Why the “Mormon Olympics” Didn’t Happen

J. B. Haws

J. B. Haws, “Why the “Mormon Olympics” Didn’t Happen,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 365–87.

J. B. Haws was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

Legendary Brigham Young University football coach LaVell Edwards carrying the Olympic torch when the torch relay made its way through Provo, Utah, on February 5, 2002. (Photo by Jaren Wilkey, courtesy of BYU Photo.)

Legendary Brigham Young University football coach LaVell Edwards carrying the Olympic torch when the torch relay made its way through Provo, Utah, on February 5, 2002. (Photo by Jaren Wilkey, courtesy of BYU Photo.)

Richard Cowan is a marvel to me—a man who gives new meaning to the word “indomitable.” His scholarship on so many facets of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Mormon history has been foundational for other researchers, and his work in BYU classrooms over the past half-century has affected the lives of literally tens of thousands of students—and I was one of those students. But I’m most grateful for the lessons he teaches just by being who he is. Early-morning walks to work, team-teaching a class, Mexican food lunches—these are some unforgettable moments with an unforgettable mentor.

Lane Beattie became the state Olympic officer for Utah in 2000 when he retired from the Utah State Senate. His office was flooded with interview requests from journalists from all over the globe who wanted to get a handle on this place where the 2002 Olympics would soon be held. One question always stood out to Beattie: “Can a person get a drink in Utah?”[1] In some ways, that question was code for a larger concern. What inquiring minds really seemed to be asking was, “Will the LDS Church dominate the Salt Lake Winter Games? Will the vaunted Olympic experience be dampened by some stultifying, heavy-handed religion? Basically, will the world even enjoy visiting Salt Lake City?”[2]

Those concerns, sometimes unspoken but more often than not spoken aloud, offered some telling insights into the public’s perception about Mormons as the new millennium dawned. Despite a rash of dire predictions in this vein from a number of media voices, the 2002 Salt Lake Olympics did not become the so-called “Mormon Games.” Well-publicized fears about the LDS Church’s oppressive community presence never materialized; in fact, by all accounts, the opposite was true. As one columnist put it, the Mormons, in the end, “looked golden.”[3]

This story, a sort of apprehension-to-appreciation story, is something that Professor Richard O. Cowan has been researching for most of his academic career. His 1961 Stanford dissertation dealt with “Mormonism in National Periodicals”—and his findings are very relevant in this 2002 Olympic story. As he traced journalists’ treatment of Mormons from 1830 to 1960, he found that a positive uptick in Mormon-related reporting corresponded with a “change from the early interest in the Saints as a ‘peculiar people’ believing in curious theological doctrines, to an interest today in Mormonism’s programs for the total well-being of the Saints as well as in the individual and collective accomplishments of the Mormon people.”[4] In essence, that description also seems to apply well in describing the changing arc of the media’s attention to Mormons during the 2002 Olympic season—an arc that moved from a focus on Mormon peculiarities to a focus on Mormon people. It was a shift that would have an impact long after the Olympic Games’ closing ceremonies.

Background—and Battlegrounds

In order to appreciate just how significant the 2002 Olympics were in the recent history of the public perception of Mormonism, one must understand just how bleak things were for Mormons, from a public image standpoint, by the early 1990s. And it was a change that had come on rapidly. Gallup recorded a public favorability high-water mark for Mormons in 1977, when the polling organization reported that 54 percent of Americans held an opinion of Latter-day Saints that fell somewhere on the favorable side of Gallup’s measurement scale.[5] Gallup’s findings came during the LDS Church’s Homefront heyday, when radio and television commercials about family solidarity played across the nation. George Romney, J. Willard Marriott, Johnny Miller, the Osmonds—these were Mormons that the public knew and liked.

But in the late 1970s, a new chapter on the reputation of institutional Mormonism was about to open—and an unexpected one at that, based at least on a 1973 opinion survey commissioned by the LDS Church’s Public Communications Department. Respondents in 1973 ranked the LDS Church relatively low in comparison to other denominations when it came to perceptions of secrecy and suspicion, and even lower in terms of public influence.[6] Mormons seemed wholesome, happy, and benign.

Only a few years later, though, the Church’s active opposition of the Equal Rights Amendment at the end of the decade alarmed some commentators who worried about the underappreciated political clout that the highly centralized and wealthy Church could wield when it wanted to—and that clout threatened not only those on the political left who saw Mormonism’s sense of morality as anachronistic and repressive, but also those of the new Christian Right who wanted to make very clear the religious divide that separated Mormons and traditional Christians. The God Makers, a film which premiered in late 1982, gained rapid popularity for setting that divide in the starkest of terms, as it painted the LDS Church in ominous, even satanic, hues. When the Mark Hofmann bombing and forgery scandal made front-page news nationwide in 1985, the repeated accusations from so many sides about Mormonism’s secrecy, its authoritarianism, and its bizarre history and practices could not be easily sloughed off by the Church’s press representatives. Not only did these types of descriptions make a measurable dent on Mormonism’s public standing—only half as many Americans viewed Mormons favorably in 1991 as did in 1977[7]—but these descriptions also would prove to have remarkable staying power in setting the terms of discussion about Mormonism over two decades later.[8]

The Barna Research Group noted in its 1991 survey about American attitudes toward various church groups that “the only denomination in the survey”—a survey which also included questions about Baptist, Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian, and Lutheran churches—“for which more Americans had a negative impression than a positive impression was the Mormon church, also known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints”; 37 percent ranked Mormons unfavorably in 1991, while only 18 percent gave Mormons an unfavorable rating in Gallup’s 1977 poll. When those who expressed no opinion were removed from Barna’s sample, the 1991 results were even more dramatic: “Nearly six out of ten people who had an opinion of the Mormon Church said their impression was a negative one.”[9] This reversal of reputational fortunes was not lost on LDS Church headquarters. In 1989, Church leadership had restructured its Public Communications and Special Affairs department—renamed “Public Affairs” in 1991. In 1993, a specially commissioned task force made up of Mormon media types, called the Communications Futures Committee, finalized its recommendations for the Church after a yearlong study—recommendations that included things like modifying the Church’s logo to emphasize “Jesus Christ,” hiring an outside public relations firm, and tapping into the potential of the emerging “information superhighway.” Both for Church employees and outside advisers, the watchword was “proactivity.”[10]

Members of the United States Olympic team hold the American flag that flew over the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. The flag was carried into Rice-Eccles Olympic Stadium during the playing of the national anthem at the Olympic Ceremonies of the Salt Lake 2002 Olympic Winter Games. (Photo by U.S. Navy Journalist 1st Class Preston Keres.)

Members of the United States Olympic team hold the American flag that flew over the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. The flag was carried into Rice-Eccles Olympic Stadium during the playing of the national anthem at the Olympic Ceremonies of the Salt Lake 2002 Olympic Winter Games. (Photo by U.S. Navy Journalist 1st Class Preston Keres.)

These advocates for outreach found their standard bearer in Gordon B. Hinckley, sustained as the Church’s fifteenth president in March 1995. At the Communications Futures Committee’s urging, the Church had retained the services of the New York-based public relations firm Edelman Group. Edelman and President Hinckley proved a potent combination. The Edelman Group arranged for a “meet the press” lunch at the Harvard Club, and it was at that lunch that President Hinckley agreed to sit for an interview with 60 Minutes’ Mike Wallace. “Can you tell me,” Wallace asked in that interview, as if to underscore just how remarkable he found the occasion, “the last President of the Mormon Church who went on nationwide television to do an interview with no questions ahead of time so that you know what is coming?” The interview and the attendant 60 Minutes feature, which aired in April 1996, signaled something of a sea change to the wider media world and foreshadowed the type of Mormonism that would be on display in 2002.[11]

Then, in 1997, Church Public Affairs got a dry run for Olympic press coverage, and unexpectedly so. That year, independent Mormon pioneer enthusiasts planned to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Latter-day Saints’ overland trek to Utah with a full-scale reenactment. Dozens of wagon teams prepared to make the sesquicentennial trip, and it became a media phenomenon. The visual images of the Mormon trek recalled all that was heroic and romantic about the American West, so photographers and television crews flocked to the high plains of Wyoming. While LDS Church officials did not initiate the wagon-train commemoration, they were ready to join in the telling of the pioneer story. Public Affairs specialists employed a new technology—CD-ROM—to distribute maps, pioneer journals, and statistics about the LDS Church’s worldwide membership to journalists.

The surprise for Church representatives was just how widely the story played. It quickly took on an international flavor, as Public Affairs hosted reporters from Japan to Ecuador. Elder M. Russell Ballard said in August 1997, “When we can finally assess the number of newspaper articles and the extent of the television and radio coverage of the sesquicentennial, we will likely find that the Church has had more media exposure this year than in all the other years of our history combined.”[12]

After some of the low points of the 1980s, this was a season of optimism indeed for Mormons. Church membership hit the ten-million mark in 1997, one year after statisticians announced that more Mormons now lived outside the United States than in the U.S. In 1998, President Hinckley announced plans to nearly double the number of LDS temples across the globe, such that the Church would have a hundred temples in operation by the year 2000. These markers of growth and President Hinckley’s openness fostered a new tone, a new self-confidence, as the Church approached a new millennium. But all was not rosy in Salt Lake. Community excitement over hosting the 2002 Olympics was dealt a devastating blow near the end of 1998. A scandal was unfolding. Salt Lake Olympic boosters had stooped to what appeared to be all-out bribery to secure the city’s right to host the Olympics. Some of the principal organizers of the Olympic Games were implicated in the subsequent investigation—though eventually acquitted of illegal activities—and they left their posts with the Games in shambles. Debts were mounting, and community enthusiasm was diminishing. The disillusionment was real—and from a Mormon perspective, guilt by association was a real possibility. Several of the prominent figures in the bribery scandal were Latter-day Saints; possibly worse, in much of the public mind, Salt Lake City and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were inseparable.[13]

Some Utah Mormons even asked out loud if the Games should be returned to the International Olympic Committee (IOC). There was an almost universal recognition that the execution of the Games would inevitably reflect on The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, for better or for worse. And to some observers, the potential for reputational disaster was just too high after the scandal.[14]

But other Utah leaders proposed a different course: draft Mitt Romney. The Boston venture capitalist was the son of one of the most well-known Mormons of the previous generation, Michigan governor George Romney. The younger Romney had made a name for himself with business smarts and a hard-fought but ultimately unsuccessful run for the Senate in Massachusetts in 1994, against heavyweight Ted Kennedy no less. Still, when Utah Olympic booster Kem Gardner and Utah governor Mike Leavitt came calling, Mitt Romney was hesitant, to say the least, about taking on the Olympic challenge.

By Romney’s own admission, it was his wife’s urging that swayed him. She “reasoned that if the Olympics were in jeopardy, if Utah was in trouble and our country embarrassed, that these were compelling reasons for leading a turnaround.” Boston insurance executive David D’Alessandro talked with Mitt Romney while Romney was mulling over the Olympics job offer, and D’Alessandro saw the way Romney’s family and faith ties to Utah factored into the decision to take on the troubled games. “I think he took [the job] because he felt that the Mormons were in trouble. He never said that, but I think he saw the scandal as a stain on his religion.”[15]

Mitt Romney immediately began looking for a second-in-command chief operating officer, and he ultimately persuaded Fraser Bullock to join the organization. Bullock, like Romney, had been at Bain Capital and, like Romney, was also a Mormon—and Bullock, too, had worried about the way the Olympics reflected on the people of Utah.[16] But it was this very personnel choice that upset, paradoxically, some Utah Mormons who balked at Mitt Romney’s appointment. There were grumblings about cronyism, from a business angle but also from a religious angle. One well-publicized complaint was that Romney was trying to turn the Salt Lake Olympic leadership team into a Mormon one.[17]

Fraser Bullock remembered how these religious-based criticisms caught him and Mitt Romney somewhat off guard. Romney later wrote that he “would never have guessed that a religion would be such a big matter for the Olympics.” Both quickly realized, though, how sensitive some Utahans were to anything that could potentially exacerbate Mormon/

Perhaps never was that dynamic set in clearer relief than over the question of alcohol sales at the Olympics. As Mitt Romney related the story, he and his committee made the decision in 2000 that alcohol would not be sold at the downtown Medals Plaza, since they wanted that venue to be a place where families with children could enjoy evening celebrations and concerts. What Romney conceived of as a gesture of responsible planning instead lit off a firestorm of local criticisms about Mormon attempts to impose religion on outsiders. The irony for Romney was that his home city in Massachusetts—Belmont—was a “dry” (no alcohol sales) city because of community concerns there about drunk driving and family friendliness. But when the subject of alcohol restrictions came up in Utah, it was immediately branded a religious issue.[19]

Romney said that the Salt Lake Tribune’s editor Jay Shelledy “opened [Romney’s] eyes” that debates about alcohol laws in Utah were proxy for debates about religion. And those debates were fraught with historic tension that played out in the media.[20] Part of that tension, and the resultant criticism of Romney’s committee in Utah, was simply because this was the Olympics. Observers have long noted what has almost become a media truism connected with the Olympic Games, regardless of the host city: the local media is always harder on Olympic planners than are national or international media. Local journalists need to fill their columns and their airtime for several years before the Olympics, so they scrutinize, as might be expected, every development related to preparation for the Games. This seemed especially true in Salt Lake City, where the bribery scandal had put the public’s media watchdog on high alert.[21]

But there also was no question that the Mormon element made the level of tension in the local media something uniquely Utahan. Thus charges of Mormon cronyism reverberated loudly, as did accusations of behind-the-scenes-type puppeteering on the part of the Mormon hierarchy. The reality was that the Salt Lake Olympic Committee top management team was made up of people from around the country with diverse backgrounds—the majority of whom were not Latter-day Saints.[22] But the perception of Mormon control of Utah and its people (and the specter of past Mormon control) gave rise to national unease about the “Mormon Games.”

Myths and Realities

If this mix of worries—past and present, local and national—was coloring predictions of a 2002 “Molympics,” then President Gordon B. Hinckley’s announcement in 2000 that the LDS Church would not proselytize during the Olympics changed the tone of the entire picture.[23] The announcement served as much in its symbolism as it did in its practicality and generated almost universal nods of appreciation—and, from some, sighs of relief.[24] Striking the right “good partner” balance was not always easy, but the decision not to proselytize seemed, over time (and especially in retrospect), to do just that for two groups of Mormons who had been walking the same tightrope simultaneously, but from different ends.

On one side of that tightrope, there were Latter-day Saints who worked in official capacities in running the Games themselves. This was Mitt Romney, Fraser Bullock, Lane Beattie, Governor Mike Leavitt—these were the Mormons who worked with or for the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC). They were carrying the load of pulling off a successful Olympics, and the universal consensus was that the SLOC needed the LDS Church in order to do that. The trick, Mitt Romney and team learned, was to balance their requests so that the LDS Church was not doing too much. There was a feeling at the Church (and Mitt Romney picked up on this when he took over the helm) that Romney’s predecessors had been expecting too much of the Church—not because the Church wasn’t willing to help, but because Church leaders were sensitive to the aforementioned perception of their cultural dominance, and they thus wanted to broaden opportunities for participation by the full community. These were Utah’s Olympics, President Hinckley consistently reminded the Church’s Olympic liaisons. Hence President Hinckley demurred when Mitt Romney’s SLOC asked to use the Church’s massive printing presses, for example; President Hinckley wanted to give that business to community printers.[25]

Banner of figure skater adorning the Church Office Building in downtown Salt Lake City during the 2002 Olympic Winter Games.

Banner of figure skater adorning the Church Office Building in downtown Salt Lake City during the 2002 Olympic Winter Games.

Another case in point: a Mormon working for SLOC, Alan Barnes, put together in the late 1990s a community Interfaith Roundtable group that met monthly for several years in advance of the Olympics. The Roundtable was conscientiously inclusive, reaching out to dozens of representatives of faith groups throughout Utah. Ray and Janette Hales Beckham represented the LDS Church on the Roundtable. The Beckhams were appointed volunteers serving on the Church’s Olympic Coordinating Committee, which consisted of Church Apostles Robert D. Hales and Henry B. Eyring, along with a rotating member of the Church’s Seventy and a member of the Presiding Bishopric. While the Beckhams were energetic participants in the Roundtable, they declined to chair the Roundtable when their colleagues from the various denominations invited them to do so. Instead, they offered to support the leadership of their interfaith partners as needed. This meant that when the various churches of the Roundtable were charged by SLOC and community officials with providing temporary living space for Salt Lake City’s transient population during the Olympics, the LDS Church provided the bedding and the foodstuffs from Welfare Square, and then fill-in volunteers from local LDS congregations to serve the meals.[26]

This sensitivity to the appropriate level of LDS Church involvement did not only come from the LDS Church institutional side. When the Church’s Olympic Coordinating Committee offered to fill some of the athletes’ downtime by setting up a family history center in the athletes’ village, Fraser Bullock said that Games organizers decided to nix that idea. They worried that the center would seem too overtly promotional of Mormonism.[27]

So while both sides emphatically took a wall-of-separation approach to the administration of the Games, the Church in the end did win applause for its role as a community supporter. That included making available significant swaths of real estate, like the parking area around—and road access to—the Olympic Park where the sledding and ski jump competitions were held and the downtown plaza where every night medal ceremonies and free concerts drew in huge crowds. Bullock also reported that the Church, unlike other landowners or community partners, never asked for any compensation in exchange for the use of its properties. Beyond that, the Church donated five million dollars to build the infrastructure at the medals plaza and concert site.[28]

But that donation showed just how precarious walking this thin public opinion line could be. It was ironic to Mitt Romney that his committee’s request for the Church’s downtown property led to publicized complaints that the LDS Church was attempting to steal the show by again foisting itself on the Games. Romney held a press conference in 2001 to address these persistent charges, and among other things tried to make it clear that the plaza site had come at SLOC’s initiative rather than the Church’s. “I was brought up to thank people who made gifts,” Romney told reporters, “not criticize them. I have to say thank you for the contribution of the Medals Plaza land and funds to build it out for free concerts.” The press conference was a self-conscious “orange juice and champagne” affair as Romney’s team made clear that “these are Games for America. . . . They’re Episcopal. They’re Catholic. They’re Muslim. They’re Jewish. They’re Mormon. They’re Baptist.”[29]

So heated did the “Mormon Olympics” rhetoric become that Utah congressman Jim Hansen felt it necessary to give a speech in October 2001 before the US House of Representatives to “dispel the notion that the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the 2002 Winter Games is somehow beholden to or acting improperly in concert with the LDS Church”—insinuations that Representative Hansen found distasteful in Newsweek’s feature of September 10, 2001, “A Mormon Moment.”[30]

Of course, Jim Hansen’s speech came in a much different world than did Newsweek’s feature, even though they were separated only by a month. The horrific tragedies of September 11, 2001, changed every conversation across the United States, including every conversation about the 2002 Winter Olympics. While increased security became an obvious concern, just as real were the concerns about American national unity, international cooperation, and religious understanding. Everyone connected with the Games understood the suddenly new significance of the Olympics as a time for bringing the peoples of the world together—and a sense of mission united the Olympic community.[31] It was a delicate balancing act, with some slips and missteps, but the outcome, by all accounts, was a community partnership that proved indispensable in the making of the 2002 Winter Games. When a SLOC subcommittee had not enlisted enough local families to host the families of visiting athletes only weeks before the Games began, Ray Beckham used Church contacts to fill the quota in a matter of a few days. He also arranged for Latter-day Saint volunteers to staff the Games’ twenty-four-hour call center when organizers were faced with glaring gaps.[32] This became the Church’s modus operandi, to respond to behind-the-scenes needs in support of the community when asked—and send strong signals of support of the Games in public. Church-owned Brigham Young University announced plans that it would suspend classes for two weeks in February 2002 so that its students could work as volunteers at the Games. Mormon officials went one step further by asking local leaders to read in Church meetings a letter encouraging members to join the volunteer effort.[33] The response was overwhelming, and it became one of the lasting legacies of the Salt Lake City Olympics.

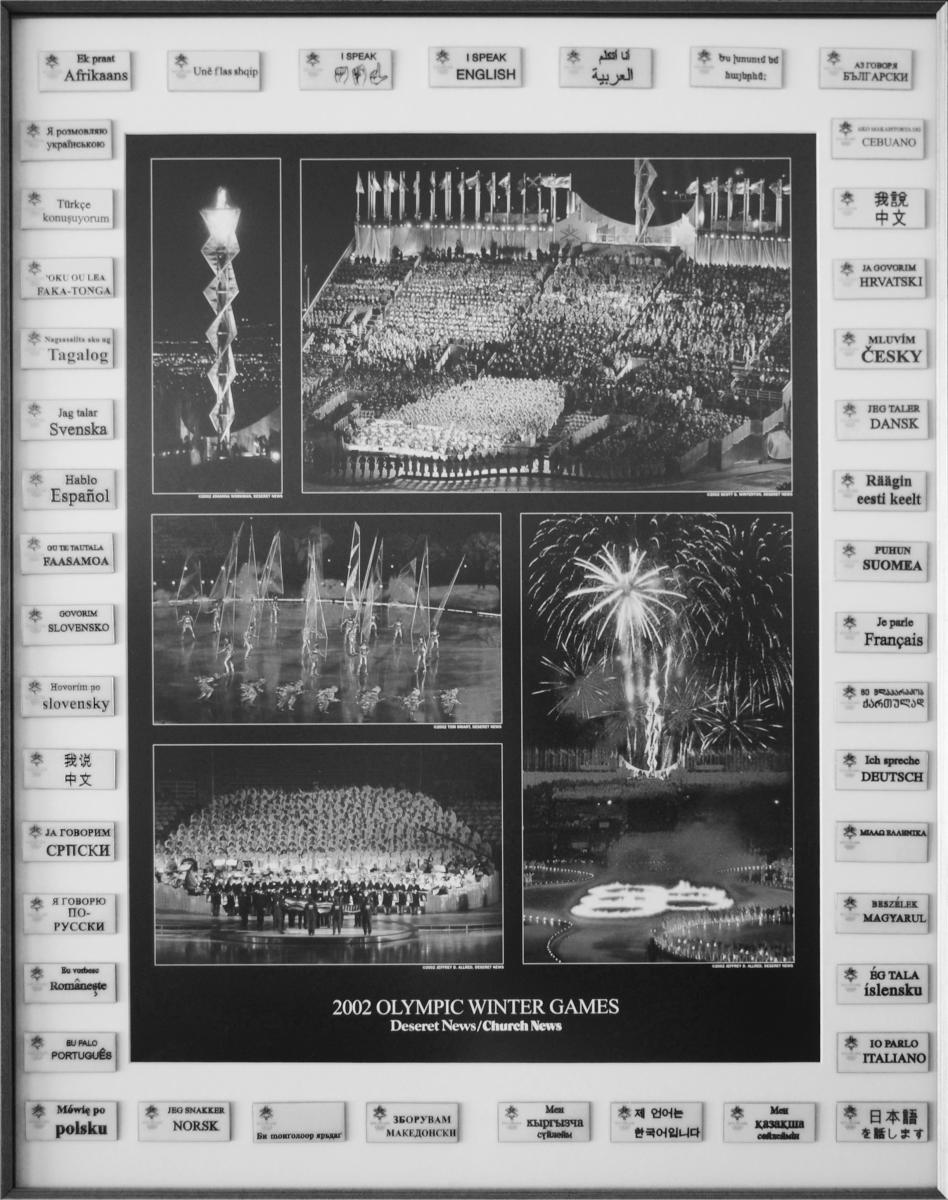

Two hallmarks came to characterize the 2002 volunteers. First was their dependability—and this even caught organizers by surprise. Because, historically, Olympic volunteers usually dropped out at a rate somewhere in the range of 15–20 percent, organizers planned to overstaff their volunteer ranks. What caught everyone off guard was that the Utah volunteers showed up; the attrition rate was less than 1 percent.[34] The other hallmark was the volunteers’ language ability. Never before, foreign visitors repeatedly marveled, had they found so many volunteers who could speak those visitors’ native languages. IOC chairman Jacques Rogge specifically singled out the 2002 volunteers and their foreign-language facility in his praise of the Games. He told reporters at the end of the Games that while Mormons—and especially the Church’s leaders—“were never pushing issues, you know, absolutely not. . . . I have been greeted at many venues in Dutch, . . . my mother language, at least 20 times by different volunteers who told me, ‘I have been on a mission in your country.’”[35]

Ray and Janette Hales Beckham's "I Speak display, featuring a collage of photos from the 2002 Olympic Winter Games framed by pins that designate languages spoken by volunteers at the Games. (Photo by Laura Haws.)

Ray and Janette Hales Beckham's "I Speak display, featuring a collage of photos from the 2002 Olympic Winter Games framed by pins that designate languages spoken by volunteers at the Games. (Photo by Laura Haws.)

Of course, many Utah volunteers were not Mormons. The full community, in all its diversity, rightfully earned the accolades that the volunteers repeatedly received. But as with so many aspects of the Games, the public’s identification of Salt Lake City with Mormonism meant that praise for the volunteers often reflected positively on the LDS Church and its missionary program. And that, perhaps, underscores the principal point of this paper. The issue at hand is public perception. Therefore, despite conscientious decisions not to influence the running of the actual Games—and in this vein, perhaps no greater compliment could be paid to those Mormons who faced that difficult hands-off balance than Rogge’s comment that the LDS Church had been “absolutely invisible to us” while he was at the Salt Lake Olympics[36]—LDS Church officials also accepted the reality that Mormonism would always be visible, in the backdrop, in the Games’ spotlight spillover.

This, in a sense, was the challenge for the other group walking that metaphorical tightrope mentioned earlier: the Mormons charged professionally and officially with responding to media queries. Anyone who has even casually watched the Olympics knows that the reporting is always about more than sports—this is another Olympic coverage truism. Media outlets send crews of journalists to generate “color” pieces, stories about the culture and history and people of the host city. What was inescapable to every observer in the months leading up to 2002 was just how ubiquitous the LDS Church would be in these types of stories—so ubiquitous that Newsweek’s Kenneth Woodward used a phrase that would keep its currency for a decade. He called the Olympics a “Mormon Moment.”[37]

Church Public Affairs representatives knew that scores of reporters would be knocking at their office doors—and come they did. Over 3,300 reporters visited the Church’s temporary News Resource Center in the Nauvoo Room of the Joseph Smith Memorial Building on Temple Square. “It was just constant,” Michael Otterson remembered of that stream of journalists. “It was exhausting, but it was incredibly exhilarating.”[38] Otterson’s team had “scoured the community to find” people “who would be willing to volunteer” at the media center—or even to be “on call” if volunteers with second-language skills were needed. Public Affairs managing director Bruce Olsen recruited former BYU communications students from around the West—especially those with language skills—to come as volunteers to staff “regional” desks at the center. These Public Affairs representatives themselves gave dozens of interviews a day and coordinated interviews with Church leaders as well. Training this army of Church volunteers—and these volunteers were separate from SLOC’s cadre of volunteers—fell to a team organized by Janette Hales Beckham. They called their program “Friends to All Nations.” This phrase became the Church’s Public Affairs calling card during the Olympics, a trademark that appeared on its website and trading pins and commemorative dinner plates. The volunteers’ training focused on openness, friendliness, and helpfulness—as well as an emphatic reiteration of President Hinckley’s commitment that Mormons would not proselytize during the Games.[39] Once again, it seems difficult to overstate the impact of that policy. This move diverted much of the public’s focus from concerns about the Church as an institution, thus opening up column inches and bandwidth for features on Mormons as individuals. As Richard Cowan and several of his graduate students have persuasively shown over the years, the media’s treatment of the Latter-day Saint people has followed a steady, century-long trajectory of positive reporting.[40]

The Public Affairs Department reported to the Church’s First Presidency that it was not “placing stories just to increase column inches or to receive any kind of coverage. We are looking for media stories that help . . . solve problems that affect the reputation of . . . the Church or help the public better understand issues that affect the Church.” In its five-year plan preceding the Olympics, the department designed “a web site specifically oriented to journalists,” as well as “press kits,” and video and photography packages to “be made available to visiting journalists and posted on the Internet media site.” The very existence of a website was an innovation that grew out of Church preparation for the Olympics. “Our strategy,” department officials concluded, “is to provide a number of stories for the national and international media so that the only story about the Church is not Mountain Meadows or polygamy—substitute positive for negative.”[41]

These prepackaged vignettes included a ten-minute Myths and Reality video hosted by two famous Mormons: star NFL quarterback (and Brigham Young descendant) Steve Young and former Miss America Sharlene Wells Hawkes. The pair tackled several prevalent misconceptions: Do Mormons practice polygamy? Do Mormons only “take care of their own” when it comes to humanitarian relief aid? Are Mormons Christians?

This focused counteroffensive against negative stereotypes, together with the other Olympics-timed media vignettes, yielded measurable results. Public opinion surveys conducted by the Church demonstrated that “feelings toward the LDS Church have improved significantly.” Survey respondents in 2002 rated the Church five points higher than they did in 1998—from 40.3 to 45.3—when asked to measure their feelings on a “0 to 100 thermometer scale,” with 0 representing a “very cold, negative feeling,” and 100 representing a “very warm, positive feeling.” The poll results were even more significant in terms of targeted misunderstandings. When asked, “As far as you know, do members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints believe in Jesus Christ?,” 81 percent of respondents answered “yes” in 2002, as opposed to 68 percent only one year earlier. An overwhelming majority of those surveyed in 2002 (80 percent) also answered that the LDS Church “discouraged” polygamy. Overall, Public Affairs officials saw these trends as indicating that “knowledge about the LDS Church has steadily increased.” Surveyors asked, “How much do you feel you know about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whose members are sometimes called Mormons?” The number of people who answered “a great deal” doubled between 1998 and 2002 (from 7 percent to 14 percent), those who said “some” increased by two-thirds (from 25 to 41 percent), and those who answered “very little” decreased by a third (from 67 percent to 46 percent).[42]

These statistics seemed directly proportional to other indicators that pointed to the effective reach of the media initiatives that the Church had put into place. The website that Public Affairs created for the media tallied over 900,000 hits between June 2001 and May 2002. As Public Affairs tracked “the number of news stories that were generated” around the world, “they were in the thousands”—“nothing like we have ever seen,” Otterson remembered. The sheer volume of coverage was staggering, but more telling were some of the headlines—from the Denver Post: “Utah’s efforts deserve medal”; from the Portland (Maine) Press Herald: “Mormons add to, not detract from, Salt Lake City Games”; and from the Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette: “Olympics give people the chance to see the real Mormon faith.”[43]

Olympic Legacies

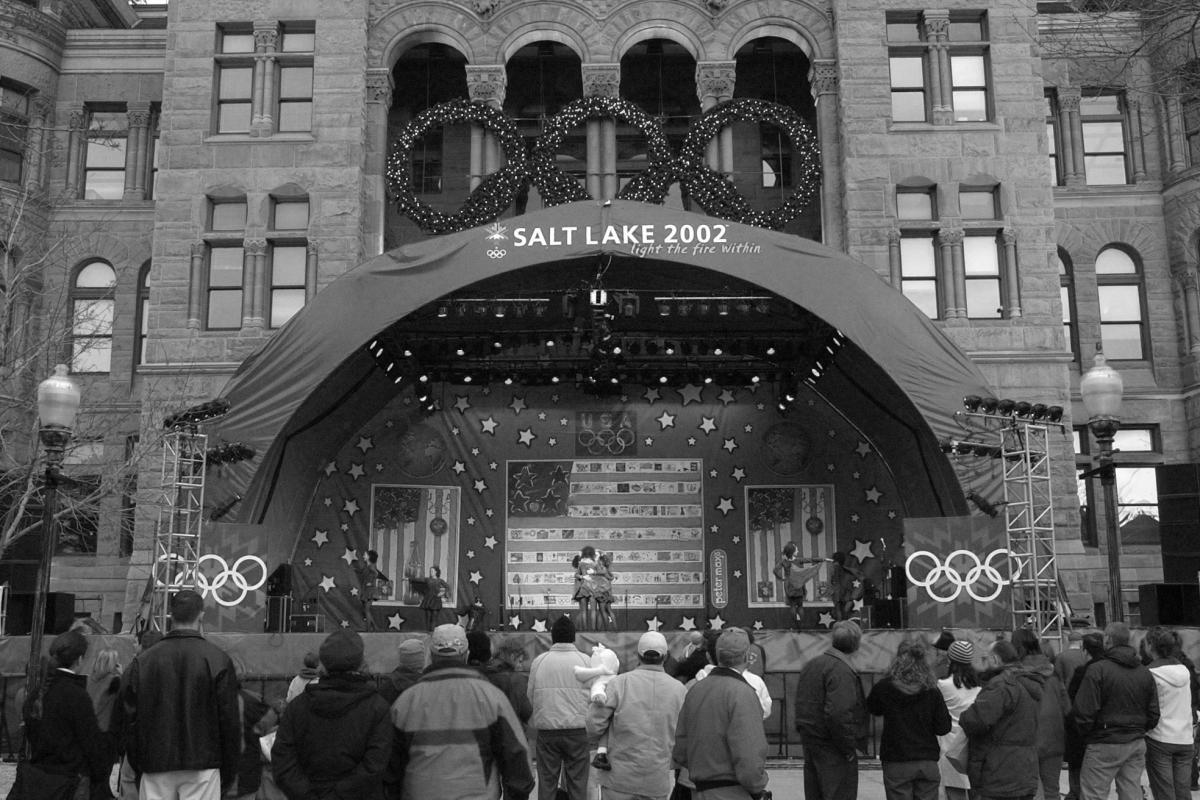

There were several Olympic images that Mormons hoped would linger, like NBC anchorman Tom Brokaw’s interview of President Hinckley. Brokaw described the Mormon leader, then ninety-one years old, as “an energetic, enormously thoughtful man.” A columnist for the Washington Post noted that “the Tabernacle Choir shared top billing with the celebrities; Temple Square got almost as much TV time as Bob Costas.” Editorials in the Washington Times and the Chicago Sun-Times gave the Olympic hosts “gold” ratings for the quality of the games, both for the hospitality of the locals as well as the success of the Church’s efforts to “overcome stereotypes.” The Chicago Tribune concluded that “the church’s contribution turned into a plus after years of fear that these would be the Mormon Games.” President Hinckley told the Church’s April 2002 general conference that “visitors . . . who came with suspicion and hesitancy . . . feeling they might get trapped in some unwanted situation by religious zealots . . . found something they never expected.” Outsiders agreed. “The subtle approach, in the end, was a brilliant move by the church,” one columnist wrote. “The only religious shenanigans and Bible-thumping at the Winter Games came courtesy of angry other denominations, whose members circled Temple Square with anti-Mormon signs and pamphlets and posters.” The irony was that, in the end, “everyone looked nutty except the Mormons, who looked golden.”[44]

BYU's Folk Dancers performing at the Salt Lake City and County Building compels on February 21, 2002. (Photo by Jaren Wilkey, courtesy of BYU Photo.)

BYU's Folk Dancers performing at the Salt Lake City and County Building compels on February 21, 2002. (Photo by Jaren Wilkey, courtesy of BYU Photo.)

Now, with more than a decade’s worth of historical hindsight, some legacies launched for 2002 have proven to be lasting. The Interfaith Roundtable still hosts annual community music events. The LDS Church’s web presence has expanded significantly and become an integral part of the Church’s approach in communicating with Church members and the media and other interested parties. Lane Beattie says that after the Olympics, surveys done by Wirthlin International have shown that Utah’s stock has continually risen among visitors, thanks in large part to the picture the Olympics provided of Utah’s people.[45]

And, of course, Mitt Romney’s growing national profile fueled a successful run for the governorship of Massachusetts in 2002 and two unsuccessful runs for the US presidency in 2008 and 2012—campaigns that raised media coverage of Mormons to another unprecedented benchmark. In many ways, it is almost impossible to consider the attention given to Mitt Romney and his Church in 2008 and 2012 without starting with the Olympics; Michael Otterson has persuasively argued that the much-talked-about “Mormon Moment” in 2008–12 was not really a moment at all, since attention to Latter-day Saints had really never abated after the 2002 Olympics.[46] The Salt Lake Tribune’s Peggy Stack recorded this exchange with an Olympics journalist: “The Salt Lake City Olympics were like ‘a coming-out party for Mormons,’ says Hank Stuever, who covered the Games as a feature writer for The Washington Post, ‘that gave people a vernacular about Mormonism they didn’t have before, and that [interest] has sustained itself in pop culture.’” [47]

For many people in the United States and beyond, press coverage of the 2002 Olympics became their introduction to Mormons—and by all accounts, that coverage looked different than it would have in, say, the late 1980s. Considering the past dozen years since those Winter Games, then, while it is apparent that public attention to Mormonism has continued to come in waves, what seems most true about the impact of the 2002 Olympics on Mormonism’s public image was that it signaled in reality a rising tide of favorability.

Notes

[1] Lane Beattie, interview by author, February 5, 2013, transcript, 4. I am grateful for a grant from the Religious Studies Center at Brigham Young University that made possible the interviews and transcriptions quoted in this essay.

[2] See, for example, Ana Figueroa, “Salt Lake’s Big Jump,” Newsweek, September 10, 2001, 52.

[3] Hank Stuever, “Unmentionable No Longer: What Do Mormons Wear? A Polite Smile, If Asked about ‘the Garment,’” Washington Post, February 26, 2002, C1. See also Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Remembering the ‘Mormon’ Olympics That Weren’t,” Salt Lake Tribune, February 17, 2012, http://

[4] Richard O. Cowan, “Mormonism in National Periodicals” (PhD diss., Stanford University, 1961), 192.

[5] See Question qn19k, The Gallup Poll #978, June 14, 1977, accessed at Gallup Brain database.

[6] See “Attitudes and Opinions Towards Religion: Religious Attitudes of Adults (over 18) Who Are Residents of Six Major Metropolitan Areas in the United States: Seattle, Los Angeles, Kansas City, Dallas, Chicago, New York City—August 1973,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, 17, Provo, Utah.

[7] See Barna Research Group, “Americans’ Impressions of Various Church Denominations,” September 18, 1991, copy in author’s possession, 1.

[8] For an extended discussion of the impact of these 1980s-era controversies and their bearing on media coverage of Mormonism during Mitt Romney’s presidential campaigns, see J. B. Haws, The Mormon Image in the American Mind: Fifty Years of Public Perception (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[9] Barna Research Group, “Americans’ Impressions of Various Church Denominations,” 3; emphasis added.

[10] See Haws, The Mormon Image, 161–65.

[11] Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 540.

[12] M. Russell Ballard, “Sharing the Gospel Message through the Media,” in Out of Obscurity: Public Affairs and the Worldwide Church (Provo, UT: David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies, 1998), 5; see also Richard B. Wirthlin, “Public Affairs Challenges for the Growing, Global Church,” in Out of Obscurity, 10. This paragraph is derived from Haws, The Mormon Image, 170.

[13] See Peggy Fletcher Stack, “Olympic Corruption Revelations Embarrass Mormon Church Officials,” Religion News Service, January 27, 1999, 1, retrieved from http://

[14] See Romney, Turnaround, 25.

[15] For Ann Romney’s perspective, see Romney, Turnaround, 6; David D’Alessandro is quoted in Michael Kranish and Scott Helman, The Real Romney (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 207.

[16] See Fraser Bullock, interview by author, May 18, 2012, transcript, 18; and Romney, Turnaround, 67–70.

[17] See Romney, Turnaround, 272–73, for Jon Huntsman Sr.’s concerns along these lines.

[18] See Bullock, interview, 6; and Romney, Turnaround, 269.

[19] See Romney, Turnaround, 276–80.

[20] Romney, Turnaround, 278. Romney wrote, “In fact, the Church never got into the alcohol debate” (279).

[21] See Michael Otterson, interview by author, October 25, 2013, transcript, 1–2; and Bullock, interview, 11–14.

[22] See Bullock, interview, 13–14: “when you look at our top management team of fifteen people, at SLOC . . . five out of fifteen” were LDS, “so any notion that these were the ‘Mormon Olympics’” did not reflect “the diversity that we had.” Bullock estimated that Mormons made up “20 percent” of the organization’s “top forty” supervisors, and then noted, “Now, volunteers? Different story.”

[23] See Vania Grandi, “Mormons Eager for Olympics but No Heavy Recruiting When Games Reach Utah,” (Jacksonville) Florida Times Union, December 15, 2000, B-4, retrieved from http://

[24] See Ray Beckham and Janette Hales Beckham, interview by author, June 13, 2014.

[25] See Beckham interview; and Romney, Turnaround, 273–76.

[26] See Beckham interview. For an overview of the members and the accomplishments of the Interfaith Roundtable, see Peggy Fletcher Stack and Kathleen Peterson, A World of Faith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, in partnership with the Interfaith Roundtable of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee for the Olympic Winter Games of 2002, 2002), viii–xi.

[27] See Bullock, interview, 5–6; Beckham interview. See also Romney, Turnaround, 280.

[28] See Bullock, interview, 1, 19.

[29] Romney, Turnaround, 281–82.

[30] James V. Hansen, “A Mormon Moment,” capitolwords, October 2, 2001, http://

[31] See this local perspective from volunteer Maughn Lee: “The big thing that overshadowed the whole thing was 9/

[32] See Beckham interview.

[33] See Romney, Turnaround, 271.

[34] See email correspondence with Fraser Bullock, July 20, 2014; Lee interview, 4. See also Beckham interview.

[35] Lisa Riley Roche, “Rogge Hails Olympic Village, Heaps Superlatives on Games,” Deseret News, February 25, 2002, http://

[36] Mike Wise, “Olympics: Closing Ceremony; Games End with a Mixture of Rowdy Relief and Joy,” New York Times, February 25, 2002, http://

[37] See Kenneth L. Woodward, “A Mormon Moment,” Newsweek, September 10, 2001, 46. The Church’s managing director of Public Affairs, Michael Otterson, notes that the phrase may have been coined in a November 2000 U.S. News and World Report article by Jeff Sheler about the Houston Temple and attendant LDS growth. See Michael Otterson, “More than a ‘Mormon Moment,’” On Faith, March 15, 2012, http://

[38] Otterson, interview, 3–4, 7. See also Beckham interview; and “Public Affairs—Building on a New Foundation of Heightened Recognition for the Church—Resource Review, June 25, 2002,” Public Affairs Department, internal document, copy in possession of the author, 17.

[39] See Otterson, interview, 3–4; and Beckham interview.

[40] For a summary of these studies and the assessment that the media’s focus on Mormon people and programs generated generally positive commentary, see Casey W. Olson, “The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in National Periodicals: 1991–2000” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007), 128–34.

[41]“Focus for Public Affairs Work: First Presidency Presentation, December 18, 2002,” copy in possession of the author, 5; “Public Affairs Department: Five-Year Plan, 2000–2004,” copy in possession of the author, 13; Otterson, interview, 3; “Public Affairs Department: Semi-Annual Report to the First Presidency—October 17, 2001,” Public Affairs Department, internal document, 3. This paragraph, and the four that follow, are derived from Haws, The Mormon Image, 173–75.

[42]“Public Affairs—Building on a New Foundation of Heightened Recognition for the Church—Resource Review, 25 June 2002,” 3–6.

[43] Otterson, interview, 5; see also Chuck Green, “Utah’s Efforts Deserve Medal,” Denver Post, February 17, 2002, B01; Jenn Menendez, “Mormons Add to, Not Detract from, Salt Lake City Games,” Portland (Maine) Press Herald, February 17, 2002, 1D; and Sonia Patton, “Olympics Give People the Chance to See the Real Mormon faith,” Charleston (West Virginia) Gazette, February 23, 2002, 1C.

[44] Tiffany E. Lewis, “Media Spotlight Shines on Church,” Ensign, May 2002, 111; Stuever, “Unmentionable No Longer,” C1; “U.S. Takes Gold as Perfect Host,” Chicago Sun-Times, February 26, 2002, 23; Eric Fisher, “2002 Winter Olympics were as Good as Gold,” Washington Times, February 26, 2002, A1; Chicago Tribune, February 25, 2002, as quoted in Lewis, “Media Spotlight Shines on Church,” 110; and C. G. Wallace, “Olympics Gave Mormonism Chance to Shine, Leader Says,” San Diego Union-Tribune, April 7, 2002, A4. See also Felix Hoover, “Mormons Get the Word Out: Olympics Improved LDS Church’s Image, Scholar Concludes,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, March 8, 2002, E1; and Brandon Griggs, “Games Bright Spot in Otherwise Grim Year,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 2003, A1.

[45] See Beattie, interview, 3–5.

[46] See Otterson, “More than a ‘Mormon Moment.’” See also the chart “Mormon Mentions in the Media,” in Jim Dalrymple II, “The Mormon Moment Is Finally (Really) Over,” BuzzFeed, June 12, 2014, http://

[47] Stack, “Remembering the ‘Mormon’ Olympics That Weren’t.”