Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde’s 1837 Vision of the Infernal World

Christopher James Blythe

Christopher James Blythe, “Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde's 1837 Vision of the Infernal World,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 175–87.

Christopher James Blythe was a predoctoral teaching fellow in the History Department at Utah State University when this article was written.

Heber C. Kimball's experience with evil spirits taught him and his companions about the adversary's power and invisible realm. (Painting by John W. Clawson.)

Heber C. Kimball's experience with evil spirits taught him and his companions about the adversary's power and invisible realm. (Painting by John W. Clawson.)

I consider it a great privilege to offer this essay in honor of Richard Cowan. While I have not been blessed to be his student or his colleague, I have been benefitted and influenced by his work. His volume The Church in the Twentieth Century remains an important reminder to so many of us who focus in the nineteenth century that Church history has so much left to be explored. Brother Cowan has demonstrated the compatibility of faithful scholarship and academic rigor in a manner that is truly commendable.

The 1837 mission to Great Britain was a milestone in Church history. It was the first mission outside of the North America, and its eventual fruits swelled the ranks of the Saints in Nauvoo. There was little training or experience among the seven missionaries. Four of them had only recently found the gospel through the preaching of Parley P. Pratt in upper Canada. These converts were eager to accompany Heber C. Kimball, who had been called to preside over the mission, Orson Hyde, and Willard Richards on their journey. Kimball and Hyde were both ordained to the apostleship in 1835. As we think about this mission and the later coming of the majority of the Apostles in 1840, we are right to remember the miraculous conversion of many Latter-day Saints, the shaping of young men who would become great leaders in this dispensation, but also the real adversity faced by this first set of missionaries. Among the most well-known of these stories is the spiritual assault on Isaac Russell, Heber C. Kimball, and Orson Hyde, which occurred only ten days after their arrival in Preston, England. At the sesquicentennial commemoration of the opening of the mission to Great Britain, President Hinckley expected the Saints to already be at least vaguely aware of the story. He referred to it simply as “that terrifying experience” at Wilfred Street in Preston.[1]

Most Latter-day Saints who are familiar with this experience will know the latest account published in Orson F. Whitney’s Life of Heber C. Kimball in 1888. According to that account, on June 30, 1837, Apostles Heber C. Kimball and Orson Hyde were awakened when Isaac Russell charged into their room shouting, “I want you should get up and pray for me that I may be delivered from the evil spirits that are tormenting me to such a degree that I feel I cannot live long, unless I obtain relief.” The two laid their hands on his head to give him a blessing, when Heber C. Kimball himself was “struck with great force by some invisible power; and fell senseless on the floor.” Hyde and Willard Richards then laid their hands on Heber’s head, and he was revived enough to kneel for a prayer and then moved to the bed. It was then that both Kimball and Hyde began to witness that “a vision was opened to our minds, and we could distinctly see the evil spirits, who foamed and gnashed their teeth at us.” The experience was timed by Willard Richards, who noted that they were in vision for ninety minutes. [2]

This is a powerful scene that has offered many missionaries the opportunity to think deeply about their callings. In such contemplative moments, they might feel a kinship to Kimball and Hyde coming to realize that they had gained the devil’s attention and that evil opposition was very real indeed. More important, they might take courage to know that Whitney’s account includes Kimball’s returning home to meet with Joseph Smith to ask his opinion of the experience. Instead of finding concern, he learned that the Prophet had rejoiced that such an event had taken place: “I then knew that the work of God had taken root in that land.” Joseph assured Kimball that “the nearer a person approaches the Lord, a great power will be manifested by the adversary to prevent the accomplishments of His purposes.”[3]

Whitney’s account was published two decades after Kimball died and one decade after Hyde died. However, there were four earlier publications documenting the story, as well as several allusions to the experience in sermons, and even contemporary accounts recorded in journals and correspondence. This article will introduce readers to these various accounts of the spiritual assault in Preston and account for the varied manner in which the story has been told over time by looking at the effects of memory on the telling, including the conflation of multiple events into a single event.

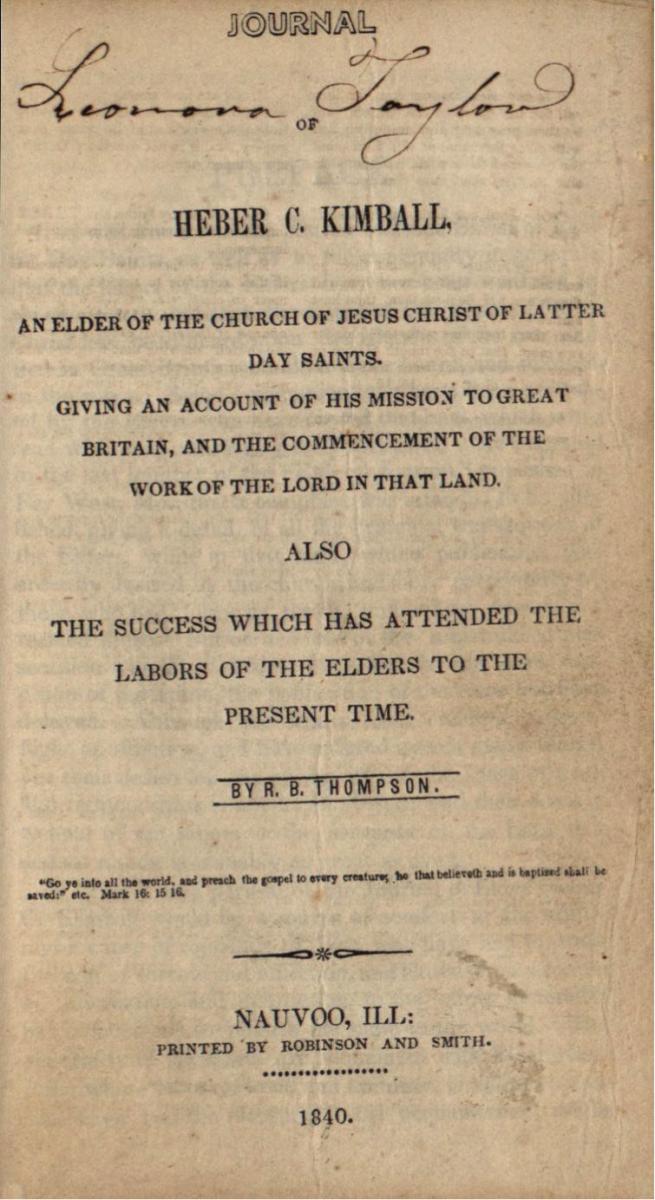

The Journal of Heber C. Kimball (1840) was the first published complete story of the missionaries' experience recounted for the Saints. (Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

The Journal of Heber C. Kimball (1840) was the first published complete story of the missionaries' experience recounted for the Saints. (Courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

The Earliest Published Accounts

The story of the missionaries’ “terrifying experience” first came to the attention of the Saints in Far West when The Elders’ Journal published a letter Kimball had written to his wife, Vilate, two months after the experience. He drew on the personal journal of Orson Hyde to document the event, although he confirmed its truthfulness:

A singular circumstance occurred before morning, which I will quote from Br. Hydes journal, as he wrote it down, he commences as follows, “Elder Russel was much troubled with evil spirits and came into the room where Elder Kimball and myself were sleeping, and desired us to lay our hands on him, and rebuke the evil spirit: I arose upon the bed, and Br. Kimball got upon the floor and I sat upon the bed; we laid our hands on him, and brother Kimball rebuked and prayed for him but just before he had finished his prayer, his voice faltered, and his mouth was shut, and he began to tremble and real [sic] to and fro, and fell on the floor like a dead man, and uttered a deep groan, I immediately seized him by the shoulder, and lifted him up, being satisfied that the devils were exceeding angry because we attempted to cast them out of Br. Russel, and they made a powerful attempt upon Elder Kimball as if to dispatch him at once, they struck him senseless and he fell to the floor; Br. Russel and myself then laid our hands on Elder Kimball, and rebuked the evil spirits, in the name of Jesus Christ; and immediately he recovered his strength in part, so as to get up; the sweat began to roll from him most powerfully, and he was almost as wet as if he had been taken out of the water, we could very sensibly hear the evil spirits rage and foam out their shame. Br. Kimball was quite weak for a day or two after: it seems that the devils are determined to destroy us, and prevent the truth from being declared in England.” The devil was mad because I was a going to baptize, and he wanted to destroy me, that I should not do those things the Lord sent me to do. We had a great struggle to deliver ourselves from his hands; when they left Br. Russel they pitched upon me, and when they left me they fell upon Br. Hyde; for we could hear them gnash their teeth upon us.[4]

The account shares much in common with the Orson F. Whitney variant except in two instances. First and most importantly, the event is exclusively heard, rather than seen. The missionaries’ attackers, though real, remain invisible. Second, in Kimball’s account it is Isaac Russell—the first missionary to be assaulted by the evil spirits—who assists Hyde in blessing Kimball, whereas in the Whitney account it is Willard Richards who assists Hyde. This discrepancy was introduced with the publication of The Life of Heber C. Kimball and may have been a mere transcription error. That Richards was not involved in blessing Kimball seems to be verified in his own journal account. He notes that he awoke to discover his “bedfellow Brother Russel Missing,” after which he “immediately repair[e]d to Bro. K[imball’s]. rooms & found him in bed.”[5] The action had already subsided.

The introduction of a visual aspect to Hyde and Kimball’s experience appeared three years later with the 1840 publication of The Journal of Heber C. Kimball. This volume was published as the Apostles—including Heber C. Kimball, who had returned to the United States in 1838—set off to preside over the mission in Great Britain. The Journal of Heber C. Kimball was an extremely important volume in the early Church, although the use of the term “journal” was actually a misnomer. Instead, we should consider this work a ghostwritten memoir, based in part on Kimball’s letters, but more importantly on the Apostle’s own memory of events that he shared with Robert B. Thompson. He later wrote in his journal that the conversation with Thompson occurred on a “high hill in the woods, near the city of Quincy, Illinois, where we sat down when I gave him a short sketch of my first mission to England.” The discussion was based solely “from memory, not having my journal with me.”[6] The resulting published account of the event reads:

About day break, Brother Russel (who was appointed to preach in the Market place that day,) who slept in the second story of the house in which we were entertained; came up to the room where Elder Hyde and myself were sleeping; and called upon us to rise and pray for him, for he was so afflicted with evil spirits that he could not live long unless he should obtain relief. We immediately arose, and laid hands upon him, and prayed that the Lord would have mercy on his servant and rebuke the devil, while thus engaged I was struck with great force by some invisible power and fell senseless on the floor, as if I had been shot; and the first thing that I recollected was, that I was supported by Brothers Hyde and Russel, who were beseeching a throne of grace on my behalf. They then laid me on the bed, but my agony was so great that I could not endure, and I was obliged to get out, and fell on my knees and began to pray, I then sat on the bed and could distinctly see the evil spirits who foamed and gnashed their teeth upon us. We gazed upon them about an hour and a half, and I shall never forget the horror and malignity depicted on the countenances of these foul spirits, and any attempt to paint the scene which then presented itself; or portray the malice and enmity depicted in their countenances would be vain. I perspired exceedingly, and my clothes were as wet as if I had been taken out of the river. Although I felt exquisite pain, and was in the greatest distress for some time, and cannot even now look back on the scene without feelings of horror; yet, by it I learned the power of the adversary, his enmity against the servants of God, and got some understanding of the invisible world. However the Lord delivered us from the wrath of our spiritual enemies and blessed us exceedingly that day, and I had the pleasure (notwithstanding my weakness of body, from the shock I had experienced, spiritual) of baptizing nine individuals and hailing them brethren in the kingdom of God.[7]

The vision has been inserted into the text as an obvious expansion of the 1837 account. When confronted by such a significant addition between Kimball and Hyde’s initial telling of their experience in Preston and this later narration, our tendency is to privilege the contemporary account and discount the amendment, perhaps based on Thompson’s misunderstanding of Kimball’s “short sketch.” Yet, Kimball would refer to the importance of this visual experience in several sermons. For example, on June 29, 1856, Kimball referred to this event with an expectation that his audience were already familiar with the Journal of Heber C. Kimball account and stated:

When I recovered I sat upon the bed thinking and reflecting upon what had past, and all at once my vision was opened, and the walls of the building were no obstruction to my seeing, for I saw nothing but the visions that presented themselves. Why did not the walls obstruct my view? Because my spirit could look through the walls of that house, for I looked with that spirit, element, and power, with which angels look; and as God sees all things, so were invisible things brought before me, as the Lord would bring things before Joseph in the Urim and Thummim. It was upon that principle that the Lord showed things to the Prophet Joseph.[8]

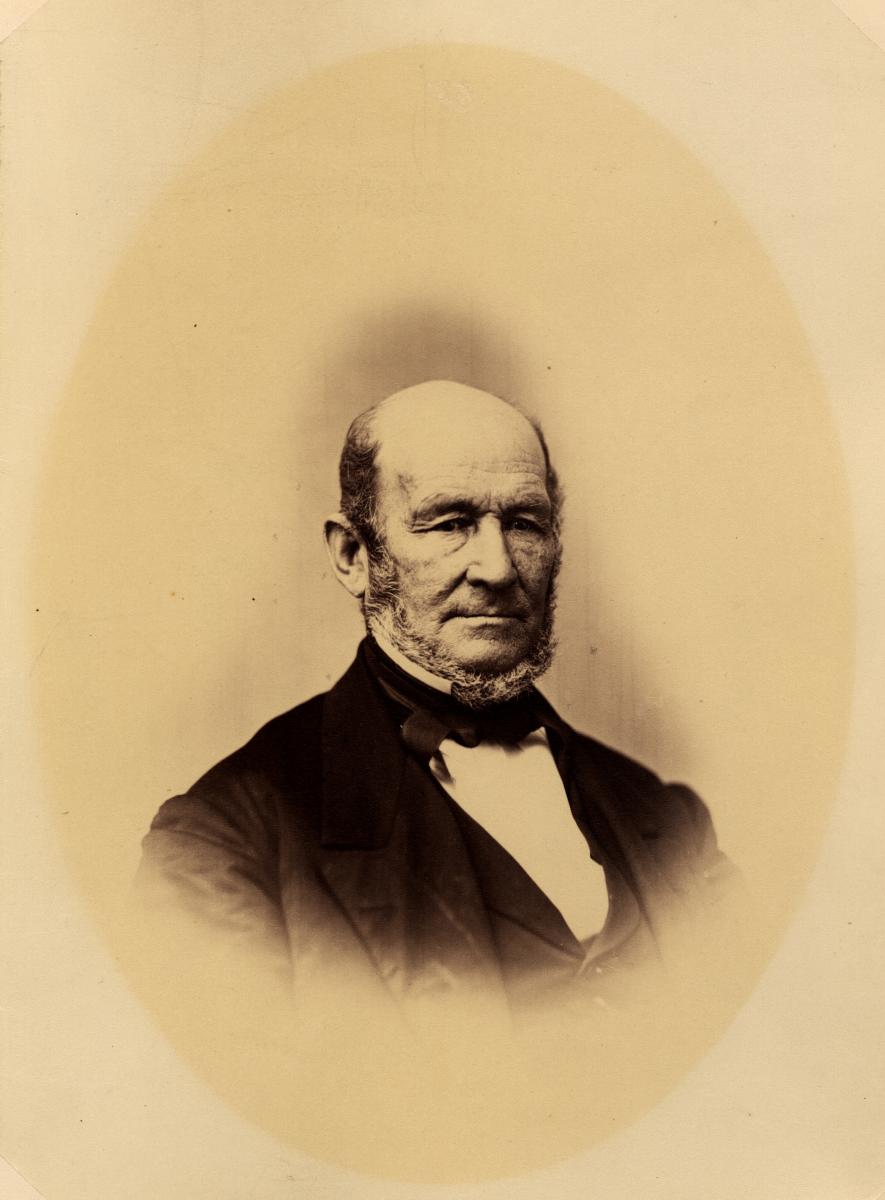

Brother Kimball's firsthand experience with the devils is a testament today to Saints of the power of the adversary. (Photo by Frederick H. Piercy, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Brother Kimball's firsthand experience with the devils is a testament today to Saints of the power of the adversary. (Photo by Frederick H. Piercy, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Orson Hyde would later claim that he too remembered the vision: “Every circumstance that occurred at that scene of devils is just as fresh in my recollection at this moment as it was at the moment of its occurrence, and will ever remain so. After you were overcome by them and had fallen, their awful rush upon me with knives, threats, imprecations and hellish grins, amply convinced me that they were no friends of mine.”[9]

Thus both Kimball and Hyde would later testify of this visual aspect of their experience. Fortunately, a contemporary source allows us to recognize that both the 1837 and 1840 accounts relate contemporary events. In the summer of 1837, Joseph Fielding, another of the English missionaries who was not then residing on Wilfred Street, recorded hearing Orson Hyde recount the details of the spiritual assault. What is so important about Fielding’s account is that he included both an experience in which Hyde and Kimball heard evil spirits and an experience in which they professed to have seen them occurring on two successive days. First, Fielding specified what events had occurred on the first day:

Early on Sunday morning, by Day light, having been much troubled through the night, he rose and went up to Elders Kimble and Hyde, to get them to pray with him. Bro H[yde] got up and they both laid their Hands on him and began to rebuke the Spirits. Bro. Kimble at least not fully believing Brother R[ussell]’s Testimony respecting his Case, and while he was praying his Speech began to falter, and he was thrown down on the Floor, and was in great Agony, so that the Sweat ran down his Face. All in an instant, he said it appeared as if every Part of his body was distorted, etc., to the utmost. It would have deprived him, he thought, of life in a few Minutes, but Bros. H[yde] and R[ussell] lifted him on the Bed, laid their hands on him and rebuked them, but he did not fully recover from its Effects for a Day or two. Bro H[yde] also received a severe gripe on one Thye [thigh]. They could hear a Sound from them, i.e. the Evil Spirits, like the grating of Teeth, quite plainly. All this appeared to be to prevent Bro. R[ussell] from preaching according to Appointment that Day in the Market Place. This design however was frustrated. Bro. R[ussell] preached and Bro. Goodson bore Testimony after him; I myself also spoke to a few People in a private house, and Bro. Kimball baptized 9 in the Morning.[10]

So far, Fielding’s account matches perfectly with Hyde and Kimball’s 1837 text. It occurred on Sunday morning before daylight. There was a physical assault by unseen but audible attackers. Kimball was tossed on the floor and required a blessing from Russell and Hyde, although he would suffer “from its effects” for the next “day or two.” Continuing, Fielding relates what Hyde told him occurred on the following night:

But on Sunday night Brother Russel was again greatly troubled in the same manner, and got Bro. Richards who slept with him, to go up to Bro. K[imball] and Bro. H[yde] and request them to come down to his relief. Here I am not certain whether it was before or after, but about this time, as Bro. Hyde declared, as he and Bro. Kimball were lying in Bed, himself being awake he saw as it were a host of those foul Spirits not on the Floor, but as it were in the Midst of the Room, in various Shapes and Forms; some [like] naked Women, misshapen, and ugly, some like Cats with half a head, etc., and others half of one Creature and half another, the most miserable and disgusting appearances one could possibly imagine. The[y] however kept their Distance, but turned their heads toward Bro. Hyde; one looking at him said distinctly, but with a murmuring tone, slowly demure, I never spoke against you. He said there seemed to be a legion of them. He was alarmed, but very much disgusted. He could scarcely bear to speak to them.[11]

On this second night, Kimball and Hyde were called down to assist Isaac Russell, who was once again afflicted with evil spirits. While it appears that Fielding was unsure whether the vision itself had occurred at this time or earlier in the evening, the details of the vision match all of the other accounts, including the least occurring element, in which Hyde converses with the spirits.

Scholars of memory have pointed to the ease by which memories may become distorted over time. In this case, the discrepancy between the 1837 and 1840 accounts of the spiritual assault can best be explained by the simple conflation of two related events occurring in a less-than-twenty-four-hour period. To be sure, this does not vindicate the way that the story has been told after 1840. In fact, it demonstrates that there is a flaw in these recollections; however, it supports the essential details of the experience as related across time.

A final detail of the experience, Kimball’s conversation with Joseph Smith over the nature of the vision, was elaborated in an 1882 account published in President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal, which like the 1840 Journal of Heber C. Kimball was a ghostwritten memoir—in the former case, a posthumous one. That being said, the new publication was written largely by Heber’s daughter, Helen Mar Whitney. In this account, Kimball went to Joseph Smith at the latter’s request after hearing Kimball had cast an evil spirit out of his home in Illinois. When he went to Joseph and told him these stories, he asked Joseph “what all these things meant, and whether or not there was anything wrong in me.”[12] This account suggests that Kimball was uncomfortable with his experience in Preston. While Kimball’s motivation in visiting Joseph Smith is not entirely clear from his own accounts, it is perhaps beneficial to consider his daughter’s perspective.

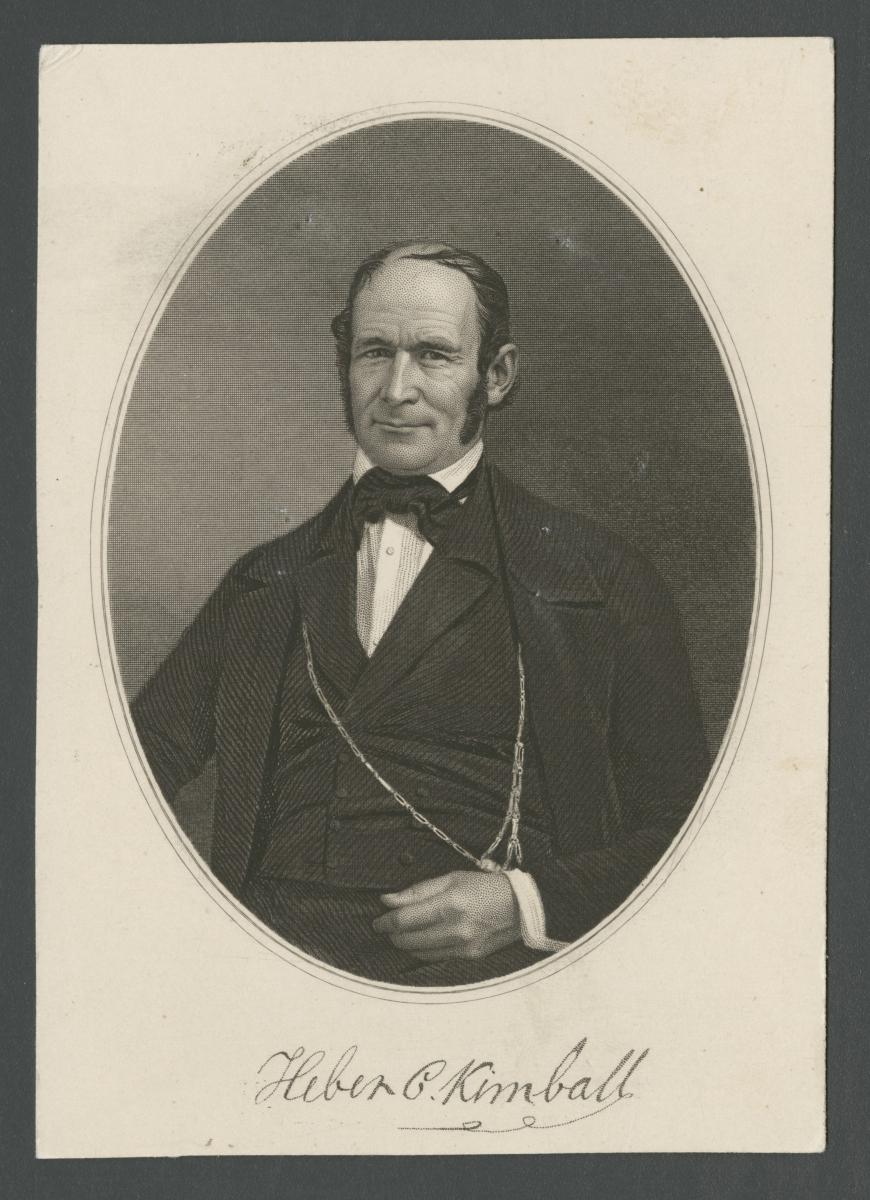

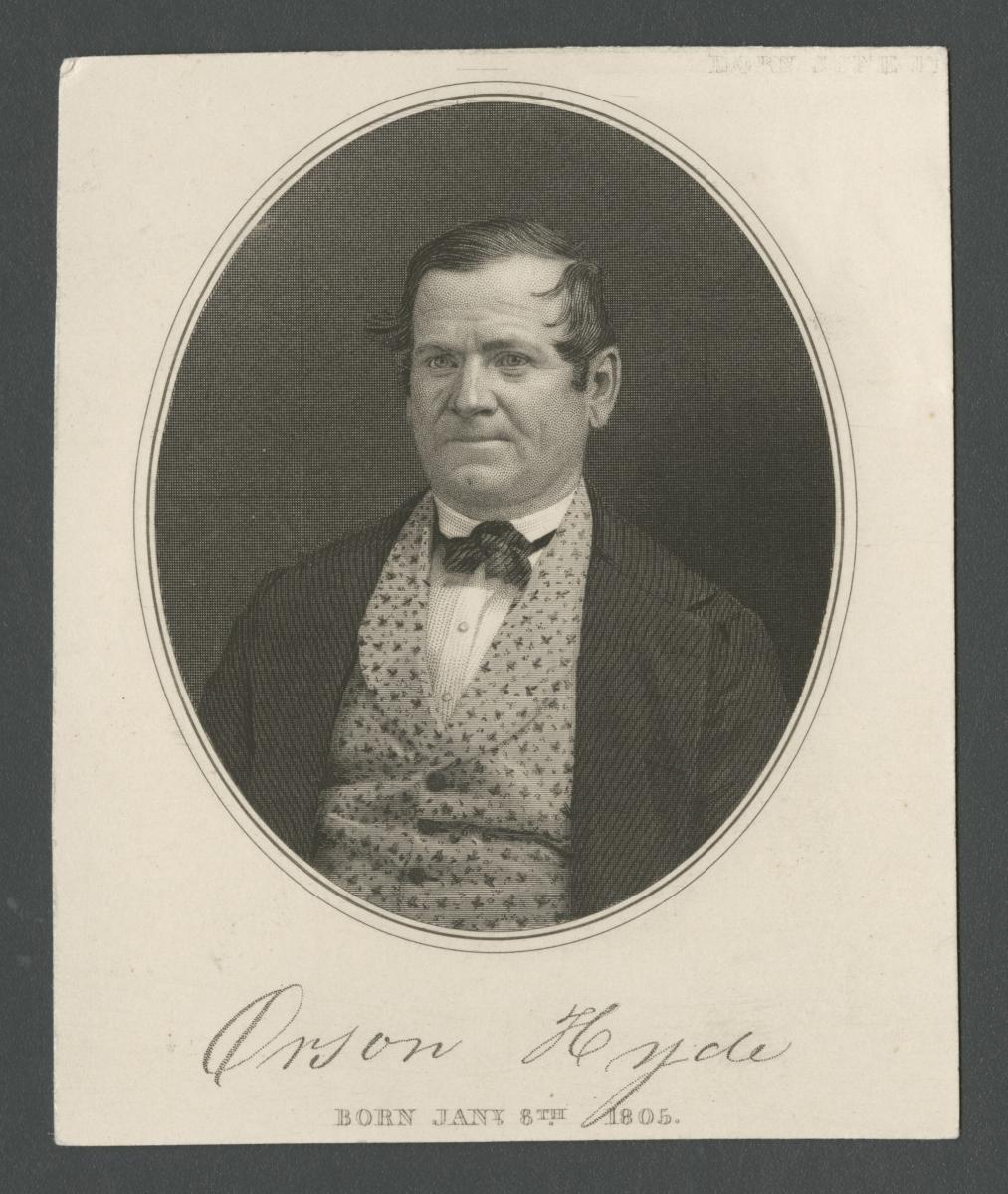

Together with Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde experienced this vision of the infernal world. (Photo by Frederick H. Piercy, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Together with Heber C. Kimball, Orson Hyde experienced this vision of the infernal world. (Photo by Frederick H. Piercy, courtesy of Church History Library.)

Heber C. Kimball was skeptical of Isaac Russell when the new convert professed to face evil spirits on that Saturday night. Although a secondhand account, Isaac Russell’s son offers an interesting take on the situation as he may have heard it from his father. He claimed that his father “could not sleep,” when

fiends from the infernal pit, as it were, gathered around him, tormenting him and grew worse as the night advanced. Alone he struggled with them until he could hold out no longer. He then arose and sought the bed where Brothers Kimball and Hyde were sleeping, calling upon them for relief through prayer in his behalf. Brother Heber C. Kimball may safely be termed at the time “one of those incredulous men” free from superstition or belief whatsoever in the hidden foe now about to assert their power for the destruction and overthrow of him and his brethren and the Gospel which they were seeking to establish in that land. Hence, as this was his first introduction and not wishing to be disturbed in his slumbers, he received Brother Russell rather gruffly, telling him it was all a notion of his and for him to “go back to bed.” Brother Russell replied, “If you don’t give me relief, I will die.”[13]

This seems to fit with the exasperated cry that Kimball refers to in his own account. Kimball’s initial skepticism is also borne out in Joseph Fielding’s account in which he noted that the Apostle was initially “at least not fully believing.”[14]

Thus, Helen Mar Kimball’s contention that her father went to Joseph with concern over the experience seems fair. Whether this was the reason he initially hesitated to relay the visionary nature of the next day’s experience is speculation, but would make sense given that it was a more dramatic encounter. Kimball had himself discussed Joseph’s reaction to the encounter. On March 2, 1856, he mentioned that Joseph had asked his wife for a copy of Heber’s letter in which he explained the event. According to Kimball, Joseph had told her, “It was a choice jewel, and a testimony that the Gospel was planted in a strange land.” When Kimball arrived in Nauvoo, he “called upon brother Joseph, and we walked down the bank of the river. He there told me what contests he had had with the devil; he told me that he had contests with the devil, face to face. He also told me how he was handled and afflicted by the devil, and said, he had known circumstances where Elder Rigdon was pulled out of bed three times in one night.” [15] Importantly, this is the only firsthand account of this experience, which did not include the spiritual lesson that would be contained in later accounts, but merely affirmed that such experiences were real.

Yet, as Helen Mar Whitney understood the experience, perhaps from hearing it firsthand from her father, she added details to Joseph’s counsel to Heber. “No, Brother Heber; at that time when you were in England, you were nigh unto the Lord; there was only a veil between you and Him, but you could not see Him. When I heard of it, it gave me great joy; for I then knew that the work of God had taken root in that land. It was this that caused the devil to make a struggle to kill you.” Joseph then said the nearer a person approached to the Lord, the greater power would be manifest by the devil to prevent the accomplishment of the purposes of God.”[16] Orson F. Whitney’s Life of Heber C. Kimball polished Helen Mar Whitney’s writing and now quotes Joseph in the above manner, but included within those quotations: “The nearer a person approaches the Lord, a greater power will be manifested by the adversary to prevent the accomplishments of His purposes.”[17]

Conclusion

The experience of Orson Hyde, Heber C. Kimball, and Isaac Russell with evil spirits while residing on Wilfred Street in Preston, England, remains a powerful moment in Latter-day Saint history. It was through this spiritual assault and its corresponding vision that Kimball “learned the power of the adversary, his enmity against the servants of God, and got some understanding of the invisible world.”[18] It was also at this time that the Apostles developed a greater appreciation for those who suffer adversity and for the power of God in delivering and protecting the Saints. While recounting personal experiences over the course of decades may lead to differences and imperfections in preserving the event exactly as it occurred, a careful examination of Kimball’s record and the records of those who witnessed the event demonstrate the essential details of the assault and corresponding vision.

Notes

[1] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Taking the Gospel to Britain: A Declaration of Vision, Faith, Courage, and Truth,” Ensign, July 1987, 6.

[2] Orson F. Whitney, The Life of Heber C. Kimball: An Apostle; the Father and Founder of the British Mission (Salt Lake City: Kimball Family, 1888), 143–44.

[3] Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, 145–46.

[4] Heber C. Kimball to Vilate Kimball, September 2, 1837, Elders’ Journal 1, no. 1 (October 1837): 4–5.

[5] Willard Richards Diary, 1837–1843, Leonard Arrington Papers, series IX, box 15, folder 1, Utah State University Special Collections, 7.

[6] Heber C. Kimball, autobiography, ca. 1842–58, MS 627, box 1, reel 1, Heber Chase Kimball Papers, 1837–66, Church History Library.

[7] R. B. Thompson, Journal of Heber C. Kimball: An Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Nauvoo, IL: Robinson and Smith, 1840), 19; emphasis added. The Heber C. Kimball Family Collection at the Church History Library includes a copy of the published Journal of Heber C. Kimball with edits made by Kimball (MS 23826). While he crossed out some passages written by Robert B. Thompson, he left this section intact with the exception of grammatical corrections.

[8] Heber C. Kimball, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1857), 4:2. When it comes to the details of the reports of Kimball’s sermons taken from the Journal of Discourses, readers should remember that there are certainly imperfections in this source. An entry on the lds.org Gospel Topics page warns that “questions have been raised about the accuracy of some transcriptions [within the Journal of Discourses]. Modern technology and processes were not available for verifying the accuracy of transcriptions and some significant mistakes have been documented.” https://

[9] Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, 145. I have been unable to locate the origin of this source.

[10] Journal of Joseph Fielding, MS 1567, 22–23, Church History Library.

[11] Journal of Joseph Fielding, 23.

[12] President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1882), 80.

[13] Samuel Russell, “Isaac Russell,” 42, Isaac Russell Family Collection, Vault MSS 497, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[14] Journal of Joseph Fielding, 22.

[15] Heber C. Kimball, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot,

1856), 3:229–30.

[16] President Heber C. Kimball’s Journal, 80.

[17] Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, 146.

[18] Thompson, Journal of Heber C. Kimball, 14.