A Celebration of Interfaith Activity

Robert L. Millet

ROBERT L. MILLET IS PROFESSOR EMERITUS OF ANCIENT SCRIPTURE AT BYU.

Twenty years ago, in May 2000, a very significant meeting took place in a conference room of the N. Eldon Tanner Building on the Brigham Young University campus. A group of Latter-day Saint Religious Education faculty members met for the first time with six Evangelical Christian scholars to begin what came to be known as the “Mormon-Evangelical Dialogue.” The evangelicals included their leader, Richard J. Mouw (president of Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena at the time), Craig Blomberg (Denver Seminary), Pastor Gregory Johnson (president of Standing Together), Craig Hazen (Biola University), and Carl Mosser (a PhD candidate). Latter-day Saint participants included Stephen Robinson, Andrew Skinner, David Paulsen (Philosophy, BYU), Roger Keller, and Robert Millet, leader of the BYU group.[1]

It was decided in that first gathering that our purpose was not apologetic—we were not there to defend our own faith. Nor was it evangelistic—conversion of the “other” was not the reason for coming together. We determined that our overarching purpose was to build bridges, enhance understanding, correct misunderstanding and misperception, and establish meaningful friendships. The dialogue has been much more than a conversation. We have visited key historical sites, eaten and socialized, sung hymns and prayed, mourned together over the passing of members of our group, and shared ideas, books, and articles throughout the years. There has developed a sweet brother- and sisterhood, a kindness in disagreement, a respect for opposing views, and a feeling of responsibility toward those not of our faith—a responsibility to represent their beliefs and practices accurately to members of our own faith. We as Latter-day Saints hate to be misrepresented; why, then, would we ever want to misrepresent the beliefs of persons of other faiths? No one has compromised or diluted his or her own theological convictions, but everyone has sought to demonstrate the kind of “convicted civility”[2] that ought to characterize a mature exchange of ideas among a body of believers in the Prince of Peace. No dialogue of this type is worth its salt unless the participants gradually begin to realize that there is much to be learned from men and women who believe differently than we do.

Group of BYU Religious Education faculty members with Evangelical Christian scholars on the steps of the John and Elsa Johnson home in Hiram, Ohio in July 2017. All photos courtesy of Robert Millet.

Group of BYU Religious Education faculty members with Evangelical Christian scholars on the steps of the John and Elsa Johnson home in Hiram, Ohio in July 2017. All photos courtesy of Robert Millet.

True dialogue is tough sledding, hard work. In my own life it has entailed a tremendous amount of reading of Christian history, Christian theology, and, more particularly, evangelical thought. We determined early on that we could not very well enter into another’s world and way of thinking unless we immersed ourselves in that person’s literature. This we did before each dialogue. Doing so is especially difficult when it comes out of one’s own hide, that is, when it must be done above and beyond everything else one is required to do—teaching, researching, publishing, and carrying out citizenship responsibilities. It takes a significant investment of time, energy, and money.

It soon became clear that far more critical to success in this dialogue than intellectual acumen was a nondefensive, clearheaded, thick-skinned, persistent but kind and pleasant personality. Those steeped in apologetics, whether Latter-day Saint or evangelical, face an especial hurdle, an uphill battle, in this kind of dialogue. We agreed early on, for example, that we would not take the time to address every polemic against Joseph Smith or the Book of Mormon, any more than a Christian-Muslim dialogue would spend appreciable time evaluating proofs of whether Muhammad actually entertained the angel Gabriel. Furthermore, and this is much more difficult, we agreed as a larger team to a rather high standard of loyalty—that we would not say anything privately about the other guys that we would not say in their presence in our dialogue setting.

The first dialogue was as much an effort to test the waters as to engage a specific topic. The evangelicals asked that we all read or reread Anglican scholar John Stott’s classic work, Basic Christianity, and some of the BYU contingent recommended that we read a good introduction to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. When it came time to discuss Basic Christianity, we had a rather revealing experience. Richard Mouw asked, “Well, what concerns or questions do you have about Stott’s book?” There was a long and somewhat uncomfortable silence. Richard followed up: “Isn’t there anything you have to say? Did we all read the book?” Everyone nodded affirmatively that they had indeed read it, but no one seemed to have any questions. Finally, one of the BYU team members responded: “Stott is essentially writing of New Testament Christianity, with which we have no quarrel. He does not wander into the creedal formulations that came from Nicaea, Constantinople, or Chalcedon. We agree with his assessment of Jesus Christ and his gospel as presented in the New Testament. Great little book.”

Gathered in Salt Lake City are Gregory Johnson, Elder Robert Wood, Gerald McDermott, Elder Jeffrey Holland, Richard Mouw, Spencer Fluhman, Robert Millet, Grant Wacker, and Grant Underwood.

Gathered in Salt Lake City are Gregory Johnson, Elder Robert Wood, Gerald McDermott, Elder Jeffrey Holland, Richard Mouw, Spencer Fluhman, Robert Millet, Grant Wacker, and Grant Underwood.

After a few years of dialogue, Richard Mouw suggested that we not meet next time in Provo but rather in Nauvoo, Illinois. We spent several wonderful, faith-filled days in the “City of Joseph.” Feelings were tender on both sides, and tears were shed by many at the Carthage Jail, as well as during our brief contemplative walk down Parley Street to the Mississippi River, where the Saints in February of 1846 began their exodus to the Great Basin. Our meeting one evening in the upstairs room of the Red Brick Store was especially interesting, as we discussed the organization of the Relief Society, the vital place of temples in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the first temple endowment was administered there), and Joseph Smith’s conferral of all the keys of the kingdom on the Twelve Apostles. On the night before we were to leave Nauvoo to return home, we held our final meeting in the Seventy’s Hall. We sang hymns, and Richard Mouw spoke on the topic “What I would love to see take place within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the next twenty-five years.” I then spoke on “What I would love to see take place within evangelicalism in the next twenty-five years.”

Two years later we met in Palmyra, New York, and once again focused much of our attention on historical sites and sacred events in Palmyra and Fayette. Our two hours in the Sacred Grove was absolutely priceless, as we discussed the religious world of 1820, as well as the doctrinal significance of the Prophet Joseph’s first vision. One of the last Church historical sites that the entire group visited was Kirtland, Ohio, where our discussion was on spiritual gifts. It shocked some of our evangelical friends to learn that Latter-day Saints were speaking in tongues some seventy years before the famous Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles, California, during the early years of the twentieth century. We each had reaffirmed what we had come to know quite well in Nauvoo—that there is in fact something very real called “sacred space.”

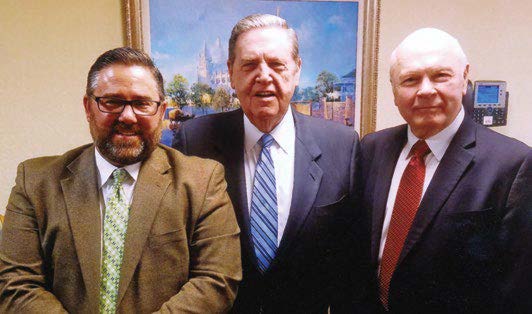

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, who offered much encouragement for interfaith efforts, meets here with Pastor Gregory Johnson and Robert Millet.

Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, who offered much encouragement for interfaith efforts, meets here with Pastor Gregory Johnson and Robert Millet.

Other doctrinal topics discussed through the years included the nature and effects of the Fall, how salvation comes, the canon of scripture, revelation, authority, and the nature of God and the Godhead/

Our time together has resulted in mental stretching, jettisoning incorrect notions about the other, and soul-searching. Several participants have remarked that even in some of our most intense conversations they felt a special spirit in our dialogue, a kind of Superintending Presence attending our poor efforts. We felt that the Lord approved of what we were striving to do. On a number of occasions as we have ended the two-to-three-day dialogue, a scriptural passage has come to mind. The Savior taught that “where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20). To borrow Oliver Cowdery’s words, “these were days never to be forgotten” (Joseph Smith—History, 1:71 footnote). In fact, they were days that have proved to be life changing.

“An Evening of Friendship” will be held in the spring of 2021. It will represent a formal conclusion to the dialogue and a celebration of twenty years of study, conversation, discovery, bridge building, and treasured friendship. The celebration will be open to the public.

Notes

[1] Over the years the faces of the dialogue group changed, with the exception of a few on each side who remained involved to the dialogue’s conclusion. Evangelicals who later joined the dialogue include David Neff (at the time editor-in-chief of Christianity Today), James Bradley (Fuller Seminary), Doug McConnell (Fuller Seminary), Bill Heersink (independent scholar), Donald Hagner (Fuller Seminary), Dennis Okholm (Azusa Pacific University), Cory Willson (Calvin Seminary), Stephanie Bliese (Garrett Theological Seminary), Gerald McDermott (Beeson Divinity School), Anthea Butler (Penn State), Christopher Hall (Northern Seminary in Pennsylvania), and John Turner (George Mason University). Latter-day Saints who were involved for a number of years include Camille Fronk Olson (Ancient Scripture, BYU), Paul Peterson (Church History and Doctrine, BYU), Rachel Cope (Church History and Doctrine, BYU), Shon Hopkin (Ancient Scripture, BYU), Jana Riess (independent scholar), Richard Bennett (Church History and Doctrine, BYU), Phil Barlow (Utah State University), Grant Underwood (History, BYU), Spencer Fluhman (History, BYU), J. B. Haws (Church History and Doctrine, BYU), Brian Birch (Philosophy, Utah Valley University).

[2] This is a term used by Richard Mouw in his book Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World, rev. ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010). American religious historian Martin Marty once commented that there are many people in this world who are convicted (devoted to their faith), and there are many people who are civil (who deal kindly and respectfully with people). But there are very few who are both convicted and civil.