Emigrating or Remaining in England

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, “Emigrating or Remaining in England,” in The Field Is White, Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 137-172.

Chapter 5 described the converts’ stories as the Church began its development in the Three Counties. This chapter focuses on what they did after they joined the Church: whether they emigrated to America or remained in England, and whether they remained faithful to the Church throughout their lives or eventually became less active, inactive, or even hostile as their lives continued. Many descendants of these converts from the Three Counties have anecdotal data about their own ancestors, but our journal database and branch database provide more information about the group as a whole. Another useful source has been the conference reports from the Millennial Star, which supply additional data regarding the rate of emigration from the Three Counties. The first part of the chapter will describe the database findings about the converts’ emigration to America, as well as whether they followed the body of the Latter-day Saints to the western United States. The second part will look at converts who stayed in England, including possible reasons why they chose to stay, along with information from journals and the databases concerning apostasy among them.

At the funeral for William Pitt in 1873, Wilford Woodruff described the converts from the Three Counties: “There has been less apostasy out of that branch of the Church and kingdom of God than out of the same number from any part of the world that I am acquainted with.”[1] As examples, he mentioned some of his friends and companions from the Three Counties who had emigrated to Nauvoo and later traveled and settled in Utah. Thomas Kington, John Benbow, and William Pitt left England within the first year of hearing the gospel and made their way to Nauvoo, eventually becoming part of the exodus from Nauvoo and crossing the plains to settle in Utah. Other former United Brethren members, including Edward Ockey, John Spiers, James Palmer, Edward Phillips, and Robert Harris, also left England for Nauvoo in the early 1840s, and followed the path of the Saints to Utah and Idaho. While Wilford Woodruff may have seen that most of the people he remembered from the Three Counties remained faithful to the Church, his statement cannot be verified without comparing the lives of all the converts. However, there is no way to know who all the converts were, let alone to identify them in other records sufficiently to make a judgment on their faithfulness as a group. The journal and branch databases do allow us to trace the movements of the converts to get a general sense of how many emigrated or stayed in England. These databases, considered along with other records and journals, provide greater insight about their strength and faithfulness to the restored gospel as praised by Wilford Woodruff.

Following Those Who Emigrated to America and Trekked West

Because of the stories of many pioneers who joined the Church and then traveled to join the Saints in Zion, Latter-day Saints may think that emigration was the norm for the early members of the Church in England. However, the databases developed for this study and the emigration reports in the Millennial Star demonstrate that the call to gather to Zion was heeded by some and not by others. Some were full of zeal, as evident at the 12 March 1848 Worcester Conference: “Elder Butler then arose and stated that he was happy to state that the long-wished for time had arrived when the Saints were called upon to gather home unto Zion, and if we cannot get the people to believe by precept, the time will soon arrive when we will teach them by example, by going out from their midst unto a land of refuge, whilst the overflowing scourge passes over the nations.”[2] From the perspective of Church leaders in the mid-1800s, the choice to emigrate to Zion appears to have been a part of the measure of Church members’ faithfulness.

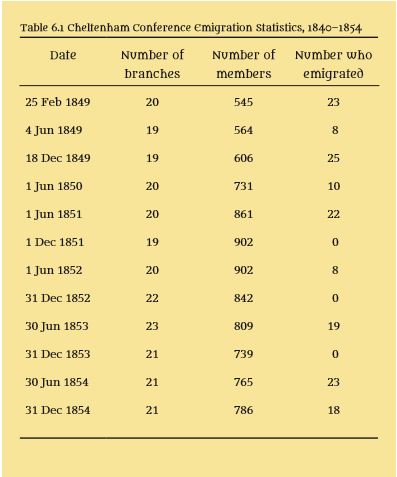

The Millennial Star began recording emigration statistics in 1848. Table 6.1 shows the number of emigrants from the Cheltenham Conference listed in the reports from 1848 to 1854. After 1854, the emigration statistics were for the British Isles overall, rather than for each individual conference. The table demonstrates that from 1848 onward, the members from the Cheltenham Conference were not emigrating in large numbers; the largest number of emigrants from this conference for a six-month period was 25 in 1849. As there were 606 members in the conference, 25 emigrants would be a small percentage of the whole. The conference report for 30 June 1853 shows that during the first six months of 1853, only 19 members emigrated from Cheltenham, but 114 emigrated from Herefordshire and 48 from Worcestershire. The total from all three counties who left during that six-month period was 181.[3] Obviously, the Millennial Star reports are inadequate for understanding the emigration rate or the situation of the Three Counties. Adding information from the databases enabled us to gain a more accurate perspective of emigration in the Three Counties, along with some details of emigration that occurred before the Millennial Star began reporting it in 1848.

The journal database reveals that of the 577 people who were positively identified, 34 percent were listed on ships’ passenger lists found on the Mormon Migration website. Often, the emigrants were traveling on the same ship with family members and friends from the Three Counties. The North America, one of the first ships of Mormon emigrants, left Liverpool in September 1840 with 28 passengers listed in our journal database. Although children younger than eight are not listed in our databases, the passenger list includes many children and other relatives of those 28 people, increasing the number from the Three Counties on that ship. In fact, Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal that John Benbow generously paid the expenses for 40 of the local Saints to emigrate to America.[4] When we added in the family members of those in the database who are also on the passenger list, we found 43 total emigrants from the Three Counties, some who probably paid their own way.

Statue on a Liverpool dock commemorating the emigration of Latter-day Saints. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Statue on a Liverpool dock commemorating the emigration of Latter-day Saints. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Mormon Migration lists several ships in the early 1840s that did not have complete passenger lists.[5] For some of these ships, the only way we know there was a group of Church members on board was because of the diaries or autobiographies that are available. For example, there were three trips in 1841—one voyage of the Harmony and two voyages of the Caroline—embarking from Bristol, Gloucestershire, which would have meant that most of the passengers probably came from the Three Counties. Unfortunately, the only passengers’ names listed for the Harmony are the twenty-nine individuals who happened to be mentioned in the diaries of two passengers, James Barnes and Mary Ann Weston Maughan. Similarly, while Edward Phillips’s history stated that there were one hundred in their company on the Caroline traveling from Bristol to Quebec in August 1841, Phillips only mentioned himself and the group leader by name.[6] The other voyage of the Caroline in January 1841 recorded no passenger names, but the Millennial Star reported that a group from Herefordshire and the surrounding area left Bristol at that time.[7]

Several other ships in the early 1840s likewise had no complete passenger lists. Because of the lack of official listings, we had to assume that if FamilySearch showed places of marriage or death in America, or if the United States census or the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel website included these individuals, they must have emigrated to America. These other records were particularly helpful for identifying the converts who married or died in Nauvoo, Illinois, the intermountain west, or any place in between. In addition to those individuals listed on Mormon Migration, we found another 81 individuals from the journal database for whom there is evidence of emigration based on their later life events, although their names did not appear on a passenger list. The total percentage of emigrants for the journal database came to 49 percent, or almost half of all those individuals noted in the journals.

Unlike the journal database, the database for the Frogmarsh and Bran Green Branches showed an emigration rate of only 30 percent. Several possibilities may explain why fewer people listed in the branch records emigrated. If the individuals were still in England by the time the branch records were written in the mid-1840s, these individuals may have been too old, too infirm, or too poor to leave earlier, or they may have had family concerns or other issues that were keeping them in England. Perhaps by the time they were able to deal with the difficulties that prevented them from emigrating in the early 1840s, they may have decided they could not leave home for other reasons. The earliest emigrants listed in the branch records were the Thomas and Comfort Boulter family, who left in 1849, while the rest of the emigrants from the branch left from 1855 to the 1880s.[8]

Pastoral scene in Newent, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Pastoral scene in Newent, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The Thomas and Ann Collett Oakey family left from the Frogmarsh Branch. Their daughter, Sarah Ann Oakey Ludlum, later recounted the family’s experience as they left their home in Eldersfield, Worcestershire, and sailed to New York City in 1856 aboard the Thornton. The family traveled with their fellow emigrants to Iowa City where they became part of the ill-fated Willie handcart company. Sarah and most of her family miraculously survived the ordeal of the trek, but her eleven-year-old sister Rhoda perished as they were about to enter the Salt Lake Valley.[9]

Family Trials. Personal histories of the Latter-day Saints from the Three Counties show that many of them desired to gather to Zion, first in Nauvoo and later in Utah. Carrying out this desire was sometimes difficult because a large number had to leave their families and friends. However, despite all the trials associated with leaving England and undertaking a hard journey, they also had a sense of happy anticipation. Jane Ann Fowler Sparks described her experience when she was seventeen years old and traveling without her family:

To travel to Utah with no means and only my heavenly father for a friend, but I never felt happier in all of my life than I did at the time. My saddest grief was in leaving my dear mother and my only sister. . . .We were four green horns, as they would call us in this country [America], but we were full of faith and did not realize the trials we were going to pass through before we reached our journeys [sic] end.[10]

The previous chapter shared the sad story of Mary Ann Weston Maughan, whose first husband had been brutally beaten by a mob soon after their marriage. After his death soon thereafter, Mary Ann settled her business, and in May 1841, she left with a group of Saints bound for Nauvoo. As she bade her family farewell, her mother was brokenhearted, and her two little sisters “clung around my neck, saying ‘We shall never see you again.’” She recorded that she could “never forget” the grief and sorrow that she experienced at parting with her family.[11] While she and her party were preparing to sail from Bristol, Mary Ann’s father sent lawyers to find the “young widow dressed in black” on board the ship to persuade her to come home. Having been warned previously that the lawyers were coming, she laid aside her black clothing for more cheerful attire, and in so doing she went undetected.[12]

Dovecote, Pigeon House Farm, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Dovecote, Pigeon House Farm, Eldersfield, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Emily Hodgetts Lowder came from a wealthy family, all of whom, with the exception of her father, joined the Church. In 1856, their mother thought it best for them to emigrate without her husband’s knowledge. The plan was for the wife and daughters to travel to Liverpool while their father was away from home for a few days, leaving William Ben, who was recovering from an illness, to stay at home to tell the father about their emigration. Emily recounts the events that transpired:

When Father received the news he hastened to Liverpool with officers. He followed us, as we were still in the Irish Channel and not yet on the open sea. Father paid the captain of the vessel one hundred sovereigns to cast anchor for one hour. We all hid. His time was about expired when Mother finally gave herself up. He did not force Mother to go back but, through kind persuasion, telling her that he would sell out and come to Utah, she went home with him. I was fifteen and my sister, Maria, was seventeen. We came on alone to Boston.[13]

Apparently, the emigration of the Hodgetts family was sensational enough that it was described in the newspapers. The newspaper account was somewhat different from the daughter’s recollection, however, indicating that Mrs. Hodgetts had taken a great deal of cash and portable property with her when she left home.[14] After recovering from his illness, Emily and Maria’s brother William Ben arrived in Boston ahead of them by taking a fast steamer. Emily continued:

William Ben brought a letter from Mother telling us what to do. This letter I kept until it fell to pieces, reading it often and crying. . . . In the letter she said, “Maria, come home and take care of your mother in the hour of trial, my days are short. Emmie, my loved one, go to Utah with your brother and keep faithful, work in the house of the Lord. William Ben, be a guide and protection to your sister, tenderly watch her footsteps.” Maria stayed in Boston two weeks then returned to England. My brother and I came on to Utah. Mother only lived a few months after Maria’s return home.[15]

Emily and William Ben made their way to Salt Lake City in a wagon train following the Willie and Martin Handcart Companies in 1856, suffering much from the harsh winter weather. In 1860, when she was only nineteen years old, Emily married, and her brother William died.[16]

Albert Dock in the port of Liverpool. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Albert Dock in the port of Liverpool. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Travel Trials. Even when people were on their way to Zion, they were not free from difficulty, often suffering sickness, deprivation, and death on the voyage across the ocean and the journey to Nauvoo or Utah. Francis George Wall arrived in New York with his parents and two sisters in 1863. While the family was on a train from New York to Missouri, one of the train cars caught fire, burning much of the passengers’ luggage. The train officials received five thousand dollars from the railroad company to cover the loss, but when the Saints tried to get money for their losses, the train officials refused to give them any compensation.[17]

Mary Field Garner tells of being seasick during the whole voyage across the Atlantic, which took seven weeks because the ship was driven off course.[18] Illness was often a problem for the travelers because they lived close together in cramped quarters on board the ship. Sarah Davis Carter recalled: “While crossing the ocean on the ship Windermere, smallpox broke out. My two brothers, Rhuben and Levi, both died from this dreadful disease and were buried in the sea. It almost killed my mother to see those two darlings, with weights attached to their feet, slide into those shark-infested waters.”[19]

Sarah said that when they arrived in New Orleans, an elder of the Church escorted those Saints who had recovered from the smallpox but were left with ugly scars on their bodies to an emigrant home. Not wishing to be associated with them, he made them walk on the other side of the road and instructed them not to speak to him. Sarah’s grandmother was so upset at his behavior that she predicted that he would “die in a ditch.” Sarah confirmed that he later became a drunkard and died in a gutter.[20]

Home Connections. As the English Saints from the Three Counties arrived in Nauvoo, many of them settled near to their acquaintances from England. For example, Edward Phillips said that he “boarded with an old friend by the name of Jenkins.” There he met his future wife, Hannah Simmonds, also from Gloucestershire, who was living with Benjamin and Mary Hill, formerly from Eldersfield, Worcestershire. Hannah and Edward were married in the presence of Benjamin and Mary Hill by Heber C. Kimball in 1842.[21]

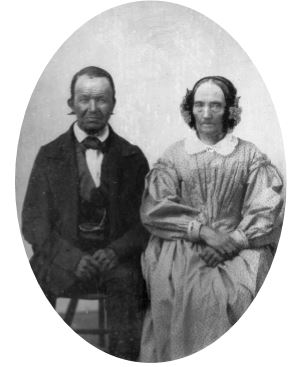

George and Mary Bundy, Job Smith's uncle and aunt. (Church History Library.)

George and Mary Bundy, Job Smith's uncle and aunt. (Church History Library.)

Similarly, George Bundy and his nephew Job Smith from Redmarley, Worcestershire, lived with Daniel Browett from the Leigh, Gloucestershire, for the first six weeks they were in Nauvoo. Then they lived with Charles Price, a former United Brethren preacher, and then with John Newman, who was originally from Deerhurst, Gloucestershire. Some of the English converts used this network of friends to obtain employment. George Bundy and Job Smith secured jobs working at the Nauvoo brickyard for a dollar a day under superintendent Frank Pullen from Ledbury, Gloucestershire. They finally settled on a quarter section of land where several families of their English acquaintances also lived.[22]

Job Smith eventually left Nauvoo and traveled west with the Latter-day Saints to Salt Lake City. Soon after arriving, he was called to return to England on a mission where he labored in the Norwich Conference. While in England, he visited many of his relatives who were still living in Hawcross and Redmarley, Worcestershire. While on this mission, he met his future wife Adelaide Fowles in Bedfordshire, England.[23]

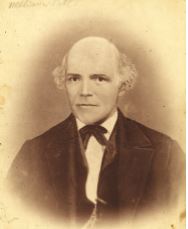

William Pitt had been a musician in the Dymock, Gloucestershire, Anglican parish church before he was baptized by his brother-in-law, Thomas Kington, on 13 June 1840. In Nauvoo, Pitt was able to use his musical abilities for the good of the community as he became leader of the Nauvoo Brass Band. The Nauvoo Brass Band played at significant occasions in Nauvoo, including the procession as the bodies of Joseph Smith and Hyrum Smith arrived in Nauvoo from Carthage Jail. As William Pitt traveled west with the Saints, he and his brass band often played concerts in small settlements in Iowa to provide money and provisions for the pioneer trek. Along the way west and upon arrival in the Great Salt Lake Valley, music from the band, under the direction of William Pitt, was an important way to enliven the spirits of the weary pioneers and to provide beauty for Church meetings and other events.[24]

As a young man, Thomas Steed emigrated to America, arriving in Nauvoo on 13 April 1844. Some of his relatives had already arrived and were available to greet him. He recalled his arrival:

The prophet Joseph Smith was at the pier. At first glance I could tell it was him, by his noble expression. He came on board to shake hands and welcome us by many encouraging words, and express his thankfulness that we had arrived in safety. As he could not stay with us, he sent Apostle George A. Smith to preach on board. “What did you come here for?” asked he. “To be instructed in the ways of the Lord,” answered someone. “I tell you, [Elder Smith said] you have come to the thrashing floor, and after you have been thrashed and pounded you will have to go through the fanning mill, where the chaff will be blown away and the wheat remain.” (The troubles in Nauvoo were just coming upon them.)[25]

William Pitt. (Church History Library.)

William Pitt. (Church History Library.)

Thomas immediately joined the Nauvoo legion, belonging to the company captained by John Cheese, who was also from the Three Counties.[26] After Joseph Smith’s martyrdom and the Saints’ expulsion from Nauvoo, Thomas made his way to Utah with some of his relatives, finally arriving in 1850 and settling in Farmington.[27] Thomas served as part of the rescue party that went out to help the struggling Willie and Martin handcart companies in 1856. His twenty-year-old niece Sarah Steed was in the handcart company and survived the ordeal.[28] Thomas’s father never emigrated to America, possibly due to his ill health, but he died in the faith in Malvern, Worcestershire, in 1855. Thomas’s mother began her journey to Utah in 1857 after her husband died, traveling with her married daughters, Rebecca and Ann. The ocean voyage was too much for her, and she died an hour after disembarking in Boston.[29] In 1875, Thomas went back to England on a mission and experienced a joyful reunion with several of his family members, many of whom had joined the Church when he did but had stayed in Malvern, Worcestershire.[30]

Faithfulness Amid Suffering. The story of the Field family from Stanley Hill, Herefordshire, reflects the tragedies and suffering the early Saints faced after they arrived in Nauvoo and were then forced to leave for the West in order to remain faithful to their convictions. Mary Field Garner recorded that her father did not have enough money to buy a home when they arrived in Nauvoo, so they rented one from a fellow Latter-day Saint. Mary faced the sadness of having her father and two sisters die in Nauvoo, leaving her mother with six children to rear. They were very poor and survived on one pint of cornmeal per day for the seven of them. She lamented, “OH! How hungry we were for something else to eat. The children cried for a piece of white bread, and mother, oft times, would cry with us, as she was unable to give us the bread or get enough food to satisfy the hungry cries of her children. The Saints were very kind to us and tried to help us the best they could.”[31]

The sadness of destitution was sometimes accompanied by spiritual blessings. After the death of Joseph Smith in 1844, Mary was present at the meeting where Brigham Young took on the appearance and voice of Joseph Smith, showing the people that the mantle of Joseph Smith had fallen on him. She recounts, “I had a baby on my knee who was playing with a tin cup which fell on the floor just after [Brigham Young] arose to speak. Mother stooped over to pick it up. We were startled by hearing the voice of Joseph. Looking up quickly we saw the form of the Prophet Joseph standing before us. Brother Brigham looked and talked so much like Joseph that for just a minute we thought that it was Joseph.”[32] Edward Phillips from Gloucestershire, corroborated this experience: “I . . . heard with my own ears and saw with my own eyes. We all thought Joseph had come back to us although we knew he was in his grave.”[33]

In September 1846, the Field family crossed the Mississippi River as the Saints were forced out of Nauvoo by the mob. They were too destitute to travel west with the Saints, so they lived with several other families who were in a similar desperate situation on Nickerson Island in the middle of the river. During that winter, the mob sent word that the stranded people could return to their homes so that they had decent shelter. They continued to live in this quiet, deserted town for two more years. One night in 1848, Mary’s mother witnessed a heartbreaking event as she went to the pump to get water.

She heard a terrible crackling of timber. Looking up she saw the beautiful Nauvoo Temple in flames. She ran back into the house, waking us children and also the Lee family [with whom they stayed] and several neighbors to watch it burn to the ground. It is impossible to describe our feelings to see our sacred temple, which we were so proud of and which had cost the Saints so much hard work and money to build, being destroyed. The anti-Mormons were also angry about it, as they were proud to have this beautiful structure in the community.[34]

The next spring, the Field family started west, staying two seasons at Council Bluffs, Iowa. As they journeyed west, an Indian chief was attracted to Mary, who had red, curly hair hanging in ringlets down her back. He offered many ponies for her, but her mother refused and later hid her under a feather mattress as the chief followed the camp for several days. The mother informed the chief that Mary was lost. He hunted through the wagons to find her and even felt the mattress but failed to detect her. After staying all day to see if she came back, he finally left when night came. Mary and her family arrived in the Salt Lake valley, and the chief managed to find her there sometime later. He was again rebuffed and finally left for good after three days.[35] In spite of all her trials, at the end of her life Mary Field Garner stated, “I am glad my parents embraced the Gospel in England and came to Zion.”[36] Mary died at the age of 107 in 1943, true to her beliefs. At her funeral, her previously-written testimony was read:

It is said I am the only living witness to have actually seen and known the Prophet Joseph Smith and I want to bear my testimony to the world and especially to every Latter-day Saint to the truthfulness of this Gospel as revealed through the Prophet Joseph, that Jesus Christ is the Savior of mankind, that Joseph Smith was a true and living prophet of God, that he was divinely called of God to establish His true Gospel on this earth in this last dispensation, that he was a true and faithful leader of the Saints and that the principles he advocated were true and correct beyond a doubt, that he lived the Gospel as he taught it to his people, that he did seal his testimony with his blood, that I was in Nauvoo at the time of the martyrdom and I did see their bodies returned to Nauvoo to be prepared for burial, that I did view the bodies before they were buried.[37]

Many Latter-day Saints who emigrated from the Three Counties lived in the Nauvoo area at first. The journal database affirms that 65 percent of the 282 emigrants arrived in America prior to 1846, at which time the body of the Saints left Nauvoo and began to move west. The rest of the emigrants represented in the database were part of the Mormon pioneer migration to Utah. The majority (61 percent) of all the emigrants from England were listed either in the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel website, having traveled west before 1869, or in reports or narratives of their later life events in Utah or Idaho. We found 137 of the people in the database listed on Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, with evidence of another 40 who traveled west either in an unrecorded pioneer company or on the train after 1869. Sixty-three of the English emigrants from the database did not arrive in Utah because they had died (1) while they were en route on the ship, (2) in either Nauvoo or Missouri before their trek west began, or (3) somewhere on the plains as they traveled with the Saints. We assume these individuals were true to the gospel because they were following the Saints, even though they did not reach their intended destination.

Nearly half of the converts from the Three Counties demonstrated their faithfulness by following the prophets and staying true to their convictions as they emigrated to Nauvoo and the western United States. These Saints contribute evidence to support Wilford Woodruff’s statement that those he taught in England remained fully involved in the Church. However, not all of those who arrived on the American continent made it all the way to Nauvoo or later to Utah.

Different Destinations. Twenty-five of the individuals in our database crossed the ocean to joint eh Saints but did not finish the journey to Nauvoo or to the Salt Lake Valley. Their names were on censuses or other records in the Midwest in the 1860s or later. Some emigrants may have stopped either because they needed to work or because they gave up their quest when faced with the trials of the journey. William Clayton was on the North America in 1840 with the first group of converts from the Three Counties. His description of the journey to Nauvoo related that after arriving in New York, the emigrants had to travel over land and by boat on lakes, rivers, and canals through New York, Ohio, and Illinois. Several families decided to stay for a time in other communities, some to work to make enough money to continue the trip. Clayton stated that some in his group were tired and sick, but others became disgruntled, “inclined almost to wish they had not left England.” Several families decided to leave the group and stay in Kirtland, Ohio, for a season, “cheerful and rejoiced in the prospect of soon having a place to rest.” William Clayton wrote that all of them dropped out of the group receiving a letter of recommendation to go to Kirtland, except for Thomas Hooper from Herefordshire, “whose conduct has been very bad.”[38] Thomas and his wife, Hannah, were both baptized by Wilford Woodruff in England, but aside from being mentioned in William Clayton’s journal, they cannot be found on other records associated with the Latter-day Saints. Either they both died soon after leaving the group or they stayed in Ohio or another area and did not rejoin the Saints.

Some people listed in the journal database lived in Nauvoo but never left Illinois to go west with the Saints. One of these was the widow of John Cheese. John was one of the first to join the Church in Herefordshire, and although there is no death record for him, he most likely died in Nauvoo. Mary Cheese had remarried and was recorded as living in Nauvoo in the 1850 census with two of her children, both of whom had come from England with her.[39] Mary could not be found on later census records, but her children married and stayed in Hancock County, Illinois. Those who stayed in the midwestern states may have apostatized from the Church or they may have been merely too tired or too poor to move west. Without details from their own lives or their family stories, there is no way of knowing their reasons for not following the body of the Church west.

We were surprised to find that six of the Saints from our database who lived in Nauvoo returned to England. The public records cited in our database do not provide enough information to discern whether their return was a result of disillusionment and apostasy from the Church or due to family or economic situations that would have affected their choice. John Spiers’s journal mentioned the William and Susanna Margetts family as being apostates who returned to England from Nauvoo.[40] In contrast, John and Lydia Pullen Fidoe lived in Nauvoo after they left England in 1841, were back in Bishops Frome, Herefordshire, in the 1851 and 1861 censuses, but eventually died in Ohio in the 1880s. The obituary for John Fidoe in the Deseret News in Utah in 1881 mentions that because John had been in the Navy earlier in life, he enjoyed traveling, perhaps accounting for the return to England. The obituary states, “He died in full faith of the gospel,” in Ohio.[41]

Those Who Remained in England

Samuel Eames. (Church History Library.)

Samuel Eames. (Church History Library.)

Many people may assume that converts who emigrated were more faithful to the gospel than those who did not. Evidence demonstrates that emigration may not be the only proof of a convert’s strength of testimony, and lacking desire to follow the call of the prophets to gather in Zion was not the only reason individuals may not have emigrated. The database by itself cannot answer the question of whether those who stayed in England were still committed to the Church, but one should not discount the faithfulness of those individuals who stayed in England.

Without knowing their hearts and minds, those in the present day cannot say whether those who stayed behind were less faithful to their baptismal covenants than those who emigrated. On his mission to England in 1851, Job Smith traveled to the Three Counties to visit relatives. He recorded that his grandfather, William Smith, was still living in Deerhurst and was an elder in the Church, but that he was over seventy years old and in very poor circumstances.[42] William Smith had obviously remained active in the Church but had not been able to join the Saints, likely due to poverty, age, or health concerns. This example demonstrates reasons that at least some of those who were faithful to their covenants remained in England. Additional reasons might have included caring for a sick family member or being married to someone who was not a member of the Church, as well the possibility of individual apostasy. Converts dealing with any of these situations except apostasy might have remained faithful to the gospel throughout their lives, even if they did not join the Saints in America. The public records and anecdotal information from journals and autobiographies of missionaries and members provide examples of all of these reasons for staying in England.

Reasons for Not Emigrating. Some families who joined the Church early in the 1840s were not able to emigrate as soon as they desired or not at all because of poverty. Some converts from the early years had to wait many years before they had a chance to join the Saints in Utah. William and Elizabeth Bishop Davis, who had been members of the United Brethren, were baptized by Wilford Woodruff in 1840. Their daughter Sarah recollected, “My father’s wages were small and . . . his family was large. . . . We knew if we emigrated to Utah, which was the great desire of our hearts, we would have to save every penny that we possibly could.” [43] They worked for many years and were finally able to save enough money to emigrate in 1854.

Home of Samuel Eames in Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Home of Samuel Eames in Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Another stalwart member who had to wait and work was Samuel Eames of Garway Hill, Herefordshire, who was not able to emigrate until the end of his life. Many years earlier Samuel had “sold all [he] had and devided [sic] the money and . . . sent 4 of [his] Children to America.”[44] Samuel, his wife, and their son John stayed behind in England for over twenty-five years. In a letter to his children in America, Samuel expressed his desire to die in America. He was finally able to travel over the sea and across the plains to Utah in 1868. He died two months after his arrival.

Being poor and unable to emigrate did not prevent converts from continuing active membership in the Church. William G. Davis was a missionary in the Three Counties in the 1880s, some forty years after Wilford Woodruff had first preached the gospel there. He met several people who had been baptized in 1840, including some who are listed in our journal database.[45] His journal details his experiences with the Saints, confirming some of the assumptions we had made about those who remained in England after being converted. For example, he described some of the Church members he visited as being “in a very poor condition,” but generous to the missionaries.[46]

Some members who might have had finances sufficient to emigrate did not do so because of family problems and responsibilities. The Pritchard family had responsibilities that kept them from emigrating. They had been members of the Church for several years when Davis arrived. Davis wrote that they desired to emigrate, but their elderly father lived with them: “The family will not emigrate while he lives. Although they could raise the means. They think he will not live to get through.”[47]

Pond in Apperley, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Pond in Apperley, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

William Davis described a different form of family responsibility that kept some of the early members from emigrating: a spouse who was not a member of the Church. When there was not a large concentration of Church members in an area, many young people had a hard time finding someone to marry who shared their faith. William Davis stated that Brother Roberts’s two daughters “both married out of the church which they regret very much.”[48] Some of the individuals who married out of the Church may have been faithful in their hearts, but found it difficult to participate in Church meetings, or to provide opportunities for their children to learn the gospel. Emigration might not have been a possibility.

Because not everyone who might have desired to emigrate was able to do so, we tried to look at other options for examining the faithfulness of the people who stayed in England. Some of the people who could not emigrate had family members who did manage to join the Saints in America. In the instances that FamilySearch.org showed a full pedigree and family group record for converts who remained in England, we could usually trace other family members, often finding that someone in the family had emigrated. This pattern helped us account for the William and Margaret Lane Crook family of Apperley and Deerhurst, Gloucestershire. According to FamilySearch Family Tree, William and Margaret died in England in the 1870s, but three of their adult children emigrated to join the Saints in Utah. At least twelve individuals listed in the database who died in England had spouses, children, or grandchildren who emigrated to Utah or Idaho. Although these records alone do not prove that these twelve people remained active in the Church until they died, their emigrant family members perhaps reflected the faithfulness of those who remained in England.

Deerhurst. Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Deerhurst. Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The situation of Elizabeth Tringham provides a contrasting example. Wilford Woodruff baptized Elizabeth in 1840. Her grandson, Charles Smith, left a diary in which he stated that both his grandfather and grandmother joined the Church in early 1840 and he was baptized in August 1840. He wrote that his grandfather, Lindsey Tringham, left the family in 1841 to go to Nauvoo, but his grandmother stayed in England because she did not want to travel on the sea. After a short time in Nauvoo, Lindsey Tringham became somewhat disillusioned about the Church and returned home to his family. Charles noted that when he decided to emigrate to Nauvoo in 1842, his grandmother “tied up my clothes in a bundle and told me to go and never return.”[49]

Individuals Not Clearly Tracked. Sometimes while searching Family Tree for the converts, we found there was very little information about their lives, and their ordinances all occurred within the last forty years, probably due to the Church extraction or indexing programs. While this finding does not indicate that the early converts were disaffected from the Church in England, it is possible that the descendants of these converts did not remain involved in Church activity and had not provided genealogical data for their ancestors. For example, Jonathan Lucy did not emigrate, but in the British Mission Manuscript History, he is named as the leader of the Colwall Branch through 1847.[50] While he is not named again as the branch leader, there was a Colwall Branch in existence through 1854,[51] so he might have been actively involved in the Church during that time. Because there are no other Church records of the Lucy family, there is no evidence of his continued activity after the branch disbanded. The Lucy family’s records on Family Tree appear to have been extracted from Colwall parish records. Thus, even though Jonathan and his wife might have been faithful throughout their lives, the next generation may not have been active in the Church.

Home of Jonathan Lucy, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Home of Jonathan Lucy, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The Lucys and others may have had difficulty remaining active in the Church if the branch in their village dissolved and they had to travel many miles to attend meetings. The Millennial Star conference reports and the British Mission Manuscript History provided data showing how branches and conferences grew, changed boundaries, and disbanded as time went on.[52] One of the patterns we noticed was that many of the small branches in rural villages were in existence from 1840 until the mid-1850s and were then either dissolved or subsumed into larger branches in bigger towns and cities. Only 10 percent of the branches in the Three Counties listed in the Manuscript History continued beyond 1860. Branch membership probably changed due to new baptisms, emigration, inactivity, or death, so branch boundary changes often reflected the locations of the bulk of the Saints. While these changes may have been important for building a strong base for the Church in larger towns and cities, they could have caused difficulty for people in the small villages who might not have been able or willing to walk several miles to Church every Sunday to join with the Saints in other towns. Those people might not have left the Church in their hearts, but they may have felt that the Church left them.

Because branch boundary changes might have affected the Church activity of many in our databases, we looked at how many of the people died in England before the 1861 census, during the time when the likelihood of having a nearby branch of the Church was higher. Of the 295 people in the journal database not listed on the emigration websites, 26 percent died in England prior to the 1861 census. Similarly, of those in the branch database, 30 percent of those who did not emigrate also died before 1861.[53] The individuals who died earlier than 1861 may have continued activity in the Church until they died since there was a local branch to attend. We consider it likely that some who lived beyond those twenty years without emigrating may not have had the means or opportunity to remain actively involved in the Church because relocated branches were too far away.

William G. Davis’s missionary journal from the 1880s contains examples showing the impact branch boundary changes had on Church activity. As he visited the branches and members of the Church, Davis found individuals who had been members for many years. Davis was welcomed by the Chambers family in Shucknell Hill. They said they had been members of the Church since 1850, “but the branch being broken up about 1855 they had not met with the saints since that time.”[54] Some families listed in the journal database from the 1840s were participating in their local Church branches when Davis met them in the 1880s. For example, Jonathan Davis, who was baptized by Wilford Woodruff on 13 March 1840, was still faithful to the gospel in 1881. William Davis visited with him several times and learned that the family was waiting to hear from friends in Utah who had promised to help them emigrate.[55] Unfortunately, the Jonathan Davis family was still in Bishops Frome, Herefordshire, during the 1891 census and could not be found in emigration records. William Davis also wrote about a few people who were not exemplary members of the Church; for example, he met the president of one of the branches coming home after spending his wages at the “publick house according to the usual custom.”[56]

Those who Fell Away. Not all the converts from the Three Counties in the 1840s were stalwart in their new beliefs. William Williams recorded that in the early days of the Church the Saints “seemed to have forgot there was a Sifting time to come That the Net when it was cast into the Sea gatherd good & bad fishes we were astonished that Some as Soon as Persecuton were offended and would go no more with us I soon began to See why this was and asked the Lord for Strength to keep me faithful to the End That I might be Saved.”[57] Trials and persecution motivated some like Williams to pray for strength to stay the course, but such difficulties led others to leave their newfound faith.

Countryside around Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Countryside around Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

Because the available public records for the databases do not give specific information about each person’s faithfulness to the Church, we relied on anecdotes about some families to enlighten us about their Church activity. Both the Castree and Holley families from Garway Hill had family members who emigrated to Utah, but some of those who stayed behind may not have been strong in their faith. A local history book about Garway Hill, Herefordshire, mentions some of the early Church members who lived in the area, including the Castree and Holley families. This history states that three of John and Anne Cecil Holley’s sons left for Utah in 1856, while the rest of the Holley family stayed in England.[58] Because no Church records are now available for the Garway area, there is no record of whether the Holley family in England remained faithful to the Church in their lifetime. However, the history of Garway Hill provides information that some members of the Castree family had difficulties in remaining true to their faith. Several of the Castrees are described as “colourful,” having been written up in the Hereford Times because of some criminal activity.[59]

When Thomas Steed went back to the Three Counties as a missionary in 1875, he visited Henry Jones, whom he described as an “apostate” living near Malvern Link, Worcestershire. He visited him several times, trying to convince him of the error of his ways, and Thomas finally told Henry that “he was a miserable, unhappy man.” Henry’s daughter corroborated that remark, saying, “Father, you know you are a miserable, unhappy man.” A few days later, Thomas went again see Henry Jones, afterwards writing, “How great his darkness! That man once enjoyed the light of the Holy Spirit, but now denies the power thereof.”[60]

In addition to anecdotal data for individuals, the conference reports published in the Millennial Star can give a perspective on overall faithfulness of the members in the Three Counties. For example, in 1859, the Millennial Star referred to some of the Church members in the Cheltenham, Worcestershire, and Herefordshire Conferences as “dull and sleepy.”[61] The dullness, or lack of interest and enthusiasm, may have come as the members had been in the Church for many years but had not yet joined in emigration. On a more positive note, laudable things must have occurred soon thereafter; later that same year the Star recorded, “Cheltenham Branch, which was the dullest in the Conference, but is now flourishing. . . . The old suspicious spirit is almost defunct.”[62]

The Kitchen, Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

The Kitchen, Garway, Herefordshire. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

While investigating apostasy versus faithfulness in the Three Counties, we found a few sources with information regarding members in the British Isles being cut off (excommunicated) during the early days of the Church. Little information on excommunication is available through the journal database because journals are not official records of the Church. Only a handful of people in that database are listed as “cut off” because their excommunication was specifically mentioned in journals. One example, mentioned earlier, is the Margretts family, whom John Spiers described as apostates acting in opposition to the missionaries.[63] Another example, taken from the journal of James Palmer, mentions that in a January 1841 meeting at the Kitchen (Brother Thomas Arthur’s home) in Garway, Philip Castrey, a member of the Castree family mentioned earlier, was cut off. In spite of his disaffection from the Church, he must have repented because about a year later, Palmer noted that he baptized Philip Castrey. [64]

Unlike the journal database, the branch database, coming from official Church membership records, contains excommunication data for thirty-five individuals. Four of those thirty-five have a rebaptism date listed, and another five people are recorded in the emigration records, signifying that they probably rejoined the Church. The majority of those excommunicated were not mentioned in later Church records, but they could have been rebaptized even though the early records are lacking that information.

Starting in 1847, the Millennial Star conference reports began to record the number of members who had been excommunicated (cut off) since the previous conference. A report of people being cut off in the Three Counties gives us insight into excommunication decisions. At the 29 August 1847 Mars Hill Conference in Herefordshire, the president of the conference “observed that the number cut off might seem great, but he could say with assurance, that there had not been one cut off, or even one suspended, during the last fourteen months that he had been there, that was in good standing when he came; those that had been dealt with were some that had not been known as Saints for years past, and he was glad to see their names erased.”[65] This Church leader apparently thought it was important to remove from the Church records the names of people not participating regularly in meetings.

In 1853, the Millennial Star reported that Church membership numbers for the first half of 1852 were incorrect in many parts of the British Isles because of errors in recording those who had emigrated, been cut off, or died, as they found “many members unaccounted for.”[66] Church leaders at the national level suspected that conferences had been dropping off the names of people who could not be found.[67] This problem evidently continued for several years; in 1859, members were being cut off without the knowledge of the president of the conference,[68] and sometimes without the knowledge of the Church member. In July 1860, a Millennial Star editorial mentioned, “Out of the many thousands who have been cut off from the Church in these lands, a large portion have retained the spirit of the work. Indeed, many of them have not known that they were cut off from the Church until some months afterwards.”[69]

As implied by the statements from British Church leaders in the mid-1800s, some were excommunicated as punishment for not attending meetings regularly with the Saints. Mary Philpotts of Cradley, Herefordshire, received a letter declaring, “The Officers in the Ridgway Cross branch met in Council July 6th . . . and it was declared that you had neglected your Duty according to the covenant you made, in not assembling with the Saints. It was proposed and carried in this Council that you be notified to appear with the Saints on Sunday, July 13th or you must expect to be dealt with according to the law of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”[70] Apparently, Mary Philpotts did not make it to Church that day; according to a history of Cradley, she returned to the Church of England.

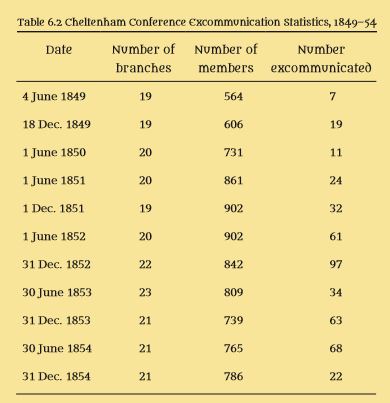

Table 6.2 shows the report of excommunications for the Cheltenham Conference during the years 1849 to 1854, the only years for which the Millennial Star reported these statistics for each conference in the British Mission. The table shows that a number of excommunications occurred in that conference during these years with similarities to those of Mary Philpotts and those reported in the 1860 editorial in the Millennial Star.

In conclusion, without further study and comparison of all other areas of the Church and more complete records from the Three Counties, Wilford Woodruff’s statement that fewer converts apostatized from the Three Counties than from any other area may never be verified. The incompleteness of the records for the Three Counties suggests that records of Church membership in other areas might be somewhat lacking as well. Thus, such a study would be extremely difficult.

Another difficulty we encountered in this study is that the databases and the public records we used provided very little information about those who left the Church. In the branch database, results are limited to what was available about the Church members in the Bran Green and Frogmarsh area. While this study cannot give an accurate number of the early converts to the Church in the Three Counties who actually remained actively involved in the Church, it does show that nearly one-half of the members in our databases emigrated to join the Saints in America. Many of those who stayed in England may have remained faithful, at least while there were active branches in their area. Further research using additional branch and conference records might provide more accurate rates of activity and apostasy during the mid-nineteenth century in England.

Notes

[1] Wilford Woodruff, in Journal of Discourses, 15:345.

[2] “Conference Minutes: Worcestershire Conference” Millennial Star 10 no. 11 (12 June 1848): 168.

[3] “Statistical Report of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the British Isles,” Millennial Star 15 no. 31 (30 July 1853): 510.

[4] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1:490 (11 August 1840).

[5] Mormon Migration, https://

[6] Edward Phillips, “Biographical Sketches of Edward and Hannah Simmonds Phillips, 1889, 1926, 1949,” 1, MS 11215, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[7] “Emigration,” Millennial Star 1, no. 10 (February 1841): 263.

[8] The finding that no one emigrated from the branch before 1849 provides evidence that in all likelihood the branch records were kept in earnest starting in the mid to late 1840s. If the records had started when the branch was first created in 1840, they would have included the names of individuals from the journal database who left England in the early 1840s.

[9] Sarah Ann Oakey Ludlum, “Her Journey West,” in Treasures of Pioneer History, comp. Kate B. Carter (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1956), 5:257–58. Sarah’s description does not mention where her sister Rhoda Rebecca died, but FamilySearch Family Tree provides a death date of 9 November 1856, with the place being Emigration Canyon in the mountains east of Salt Lake City. According to the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel website, the Willie handcart company arrived in Salt Lake City on 9 November 1856, the same day as Rhoda’s death.

[10] Jane Ann Fowler Sparks, Jane Ann’s Memoirs, comp. Marsha Passey (Montpelier, ID: M. Passey, 2004), 6.

[11] Mary Ann Weston Maughan, “The Journal of Mary Ann Weston Maughan,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 2:357.

[12] Maughan, “Journal,” 358.

[13] Emily Hodgetts Lowder, “Emily Hodgetts Lowder—103 Years,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 7:425; emphasis in original.

[14] “Disgraceful Elopement,” The Times (London, England), Friday, 4 April 1856, 11.

[15] “Emily Hodgetts Lowder—103 Years,” 425.

[16] “Emily Hodgetts Lowder—103 Years,” 426; William B. Hodgetts Company 1856, found on https://

[17] Francis George Wall, “Francis George Wall—Pioneer of 1863,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 7:364.

[18] Mary Field Garner, “Mary Field Garner autobiographical sketch, ca. 1940,” 2, MS 10472, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[19] Sarah Davis Carter, “She Came in 1853,” in Our Pioneer Heritage, 12:227.

[20] Carter, “She Came in 1853,” 227–8.

[21] Phillips, “Biographical Sketch,” 2.

[22] Job Taylor Smith, “Job Smith Autobiography, circa 1902,” 5, MS 4809, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[23] Smith, “Autobiography,” 18, 21, 27.

[24] “The Nauvoo Brass Band,” Contributor 1, no. 6 (March 1880), 135–36.

[25] Thomas Steed, “The Life of Thomas Steed From His Own Diary, 1826–1910,” 8–10, BX 8670.1 .St32, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT (parentheses in original). Also online at https://

[26] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 10.

[27] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 11–17.

[28] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 22.

[29] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 25.

[30] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 33, 36.

[31] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 3.

[32] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 5.

[33] Phillips, “Biographical Sketch,” 2.

[34] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 8.

[35] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 9–10.

[36] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 13.

[37] Garner, “Autobiographical Sketch,” 13.

[38] William Clayton, “William Clayton Diary, 1840 January–1842 February,” 29 October 1840, MS 2843, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[39] 1850 census, Hancock County, Illinois, “United States Census, 1850,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://

[40] John Spiers, “John Spiers Reminiscences and Journal, 1840–77,” 30–31 (29 October 1841), MS 1725, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[41] “Obituary: John Fido,” Deseret News, 7 September 1881, 512.

[42] Smith, “Autobiography,” 21.

[43] Carter, “She Came in 1853,” 227. Although Sarah Davis Carter recalled in her history that the Davis family traveled in 1853, the passenger list for the Windermere on Mormon Migration, shows that the family traveled in 1854, leaving Liverpool 22 February 1854.

[44] Samuel Eames, “Samuel Eames correspondence 1861,” MS 9490 Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 3. Transcription is by Jay G. Burrup.

[45] William George Davis, “William G. Davis Diaries, 1880–1882,” 31 (4 December 1880), MS 1689, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[46] Davis, “Diaries,” 50 (4 February 1881).

[47] Davis, “Diaries,” 42 (10 January 1881).

[48] Davis, “Diaries,” 51 (7 February 1881).

[49] Charles Nephi Smith, “Diary and Reflections of Charles ‘Nephi’ Smith, son of Thomas and Mary Smith,” 2, https://

[50] “First Division of Mars Hill Conference,” Millennial Star 9 no. 6 (15 March 1847): 83.

[51] “Home Intelligence: Herefordshire Conference,” Millennial Star 16, no. 42 (21 October 1854): 665.

[52] For more information on Church units in the Three Counties, see the table in the appendix.

[53] Over 100 people could not be identified on the 1851 or 1861 censuses for whom we have no death date or place, so we cannot be sure if they died, or if they had moved to another county.

[54] Davis, “diaries,” 63 (18 March 1881).

[55] Davis, “diaries,” 33 (13 December 1880), 102 (9 May 1881).

[56] Davis, “diaries,” 31, (5 December 1880).

[57] William Williams, “William Williams reminiscence, 1850,” 9, MS 9132, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Spelling and punctuation are in the original.

[58] Joan and Brian Thomas, Garway Hill Through the Ages (Almeley, Herefordshire: Logaston Press, 2007), 127–29. FamilySearch Family Tree shows that the temple ordinance dates for the Holley and Castree family members who settled in Utah took place during their lifetime, while those for the people who stayed in England were not completed until after their deaths. That finding, however, may only reflect the fact that there was no temple in England at the time.

[59] Joan and Brian Thomas, Garway Hill Through the Ages, 134.

[60] Steed, “Life of Thomas Steed,” 33–34.

[61] “Minutes of the Special Council,” Millennial Star 21, no. 6 (5 February 1859): 96.

[62] “Correspondence: Cheltenham Pastorate,” Millennial Star 21, no. 24 (24 June 1859): 384–85, italics in original.

[63] Spiers, “reminiscences,” 30–31 (29 October 1841).

[64] James Palmer, “James Palmer Reminiscences, ca. 1884–98,” 20, 60, MS 1752, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[65] “Conference Minutes: Mars Hill,” Millennial Star 10 no. 3 (4 February 1848): 37.

[66] “Half-yearly Statistical Reports, and Records,” Millennial Star 15 no. 5 (29 January 1853): 73–74.

[67] “Half-yearly Statistical Reports, and Records,” Millennial Star 15, no. 5 (29 January 1853): 74.

[68] “Minutes of the Special Conference,” Millennial Star 21, no. 8 (19 February 1859): 130.

[69] “Editorial,” Millennial Star 22, no. 28 (14 July 1860): 441.

[70] Wynnell M. Hunt, Cradley: A Village History (Trowbridge, England: W. M. Hunt & Cradley Village Hall Management Committee, 2004), 19.