The Harvest of Converts

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, “The Harvest of Converts,” in The Field Is White, Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 91-136.

A major focus of this research was to document, insofar as possible, information about the converts to the Church in the Three Counties from the 1840s. Most previous research of the harvest of converts from the time of Wilford Woodruff’s first arrival in the area has been based on the perspective of the missionaries who went to the Three Counties. This chapter will focus on how other documents can help us understand the converts as individuals and families. In particular, we were interested in learning more about their economic and demographic backgrounds, their conversion and emigration stories, their family relationships, and the growth and development of the Church as a whole in the Three Counties over time.

To learn more about the converts, we used both personal sources, including journals and reminiscences, and public sources, particularly membership records from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, emigration records, census records, and family records found on FamilySearch.org. Several of the early converts left journals or personal histories recording their conversions and subsequent journeys through life as Latter-day Saints in the nineteenth century. We consulted written histories by individuals who emigrated to Nauvoo or to Utah whose writings have been deposited at libraries or archives in the Intermountain West. We found fewer records available for those who did not make the journey to America in the nineteenth century. We have included more information on the details of our research methods in the appendix.

This chapter and the next describe research carried out to learn more about the early converts’ individual lives and experiences as members of the Church. The first aspect of this research was to identify as many converts from the early 1840s as possible, searching to understand more about the many different reports of baptism numbers found in the writings of Wilford Woodruff and other Church leaders. Church record keeping in that time period was not complete or accurate, so the majority of the convert names used in this study come from journals and reminiscences written by missionaries and members from that area.

The second focus of this research was to learn more about the lives and experiences of these early converts, including how many emigrated or stayed behind in England. By finding the individuals in a variety of records, we learned more about who they were and if they were able to remain active in the Church throughout their lives. This chapter will focus on the converts as they first joined the Church, including their stories of conversion and their demographic circumstances. Along with trying to identify individuals and families who joined the Church, we also wanted to understand more about where the branches were located and how they were organized or disbanded. Chapter 6 will consider what happened to the converts after they joined the Church, particularly whether they remained faithful to the gospel and whether they emigrated to America to join the body of Saints or stayed behind in England.

Identifying the Early Converts in the Three Counties

Later in his life, Wilford Woodruff often mentioned the great success he had had in sharing the gospel in Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Worcestershire, including converts who had been members of the United Brethren. Depending on the circumstances of his reminiscences and the purpose of his discussion, his reflections on the success of the work did not always contain the same details. Some individuals may question the accuracy of his words, in part because he used phrases that could be seen as contradictory. For example, when he spoke about his time in the Three Counties, on one occasion he said that all but one of the six hundred United Brethren were baptized.[1] In another circumstance he talked of “1800 people” who joined the Church in the first year the gospel was preached in the Three Counties.[2] In another instance, Wilford Woodruff stated that he “baptized 600,”[3] but his “Baptismal Record 1840” shows that he baptized just over 300 people himself.[4] Further research seemed necessary to reconcile these different statements.

There are several possible explanations for the various statements regarding the baptisms and membership of the Church during the year Wilford Woodruff was in England. One obvious reason for the changes in baptism numbers is the possibility that over time Wilford Woodruff may not have remembered precise details of his experiences and thus provided a round figure in his descriptions. Simply stating that 600 people joined the Church is easier to say than a number such as 572. The number of converts from the United Brethren congregations was most likely very close to 600, because other descriptions about the United Brethren state that there were about 600 members of the group.[5]

Another possible explanation for the disparity among Wilford Woodruff’s comments about numbers of baptisms might be the precision of the words and specificity of the details that he was using at the time. He did not always state whether he was referring to the number of people he personally baptized or the number of people who were baptized in the Three Counties area. These numbers should be quite different, because soon after Wilford Woodruff performed the initial baptisms, other American and British missionaries began teaching and baptizing. If Wilford Woodruff was describing the number of people baptized in the area during the first year the gospel was preached, there could easily have been about 1,800 baptisms.

Method of Identifying Names of Converts. Because the Church in the 1840s did not keep records as carefully as in the twenty-first century, there is no feasible way to find the exact numbers of baptisms and names of those baptized in that time period. We found very few Church membership records from the Three Counties available after 160 years.[6] In the absence of a comprehensive list, we used the names found in missionary and member journals, though these sources are sporadic and incomplete. The writers did not always write the names of their converts, and there were many more missionaries and priesthood holders baptizing their friends and neighbors for whom there are no records.[7]

Many of these journals, diaries, or reminiscences are located in their original form in various record repositories in Utah; some are available in published form as autobiographies in Mormon pioneer collections.[8] In all instances, we used only firsthand accounts rather than secondary accounts, such as personal histories written by children or descendants of the original converts. While autobiographical writings can be affected by the ability of individuals to recollect their past accurately, these sources are not tainted by the embellishments of individuals of later generations who, not knowing the story from their own experience, may add to or take away from the history in order to focus the stories of their ancestors for their own purposes.

One of the most important sources for the names of converts in the Three Counties was “Wilford Woodruff’s Baptismal Record 1840,” a notebook with the subtitle “W. Woodruff’s list of the number baptized in Herefordshire England 1840.”[9] Wilford Woodruff listed the names, dates, and places for many of the baptisms in the area from 6 March through 22 June 1840, when he left the area for a conference in Manchester. After that time he no longer kept a detailed report of the baptisms, but in his journal he often mentioned individuals who were baptized or ordained to priesthood offices, noting also members he visited.[10] In addition to Wilford Woodruff, many of the converts and missionaries wrote of people they visited and baptized, which added significantly to the journal database we created. We have a name, partial name, or baptismal information in the journal database for 775 individuals. All of the baptisms in this database occurred sometime between 6 March 1840 and 5 February 1843, when the last of the missionaries for whom we had journals were no longer in the Three Counties area.[11]

After compiling the names of the converts mentioned in the journals, we searched for these individuals on other Church or public records to learn more about their movements or later involvement with the Church. Our record search included censuses in both Britain and the United States, marriage and death records, the ships’ passenger lists on the Mormon Migration website, the company records found on the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel website, and genealogies and histories found on FamilySearch.org.[12] Although the journals contained names of converts, they did not always provide other identifying information, such as gender, age, marital status, or place of residence. In many of the missionaries’ journals, we found baptismal dates and places that helped us identify the converts in public records. On rare occasions, the journal writer included familial relationships or information on age. For example, John Spiers wrote that he baptized Ann Weaver, the ninety-five-year-old mother of Mary Fox, in Dilwyn, Herefordshire. The 1841 census in Dilwyn shows Ann Weaver, ninety-five years old, living with the Thomas and Mary Fox family. Without such information, we sometimes had difficulty identifying the converts;[13] however, we did positively identify 73 percent of the 775 people on the database.

Number of Baptisms in the Early 1840s. Finding the number of converts baptized in the early 1840s in the Three Counties area can be difficult because personal and official Church membership records are scarce. However, during the first year of the Church in the Three Counties area, Wilford Woodruff recorded membership numbers in conference reports in his journal, which were later published in the Millennial Star. Unfortunately, names were not included with the numbers. The journal reports the minutes of the conferences held at Gadfield Elm on 14 September 1840 and at Stanley Hill on 20 September 1840, including the number of Church members from each of the branches of the two conferences.[14] These reports provide a total membership for the Three Counties of 1,007 in September 1840, just over six months after Wilford Woodruff first arrived in the area. When Wilford Woodruff recorded the conference meetings in March 1841, he wrote that the Gadfield Elm Conference had 408 members and the Fromes Hill Conference had 1,008 members, adding in the newly created Garway Conference with 134 members. Thus by the end of March 1841 there were at least 1,550 members in the Three Counties.[15] The reports also mention that some converts had died, emigrated, or been excommunicated by the time of the conferences, meaning that the number 1,550 does not include such individuals.

There are no complete records of how many people had emigrated from the Three Counties by March 1841, but records show at least seven ships with Mormon emigrants leaving from England between September 1840 and March 1841.[16] Several of those ships did not have complete passenger lists, so we cannot know how many individuals were on them. Although not all of the emigrants in those ships would be from the Three Counties, over fifty of the converts from our journal database were on the ships, including the Benbow, Kington, and Holmes families, who had left England before the March 1841 conferences. Possibly quite a large number of the early converts from the Three Counties had already emigrated to Nauvoo by March 1841, when Wilford Woodruff noted there were 1,550 Church members in the area.[17]

Simply stated, we may never find a definitive answer to the question of how many people joined the Church from the Three Counties during Wilford Woodruff’s service there. However, evidence supports there were between 1,500 and 2,000 converts. While there is no comprehensive list of individuals who were baptized during the preaching of the early missionaries in the area, Wilford Woodruff’s recollection of about 1,800 converts is likely to be very close to the correct number, although we may never know all of their names.

Understanding People Through Stories of Conversion

While we cannot know the stories of all 1,800 members of the Church, a number of journals and autobiographies of these early Saints help us glimpse the way the people in the Three Counties were prepared to hear and accept the message of the fullness of the gospel. Because we could not begin to tell the stories of all these converts, we focused our research on the first-person accounts we could locate.

Seekers. Many of the converts from this part of England were members of the United Brethren sect, a break-off from the Primitive Methodists. The United Brethren were searching for a purer form of Christianity than they had found in other churches. Many of those who were members of the United Brethren could be classified as “seekers,” or people who had belonged to more than one religious group because they were looking for something different than their earlier experiences with religious worship. Thus, when they heard the gospel preached by Wilford Woodruff and other missionaries, they were prepared to accept it and be baptized.

Thomas Steed and his wife. (Church History Library.)

Thomas Steed and his wife. (Church History Library.)

Thomas Steed’s family was among the seekers. Thomas was a young boy in 1835 when he and his parents joined the United Brethren and opened their home for preaching. In addition to participating in those meetings, his parents continued to send Thomas to the Church of England Sunday School at the Abbey Church in Malvern.[18] While attending Sunday School, Thomas “asked [his] teacher if anybody knew if God lived, and if Jesus was the Redeemer crucified 1800 years ago.” The teacher answered, “My boy, you ought not to ask such question, you ought to believe; I don’t know and I don’t know who could tell you!” Thomas asked the same question of other people, and he received the same answer. He stated, “That caused me to think that there was nothing in religion, if nobody knew anything about these things, and I made up my mind to have nothing to do with it.”[19] Thomas Steed’s desire to learn answers to questions of eternal worth and the inability of local religious leaders to supply these answers provided fertile ground for the seeds of the gospel when Wilford Woodruff arrived in 1840.

One of the places Elder Woodruff preached at in the summer of 1840 was the Steed family home at Pale House, in Great Malvern. Thomas wrote that prior to the meeting with Wilford Woodruff, his sister Rebecca had informed him that the Apostle had the same authority that the ancient Apostles had held. Thomas attended the meeting and later wrote that he “heard the first principles of the Gospel, a Gospel sermon preached in all simplicity and plainness, for the first time in my life. I was convinced in my mind that the principles he advanced are true.”[20] Right away his parents and five of his eight siblings were baptized. Thomas and his two younger brothers were baptized during the next few months, as were several aunts and uncles. Thomas had only one sibling—an older married sister—who did not join the Church.[21]

Fourteen-year-old convert Thomas Steed experienced a marvelous spiritual manifestation while at a gathering of Saints at the home of Jonathan Lucy in Colwall. Thomas recorded it later in his life.

Jonathan Lucy's home in Colwall, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Jonathan Lucy's home in Colwall, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

All at once a power put me on my feet, the Spirit of prophecy rested upon me. . . . The house was filled with the Spirit and the power of God, and every one present was thrilled with the convincing power of the Holy Spirit and which I could feel through my whole system like fire shut up in my bones. It was then plainly made known unto me that God lives, that Jesus is the Redeemer and that Joseph Smith was a prophet of the Most High God. Of the truth of this a doubt has never crossed my mind from that day to this.[22]

Although a young man, Thomas received the gift of tongues on that occasion, enabling him to prophesy of things to come for the group of Saints, including their eventual travel to Nauvoo along with other events to occur in England.

Another truth seeker with an early interest in eternal principles was John Gailey. His desire to find truth began as a young boy.

When I was young I was deeply concerned about eternity and the coming of the Son of God, but I told no one any thing about it for some time. After awhile some Preachers visited us calling themselves Primitive Methodists, holding forth Salvation through Christ by faith alone. I attended to their preaching for some time, and at last joined their Church. . . . Soon after I left the first and joined the united brethren as a local preacher that was to preach on Sundays which I continued to do one year and ten months. Thomas Kington who was then our leader, desired me to give myself wholy to the ministry which I did. This was in 1836. . . . I continued to preach amongst them till in 1840 when it pleased God to send Elder Wilford Woodruff to Castle Frome with the fulness of the gospel.[23]

Similarly, John Spiers’s early views on religion led him to become a seeker, join the United Brethren when he was young, and become involved in teaching and preaching. The coming of Wilford Woodruff changed John, along with the entire group of United Brethren. John said:

When quite young I had very serious thoughts of religion and was zealously attached to the Church of England. When I was about 15 years I began to view the abominations of the Church of England (more particular the character of her ministers than her doctrine) and shortly attached myself to a body of Methodists who had seperated from the Primitive Methodists under a Mr. Thos. Kington, and others and taken the name of United Brethren. I was appointed class leader of the Redmarley class . . . and before I was 17 years old was appointed a local preacher which appointment I at first refused but afterwards accepted.

Early in the year 1840, Elder Wilford Woodruff of the twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints came from America, and shortly came into Herefordshire and introduced the principles to some of the leading men of our society who fell in with them and was baptized. Mr. Kington after much debate with him, embraced the work and then introduced elder Woodruff all through his society most of which embraced it and those who would not were scattered so that the society was broken up, on the 3rd of April (1840).[24]

Malvern Hills. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Malvern Hills. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Dreams. Spiritual preparation takes many forms. Some individuals were prepared for the gospel or guided onto a path toward it through dreams. John Needham related a dream that he heard from a Sister Smith, a former member of the United Brethren living in Herefordshire who had joined the Church before Needham arrived on his mission to the area in November 1840.[25] Sister Smith told him that in February 1837, before the first missionaries arrived in England, she had a dream in which she saw a high hill, and on the summit was a beautiful building that looked like a church with a narrow white path leading to it. The whole scene was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen, and she felt a great desire to climb the hill. However, she was told that to ascend the hill she must first go down to the garden where she would learn what to do. She entered the garden and found five men standing in a circle, each holding an open Bible. She was told that these men would tell her what to do. They said they were sent from Jesus Christ to “put everyone in the way” before individuals could ascend the hill.[26] While she visited with them, they all sang a hymn, “The Spirit of God like a fire is burning.”[27] They then prayed in a way she had never before experienced, bringing to her a feeling of happiness beyond anything she had so far felt in her life. After she awoke, she often wondered about the meaning of the dream. In March 1840, when she met Wilford Woodruff in Herefordshire, she recognized him as one of the men in her dream. When she attended a meeting a week or so later, she heard him sing “The Spirit of God Like a Fire is Burning.” Later, when she met Elder Brigham Young and Elder Willard Richards, she recognized them as being two of the other men she had seen in the garden in her dream.[28]

A dream his mother received led William Williams to join the United Brethren, resulting in opportunities for William, his family, and work associates to hear the restored gospel. William described how his family attended the Church of England because his mother taught Sunday School classes, but at times they would go to hear other preaching because they were not satisfied with the Church of England’s teachings. He related that his mother had a dream that he (William) could get a shoemaking apprenticeship with a Samuel Jones in Malvern Hills.

She went immediately [to see Mr. Jones]. This I Pressed her to do She Loved me to well not to go she went that day I was engaged to go on the next monday I mearly mention this that whoever Reads may See the hand of the Lord in it. . . . My Boss was a Preacher amongst the United Brethren they Believed nearly the Same as the Methodists he Pressed me hard to go and hear them I went I thought them a People that were Sincere in their devotions I soon found that Spirit was catching I knew not what to do I went amongst others I had lost all relish for the Church of England and my Prayer was Lord lead me in the right way. . . . My Master urged me to attend their Prayer meetings I went one night with him.[29]

William felt that the United Brethren “tried to love truth and embrace it whereever found,” so he began attending their meetings. He recounted how John Benbow, a member of the group, told them “of some strange men that had come from America who preached without money & had made considerable Stir in the Potteries Manchester &c all these things seemed to be subjects of thought and talk.”[30]

William Williams was not convinced of the truth of Elder Woodruff’s teachings upon first hearing them. He described that some of his fellow preachers of the United Brethren, including his boss, Samuel Jones, were concerned about the effect this American was having upon their associates. Samuel Jones organized five of the preachers to fulfill preaching tasks that some of their newly converted Latter-day Saint preachers had given up. He was fighting against this new doctrine and resisting “all encroachments on our liberty by Strangers.”[31] This they did for nine weeks, and William confessed that although they had opposed these men and their new religion, they all secretly wished to hear them. William went to his preaching appointment one Sunday, and he found that John Cheese, a former very zealous member of the United Brethren who had become a Latter-day Saint, was also there. William slunk to the back of the room, refusing Cheese’s invitation to preach. As described in chapter 4, Williams found that Brother Cheese proceeded to preach the restored gospel with authority and in a plain style so unlike his previous teaching manner that Williams was left feeling abashed, puzzled, confused, and distressed.[32]

On the following day, while at work with fellow United Brethren preachers, William told them of his defeat at preaching. His colleagues told him to try again the following Sunday. They told William that if he were crossed again, he should take Cheese to Colwall, where the boss (Samuel Jones) would “fight them himself and we could listen.”[33] On the following Sunday, John Cheese was there again to spend the whole day with William at his preaching appointment. Cheese preached and baptized several of their best members, and so William pressed him to go to Colwall on Monday evening. William returned home, not in triumph, but in hope that his fellow brethren would feel as he had. Cheese preached the following evening, and five people, including William, were baptized. Soon after this experience, Williams reported that Wilford Woodruff came to visit his boss, and Samuel confessed that he believed the gospel and desired baptism.[34]

Impressions. Mary Ann Weston’s experience shows the effect Wilford Woodruff’s presence and inherent goodness had on some of the young converts. Mary Ann was an apprentice dressmaker living with a young couple, William and Eliza Phelps Jenkins, in The Leigh, Gloucestershire. Wilford Woodruff had baptized William Jenkins while Jenkins was visiting friends in Herefordshire. Soon after arriving home, Jenkins told his wife and Mary Ann about his experience and baptism. Mary Ann recounted that she was the only one at home when Wilford Woodruff first visited the Jenkinses’ home. She was greatly affected by Woodruff’s demeanor as he sat by the fire and started to sing a hymn. She recalled that “while he was singing I looked at him. He looked so peaceful and happy, I thought he must be a good man, and the Gospel he preached must be true.”[35] She was soon baptized by Elder Woodruff in the pond in the middle of the village at midnight for fear of persecution.

Charles Sansom, like many early converts to the Church, was quickly impressed by the feelings he had when he encountered the missionaries and the gospel. He recalled his first connection with Latter-day Saint beliefs:

In the fall of the year 1844 I became acquainted with a young woman of the Mormon faith, Pamela Knight. I went with her to hear the Mormons preach. I was soon convinced of the truths of the doctrine they taught. I received the glad news with a joyful heart. At New Year’s holiday I went home to visit my mother and soon found that Mormonism had found its way there since I left. During my stay I was baptized at Avening, January 3, 1845, and confirmed at Chalford by Brother Webb.[36]

Charles’s mother did not join the Church, but he did not lose his enthusiasm. “It was truly a happy time for me to realize that I was living at a time when the true gospel was again on the earth; when apostles and prophets and the gifts of the gospel had been restored. I used to wish I had lived in the days of the Savior and his apostles.”[37]

Learning the Gospel Through Family Relationships

While identifying the converts in the journal database, we found that a number of them shared family ties.[38] Because many of the converts in the Three Counties were already closely connected through their membership in the United Brethren, the doctrine spread easily among them, and they joined the Church together. Many were also related through blood or marriage ties.

Site of William and Elizabeth Collett's home in Frogmarsh, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. The Thomas Oakey family lived with William according to the 1841 census. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Site of William and Elizabeth Collett's home in Frogmarsh, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. The Thomas Oakey family lived with William according to the 1841 census. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The conversions of the Benbow family demonstrate the strength of such ties. Wilford Woodruff would not have gone to Herefordshire if William Benbow, who had been baptized in Staffordshire, had not invited Elder Woodruff to visit his brother John Benbow in Herefordshire. John and Jane Holmes Benbow were the first to hear Wilford Woodruff preach in the Three Counties, and they offered their home and the pond on their property for preaching and baptizing. The Benbow family and several of their family connections were baptized: twelve individuals with the last name Benbow are listed in Wilford Woodruff's baptismal record. FamilySearch Family Tree and other records show that these individuals included John Benbow’s mother and several of his siblings and their spouses, along with some nephews and nieces. Not all of the Benbow relations carried that surname. Woodruff’s baptismal record also includes Jane Holmes Benbow’s nephew Robert and his wife, Elizabeth Cole Holmes, who were baptized on 9 March 1840.

Wilford Woodruff’s record also lists several of the Holmes relatives and connections. Not only did Robert and Elizabeth Holmes have immediate family members and cousins who joined the Church, but some of the spouses’ families were also baptized. Elizabeth Cole Holmes’s father, William Cole, was baptized on 1 June by Wilford Woodruff. Francis Holmes, another of Jane Benbow’s nephews, was married to Hannah Gittens, whose mother and siblings were baptized by John Gailey in 1840.

Another family group of new converts was the Thomas and Ann Collett Oakey family and their relatives. Both Thomas and Ann Oakey were listed on the “United Brethren Preachers’ Plan” as preachers for the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm Branch.[39] Ann’s parents (William and Elizabeth Bromage Collett), her brother Daniel Collett, and her sister Elizabeth Collett Ruck were all baptized by Wilford Woodruff or by Thomas Oakey. Brother Oakey also had many family members who joined the Church, including a sister, Esther Oakey Harris, and several cousins: Robert Harris, Dianna Harris Bloxham, and Elizabeth Harris Browett. Robert Harris’s wife, Hannah Maria Eagles, had several siblings who joined the Church. Her mother, Ann Sparks Eagles, had married Samuel Roberts after her first husband died; many of the Roberts children and their families were also baptized.

Home in Brand Green. (Bran Green in now called Brand Green.) (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Home in Brand Green. (Bran Green in now called Brand Green.) (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

As the Benbows, Holmes, Oakeys, and others heard the gospel and joined the Church, they invited their family members and connections to learn more about their newfound faith.[40] Thus we found that the early converts to the Church were connected not only by their religious faith but also by ties of family and friendship. The converts generally were not individuals who just happened to be in the neighborhood to hear Wilford Woodruff preach. Certainly, when the gospel was first preached in the area, the United Brethren congregations had a significant role in bringing people together. In addition to their previous religious affiliation, the converts were also family members, neighbors, and friends. The gospel net spread out quickly to their kindred and connections.

Exploring the Demographic Background of the Early Converts

One of the purposes of our research was to learn as much as possible about the people and the growth of the Church in the Three Counties in the first twenty years after Wilford Woodruff came into the area. We wanted to learn more about the type of people who were joining the Church in that area in the mid-1800s, including their occupations, social status, gender, and age. Past researchers who have examined the socioeconomic status of the early Church members in England have found that typical British converts were urban and of the lower social classes.[41] In fact, a study of the Mormon emigrants who left England during the years 1850–62 stated that the overwhelming majority came from towns, with nearly 90 percent of them having occupations associated with the lower classes.[42] Similarly, one of the early United Brethren converts, Job Smith, described the United Brethren as including a “great many very poor people as its members, and few working men in fairly good circumstances, and one man who might be called wealthy, he being a farmer and owner of some land.”[43] Information in the database enabled us to go beyond mere anecdotal data and reminiscences to examine more specific information regarding the socioeconomic conditions of the converts in these counties.

Home in Frogsmarsh. (Frogmarsh in now called Frogsmarsh.) (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Home in Frogsmarsh. (Frogmarsh in now called Frogsmarsh.) (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

To add to the information from the journal database, we examined Church membership records from the Bran Green and Frogmarsh branches to learn more about Church growth after the initial missionaries left in the 1840s. Although the membership records for the local branches in the Three Counties are not complete, we chose to do a case study of the membership records from the Bran Green Branch and Frogmarsh Branch, some of the first branches organized in 1840 for which actual records are still in existence.[44] These branches encompassed the area in and around the Gadfield Elm Chapel. [45]

Our database for these branches was much smaller than the journal database because we used only the records from the Frogmarsh and Bran Green Branches. Although they may have originally been separate branches, the records appear to have been blended. We found them collected together on microfilm, with many duplicates on the pages of both branch records. After deleting the duplicate names, we identified 118 unique individuals listed in the membership records between 1840 and 1856.[46] Later references to the “branch database” refer to both the Bran Green and Frogmarsh Branches. Because some of the membership records included information about parents’ names, birth years, and birth places, we could positively identify 86 percent of the database names in the other record sources.

View from Brand Green north to Pauntley Court. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

View from Brand Green north to Pauntley Court. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Occupations and Social Status. During the time of Wilford Woodruff’s mission, the Three Counties were largely agricultural, as they are today. Although several large cities were nearby, including Cheltenham, Bristol, Worcester, Hereford, and Gloucester, Elder Woodruff rarely mentioned going to them. He spent his time teaching and preaching in the villages. Many of the early converts would likely have been agricultural laborers. When Wilford Woodruff described the converts in the Three Counties, he noted that there were people from “most all classes & churches, 46 Preachers one clark [sic] of the Church of England, one constable & a number of wealthy farmers.”[47] According to this statement, there was a wide spread in the economic and social status among the early members of the Church, ranging from poor laborers to wealthy farmers.

Accounts by Job Smith and other journal authors noted that a number of converts struggled financially. For example, John Spiers’s father had died when John was about six years old, and John’s mother provided for the family as a dressmaker. As John’s elder brother grew older, he became an apprentice to a tailor and was able to help with the family finances. Their mother gave them all the education she could, which consisted of reading, writing, and some arithmetic. John worked for masons and bricklayers when he was old enough to be employed.[48]

Living in Bristol, Frederick Weight described the difficult circumstances of having an unemployed father in nineteenth-century England:

When I was about sixteen or eighteen years of age, my father was out of work a good deal and as it happened I was in work most all the time and poor people in England know very well what it means to be out of work. It means to be out of everything, house and home. I was getting thirteen shillings per week at this time and this enabled us to just keep the wolf from the door. I gave my mother my wages every week. She could just pay the rent and buy us bread from week to week and a little bacon and a peck of potatoes each day. This was all we had to live upon from week to week for about eight of us. My wages just kept us from running debt and from starving.[49]

While the parish clerk and the constable that Wilford Woodruff mentioned are not identified in database sources, we do know that two of the wealthy farmers were John Benbow and Edward Ockey. As a tenant farmer, John Benbow had a lifelong lease on his farm. After his baptism, the landowner apparently made life difficult enough for him that he chose to leave his home and farm.[50] John Benbow used his wealth to help others. For example, he and Thomas Kington were able to provide significant money to help with the publication of both the Book of Mormon and a Church hymnbook. When he emigrated to Nauvoo in September 1840, John Benbow paid for the passage of forty of the other Latter-day Saints.[51] When Edward Ockey emigrated to Nauvoo, the advertisement for the sale of his possessions at Moorend Farm shows that he had been prosperous.[52]

View of Hill Farm, home of John Benbow. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

View of Hill Farm, home of John Benbow. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Autobiographies and journals of missionaries and early converts provide stories of a number of other converts from the Three Counties who were also financially well off. Some of them were merchants or skilled artisans or laborers; others were individuals born into wealthy families. Not all the new Church members were just eking out a living as unskilled laborers, as is sometimes reported.

For example, Mary Ann Weston Maughan’s father was financially stable as a merchant owning a shop on the High Street in Cheltenham, along with other properties in nearby villages. The family lived in Corse Lawn, near Eldersfield, Worcestershire, and employed servants. Mary Ann described her grandmother’s relatives as part of the high gentry, meaning that they did not have to work for a living.[53] Similarly, Emily Hodgetts Lowder’s father owned a great deal of land, and she was educated in a private school. Her father retired from business when she was very young, and she remembered many pleasant trips with him. Emily had her own pony to ride back and forth to the school she attended. The family was wealthy enough to have its own cook.[54]

Anecdotal data are helpful in showing the various socioeconomic levels among the converts in the Three Counties, but only a few examples are available. By looking at the occupations of the converts in our databases, we were able to see a more accurate picture of the group as a whole. This examination helped us find out whether this group of converts was made up primarily of poor people, as described by Job Smith, or by people from all classes, as noted by Wilford Woodruff.

Moorend Farm, home of Edward Ockey. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Moorend Farm, home of Edward Ockey. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The information for occupations in the databases came from the 1841 census for those living in the Three Counties on the date of the census, or from the Mormon Migration Index for those who left the area at an earlier date.[55] Although later censuses also listed occupations, so many changes might have occurred in that ten-year time period that we were not confident that later censuses reported the occupations of the converts at the time they were baptized. In addition, when the converts emigrated to Nauvoo or to Utah, the United States censuses often listed different occupations from those occupations the individuals had in England, because life on the frontier was not the same as life in a well-established society. These changes in occupation might also have shown that many people were able to change their status upon emigrating to a country where they were likely to own land and have more control over their situation.

In mid-nineteenth-century England, social status was determined by type of work, not necessarily by earnings or financial situation. For example, a poorly paid teacher or a clerk would be a social superior to a more highly paid shoemaker or carpenter, who performed manual labor.[56] The website A Vision of Britain Through Time analyzed England’s censuses using three categories or classes for occupations of working-age males to create an atlas of occupations in each county over time.[57] The first category, the middle-class group, included professionals and managers, along with farmers in rural counties. The second category was a mixed group of clerical workers and artisans or skilled laborers such as shoemakers, blacksmiths, and carpenters. The third category was composed of the semiskilled or unskilled working-class laborers, including domestic servants or farm laborers. We used similar categories in analyzing occupations in our databases. The appendix includes a more detailed analysis of the occupations our databases include.

Corse Lawn Hotel, dating from the 1700s. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Corse Lawn Hotel, dating from the 1700s. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Like Wilford Woodruff, we found a variety of occupations among the converts in our databases. In the middle-class category, we found several farmers, shopkeepers, school mistresses, and an innkeeper—although some were probably not as wealthy as others. We also found a number of people in the mixed-class group of skilled laborers or artisans, including shoemakers, carpenters, stone or brick masons, miners, blacksmiths, tailors, dressmakers, milliners, or glove makers. Among the unskilled laborers, agricultural laborers made up the largest percentage of converts, as expected, along with servants and laundresses—most of whom were women. In the journal database, we found that 13 percent of the families would have been considered part of the middle class; 29 percent of those families were skilled laborers. The unskilled workers and their families composed 58 percent of the database. In contrast, the branch database showed only one farmer, with 71 percent of the members of the branch as agricultural laborers or servants. The skilled laborers in the branch database were involved in occupations similar to those found in the journal database, including carpenter, shoemaker, baker, miner, and saddler. One unique occupation in the branch database was a midwife.

Consistent with earlier research, these databases showed that the majority of the early Saints in these counties were working-class laborers. However, they were not the poorest of the poor; most of them appeared to have work of some kind. On the 1841 census, none of the converts were listed as a “pauper,” or one receiving help from the parish or government. While they may not have been rich, these Saints were able to manage to survive in spite of hardships. In fact, nearly half of the people in the journal database were working as artisans, skilled laborers, or even in what might be considered middle-class occupations. These results may be due in part to the rural nature of the Three Counties and to the fact that the early missionaries appeared to focus their efforts in the smaller villages and hamlets where many of the congregations of United Brethren were already established. According to the 1841 census, fewer than twenty-five individuals in the journal database were living in the towns of Ledbury, Leominster, and Great Malvern, and no one in the database lived in the larger towns of Hereford, Worcester, Cheltenham, or Gloucester.[58]

Gender Ratio. Gender was determined by looking at the first names or descriptions such as “brother” or “sister” used in the journals or membership records, since the journal writers very rarely specified whether a person was a man or a woman. Most of the first names in the databases were very traditional ones, such as Jane, Mary, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Charles, John, or William, so we assumed the gender of these individuals based on their names. There were five individuals for whom we could not determine gender because the first names were (1) not provided, (2) not legible, or (3) happened to be Francis or Frances. While most people might assume Francis referred to a male and Frances to a female, we could not make that assumption, in part because spelling was not standardized. In one instance, Wilford Woodruff wrote that Francis Brush was baptized in Shucknall Hill, presumably a male. However, we found the only Frances Brush living in Shucknall Hill in 1841, and she was recorded in the census as a seventy-year-old female. We found that 57 percent of the converts listed in the journal database were women, while 43 percent were men. The branch records database showed more gender imbalance, with 62 percent women and 38 percent men.

View from Shucknall Hill. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

View from Shucknall Hill. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Age. Previous research about the early Saints in England has stated that the majority of converts in Britain during the nineteenth century were in their twenties and thirties, because that age group would be most likely to have the freedom to accept a new religion and to be able to emigrate.[59] Older people would presumably have more established careers or families and would be less likely to uproot their families by changing religious affiliation and emigrating to America. We looked at the birth years for the individuals in the journal database using the census or FamilySearch.org as the source.[60] Over five hundred of the converts in the journal database were baptized in 1840, with the latest baptismal dates in 1843. The ages at baptism ranged from eight to ninety-five years old. We found that 35 percent of the converts were age forty or older at baptism, and 17 percent were under age twenty. Many of those younger than twenty were probably children of the older converts, as frequently a whole family was baptized. However, a number of the teenagers were baptized without their parents. Hence, those who would be in their twenties and thirties at baptism consisted of less than half of the people in the database.

The branch records database was a little more difficult to analyze because of the nature of the records, which included baptismal records, excommunication dates, and baby-blessing records. Eleven people were identified in the database with no baptismal date. Using the names of people for whom we had birth years and baptismal dates, we calculated the age at baptism for ninety-five individuals. We found that only 32 percent of the converts were in their twenties or thirties at the time of their baptism. As in the journal database, a number of families were listed, so we found that 25 percent of the converts were children and teenagers when they were baptized, and 43 percent of them were forty or older. The oldest person in the branch records was eighty-two at the time of baptism.

Unlike the findings of earlier studies, we calculated that the majority of the early converts from the Three Counties were not in their twenties and thirties. Although these findings are slightly different from demographics of converts in other parts of the British Isles, they may be explained by the particular characteristics of the United Brethren. Many of the United Brethren had been meeting together for several years prior to being introduced to the teachings of Wilford Woodruff. Some perhaps had joined the United Brethren in their twenties and thirties, ages at which they were more open or enthusiastic toward changing their religious affiliation. As they had continued meeting together and forming strong bonds of fellowship, making the change to another new religion with their friends and family did not cause as much disruption to their lives as it would for older people who had never changed religions. Another age-relevant characteristic of this convert group was that many families were baptized in which the parents were older and the children younger than the average convert in other parts of England.

Recognizing Blessings and Opposition

Life was not always easy for the new converts of the Church in the Three Counties. They had their share of tribulation, but they also received many blessings because of their newfound faith. For example, some of the young adults who joined the Church who had not yet married were able to find partners among other converts. As described in chapter 4, James Palmer met his future wife, Mary Ann Price, because her uncle allowed the missionaries to stay numerous times at his home, the Pigeon House, in Orcop Hill. James eventually baptized Mary Ann.[61] In his journal, William Williams described in rapturous detail how he met and fell in love with Mary Brooks, a girl he met several times at church meetings.[62]

View of the area known as The Leigh, Glovcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

View of the area known as The Leigh, Glovcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Other great blessings occurred as remarkable spiritual experiences. As a young man, Francis George Wall worked in a blueing factory. Indigo blueing is poisonous, and the dust that collected in his lungs made him extremely ill, confining him to bed for months. As his condition worsened, the doctors did all they could for him, but finally they told his mother they did not expect him to live until the next morning. That night, the missionaries who were living with the family administered to Francis and gave him a blessing, promising that he would live to a great age and go to America, where he would help build towns, church buildings, and temples. The following morning, the doctor was astonished to find Francis sitting up in bed. Years later, ninety-five-year-old Francis wrote that all in the blessing had come to pass.[63]

Church members sought to move the missionary effort forward, even as they worked at their places of employment. Although not officially called as a missionary, Thomas Steed did his best to stand as a witness of Christ and share the gospel among those in his sphere of influence. He secured a job at a mansion named The Lodge in Malvern to earn money so he could emigrate to America with the Saints. When the owner, Mr. Campbell, discovered a Book of Mormon in his room, he tried to dissuade Thomas from his beliefs by furnishing him with anti-Mormon literature. Campbell also had the local minister visit Thomas to persuade him that his beliefs were wrong. But the attempt was unsuccessful. During Thomas’s first year working at The Lodge, the cook was converted to the restored gospel.[64]

Along with the blessings, these early Saints experienced tribulation and opposition. Many were the only members of their families who joined the Church, and some experienced direct family opposition. John Spiers’s brother persecuted him so much that John went to live with Daniel Browett in The Leigh, Gloucestershire. John’s mother was saddened by the rift between her sons, and she decided that the Church was the root of the sibling problem. Consequently, she also opposed the Church and its missionary work.[65]

In 1850, Jane Ann Fowler also experienced great persecution from her family as she investigated the Church in Herefordshire and became convinced of the truth of the gospel message. She recalled,

My parents and all my relatives persecuted me very much. My Father in particular. He thought I should obey him, he forbid me to go inside a Mormon meeting. I spent all the time I could reading and praying, and was convinced by the Spirit of the Lord that it was right, and the more I was persecuted, the more I felt I must be baptized. Father got so bitter he would not talk to me nor answer me. Then I would get a whipping.[66]

The Leigh parish Church in Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The Leigh parish Church in Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

At last Jane Ann’s father told her that if she was going to continue with the Mormons she should leave home, which she did. Ultimately, he told her not to call him Father again. After many trials, blessings followed. Over twenty-five years after Jane Ann had emigrated to America, her mother and father traveled to join her in the Bear Lake Valley in Idaho, an answer to her many prayers for her family. The summer after his arrival in the valley, her father was baptized.[67]

Mary Ann Weston Maughan described her sadness, because none of her family joined the Church: “My relatives did not obey the Gospel but they did not oppose me. This made me sorrowful and lonely. I attended all the meetings I could, often walking many miles alone to and from them.”[68] Unfortunately, loneliness was not the only suffering she endured due to her membership in the Church. Mary Ann Weston was married on 23 December 1840 to another convert, John Davis of Tirley, Gloucestershire, who was a cooper and carpenter. They were the only Latter-day Saints in Tirley and were instructed by Elders Woodruff and Richards to open their house for meetings. At the second meeting in their home, a mob arrived, beating and kicking John, who was injured internally. He was never well after this event, and soon afterward he had a fall. His health deteriorated until he died on 6 April 1841. Mary Ann’s physician advised her to leave and travel for the sake of her health, predicting that if she did not do so, she would shortly follow her husband to the grave. She stated, “The next day I left my home a sad lonely widow, where less than four months before I had been taken a happy bride. I did not go home, for I felt that my parents would try to stop me from gathering with the Saints. I had many homes offered me by friends, but I went to board with Mr. and Mrs. Hill of Turkey Hall. They were getting ready to go to Nauvoo.”[69]

Although the persecution of the Saints was not always in the form of physical abuse, quite often the temporal well-being of these new converts was put in jeopardy. For example, Francis George Wall, while working as a chore boy in the kitchen of a gentleman, began sharing Church books, including the Book of Mormon, with a servant girl who was also a Latter-day Saint. One day the lady of the house found the girl reading the Book of Mormon and asked where she got the book. As a result of sharing the gospel, Francis lost his job.[70]

Turkey Hall, Eldersfield, Worcestershire, home of Benjamin and Mary Hill. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Turkey Hall, Eldersfield, Worcestershire, home of Benjamin and Mary Hill. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Similarly, some of the Church members suffered by being deprived of temporal help or opportunity. William Williams wrote that he expected opposition from the world, but not from the Christian people around him. He explained that the clergy, landowners, and aristocracy would often give food and clothing to the poor, but they would withhold future help if they heard that those individuals or families had become associated with the Latter-day Saints. William’s family experienced this type of persecution.

In 1841 William went to visit his family who lived in Madresfield, Worcestershire. His father had worked on a farm there for over forty years, and his mother was a teacher at the Sunday School for the Countess of Beauchamp. William’s mother and brother had been baptized, and while William was visiting they often spoke of the gospel with friends and neighbors. A young girl in the neighborhood overheard their conversation and informed her mother that they were Latter-day Saints. The information was spread until it reached the vicar, the Reverend Thomas Philpotts, who wrote to the Earl of Beauchamp. By that same evening William’s father had orders to leave the home in six months’ time, and William’s mother was dismissed from teaching the Sunday School. One of their friends, Hannah James, lost her position as the lodge keeper for the estate when the vicar found that she too had joined the Church.[71]

According to William, the Reverend Philpotts went around the parish informing the people that the Lord punishes those who listen to the message of the Latter-day Saints and telling people not to rent a home to the Williams family. When he saw that the family would have no place to live, Philpotts approached William’s father and promised to help the family if they would cast off William. The father refused to do this, choosing to support his son.[72] The family must have moved eventually; they were listed in Madresfield in the 1841 census (about the time of the conflict with Reverend Philpotts), but by 1851 William’s widowed mother was a school mistress living in Leigh, Worcestershire.

Tracing Church Growth in the Early 1840s

One of the purposes of studying the history of the Church in the Three Counties was to learn more about the growth of the Church over time. As is widely known, the first year the gospel was preached in the area was a time of extraordinary growth. According to Wilford Woodruff’s reports of the conferences held in the area during September 1840, over forty branches had been organized in the first six months of preaching.[73] The available journals are not very specific about the continued growth of branches and conferences after the first year. Sources such as the Millennial Star and the British Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, along with results of the case study of the Bran Green and Frogmarsh branches, provide a little more insight into Church growth in the Three Counties.

One of the regular features published in the Millennial Star was the periodic report of regional and national conference meetings, which included membership numbers provided by representatives from branches and conferences. These reports are a fairly reliable source for the numbers of people participating in the branches at each conference, but they do not account for the number of people who had emigrated, apostatized, or moved to another area of the country in the first few years of their publication. Due to the way the information was reported, there may not be any way to know how many people left or were baptized between the reports.

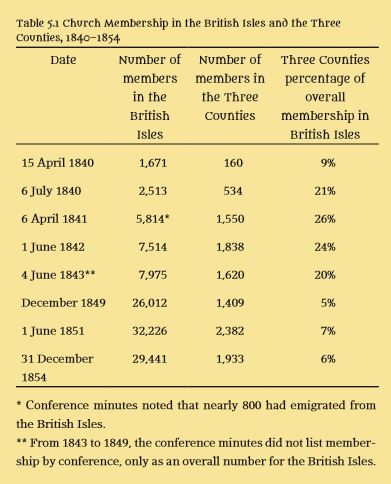

According to these conference reports, many changes took place during the first few years of the Church in Britain. Table 5.1 compares the number of members in the British Isles and the Three Counties area between 1840 and 1854.[74] By 15 April 1840, just over a month after Wilford Woodruff first arrived at John Benbow’s farm in Herefordshire, there were 160 members in the Herefordshire area, constituting 9 percent of the entire Church membership in the British Isles. Membership in this area increased dramatically from 1840 to 1843, reaching a high of 1,838 members in June 1842. This number composed 24 percent of the overall membership in the British Isles for that time period. Yet by 1849, the members in the Three Counties area decreased to 1,409, accounting for only 5 percent of the members in the British Isles, probably due to greater emigration and apostasy during the later 1840s. The lower percentage of members in the Three Counties compared to the rest of the British Isles in 1849 may be because other areas began to grow at faster rates while the majority of the United Brethren and its connections had been baptized earlier in the decade.

Branches and conferences changed with the fluctuation of Church membership in the area. On 14 June 1840, a number of branches were assigned to the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and a week later the Fromes Hill Conference was organized with over twenty branches.[75] Determining specific numbers of new members proved to be difficult in those very early days of the Church, as evident in the report by Wilford Woodruff from the June 1840 conferences. He wrote, “The different Branches in this region are so scattered, that it has not been possible to ascertain the number of members connected with each individual Church, but the whole number of the Churches connected with the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm, and the Froome Hill Conferences, together with a small Branch of 12 members, 1 Priest, and 1 Teacher at Little Garway, is 33 Churches; 534 Members; 75 Officers, viz.–10 Elders, 52 Priests, and 13 Teachers.”[76] The Church continued to grow rapidly in this area. When Brigham Young reported the conference meetings he held in December 1840, the Garway Branch had become the Garway Conference, with 95 members, and he stated that the total membership number was 1,261 for the Garway, Gadfield Elm, and Stanley Hill conferences.[77] The “Table of Nineteenth Century Church Units in the Three Counties” included in the appendix contains a detailed list of the branches and conferences.

The Cheltenham Conference is a good example of how the branch or conference boundaries changed over time. Sometime in 1841 or 1842, the name of the Gadfield Elm Conference was changed to the Cheltenham Conference, and changes in conference and branch boundaries continued from time to time.[78] During the next few years, the number of branches in the Cheltenham Conference fluctuated from seven to twenty, as some branches were reassigned to other conferences or new conferences were created. For example, in 1847, the following branches from the Cheltenham Conference were assigned to the new Edgehill Conference: Edgehill, Bran Green, Pouncel, Littledean, Woodside, and Vineyhill. Only Cheltenham, Apperley, Norton, Frogmarsh, Caudle Green, Compton, and Gloucester were left in the Cheltenham Conference.[79] By June 1848, however, the conference boundaries changed again, with the Edgehill and Chalford Conferences subsumed under the auspices of the Cheltenham Conference, bringing in the previous branches and adding the Kingswood, Cam, Tetbury, Avening, Chalford Hill, and Cirencester branches.[80]

Robert Ruck home in Hawcross, Redmarley D'Abitot, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Robert Ruck home in Hawcross, Redmarley D'Abitot, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Branch boundaries also changed over time as the number of members was continually increasing or decreasing due to baptisms and emigration. When Wilford Woodruff recorded the minutes from the first conferences in the Three Counties held in June 1840, the recorded branches were very similar to the congregations listed on the “United Brethren’s Preachers’ Plan”, showing that the creation of the branches naturally reflected the prior organization of the United Brethren.[81] These congregations may have been gatherings of family connections, friends, and neighbors, which could account for branches being located in small hamlets, sometimes within the same parish. For example, the Kilcot and Bran Green Branches were both located within the Newent parish boundaries, but they were far enough apart that the United Brethren had two different meeting places. Most branches were quite small, perhaps not including much more than an extended family group. In the report of the twenty-three branches of the Frome’s Hill Conference on 20 September 1840, only six branches had over fifty members, and eleven of them had fewer than twenty members. [82]

Many branches were in existence for only a short time, probably while a group of members were living in the area. If large numbers of people were not continually being converted, the branches would usually disband after a number of their members emigrated to America. The Bran Green and Frogmarsh Branches are examples of the influence a strong family can have in maintaining the Church in a certain area. The branch record lists the Robert Ruck and Thomas Oakey families, all of whom were children and grandchildren of William and Elizabeth Bromage Collett. The Colletts and their descendants accounted for 16 percent of the individuals in the branch records. The Oakeys and the Rucks were obviously influential in the branch. We found that 52 of the 118 members were baptized by either Robert Ruck or Thomas Oakey. The last ordinance listed in the branch records was recorded in 1856, the same year that Thomas Oakey’s family left for Utah.

Examining the lives of the early converts in the Three Counties has provided insight into several aspects of Church growth in that area. Although the baptismal records for the mid-nineteenth century are not complete, the information from the available membership records, the journals of missionaries and converts, and the conference reports found in the Millennial Star combine to paint a fuller picture of Church growth in the area. The added information from other public records, such as the census, emigration records, and civil registration, provide a greater understanding about the people who joined the Church. Although the exact number of Wilford Woodruff’s baptisms cannot be verified, the current estimates are very similar to those he reported. Obviously, Elder Woodruff’s work among the United Brethren and others living in the Three Counties area bore unanticipated fruit.

Notes

[1] Wilford Woodruff, in Journal of Discourses, 18:124. Edward Phillips, “Biographical Sketches of Edward and Hannah Simmonds Phillips, 1889, 1926, 1949,” 1, MS 11215, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. In the typescript of his autobiography, Edward Phillips stated that the one United Brethren preacher who did not join the Church was Philip Holdt.

[2] Wilford Woodruff, in Journal of Discourses, 15:343.

[3] Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal, 128.

[4] “Wilford Woodruff’s Baptismal Record, 1840,” in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:377–95. The “Baptismal Record” has no entries after 23 June 1840, when Wilford Woodruff left the area for a conference in Manchester. He continued to baptize people in Herefordshire, but he did not record their names, so he could have easily baptized six hundred people before he left England in 1841.

[5] John Gailey, “History of John Gailey, Undated,” 1, MS 11009, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. See also Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal, 126.

[6] Branch and conference membership records from the nineteenth century are available on microfilm at the Family History Library and the Church History Library in Salt Lake City. There are thirty-three different branch or conference records from the nineteenth century from the Three Counties. However, the British Mission manuscript history and historical reports 1841–1971 (LR 1140 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City) lists over 125 branches or conferences in the Three Counties during the nineteenth century. The table of branches in the appendix has more information about the branches. The manuscript history is also online at churchhistorycatalog.lds.org.

[7] For example, Wilford Woodruff’s baptismal record mentions that from 1–15 May 1840, “Elders Richards and Kington had Baptized 50.” Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:387. Additionally, John Spiers, James Palmer, John Needham, John Gailey, and James Barnes wrote of Henry Glover, Martin Littlewood, and William Kay, who preached with them at various times and for whom we have no written record. Presumably, many other priesthood leaders were also baptizing people without recording the information.

[8] Examples of published materials would be the autobiographies found in Kate B. Carter, comp., Heart Throbs of the West, 12 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1939–51), or Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage.

[9] Wilford Woodruff, “Baptismal Record 1840,” in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:377–95. According to Kenney’s note on page 377, “The Baptismal Record is a small notebook attached by a string to the inside of the second manuscript journal.”

[10] Not every name mentioned in Wilford Woodruff’s journal was included in the database unless there was some identifying information, such as a full name and dwelling place, or a place and date of priesthood ordination.

[11] By 1843, the missionaries for whom we have record either had emigrated to Nauvoo or were preaching in areas other than Gloucestershire, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire. We did not follow their records after they left the area.

[12] All of these sources are on the Internet. Censuses are found on FamilySearch.org or Ancestry.com. Birth, marriage, and death records for the United Kingdom are on Freebmd.org.uk or Ancestry.com. The ship passenger lists and other information for Mormon Migration is found at mormonmigration.lib.byu.edu. The Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel information is found at history.lds.org/

[13] John Spiers, “John Spiers Reminiscences and Journal, 1840–77,” 16, 16 April 1841, MS 1725, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Spiers wrote that Mary Fox was baptized on 31 March 1841.

[14] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:513–14, 517–19. At those conferences, the Bran Green and Gadfield Elm Conference had seventeen branches, with a total membership of 253. The Fromes Hill Conference reported twenty-three branches, with a total membership of 754.

[15] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 2:61–62, 66–69.

[16] Mormon Migration Index, http://

[17] “Conference Minutes,” Millennial Star 1, no. 12 (April 1841): 302. The minutes state that nearly eight hundred people had emigrated from the British Isles in the previous season, which number had not been included in the calculation of the number of members of the Church. We do not know if the emigration number includes children or only baptized members of the Church. The number of individuals could be greater than eight hundred. The Caroline originated from Bristol rather than Liverpool. In all likelihood, most of the passengers were from the Three Counties. Unfortunately, there is no passenger list to provide the number of emigrants.

[18] Thomas Steed, “The Life of Thomas Steed From His Own Diary 1826–1910,” 2, BX 8670.1 .St32, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Also online at https://

[19] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 4.

[20] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 4–5.

[21] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 5.

[22] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 5–6.

[23] John Gailey, “John Gailey, Reminiscence and Diary, ca. 1840–41,” 7–8, MS 1089, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[24] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 1–2.

[25] John Needham, “John Needham Autobiography and Journal, 1840 August–1842 December,” 53–54, MS 25895, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Unfortunately, on page 53, when he was describing the family, Needham gave no identifying information about Sister Smith other than the fact that she had a married daughter named Sister Taylor, who lived in West Bromwich, Staffordshire. We were not able to identify Sister Smith in our list of converts.

[26] Needham, “Autobiography,” 55–56.

[27] Needham, “Autobiography,” 57. The hymn “The Spirit of God” was written for the Kirtland Temple dedication on 27 March 1836. Sister Smith would not have known the song except through her dream, because the first missionaries to England did not arrive until the summer of 1837.

[28] Needham, “Autobiography,” 57.

[29] William Williams, “William Williams reminiscence, 1850,” 3–4, MS 9132, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Spelling and punctuation are in the original.

[30] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 4.

[31] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 5.

[32] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 5–6.

[33] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 6.

[34] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 6–7.

[35] Mary Ann Weston Maughan, “The Journal of Mary Ann Weston Maughan,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:353–54.

[36] Charles Sansom, “Journal of Charles Sansom, 1826– 1908/

[37] Sansom, “Journal,” 3.

[38] FamilySearch.org’s Family Tree often provided relationship information that is not always available in the journals or branch records. Just over half of the branch members had parents’ names listed in the records, but the journals very rarely mentioned family relationships. Because Family Tree is a compilation of genealogies submitted by descendants and researchers, the records have not been verified. However, in spite of the possibility of error, there is more information about the converts submitted by their family members than can be found in other public records. Thus, when identifying the converts’ names in FamilySearch, we also looked at other family members connected to them, searching for relationships with others that might be in our database.

[39] “United Brethren Preachers’ Plan of the Frooms Hill Circuit, 1840”, 248.6 U58p 1840, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[40] FamilySearch Family Tree helped us identify these family relationships, although sometimes we found the families living near each other on censuses. We also found many of the families listed together on the Mormon Migration website or on the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel website.

[41] Ronald W. Walker, “Cradling Mormonism: The Rise of the Gospel in Early Victorian Britain,” BYU Studies 27, no. 1 (Winter 1987): 29.

[42] Philip A. M. Taylor, “Why did British Mormons Emigrate,” Utah Historical Quarterly 22, no. 3 (July 1954): 260–62.

[43] Job Smith, “The United Brethren,” Improvement Era, July 1910, 819.

[44] While Bran Green and Frogmarsh were separate branches in 1840, their records were combined at some point during the period from 1840 to 1856. The “British Mission Manuscript History” shows that the Bran Green Branch disbanded in 1848. With the number of duplicate individuals listed on both sets of branch records, it appears that the branches became one or at least their records were combined at some point. The membership records for these two branches are available in the Family History Library: Film # 86991 Items 15–16, and Film # 86998 Items 17–18.

[45] Bran Green and Frogmarsh are spelled different ways, depending on the record. Bran Green is written as Brangreen, Brand Green, or Brandgreen. Frogmarsh is sometimes spelled Frogsmarsh. We will consistently use Bran Green and Frogmarsh unless the record to which we are referring spells the names differently. Today, the maps show these hamlets as Brand Green and Frogsmarsh.

[46] One important note about this database is that not all the names on the branch records have a corresponding baptismal date. Some individuals are listed in the records because they were blessed as children or they moved into the area or they were excommunicated. Hence, no baptismal date is listed.

[47] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:440 (16 April 1840).

[48] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 1.

[49] Frederick Weight, “A Brief History of the Life of Frederick Weight by himself,” 4–5, MSS SC 3200. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[50] V. Ben Bloxham, “The Apostolic Foundations, 1840–1841,” in Truth Will 139–40. Wilford Woodruff also wrote that when he went to visit the Benbows on 10 April 1840, he “found Broth John Benbow had sold his possessions & entirely left the Hill farm and taken up his abode of a season at Frooms [sic] Hill.” Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:433 (10 April 1840).

[51] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:490–91 (11 August 1840).

[52] The advertisement of the auction of all his farm implements and possessions shows that he wanted to sell cattle, farming utensils, sacks of grain, and casks of cider. “Moorend Farm, Castle Frome, Herefordshire, To Sell By Auction,” Hereford Times, 27 March 1841.

[53] Maughan, “Journal,” 348–49.

[54] Emily Hodgetts Lowder, “Emily Hodgetts Lowder—103 years,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 7:424.

[55] When possible, we used the occupation listed in the 1841 census rather than the Mormon Migration Index because the census was more likely to reflect the social status of the family in England. The ships lists were more likely to be self-reported data, allowing someone to state the occupation as something that was not reflective of their social station. For example, John Cheese and Thomas Kington both listed their occupations on the passenger list as “preacher.” However, an itinerant preacher for the United Brethren probably did not receive the same level of respect from society as a minister from the Church of England. Similarly, another emigrant, Richard Lilley, was an agricultural laborer on the 1841 census, but on board The Chaos in late 1841, his occupation is listed as “farmer.” Agricultural laborers performed farming work, but he was probably not in the same social class as John Benbow, a gentleman farmer who hired agricultural laborers. When the only record of occupation was from the Mormon Migration Index, we had to use the label “farmer” with caution, knowing that perhaps those individuals were not in the same social class as farmers in the 1841 census in England.

[56] Susan L. Fales, “Artisans, Millhands, and Labourers: The Mormons of Leeds and Their Nonconformist Neighbors,” in Mormons in Early Victorian Britain, ed. Richard L. Jensen and Malcolm R. Thorp (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1989), 163.

[57] A Vision of Britain Through Time, “Statistical Atlas, Social Structure,” www.visionofbritain.org.uk/

[58] According to the manuscript history and the branch records held at the Family History Library (Salt Lake City), branches were established by 1841 in the larger towns listed, but apparently, the missionaries whose diaries are available did not baptize many people there. See “Nineteenth-Century Church Unites in the Three Countries” in the appendix for the dates of branch organization.

[59] Walker, “Cradling Mormonism,” 29.

[60] In FamilySearch.org, the birth years are actually christening years because there were no birth records at the time. Christenings might not have occurred when the child was an infant. If there was no birth date, we did not know if the year was correct. When there were census records to corroborate the dates, we were more confident in the birth years listed. If the only age we had was from the 1841 census, we knew that the individual could have been older than listed, but we used the birth year listed in the census. The 1841 census usually rounded down to the fives for anyone over the age of sixteen, so that the age of a twenty-four-year-old was usually recorded as twenty.

[61] James Palmer, “James Palmer Reminiscences, ca. 1884–98,” 50, MS 1752, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[62] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 14–18.

[63] Francis George Wall, “Francis George Wall–Pioneer of 1863,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 7:363–64.

[64] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 6–7.

[65] Spiers, “Reminiscences,” 2.

[66] Jane Ann Fowler Sparks, Jane Ann’s Memoirs, comp. Marsha Passey (Montpelier, ID: M. Passey, 2004), 4; emphasis in original.

[67] Sparks, Memoirs, 13.

[68] Maughan, “Journal,” 354.

[69] Maughan, “Journal,” 356.

[70] Wall, “Journal,” 363.

[71] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 11–12.

[72] Williams, “Reminiscence,” 12–13.

[73] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:519.

[74] Initially we wanted to examine Church growth in the Three Counties for the twenty-year period of 1840–60, but we found that there were no statistical reports listed in the Millennial Star from 1856–60 for this area.