“I Mean to Be Baptized for Scores More”: Baptisms for the Dead among the Latter-day Saints, 1846–67

Richard E. Bennett

Richard E. Bennett, “'I Mean to be Baptized for Scores more': Baptisms for the Dead among the Latter-day Saints, 1846–67,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 139–57.

Richard E. Bennett was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

Wilford Woodruff served as president of the St. George Temple, becoming the authorized catalyst for baptisms for the dead.

It is an honor to dedicate my chapter to the man who has published more books and articles documenting the history of modern-day Latter-day Saint temples than anyone else. From his well-received study Temples to Dot the Earth to his most recent work, The Oakland Temple: Portal to Eternity, historian Richard Cowan truly is ‘Mr. Temple’ to all who know him well. As much as he has devoted his career of fifty-three years to excellent teaching in the classroom, he has equally enjoyed writing on, speaking about, and visiting temples around the world—scores of them! In the process he has come to understand not only those things architectural, social, and historical in regards to temples, but also the deeper doctrinal matters of temple worship and how such have blessed and enriched the lives of countless thousands of believing Latter-day Saints. His passion for this sacred topic will ever remain an inspiration to me, one of his many disciples.

Well known in the history of Nauvoo was Joseph Smith’s initiation of vicarious salvific work for the dead, specifically baptisms for the dead.[1] Announced on August 15, 1840, at the funeral of Seymour Brunson, baptisms for the dead were first performed in the Mississippi River, often men for women and women for men in their enthusiasm for performing baptisms for deceased loved ones and friends. Later, on November 8, 1841, a temporary wooden baptismal font in the basement of the Nauvoo Temple was dedicated and on November 21, baptisms for the dead were conducted there under the direction of Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and John Taylor. Wrote Joseph Smith in his journal on December 20, 1841, “I baptized Sidney Rigdon in the font for and in behalf of his parents; also baptized Reynolds Cahoon and others.”[2] Susan Easton Black and Harvey Black, in their comprehensive compilations, have shown that between 1841 and 1845, a minimum of 11,530 baptisms for the dead were performed in the river and in the temple at Nauvoo.[3]

Decline in Baptisms for the Dead

In sharp contrast to the large number of baptisms for the dead performed in Nauvoo between 1841 and 1845, was their virtual disappearance among the Latter-day Saints between 1846 and 1867. Save for Wilford Woodruff’s performing this ordinance for a handful of people at Winter Quarters, one other in City Creek in August 1855, two in 1857, and a handful in 1865 and 1866, this ordinance was not on the Mormon celestial radar scope until 1867.[4] It was as if the practice had gone into a long desert hibernation.[5]

The emphasis among the early settlers in Deseret was not on baptisms for the dead, but rather on rebaptisms of the living or “covenant baptisms,” which began in their new valley home on August 6, 1847, at City Creek with Brigham Young rebaptizing other members of the Twelve and Heber C. Kimball rebaptizing Brigham Young. Of the over 4,000 baptisms performed between 1847 and 1852, approximately 75 percent were rebaptisms.[6] Not only were all hands needed in the fields and in assisting emigrants in crossing the plains, but Brigham Young insisted on recovenanting the faithful in their new Zion by having everyone, himself included, rebaptized for the remission of their sins. Convert baptisms and baptisms for the healing of the sick and the restoration of health were also frequently performed.[7]

Need for a Sacred Location

A strong sentiment prevailed among most in the Quorum of the Twelve for restricting ordinances for the dead to the temple, or at least a “temple pro tem,” and baptisms for the dead to a specially constructed font dedicated for such purposes. At Winter Quarters in the early fall of 1846, Brigham Young said that “the use of the Lord’s house is to attend to the ordinances of the Kingdom therein; and if it were lawful and right to administer these ordinances out of doors where would be the necessity of building a house? We would recommend to the brethren to let those things you refer to, dwell in the temple, until another house is built.”[8]

Joseph Young of the Seventy seconded his brother’s sentiments when he said in conference in 1852: “There are other things [than living endowments] that never will [be performed] until the temple is built—of which are the baptism for the dead and our endowments by proxy for our dead friends. Are they going on? No. Will they before the house is built? No, not that I know of.”[9]

Orson Pratt was even more specific: “There are certain appointed places for the ministration of these holy ordinances. Temples must be built. . . . But in what apartments in the temple shall the baptism for the dead be administered? It will be in the proper place—in the lowest story or department of the house of God. Why: Because it must be in a place underneath where the living assemble, in representation of the dead that are laid down in the grave, . . . and in such a font this sacred and holy ordinance must be administered by the servants of God.”[10]

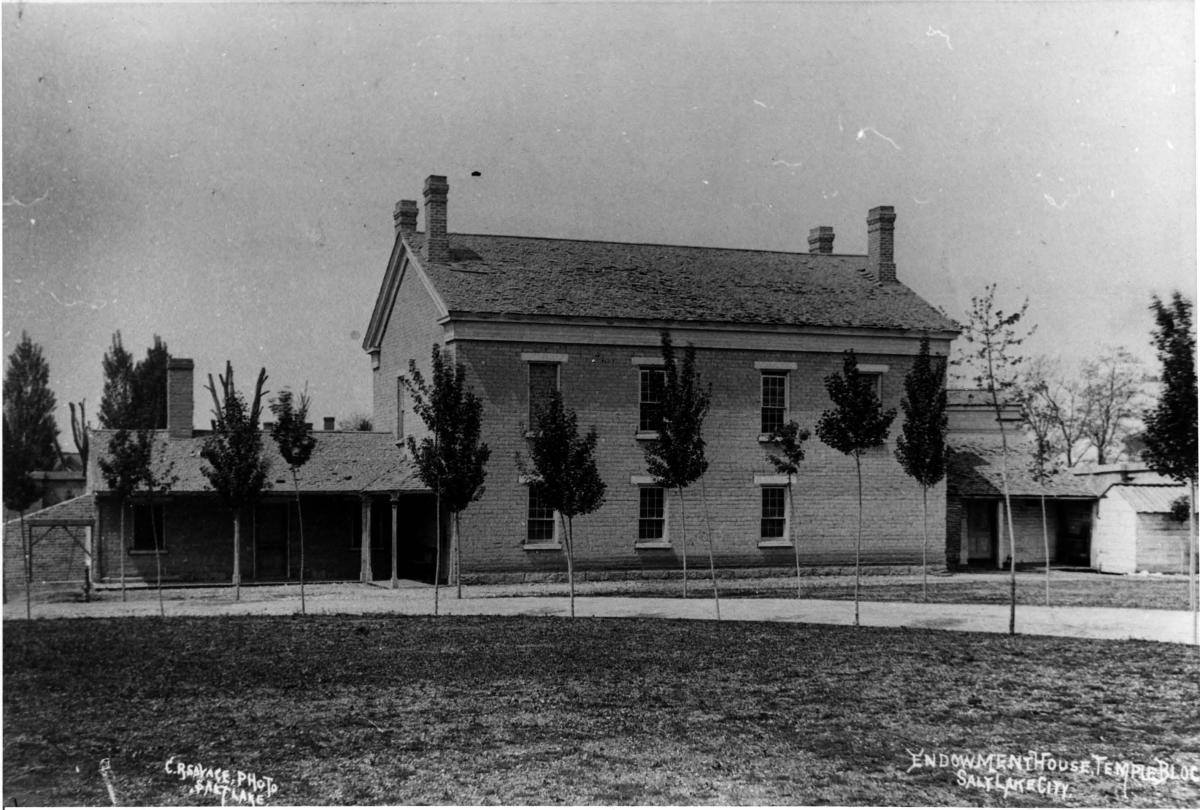

The font, therefore, was more than a metaphor. As perhaps the most unique and holy place and often separately dedicated from the temple itself, the font or “fountain,” to borrow William Marks’ terminology, laid claim to the performance of all baptisms for the dead.[11] As early as 1851, Brigham Young planned on erecting a font on Temple Square. “The President directed Truman O. Angell to get up a font for the baptisms for the dead on the temple block and another font to be baptized in for sickness.”[12] When the Salt Lake Endowment House was completed in 1855, it featured an outdoor stone font dedicated on October 1, 1856. An indoor wooden font (9½ by 12 feet) with two dressing rooms attached was dedicated in 1864 to replace the first font, which suffered from defective workmanship. It would appear, however, that though Brigham Young dedicated it “unto God for baptisms for the remission of sins[,] for the healing of the sick and for the baptism(s) for the dead,” this font was used primarily, if not exclusively, for baptisms and rebaptisms of the living until 1867.[13]

The Salt Lake Endowment House was completed in 1855 and was used primarily for baptisms and rebaptisms of the living until 1867. (Photo by Carles Roscoe Savage, courtesy of Church History Library.)

The Salt Lake Endowment House was completed in 1855 and was used primarily for baptisms and rebaptisms of the living until 1867. (Photo by Carles Roscoe Savage, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Lack of Reliable Records

Another reason few baptisms for the dead were performed was that there was an insufficient number of trusted family genealogies and other reliable ancestral records. Parley P. Pratt alluded to this deficiency in conference in April 1853: “Our fathers have forgotten to hand down to us their genealogy. They have not felt sufficient interest to transmit us their names, and the time and place of birth, and in many instances they have not taught us when and where ourselves were born, or who were our grandparents, and their ancestry.” Blaming it all on that “veil of blindness” cast over the earth in the form of the apostasy, Pratt went on to lament the lack of a “sacred archives of antiquity” with the resultant lack of knowledge of “the eternal kindred ties, relationship or mutual interests of eternity” and that the “spirit and power of Elijah” had only begun “to kindle in our bosoms that glow of eternal affection which lay dormant” for so many centuries. “Suppose our temple was ready?” he asked. “We could only act for those whose names are known to us. And these are few with most of us Americans. And why is this? We have never had time to look to the heavens, or to the past, or to the future, so busy have we been with the things of the earth. We have hardly had time to think of ourselves, to say nothing of our fathers.”[14] Thus they did as many baptisms as their immediate memories and available records allowed.[15]

Speaking some twenty-three years later, Wilford Woodruff, later founder of the Utah Genealogical Society, spoke of this same impediment to temple work for the dead, although by then in more encouraging terms:

If there is anything I desire to live for on this earth, or that I have desired, it has been to get a record of the genealogy of my fathers, that I might do something for them before I go hence into the spirit world. Until within a few years past, it has seemed as if every avenue has been closed to obtaining such records; but the Lord has moved upon the inhabitants of this nation and thousands of them are now laboring to trace [their] genealogical descent. . . . Their lineages are coming to light, and we are gradually obtaining access to them, and by this means we shall be enabled to do something towards the salvation of our dead.[16]

In their rush to leave Nauvoo, the Saints brought more tools than they did records, and this may have been the primary reason Brigham Young pointed repeatedly to the Millennium for such work to be done, a time when the needed records would be revealed. He said in private at Winter Quarters in early 1848, “We had the promise to have something if we built the temple in Nauvoo—we have now the privilege of acting for our dead; we have grandparents and ancestors whom we have to act for—it can’t be done in five or ten years—we can get our own ordinances and as many of our ancestors as we can—this will have to be done in the millennium by saviors who will be on Mount Zion, . . . pillars in the temple of our God.”[17]

The eventual solution to the problem of the scarcity and incorrectness of human records would be revelation of a most unusual kind: “About the time that the temples of the Lord will be built and Zion is established,” said Brigham Young in 1852,

There will be strangers in your midst, walking with you, talking with you; they will enter your houses and eat and drink with you, go to meeting with you and begin to open your minds as the Savior did the two disciples who walked out in the country in days of old. . . .

They will then open your minds and tell you principles of the resurrection of the dead and how to save your friends. . . . You have got your temples ready: now go forth and be baptized for those good people. . . .

Before this work is finished, a great many of the Elders in Israel in Mt. Zion will become pillars in the temples of God to go no more out and [will] . . . say—“Somebody came into the temple last night ;we did not know who he was, but he gave us the names of a great many of our forefathers that are not on record, and he gave me my true lineage and the names of my forefathers for hundreds of years back. He said to me . . . take them and write them down, and be baptized and confirmed . . . and receive of the blessings of the eternal priesthood for such and such an individual, as you do for yourselves.[18]

Until such a time, baptisms for the dead were rarely performed.

It is true that there were other scattered and isolated references in our time period of study (1846–67) to baptisms for the dead, such as the following injunction given to Addison Pratt before his return as a missionary to the islands of the South Pacific: “When you get to [the] Islands build a tabernacle for baptizing for the dead and for the endowments for the Aaronic P[riesthood].”[19] But so far as is yet known, no such ordinances were ever performed there.

Reinstitution of Baptisms for the Dead

Thus it was that baptisms for the dead lay moribund for twenty-one years. Then, for reasons yet to be fully determined, the ordinance was gradually reinstituted, starting once again with Wilford Woodruff leading the charge. On June 14, 1867, Woodruff was baptized by George Q. Cannon for his father, Aphek Woodruff, who had died six year before. He was afterwards confirmed by President Brigham Young. Immediately following, his wife Phebe Carter Woodruff was baptized by George Q. Cannon for Wilford’s stepmother, Azubah Hart Woodruff (d. 1851), and confirmed by Brigham Young. Ten more such ordinances were performed in June, all in the Endowment House on the northwest corner of the present Temple Square in Salt Lake City, an edifice that had featured a baptismal font since 1855. During 1867, 92 baptisms for the dead were conducted. The corresponding number for 1868 was 432.[20]

A close examination of the 524 deceased persons for whom baptisms were performed in 1867 and 1868 reveals something of the nature of the practice. The great majority of these proxies were older, like the Woodruffs, and were baptized for deceased children, siblings, grandchildren, and nieces and nephews. It was more for their descendants and less for their ancestors, more for the immediate generation than for the past (see figure 1).

|

Figure 1. Nature of Relations, 1867 and 1868 93 Sons and daughters (deceased) 75 Brothers and sisters 63 Grandchildren 79 Nieces and nephews 38 Sons- and daughters-in-law 21 Brothers- and sisters-in-law 44 Cousins 4 Grandparents 19 Great-grandchildren 52 Friends 12 Parents and stepparents Notes: · Far more descendants than parents/ · 10 percent were friends; 90 percent were family · None more than four generations back |

Fifty-two out of 523, or 10 percent, were for “friends” and not family members. Such figures would indicate that the revival of baptisms for the dead was a “family-driven” initiative, not a Churchwide decree, and that the memory of the living—in these cases for immediate families and close friends—served as substitutes for records.[21]

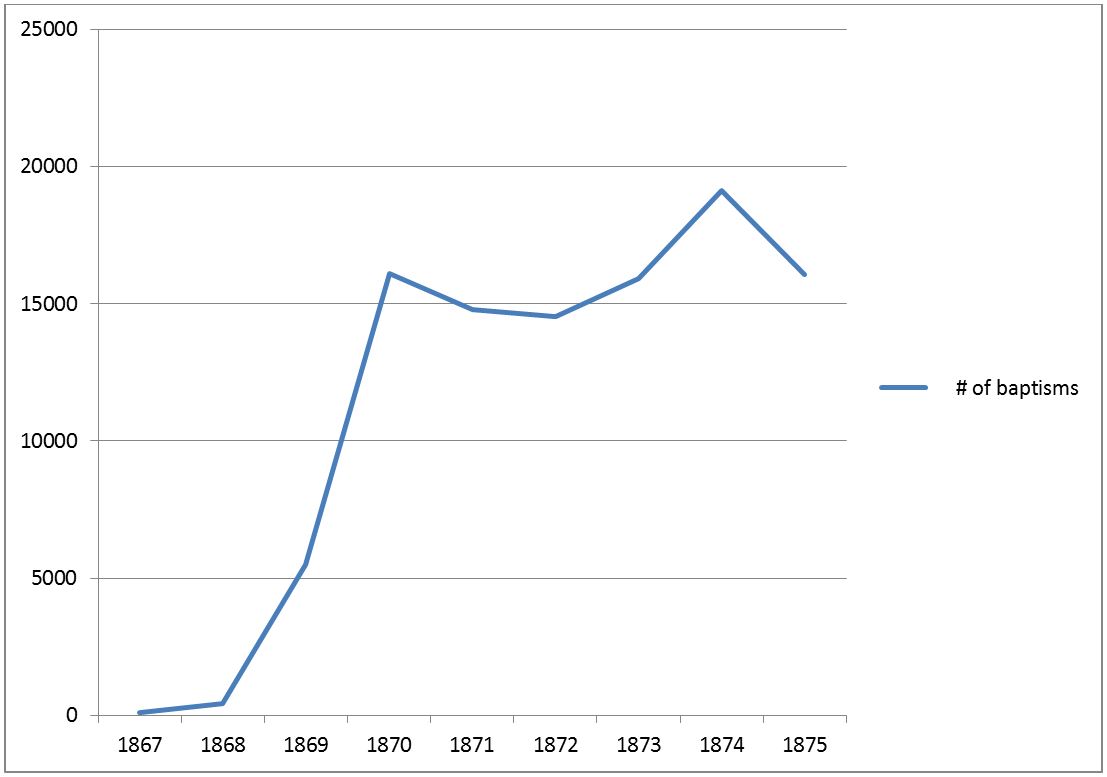

All that changed dramatically, however, beginning in June 1869, when 582 baptisms were performed, more than all of 1867 and 1868 combined. The year 1869 saw a grand total of 5,503 such ordinances in what was clearly a turning point for work for the dead in modern Church history. Note the following figures: in 1870, 16,082 baptisms; in 1871, 14,770 baptisms; in 1872, 14,516 baptisms; and in 1875, 16,047 baptisms (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of Baptisms for the Dead Performed in Salt Lake Endowment House, 1867-75

Figure 2. Number of Baptisms for the Dead Performed in Salt Lake Endowment House, 1867-75

Why the Sudden Increase in Baptisms for the Dead?

What accounts for this renewal of the practice in the desert? As already indicated, the Saints had been using the baptismal font in the Endowment House for living baptisms, adoptions, and baptisms for health for a dozen years. Between 1855 and 1867 the population of Salt Lake City had grown to approximately twelve thousand, with new convert emigrants arriving by the thousands every year. True, Brigham Young had other concerns, such as colonization, missionary work, and the Utah War, but something was stirring in the late 1860s—what was it?

At least five possible factors demand our attention. Some are purely speculative and highly debatable; others more substantive and supportable. Until more information is forthcoming, one can only offer them as possible explanations to what is yet an unanswerable. I will list them in ascending order of possibility. They are (1) the ending of the Civil War, (2) the coming of the railroad, (3) the Godbeite movement, (4) the securing and availability of more accurate genealogical records, and (5) the influence of Wilford Woodruff.

The ending of the Civil War.

Speaking in 1861, Brigham Young in reference to the War saw the Lord’s hand in preparing their return to Jackson County through the medium of the Civil War. “Just as soon as the Latter-day Saints are ready and prepared to return to Independence, Jackson County, in the state of Missouri,” he said, “just as soon will the voice of the Lord be heard. ‘Arise now, Israel, and make your way to the center stake of Zion’ . . . Do you believe that we, as Latter-day Saints, are preparing our own hearts—our own lives—to return to take possession of the center stake of Zion, as fast as the Lord is preparing [it]? . . . We must be pure to be prepared to build up Zion. To all appearance the Lord is preparing that end of the route faster than we are preparing ourselves to go.”[22]

The following year, 1862, with the war intensifying, Brigham Young referred to the frustratingly slow construction of the Salt Lake Temple and predicted the Latter-day Saints would return to Missouri in 1869. “I am afraid we shall not get it up until we have to go back to Jackson County which I expect will be in seven years. I do not want to quite finish this Temple for there will not be any temple finished until the one is finished in Jackson Co. [as] pointed out by Joseph Smith. Keep this as a secret to yourselves, lest some may be discouraged.”[23] This concept of not finishing the temple, and with it the postponement of temple work for the dead, might have pointed to Brigham Young’s consistent reticence toward embarking wholeheartedly on work for the dead without a temple first being constructed in their midst.

At the end of 1863, with the war at fever pitch, a watchful Wilford Woodruff had also concluded that this might be the long-awaited time of return. “The Lord is watching over the interests of Zion and sustains his Kingdom upon the earth and [is] preparing the way for the return of his Saints to Jackson County, Missouri, to build up the waste places of Zion. Jackson County has been entirely cleared of its inhabitants during the year 1863 which is one of the greatest miracles manifested in our day and those who have driven the Saints out and spoiled them are in their turn now driven out and spoiled.”[24]

However, at long last, America’s deadliest war ended at Appomattox in April 1865, and with the waning of the war, Mormon statements about the conflict also lessened. The news of Lee’s surrender was happily received in Utah, although celebrations were muted by the reflection on the destruction of the South, Sherman’s march through Georgia, and the horror and devastation of the past four years. The end of the Civil War signaled a sense that a return to Jackson County, at least imminently, was not in the cards. Instead, Zion would stay in the West, at least for now, with all its attendant ordinances. Temples would have to be built and with them, redemption of the dead must would not be postponed any longer. Construction of the St. George Temple was first announced just five years after the ending of the war.

The transcontinental railroad.

A second consideration is that of the coming of the railroad and with it the end of Mormonism’s era of “splendid isolation” far away in the West. Granted, there is yet no concrete evidence tying baptisms for the dead to the railroad; however, it must be noted that the first real spike in the numbers of baptisms for the dead came in June 1869 when 582 such ordinances were performed, just a month after the May 10 completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point some one hundred miles away from Temple Square.[25] Well known in Mormon history is the fact that the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Retrenchment Societies were then organized on a Churchwide basis to protect the youth from the evil “Gentile” influences of the East now coming down the track in the form of new fashions, forms of entertainment, educational philosophies, illicit behaviors, and a trainload of other “worldly” influences. So, too, did Brigham Young revitalize a moribund Relief Society on a Churchwide basis to provide a greater role and voice for female Latter-day Saints in anticipation of the coming cultural, intellectual, and religious tensions that the railroad was bound to foster. One might make a reasonable argument that even the establishment of Church schools and academies were, at least in part, established in anticipation of the coming new social order, a sea change in Mormon society. The point is that increased attention to temple-related ordinances and covenants would contribute to a sense of a covenant people.

The Godbeite apostasy

A third possible factor was the Godbeite apostasy of the late 1860s and 1870s. An intellectual dissenting movement led by William S. Godbe that flowered in 1869, Godbeism was a movement of such liberal-minded dissenters as T. B. H. Stenhouse, George Watt (Brigham Young’s personal secretary), E. L. T. Harrison, Edward Tullidge, and Godbe himself, who devalued the Book of Mormon and the Doctrine and Covenants, rejected a personal deity, disputed the Resurrection and the Atonement of Christ, and opposed the economic policies and overall leadership of Brigham Young. They formed their own church with apostles, including Amasa Lyman, who also went over to this their cause. Some of its leaders later went on to found the Salt Lake Tribune.[26]

Central to the Godbeite movement was its belief in spiritualism and communication with the dead through séances, so-called “automatic writings” or written communications with the deceased, ectoplasm, and all the paraphernalia of the paranormal. Spiritualism had erupted with the Fox sisters in Rochester, New York, not far from Palmyra, back in 1848 and had mushroomed in popularity in the wake of so many untimely deaths brought on by the Civil War. Spiritualism, with its outreach to the spirits of the dead, brought closure to many whose sons, brothers, and fathers had died, often in lonely agony and pain, far away from home. Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, would later do much to popularize this pseudo-religion during and immediately after World War I.[27]

Since at least 1853 when the cornerstone of the Salt Lake Temple was laid, Church authorities have had been well aware of what they eventually saw as a counterfeit movement and taught had warned against as its parallels to temple ordinances. Warned Wrote Parley P. Pratt, “The Saints must learn to discriminate between the lawful and the unlawful mediums or channels of communication—between the holy and impure, the truths and falsehoods thus communicated.”[28]

Without denying the possibility of communing with the dead, Church leaders increasingly warned against “the doings of the Spirit Rappers” and that such manifestations were a tool of the devil. Warned Brigham Young in 1870, “Take all who are called spiritualists and see if they can produce the order that is in the midst of this people. Here are system, order, organization, law, rule and facts. Now see if they can produce any of these features. They cannot. Why? Because their system is from beneath, while ours is perfect and is from above; one is from God, the other is from the devil that is all the difference.”[29] Their point was that spiritualism spoke of and to the dead, whereas vicarious temple work was not communion with but salvation for the dead. One was yearningly inquisitive; the other satisfyingly redemptive and based upon scripture, and under no circumstances were the two to be equated.

By October 1869, the Godbeite movement was in full force with its leaders being excommunicated for apostasy and their “reform” movement in acceleration mode. And though the movement floundered soon afterwards as a formal institution, since its spiritualistic theology and liberal economics had little lasting appeal among the mainstream Latter-day Saints, its sudden rise certainly paralleled the rebirth of baptisms for the dead.

Was the reinstitution of baptisms for the dead in the late 1860s in some way an effort to blunt the spiritualist movement? The connection is admittedly tenuous; however, the late well-known Mormon scholar T. Edgar Lyon thought so. In a biography of his ancestor John Lyon, he wrote: “Beginning in 1867 and continuing through 1869, Lyon and his family conducted a spiritual campaign to baptize their dead ancestors. This may have served as a counter to the Godbeites, who argued that the Church had become too materialistic and had departed from its earlier spiritual manifestations.”[30]

Greater access to genealogical records

A fourth factor was the increased number of genealogical records, or the greater availability of more accurate ancestral records. Reference has already been made to the concern of Church leaders in the 1850s of the impeding nature of the lack of reliable genealogical source material. However, the Civil War sparked a rise, at least in America, of genealogical societies and the importance of keeping more accurate documents. The Deseret Evening News noted this trend in 1875 when it reported, “The rapidly growing interest in genealogy and family history is shown in the fact that 359 genealogical works have appeared in the United States since 1860.”[31] With the coming of the railroad and of the telegraph, access to more accurate information was rapidly becoming a reality, if not a godsend, to genealogical research. The railroad greatly expedited mail deliveries throughout the land and facilitated genealogical research as never before. As one female member of the Church noted, “All the good brethren and sisters have been doing their best to get out their relations, . . . and I know many of them who have set over to England and have spent large sums of money in tracing their pedigrees and genealogies, in order to find out the right names to be baptized as proxies for the dead who owned those names. I have been baptized for a good many of my own relations, and I mean to be baptized for scores more.”[32] In much the same way that twenty-first-century genealogical research has greatly benefitted from the arrival of the electronic age, so it began to stir to the sound of the iron horse, a harbinger of much better things to come. Observing this trend, Brigham Young remarked in 1872, “We are now baptizing for the dead and we are sealing for the dead, . . . the history of whom we are now getting from our friends in the east. The Lord is stirring up the hearts of many there and there is a perfect mania with some to trace their genealogies and to get up printed records of their ancestors.”[33]

Influence of Wilford Woodruff

A final consideration and possible explanation for the revival of baptisms for the dead was not a circumstance at all, but a person. By 1867, Wilford Woodruff had served as an Apostle for twenty-nine years. When he first heard of this doctrinal practice from Joseph Smith, he said it was like a “shaft of light from the throne of God” and “opened a field wide as eternity” to his mind.[34] He had already baptized a few people for their deceased relations at Winter Quarters. He did so again in Salt Lake City in 1853.[35] We have already noted that Wilford Woodruff was the first to be proxy baptized when the ordinance resumed in the Endowment House in 1867. Later, as president of the St. George Temple and the first temple president in Church history, H he was the authorized catalyst not only for baptisms for the dead but also for beginning the practice of endowments for the dead in the St. George Utah that temple beginning in January 1877.[36] Woodruff would also be responsible for the ending of the law of adoption, a temple-related ordinance in which people and their families were sealed to prominent general authorities, not to their deceased ancestors.[37] In its place, he instituted the practice of living descendants being sealed to their deceased ancestors in a chain of sealed relationships as far back as the records would allow. Is it little wonder that modern temple work owes so much to him?[38]

The first real spike in the numbers of baptisms for the dead came in June 1869, just a month after the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, in Utah Territory. (Photo by Andrew Joseph Russell.)

The first real spike in the numbers of baptisms for the dead came in June 1869, just a month after the completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Point, in Utah Territory. (Photo by Andrew Joseph Russell.)

Conclusion

Just five years after the end of the Civil War, construction of the St. George Temple was announced. (Photo by Jesse E. Tye, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Just five years after the end of the Civil War, construction of the St. George Temple was announced. (Photo by Jesse E. Tye, courtesy of Church History Library.)

This paper has shown that between 1846 and 1867 the ordinance of baptism for the dead was barely practiced among the pioneer Latter-day Saints. A wide variety of temporal concerns were more pressing. All that began to change, however, in 1867 and by 1869, as this ordinance came back into practice. What explains this desert resuscitation is not yet fully known, although such factors as the ending of the Civil War, the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the Godbeite movement with its brand of spiritualism, and the availability of more accurate records all may have played a role. Nor can one dismiss the influence of Wilford Woodruff, one of the greatest record keepers in the history of the Church, and his yearning for the records and salvation of his ancestors. Whatever the cause, by 1870 the ordinance of baptism for the dead had been revived and has since become a staple of temple worship within The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[39]

Notes

[1] I wish to thank assistant Church historian Richard E. Turley Jr., Brandon Metcalf, and the staff of the Church History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, for their assistance in the researching of this paper. I wish also to express appreciation to Wendy Top, my research assistant, for her valued work on this paper. For a more expanded study of LDS temple work between 1846 and 1855 from which this work is derived, see my article entitled “‘The Upper Room’: The Nature and Development of Mormon Temple Work, 1846–1855,” in the Journal of Mormon History 2015.

[2] Joseph Smith, Manuscript History of the Church, 4:434, 437. As cited in Robert Bruce Flanders, Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1975), 98.

[3] Susan Easton Black and Harvey Bischoff Black, Annotated Records of Baptisms for the Dead, 1840–1845, Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois, 7 vols. (Provo, UT: Center for Family History and Genealogy, Brigham Young University, 2000), 1:viii–ix. See also M. Guy Bishop, “‘What has Become of Our Fathers’: Baptism for the Dead in Nauvoo,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23, no. 2 (Summer 1990): 95. Other baptisms for the dead were performed at Quincy, Illinois, and at Kirtland, Ohio. See Alexander L. Baugh, “‘For This Ordinance Belongeth to My House’: The Practice of Baptism for the Dead Outside the Nauvoo Temple,” Mormon Historical Studies 3, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 47–58.

[4] Lyrena Evan Moffitt was baptized by proxy in City Creek on August 21, 1855; two year later, on October 23, 1857, Nabby Howe and Nabby Young were similarly baptized. That same month, Church Historian’s Office clerks Leo Hawkins and Richard Bently were busy “setting up” records of baptisms for the dead. Historian’s Office Journal, 23 and 24, October 1857, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (also available online at http://

[5] Endowment House Baptism for the Dead Record Book, CR 334 8, book A, 1–12, A–G, Church History Library. These cover entries for 1867 and 1868. Note: In the 1868 entries, there are notations for earlier baptisms that were done in August–October of 1866 and again sometime in 1865.

[6]“Rebaptisms,” Record Book, Salt Lake Stake, CR 604 78, Church History Library, used with permission. “Covenant baptisms” were rebaptisms for the remission of sins, an ordinance for recommitment to the faith. They continued into the early twentieth century. For a good introductory study on this topic, see D. Michael Quinn, “The Practice of Rebaptism at Nauvoo,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (Winter 1978): 226–32.

[7] Kristine L. Wright and Jonathan A. Stapley, “‘They Shall Be Made Whole’: A History of Baptism for Health,” Journal of Mormon History 34, no. 4 (Fall 2008): 83–88.

[8] Brigham Young to George Miller, September 20, 1846, Brigham Young Papers, Church History Library.

[9] Joseph Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1881), 6:242.

[10] Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 29:647–48.

[11] William Marks, former Nauvoo stake president, did not go west with the Latter-day Saints; rather, he stayed back and went on to serve in the First Presidency of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints under President Joseph Smith III. In May 1865, in a council meeting of the presidency, Marks said, “When Joseph [Smith] stopped the baptism for the dead he stated that he did not believe it would be practiced any more until there was a fountain built in Zion or Jerusalem.” RLDS Council Minutes, May 1865, Archives of the Community of Christ, Independence, Missouri.

[12] Historian’s Office Journal, December 7, 1851. I wish to thank Randall Dixon for this and related references.

[13] See Church Historian’s Office Journal, October 2, 1856, and September 2, 1861; see also Wilford Woodruff’s, Journal, 1833–1898 Typescript, ed. Scott G. Kenney (Midvale, Utah: Signature Books, 1983), June 4, 1864, 6:173; Church Historian’s Office Journal, December 30, 1856. In speaking of this event, Brigham Young wrote, “It is expected this font will also be used for baptizing for the dead.” Brigham Young to Salia Smith, October 4, 1856, Brigham Young Letterpress Copybooks, Church History Library.

[14] Parley P. Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 1:13 (April 7, 1853).

[15] A related concern was that of accurate record keeping. As commanded in section 128, careful records of all such baptisms for the dead had to be kept. Glen M. Leonard, in his study of Nauvoo, writes that when Joseph Smith discovered, in the fall of 1842, an “inconsistent pattern” in the records of proxy baptisms, he explained that the “record itself had legal standing in the next life and therefore had to be accurately presented and preserved.” Glen M. Leonard, Nauvoo: A Place of Peace, A People of Promise, (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2002), 238.

[16] Wilford Woodruff, in Journal of Discourses, 18:191.

[17] General Church Minutes, Church Historian’s Office, CR 100 318 box 2 folder 2, 13 February–31 March 1848, Church History Library. Again, in 1854, he declared: “As I have frequently told you, [salvation of the dead] is the work of the Millennium. It is the work that has to be performed by the seed of Abraham, the chosen seed, the royal seed, the blessed of the Lord.” Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 2:138 (December 3, 1854).

[18] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 6:294–95 (August 15, 1852).

[19] General Church Minutes, Church Historian’s Office, April 8, 1849, CR 100 318, box 2, folder 10.

[20] Endowment House Baptism for the Dead Record Books, Book A, 1–12, Church History Library. Note particularly the insertions after entries for April 14, 1869. See also Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:348, June 14, 1867.

[21] No records of a genealogical library or archive of the records of those baptized in the Endowment House have yet been located.

[22] Brigham Young, in Journal History of the Church, July 28, 1861, Church History Library.

[23] Brigham Young, in Journal History of the Church, August 22, 1962. See also Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:71, August 23, 1862.

[24] Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 6:147, (January 1, 1864); also cited in Journal History of the Church.

[25] The number of baptisms for the dead in 1867 was 92; for 1868, 432. For the entire year of 1869, the corresponding number was 5,506. Clearly 1869 was the turning point year for this ordinance.

[26] For the most comprehensive study of the Godbeite movement, see Ronald W. Walker’s highly readable Wayward Saints: The Godbeites and Brigham Young (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

[27] Arthur Conan Doyle, The Sir Arthur Conan Doyle Reader: From Sherlock Holmes to Spiritualism (New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002).

[28] Parley P. Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, 2:44 (April 6, 1853). See also Michael W. Homer, “Spiritualism and Mormonism: Some Thoughts on Similarities and Difference,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 21, no. 1 (Spring 1994): 171–91.

[29] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 13:266 (October 6, 1870). See also Homer, “Spiritualism and Mormonism,” 181.

[30] T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1989), 174. Lyon’s account of his ancestors being heavily involved in early baptisms for the dead is well verified by the records themselves.

[31] Deseret Evening News, November 5, 1875.

[32] Fanny Stenhouse, Tell It All: The Story of a Life’s Experience in Mormonism (Hartford, CT: A. D. Worthington and Co. Publishing, 1875), 490–91.

[33] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 15:138.

[34] Wilford Woodruff remarks made at the Salt Lake Stake Conference, December 29, 1897. Deseret Weekly, December 25, 1897.

[35] Endowment House Baptism for the Dead Record Book, CR 334 8, book A, 1–12, A–G, Church History Library.

[36] See the author’s article entitled “‘Line upon Line, Precept upon Precept’: Reflections on the 1877 Commencement of the Performance of Endowments and Sealings for the Dead,” BYU Studies 44, no. 3 (2005): 38–77.

[37] From 1846 until 1893, many members of the Church were sealed to General Authorities who were known to be faithful priesthood holders and often holders of the keys of the priesthood. Only gradually did the doctrine become clear that deceased ancestors were being taught the gospel in the spirit world and could receive the full blessings of Church membership. President Woodruff ended the law of adoption in 1893. For more on the law of adoption, see Gordon Irving, “The Law of Adoption: One Phase of the Development of the Mormon Concept of Salvation, 1830–1900,” BYU Studies 14 (Spring 1974): 291–314.

[38] The definitive biography of Wilford Woodruff remains Thomas G. Alexander, Things in Heaven and on Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993). For a well-researched, largely uncritical, yet ambitious new study, see Jennifer Ann Mackley, Wilford Woodruff’s Witness of the Development of Temple Doctrine (Seattle: High Desert Publishing, 2014).

[39] The numbers of baptisms for the dead performed in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City after 1869 were as follows:

1870: 16,083

1871: 14,770

1872: 14,516

1873: 15,926

1874: 19,119

1875: 16,047

Endowment House Baptism for the Dead Record Books, CR 334 8, books A–F, Church History Library.