedule could still be followed but with the preachers who were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints teaching the truths of the restored gospel.

Although the names on the preachers’ plan include only first initials and surnames, the majority of those names are found in Wilford Woodruff’s baptismal record. The plan includes at least twelve women among the preachers, some who were married to other preachers (e.g., Ann and Thomas Oakey) and some who seem to have been either single or married women whose husbands were not involved in preaching. Although these women were not ordained to priesthood duties when they were baptized, they probably continued to teach their neighbors and friends about their newfound faith. They would also have been involved in the activities of the missionaries and in building up the branches of the Church.

Turkey Hall, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Turkey Hall, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Members assisted with the missionary effort in numerous ways. Many shared their homes and food with missionaries. Sarah Davis Carter remembered, “My father kept an open house for the elders. Many, many times my father and mother gave their bed to the elders, while they would take a quilt and sleep on the floor in another room, never letting the elders know they had given up their bed for them. They always made the elders feel welcome and fed them the best they had.”[4] Several missionaries’ accounts also mention how the Latter-day Saint members cared for them by providing food and shelter. For example, James Palmer noted that both Sister Morgan and Sister Jones cared for the missionaries’ temporal needs when they were in Garway.[5]

Similarly, John Spiers said that when he was very ill in September 1841 in Worcester, Sister Wright took “the greatest care of me possible to be taken, scarcely leaving me night or day” and that while praying for him, she heard a voice assuring her that Brother Spiers would not die.[6] These faithful members helped the missionaries fulfill their callings to preach the word of God throughout the area.

Groups of Missionaries

Three basic groups of missionaries preached the gospel in this area during the 1840s. The first group included the members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as well as a few other American missionaries who arrived soon after Wilford Woodruff’s first encounter with the United Brethren. The second group included recent converts from other parts of Britain who were assigned to labor in the Three Counties area. The third group was comprised of local members, many of whom had been preachers with the United Brethren.

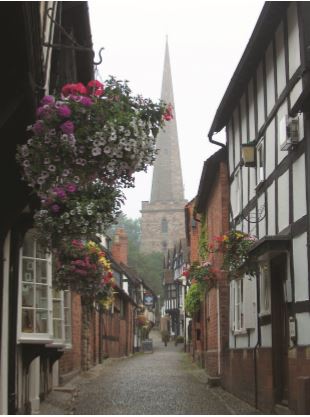

Street in Ledbury, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Street in Ledbury, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

American Missionaries. The American missionaries, including Wilford Woodruff, Brigham Young, George A. Smith, Willard Richards, and Levi Richards, have some prominence in Church history. Some of their stories have been told because they produced journals and writings about their experiences in England.[7] The American missionaries were obviously well-versed in the teachings of the restored gospel, having had extensive experience with the Prophet Joseph Smith and a relatively long period as members of the Church. Their missionary efforts are important because they were the first to preach the gospel in the Three Counties. Their enthusiasm blessed the people they taught and baptized. As British missionaries began to preach during these early years, the American Church leaders trained them for the work, helping them to gain greater doctrinal understanding and providing the authority for priesthood ordinations.[8]

Although Brigham Young and Willard Richards did not spend a great deal of time in the Three Counties area, their service was significant. In his journal, Brigham Young described his travels in the area, stating that he traveled and stayed with members in villages such as Fromes Hill (of the home of John Benbow), Eldersfield (Turkey Hall, home of Benjamin Hill), and Dymock (the home of Thomas Kington). In his travels, Brigham Young preached at various places—baptizing, confirming, holding sacrament meetings, and ordaining priesthood holders. Sometimes he traveled with Wilford Woodruff or Willard Richards from place to place, and sometimes he traveled on his own, perhaps meeting up with one of the other brethren when he arrived at his destination.[9] Although the American missionaries often met each other during their travels, their journals do not indicate whether they planned their travels together or just happened to find one another at certain meetings and stayed together for a day or two before going off to other villages.

Willard Richards wrote a letter from Ledbury, Herefordshire, dated 15 May 1840, sharing some insight into his travels and describing the way he, Wilford Woodruff, and Brigham Young were able to spread out to share the gospel with the help of some of the local members. He reported that in the previous two weeks, the three had parted, going to various places in Herefordshire, Worcestershire, and Gloucestershire, “preaching daily, talking night and day, and administering the ordinances of the gospel as directed by the Spirit.” When they met again on the day the letter was written, they compared their experiences and found that “there has been in these two weeks about 112 baptized; 200 confirmed; 2 elders, about 20 priests, and 1 teacher ordained—and the Church in these regions now numbers about 320.” He concluded by saying that there were far too many people interested in hearing the word for the leaders to meet with all of them, and that the Saints should pray for more laborers in the field to help them accomplish their work.[10]

Wilford Woodruff preached at the Ledbury Baptist Church. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Wilford Woodruff preached at the Ledbury Baptist Church. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

As described more fully in chapter 3, these three brethren of the Twelve met together on at least two important occasions toward the end of Brigham Young’s stay in the area. The first occasion was the feast day in Dymock with the converts from the United Brethren, and the second was the council they held together on top of Herefordshire Beacon where they decided to publish the Book of Mormon in England. After Brigham Young left the area, Willard Richards and Wilford Woodruff continued preaching the gospel. The two of them conducted two local Church conferences, one held on 14 June in Gadfield Elm Chapel and another on 21 June at Stanley Hill. At these meetings, the Three Counties were organized into two main conferences. The southern area was called the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm Conference, with twelve branches, and the northern region was called the Fromes Hill Conference, with twenty branches.[11] Establishing these branches was essential to the growth of the Church because on 23 June 1840, both Wilford Woodruff and Willard Richards went north for a conference to be held in Manchester, and Elder Woodruff did not return until nearly a month later.[12] By the time they left, a number of other missionaries and leaders were available for carrying on the teaching and organization of the Church. Elder Woodruff’s “Baptismal Record” ended after he left on 23 June, and he no longer listed the names of the people who were baptized in the region.[13]

George A. Smith, another member of the Quorum of the Twelve, accompanied Wilford Woodruff back to the Three Counties at the end of July and stayed in the region for nearly a month. He preached often in Ledbury, one of the larger market towns near Fromes Hill. Wilford Woodruff first preached there on 30 March 1840 when he said that "many flocked around to see me." [14] He said that the Baptist Minister allowed him to preach in his chapel,a nd afterwards, "bid [Woodruff] God speed." [15] Apparently, Ledbury was a center for Elder George A. Smith; Wilford Woodruff mentioned several times that Elder Smith had preached in Ledbury.

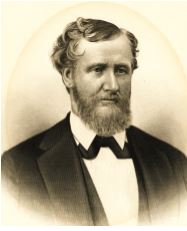

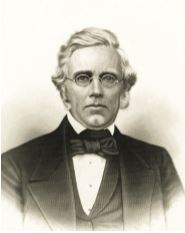

John Needham. (Church History Library.)

John Needham. (Church History Library.)

In Dymock, Elder Woodruff and Elder Smith met another member of their quorum, Heber C. Kimball, on 12 August 1840, and for a few days they joined together in preaching and meeting with the Saints in the area of Deerhurst and the Leigh, Gloucestershire. On 18 August 1840, they left the Three Counties to travel to London.[16] Elder Woodruff returned several times over the next few months before he left England entirely in April 1841. Brigham Young returned to the area in December. He attended conferences in Gadfield Elm and Stanley Hill while he was there and reported that the Church in those two conferences, along with the newly-formed Garway Conference, had 1,261 members, with a growth of 254 new members since the previous general conference in October in Manchester.[17] This growth occurred largely due to the work of the British members and missionaries, as none of the Quorum of the Twelve had been in the Three Counties since September 1840. Certainly the service of the American missionaries, including the members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, was vital as the missionary work began in the Three Counties, but other British missionaries continued moving the work forward when Wilford Woodruff and his brethren were not present.

In response to Willard Richards’s plea for more laborers in the field, additional missionaries came into the area. The minutes of the July general conference in Manchester include assignments for many local and American missionaries. For example, Elder Thomas Kington, along with William Kay and T. Richardson (both from other parts of England) joined the missionaries in Herefordshire. Brother D. Wilding went to serve in Garway, working with James Morgan, who was from that neighborhood. Brother Price was asked to give up his business and “labour under the advice of Elder Kington, as the way opens.”[18] These brethren who preached in the Three Counties represent the two types of British missionaries of this era: those who came from other counties and those who served in their local area.

British Missionaries. Among the British men from other parts of the country who were preaching the gospel in the Three Counties at the time of the October 1840 general conference were William Snailam, Joseph Knowles, John Needham, and Thomas Richardson.[19] Some of the missionary journals mentioned other British missionaries serving in the area such as Henry Glover, William Kay, and Elder Martin Littlewood. Many more may have been serving there from other parts of England, but no comprehensive list is available.

John Spiers. (Church History Library.)

John Spiers. (Church History Library.)

John Needham was a British missionary who left a detailed journal of traveling, preaching, and baptizing in the Three Counties.[20] Having grown up in Warrington, near Manchester, Needham learned of the Church when he was working in Preston as a draper. He joined the Church in 1838 and was ordained a priest soon afterward. In April 1840, he left his work and began traveling and preaching in Lancashire and Staffordshire. He did not write of how he received his assignment to go to the Three Counties, but he did describe arriving in Worcestershire sometime in November 1840 in company with some other brethren he did not name. His journal, which ends the following November, gives details of his journeys and missionary experiences in and around the Three Counties, over the border into Wales, and his travels north to attend Church conferences and to visit his family. This journal provides a wealth of information about missionary work in the British Isles in general, along with stories about experiences he had preaching, people he met, and hardships he passed through.

British Missionaries from the Three Counties. The final group of missionaries serving in the Three Counties during this period were local brethren who had joined the Church and were assigned to preach in congregations and neighborhoods in the area. Diaries or journals are available for several of these local missionaries, including James Palmer, John Spiers, James Barnes, and John Gailey.[21] Their journals, along with writings and reports from the other missionaries, indicate that many of the local brethren started teaching and baptizing others soon after their own baptism. Wilford Woodruff’s “Record of Baptisms, 1840” records the names of others besides himself who were teaching and baptizing. For example, John Cheese, one of the first to be baptized on 6 March 1840, was ordained a priest a few days later on 15 March. Elder Woodruff was gone for ten days in April to attend the general conference in Preston, and upon his return he wrote that “Priest John Cheese [had baptized] 20.”[22] The Church in this area had no lack of priesthood leadership because many of the branch leaders and missionaries serving in the region had previously been lay preachers for the United Brethren, with experience teaching and preaching.

One of the most prominent of these missionaries is Thomas Kington, the superintendent of the United Brethren when Wilford Woodruff first came into the area in March 1840. While he did not leave a journal or diary, several individuals described his involvement in the Church. On 17 March 1840, he first met Wilford Woodruff, who baptized him on 21 March and ordained him an elder on the following day.[23] Kington soon became a key figure in moving the Church forward in the Three Counties area. Elder Kington’s leadership is evident in reports of his activities, which included representing the Herefordshire Saints in the Church conferences in Lancashire, as well as providing direction to the work of the local Saints and missionaries.[24] At the first local conference in the Gadfield Elm Chapel, held on 14 June 1840, Elder Kington participated quite notably. He proposed that the branches be formed into the Bran Green[25] and Gadfield Elm Conference of the Church. Along with Wilford Woodruff, Thomas Kington also proposed and participated in priesthood ordinations. Together they made assignments for leadership in various branches in the conference. Elder Kington participated similarly in the meeting held on 21 June 1840 for the area of the Fromes Hill Conference. At each conference, Elder Kington was asked to be the presiding elder over all the churches in the area.[26] He appears to have been fully involved as a leader of both the missionaries and the members, in spite having been a baptized member for less than three months. By the July general conference held in Manchester, Wilford Woodruff reported that the combined conferences in the Three Counties had 1,007 Church members. At that time, Thomas Kington accepted the assignment to oversee the three conferences in the area: Fromes Hill, Bran Green and Gadfield Elm, and Garway.[27]

Levi Richards. (Church History Library.)

Levi Richards. (Church History Library.)

John Spiers was another of the United Brethren preachers who became a local missionary soon after his own conversion. Wilford Woodruff baptized him on 6 April 1840, Willard Richards ordained him a priest on 4 May, and he began preaching and baptizing as often as his circumstances would allow.[28] At the 14 June 1840 conference at Gadfield Elm chapel, John Spiers was called to preside over the local branch in the Leigh, Gloucestershire, where he was living with Daniel Browett’s family.[29] He fulfilled that assignment until November of the same year, while still preaching in the surrounding villages, “sometimes walking on Sundays more than twenty miles and preaching to people.”[30] His journal reported that on 25 September 1840, Thomas Kington called on him, as well as Brother Daniel Browett and Brother Jenkins, “to give up our business and devote all our time to the spread of the work.” He admitted that “this was a severe task for me, and I would gladly have done anything else, but as I had been councelled [sic] I arranged my business as fast as I could and prepared to go out.”[31]

Preparation to Preach

Missionaries for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the twenty-first century usually have at least one year of experience in the Church before their mission call. They also receive training as missionaries, first at a missionary training center and later from mission presidents, leaders, and companions. Thus, they are generally well prepared to share the gospel. In contrast, most of the missionaries of the early Church were recent converts who had minimal training and experience. Latter-day Saints of the twenty-first century may question how these early missionaries learned the gospel doctrines and practices well enough to go out to preach so soon after baptism.

Many of the early missionaries from the Three Counties had been baptized only days or weeks before they went out to preach the gospel. Many were experienced preachers for the United Brethren, but they were still young in their understanding of the restored gospel. Some training came from Wilford Woodruff and the other Apostles who taught gospel doctrines while they were in the area. Some of the local leaders and missionaries also attended the Church conferences in Manchester, where they learned more about the gospel principles. Additionally, although the members of the Quorum of the Twelve did not remain in the Three Counties, they periodically returned to meet with the Saints and to give counsel. For example, in December 1840, Brigham Young came to the Three Counties for conferences at Gadfield Elm, Garway, and Stanley Hill, where John Spiers stated that he “received much instruction.”[32]

Most of the local Saints and missionaries had not even read the Book of Mormon before going out to preach. One of the early converts, Job Smith, recollected the day when he first read from the Book of Mormon. Job was a young boy living with his uncle, George Bundy, when Willard Richards first visited their home. Job wrote, “I was reading a history of a noted Methodist preacher who had suffered some severe persecution. Brother Richards after looking at the book, asked me to put it aside for a book which he would lend me. I did so, and he lent me his Book of Mormon, turning to the Book of Ether to where the story of the voyage of Jared and his brother is written.”[33] The experience of reading from the Book of Mormon was probably rare for the new Church members and missionaries until after the first copies printed in England became available in February 1841.[34] Without the scriptures, the local British missionaries had to learn the gospel doctrines through the teachings of others, primarily from the members of the Quorum of the Twelve or more experienced missionaries from America or other parts of Britain.

The Kitchen, home of Thomas Arthur, Garway, Herefordshire. Many missionaries stayed there. The Garway Conference met here on 8 March 1841. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

The Kitchen, home of Thomas Arthur, Garway, Herefordshire. Many missionaries stayed there. The Garway Conference met here on 8 March 1841. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

One of the important methods of disseminating information to the Saints throughout Britain was the Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, a periodical that was first published in May 1840. This monthly publication was intended to “prepare all who will hearken for the Second Advent of Messiah, which is now near at hand.”[35] It included letters or reports from Church leaders and missionaries, conference reports, editorials from Parley P. Pratt and others, instruction from Church leaders, and extracts from scriptural writings and revelations. In addition, as a “harbinger of the millennium,” the Millennial Star published interesting world news that might be signs of the approach of the Savior’s Second Coming.[36]

By reading this publication, missionaries and other Latter-day Saints could learn of Church doctrines and practices, as well as other information that could increase their understanding of the gospel. When the Millennial Star began publication, Job Smith was responsible for delivering copies on foot to members, and he read it with great interest.[37] This publication communicated the Church’s beliefs to members scattered throughout the country, similar to the function of Church magazines today.

The journals of the early missionaries described the council meetings and gatherings where they learned from other missionaries and from more experienced leaders. For example, after Levi Richards came into the area in December of 1840, he began to oversee the churches and missionaries in the area.[38] James Palmer, one of the local missionaries, described Elder Richards as “an excellent man in concil [sic] sound in judgement, and endowed with a noble and generous disposition.”[39] Several times over the next few months, Levi Richards was noted in the journals as being the presiding elder for the region, presiding at conferences or meeting with the Saints and the missionaries, teaching doctrine, and providing counsel.[40]

Missionary Methods

While missionaries did not appear to have set companions, their journals mention that two of them would work together for a few days and then separate and meet other missionaries in other villages or towns. For example, as James Barnes recounted his travels from one village to another during a month in 1840, from time to time he met Elder John Cheese, Elder Clark, Elder James Hill, Elder Wilford Woodruff, and Elder John Gailey. Except for the few times when Church councils were convened, Barnes’s account does not mention whether there had been plans to meet with the other brethren; thus, many of these meetings may have happened by chance. Barnes described going to Church meetings in different villages, visiting a member’s home, or just finding the other brethren while he was walking from place to place.[41]

Little Garway Farm, the home of the Morgan Family. Wilford Woodruff stayed here and held Church meetings. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson)

Little Garway Farm, the home of the Morgan Family. Wilford Woodruff stayed here and held Church meetings. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson)

The missionary accounts tell very little about how the missionaries decided where to travel. Mention of a set schedule was usually because of a particular meeting they had previously arranged or because of a council meeting or conference. For example, soon after John Needham arrived in the Three Counties in November 1840, he wrote about traveling from place to place in the Garway area, usually staying with Church members like the Arthur family in Garway or the Morgan family in Little Garway.[42] The Arthur home was referred to as “the Kitchen” in most of the missionaries’ journals, and many missionaries mentioned staying there as they traveled through Garway. The meetings of the Garway Conference were held at the Kitchen in December 1840 and again in March 1841, with Brigham Young and Levi Richards in attendance at the first and Wilford Woodruff at the latter meeting.[43]

After the December Garway conference, John Needham went to a conference at Gadfield Elm, with Brigham Young and Elder Levi Richards, who “had lately come from America,” in attendance.[44] Although there was another conference at Stanley Hill, John returned to Garway and its environs rather than following the group to Stanley Hill.[45] He focused his missionary efforts for some time on Garway and Monmouthshire, although he did not specify whether he chose to go to that area himself or if Church leaders had assigned him to go there.

In one rather unusual example, John Spiers mentioned why he decided to go to preach in the northwestern area of Herefordshire, including Leominster and other villages. He had been teaching in the villages of Deerhurst and the Leigh, as well as the town of Cheltenham in Gloucestershire, much of the time working with Elder Henry Glover. On 29 January 1841 he recorded in his journal, “I met Br. Samuel Warren who was about starting on a mission in to the upper part of Herefordshire and he wished me to go with him. I told him I would go providing Elder Glover was willing, he therefore met Elder Glover and it was agreed to.”[46] After taking leave of the Saints in Gloucestershire, John Spiers walked with Brother Warren to Fromes Hill, attending meetings with the members there. Then they made their way north, stopping to visit with Church members such as William Jay’s family in Marden, Herefordshire.

Although it had been less than a year since Wilford Woodruff had arrived in the area, the connections of the close-knit United Brethren had spread the gospel to many villages, establishing branches and preparing missionary contacts. The members opened their homes for the traveling missionaries to hold meetings, also providing food and shelter for them. Many of these early members also invited their families and friends to hear the missionaries’ message. However, not all of the members’ families were interested or willing to hear. For example, John Spiers stated that his mother and brother did not join the Church, and they were not pleased when he accepted baptism and set out to preach.[47]

With the initial foundation for Church membership established in the areas prepared by the congregations of the United Brethren, the missionaries began to travel a little further from the three main focal points of Gadfield Elm, Fromes Hill (or Stanley Hill), and Garway. Brigham Young noted that when he came to the area for conferences in December, he stopped in Cheltenham where Elder Glover was doing good work in preaching and baptizing.[48] Although Cheltenham did not have a congregation of the United Brethren, because of its size and importance as a town it became a focal point of missionary work during the fall of 1840. Early in 1842 the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm Conference changed its name to the Cheltenham Conference. In the general conference held in Manchester on 15 May 1842, the Cheltenham Conference had 540 members with 17 branches.[49] The Cheltenham Conference membership records show that over 700 people were baptized from 1840 to 1863.[50] Today, Cheltenham is the central place of the stake in the Three Counties.

John Spiers provided insight into a missionary’s lifestyle in those early days. He described his service as he moved from Gloucestershire into northwest Herefordshire, where he opened up a new area of preaching:

This was now getting beyond the branches of the Church. During my mission in Gloucestershire I had become much discouraged at having no more success and especially so as very many people seemed to despise my testimony because of my youth and because I lacked a beard. I now felt determined to find a people who were willing to obey the truth. I therefore went before the Lord and asked Him to let me see the fruits of my labours, and also covenanted with the Lord that I would find a people willing to obey the gospel or I would die trying.[51]

In spite of Spiers’s discouragement and challenges, his covenant with the Lord to try his best to find individuals willing to obey the gospel is inspiring. He carried on teaching throughout the area for many more months, baptizing over eighty people during his mission, even while suffering with illness and persecution. For example, one evening he fainted in the middle of his speech in front of a large congregation. His companion, Brother Warren, carried on preaching until Spiers woke up again and could stand up and finish his discourse.[52] This example of determined discipleship shows these young local missionaries’ full conversion and dedication to the gospel they had embraced.

Herefordshire countryside. (photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Herefordshire countryside. (photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Missionaries today, often with the help of their families and ward members, bear a majority of the responsibility for their temporal needs while they are serving. In contrast, the missionaries of the 1840s traveled without purse or scrip (see D&C 24:18), meaning that they depended on local individuals (Church members and others) to provide shelter and food. When the missionaries ventured further from the established congregations of the United Brethren, they had to find people willing to invite them into their homes. At times they had little to eat and no place to sleep. John Spiers and Brother Warren traveled to the village of Kingsland, where they did not know anyone. They found only a hay loft where they could sleep, “but the calves kept up such a bleating as to keep us awake [a] great part of the night.”[53]

Sometimes after a meeting in a new village, one of the attendees would invite the missionaries to his or her home. Often, the individuals who invited missionaries into their homes were later baptized. For example, James Barnes related that on a Wednesday he walked eleven miles to Abinghall, where he entered the home “of Elijah Clifford tarried there and lodged there and [bore] testimony.” After staying with them several days and preaching in their home and neighborhood, on Sunday, 5 September 1840, Barnes baptized Elijah and his wife, Margaret.[54] Other missionaries had similar experiences as they ventured beyond the established branches of the Church. John Spiers recorded that as he entered the town of Leominster, “some people named Wright” fed him and then introduced him to Mrs. Tunks, who provided shelter for the night, “and from this time we had a home with these people who treated us with the greatest of kindness.”[55] Mrs. Tunks and many of her family members joined the Church over the next few months.[56]

Although Wilford Woodruff’s missionary service in the Three Counties provided the foundation, perhaps some of the real strength of the Church in this area came from those who followed him and continued to teach the gospel, helping Church membership grow. The missionaries and members were spread all over the Three Counties, not centered only in one or two locations. Branches with strong membership developed in areas such as Garway, Eywas Harold, and Orcop in southwestern Herefordshire. Other branches in Herefordshire included Leominster, Fromes Hill, Lugwardine, Stanley Hill, and Colwall. Worcestershire had branches around Gadfield Elm and Berrow, as well as the Malvern Hill areas of Alfrick and Suckley. Strong branches in Gloucestershire included Dymock, Deerhurst, Apperley, Cheltenham, and the Forest of Dean, to name just a few. Some of the missionaries also ventured into Monmouthshire, going over the mountains from Garway into Abergavenny and Llantony Abbey. Perhaps because the early Church members had friends and relatives scattered throughout the region, the gospel spread farther afield more quickly than if the missionaries had gone randomly from place to place.

Dymock Village. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Dymock Village. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

These early missionaries’ diaries show that they rarely stayed long in the same area. They may have stayed a day or two with the same family, teaching and baptizing in a particular village, but then they would move on to another town where they had made appointments to preach. They often crisscrossed each other’s paths, as one would mention going to Garway and Orcop while another would be leaving from Garway and going to Dymock or Lugwardine. They may have had certain places they would return to visit regularly, but very rarely would they stay for more than a few days. For example, James Palmer mentioned that when he passed through Orcop he stayed at the Pigeon House Estate with Mr. Daniel Price, his widowed niece who served as his housekeeper, Mrs. Elizabeth Knight, and her younger sister, Miss Mary Ann Price.[57] Later in his reminiscences, Palmer recalled that on the day he baptized Mary Ann Price, the Spirit revealed to him that “I had baptized the person that was designed by providence to become my wife.”[58] This young woman may have provided a motive for James’s many visits to the Pigeon House. He stated that Mr. Price received him very kindly but never joined the Church and that Mrs. Knight was baptized but eventually turned against the Church.[59] James Palmer married Mary Ann Price in March 1842 in Liverpool, before they embarked on the ship to travel to Nauvoo.[60]

The missionaries preached in open-air meetings or in the streets, but they also focused on finding homes, meeting places, or churches in which to deliver their message.[61] The homes and barns of the United Brethren, already licensed for preaching by the local governments, became the central meeting places for the newly formed branches and for local conferences and leadership meetings. As the missionaries moved into places with no established branches, they would seek out meeting places and arrange to preach wherever they could. For example, John Needham had planned to meet at the home of Mr. Jones in Longtown, Herefordshire, but arrived when Mr. Jones was not at home. He then found a Mrs. Davis who was willing to have the missionaries preach in her home, and a large and attentive congregation gathered. Mr. Davis gave permission for them to preach at his home another time.[62]

In contrast, John Spiers told how after he had been preaching and baptizing in Leominster, many in the town turned against the Church, and he could not obtain a house in which to preach. So he found it necessary “to resort to some stratagem to obtain one; accordingly we sent one of the members to take a house as though for private use,” and they were able to hold their meetings.[63] Two months later, John Spiers applied for and received a license for a place to preach in Leominster at a building hired by Isaac Tunks in the Corn Market Square; thus they were eventually able to establish a better meeting place.[64]

Content of the Preaching

The early missionaries had no set lesson plans or discussions to share with investigators. The journals provide a few examples of the missionaries’ methods of teaching the doctrines of the gospel. James Palmer described Elder Woodruff’s preaching. When Palmer first heard Wilford Woodruff preach, this “noble man of God” shared “gods divine law,” using the scriptures, “giving chapter and verse line, upon line here a little and there a little until we were all satisfied and our hearts ware filled with Joy [sic].”[65] Palmer testified that the Holy Ghost enlightened Wilford Woodruff as the prophets of old were inspired by the Holy Ghost to write the commandments of God. This knowledge led him and others to desire baptism.[66] Although they did not have printed materials readily available, the missionaries focused their preaching on the first principles of the gospel, the plan of salvation, the organization of the primitive church in Christ’s day, and the Second Coming of Christ.[67]

The journal of William Williams, a very dedicated preacher for the United Brethren, gives an interesting perspective about what the missionaries preached. Williams’s first experience with the Mormons came with hearing the preaching of John Cheese, a former United Brethren preacher who was a newly ordained priest in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Williams’s description of the things he heard and the change that had come over John Cheese since his baptism shows an effective contrast between the styles of preaching of the United Brethren and the missionaries for the Church. His entry is as follows:

After Singing & Prayer [John Cheese] Began Preaching in a Plain Simple Stile Concerning the doctrines of the Church of Jesus Christ Called Latterday Saints he said God had Spoke from heaven that it was our duty to repent of our Sins be baptized for the Remission of them get the gift of the Holy Ghost by the Laying on of hands Believeing in doctrine of the Resurection & eternal Judgment for God was a going to do a great work & to cut it Short in righteousness to gather the meek & Honest in Heart to Zion while Judgments Rolled thro the Nations of the earth Such in Part was the Principels upon which he discoursed he did not seem to want for any thing but Seemed to Proceed with perfect ease from first to last No excitement but a Perfect calm No Thunderings of Hell & damnation to Scar[e] us but each Part as he Proceeded he Proved from our own Bible what a change in him he seemed to teach as one having authority and we felt it and felt abashed.[68]

William Williams recognized the change that Church membership had made in John Cheese, noticing a contrast in his new preaching style as he taught about repentance, baptism, and the gift of the Holy Ghost. Even without printed materials to read, people were converted to the gospel because of the message of truth and the testimony received through the Holy Ghost. The changes apparent in John Cheese’s preaching style and the reactions of William Williams are evidence that people were convinced of truth, not merely because the preacher was exciting, but because the Holy Ghost communicated the truthfulness of the words of the preacher, who had authority from God.

Persecution

According to the pattern explained in chapter 1, experiencing joy after accepting the gospel and going out to preach in the Three Counties was followed by times of testing and trial. Although these missionaries had many successful interactions with the people as they taught and baptized in the Three Counties area, they also had their share of opposition and persecution. Sometimes the persecution was instigated by the clergy from other local churches who feared losing their parishioners. For example, in Dymock, Wilford Woodruff attributed some of the mob action to the local parish rector, saying that this religious leader stirred up the townspeople against the Saints. Elder Woodruff recorded that during one meeting in September 1840, at Thomas Kington’s house in Dymock, the local populace paraded up and down the street outside the house, beating drums, pots, and pails, trying to disrupt the meeting. They also threw stones, bricks, and rotten eggs at the home. Although the windows were shuttered, some windows and roof tiles were broken. Wilford Woodruff reports that the local brethren did not allow him to go outside for fear he would be injured by the mob, but they went out to record the names of the mob leaders so they could report them to the law. After the mob broke up, the Saints had to clear away the debris, and then they “had a good nights rest [sic].”[69]

Other missionary journals mention ministers and preachers interrupting meetings, defying doctrine, and trying to convince the listeners that the Latter-day Saints were preaching falsehoods. Despite their relative youth and inexperience in the Church, the missionaries were able to overcome those disturbances by the help and guidance of the Spirit. James Palmer wrote of a Methodist minister who got up to disturb a meeting, but after listening a little longer to the missionaries, he gave them two pence to help sustain them.[70] Not long after this incident, however, Palmer related that another minister rose up in opposition to the missionaries and demanded a sign. The missionaries replied that this heckler was part of a wicked and adulterous generation seeking for signs; afterward, the congregation left, disgusted at the way the missionaries had been treated by the minister. Palmer said the missionaries rejoiced because their sufferings for Christ’s sake would be recompensed at the last day.[71] John Spiers related a time when a minister became so combative that the congregation got into an uproar, and they called in the local constable to bring order back to the meeting.[72]

Even a local newspaper noticed that the Latter-day Saints were being treated differently than other religious groups. An article from the Hereford Times on 14 November 1840 reads as follows: “Proceedings at Dymock: ‘The Dymock Lads’ (as the male part of the population of that parish are generally called) and lasses too, have been amusing themselves very much of late by shooting, hanging, and burning effigies, which they dressed to represent some of the leaders of the ‘latter day saints’ of that neighbourhood.”[73]

Apparently, burning effigies was not a one-time or one-place occurrence for the Saints. John Spiers related that in Dilwyn, Herefordshire, the local “good Christians” influenced the rebels in the village to disturb the Latter-day Saint meeting, threatening to throw Spiers into the well and to burn the house down. Instead, they burnt him in effigy, and the next day he was accompanied out of the village by the sound of a “gang of kettles.”[74]

Some individuals followed the missionaries, taunting them or trying to frighten or injure them. John Gailey wrote that after he tried to raise a voice of warning in Ross-on-Wye, one of the villagers hit him on the shoulder with an egg, and a multitude escorted him to the edge of town, crying out against him.[75] James Palmer told of ruffians who attended a meeting and afterward followed the missionaries, throwing stones and snowballs at them, finally demanding money to let them go in peace. The missionaries gave the crowd all they had: “the enormous sum of one shilling and sixpence half penny.”[76] James Palmer noted, somewhat sarcastically, that the amount of money, which would be worth about ten dollars in the twenty-first century, was not quite the enormous sum the ruffians would have liked.

Persecution of missionaries and Church members has been seen throughout the history of the Church. These stories from the Three Counties provide representative examples of how the missionaries and members were able to overcome the challenges placed before them.

Importance of the Early Missionary Journals

Most published accounts of the early success of the Church in the Three Counties have focused on the work of Wilford Woodruff and many of the American Church leaders and missionaries in the area. However, other missionaries’ journals show that many faithful British Saints and missionaries also were important to the growth of the Church in this area. While it is impossible to know how many British missionaries served in the area in the 1840s and 1850s, due to incomplete Church records, the service they rendered in leaving their homes and going out to preach made it possible for many branches of the Church to be established.

The missionary journals provide insight into how these local individuals shared the gospel effectively, even without the resources of the present day. Most had few printed materials, but they preached the basic doctrines of the gospel with the power of the Spirit. The Book of Mormon was not easily available in Britain until after February 1841, but the Millennial Star was an important resource for teaching the doctrines of the gospel. The missionary journals relate that the early missionaries in the Three Counties often found their best converts among the friends and relatives of the members of the Church, an important reminder that Church members are the best sources for referrals to the missionaries. These journals also demonstrate that although the missionaries in mid-nineteenth-century England had many challenges, they had great faith and perseverance to carry on preaching the gospel in the face of adversity.

Notes

[1] “Wilford Woodruff’s Baptismal Record, 1840,” in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:377–95. The list contains 479 names of baptized individuals. Sometimes he wrote that others actually performed some of the baptisms.

[2] Woodruff, “Correspondence,” Millennial Star 1, no. 4 (August 1840): 82–83.

[3] “United Brethren Preachers’ Plan of the Frooms Hill Circuit, 1840,” 248.6 U58p 1840, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Although the preachers’ plan and the journals or reminiscences of others often spell the place “Frooms Hill,” the name as seen on 1851 jurisdiction maps on maps.familysearch.org and on current maps all spell the name “Fromes Hill.” Unless quoting directly from a source, we will use the correct spelling of the place.

[4] Sarah Davis Carter, “She Came in 1853,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, comp. Kate B. Carter (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1969), 12:227.

[5] James Palmer, “James Palmer Reminiscences, ca. 1884–98,” 19 (January 1841), MS 1752, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[6] John Spiers, “John Spiers Reminiscences and Journal, 1840–77,” 29 (13–14 September 1841), MS 1725, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[7] At the Church History Library, journals or reminiscences can be found for Wilford Woodruff, Willard Richards, Brigham Young, and Levi Richards discussing their missionary activities in this area.

[8] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 33 (12 November 1841). Spiers states that Levi Richards helped him organize the Leominster Branch; he ordained men to the priesthood and “gave us much useful instruction.”

[9] Brigham Young, Manuscript History of Brigham Young, 1801–1844, comp. Elden J. Watson (Salt Lake City: Smith Secretarial Service, 1968), 73–76.

[10] Willard Richards, “To the Editor of the Mil. Star, Ledbury, Herefordshire, May 15 1840,” Millennial Star 1, no. 1 (May 1840): 23.

[11] Woodruff, “Correspondence,” 83. “Minutes of the Conference Held at Gadfield Elm chapel, in Worcestershire, England, June 14th, 1840,” Millennial Star 1, no. 4 (August 1840): 84; “Minutes of the Conference Held at Stanley Hill, Castle Frome, Herefordshire, June 21st, 1840,” Millennial Star 1, no. 4 (August 1840): 86.

[12] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:470 (23 June 1840), 1:487 (22 July 1840).

[13] In his journal after this date, Wilford Woodruff sometimes mentioned baptisms, but the little notebook of baptisms has no names listed after the time he left the region on 23 June 1840.

[14] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:430 (30 March 1840).

[15] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:430 (30 March 1840).

[16] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal¸ 1:491–93 (12–18 August 1840).

[17] Brigham Young, “News from the Elders,” Millennial Star 1, no. 9 (January 1841): 239. The letter was written 30 December 1840.

[18] “Minutes of the General Conference,” Millennial Star 1, no. 3 (July 1840): 70–71.

[19] “Minutes of the General Conference,” Millennial Star 1, no. 6 (October 1840): 168. Thomas Richardson may have been the same T. Richardson who was sent to Herefordshire in July.

[20] John Needham, “John Needham Autobiography and Journal, 1840 August–1842 December,” Transcript, MS 4221, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[21] Palmer, “Reminiscences;” Spiers, “Reminiscences;” James Barnes, “James Barnes Diary, 1840 August–1841 June,” MS 1870, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; John Gailey, “John Gailey, Reminiscence and Diary, ca. 1840–41,” MS 1089, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[22] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:425 (15 March 1840) lists John Cheese’s ordination; The quote about Cheese baptizing others is on 1:440 (16 April 1840). John Cheese’s baptism is listed on 6 March 1840 in “Wilford Woodruff’s Baptismal Record, 1840,” 379.

[23] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:425–427 (17, 21, 22 March 1840).

[24] “Minutes of the General Conference,” Millennial Star 1, no. 3 (July 1840): 68–69. Page 68 shows Elder Kington submitting the minutes from the conferences held in Herefordshire, and on page 69 we see a proposal for Thomas Kington to be ordained a high priest. Wilford Woodruff, “Correspondence,” 82. In his letter to the editor, Wilford Woodruff mentions that Elder Kington had “given himself wholly to the work of the ministry.”

[25] Bran Green is spelled a variety of ways in the records, including Brangreen, Brandgreen, and Brand Green. Unless the record to which we are referring spells it differently, we will consistently spell it “Bran Green.” On a map today it is spelled Brand Green.

[26] “Minutes of the Conference Held at Gadfield Elm chapel, in Worcestershire, England, June 14th, 1840,” 85; “Minutes of the Conference Held at Stanley Hill, Castle Frome, Herefordshire, June 21st, 1840,” 87.

[27] “Minutes of the General Conference,” Millennial Star 1, no. 6 (October 1840): 165–68. The conference was held 6 July 1840 in Manchester. Wilford Woodruff reported 1,007 members from “Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, etc.,” 166. On page 168, Elder Thomas Kington received the assignment to take “charge of Herefordshire Conferences, as heretofore, also Garway, etc.”

[28] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 2.

[29] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 2–3.

[30] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 3.

[31] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 3 (25 September 1840).

[32] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 5 (21 December 1840).

[33] Job Taylor Smith, “Job Smith autobiography, circa 1902,” 3, MS 4809, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[34] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 251.

[35] Parley P. Pratt, “Prospectus of the Latter-day Saints Millennial Star,” M205.1 M646p 1840, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[36] Allen, Esplin, and Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 252.

[37] Smith, “Autobiography,” 3.

[38] Levi Richards, “Levi Richards Papers, 1837– 1867,” MS 1284, box 1, folder 1, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. In this journal, Levi Richards he arrived in Ledbury on 10 December 1840.

[39] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 14.

[40] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 29 (16 September 1841); Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 30.

[41] Barnes, “Diary,” 7–13 (September–October 1840).

[42] Needham, “Autobiography,” 21 (3–8 December 1840).

[43] Brigham Young, “News From the Elders,” 239; Barnes, “diary,” 20–21 (6 December 1840); Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:58–9 (8 March 1841).

[44] Needham, “Autobiography,” 22 (12 or 13 December 1840).

[45] Needham, “Autobiography,” 22 (17 December 1840).

[46] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 8 (29 January 1841).

[47] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 8 (1 February 1841). He actually says they “hotly opposed my going out to preach the gospel so much so that my Brother would not speak at all comfortably to me and by some it was said that he threatened my life howbeit I hardly think that to be true.”

[48] Brigham Young, “News from the Elders,” 239.

[49] “General Conference,” Millennial Star 3, no. 2 (June 1842): 29.

[50] The numbers come from the transcription of the Cheltenham Branch Records, found at the Family History Library, Microfilm #86991, items 5–8. This transcription formed part of the database described in the appendix.

[51] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 9 (8 February 1841).

[52] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 9–10 (12 February 1841).

[53] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 11 (16 February 1841).

[54] Barnes, “Diary,” 5 (possibly September 1840)

[55] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 13 (9 March 1841).

[56] John Spiers mentions the baptism of Mrs. Mary Tunks on 17 August 1841. Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 26.

[57] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 19, 21, 25, 26, to name but a few of his visits.

[58] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 50. Mary Ann Price was baptized 18 September 1841.

[59] When James Palmer went back to serve a mission in the Three Counties in 1857, he visited his sister-in-law, Elizabeth Knight, on several occasions, but said that she was not as kind to him as she had been. One example is on page 164 (1–2 March 1857) where he said he had “quite a disagreeable time with Mrs. Knight,” on account of her greediness in not giving her sister Mary Ann much of the “handsome property” from their Uncle Daniel Price’s will and testament.

[60] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 63 (14 March 1842).

[61] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 4 (26 November 1840). John Spiers said that in Kemerton, he visited many houses searching for a place to preach but was unsuccessful. On a different occasion, he mentioned that in Dilwyn, the missionaries gathered a congregation in the street, like a “Methodist Camp Meeting” in the hope that more people would be drawn to listen to them. Spiers, “reminiscences,” 20 (13 June 1841).

[62] Needham, “Autobiography,” 20–21 (30 November 1840).

[63] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 38 (3 January 1842).

[64] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 43 (25–26 March 1842). This story is corroborated by the application for a licensed place to preach, held at the Herefordshire County Record Office. It states that John Spiers applied for a license for a place to preach in Leominster at the “Corn Square” at a house “now in the holding and occupation of Isaac Tunks and others” on 26 March 1842.

[65] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 6 (April 1840).

[66] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 6 (April 1840).

[67] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 16 (27 December 1842); Spiers, “reminiscences,” 2 (3 April 1840); Barnes, “diary,” 21 (11 December 1840); Gailey, “Reminiscence,” 23 (October 1841).

[68] William Williams, “William Williams reminiscence, 1850,” 6, MS 9132, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[69] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:516–17 (16 September 1840).

[70] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 17–18 (December 1840).

[71] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 17–18 (December 1840).

[72] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 32 (9 November 1841).

[73] “Proceedings at Dymock,” Hereford Times (14 November 1840).

[74] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 39–40 (31 January–1 February 1842).

[75] Gailey, “Reminiscence,” 15–16 (July 1841).

[76] Palmer, “Reminiscences,” 21–23 (no date, but probably January 1841).