How the King James Translators “Replenished” the Earth

Kent P. Jackson

Kent P. Jackson, “How the King James Translators 'Replenished' the Earth,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 295–303.

Kent P. Jackson was a professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this article was written.

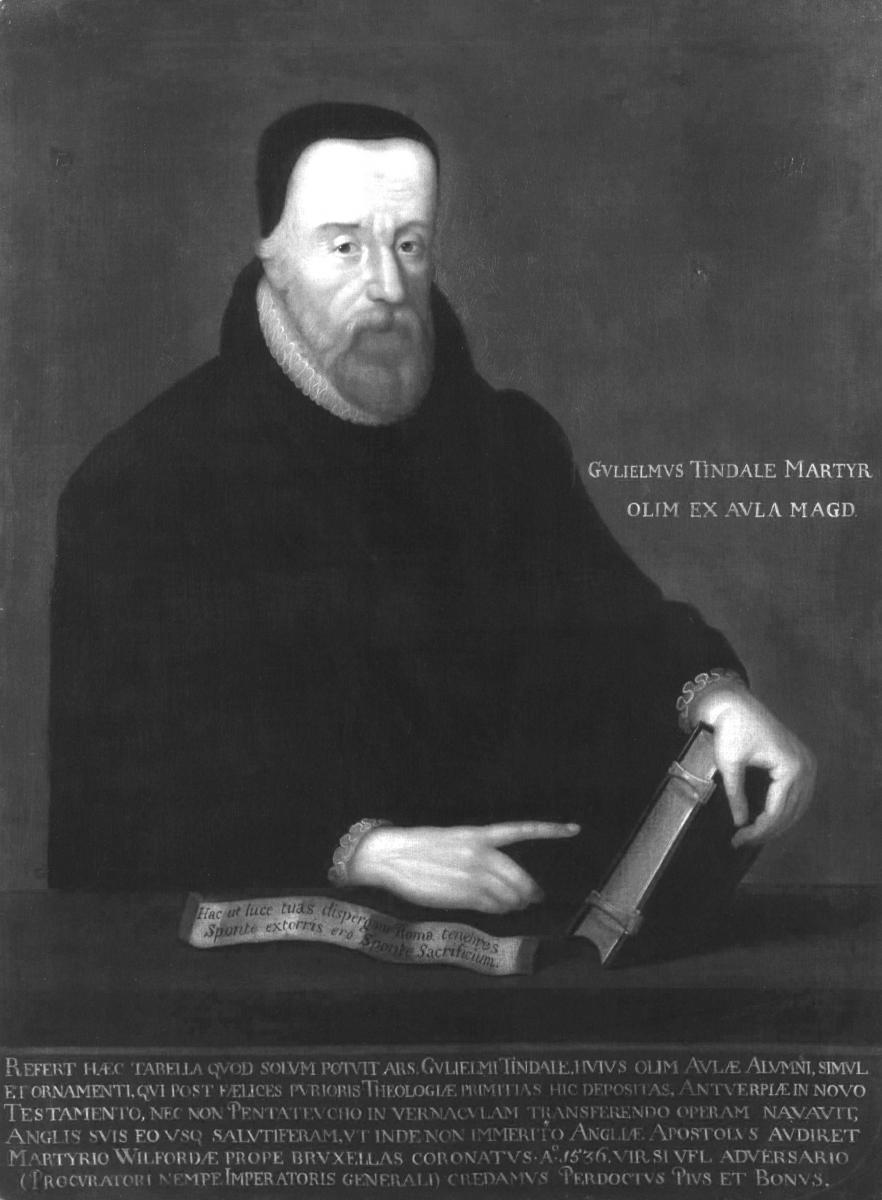

William Tyndale, translator of the Bible. (National Portrait Gallery, London.)

William Tyndale, translator of the Bible. (National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Richard Cowan and I met in August 1980, and we have been close friends since then. He was one of my earliest and best mentors. At his instigation, I was called to the Church’s writing committee for the Gospel Doctrine curriculum, on which he and I served together for eight years. Richard and I have spent many days together on the road, traveling to Church history sites both in the United States and in Europe. We spoke together at a fireside in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1987. One of our favorite associations over the years has been a special private lunch meeting the two of us have each June to discuss and analyze the new Area Presidency assignments. Richard’s keen eye for how the Church is administered has taught me many things, the most important of which being that he and I can’t predict anything very well.

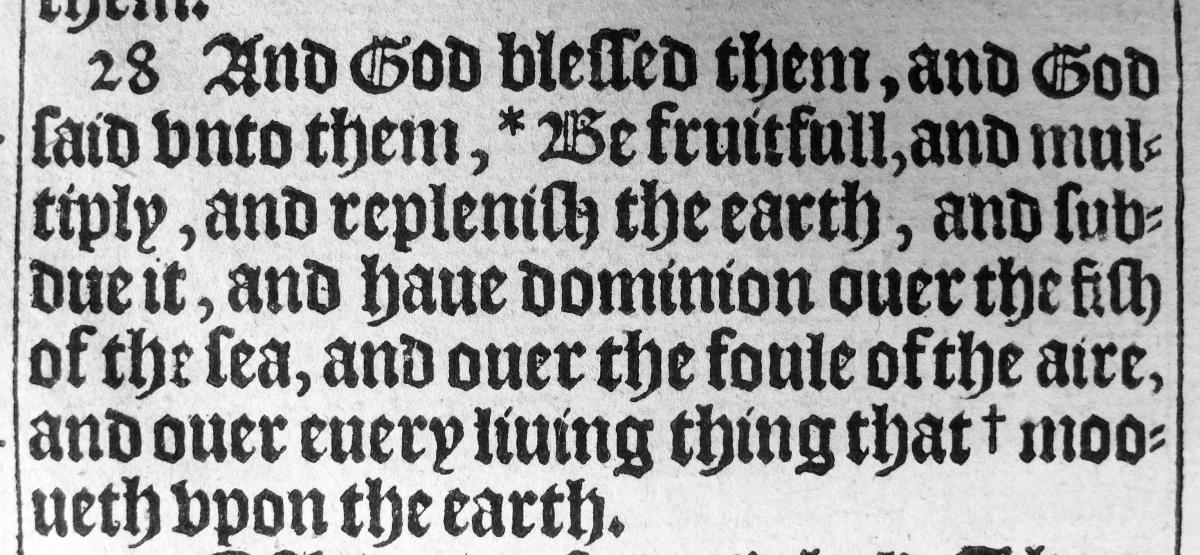

When God first created humans, he commanded them, pĕrû ûrĕbû ûmil’û et-hā’āreṣ: “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth” (Genesis 1:28). The King James translation, however, uses the word replenish in this verse to represent the Hebrew word for “fill.” It also uses replenish at Genesis 9:1, where Noah and his children are told in the same words, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the earth.” The Hebrew verb has the meaning “fill” throughout the Old Testament, and in almost all other instances in the King James Bible, the translators rendered it with fill. So why did they choose the word replenish at Genesis 1:28 and 9:1? The answer is found in the basic history of why there is a King James translation and what it was originally intended to be.

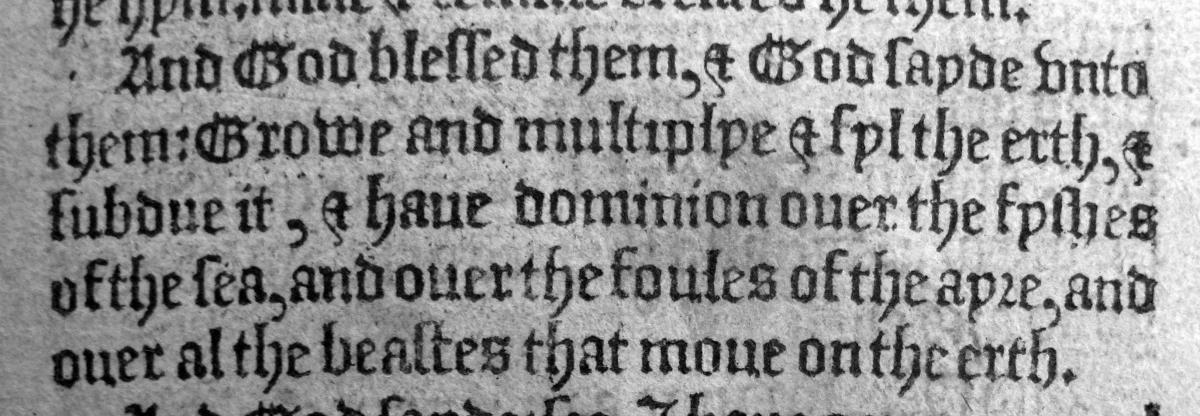

King James translation, 1611, Genesis 1:28: "Be fruitfull, and multiply, and replenish the earth." (All photos courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

King James translation, 1611, Genesis 1:28: "Be fruitfull, and multiply, and replenish the earth." (All photos courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

The 1611 King James Bible advertised itself as “newly translated out of the original tongues: & with the former translations diligently compared and revised.”[1] In reality, however, it was the other way around. It was a revision of the previous English translation, with comparisons to the texts in the original languages and earlier translations.

The father of the English Bible was William Tyndale (d. 1536).[2] Using editions of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament that only recently had appeared in print, he produced the first English translation of the Bible from its original languages. His goal was to make the Bible so accessible that every plowboy in England could own and read a copy. This meant that his Bibles were small and relatively inexpensive but also that they were in English that common people could read and understand. His word choices reflect what Nephi called “plainness” (2 Nephi 25:4)—clear and simple language that is deliberately free of pomp and elegance. His translation was “accessible, useful, clarifying, less interested in the grandeur of its music than the light it brings.”[3] Tyndale’s words have endured. Research has shown that over 75 percent of the King James Old Testament (of the sections he translated) comes from Tyndale, as well as over 80 percent of the King James New Testament.[4] During the 1520s and 1530s, he translated and published all of the New Testament, Genesis to Deuteronomy, and Jonah. He probably also translated Joshua to 2 Chronicles, books that were published by someone else after his death.[5]

Other English Bible translations followed in succession, and all were to a large extent revisions of Tyndale’s. These include the Bibles of Myles Coverdale, John Rogers (under the pseudonym of Thomas Matthew), and the Great Bible (produced by Coverdale and others). Then came the Geneva Bible, which was translated and printed by exiled reformers who had fled to Protestant Switzerland in order to avoid persecution in Catholic-ruled Britain. The Geneva Bible was a very good translation, and it was published with an extensive collection of useful materials for readers—maps, illustrations, cross references, study helps, and expansive explanatory notes. When England became permanently Protestant, the Geneva Bible became the English Bible of choice.

But for the authorities in England, the Geneva Bible was a problem. It was produced by Puritans independently of the crown and the Church of England, and the marginal notes contained material that displeased both. An official version was needed to replace it, and so in a short time, the church created the Bishops’ Bible. It was not a success. The words and language in the Bishops’ Bible suggest that the conservative clerics who created it were not altogether comfortable with the idea of giving ordinary people free access to the word of God. Distancing the text from its readers, they produced a translation removed from the language of common people. In its vocabulary and sentence structure, it was a throwback to earlier times, with an increase of less-familiar Latin-based words and much Latin-based syntax. It never caught on. People found it unappealing, bought few copies of it, and continued to buy the Geneva Bible instead. In time, it became apparent to King James I and others that a better official translation was needed.

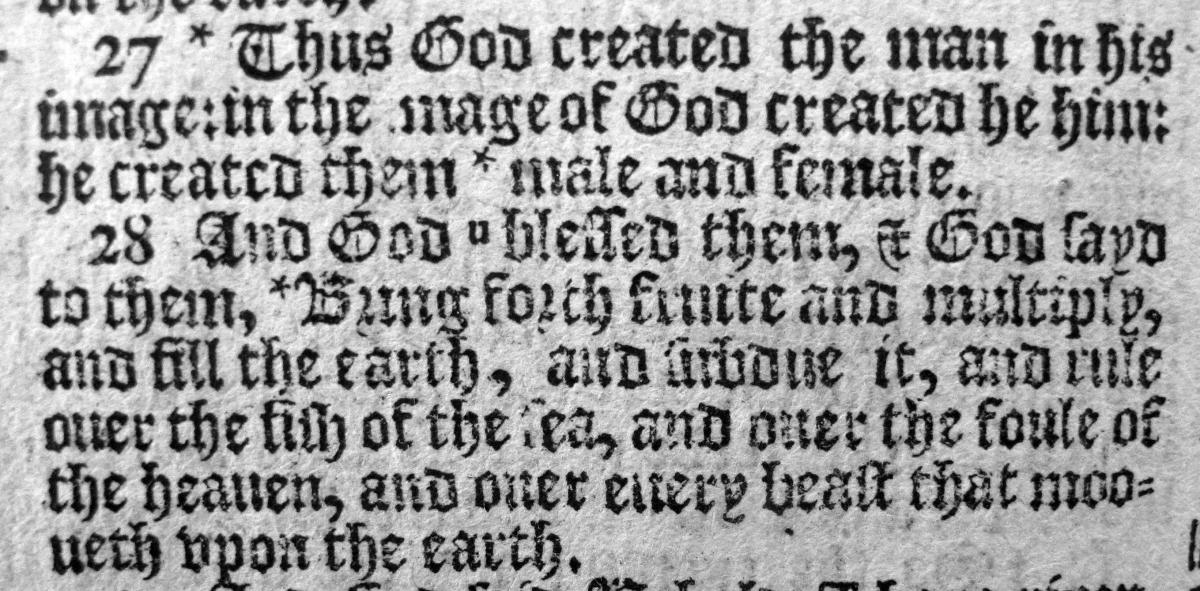

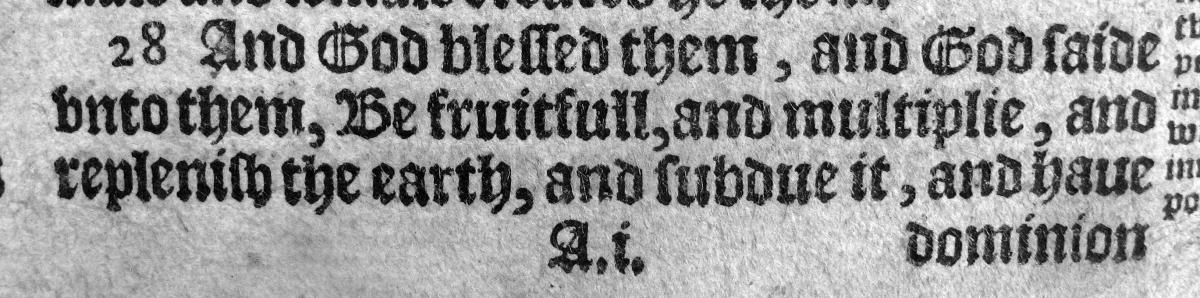

Geneva Bible, 1594, Genesis 1:28: "Bring forth fruit and multiply, and fill the earth."

Geneva Bible, 1594, Genesis 1:28: "Bring forth fruit and multiply, and fill the earth."

That would be the King James Version.[6] King James put in place a translating committee of about fifty men, all but one of whom were bishops or priests of the Church of England. Fortunately, among them were the best Hebrew and Greek scholars in Britain. The translators’ primary instruction was to make a revision of the Bishops’ Bible, and thus each was given a fresh, unbound copy (or part of a copy) to work from.[7] They also had before them the Hebrew Old Testament and the Greek New Testament, as well as all the earlier English translations. Their work, then, consisted more of editing than of translating. They worked through all parts of the text, beginning at their base in the Bishops’ Bible. They either kept its words or selected others they felt better represented the intent of the Hebrew and Greek originals. Sometimes they drew words directly out of earlier English translations. In general, their work succeeded best when they followed the original languages and the Geneva Bible (and hence Tyndale). It succeeded least when they remained true to their instructions to follow the Bishops’ Bible. Awkward words and passages from the Bishops’ Bible survived in many instances, but elsewhere, the translators wisely abandoned its readings and followed Geneva instead, often improving upon the Geneva Bible’s wording.

Thomas Matthew Bible, 1549, Genesis 1:28: "Growe and multiplye & fyl the erth."

Thomas Matthew Bible, 1549, Genesis 1:28: "Growe and multiplye & fyl the erth."

So how did we arrive at replenish in Genesis 1:28 and 9:1?

The Hebrew verb in question in those verses is mālē’, “fill.” In the Old Testament, various forms of it are used with respect to filling the earth with people (see Genesis 1:28), filling the tabernacle with the glory of God (see Exodus 40:34–35), jars being filled with water (see 1 Kings 18:33), and so forth. In seven places, King James’s translators used replenish for this verb, but in over two hundred other places, they used forms of the word fill. They even used fill for the same word in the parallel Creation account for ocean creatures, who were commanded to “Be fruitful, and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas” (Genesis 1:22).

In the fourth century AD, Jerome translated the Bible into Latin from Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. His translation, the Vulgate, became the standard Bible in Western Christianity for a thousand years. By William Tyndale’s time, Protestants had begun translating the Bible into modern languages. But in many cases, including in his, it was dangerous because for Roman Catholics, the Vulgate was the Bible, and any attempt to replace its authority with that of another translation was a crime. Tyndale paid for his English translations by being strangled and burned at the stake.

The basic Latin word for fill is pleo. At Genesis 1:28, Jerome used the verb repleo, “fill,” “refill,” “replenish.” In his translation of Genesis 9:1, from the identical Hebrew word, he used the verb impleo, “fill in.” That verb is close enough to the intended meaning, but a translation misses the mark if it takes repleo to mean that something had run out and needed to be resupplied. The Vulgate’s choice of words throughout the Bible had much influence on later translations, even those made by Protestants like the King James Version. This is likely a place where its impact is evident.

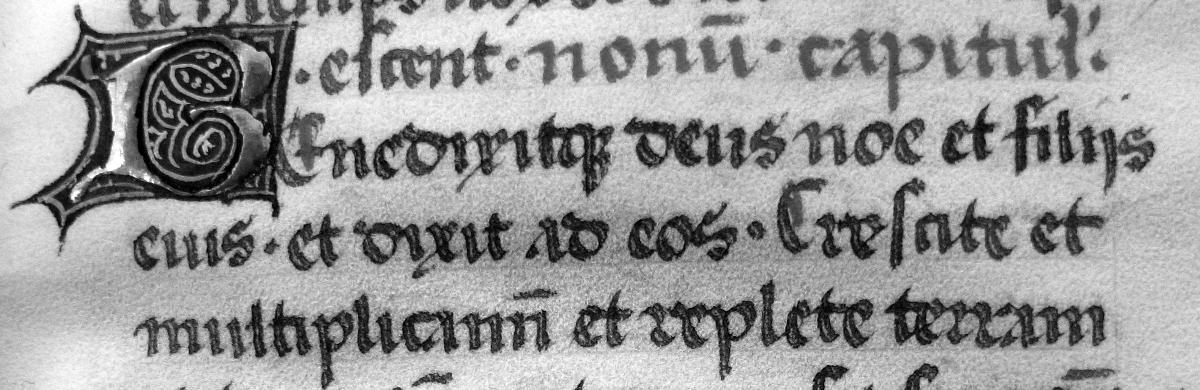

Latin Vulgate manuscript Bible, 1468, Genesis 9:1: "Crescite et multiplicami(ni) et replete terram," "Increase and multiply and replenish the earth."

Latin Vulgate manuscript Bible, 1468, Genesis 9:1: "Crescite et multiplicami(ni) et replete terram," "Increase and multiply and replenish the earth."

But it did not influence William Tyndale. When he translated the two passages from Hebrew, he used the standard English word fyll (spelling differences are inconsequential). The Coverdale and Matthew Bibles, which drew from Tyndale, used fyll as well, and the Geneva translators used fil.

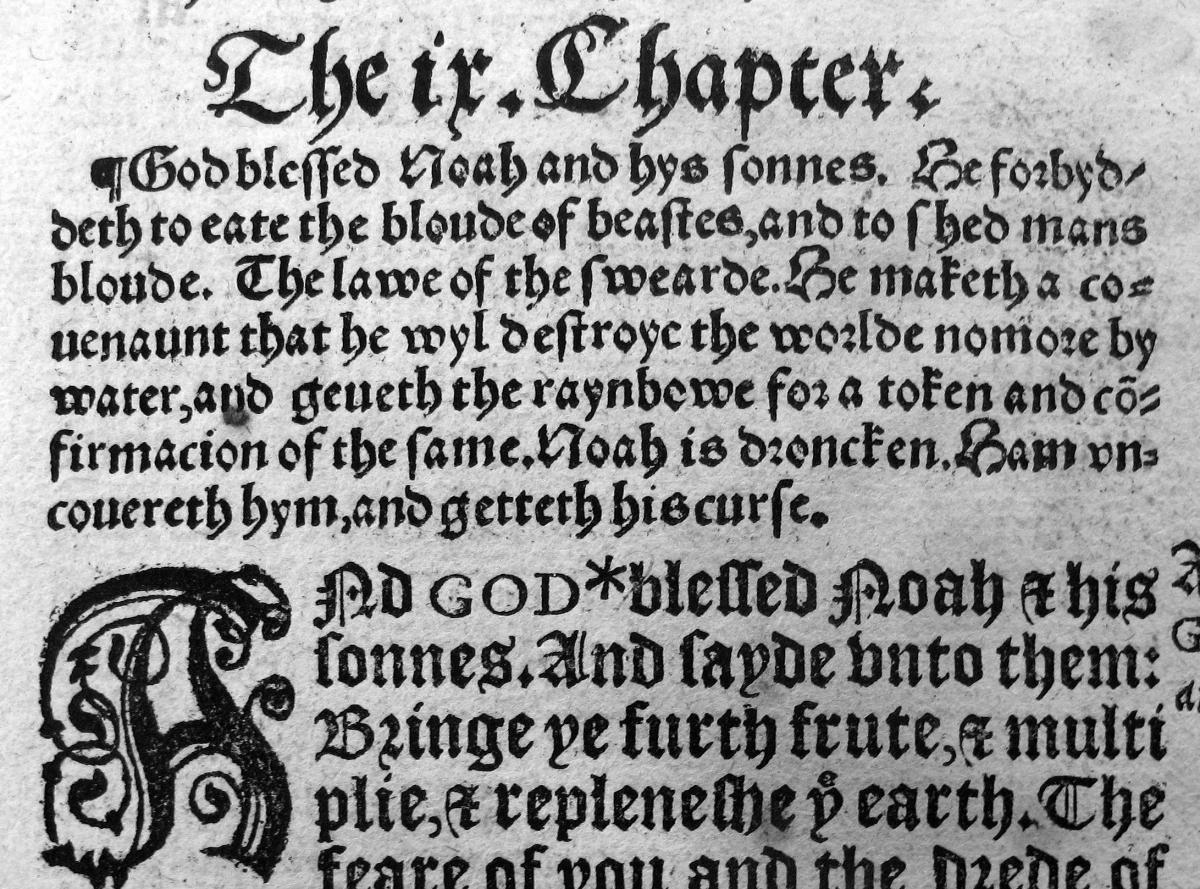

Great Bible, 1549, Genesis 9:1: "Bringe ye furth fruit, & multiple, & replenish the earth."

Great Bible, 1549, Genesis 9:1: "Bringe ye furth fruit, & multiple, & replenish the earth."

The creators of the Great Bible and the Bishops’ Bible gave us the word we have today, replenish. It is one of countless cases in which the Bishops’ Bible’s translators chose less-common Latin-based vocabulary over the plain English words that William Tyndale had used. Perhaps they used it because it sounded more sophisticated, more traditional, or more scripturally Latin. In any case, the word survived because the translators of the King James Bible kept it.

Bishops' Bible, 1591, Genesis 1:28: "Be fruitfull, and multiplie, and replenish the earth."

Bishops' Bible, 1591, Genesis 1:28: "Be fruitfull, and multiplie, and replenish the earth."

In the sixteenth century, the word plenish was in use in English, meaning “fill up,” “stock,” “furnish.”[8] The word replenish was also in use. Because it contains the prefix re-, which in English usually connotes doing something again, its root meaning is “refill.” But by the sixteenth century, replenish had taken on a history of its own, and in most instances it had become more or less synonymous with plenish.[9] Perhaps we can fault the King James translators for giving us a more obscure and less helpful word than fill, but we cannot fault them for the word’s meaning. It was a synonym of fill. Our problem today is that in modern usage, the root meaning of the re- in the word has returned, and now replenish no longer means “fill.”

The current wording is a doctrinal problem because it means something other than what is intended in the text. At least one early Latter-day Saint leader used replenish and its Latin components to argue in general conference that humans inhabited the earth before Adam’s time.[10] But the suggestion that Adam and Eve were “refilling” the earth is clearly not what the author had in mind. Thus, when the English Latter-day Saint edition of the Bible was published in 1979, it included footnotes at both Genesis 1:28 and 9:1 stating, “heb fill”—that is, the underlying Hebrew word actually means “fill.”[11]

Notes

[1] Title page, 1611 King James Bible, printed by Robert Barker (London); spelling standardized.

[2] An easy overview of the history of the English Bible to 1611 is Kent P. Jackson, “The English Bible: A Very Short History,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2011), 11–23. For William Tyndale, see David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994).

[3] Adam Nicolson, God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 193.

[4] John Nielson and Royal Skousen, “How Much of the King James Bible Is William Tyndale’s?,” Reformation 3 (1998): 49–74.

[5] David Daniell, ed., Tyndale’s New Testament: Translated from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1989), vii–xxxii; David Daniell, ed., Tyndale’s Old Testament: Being the Pentateuch of 1530, Joshua to 2 Chronicles of 1537, and Jonah (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), ix–xxxix.

[6] For the origin of the King James Bible in brief, see Lincoln H. Blumell and David M. Whitchurch, “The Coming Forth of the King James Bible,” in The King James Bible and the Restoration, 43–60. More extensive recent treatments are Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version, 1611–2011 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); and David Norton, The King James Bible: A Short History from Tyndale to Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

[7] David Norton, A Textual History of the King James Bible (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 35–36.

[8] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “plenish,” http://

[9] Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “replenish,” http://

[10] “The meaning of the word replenish is, to refill, recomplete. If I were to go into a merchant’s store, and find he had got a new stock of goods, I should say—‘You have replenished your stock, that is, filled up your establishment, for it looks as it did before.’ ‘Now go forth,’ says the Lord, ‘and replenish the earth.’ . . . The world was peopled before the days of Adam, as much so as it was before the days of Noah. . . . When God said, Go forth and replenish the earth; it was to replenish the inhabitants of the human species.” Orson Hyde, “The Marriage Relations,” Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1855–86), 2:79.

[11] Joseph Fielding Smith dealt with a question regarding the word replenish in an Improvement Era article, subsequently included in Joseph Fielding Smith, Answers to Gospel Questions, 5 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957–66), 1:208–11.