Q&A

Conversations with Mary Jane Woodger and Andrew C. Skinner

Latter-day Prophets: A Conversation with Mary Jane Woodger

Interview by Jonathon R. Owen

Mary Jane Woodger (maryjane_woodger@byu.edu) is a professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU.

Jonathon R. Owen (jonathon.owen@gmail.com) is a graduate student in linguistics at BYU.

Owen: You have cited David O. McKay as a great influence in your life. Which teachings of his have shaped who you are?

Woodger: There is a lot about David O. McKay that has definitely shaped who I am. He was the subject of my dissertation, and I was really pleased to find that his attitudes towards education were much the same as mine. I just read an article written by someone else that wanted a critique of it, and one of the things they were getting after President McKay about was being too idealistic. That is one of the things that I cherish about him—he put an ideal forward and said, here’s the ideal, and I’m not going to apologize. That’s the way it can be, and that’s what you work towards. That has definitely affected my life as a teacher, to say, here’s the ideal, and that’s what we’re going to work for.

And of course, President McKay was in such a key position. What he taught had so much to do with marriage and the family. Yet during his era, the real attack on the family had not hit yet. What he did for that generation was to prepare them to raise the next generation when the attack would come. It is an incredible testimony to me that the Lord knows exactly who he needs to have in place, and he does it every time.

Owen: I understand that you are researching George Albert Smith and the trials he faced in his life. What are some of the insights you have gained as you have looked into his life?

Woodger: He is interesting because when we look at the Brethren, we do not think they ever have big problems. We think that they just handle everything, that they are spiritual giants. The main thing I have discovered with George Albert Smith is that he suffered a nervous breakdown. He had an emotional collapse that was precipitated by great physical problems. The thing I find interesting about him is how he faced those problems and what brought him out of it, and it was definitely prayer. He got to the point where he did not think that he could go on. In fact, he was asking the Lord to release him. As he submitted to the Lord and then asked his wife for help also, that is when the great turning point came in his life.

The other thing that I like about George Albert Smith is that he was known for being the most pleasant, kind, Christlike individual, and no one knew except his close associates what he was really going through. But he knew his limits. There were times when he just went to bed. He fulfilled his positions, he fulfilled his responsibilities, but he knew his limits. He was only the prophet for six years, and he is one that we kind of skip over. There are so many Smiths that he gets lost in the mix. But he was brilliant and had great characteristics, great love and great kindness, and he came in right between Germany surrendering and Japan surrendering in World War II and bound up those wounds that people were suffering from after World War II. He did it in an amazing way, demonstrating great Christlike love.

Owen: What do you hope your students will have learned by the time they leave your class?

Woodger: My main desire for my students is to see the great hand of the Lord in the history of the Church and also in the lives of our current General Authorities. I hope they will transfer that to their own lives and realize that the Lord is directing them also. Of course, my greatest desire is for them to receive that witness that these men are who we say they are. I hope that as they leave they will have a great desire to continue to study their lives and their teachings. I hope especially in my living prophets class that the general conference we study that particular semester will be like none other, and that thereafter, conference will be a great hallmark in their lives.

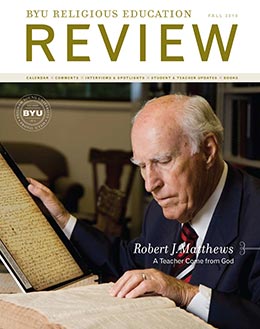

The King James Bible: A Conversation with Andrew C. Skinner

Interview by Laurie R. Mildenhall

Andrew C. Skinner (andrew_skinner@byu.edu) is one of two Richard L. Evans professors of Religious Understanding at BYU.

Laurie R. Mildenhall (lauriemildenhall@gmail.com) is a junior in graphic design at BYU.

Q: Next year is the four hundredth anniversary of the publication of the King James Version of the Bible. Do you have any insights on the sacrifices of those who made it possible to have the scripture in English?

A: The story of the English Bible is filled with stories of sacrifice and service to humanity and a real desire to spread the message of Christianity throughout the world. The story begins with John Wycliffe, who was born in the English countryside in the early 1300s. Because he showed significant potential, he went to Oxford to complete his education. While at Oxford, he began to have a significant change of mind about the doctrines of his own confession, Roman Catholicism. The more he studied, the more he came to believe that the centerpiece of Christianity, the root and foundation of all Christian doctrine and practice, ought to be the Bible, yet there were no English Bibles in existence. So he made it his twofold purpose in life first to get people to see the errors of the practices of clergymen in the Roman Catholic Church, and second, to do something about the lack of the Bible in English. The two went hand in hand, and his work influenced generations of reformers after him. Wycliffe died in 1384, but his work influenced later reformers, including a Bohemian reformer by the name of Jan Hus, who in turn influenced Martin Luther, the leader of Protestant Reformation.

Many ideas of the Protestant Reformation were rooted in the ideas of John Wycliffe. In fact, Wycliffe was the one who started talking in terms of sola fide, Latin for “by faith alone,” and of course that theme was picked up by other reformers, particularly Martin Luther. In the year 1377, Wycliffe began to launch a series of attacks against the Roman Catholic Church, not because he was antireligious but because he felt that Christianity had slipped from its moorings, that it had gotten away from biblical Christianity, and that it had gotten away from the original texts of the New Testament. He made it his life’s work to try to bring Christianity back to its pristine purity and to get rid of all the traditions and trappings, the pomp and circumstance. Even such an important doctrinal concept in Roman Catholicism as transubstantiation was not found in the scriptures; therefore he believed it was not valid. He said the idea of a pope was not found in the scriptures, so the pope is unnecessary. They did not need intermediaries or a priest to tell people what they should believe and how they should live their lives. They needed people who could read the scriptures.

So the English Bible really was born as a result of Wycliffe’s attempt to bring Christianity back to its pristine nature as described in the New Testament. He gathered a group of followers known as the Lollards, and when he finished overseeing the translation of the Latin Bible into fourteenth-century English, a sort of army of scripture readers went out into the English countryside carrying the new Bible. The people of the communities that welcomed the Lollards were sometimes not even able to read, but they could understand. And most of them that could read did not have enough money to buy the scriptures. Scriptures were very expensive because it took, on average, ten months to produce one copy of the English Bible. People could rent a copy of the Bible for a few hours in a day, and the going price for two or three hours was an entire load of hay. So these people made huge sacrifices to read a copy or to have it read to them. The sacrifices that Wycliffe himself went through were incredible. Of course, his work did not endear him to the officials of the Roman Catholic Church. Four decades after he was buried, the leadership ordered that his remains be dug up, dragged to a field near the River Swift, chained to a stake, and his bones burned to ash. The ashes were smashed into the ground then gathered up and thrown into the river to be taken into the ocean.

Later a man named William Tyndale came along, and he is the father of the English Bible as we know it. The King James Version of the Bible is based largely on the work of Tyndale. In fact, between 70 and 90 percent of everything we find in the pages of our King James Bible was the work of Tyndale. Tyndale was born in 1492. He was one of the great heroes and great geniuses of the Western tradition. He was treated horribly. He was arrested, put in a dungeon, and ultimately burned at the stake because of his commitment to give the English Bible to people who needed to have the word of God in a language that they could understand. He, like Wycliffe, believed that if you have a Bible in your own language, you do not need intermediaries, you do not need priests, you simply need the word of God. With the word of God, you can understand exactly what Christ intended for everybody to understand. You can feel the promptings of the Holy Spirit. Of course, that idea put in jeopardy the Roman Catholic leadership, and that is one of the reasons why Tyndale was burned at the stake. The history of the reformers, starting with John Wycliffe and continuing with Jan Hus, Martin Luther, and William Tyndale, is really a story of people who put their whole lives in jeopardy to produce for us what we have now in the pages of the King James Version. So when I read the King James Bible, I am not only reading the theology and the doctrine but also thinking about the sacrifices of all of these men and women who sometimes paid with their lives. I am seeing the sacrifices of my fellow Christians, four, five, or six hundred years ago who would pay a load of hay just to have a Bible in their hands for two hours. This is an incredible story, and one that goes hand in hand with the Restoration of the gospel. I like to tell my students that in the King James Version and the previous iterations of the English Bible, we have God working to give us a Bible fit for the Restoration. And the Joseph Smith Translation improves the King James Version. But the Joseph Smith Translation is founded on the King James Version, which is founded on Tyndale’s Bible, which is founded on the work of Wycliffe.