The Woman at the Veil: The History and Symbolic Merit of One of the Salt Lake Temple’s Most Unique Symbols

Alonzo L. Gaskill and Seth G. Soha

Alonzo L. Gaskill and Seth G. Soha, “The Woman at the Veil: The History and Symbolic Merit of One of the Salt Lake Temple's Most Unique Symbols,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 91–111.

Alonzo L. Gaskill was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

Seth Soha was a graduate of Brigham Young University and an independent scholar when this article was written.

Known as the "Angel of Peace," a copy of this statue is placed atop the veil in the Salt Lake Temple. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

Known as the "Angel of Peace," a copy of this statue is placed atop the veil in the Salt Lake Temple. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

Brother Cowan has dedicated much of his life and career to a study of the house of the Lord. He has taught literally thousands of students in his LDS Temples course—myself (Alonzo) being one of them. Most Fridays, Richard and his wife, Dawn, can be found in the Provo Temple, engaging in the very rites he has reverently taught about for so many years. He is unquestionably a temple-loving disciple, faithfully serving the Lord, and when we think of Richard Cowan, this promise made by Jesus comes to mind: “Him that overcometh will I make a pillar in the temple of my God, and he shall go no more out” (Revelation 3:12). God bless you, Richard, for your teachings and faithful example.

The Salt Lake Temple has been called “the most important building of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”[1] By all accounts, it is our most unique, eclectic, and architecturally grand temple. If, as they say, the Prophet Joseph was “a prophet’s prophet,”[2] then the Salt Lake Temple is certainly a “temple’s temple.” Of all of our buildings, it is the most universally recognized by those outside of our faith, and it is the quintessential symbol of temples among practicing Latter-day Saints.

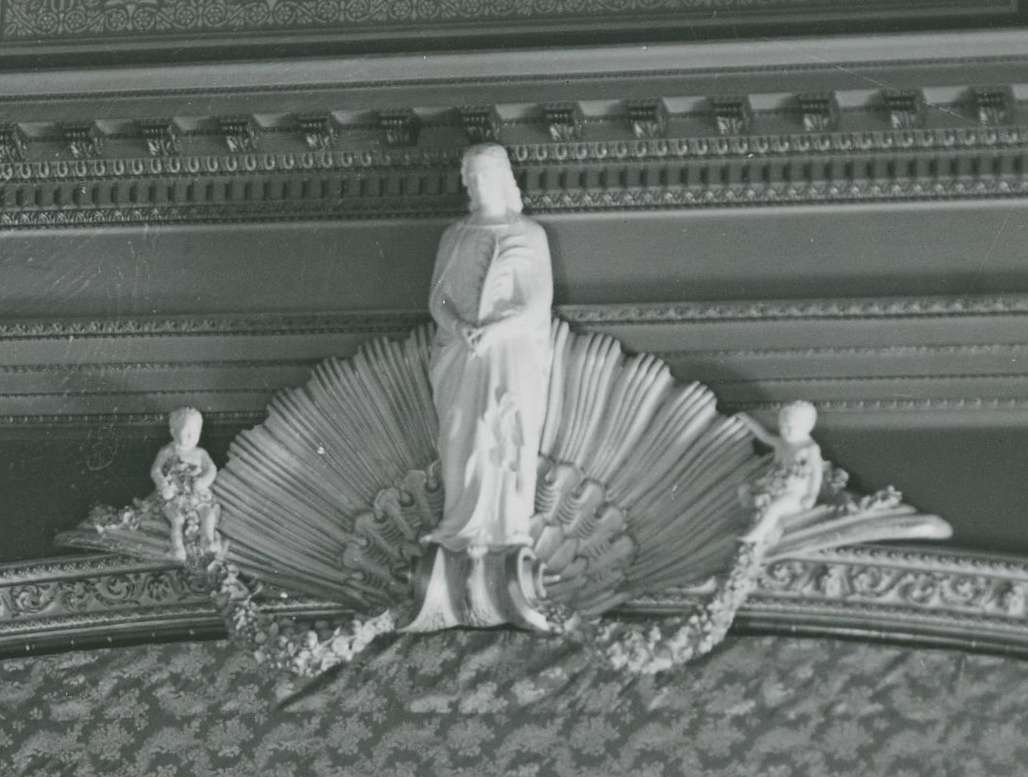

Salt Lake Temple celestial room with the statue above the veil. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

Salt Lake Temple celestial room with the statue above the veil. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

So much of the symbolism of this nineteenth-century gift to God is unique: from the exterior walls and doorknobs to the interior murals and stained glass. No temple of the Restoration, before or since, has utilized such distinctive symbols as teaching tools for its patrons.

One of those matchless symbols is found on the west wall, above the veil in the celestial room: an imposing six-foot figure, clasping a branch and flanked by two cherubs.

The statue above the veil of the Salt Lake Temple. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

The statue above the veil of the Salt Lake Temple. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

The origin and meaning of this conspicuously placed statue has caused no small amount of speculation. Rumors run rampant, and yet documentation is difficult to come by. Claims as to the intended identity of the unidentified woman over the veil include the Virgin Mary (supposedly given as a gift to the Latter-day Saints by the Roman Catholic Church),[3] the Roman goddess Venus or the Greek goddess Aphrodite,[4] Heavenly Mother,[5] and even an effeminate Jesus.[6] There is no end to the conjecture. However, as we shall show, none of these suppositions agree with what we know historically about the origins of this statue, let alone with the doctrines of the Church.

Historical Origins

In scouring archives, books, articles, and the like for information regarding this statue and its origins, one quickly realizes how little has been formally written on the subject. While there is plenty of folklore and misinformation available, an accurate recitation of the statue’s genesis has been elusive. Among the many theories as to the statue’s identity and origins is this: “The statue was purchased out of a catalogue, as were many of the fixtures of the Salt Lake Temple. It doesn’t represent anyone or anything. It is just an interesting figure common to the era.”[7] While this explanation may serve to squelch the sizable amount of speculation which swirls around the statue’s identity, it misrepresents the historical facts regarding its origins.

The head architect of the Salt Lake Temple was Truman O. Angell Sr. (1810–87). He served in that capacity for thirty-four of the temple’s forty years of construction.[8] Angell’s successor was Joseph Don Carlos Young (1855–1938), son of President Brigham Young.

Joseph Don Carlos Young was the successor to Truman O. Angell as the head architect of the Salt Lake Temple.

Joseph Don Carlos Young was the successor to Truman O. Angell as the head architect of the Salt Lake Temple.

Don Carlos had been involved in the details of the temple prior to Angell’s death, shouldering some of the burden during Angell’s later years when his health prohibited him from fully functioning.

Within a few months of the death of Truman O. Angell, Joseph Don Carlos Young was appointed to be his successor. By the spring of 1888, he was already revising Angell’s plans for the interior of the building. It was appropriate that one of Brigham Young’s sons would be responsible for the completion of the temple. Don Carlos’s appointment marked a new era in which the Church would have academically trained architects available. Though he received a degree in engineering from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy, New York, in 1879, he had always been interested in architecture: “As the temple architect . . . Don Carlos’ major contribution was redesigning Truman Angell Jr.’s[9] plans for the interior of the Temple while maintaining his predecessor’s basic layout and movement. . . . The result was a more aesthetically pleasing and unified design.”[10]

Joseph Don Carlos Young’s handiwork is evident not only in the layout of the interior but also in the original furnishings. Indeed, he is the individual responsible for the presence of “the woman at the veil,” and his acquisition of the statue came through a rather fortuitous turn of events.[11] His grandson explained:

Grandfather wanted to go to school in the east, along with his brother Feramorz (and others); and they asked their father if they could go. Well, one of Brigham’s counselors had spoken in Conference recently and said that our young people should stay at home and shouldn’t travel. They should stay here [in Utah] and build up the Kingdom. Well that was contrary to what [Joseph Don Carlos Young] wanted to do.

So Brigham extracted a promise from [Don Carlos]: if he would let him go, when [Don Carlos] returned he would go to BYU and teach for three years. So [Don Carlos] went to Rensselaer Polytechnic, in Troy, New York. . . . They didn’t have an architecture department. It was engineering [back then]. . . .

[He] attended Rensselaer Polytechnic [from 1875 to 1879]. He came home [briefly] in ’76. He didn’t come home for his father’s funeral in ’77. He had asked his father permission to come home the summer of ’77. And Brigham wrote him back and said “You and Feramorz could best utilize your time if you would go to Boston and put yourselves in the hands of Dudley Buck”—who was the greatest organist in the United States [at that time]. He said Brother [George] Careless [the conductor of the Tabernacle Choir] was not well and they would perhaps need [Don Carlos’] help when he came home. [Brigham was a] very practical man. . . . And he said, “If you spend your vacation in the way that I have intimated, it will be the best for you. But be sure [that you] do not study as to injure your health.”

So, that summer—rather than coming home—[Don Carlos] went to Boston. Dudley Buck was in residence in New York City, so [upon learning this] he and Feramorz went to New York City. He had an interview with Dudley Buck [who] told him he did not have enough of the rudiments of the piano to start an organ career.

But while [Don Carlos] was in New York (in ’77) they went down to the Italian district—down by the Battery [on the southern tip of Manhattan Island]—and [he] noticed these young boys sitting on the curb, carving Carrera marble. And he took a liking to this one [statue—the one that would eventually be placed above the veil of the temple] because it was nearly completed. And so he purchased it [along with the two busts of the cherubs]; not knowing what he would use it for—he just loved it![12]

Had Young not briefly pursued the possibility of learning the organ, he would not have been in New York City on the occasion of the carving of the statue and would therefore not have acquired it.

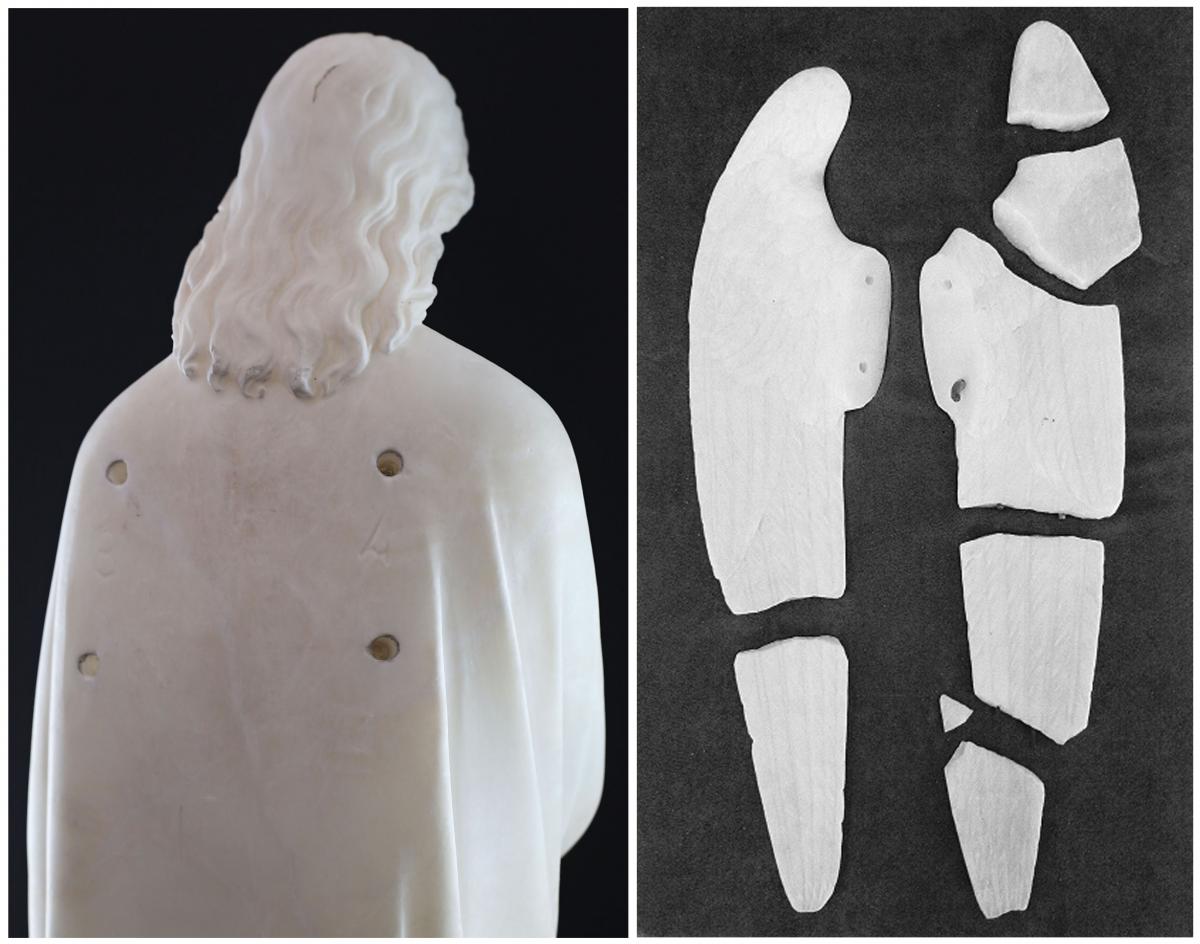

The original three statues acquired by Joseph Don Carlos Young in New York. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

The original three statues acquired by Joseph Don Carlos Young in New York. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

Only a few years after his acquisition, Don Carlos found himself employed in helping to build the temple. Just over a decade after the purchase, he was the head architect. This facilitated the woman at the veil’s placement in the temple. According to Don Carlos’s son, “this angel and cherubs were taken to the temple by father as a model for the angel and cherubs that are over this arch coming into the Celestial Room.”[13] From the eighteen-inch original, a “Utah sculptor” carved the six-foot-high statue one sees today above the veil.[14] While we can’t say for sure, speculation has been that the large-scale statue of the woman and cherubs were the artistry of the non-LDS sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin.[15] Dallin not only sculpted the statue of Moroni atop the Salt Lake Temple, but he did so out of plaster[16]—the same medium used to sculpt the cherubs and woman in the celestial room. There is a remarkable resemblance between Dallin’s known works and the cherubs of the Salt Lake Temple. In addition, it is likely that Dallin carved the statue because he and Don Carlos knew each other,[17] and Young may have selected him for the creation of this work, just as President Woodruff had selected him for the sculpting of the statue of Moroni.

Unlike what we see in the temple today, the original statue had wings and was named (apparently by the young boy who carved it) “the Angel of Peace.” In his personal notes about the statue, Joseph Don Carlos Young penned this:

About the middle of Fall one cold night as I was sitting with my feet enjoying the warmth of an open grate and my mind drowsily meditating on the power of the priesthood on earth as vested in a Prophet Seer and Revelator and the invisible power or influence that seems to accompany the Church of Christ as manifested everywhere, my eyes involuntarily raised to the mantel and my mind centered on a statue of the Angel of Peace by ( ) the original of which is in the

chathedcathedral of ( ).[18] Those who have seen it or copies remember it represents the old Christian idea of heavenly beings and is presented with a beautiful pair of wings carved in the most exquisite manner. Many times I have sat and admired this beautiful work but now something seemed to displease me. I thought what if Joseph, who had seen an angel should come here if he would admire this! or if Brigham or John would allow such as this to stand in a niche of our temple. The more my mind ran in this direction I felt impelled to remove the wings. Now I saw a smile and expression that I never saw before and I can now allow this . . . to be placedthere againwhere the sculptor had placed them again.[19]

Out of concern that the prophets—Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, or John Taylor—might be bothered by the wings on the original statue (and any replication of them on the copy made for the temple), Don Carlos removed them from the back of the original statue and felt that the improvement made the statue suitable to be placed in the house of the Lord.

The back of the original eighteen-inch statue with four holes visible, where the original wings (pictured above) were once attached. (Photo by Greta Montejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

The back of the original eighteen-inch statue with four holes visible, where the original wings (pictured above) were once attached. (Photo by Greta Montejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

The reverse of the eighteen-inch statue now has four small holes where the wings were initially attached. The original marble figure and the six-foot plaster copy in the temple are, to this day, wingless, in accordance with Don Carlos’s impressions that fall evening.

In its early days, the statue in the Salt Lake Temple was a pure white (like the marble original from which it was copied). Over time, however, portions were painted: starting with the palm branch and garland. Eventually the entire statue was colorized. All of this was done after the death of Joseph Don Carlos Young. One of the Church’s curators noted: “The current color scheme in the room was mostly done during the 1960s renovation by Edward Anderson. There were some slight color changes in about 1974 then again in 1982. Both of those were Emil Fetzer[20] managed projects.”[21] Dave Horne, one of the painters involved in the remodel and the painting of the statue, indicated that it was in the 1960s that the majority of the colorization took place. He, along with Arnie Roneir and Alfred Nabrotski, changed the skin tone on the cherubs and woman, whereas previously only the palm branch and garland had been colorized.[22] As noted, none of this coloration was done during the life of Don Carlos, and there is reason to believe that he would not have been thrilled by the changes.[23]

Symbolic Merit

Based on the history, it is apparent that the statue is not the Virgin Mary, Venus, Aphrodite, Heavenly Mother, or Jesus. It would be misrepresentative to say that we know for certain what Joseph Don Carlos Young saw as the statue’s ultimate symbolic meaning. Nor can we say that we know why its location over the veil was, for him, preferential to any other location in the temple. Don Carlos left us few clues. He did refer to the statue as “the Angel of Peace”—but it is unclear whether this was his name for the statue, or the name given it by the young boy in New York who carved it.[24] The only other piece of symbolic information Young left us was his statement that it symbolizes “heavenly beings” (in the plural).[25] Thus what follows is but an examination of standard religious and scriptural symbolism, and how that relates to “the woman at the veil.”

Keying off Joseph Don Carlos Young’s statement that the statue is representative of “heavenly beings,” we turn to John the Revelator’s description of the bride of Christ. John records in the twelfth chapter of the book of Revelation, “And there appeared a great wonder in heaven; a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars” (Revelation 12:1).[26] The “woman” is a standard scriptural symbol for the Church.[27] The fact that she is “clothed with the sun” represents her godly or celestial nature. Thus the woman described in the book of Revelation represents members of the Church who are keeping the commandments and are living pious lives.[28] She is a representation of all those who will receive exaltation in the celestial kingdom, thus becoming “heavenly beings.”[29] The “crown” the woman (in John’s vision) wears is significant. The Greek makes it clear that it is not a metal crown, like those worn by kings or rulers. Rather, it is a laurel-wreath crown, symbolic of victory.[30] Thus she symbolizes those in the Church who overcome the world and are victorious against Satan.[31] Consequently, John describes those who were exalted through the blood of the Lamb as being “clothed with white robes, and [having] palms in their hands,” crying “with a loud voice, saying, Salvation to our God which sitteth upon the throne, and unto the Lamb” (Revelation 7:9–10). What John sees in the woman is all Saints who have faithfully endured and have thereby been exalted. The woman’s white robe reminds us of her state of purity. The palm branch she holds is symbolic of her victory over Satan and the world! That being said, it seems “the woman at the veil” in the Salt Lake Temple is an ideal symbol for the bride of Christ—male and female—exalted in the celestial kingdom of God.[32] Clothed in a white robe we understand her to have successfully utilized the Atonement of Christ to receive purity through his blood. In her hands we see a palm branch, symbolic of her victory in the great test of mortality.

Some have suggested that the woman at the veil is holding an olive branch. However, a closer inspection suggests that it is instead a palm branch. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

Some have suggested that the woman at the veil is holding an olive branch. However, a closer inspection suggests that it is instead a palm branch. (Photo by Greta Motiejunaite, courtesy of Richard W. Young.)

Drawings of olive branch (left) and palm branch (right). (Drawings by J Keaton Gaskill.)

Drawings of olive branch (left) and palm branch (right). (Drawings by J Keaton Gaskill.)

Joseph Don Carlos Young’s explanation of the statue as a symbol of “heavenly beings” is perfectly in alignment with John’s description of the bride of Christ, who symbolizes all Saints who become “heavenly” through their faith in the merits of Christ and through obedience to his word and will.

The cherubs who flank “the woman at the veil” are also instructive for temple patrons. President Brigham Young remarked: “Your endowment is, to receive all those ordinances in the House of the Lord, which are necessary for you, after you have departed this life, to enable you to walk back to the presence of the Father, passing the angels who stand as sentinels, being enabled to give them the key words, the signs and tokens, pertaining to the Holy Priesthood, and gain your eternal exaltation in spite of earth and hell.”[33] The cherubs flanking the bride, placed at the threshold or entrance to the celestial room, appropriately mirror those “angels who stand as sentinels.” As one source notes, they are “guardians of the sacred and of the threshold.”[34] Their presence there suggests that all those on the celestial side of the veil have symbolically achieved their exaltation and are now worthy to dwell in God’s holy presence. The garland which they drape in front of the now exalted bride of Christ suggests her newfound access to the fruit of the tree of life, constituting every blessing available to, and to be enjoyed by, those who have received their exaltation.[35] As the Lord has promised the faithful, “all that my Father hath shall be given” unto them (D&C 84:38).

As for the fan-like figure behind the woman,[36] and upon which the cherubs perch, we simply remind the reader that this has traditionally been associated with the spiritual strength which comes from heeding the promptings of the Lord’s Spirit. It represents the power had by the Spirit directed over Satan and his influence. It is suggestive of the dignity which comes to those who are deified and reside for eternity in the presence of their God.[37]

Conclusion

The uniqueness of the Salt Lake Temple is a significant part of its appeal. While the ordinances offered therein are the same as those performed in other temples of the Church, Salt Lake’s symbolic uniqueness makes it a “teaching Temple” in ways that other temples of the Restoration are not. One small component of that is the “woman at the veil.”

Truly, one of the beauties of a symbol—whether scriptural, architectural, or otherwise—is that it can teach us many things, contingent upon our level of understanding, spiritual advancement, and attention to detail. As one commentator rightly pointed out:

Symbols are the language of feeling, and as such it is not expected that everyone will perceive them in the same way. Like a beautifully cut diamond, they catch the light and then reflect its splendor in a variety of ways. As viewed at different times and from different positions, what is reflected will differ, yet the diamond and the light remain the same. Thus symbols, like words, gain richness in their variety of meanings and purposes, which range from revealing to concealing great gospel truths.[38]

What a blessing it is to be able to be taught from on high through a never-ending well of symbolic insights and ordinances. Truly, symbols are the language of God. He employed them throughout the scriptures, and he utilizes them everywhere in the temple. To understand them is to find meaning. To misunderstand them is to court confusion. As we seek to learn the standard symbols of the scriptures and the Restoration, we find God teaching us about our place in his sacred plan. If, on the other hand, we neglect to educate ourselves in this divine language, we are more prone to confusion and erroneous ideas.

For all of the folklore which surrounds this wonderful statue, Young’s “woman at the veil” is one of the Salt Lake Temple’s most unique and edifying symbols. And while many have interpreted its symbolic purpose in unique ways, with Don Carlos we say it is, indeed, an “Angel of Peace” in that it can remind us—the bride of Christ—of the Lord’s promise to all those who work righteousness: “even peace in this world, and eternal life in the world to come” (D&C 59:23).[39]

Notes

[1] C. Mark Hamilton, The Salt Lake Temple: A Monument to a People, 5th ed. (Salt Lake City: University Services Corporation, 1983), 8.

[2] Robert L. Millet, “Joseph Smith among the Prophets,” Ensign, June 1994, 19; Robert L. Millet, “Joseph Smith among the Prophets,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1993), 15.

[3] As an example, one Latter-day Saint blogger explained: “In 1992 (or there about), I went to the Salt Lake temple. While waiting for the rest of my party to come into the Celestial Room, I turned around the way I had come so that I could see them when they came. Above the veil was a statue that I recognized as the Virgin Mary from my days growing up in New Mexico. I asked one of the temple workers about it. He said that when the temple was dedicated, the Catholic church gave the church the statue. The brethren thought that the most appropriate place for the statue was in the Celestial Room.” Comment posted by “Floyd the Wonderdog,” May 31, 2008, on “Mary and Judith: Images of Women in the Salt Lake Temple, 1915,” By Common Consent, May 30, 2008, bycommonconsent.com/

[4] See, for example, Val Brinkerhoff, The Day Star—Reading Sacred Architecture, 3rd ed., 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: Digital Legends Press, 2012), 2:139. See also http://

[5] See, for example, Brinkerhoff, Day Star, 2:139, 175n86; http://

[6] Though not a common theory, a few have proposed that the statue was intended to be a depiction of the Savior. See, for example, http://

[7] This was the claim of several we talked to at the Church Archives in Salt Lake City.

[8] Truman started his work on the temple on January 22, 1853, and continued working on that edifice until his death on October 16, 1887. There was a period from 1861 until 1867 in which he was not able to work on the project due to severe illness. See Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 50.

[9] Truman Angell Jr., the son of Truman Angell Sr., assisted his father and Joseph Don Carlos Young on the Salt Lake Temple starting in 1877—though much of the time (between 1877 and 1884) he was consumed with work on the Logan Temple, managing the construction of that edifice. The junior Angell was a draftsman and served in that capacity on the Salt Lake Temple. See Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 58.

[10] Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 56–57. In the last year of the temple’s construction, when they were pushing to get the interior done by the planned dedication in April, Joseph Don Carlos Young became ill. He “offered to resign, if doing so would hasten the completion of the work. President Woodruff refused and insisted that Young accomplish as much as he could and let others help.” See Hamilton, Salt Lake Temple, 56–57.

[11] George Q. Cannon’s journal, currently housed in the Church Archives, suggests that there was discussion about placing Alfred W. Lambourne’s painting of Adam-Ondi-Ahman over the veil (where the statue of the woman currently stands). Apparently not everyone involved in the decision-making process agreed on this, but ultimately Don Carlos’s desire won the day, and the Lambourne painting was placed elsewhere in the temple.

[12] Richard Wright Young, interview by authors, October 9, 2012, Salt Lake City. See also George Cannon Young, George C. Young Oral History (unpublished manuscript: 1980), 13–14.

[13] Young, Oral History, 13.

[14] See Eugene Young, “Inside the New Mormon Temple,” Harper’s Weekly, May 27, 1893, 510. It appears that the temple statue was most likely carved in 1892 (or possibly in early 1893), during the last year of the temple’s construction.

[15] Dallin, a Utah-born non-Mormon, initially turned down the invitation of President Wilford Woodruff to make the statue of the angel Moroni for the Salt Lake Temple. He told President Woodruff “that he was not a Mormon and ‘didn’t believe in angels.’” It was his opinion that “someone of greater spiritual capacity should be given the opportunity.” With urging from his mother and the prophet, Dallin eventually “accepted the commission and began a study of Latter-day Saint scriptures and doctrine in an effort to truly interpret Moroni’s character.” Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, Every Stone a Sermon (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1992), 48.

[16] Young, interview, October 9, 2012.

[17] We know that Dallin and Young met on July 21, 1891, to discuss the statue of the angel Moroni and that it was not the only statue he created for the Church. See Matthew O. Richardson, “Voices of Warning: Ironies in the Life of Cyrus E. Dallin,” in Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The New England States, ed. Donald Q. Cannon, Arnold K. Garr, and Bruce A. Van Orden (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2004), 211.

[18] Don Carlos was trying to recall the name of the boy in New York who carved the original statue and the location of a similar statue that the boy had told him he had modeled his after, but to no avail. The blanks and strikeouts in this quote are in Young’s original notebook.

[19] Joseph Don Carlos Young, Private Notebook (no date; no pagination). This notebook is in the possession of Richard Wright Young, grandson of Joseph Don Carlos Young. The scans of the originals are in possession of the authors.

[20] In 1965 Emil B. Fetzer was called by President David O. McKay to serve as LDS Church architect, a position he held for twenty-one years. He designed more than twenty temples around the world, including the Provo, original Ogden, and Jordan River temples, as well as the Mexico City, Freiberg Germany, and Tokyo Japan Temples. Fetzer also managed the remodel of a number of existing temples, including the Salt Lake Temple.

[21] Emily Utt, historic site curator for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, personal correspondence, October 16, 2012.

[22] Conversation with Dave Horne, October 16, 2012. Horne was a subcontractor who worked on the Salt Lake Temple almost daily for seventeen years. Horne’s brother, Dan (also a contractor), indicated that according to his recollection, Arnie Roneir was the one who actually painted the woman; and that took place in the early 1960s. Conversation with Dan Horne, October 24, 2012.

[23] Don Carlos’s son, George Cannon Young, noted in his oral history: “Recently this marble statue replica has had color put on it—on the lips and other parts (flesh color)—which horrifies me. I can’t imagine taking that replica of a marble statue and making [a] human out of it. To me that is almost sacrilegious and following the tradition of the sectarian world.” George added a family concern: “The time will come . . . that in the modernization of our temple buildings that this [statue] will be discarded.” Young, Oral History (1980), 13, 14.

[24] The fact that Don Carlos refers to it as “the Angel of Peace by . . . ” seems imply that the title was that of the sculptor, not Young. See Young, Private Notebook.

[25] See Young, Private Notebook.

[26] The passage goes on to speak of the “woman” being in “travail,” or labor. While some Roman Catholic commentators have taken this to mean that the woman must be Mary and the “baby” Jesus, LDS commentators have interpreted the “child” born to the woman as “the coming forth of the New Israel, or the New Jerusalem.” The baby is not Jesus, but rather “the political kingdom of God whose laws will come forth from Zion.” Richard D. Draper, Opening the Seven Seals: The Visions of John the Revelator (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1991), 130. See also Jay A. Parry and Donald W. Parry, Understanding the Book of Revelation (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 148, 152.

[27] See Draper, Opening the Seven Seals, 129; Parry and Parry, Understanding the Book of Revelation, 151; Bruce R. McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987–88), 3:516; Mick Smith, The Book of Revelation: Plain, Pure, and Simple (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1998), 118; D. Kelly Ogden and Andrew Skinner, Verse by Verse: Acts Through Revelation (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1998), 333; and Leon Morris, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries: Revelation, rev. ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999), 152.

[28] Parry and Parry, Understanding the Book of Revelation, 151; McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 3:516; Smith, Book of Revelation, 119.

[29] Just as the sun is a symbol for things celestial, the moon reminds us of things which are terrestrial. The moon has no light of its own, but rather merely reflects the light of the sun. Thus John utilizes the image of the moon as a symbol for terrestrial churches, or religions that only reflect some truth (revealed through the true Church)—but they are not the source of any of that truth themselves. It suggests that the religions symbolized by the moon are both less than the celestial woman and her truths and also that they are, to some degree, in subjection to her. One text put it this way: “It may suggest that those of the Church who attain a celestial glory will have stewardship and ascendancy over those who attain a lesser glory.” Parry and Parry, Understanding the Book of Revelation, 151. She can raise men to a celestial level, because she is celestial herself. These other faiths—although valuable in making the world a better place and making lives more joyful and spiritual—can only raise men to a terrestrial level (as they have not God’s authority, valid ordinances, keys, etc.). See McConkie, Doctrinal New Testament Commentary, 3:516.

[30] See Draper, Opening the Seven Seals, 129; Gerhard Friedrich, ed., Theological Dictionary of the New Testament, 10 vols. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1983), 7:620, s.v. “The Games.”

[31] The “12 stars” on the head of the woman/

[32] Eugene Young was the grandson of President Brigham Young (through his oldest boy, Joseph Angell Young). Eugene’s mother, who left the Church when Eugene was four years of age, reared him as a non-Mormon. However, because of his connections to the deceased prophet, and because he had an uncle that (in 1893) was serving in the Quorum of the Twelve, President Woodruff allowed Eugene to tour the interior of the Salt Lake Temple the night before it was dedicated. See Eugene Young, “The Mormon Temple—A Letter To A Friend,” The Independent, May 18, 1893, 669. After touring the soon-to-be-dedicated edifice, Young wrote an article in Harper’s Weekly in which he discussed the various aspects of the interior and his general impressions of the temple. Though at times rather antagonistic in his public comments about the Church, in his “Inside the New Mormon Temple” (1893), Young seems rather touched by the building and his experience within. For example, in describing the celestial room, he notes: “If human art can present an idea of heaven, it must be presented in this part of the building, for an air of rest and comfort pervades the very atmosphere” (p. 510). Similarly, in his “Letter to a Friend” he penned this of the celestial room: “The only expression that I can find which will express my ideas of this room is, it is truly heavenly. To attempt to describe it would be folly; for there is nothing with which I can compare it; it is entirely original.” Young, “The Mormon Temple—A Letter to a Friend,” 669. Regarding the statue of “the woman at the veil,” he wrote: “Over the arch [or veil] at the west end of the [celestial] room is a figure of the Virgin in white.” Young, “Inside the New Mormon Temple,” 510. Some have taken his comment about the “Virgin in white” to suggest that the statue was intended to be a representation of the Virgin Mary. It may well be that Young assumed that to be the case. He does not say that someone giving the tour told him this, but he does state rather matter-of-factly that that is what she represents. It is possible that he assumed this on his own, and it is also possible that someone else on the tour erroneously told him this. In addition, it is possible that someone explained to him that the statue represented the 144,000 who, in scripture, are referred to as “virgins” (Revelation 14:4), and he simply assumed that the reference was to the Virgin Mary instead of those who have made their calling and election sure. We have no way of telling for sure. But we should be cautious about putting too much credence in Eugene Young’s comment, as (1) he was not a member of the Church and, therefore, may not have understood the lack of Mariology in Mormonism, (2) he gives no hint of where he developed the opinion that the statue represented the Virgin Mary, and (3) his claim contradicts what Don Carlos Young tells us about the statue—and, after all, Don Carlos is the person who placed the statue over the veil.

[33] Brigham Young, The Complete Discourses of Brigham Young, comp. Richard S. Van Wagoner, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: The Smith-Pettit Foundation, 2009), 2:646.

[34] See Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, 34.

[35] From Lehi’s vision of the tree of life we read: “And it came to pass that I beheld a tree, whose fruit was desirable to make one happy. And it came to pass that I did go forth and partake of the fruit thereof; and I beheld that it was most sweet, above all that I ever before tasted. Yea, and I beheld that the fruit thereof was white, to exceed all the whiteness that I had ever seen. And as I partook of the fruit thereof it filled my soul with exceedingly great joy; wherefore, I began to be desirous that my family should partake of it also; for I knew that it was desirable above all other fruit.” (1 Nephi 8:10–12). One commentator on these verses noted: “In his sermon to the outcast Zoramites (Alma 32–33), Alma identified fruit as the reward of a process. . . . Descriptive of the bounteous blessings of Christ’s atonement, the fruit is most precious, sweet, white, and filling, leaving a disciple to no more hunger or thirst (Alma 32:42).” Camille Fronk, “Fruit,” in Dennis L. Largey, ed., Book of Mormon Reference Companion (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 277. Elsewhere we are informed: “The fruit of the tree of life . . . ultimately is eternal life (1 Ne. 15:36; D&C 14:7).” Donald W. Parry and Jay A. Parry, Symbols & Shadows: Unlocking a Deeper Understanding of the Atonement (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2009), 156. Elder Holland explained: “Christ is the seed, the tree, and the fruit of eternal life.” Jeffrey R. Holland, Christ and the New Covenant (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1997), 169.

[36] This is sometimes erroneously assumed to be a seashell, largely because some wrongly associate the statue with Venus. While it is true that the fluted shell is strongly associated with the goddess Venus in antiquity and in art, we know that the shell, from which she is customarily depicted as emerging, is a standard symbol for fertility or reproduction. [See Jack Tresidder, Symbols and Their Meanings (London: Duncan Baird, 2000), 13. See also Fontana, Secret Language of Symbols, 88; and Hall, Dictionary of Subjects and Symbols in Art, 280.] Again, it would be uncharacteristic for the presiding Brethren to employ such a symbol in the temple. Upon closer examination, one realizes that the design behind the woman is not a fluted shell. It may be nothing more than a classic design or perhaps a fan. Notice, for example, how the two extreme edges of the design, upon which the cherubs are perched, go out—unlike a shell (but like some feathered fans). Additionally, the bottom center of the design (just behind the woman’s calves and feet) has slats in it, like a feather hand fan, but unlike a shell. Thus the artistic representation is certainly not a shell. Again, while it may be nothing more than an aesthetically pleasing design, it may also be intended to represent a fan. From a symbolic perspective, fans stand for celestial things. J. E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, 2nd ed. (New York: Philosophical Library, 1971), 101, s.v. “Fan.” See also Steven Olderr, Symbolism: A Comprehensive Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1986), 47. They represent the Spirit and thus power. See Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, 64. See also G. A. Gaskell, Dictionary of All Scriptures and Myths (New York: Julian Press, 1960), 266. They symbolize that which “wards off evil forces.” See Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, 65. See also George Woolliscroft Rhead, History of the Fan (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1910), 22, 88. They represent the dignity of the one who possesses the device; thus being appropriately placed in the celestial room of the temple. See Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, 64. See also The Herder Symbol Dictionary: Symbols from Art, Archaeology, Mythology, Literature, and Religion, trans. Boris Matthews (Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications, 1986), 73, s.v. “Fan”; and F. L. Cross, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 2nd ed., ed. F. L. Cross and E. A. Livingstone (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 502, s.v. “Fan.” They are frequently associated with life—or, in this case, eternal life. Frederick Thomas Elworthy, The Evil Eye: An Account of This Ancient & Widespread Superstition (London: John Murray, 1895), 176–77. See also Harold Bayley, The Lost Language of Symbolism, 2 vols. (New York: Citadel Press, 1990), 2:162. As one source notes, “The feathers” of a fan “stress the association with . . . celestial symbolism as a whole.” Cirlot, Dictionary of Symbols, 101. Though we cannot be dogmatic about what the design behind the woman was intended to convey, we can say with a high degree of certainty that it is not a shell, and that the woman is not the pagan goddess Venus.

[37] See Cooper, Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols, 64–65; Cirlot, Dictionary of Symbols, 101.

[38] Joseph Fielding McConkie, Gospel Symbolism (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1992), ix.

[39] Nephi equated exaltation (or eternal life) with the receipt of peace (see 1 Nephi 14:7).