The Mormon Pavilion at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair

Brent L. Top

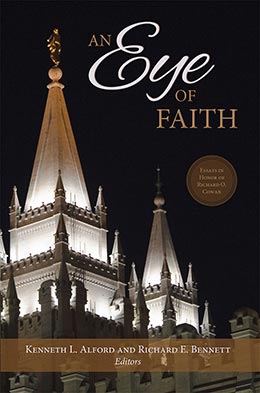

Brent L. Top, “The Mormon Pavilion at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 321–47.

Brent L. Top was dean of Religious Education at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

Side view of the Mormon Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair. (Photo by Grant Bethers.)

Side view of the Mormon Pavilion at the 1964 New York World's Fair. (Photo by Grant Bethers.)

When Richard O. Cowan left Stanford in 1961, PhD in hand, to join the Religious Instruction faculty at BYU, he did not know the impact he would have on the study of LDS Church history by students and scholars, Latter-day Saints and those not of our faith. His dissertation focused on perceptions of Mormonism found in national periodicals. He could not have known in 1961 how perceptions of the Church would dramatically change over the next half century or how the media itself would change and how the Church would use that media to further its mission. Yet Dr. Cowan spent his fifty-three-year career observing, recording, and interpreting those dramatic changes.

I joined the BYU Religious Education faculty and became a colleague to Richard in 1987. From that day I also became his student—learning from him through his writings, presentations to the faculty, symposia, and other less-formal settings. I learned quickly that if I needed to know anything about LDS Church history in the twentieth century, Richard was the man who knew the most. Likewise, if I needed to know about the history of temples or missionary work, Richard was the man who could teach me. His book The Church in the Twentieth Century had a powerful impact upon me. It instilled in me a strong desire to learn more about that period of Church history in general, but more specifically, to research and write about the Church’s use of exhibits and pavilions at world’s fairs to present the message of the gospel to the world. The quintessential professor, Dr. Cowan taught me things I did not know, and more important, he inspired me to dig deeper and learn even more. This paper is my humble attempt to build upon what I first learned from Richard about the Mormon Pavilion at the 1964–65 World’s Fair. As we celebrate Richard’s fifty-plus years of studying, teaching, and writing about missionary work, temples, and modern Church history, it is appropriate that we also commemorate the golden anniversary of the Mormon Pavilion and its role in each of those areas.

Reading the New York Times at the breakfast table, as was his usual custom, G. Stanley McAllister noticed a headline in the Monday, August 10, 1959, edition—“World’s Fair Planned Here In ’64 at Half Billion Cost.” The article, by Ira Henry Freeman, reported that the planning committee wanted the fair to “celebrate New York’s 300th anniversary” and be “bigger than any exposition previously held anywhere.”[1] McAllister slapped the newspaper down on the table and exclaimed, “The Church has got to be represented there,” and he rose from the table with a firm resolve to make that happen.[2] What happened thereafter surpassed even his lofty aspirations. Hopeful that the New York World’s Fair could be a vehicle to increase Church visibility and missionary success in the East, McAllister could not have known how such unprecedented involvement would influence the manner in which the Church would present its message to the world in the twenty-first century. The purpose of this paper is twofold: (1) to provide a retrospective of the Mormon Pavilion at the 1964–65 World’s Fair, and (2) to discuss how it continues to influence Church missionary and public relations efforts.[3]

Beginnings

McAllister had conceived his idea a generation earlier to build a major exhibit or pavilion in New York City to help the Church tell its story. His missionary service in the Eastern States Mission from 1920 to 1923 instilled in him the desire to “make a name for himself and the Church in the East.” Even before completing his mission and returning to his home in Salt Lake City, McAllister spoke of “desires within him to return to the Eastern States.” He viewed his release as a missionary as only a temporary absence.[4] Not long after his marriage, McAllister returned to New York City to study at NYU and begin a career. In 1929, he accepted a position with the Columbia Broadcasting System as director of buildings and plant operations and was instrumental in helping to secure the weekly nationwide broadcast of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir for the CBS Radio Network.[5] In 1946, he left CBS and took a position as an executive with a major New York department store, later advancing to an executive position in the parent company. Influential in business, civic affairs, and the Church, McAllister was, indeed, on his way to making “a name for himself and the Church in the East.”

In that same year, a continent away, Apostle Mark E. Petersen proposed that the Church establish “a publicity department for the Church.”[6] This would not happen for another decade. In 1957, the Church Information Service (CIS) was established, and it would go on to play a significant role in the Mormon Pavilion saga.

Making the Decision to Participate

Stanley McAllister, who had become president of the New York Stake in 1960, continued to pursue his dream of having the Church participate in the New York World’s Fair. He put together a team of influential local Church members and leaders to explore the possibility and prepare a proposal to the Church. When senior Church leaders were in New York City, he would tell them about his idea and seek their support. One particularly influential leader to whom McAllister often spoke was Henry D. Moyle, counselor in the First Presidency. Enthusiastic about the prospects, Moyle recommended that McAllister contact Elder Mark E. Petersen, now the director of the CIS. In 1961, McAllister recommended to Elder Petersen and the First Presidency that the Church participate in the fair. However, for several months, nothing came of President McAllister’s suggestions and prodding. But he was not easily dissuaded and continued to be the driving force behind the project.[7]

The initial reaction of Church leaders to the invitation to participate was to do a small exhibit and information booth from which Church literature could be distributed. The Church had used exhibits at fairs, conferences, and expositions for many years as a way to share the Church’s message and inform the public of the Church’s origin.[8] However, it was indeed a large leap from these minor projects to what President McAllister envisioned. He continued to push hard for “a monumental presence at the fair.”[9]

Because of the urgency to make a decision regarding whether the Church would have a booth or pavilion presence at the fair, Church leaders asked Apostle Harold B. Lee to head a planning committee that would present plans and recommendations to the First Presidency. On June 25, 1962, Lee, on assignment in New York, told them that he doubted the Church would be interested in building its own pavilion, but would probably want to have a small booth manned by a set of missionaries. As evidenced by a later incident, the primary reason behind Elder Lee’s reluctance was the financing of such a project: Bernard P. Brockbank, a newly called General Authority and the managing director of the pavilion, informed Church leaders that the cost of the planned pavilion would be about three million dollars. He recalled that Elder Lee “threw his hands in the air and he said, ‘We do not have anywhere near that amount of money.’ He said, ‘If you feel that your estimate is anywhere near correct, cancel us out and we will not hold the World’s Fair because I would not think of going to the Brethren with a three million dollar cost.’”[10]

Never before had the Church (or even the state of Utah) spent more than one hundred thousand dollars for the displays, exhibits, and other costs related to participation in world’s fairs or expositions.[11] After World War II, the Church spent considerable monies in an extensive period of building suitable meetinghouses for its members, particularly in Europe. This created a significant strain on the economic condition of the Church. At headquarters it was projected that in 1961, the budget deficit could be over twenty million dollars. At the time Church leaders were considering the prospects of spending three million dollars or more for participation in the New York World’s Fair, the Church “faced a liquidity crisis and deficit of $9 million.”[12] No wonder Harold B. Lee and the First Presidency were initially so reluctant. Despite this initial reaction, they, nonetheless, deliberately considered every aspect of the proposal—its costs and its potential. To McAllister, however, the process couldn’t move fast enough.

Adding to concerns regarding cost was the report that other religious groups participating at the fair were spending extraordinary sums on their pavilions and elaborate displays. The Catholic group was even bringing in priceless art masterpieces from the Vatican, including Michelangelo’s famous statue Pietà and altar paintings The Last Judgment and The Good Shepherd. There were other equally impressive pavilions from religious denominations, some of which had been designed by the leading architects in the country, including the Billy Graham Evangelical Association’s pavilion. These impressive buildings created a degree of competition among the religious sects, which vied not just for visitors but for converts.[13] Elder Brockbank felt that the Church’s pavilion needed to be impressive so it wasn’t overshadowed by other religious pavilions. He told Elder Lee, “We have the Lord’s program and the truth and we ought to be in competition with these others, . . . and they will have a difficult time no matter how much they spend showing false doctrines.”[14]

Despite the discouraging response of Elder Lee, the report was completed and sent to Elder Petersen and the CIS committee with a recommendation to build a major pavilion. Several weeks passed with no word from the Brethren of acceptance or rejection of the proposal. Meanwhile, on August 20, the World’s Fairs Operations Department announced that all of the sites previously discussed with Church officials were no longer available and that the deadline to accept the invitation to participate was also imminent. A worried President McAllister, fearing his dream to be slipping out of his grasp, personally telephoned President David O. McKay. Within a day or two, President McKay called back to inform him that the First Presidency had approved the proposal. He requested that President McAllister negotiate with the New York World’s Fair Committee for the best site available.[15]

Elder Mark E. Petersen and the CIS Committee also worked to develop a theme and plans for the needed exhibits. President Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency, meeting with the committee, advised them to “‘do the job right,’ saying that the Church would appropriate necessary sums. Figures of a million or two million dollars were suggested and President Moyle repeated: ‘Let’s do it right.’”[16]

The "Mormon" Pavilion at the New York World's Fair featured a 127-foot-tall replica of the eastern spires of the famed Salt Lake Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The center spire was capped by a gold-leafed fiberglass statue of the angel Moroni. The pavilion included two large exhibit halls, a spacious gallery, two movie theaters, and several consultation rooms. The grounds were attractively landscaped with more than fifty large tress, several hundred shrubs, and over one thousand flowers. At the foot of the tower was a reflecting pool. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

The "Mormon" Pavilion at the New York World's Fair featured a 127-foot-tall replica of the eastern spires of the famed Salt Lake Temple of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The center spire was capped by a gold-leafed fiberglass statue of the angel Moroni. The pavilion included two large exhibit halls, a spacious gallery, two movie theaters, and several consultation rooms. The grounds were attractively landscaped with more than fifty large tress, several hundred shrubs, and over one thousand flowers. At the foot of the tower was a reflecting pool. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

Site Selection

Five possible pavilion sites were available to the Church. Unfortunately, when the CIS committee indicated their first choice to fair officials, they found it was no longer available, and no other site was acceptable to both parties. McAllister asked an influential personal friend, who was a friend of fair president Robert Moses, to intercede for the Church. His friend was able to secure the site that was the Church’s second choice: near the front entrance, next to a proposed food pavilion that had been an eyesore at the Seattle World’s Fair. Dr. Kenneth Beesley, New York Stake mission president, explained, “However, as events developed, what was our second choice turned out, in fact, to be even preferable to what had been our first choice through circumstances that we could not have foreseen. The sponsors of the Food Pavilion went bankrupt.”[17]

This unexpected turn of events provided the Church with a very visible and impressive location, as the first pavilion to be seen by visitors entering via the main gates, adjacent to a major subway stop. Rather than leave an unsightly vacant lot where the food pavilion would have been, the fair officials worked with the Church landscapers to create a garden. Irvin T. Nelson, landscape and pavilion grounds architect for the Church, turned the adjoining vacant lot into a garden. Nelson’s objective was to provide a place of beauty and peace. Fair visitors confirmed that this was indeed the result. In addition, the regular workers at the fair informed Brother Nelson that they had unofficially voted the Mormon exhibit “the most beautiful of the entire fair. . . . Your plantings are food for the soul.”[18] The exhibit was also lauded for its beauty by Robert Moses, and finally the American Association of Nurserymen presented Nelson with a national award for outstanding work.[19]

The official agreement with the New York World’s Fair was signed by President McKay on October 10, 1962, in the First Presidency’s board room. Stuart Constable, vice president of operations for the fair, expressed his pleasure at having the Church represented at the fair and assured those present that the site of the Mormon Pavilion was one of the best sites in the fairgrounds. President McKay responded to Constable that it was appropriate that the Church have a choice site, since “nothing can be too good for the Lord, and this is the Lord’s Church.”[20]

“Man’s Search for Happiness”

While the site selection process was under way, David W. Evans, brother to Elder Richard L. Evans, president of Evans Advertising and member of the CIS staff, had developed a theme for the Church’s pavilion after fasting, prayer, and contemplation. The theme of the fair itself was “Man’s Search for Truth.” Brother Evans suggested substituting the word “happiness” for truth, reasoning that it was “the common denominator or theme that would interest and satisfy the greatest number of people, whether Christians, Jews, Mohammedans, Buddhists, agnostics, infidels, young, old, learned, ignorant, rich, poor.”[21] Thus the now-familiar theme “Man’s Search for Happiness” was conceived and later approved for the Mormon Pavilion.

The other important step in the planning phase was the design for the pavilion. It was agreed by all that the design should be something readily recognizable and uniquely associated with Mormonism. The design ultimately accepted unanimously by the committee was suggested by Elder Evans and his brother David. They both had grown up in a home on the Avenues in Salt Lake City and were very familiar with the many Mormon landmarks in the city. “Hundreds of times I had walked down the First Avenue hill looking towards the temple spires,” recalled David. “They were unforgettable as I have viewed them so often towards the sunset. It took no creativity on my part to suggest that we make them our central theme.”[22] In early November 1962, the First Presidency approved the design for the pavilion, whose façade would be a replica of the three eastern spires of the Salt Lake Temple. President McKay expressed the pride of the Church in having such a building to house its exhibits on the fairgrounds.[23]

The Movie That Almost Wasn’t Made

When it was announced that the Church would build a pavilion for the New York World’s Fair and that the pavilion would house two movie theatres, Wetzel O. “Judge” Whitaker and his associates at the Brigham Young University Motion Picture Studio were eager to be involved in the film production. They envisioned an important mission for the BYU film studio in helping to declare the gospel message to the Church and the world. Whitaker and his staff approached the Brethren and asked that the BYU production unit be considered for the project and proposed a film to be entitled What Is a Mormon? The ideas were presented to Elder Evans, who commented that he very much liked their ideas and was sure that one day such a film would be made, but he informed them that the Church’s pavilion committee seemed to be interested in having a West Coast film production company produce the film. The BYU team was dejected, but after a meeting with Elder Lee in which the Apostle encouraged them to fast and pray about the project, there seemed to be an important change. The day after their special fast, when President McKay was asked who he thought should produce the film for the pavilion, he said, “‘Why, BYU, of course,’ as though there could be no question.”[24]

Elder Lee, whose thoughts may have been influenced by the recent passing of his wife, charged them to produce a film on “the three great questions of life: where we came from; our purpose and reason for being here upon the earth; [and] what happens to us after death.” Whitaker and his associates’ earlier excitement and enthusiasm was soon subdued when they realized the enormousness of the project. Faced with these potential technical obstacles, Scott Whitaker, Judge’s brother, decided instead to produce a film on Joseph Smith’s First Vision. He was convinced that that event was one of the greatest stories that could be told by the Church and that it could also be a dramatic visual experience when portrayed on film. However, he recalled Elder Lee’s reaction to this new idea when it was presented. “That’s a beautiful story,” replied the Apostle kindly, “and it will be told on film someday [it was completed in 1976], but I would like a story on the three great questions: where we came from; our purpose and reason for being here upon the earth; what happens to us after death.”[25]

Most all of the religious pavilions showed films or multimedia presentations. The film shown in the Protestant Pavilion generated considerable public interest and controversy. The film, entitled Parable, was directed by Rolf Forsberg and commissioned by the New York City Protestant Council. Film critics praised the film for its “art house sensibilities” and its provocative use of “enigmatic symbolism,” portraying Jesus Christ as a redeeming clown and mankind as a traveling circus. Newsweek proclaimed it “very probably the best film of the fair.”

While some critics and audiences appreciated and embraced the film, many people were deeply offended and sought its removal from the fair, including the New York World’s Fair president, Robert Moses.[26] So divisive was the film that the director received death threats. This controversy, perhaps, drove more people to the Mormon Pavilion to see a much different kind of film: Man’s Search for Happiness. One particular visitor to the Mormon Pavilion commented on the stark contrast of the two films. The Reverend Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, one of America’s most famous religious leaders and authors, “voiced his disapproval as he came out of the projection room [in the Protestant Pavilion after watching the film Parable]. Someone asked him, ‘Have you seen the Mormon film?’” Peale had indeed visited the Mormon Pavilion and seen Man’s Search for Happiness. He responded that in thirteen minutes, he was

told the story of where we came from, why we are here, and where we are going. . . . The film motivated one to want to make the most of earth life, and the last two minute[s] of the film were the most touching, the most inspirational, and most revealing of any two minutes of a film I have ever seen in my entire life. . . . Out of this film, I learned two things: (1) An entirely new concept of the purpose of life and its connection with the eternities; (2) An entirely new concept of the importance of the family in connection with the eternities.[27]

Artists, Sculptors, and Display Builders

The Church also wanted many paintings and displays housed in the Mormon Pavilion. As early as 1962, David Evans began his search for talented artists to be involved. From lists he had acquired from the Seattle World’s Fair management, he began a search that spanned the nation and even reached beyond the Atlantic. From this search emerged some of the best and brightest sculptors, painters, and display builders who could use their God-given talents to portray the important and unique teachings of the Church.

Three major sculptures became an integral part of the pavilion. The central focal point of the pavilion’s exhibition hall was to be the Christus, a marble duplicate of a statue by renowned Danish sculptor Berthel Thovaldsen, which was made for the pavilion by Aldo Rebechi of Florence, Italy. Two other sculptures were done by members of the Church: Dr. Avard Fairbanks, noted sculptor and professor of art at the University of Utah, created a statue commemorating the restoration of the Melchizedek Priesthood; Elaine Brockbank Evans, sister of Bernard Brockbank, was commissioned to create a statue of Adam and Eve. In addition, two impressive murals, each 110 feet long, were painted to hang in the gallery of the exhibition building.

Besides the statues and murals, there were also dioramas and models. One model in particular was destined to evoke a great deal of interest; it depicted Joseph Smith, as a boy, praying in the Sacred Grove. Also developed were revolving displays illustrating the “Six Major Tests of Primitive Christianity” and the “Apostasy and Restoration.”[28] Each of the statues, murals, dioramas, and displays was designed to complement the overall message of the pavilion. These displays would later play an important role in future exhibits.

Construction and Operation

The months of planning, drawing architectural plans, building models, and designing displays culminated in early 1963 as construction began. The muddy marshland of Flushing Meadows, New York, posed significant challenges to construction workers. Because the soil was so wet, piles had to be driven deep within the earth to serve as part of the foundation for the building that would house pavilions and exhibits for the fair. After a brief ceremony to commence construction, the delegation of officials and press representatives went to the fair administration boardroom for a luncheon, where Elder Lee officially unveiled a model of the Mormon Pavilion. One unique feature of the Mormon Pavilion, as explained by Elder Lee, captured the attention of primarily the New York press and later the national press: the components of the pavilion were designed in such a manner that, at the closing of the fair, they could be dismantled and used for the construction of chapels for the Church in the New York area.[29]

During the construction of the pavilion, the mounting of the angel Moroni statue atop the main spire of the pavilion façade drew hundreds of observers, newspaper and media reporters, and other fair representatives.[30] The Church News began its story of the event by reporting, “The Angel Moroni ‘flew’ to New York this week.”[31] Irene Staples, who served as a missionary at the pavilion during 1964–65, told of another humorous event: “Before the Fair was over,” Staples recalled, “one Catholic church contacted officials of the Mormon pavilion wanting to know if they could buy this angel or one like it to put atop their new church which they were building. Their request was graciously denied, [the Mormon leaders] thinking that Moroni would feel uncomfortable atop a non-LDS chapel.”[32]

Despite the monumental challenges of building on marshland, L. Tom Perry, then a member of the New York Stake, recalled, “The construction was beautifully done—just a masterpiece.”[33] Nearly a quarter of a century after the construction of the Mormon Pavilion, Elder Brockbank still marveled over the quality of the finished product. He remembered the sunlight coming through a special golden glass and creating “a halo in [the pavilion] and at night we had lights outside that would keep the halo and . . . the reflection . . . so we would get that halo for the full period of time even when the sun was down a little earlier. It was remarkable.”[34]

The Mormon Pavilion was dedicated by President Hugh B. Brown, of the First Presidency, in a private ceremony on Monday, May 18, 1964. The next day the New York Times reported “the largest assemblage of . . . Mormon officials to gather in the East since the Mormons went West in 1846 convened yesterday morning to dedicate the Mormon Pavilion.”[35] Seven of the fifteen members of the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles were present for the dedication of the edifice and grounds that would provide, as President McKay described, “one of the most unique and effective missionary efforts in [the Church’s] history.”[36] Within the first few weeks of the pavilion opening, attendance figures surpassed expectations.

David W. Evans planning the Church's World's Fair exhibit. Evans was one of the account supervisors for the Mormon Pavilion project and creator of the theme, "Man's Search for Happiness." (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

David W. Evans planning the Church's World's Fair exhibit. Evans was one of the account supervisors for the Mormon Pavilion project and creator of the theme, "Man's Search for Happiness." (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

The Use of Missionaries as Tour Guides

One of the unique, though somewhat controversial, aspects of the operation of the Mormon Pavilion was the use of full-time missionaries as tour guides. Elder Brockbank, as a newly called General Authority who had been serving the previous three years as a mission president in Scotland, brought a missionary zeal that would permeate every aspect of the exhibits and activities of the Mormon Pavilion. Many of the ideas generated by the Church Information Service and the public relations firm hired by the Church in the early planning of the exhibits reflected a “soft sell” approach to preaching the gospel and disseminating information about the history and teachings of the Church.[37] Even some of the senior leaders of the Church were concerned about the possibility of negative reaction to such direct proselyting. They were concerned that it could damage the Church’s image and defeat its purposes by appearing too “pushy.” It was proposed that exhibits have displays started by electronic buttons, rather than have tour guides presenting the message. However, Elder Brockbank felt strongly that such a “soft sell” approach would not produce the desired results for the pavilion. He emphatically asserted that the exhibits must proclaim the gospel message, not merely inform visitors. He felt that missionaries must be used to maximize the effects of the exhibits and to add a personal, spiritual element to the pavilion. L. Tom Perry, a young high councilor from the New York Stake on the pavilion planning committee, “led [in 1963] a more bold and more direct approach” to telling the story, stating that the “soft sell” approach had never been successful in proclaiming the message of the Church. “Imagine what would have happened,” Elder Perry stated, “if Moses had decided to use a soft-sell approach.” Although some visitors criticized the very direct proselytizing approach utilized at the Mormon Pavilion, “it was the right decision,” Elder Perry observed. “[The missionaries] had a profound effect on the people as they would come in.”[38]

Such an idea had never really been tried before, to the extent that Elder Brockbank was proposing, and many concerns remained. However, his suggestion was finally accepted, and “a corps of more than 70 missionaries of the Eastern States Mission [served] continually at the fair as guides.”[39] Elder Brockbank recalled the importance of having missionaries serve in the pavilion: “Our missionaries became our most interesting exhibit. We had the pictures . . . [as] visual aids plus their own spiritual witness and so on and they became very effective. It just was a miracle how they could explain things.”[40]

Despite these public relations concerns about the use of missionaries as a potential risk, the wisdom of the decision was ultimately borne out by a major study of public perceptions of the various pavilions and exhibits at the fair. Richard J. Marshall, vice president of the Evans Advertising Agency who worked closely with David Evans in overseeing the work of the Mormon Pavilion, recounted an interesting exchange with Warren Brooks, public relations director of the Christian Science Church. Brooks, who knew Marshall through the advertising industry, left a prestigious advertising agency to work for the Christian Science Church. At the New York World’s Fair, Christian Scientists had been represented in the Protestant Pavilion with several other denominations. It was their intent, however, to have their own pavilion at the World’s Fair that was to be held in Montreal two years later. Brooks wanted to meet with Marshall and talk about what Marshall learned from their experiences at the New York Fair. Marshall invited Boyd K. Packer, president of the New England States Mission, to join him at the lunch meeting with Brooks. Marshall remembered that Brooks stated

he had just studied a major survey contracted by the combined Protestant church which had participated in the [New York] World’s Fair. . . .

“The consensus of the survey, an in-depth study done [on] religious pavilions throughout both years of the New York World’s Fair, is that you Mormons won hands down for friendliness and human appeal,” he stated to Brother Packer and me. “You beat the Catholics, Jews, Protestants—all of us combined.”

“Terrific,” said I. “And what was it that scored highest for us? The movie? Our paintings? The Christus statue? The dioramas?”

“No,” said Warren. “None of those. The thing that got top score was your ushers. You had the greatest ushers in the whole fair.” He paused and smiled. He wanted a favor of us. “My board of directors wanted me to find out how long it takes you Mormons to train your young ushers.” It was Brother Packer who answered.

“Nineteen years.” Brother Packer stated with a smile. “It takes nineteen years to train a Mormon usher.”[41]

Special Events and Projects

Numerous factors contributed to the success of the Mormon Pavilion. No one thing or event was more significant than another. Capturing the immediate interest of fair visitors was the awe-inspiring architecture and breathtaking beauty of the pavilion. The carefully designed displays and murals were both instructive and inspirational. In addition, several special projects drew additional visitors and media attention.

Several musical events at the pavilion generated a great deal of favorable publicity for the Church. The World’s Fair Committee designated July 24, 1964, as Utah Day and invited the Mormon Tabernacle Choir to perform an open-air concert. The choir also gave two concerts at the legendary Carnegie Hall. In addition to the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, a three-hundred-voice Mormon Mothers Choir attracted the interest of the public and press, not only because of their music but also because of who they were and the lifestyle they represented. Finally, sizable crowds came to see performances by the King Family and the Osmond Brothers. Besides presenting a favorable image to the public, these events helped draw people to the pavilion who might otherwise not have come.

One other special project perhaps drew even more attention and touched more people than all of these concerts. It was the brainchild of Bradley MacDonald of Santa Cruz, California. Brother MacDonald, with the help of a Santa Cruz Ward and New York Stake members, arranged for the daily donation, packing, free air transportation, and pickup of giant begonia blossoms from California, beginning in the late summer of 1964. More than forty thousand blossoms were used for the fair, not only in the reflection pool but also as corsages for dignitaries who visited the Mormon Pavilion. Irene Staples also arranged the begonias into large, beautiful bouquets and took them to all of the other major pavilions in the fair. Attaching an Article of Faith card, she would write a brief message, “Best wishes to our good neighbors.” Her efforts did much to further goodwill among the pavilions and heighten interest in the Church’s exhibit. Bradley MacDonald summarized the success of the Begonia project: “The tremendous good that the begonias have done in bringing beauty to the Pavilion can never be completely realized. For as we would be putting them out on the islands in the reflection pool, many people would stop and after looking at the beautiful flowers say, ‘My it is so beautiful here, let’s go inside and see what it is like.’”[42]

Controversy

Despite overwhelmingly positive comments by visitors and favorable media coverage of the special events, the Mormon Pavilion was not without controversy. In the early 1960s the Church’s policy banning blacks from priesthood ordination was only beginning to emerge as a controversial issue. There had been some limited media coverage, and a few influential voices were calling for the Church to rescind the ban. At the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair, however, there was little attention given to that position of the Church. Organizers had expected and were prepared for some form of public demonstration or protest. There was talk that there would be a protest against the Mormons when the fair opened, but none materialized. There was a minor controversy related to race, but it was aimed at all of the pavilions. Elder L. Tom Perry remembered that a group of African-Americans were demanding equal employment for blacks in the various pavilions. Seeing none among the guides working in the Mormon Pavilion they demanded that the Church “hire” more blacks to work in the pavilion. “I remember President Brockbank invited them into the office,” Elder Perry recalled. “[He said to them,] ‘Well now, you are willing to come on the same basis that these young men are, same salary and everything else? Want to know how much [they make]? They are volunteers.’ And they picked up and walked out . . . when they found out that everybody in our pavilion was a volunteer and no one was being paid.”[43]

A more serious controversy arose four months after the fair’s opening. The headline of an article in the Jewish Ledger read “Mormon Mural Stirs New Dispute at Fair.” The author, Bernard Lefkowitz, reported that “it has taken the World’s Fair four months to reopen a 2,000-year-old biblical controversy.” The news article reported that Simon Bloom, editor and publisher of several Jewish publications, had visited the Mormon Pavilion and noted the caption to a painting of Christ’s crucifixion—“They crucified the Son of God between two thieves on Calvary.” Bloom asked who that was referring to and the young missionary stated, “The Jews. The Scribes and Pharisees crucified Jesus.” Bloom complained to the fair’s leaders, accused Mormons of being anti-Semitic, and reported the event in the Jewish press. Upon receiving word of Bloom’s accusations, Brockbank immediately removed the caption from the painting[44] and wrote to Simon Bloom, saying, “The missionaries have been counseled not to attempt to tie the crucifixion to any one group of people, but to leave the judgment for the offenders on this occasion to God.” He continued:

For men to continue condemning the Jews is a fallacy of man and a tool of Satan. The adversary continually seeks to place barriers and prejudice between groups of God’s children to cause feelings, friction, and even hatred among the tribes of Israel and among God’s children generally. History, as well as the scriptures, are full of enmity and evils of men and their traditions. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has never taught me, nor do you find it in its teachings, that the Jews or any group since the crucifixion are to be belittled or condemned for the acts of those responsible for the death of Jesus Christ. The Church of Jesus Christ does teach that all of God’s children should live as a family and love and assist one another.[45]

Although Brockbank’s removal of the mural inscription and subsequent apology letter mollified Bloom, reports of the event continued in Jewish publications years later as yet another example of Christian anti-Semitism.[46]

A Lasting Legacy

The impact of the Mormon Pavilion did not end with the closing of the gates to the New York World’s Fair on October 17, 1965. Even as the impressive final statistics were being calculated, the impact of the pavilion was continuing. Over fifty million people attended the New York World’s Fair in 1964–65, even though it was deemed a financial failure for fair organizers. For the Church, however, it was a remarkable success. The Mormon Pavilion hosted approximately six million visitors. Nearly a million guest register referrals were obtained and presented to the Missionary Department. Over five million Church tracts and pamphlets were distributed at the pavilion. Nearly one hundred thousand visitors to the pavilion bought copies of the Book of Mormon.[47] As planned, the pavilion was dismantled and used to construct the Long Island Stake Center in Plainview, New York. The statues, murals, and displays that had been carefully created for and effectively used in the Mormon Pavilion continued to draw crowds in new settings. In 1962, the Church completed a new Bureau of Information building on Temple Square. Many of the pavilion’s displays found a permanent home there. Others were used in visitors’ centers throughout the Church. However, the lasting legacy of the Mormon Pavilion was not merely statistics, buildings, and exhibits. Its profound impact was felt deeply in three important areas—missionary work, public perceptions of the Church, and the Church’s future exhibits and visitors’ centers.

The Impact on Missionary Work

On January 29, 1964, a mission conference of the Eastern States Mission was held in Manhattan to prepare the missionaries for the work in which they would engage at the Mormon Pavilion. Elder Lee promised them that they “would soon become part of the greatest missionary effort the Church [has] ever yet undertaken.”[48] Missionaries and members thereafter referred to the pavilion as “The Greatest Missionary.” President Wilburn C. West, of the Eastern States Mission, stated that the Mormon Pavilion had created “a great breakthrough in missionary work along the Atlantic Coast. . . . The Pavilion has given us a new vision of missionary work.”[49] One of the great challenges that missionaries faced in New York City in 1964 was city laws that prohibited door-to-door proselyting, which had been the traditional missionary approach for generations. After visiting the Mormon Pavilion, thousands invited missionaries to their homes to teach them about the Church. “The great break-through in missionary work resulting from our experience at the Mormon Pavilion is simply this,” President West observed. “We provided a vehicle for people to come to us. Having come to us they were more teachable than if we had gone to them.”[50] While no official statistics were kept of missionary lessons taught or baptisms performed as a result of attending the pavilion, no doubt such statistics would be staggering. For example, it is reported that during 1965, the New York, New Jersey, and Cumorah stakes (those stakes encompassing and adjacent to the New York World’s Fair) led the Church in convert baptisms.[51] David Evans remembered that the year previous to the fair there were only six convert baptisms in that area, but a thousand baptisms in each of the two years the fair was open and “in the succeeding several years, there were six to eight hundred per year.”[52] Elder Perry recalled that “the Regal Park Branch [New York Stake] was maybe 75 percent converts resulting from the World’s Fair.”[53] President George Mortimer of the New Jersey Stake observed that “every ward in the greater New York area benefited by converts . . . through the World’s Fair,” many of whom became some of the strongest ward and stake leaders in the area.[54]

The enormous increase in missionary activity resulting from the fair was not confined to the New York City area alone. Stacks of missionary referrals obtained at the pavilion continued to be used by missionaries throughout the world for years after the fair had ended. Even visitors to the pavilion who were not interested in the Church became “missionaries,” as they spoke about the Mormon Pavilion and showed the brochures to their neighbors. Once such case in Florida resulted in the baptism of those neighbors.[55] As impressive as the statistics and the observable results of the pavilion were, the story of the miraculous missionary work of the Mormon Pavilion will not be told in statistics but in individuals’ lives and testimonies. People felt the influence worldwide. Thousands of accounts of miraculous missionary experiences and conversions have been told through the years by missionaries, members, and pavilion visitors. Today there is even a Facebook page for people to record memories of and experiences with the Mormon Pavilion in the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair.

Although the Church had previously had a smaller-scale presence at world’s fairs and expositions, the presence at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair was the first major foray into what could be characterized as visitor-centered missionary work. The success of the Mormon Pavilion paved the way: not only for future visitors’ centers, but also for television commercials advertising free books and videos, inserts in popular magazines, billboards, and online campaigns such as Mormon.org, Mormon Messages, and “I’m a Mormon” media campaigns.

Impact on Public Perceptions of the Church

Nearly a million visitors to the Mormon Pavilion wrote comments in the guest register books. Less than one percent of the comments were negative. President Wilburn C. West reported, “The profound spiritual effect of our Mormon Pavilion will continue indefinitely. It has done more to change public opinion in this area and give the Church status than any other event in our lifetime.”[56] The original dream of a young Elder McAllister had become a reality, and it improved perceptions of the Church far beyond New York City. Prior to the fair, Mormonism was viewed primarily as a somewhat obscure and marginal religion. The Mormon Pavilion helped “create . . . a new image” that served to minimize old stereotypes and prejudices and “increased the Church’s visibility and help cast Mormon culture as part of the American mainstream.”[57] In the years immediately following the New York World’s Fair, positive stories about the Church appeared in leading national magazines such as Look, Saturday Evening Post, Newsweek, Life, Esquire, and Reader’s Digest, and in hundreds of media outlets throughout the United States and Canada.[58] There had probably never before been an event in the history of the Church that generated such extensive and positive media coverage.

The Mormon Pavilion at the 1964-65 New York World's Fair. (Photo by Grant Bethers, courtesy of Church History Library.)

The Mormon Pavilion at the 1964-65 New York World's Fair. (Photo by Grant Bethers, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Impact on Future Exhibits and Visitors’ Centers

David Evans, whose knowledge of display and exhibit techniques was unsurpassed, pointed out that “following the fair, the Church decided to participate in other major expositions . . . [and] also decided to build permanent visitors centers for exhibits and displays at key locations in many areas, beginning in 1966 with its largest and most impressive center on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, which used the ‘Man’s Search for Happiness’ theme and many of the paintings, dioramas, and other displays from the New York pavilion.”[59]

No doubt, one of the most important contributions of the 1964–65 Mormon Pavilion was the influence it had on other exhibits and the future usage of audiovisual technologies. Experience obtained from this exposition formed the philosophy and methodology of Church visitors’ centers. At the close of the Mormon Pavilion, Elder Brockbank assessed that “we now know a good deal more about how to blend visual aids with the spiritual testimonies of the priesthood. We’ve learned to simplify our approach, to stay with first principles, to preach the gospel of Christ in a vivid and forceful manner and still keep this a pleasant experience for everyone. We now look to making expanded use of this knowledge and these practices.”[60]

Indeed, the huge leap forward initiated by the Mormon Pavilion must be considered a seminal event in the evolution of the Church’s use of media in spreading its message to the world. From that time to the present day, the Church’s outreach through its use of technology and media has increased steadily and exponentially, including the hiring of an outside public relations firm to refine and expand its efforts to reach an even broader audience. Though not the first to embrace the Internet, the Church has developed sophisticated websites and ever-expanding media offerings where interested parties can learn more about Church teachings and practices, ask questions to “live” Church members, and read personal testimonies, all without ever speaking to a missionary if they choose. In 2014, the Church announced a feature-length documentary that was shown in movie theaters and will be shown on the Internet.[61] The path to this latest Church film is traceable to Man’s Search for Happiness and the Mormon effort at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair.

Even before initiating this unprecedented period of spreading the gospel message to the world via innovative and creative means, each phase of planning, development, and operation brought what those most closely involved with the Mormon Pavilion would characterize as “miracles.” To them, the hand of God was manifest in quiet, sometimes imperceptible ways, producing dramatic results. One observer concluded, “Credit for the most singular contribution must go to the Prophet David O. McKay. His was the vision to see what breath-taking achievements could be created in the name of the Lord with a masterful exhibit in the world’s mightiest market place. In a day and generation of enormous decisions, this must be considered divinely inspired.”[62]

While some may argue whether it was “miraculous” or “divinely inspired,” the Church’s innovative involvement in the New York World’s Fair can be inarguably characterized as seminal for the Church in the New York City area in the twentieth century. However, its influence reached far beyond the borders of New York, and its legacy continues to be felt into the twenty-first century and beyond.

Notes

[1] Bill Cotter and Bill Young, The 1964–1965 New York World’s Fair: Creation and Legacy (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008), 10. Cotter and Young further explain that the New York Times headline made it appear that New York’s hosting of the fair was a sure thing. Although yes, the planning committee’s proposal received the endorsement of Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., the proposal was anything but a sure deal. Other cities, including Los Angeles, Chicago, and Washington, DC, were also vying to host the 1964–65 World’s Fair. On October 29, 1959, President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that New York City had been selected to host the fair.

[2] Robert G. Vernon, McAllister’s stepson, wrote: “I was at the breakfast table with him the morning he first read the New York Times article announcing the Fair a few years hence. He immediately slapped the newspaper, exclaimed ‘the Church has got to be represented there,’ jumped up from the table, and then went to work to make it happen.” Personal letter to the author, November 7, 2000.

[3] Much of the history of the Mormon Pavilion included in this article has been published in the past. See Brent L. Top, “The Miracle of the Mormon Pavilion: The Church at the 1964–65 New York World’s Fair,” Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: New York, ed. Larry C. Porter, Milton V. Backman Jr., Susan Easton Black (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1992), 234–56; Brent L. Top, “Legacy of the Mormon Pavilion,” Ensign, October 1989, 22–28 ; Taylor Petry, “New York 1964 World’s Fair: Mormonism’s Global Introduction,” The New York LDS Historian 3, no. 2 (Fall 2000): 1–11; Nathaniel Smith Kogan, “The Mormon Pavilion: Mainstreaming the Saints at the New York World’s Fair, 1964–65,” Journal of Mormon History 35, no. 4 (Fall 2009): 1–52. This article, while recounting much of the same as these previous articles, introduces some materials and sources not previously published.

[4] Kenneth Fielding McAllister and Maridon McAllister Morrison, “The Life of Our Parents: G. Stanley & Donnette McAllister” (n.p., 2012), 15, https://

[5]“Biographical Note/

[6] Richard O. Cowan, The Church in the Twentieth Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1985), 289.

[7] Information concerning the involvement of G. Stanley McAllister in the Mormon Pavilion comes from “The Mormon Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1964–65,” an unpublished history and scrapbook compiled by Irene E. Edwards, MS 9138, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. This microfilm contains images of a three-volume scrapbook and unpublished history of the Mormon Pavilion that was submitted to the First Presidency years after the fair. No pagination is included in the work, and it will hereafter be cited as Staples, Scrapbook.

[8] See Reid L. Neilson, Exhibiting Mormonism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); see also Richard O. Cowan, The Church in the Twentieth Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1985), 166–67; see also Brent L. Top, “Tabernacle on Treasure Island: The LDS Church’s Involvement in the 1939–40 Golden Gate International Exposition,” Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: California, ed. David F. Boone, Robert C. Freeman, Andrew H. Hedges, and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (Provo, UT: Department of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University, 1998), 189–208.

[9] Kogan, “The Mormon Pavilion,” 12.

[10] Bernard Brockbank, interview by Brent L. Top, May 4, 1988, Salt Lake City, in author’s possession, 4. Richard J. Marshall, who along with David Evans was the account supervisor for Evans Advertising for the Mormon Pavilion project, reported that one of the factors in determining the success of a pavilion was the “cost per visitor.” Ford Motor Company’s pavilion had a $1.73-per-visitor cost compared to 12 cents per visitor to the Mormon Pavilion. Richard J. Marshall, “180 Points of Light,” unpublished personal reminiscences, 1989, 40, in author’s possession.

[11] Gerald Joseph Peterson, “History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1974), 70.

[12] Kogan, “The Mormon Pavilion,” 212.

[13] Peterson, “History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions,” 68–69.

[14] Brockbank, interview, 5.

[15] The timeline for the decision-making process is taken from a letter from Dr. Kenneth H. Beesley to Irene E. Staples, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[16] David W. Evans to Irene E. Staples, October 16, 1975, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[17] Kenneth H. Beesley to Irene E. Staples, December 13, 1976, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[18] Irvin T. Nelson, final report quoted by Irene E. Staples, “The Mormon Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1964–65,” in Staples, Scrapbook.

[19] Salt Lake Tribune, January 30, 1966, B-1, 4.

[20] Staples, Scrapbook (for report on the agreement signing, see Church News, October 27, 1962, 3).

[21] David W. Evans to Staples, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[22] David W. Evans to Staples, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[23] Church News, November 17, 1962, 3.

[24] Wetzel O. Whitaker, Pioneering with Film: A History of Church and Brigham Young University Films (Provo, UT: n.p., 1982), 57–58.

[25] Whitaker, Pioneering with Film, 59–60.

[26] Lindsay Clark Ross, “Parable (1964), directed by Rolf Forsberg,” https://

[27] Norman Vincent Peale, interview with T. Bowring Woodbury, May 20, 1964, CR 115, box 1, folder 4, Bernard Brockbank Files, Church History Library; hereafter cited as Brockbank Files. Elder Bernard Brockbank also quoted from this interview in a general conference address entitled “Missionary Work—Our Way of Life,” in Conference Report, April 1966, 16–18.

[28] Arnold Irvine, “Church Readies Pavilion for N.Y. Fair Inaugural,” Church News, February 29, 1964, 8–9.

[29] Richard J. Marshall, “Mormon Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair—A Progress Report,” Improvement Era, April 1965, 296. See also Church News, March 30, 1963, 3.

[30] Church News, March 14, 1964, 3.

[31] Church News, March 14, 1964, 3.

[32] Staples, Scrapbook.

[33] L. Tom Perry, interview by Brent L. Top, May 12, 1988, Salt Lake City, 1–2.

[34] Brockbank, interview, 5.

[35] New York Times, May 19, 1964, 34:2.

[36] David O. McKay, quoted by Richard J. Marshall, “The New York World’s Fair—A Final Report,” Improvement Era, December 1965, 1170.

[37] Peggy Petersen Barton, Mark E. Petersen: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1985), 134.

[38] Perry, interview.

[39] Henry A. Smith, “Dedication of Church’s World’s Fair Pavilion,” Church News, May 23, 1964, 8.

[40] Brockbank, interview.

[41] Richard J. Marshall, “180 Points of Light,” 44.

[42] Bradley MacDonald, “The Begonia Project,” in Staples, Scrapbook.

[43] Perry, interview.

[44] Brockbank Files, CHL; Jewish Telegraph Agency, September 18, 1964, http://

[45] Letter from Elder Bernard P. Brockbank to Simon Bloom, September 10, 1964, Brockbank Files, CR 115 1, box 1, CHL.

[46] See Morris Kominsky, “The Fraud of Deicide: Belated Efforts to Lay the Old Charge of ‘Christ-killer,’” Jewish Currents 22, no. 7 (July–August 1968): 24. It is interesting to note that the Jewish criticism cited was not unique to Mormonism. The Simon Bloom episode at the Mormon Pavilion was treated as what many Jews viewed as just another example in a long history of anti-Semitism resulting from Christians blaming Jews for the death of Jesus.

[47] Staples, Scrapbook.

[48] Wilburn C. West, “Missionary Service at the Mormon Pavilion,” in Staples, Scrapbook.

[49] Quoted by Richard J. Marshall, “The New York World’s Fair—A Final Report,” Improvement Era, December 1965, 1170.

[50] Wilburn C. West, “Missionary Service at the Mormon Pavilion,” in Staples, Scrapbook.

[51] David W. Evans to Irene E. Staples, October 16, 1975, in Staples, Scrapbook.

[52] David W. Evans to Irene E. Staples, October 16, 1975. It should be noted that the statistics cited are based on the remembrances of people involved in the operation of the Mormon Pavilion and Eastern States Mission and cannot be precisely substantiated, or refuted, by the author, since actual Church statistical records are unavailable.

[53] Perry, interview.

[54] Charles E. Hughes, G. Wesley Johnson, and Marian A. Johnson, “The Impact of the New York World’s Fair,” in The Mormons in Northern New Jersey (Provo, UT: New Jersey Mormon History Association, 1994), 126.

[55] Nelson Wadsworth, “Influence of Mormon Pavilion Felt Around Globe,” Church News, December 26, 1964, 6–7. Numerous other reports of conversions resulting from either direct or indirect exposure to the Mormon Pavilion are included in the Eastern States Mission Quarterly Historical Report, September 30, 1964, Manuscript History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; see also Staples, Scrapbook.

[56] Wilburn C. West, quoted in Richard J. Marshall, “The New York World’s Fair . . . A Progress Report,” Improvement Era, April 1965, 297.

[57] Kogan, “The Mormon Pavilion,” 51–52.

[58] Peterson, “History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions,” 115–17.

[59] David W. Evans, My Brother, Richard L., ed. Bruce B. Clark (Salt Lake City: Beatrice Cannon Evans, 1984), 75.

[60] Marshall, “A Final Report,” 1170.

[61] On August 19, 2014, Elder David A. Bednar, speaking at Campus Education Week at Brigham Young University, announced the film Meet the Mormons. In addition to announcing this most recent media endeavor, he called upon Latter-day Saints to utilize social media as a missionary tool. The full transcript of his address is found at https://

[62] Marshall, “A Progress Report,” 335.