Gathering in His Name, Remotely

Scott C. Esplin

SCOTT C. ESPLIN (scott_esplin@byu.edu) IS THE PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR OF THE BYU RELIGIOUS STUDIES CENTER.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem during Easter’s Holy Fire ceremony in 2017. Photograph by Scott C. Esplin.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem during Easter’s Holy Fire ceremony in 2017. Photograph by Scott C. Esplin.

Gathering together for religious study and worship is one of the oldest forms of human interaction. For millennia, the faithful of numerous religious traditions have sacrificed to worship in shrines, sanctuaries, and temples around the globe. Scholars estimate as many as 300 million people annually embark on some form of pilgrimage. These include countless millions who flock to Middle Eastern cities like Mecca and Jerusalem, India’s Bodh Gaya and Varanasi, Japan’s Shikoku Island, and Europe’s Lourdes or Rome. Hundreds of millions of others gather on a regular basis in local churches, synagogues, and sanctuaries to commune with God.

Pilgrims praying at the Great Mosque of Mecca in 2003. Photograph by Ali Mansuri, Wikimedia Commons.

Pilgrims praying at the Great Mosque of Mecca in 2003. Photograph by Ali Mansuri, Wikimedia Commons.

Members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints share in this desire to gather together to talk of and rejoice in Christ (see 2 Nephi 25:26). Modern revelation indicates “it is expedient that the church meet together often to partake of bread and wine in the remembrance of the Lord Jesus,” mirroring a Book of Mormon pattern (Doctrine and Covenants 20:75; see also Moroni 6:6). In addition to gathering for regular religious services, members also frequently assemble in other sacred spaces. Each year, hundreds of thousands pray in Palmyra’s Sacred Grove, sing “The Spirit of God” in the Kirtland Temple, or walk the quiet streets of Nauvoo. Youth groups around the world don bonnets and bandannas to pull handcarts in pioneer trek reenactments or gather around campfires for testimony meetings. Most importantly, hundreds of thousands worship regularly in sacred temples, performing essential ordinances for themselves and others.

In 2020, this religious rhythm of the world, as well as that of the Church, has been upended by a global pandemic. The Hajj to Mecca, one of the five pillars of Islam and something that many faithful Muslims plan a lifetime to experience, was discouraged by Saudi Arabian officials worried about a gathering that would assemble an estimated two million people in close proximity. For the first time in centuries, sites in Jerusalem sacred to the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ were closed for the Palm Sunday, Good Friday, and Easter celebrations that highlight the Christian calendar. During the same season, Jewish groups dramatically scaled back their Passover celebrations around the world. For Latter-day Saints, weekly sacrament meetings have been canceled, temple worship restricted, pageants postponed, and pioneer treks rescheduled. At the April 2020 general conference that was, itself, transformed into a broadcast-only event, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland noted, “Even as we speak, we are waging an ‘all hands on deck’ war with COVID-19, a solemn reminder that a virus 1,000 times smaller than a grain of sand can bring entire populations and global economies to their knees.”[1]

Statue of Brigham Young wearing a mask during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Nate Edwards/

Statue of Brigham Young wearing a mask during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Nate Edwards/

As everywhere else in the Church, Religious Education at Brigham Young University has been impacted by this upheaval. In March, classes pivoted to remote instruction, with students encouraged to return to their homes, where possible, while faculty scrambled to transform classes tailored around high levels of interaction into online gatherings. A university task force was quickly formed with representatives from the various colleges, including Religious Education, who counseled together about the impact on the campus community. Professor Anthony Sweat, one of the representatives from Religious Education, observed, “It was fascinating to watch how quickly decisions needed to be made, how vastly information and perspectives shifted within hours and days (from a temporary shutdown to a more long-term approach), and how capably and flexibly the administration, faculty, and students all responded to suddenly shifting the entire thirty-thousand-plus students at the university to remote instruction within a week. It really was an organizational, technological, and educational feat that is unprecedented in our history.” Remote instruction continued throughout spring and summer terms, and students and faculty learned new ways to continue to “instruct and edify each other” (Doctrine and Covenants 43:8).

Devotional with Elder Jack N. Gerard in the Marriott Center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Nate Edwards/

Devotional with Elder Jack N. Gerard in the Marriott Center during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Nate Edwards/

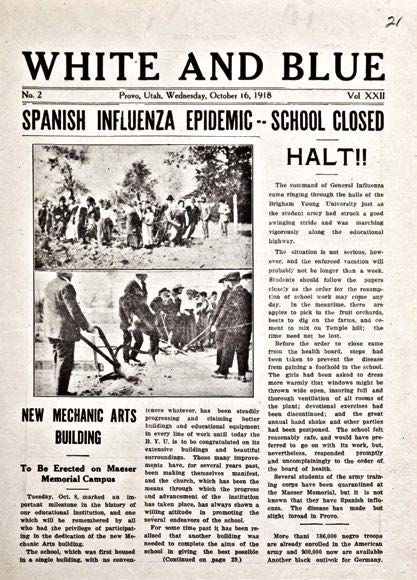

A Pattern in Our History

Scientists, scholars, and social commentators have drawn comparisons between the COVID-19 pandemic and earlier contagions that ravaged the world, including the 1918 flu epidemic. On Wednesday, October 16, 1918, the campus newspaper White and Blue boldly heralded, “SPANISH INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC—SCHOOL CLOSED. HALT!!” The university community hoped for a swift end to the closure, with the paper declaring, “The situation is not serious, however, and the enforced vacation will probably not be longer than a week. Students should follow the papers closely as the order for resumption of school work may come any day.” While noting that several students were quarantined in the Maeser Memorial Building, the paper concluded, “The disease has made but slight inroad in Provo.”[2]

BYU’s White and Blue student newspaper announcing the closure of campus due to the 1918 flu epidemic. Public domain, courtesy University Archives.

BYU’s White and Blue student newspaper announcing the closure of campus due to the 1918 flu epidemic. Public domain, courtesy University Archives.

Church officials in Salt Lake City did not share in the campus optimism. On October 10, 1918, Elder James E. Talmage (1862–1933) of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles wrote in his journal, “Yesterday an order was promulgated by the State Board of Health, effective this morning, directing the suspension of all public gatherings owing to the continued spread of the malady known as the Spanish influenza. The Salt Lake Temple was closed at noon today, and instructions were issued that all the Temples be closed and all Church meetings be suspended. This is probably the first time in the history of the Church that such radical and general action has had to be taken.”[3] Six days later, Elder Talmage continued, “The influenza epidemic is claiming an increasing toll of lives all over the country. Surely a desolating scourge and sickness is sweeping the land. The mandate of the State Board of Health regarding public gatherings in Utah is rigidly enforced. House parties, public funerals, except in the open air, and wedding receptions are specifically forbidden. The exigency seems to fully warrant this drastic action.”[4]

American Red Cross community center kitchen for influenza patients in Salt Lake City, ca. 1914–1919. Courtesy Library of Congress.

American Red Cross community center kitchen for influenza patients in Salt Lake City, ca. 1914–1919. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Elder Talmage’s concern regarding the gravity of the 1918 flu epidemic proved prophetic. Significant Church events, including the November 1918 funeral of Church President Joseph F. Smith, were held privately, and the April 1919 general conference was postponed until June. While exact figures are difficult to determine, somewhere between twenty and one hundred million people died globally from the pandemic between 1918 and 1920, including nearly seven hundred thousand Americans.[5] In Provo, hundreds of people, including students, perished.

Lessons Learned

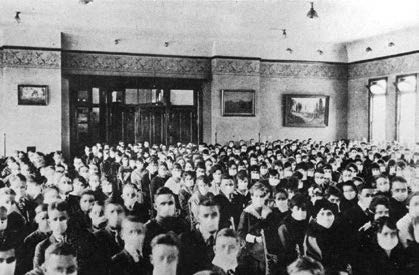

When classes resumed in January 1919, students returned to a changed world. Activities were curtailed and masks were common. But light from heaven burst forth during the challenging time as well. Just as the flu started to take hold, President Joseph F. Smith received a revelation regarding the redemption of the dead. Known today as Doctrine and Covenants section 138, it describes Christ’s ministry in the world of spirits and the saving work that occurs there as the gospel message is proclaimed to all. In a season of despair, learning prevailed.

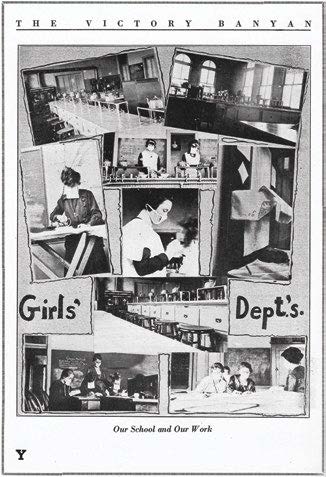

BYU students and staff wearing masks during the 1918–19 flu epidemic, featured in BYU’s annual student yearbook, The Victory Banyan, published in 1919.

BYU students and staff wearing masks during the 1918–19 flu epidemic, featured in BYU’s annual student yearbook, The Victory Banyan, published in 1919.

We are learning lessons in Religious Education from the Covid-19 pandemic as well, though they do not rise to the level of President Smith’s revelation. Professor Sweat summarized, “Pedagogically, I believe that the shift to remote education, long term, will cause us as religious educators to reevaluate why we physically gather students together to learn. It was assumed (and used to be) to disseminate information. But internet technology has decentralized information. Lectures can be given live online or prerecorded and downloaded. Student discussions can happen via the discussion board tool found in many learning management systems. Students can have powerful spiritual experiences with truth through carefully guided, independent assignments.”

Professor Tyler Griffin, another religious educator on the university task force, likewise observed, “This shift has forced teachers, students, administrators, and support staff to all rethink what is absolutely essential in an educational setting. Many things that were previously seen as nonnegotiable requirements in our courses have now become nearly impossible to implement. This has opened many conversations about how we can adapt and shift our focus to those things that we can do online.”

President Joseph F. Smith with his wife Julina, ca. 1916. Courtesy Church History Library.

President Joseph F. Smith with his wife Julina, ca. 1916. Courtesy Church History Library.

Remote instruction is not without its drawbacks. Professor Sweat continues, “It is usually not as rewarding as a teacher to teach remotely. I miss the physical ‘connection’ with the students and the class—reading the body language and vibe of the class and simultaneously being edified together.” But a change in classroom delivery can also have positive impacts. Professor Griffin noted how it is reshaping student interaction. “While many would think that moving students out of a classroom into an online environment would result in less engagement with the content, I have found the opposite to be true. It is far easier for a student to disengage during a classroom lecture than it is online. I am asking them to respond to questions using the chat box and putting them in breakout rooms to discuss principles and applications. These activities invite everyone to stay engaged and focused more than normal because they will all engage with more questions rather than sitting back and waiting for a few vocal students to do all the participating.”

BYU students assembled in College Hall during the 1918 flu epidemic. Public domain, courtesy University Archives.

BYU students assembled in College Hall during the 1918 flu epidemic. Public domain, courtesy University Archives.

Students likewise adjusted to the remote instruction. Though challenges emerged, several praised the newfound flexibility while others noted the learning that occurred. “The accessibility . . . was really nice,” one student remarked. “I was able to get all of the work done and learn so much on my own time.” Another added, “I was shocked how much I was able to learn. I loved learning on my own time.”

Hope from Heaven

Professor Brent L. Top teaching a Religious Education graduate class on Zoom during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Richard Crookston.

Professor Brent L. Top teaching a Religious Education graduate class on Zoom during the Covid-19 pandemic. Photograph by Richard Crookston.

In spite of the challenges presented by the pandemic, we remain optimistic that good can result. Professor Griffin emphasized that remote instruction does not reduce spiritual power. “The Holy Ghost is not limited by the use of technology or the spread of distance. When students hear the gospel as taught from the scriptures and words of the living prophets, the Spirit testifies of truth and changes lives. The students are more than willing and able to adapt to the new learning environment online. They have proved to be more open to these changes than many of the faculty who feel nervous to have their content and lecture material put into a digital form.”

Indeed, there is hope on the horizon. Professor Sweat concluded, “I am fundamentally rethinking why we gather, why it’s necessary, what are its benefits, and how to maximize and create more purposeful educational gathering when we return to face-to-face instruction. I need to do more research and exploring, but a blended, mastery-learning approach seems to me to be the wave of the future, and this quarantine has accelerated the speed of that oncoming wave in my own future teaching.”

As the pandemic started to grip Church and campus life in dramatic ways, President Russell M. Nelson shared his hope: “These unique challenges will pass in due time. I remain optimistic for the future. I know the great and marvelous blessings that God has in store for those who love Him and serve Him. I see evidence of His hand in this holy work in so many ways.”[6] He later added, “We rejoice in the peace that radiates from the Lord Jesus Christ. It will continue to fill us with hope and joy. Our Heavenly Father and His Beloved Son love us, are aware of us, and will bless each of us. I love you, dear brothers and sisters, and assure you that wonderful days are ahead.”[7]

Notes

[1] Jeffrey R. Holland, “A Perfect Brightness of Hope,” Ensign, May 2020, 82.

[2] “SPANISH INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC—SCHOOL CLOSED. HALT!!,” White and Blue, October 16, 1918, 1. For additional information about BYU during the 1918 flu epidemic, see the recent BYU Magazine feature by Michael R. Walker, “Lessons from 1918,” in the spring 2020 issue.

[3] James E. Talmage, October 10, 1918, James E. Talmage journal 22, MSS 229 box 5, folder 9, in James Edward Talmage Collection, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[4] James E. Talmage diary, October 16, 1918.

[5] Leonard J. Arrington, “The Influenza Epidemic of 1918–19 in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 58, no. 2 (Spring 1990): 165–82.

[6] Russell M. Nelson, https://

[7] Russell M. Nelson, https://