Deconstructing the Sacred Narrative of the Restoration

Nicholas J. Frederick

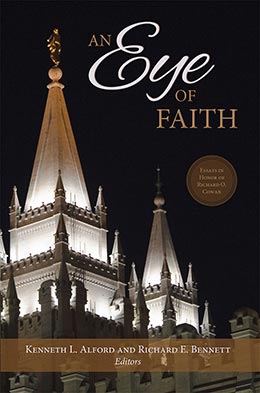

Nicholas J. Frederick, “Deconstructing the Sacred Narrative of the Restoration,” in An Eye of Faith: Essays in Honor of Richard O. Cowan, ed. Kenneth L. Alford and Richard E. Bennett (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, 2015), 235–55.

Nicholas J. Frederick was an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was written.

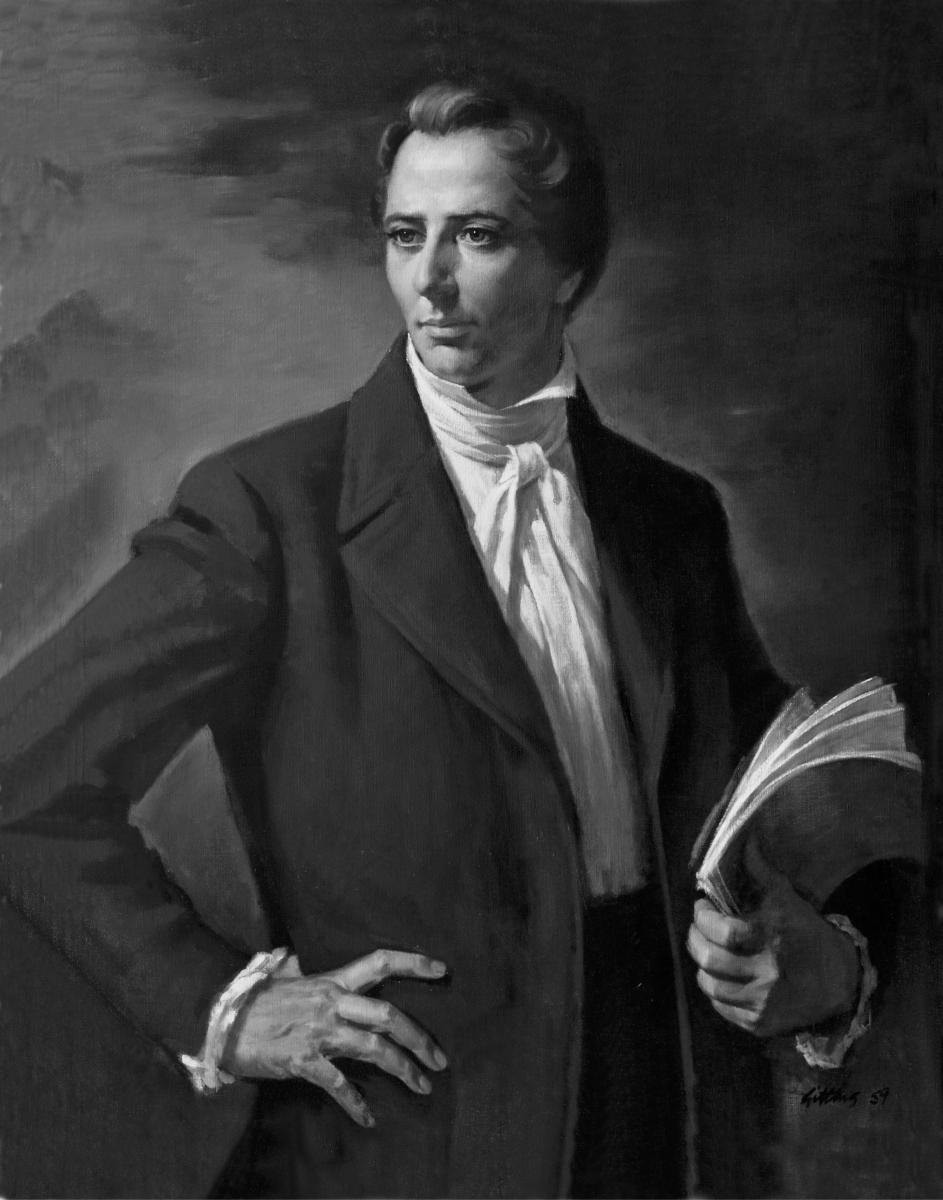

The Prophet Joseph Smith Jr. restored the Lord's Church on the earth in the latter days. (Painting by Alvin Gittins).

The Prophet Joseph Smith Jr. restored the Lord's Church on the earth in the latter days. (Painting by Alvin Gittins).

I have long been an admirer of Brother Richard Cowan. Even as an undergraduate at BYU, I enjoyed his numerous works bringing to life the LDS Church in the twentieth century (Temples to Dot the Earth remains a personal favorite). Since coming to BYU and teaching in Religious Education, I have had the pleasure of working right down the hall from Brother Cowan and have been continually amazed at the breadth of his knowledge and the depth of his love for students at BYU. I appreciate of his high spirits and good humor. He is an example to all those who study and love Latter-day Saint Church history, from the experts to the wannabes. (I include myself among the latter.)

In the conclusion to his insightful article exploring the development of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, James Allen asked, “Can we fully understand our heritage without understanding the gradual development of ideas, and the use of those ideas, in our history?”[1] The answer to Allen’s rhetorical question is a resounding no. As Latter-day Saints, we need to understand our history and theology as well as how they developed in order to understand our own heritage, our own story, our own narrative. Our sacred narrative is an intricate part of many believers’ experiences. In a recent evangelical publication aimed at helping non-Mormons understand their “Mormon neighbors,” Ross Anderson insightfully explained that “Mormonism is a faith defined not by theological formulations but by sacred narratives. . . . The two most important stories that define how Latter-day Saints understand their place in the universe are the story of the Restoration of true Christianity and the story of humanity’s potential for divine exaltation.”[2] Anderson’s statement is useful because it recognizes that, at its core, Mormonism often resists being defined by creed or tenets of faith in favor of sacred narratives that reflect the experiential nature of the faith, such as a premortal existence, Joseph Smith’s First Vision, the pioneer trek west, and even personal conversion accounts.

The purpose of this essay is to deconstruct one of Mormonism’s most important sacred narratives, specifically its narrative of the Restoration of the gospel, a narrative that includes fundamental events such as the Apostasy, the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, and the establishment of Zion. This narrative of the Restoration is important both because it was one of the earliest narratives to develop and because its evolution can be tracked with a fair amount of precision due to the sources available. This essay will examine the narrative of the Restoration by examining three specific sources: the revelations preserved in the Doctrine and Covenants, Joseph Smith’s 1833 N. C. Saxton letter, and Parley P. Pratt’s 1837 publication Voice of Warning. Using these three specific sources allows readers to observe the development of the Restoration through documents employing three different voices (the Lord, Joseph Smith, and Parley P. Pratt) as well as texts written in three different genres (revelatory, epistolary, and exhortatory). While disparate in voice and genre, all three sources share seven common elements that serve to establish the narrative of the Restoration.

While most Latter-day Saints are familiar with the revelations of Joseph Smith, his Saxton letter and Pratt’s Voice of Warning are likely less familiar and warrant brief introductions. On January 4, 1833, Joseph Smith dictated a letter to N. C. Saxton, the editor of the Evangelical paper American Revivalist, and Rochester Observer.[3] Carefully meshing his own language with biblical verse, Joseph Smith threw down the gauntlet to contemporary Christianity, claiming that Christianity was a “broken covenant” that lacked legitimate authority to lead believers to salvation. “Distruction [sic],” Joseph confidently proclaimed, was imminent. Joseph, however, had a solution that would mollify the wrath of the Lord, allowing men to “escape the Judgments of God which are almost ready to burst upon the nations of the earth.” Repentance and baptism performed by one “who is ordained and sealed unto this power” was requisite, Joseph stated. Additionally, he mentioned the coming forth of the Book of Mormon as well as the establishment of a latter-day Zion, both of which signified the beginning of the great eschatological event—the gathering of Israel. Joseph Smith ended the letter with a stern warning: “Repent ye Repent ye, and imbrace the everlasting Covenant and flee to Zion before the overflowing scourge overtake you, For there are those now living upon the earth whose eyes shall not be closed in death until they see all these things which I have spoken fulfilled.” Upon learning that Saxton had printed only an abbreviated form of his letter, he dictated a second, shorter letter on February 12, 1833, in which he chastised Saxton for not publishing his letter in full, warning him that “if you wish to clear your garments from the blood of your readers I exhort you to publish the letter entire but if not the sin be upon your head.” While Joseph’s request would go unheeded, the N. C. Saxton letter holds a significant place in Mormon history as the “earliest detailed declaration of the Church of Christ.”[4]

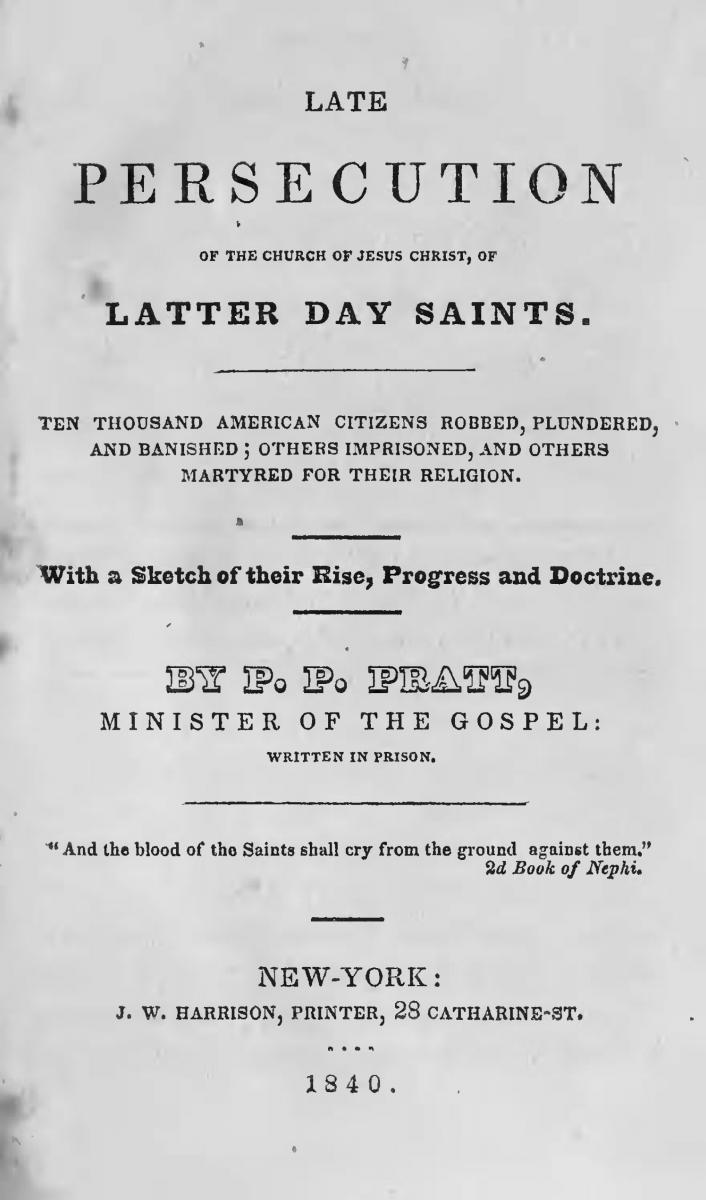

In 1837, Parley P. Pratt published his first pamphlet, Voice of Warning. Written quickly over a period of two months while Parley was staying in New York, Voice of Warning largely employed a common-sense approach to biblical verse, using the Bible to argue that a literal fulfillment of eschatological prophecy was at hand. Pratt’s work proceeded in a straightforward, logical manner. He began with chapters on prophecy fulfilled and yet to be fulfilled, followed by chapters on the construction of God’s kingdom, the significance of the Book of Mormon, and the true meaning of the “Restoration.” Echoing the voice of John the Baptist, Pratt warned his readers about the imminence of God’s true kingdom and boldly called upon the Christian world to repent: “O! my brethren according to the flesh, my soul mourns over you; and had I a voice like a trumpet, I would cry, awake, awake, and arouse from your long slumbers, for the time is fulfilled, your destruction is at the door. . . . Repent ye, repent ye, for the great day of the Lord is at hand.”[5] In the words of Pratt’s biographers, Voice of Warning “became the principal vehicle presenting Mormonism to the Latter-day Saint faithful and the general public alike, and it was elevated by both to near canonical status.”[6]

What emerges from a study of the revelations, the Saxton letter, and Voice of Warning is a sacred narrative of the Restoration constructed around seven key points, each of which we will closely examine: The world is currently in a state of apostasy resulting from a broken covenant. Because of this apostasy, the world must repent and align themselves with the new covenant God has formed with Joseph Smith, a covenant signified by the Book of Mormon. The coming forth of the Book of Mormon will set in motion the gathering of Israel to the yet-to-be-established city of Zion.

Cover page for A Voice of Warning and Instruction to All People, written by Parley P. Pratt. (Courtesy of the Rare Book Collection, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

Cover page for A Voice of Warning and Instruction to All People, written by Parley P. Pratt. (Courtesy of the Rare Book Collection, Harold B. Lee Library, BYU.)

Apostasy

In a revelation given during a special conference of the Church held at Hiram, Ohio, in November 1831, the Lord revealed his “preface” to the previously received revelations, canonized in 1835 as section 1 in the Doctrine and Covenants.[7] One of the pivotal messages strewn throughout this revelation was the Lord’s emphatic decree that the world currently lived in a state of darkness and rebellion because “they have strayed from mine ordinances & have broken mine everlasting Covenant.”[8] The Lord continued, speaking of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon before describing the establishment of the restored Church, an institution that would be brought forth “out of obscurity & out of darkness the only true & living Church upon the face of the whole Earth with which I the Lord am well pleased.”[9] This revelation contains some of the Lord’s most potent rhetoric, which served to underscore the fundamental nature of the Restoration and provided a worthy introduction from a revelatory corpus that functioned as “a ‘voice of warning’ to the world to prepare them for Jesus Christ’s second coming.”[10] As historian Steven C. Harper has observed, section 1 “outlines the Lord’s rationale for opening the last dispensation. The world was apostate, and the omniscient Lord has seen the devastating potential of such apostasy. He has provided a solution by calling a prophet, Joseph Smith, and giving him revelations.”[11]

After a brief introductory paragraph, Joseph Smith begins the Saxton letter with the observation, “For some length of time I have been car[e]fully viewing the state of things as now appear throug[h]out our christian Land and have looked at it with feelings of the most painful anxiety while upon the one hand beholding the manifested withdrawal of Gods holy Spirit and the vail of stupidity which seems to be drawn over the hearts of the people.” While Joseph Smith doesn’t explicitly use the word “apostasy” here (as he will further on in the letter), the reference to a “vail of stupidity” combined with the “manifest withdrawal of Gods holy Spirit” and the subsequent call for the world to “awake out of sleep” leaves little doubt as to his meaning.

In Voice of Warning, Parley P. Pratt concludes his lengthy scriptural argument for the fulfillment of biblical prophecy with a statement echoing Joseph Smith’s: “Alas, has it come to this; has the spirit of truth removed the veil of obscurity from the last days, only to present us with a vision of a fallen people; an apostate Church, full of all manner of abominations, and even despising those who are good; while they themselves, have nothing left but the form of godliness, denying the power of God, that is setting aside the direct inspiration, and supernatural gifts of the Spirit, which ever constitute the Church of Christ.”[12] The language of Joseph Smith and Parley P. Pratt serve as additional witnesses to the claim made by the Lord in the November 1831 revelation and further emphasize the apostate spirituality of contemporary Christianity.

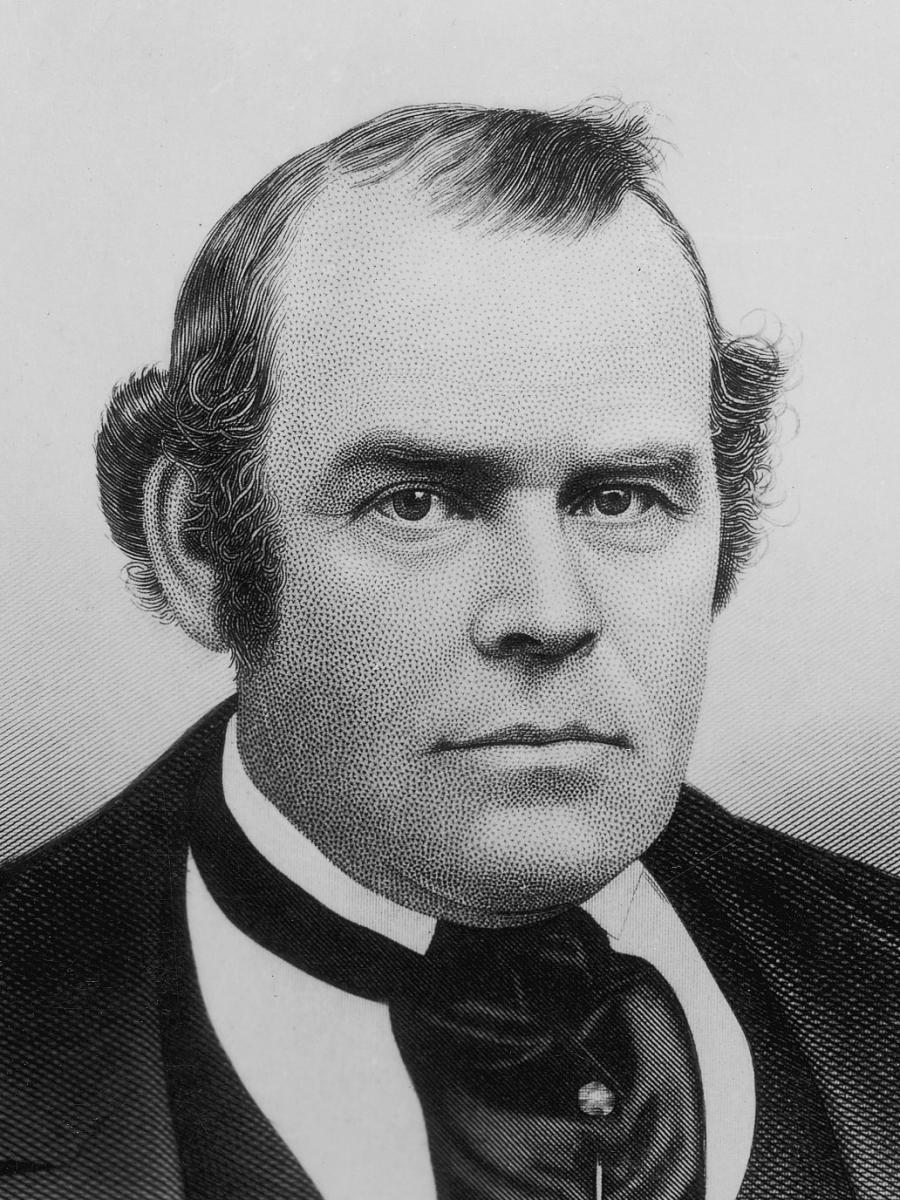

Parley Parker Pratt (1807-57) wrote A Voice of warning, along with numerous other religious pamphlets.

Parley Parker Pratt (1807-57) wrote A Voice of warning, along with numerous other religious pamphlets.

The Broken Covenant

Establishing that the Christian world was currently in a state of apostasy leads to the second point of the Restoration narrative, namely the broken covenant. Neglect of the covenants formed between God and humanity has directly led to the Apostasy. In a brief revelation given shortly after the organization of the Church in April 1830 and now canonized as section 22, Joseph Smith was instructed on how to handle potential converts who had already received the ordinance of baptism from a different church:

Behold I say unto you that all old covenants have I caused to be done away in this thing, and this is a new and everlasting covenant; wherefore, although a man should be baptized a hundred times it availeth him nothing, for ye cannot enter in at the straight gait by the law of Moses, neither by your dead works, for it is because of your dead works that I have caused this last covenant and this church to be built up unto me; wherefore enter ye in at the gate as I have commanded, and seek not to counsel your God.[13]

In this revelation, the Lord asserts that a “new” and “everlasting” covenant was necessitated due to the “dead works” of other denominations. The statement “all old covenants have I caused to be done away in this thing” indicates that certain covenants were formerly in place but no longer held any legitimacy, covenants that were, at least from the Lord’s perspective, “broken.”

In the Saxton letter, Joseph Smith takes what section 22 states implicitly and makes it explicit. Using the themes of the scattering of the Jews and the impending judgment now facing the Gentiles, the Saxton letter advances the claim that the Gentiles had “broken” their covenant with Jesus: “the Gentiles have not continued in the goodness of God but have departed from the faith that was once delivered to the saints and have broken the everlasting covenant in which their fathers were established.”

In a manner similar to that of Joseph Smith, Parley P. Pratt transitions from the discussion of the gathering to the claim that the Gentiles currently live under a broken covenant: “It therefore remains for us to prove that that covenant has been broken, completely broken, so that it is not in force, either among Jew or Gentiles, having lost its offices, authorities, powers, and blessings, insomuch that they are no where to be found among men.”[14] Pratt then begins a lengthy argument from scripture which, like the Saxton letter, draws upon Romans 11 and Isaiah 24 for scriptural support. Pratt’s conclusion is that the covenant indeed has been broken: “And the complaint is that the earth is defiled under the inhabitants thereof, because they have transgressed the laws, changed the ordinances, and broken the everlasting covenant.”[15] With statements that echo the baptism controversy that inspired section 22, both men claim as the clearest indications of the broken covenant the loss of New Testament church organization/

The Need for Repentance

With the Apostasy in full effect following the breaking of the covenant, the only way for humanity to regain their proper spiritual course was to repent. Several of the early revelations[17] of Joseph Smith are filled with the injunction to preach repentance to the world, particularly those revelations focused upon missionary work: “Say nothing but repentance unto this generation; keep my commandments and assist to bring forth my work according to my commandments, and you shall be blessed.” Altogether, the words “repent” and “repentance” occur fifty-four times in the revelations received by Joseph Smith beginning with section 3 (July 1828) and continuing up through section 45 (March 7, 1831).

In the opening of the Saxton letter, Joseph Smith begins his jeremiad with a call “for a christian world to awake out of sleep and cry mightely to that God day and night whose anger we have Justly incured.” The confidence Joseph Smith demonstrates in the opening of the letter is striking, employing “I” no fewer than six times, positioning himself as a latter-day Jeremiah urging the modern “Babylonians” to repent. Like Moses and Isaiah, he is cognizant of his own perceived inadequacy, writing that “I leave an inteligent community to answer this important question with a confession that this is what has caused me to overlook my own inability and expose my weakness to a learned world but trusting in that God who has said these things are hid from the wise and prudent and reve[a]led unto babes,” while continuing to emphasize that his message comes not from the minds of men but from the mouth of God himself: “I step forth into the field to tell you what the Lord is doing and what you must do to enjoy the smiles of your saviour in these last day[s].” This opening paragraph establishes two key points: Joseph Smith’s prophetic role and the necessity for repentance due to current corruption and sin.

In a manner that complements the prophetic claims of the Saxton letter, Pratt begins Voice of Warning with a lengthy discussion of prophecy, emphasizing the surety of its fulfillment. As the evidence for the claim that the Latter-day Saints possess an authoritative means of prophecy, Pratt alludes to 2 Peter 1:20: “For this we will not depend on any man or commentary, for the Holy Ghost has given it by the mouth of Peter: ‘Knowing this first, that no prophecy of the Scripture is of any private interpretation,’” and initiates a lengthy summary of biblical verse in which prophecy was fulfilled. The argument about the surety of prophecy’s fulfillment in chapter 1 serves to buttress the claims of chapter 2, namely that additional biblical prophecy stands ready for fulfillment. Chapter 2 closes with a lengthy call for observant Christians to repent, a key term reflecting the title of the work and a word Pratt will employ forty-eight times throughout Voice of Warning.[18]

Joseph Smith Jr. wrote the Saxton Letter, in which he "claims that entrance into the 'new covenant' can only be accomplished through the exercising of proper authority through 'the laying on of the hands of him who is ordained and sealed unto this power, that ye may receive the holy spirit of God." (Design Farm).

Joseph Smith Jr. wrote the Saxton Letter, in which he "claims that entrance into the 'new covenant' can only be accomplished through the exercising of proper authority through 'the laying on of the hands of him who is ordained and sealed unto this power, that ye may receive the holy spirit of God." (Design Farm).

The New Covenant

Following the assertion of a broken covenant and an injunction to repent, our three sources elaborate on the meaning and purpose of the “new covenant.” In revelations received prior to January 1833, the word “covenant” appears forty-four times. While some of these usages seem to be synonymous with “commandments” (such as D&C 42:13, 78), or a reference to individual covenants (such as D&C 54:4 and D&C 25:13), on three occasions “covenant” is combined with “new.”[19] In addition to the mention of a “new and everlasting covenant” discussed above, the phrase appears on two other occasions, D&C 76:69 and D&C 84:57. The use of “new covenant” in the former is likely modeled after similar language in Hebrews 11, but the use of “new covenant” in the latter gives some indication that Joseph Smith’s understanding of “new covenant” included the circumstances surrounding the coming forth of the Book of Mormon and the revelations contained in the Book of Commandments.[20]

Following discussion of the calamities of the present and future age, both the Saxton letter and Voice of Warning turn their attention toward escaping God’s impending judgment. Avoidance of this judgment, according to both, is to become part of God’s kingdom, what Joseph Smith refers to in the Saxton letter as the “new Covenant.”[21] Alluding to Acts 2, Joseph Smith claims that entrance into the “new covenant” can only be accomplished through the exercising of proper authority through “the laying on of the hands of him who is ordained and sealed unto this power, that ye may receive the holy spirit of God, and this according to the holy scriptures, and of the Book of Mormon; and the only way that man can enter into the Celestial kingdom. These are the requesitions of the new Covenant or first principles of the Gospel of Christ.”[22]

Pratt likewise focuses upon the nature of the “new covenant” and what one must do to enter into it. After a discussion of Acts 2, Pratt develops the idea that legitimate authority was requisite for the proper functioning of God’s kingdom, which authority Pratt argued was presently absent from the Christian world: “‘But the reader inquires with astonishment—what! is none of all the ministers of the present day called to the ministry, and legally commissioned? Well, my reader, I will tell you how you may ascertain from their own mouths, and that will be far better than for me to answer; go to the clergy and ask them if God has given them any direct Revelation, since the New Testament was finished, . . . and in short they will denounce every man as an impostor who pretends to any such thing.”[23] For Pratt, direct authority from God was crucial. Entrance into God’s kingdom could come by no other means: “Now reader, I have done our examination of the kingdom of God, as it existed in the apostles’ days; and we cannot look at it in any other age, for it never did, nor never will exist, without Apostles and Prophets, and all the other gifts of the Spirit.”[24]

The Book of Mormon

Having introduced the topic of the “new covenant,” our sources elaborate upon the significance that the coming forth of the Book of Mormon will have as the Lord builds up his latter-day kingdom upon the earth. Sometime after losing 116 manuscript pages that he and Martin Harris had translated from the large plates, Joseph Smith received a revelation that is now canonized as section 10. In this revelation, the Lord warned Joseph not to retranslate the lost portion, but to use the small plates to fill in the gap left by the loss of the 116 pages. Additionally, the Lord spoke concerning the role that the Book of Mormon would play in the Restoration. Speaking of the Book of Mormon authors, the Lord stated, “yea, and this was their faith, that my gospel which I gave unto them, that they might preach in their days, might come unto their brethren, the Lamanites, and also, all that had become Lamanites, because of their dissensions. Now this is not all, their faith in their prayers were, that this gospel should be made known also, if it were possible that other nations should possess this land.” Thus the coming forth of the Book of Mormon would serve to complement the information the Christian world already had obtained from the Bible: “And now, behold, according to their faith in their prayers, will I bring this part of my gospel to the knowledge of my people. Behold, I do not bring it to destroy that which they have received, but to build it up.”[25] The early importance of the Book of Mormon can be seen in how vigorously the book was used in early missionary efforts. Before the Book of Mormon had even been published, early missionary Solomon Chamberlain took proofs with him to Canada. Samuel Smith initially failed in his attempt to sell copies of the Book of Mormon in the summer of 1830, but his efforts eventually led to men like Brigham and Joseph Young reading the book and becoming baptized.[26]

Joseph Smith made only a brief mention of the Book of Mormon in the Saxton letter, but what he does say indicates that he viewed the Book of Mormon as playing a critical role in the Restoration process that would accompany the establishment of the “new covenant.” Joseph Smith declared, “The Book of Mormon is a record of the forefathers of our western Tribes of Indians, having been found through the ministration of an holy Angel translated into our own Language by the gift and power of God. . . . By it we learn that our western tribes of Indians are desendants from that Joseph that was sold into Egypt, and that the land of America is a promised land unto them, and unto it all the tribes of Israel will come. with as many of the gentiles as shall comply with the requesitions of the new co[v]enant.”

Pratt’s discussion of the Book of Mormon in Voice of Warning is much lengthier, quoting extensive sections of the Book of Mormon while being particularly focused upon providing geographic proof for ancient American residents. He devotes several pages to a discussion of the origins of the text, highlighting circumstances involved in the book’s appearance, and even includes events omitted by Smith, such as the visit with Charles Anthon and the Three and Eight Witnesses. But Pratt appears less concerned with what the Book of Mormon taught than what it meant.[27] Significantly, he viewed the discovery and translation of the Book of Mormon as the sign of Joseph Smith’s valid authority and thus the signifier of the Restoration—there could be no kingdom of God without the Book of Mormon. Crucially, the Book of Mormon, both by its content and its very existence, offered physical proof of the Restoration.[28]

The Gathering of Israel

The idea of the eschatological “gathering of Israel” that would be a major facet of the “new covenant” was a major emphasis in both the Book of Mormon and the revelations received in the months following the organization of the Church. In September 1830, Joseph received what is now section 29, wherein the Lord emphatically charged the leadership of the Church to set in motion the “gethering of mine Elect for mine Elect hear my voice & harden not their hearts wherefore the decree hath gone forth from the father that they shall be gethered in unto one place upon the face of this land to prepare their Hearts & be prepared in all things against the day of tribulation & desolation is sent forth upon the wicked.”[29] A month later, Joseph Smith relayed a revelation to Ezra Thayne and Northrop Sweet that echoed the words of the September revelation: “even so will I gether mine elect from the four quarters of the Earth even as many as will believe 〈on〉 my name & hearken unto my voice yea Verily Verily I say unto you that the field is white already to harvest Wherefore thrust in thy sickles & reap with all thy mights mind & strength.”[30] Subsequent revelations, such as the ones now canonized as sections 37, 38, 52, and 57 would continue to stress the issue of the gathering, especially as the Saints made the trek to Ohio in 1831.[31]

As laid out in the Saxton letter, Joseph Smith clearly believed that the gathering would be a defining moment in history as well as the fulfillment of biblical prophecy. In a passage filled with the covenant language of the Old Testament, Joseph declares, “The time has at last come arived when the God of Abraham of Isaac and of Jacob has set his hand again the seccond time to recover the remnants of his people which have been left from Assyria, and from Egypt and from Pathros &.c. and from the Islands of the seal and with them to bring in the fulness of the Gentiles and establish that covenant with them which was promised when their sins should be taken away.”

In Voice of Warning, Pratt likewise pays close attention to the pivotal nature of the gathering of Israel. As he begins his second chapter on the “Fulfillment of Prophecy Yet Future,” Pratt, like Joseph Smith, cites Isaiah 11:11–16 before explicitly describing the divine function of the latter-day gathering of Israel: “But the God of Heaven is to call men by actual Revelation, direct from Heaven, and to tell them who Israel is; who the Indians of America are, if they should be of Israel, and also where the ten tribes are, and all the scattered remnants of that long lost people.”[32] Readers may sense in portions of Voice of Warning such as this one Pratt’s attempt to make explicit what earlier writings, such as the Saxton letter, had stated implicitly. Where Joseph Smith quotes a line or two from Isaiah, Pratt quotes the full entire scriptural reference. Where Joseph mentions the forthcoming gathering of Israel, Parley will explain the practicality behind it, focusing upon the missionary agents of the gathering and the identity of those who are in need of gathering. With the focus now upon the gathering of Israel, the narrative of the Restoration moves temporally from an emphasis upon the present to highlighting the eschatological events of the future.

Zion

This eschatological future reaches a climax with the introduction and development of the concept of Zion. This idea of a physical gathering place, termed “Zion” or the “new Jerusalem,” was known to Joseph Smith as early as 1829. The Book of Mormon contains a promise that “a New Jerusalem should be built up upon this land, unto the remnant of the seed of Joseph, for which things there has been a type” (Ether 13:6). Early revelations received by Joseph Smith exhort Martin Harris (D&C 6) and Hyrum Smith (D&C 11) to “keep my commandments, and seek to bring forth and establish the cause of Zion” (D&C 6:6; cf. D&C 11:6). Prior to his mission to the Lamanites in October 1830, Oliver Cowdery wrote and signed a “Covenant” in which he stated that the Lord had charged him to “rear up a pillar as a witness where the Temple of God shall be built, in the glorious New-Jerusalem.”[33] This document is “the first recorded use of the term New Jerusalem following the establishment of the church.”[34] Subsequent revelations, in particular Doctrine and Covenants 28, 29, and 45, as well as the vision of Enoch (which was received at the same time Cowdery and his companions were preparing for their Lamanite mission), all contributed to fleshing out and further rooting the concept of Zion as a reality in the minds of the nascent Church.

In the final portion of the Saxton letter, Joseph Smith highlights the vital role Zion was to play in the eschatological fulfillment of the Restoration. Events were already under way, Joseph Smith proclaimed, that would culminate in God’s people gathering to the latter-day Zion or Jerusalem: “These are testamonies that the good Shepherd will put forth his own sheep and Lead them out from all nations where they have been scattered in a cloudy and dark day, to Zion and to Jerusalem beside many more testamonies which might be brought.” Part of this gathering process, Joseph Smith prophesied, would be an event that “has not a parallel in the hystory of our nation” but would prepare the “return of the lost tribes of Israel from the north country.” Perhaps most remarkably, he spoke of a gathering of the “new covenant” that was already under way “to Zion which is in the State of Missouri.” The year 1833 found Joseph deeply engaged in constructing his American Zion, and it is not surprising to see this topic serve as the climax of his letter.

Parley P. Pratt likewise turns his attention in his last chapter to the Restoration and the establishment of Zion in the last days. Following a lengthy discussion of the biblical prophecies of Ezekiel and Isaiah, Pratt concludes: “There is a city to be built in the last days, unto which not only Israel, but all the nations of the gentiles are to flow, and the nation and kingdom that will not serve that city shall perish, and be utterly wasted[.] Second, we learn that the name of that city is Zion, the city of the Lord, Third, we learn that it is called the place of his sanctuary, and the place of his feet.”[35] Again, Pratt is capable of providing a remarkable expansion of his topic, in this case carefully teasing out several elements fundamental to the nature and reality of Zion.[36]

For Pratt, the establishment of Zion was something that could be measured rationally. He provides a timeline for its construction and evolution, elaborating upon which people are going to occupy its borders and the nature of its relationship with its biblical twin. The fact that Zion had not been fully realized did not make it, at least for Pratt, any less real.

Hopefully, this examination of early Mormon documents brings to the surface the distinct elements of one sacred narrative that helps to confirm the foundation of the Mormon Church for believing members. Perhaps these seven points seem obvious to the modern reader as the foundation of the Mormon story, especially for those raised within the Church, because they are so clearly part of our modern conception of ourselves. However, it is valuable to note that the reason these are part of our modern conception is largely because these seven points were ingrained as part of the Mormon sacred narrative from the very beginning.

In his analysis of narratives, Richard Kearney observes that “the essential meaning of tradition—from the Latin tradere, [is] to transfer,” thus “carrying as it does the present into the past and the past into the present.”[37] This collision of past and present can certainly be seen in the early Mormon narrative of the Restoration, a sacred narrative where elements such as the scattering and gathering of Israel, old covenants and new covenants, old scripture and new scripture, and Enoch’s Zion and Joseph Smith’s New Jerusalem are carefully woven together in a way that concretizes the abstract elements of a sacred history. The result of this weaving is the formation of a historical tapestry, one that stretches back to the beginnings of God’s first dealings with humanity. As historian Richard Bushman has observed, “More than restoring the New Testament church, the early Mormons believed they were resuming the biblical narrative in their own time.”[38] Yet at the same time the narrative paved the way for a unique future. Joseph Smith and the Latter-day Saints were not simply another stage in biblical history—they were the final stage. While other dispensations may have come and gone, while other prophets may have restored God’s eternal truths, Joseph’s dispensation was the fulness of times. With the revelations and the Saxton letter, Joseph Smith successfully delineated his role and that of the Mormon Church as the visible force behind the “new covenant,” one that would successfully gather Israel to Zion, setting the stage for Jesus Christ’s triumphant return and the establishment of his millennial kingdom.

The brilliance of Parley P. Pratt comes through in how he takes Joseph Smith’s narrative and develops it. Where Joseph Smith’s revelations and the Saxton letter quote or allude to phrases from the Bible, Parley P. Pratt will quote lengthy sections. While Joseph speaks and proclaims as a prophet, Pratt buttresses Smith’s words by exploring and defining who and what a prophet is and how the words of a prophet are unfailing. Joseph spoke of the Book of Mormon as a signifier of the gathering, while Parley adds the story of the book’s coming forth. Joseph’s revelations and (especially) the Saxton letter often read like transcripts of an extemporaneous sermon, while Parley’s work smacks of pragmatic rationalism, yet both present the same message—the Restoration is a reality. Voice of Warning would become “second only to the Book of Mormon as an instrument of conversion,” as well as a text viewed by outsiders as “on a par with the Doctrine and Covenants and the Book of Mormon.”[39] Joseph Smith may have lamented that Saxton would publish only a segment of his letter, but Elder Pratt ensured that this narrative would not dissipate quietly into the background of American religious history, and the Restoration narrative continues to be a fundamental facet of Latter-day Saint identity well into the twenty-first century.

Regarding the establishment of Zion, Parley P. Pratt wrote: "There is a city to be built in the last days, unto which not only Israel, but all nations of the gentiles are to flow." (Engraving by George Q. Cannon and Sons).

Regarding the establishment of Zion, Parley P. Pratt wrote: "There is a city to be built in the last days, unto which not only Israel, but all nations of the gentiles are to flow." (Engraving by George Q. Cannon and Sons).

Notes

[1] James B. Allen, “The Significance of Joseph Smith’s ‘First Vision’ in Mormon Thought,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 1, no. 3 (Autumn 1966): 45.

[2] Ross Anderson, Understanding Your Mormon Neighbor: A Quick Christian Guide for Relating to Latter-day Saints (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2011), 24.

[3] JS Letterbook 1:14–18, Church History Library. Background information and the quotations from the Saxton letter used in this essay are taken from Matthew C. Godfrey and others, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers, Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833, vol. 2 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee and others (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 350–55. The original is no longer extant, but it was copied by Frederick G. Williams into Joseph Smith’s letterbook, likely soon after the composition of the letter. Unless stated otherwise, original spelling will be retained throughout this essay.

[4] Letter to Noah C. Saxton, 4 January 1833, The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[5] Parley P. Pratt, A Voice of Warning, 93. All references from Voice of Warning come from the first edition printed by W. Sanford (New York: 1837).

[6] Terryl L. Givens and Matthew J. Grow, Parley P. Pratt: The Apostle Paul of Mormonism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 103–4.

[7] All quotations from the revelations of Joseph Smith are taken from Michael Hubbard MacKay and others, eds., The Joseph Smith Papers: Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, vol. 1 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee and others (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012); and JSP, D2.

[8] JSP, D2:106.

[9] JSP, D2:107.

[10] JSP, D2:104.

[11] Steven C. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2008), 19.

[12] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 51–52.

[13] JSP, D1:138.

[14] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 68.

[15] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 70.

[16] See JSP, D1:352; and Pratt, Voice of Warning, 68–69. It should be noted that while Pratt does cite Mark 16, as Joseph did in the Saxton letter, it isn’t in the context of the loss of the Holy Spirit but rather the establishment of the kingdom in chapter 3.

[17] These include the revelations now canonized as sections 6, 11, 16, and 18.

[18] See, for example, Pratt, Voice of Warning, 93–94.

[19] In revelations received after January 1833, the combination of “new” and “covenant” will occur eight times, all but one also including the term “everlasting,” and all found (with the exception of one instance in 131:2) in section 132. The one instance of “new” and “covenant” without “everlasting” is 107:19.

[20] The term “commandments” is somewhat opaque. Because “command” is often used synonymously with “covenant,” interpreting “commandments” as referring to the revelations seems the safer interpretation; however, the term could also refer to individual sections such as section 42. See Stephen E. Robinson and H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 3:54.

[21] Pratt uses the phrase “new covenant” six times, all in chapter 2, where he discusses the breaching of the “old covenant.” Pratt prefers the more New Testament–familiar phrase “Kingdom of God.”

[22] JSP, D2:352.

[23] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 112–13.

[24] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 119.

[25] JSP, D1:42–43 (D&C 10:48–49).

[26] See Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 113–14.

[27] Terryl L. Givens has written that “looking at the Book of Mormon in terms of its early uses and reception, it becomes clear that this American scripture has exerted influence within the church and reaction outside the church not primarily by virtue of its substance, but rather its manner of appearing, not on the merits of what it says, but what it enacts.” Terryl L. Givens, By the Hand of Mormon: The American Scripture That Launched a New World Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 63–64. Pratt’s treatment of the Book of Mormon in Voice of Warning would seem to support Givens’s observation.

[28] For a discussion of the reaction of early converts to the Book of Mormon, see Steven C. Harper, “Infallible Proofs, Both Human and Divine: The Persuasiveness of Mormonism for Early Converts,” Religion and American Culture 10 (2000): 99–118.

[29] JSP, D1:179 (D&C 29:7–8).

[30] JSP, D1:207 (D&C 33:6–7).

[31] See Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 125.

[32] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 60–61.

[33] JSP, D1:204.

[34] JSP, D1:203.

[35] Pratt, Voice of Warning, 176.

[36] See Pratt, Voice of Warning, 179–80; see “I would only add, that the government of the United States, has been engaged for upwards of seven years, in gathering the remnant of Joseph, (the Indians.) to the very place, where they will finally build a New Jerusalem; a city of Zion; with the assistance of the believing Gentiles, who will gather with them, from all the nations of the earth.” Voice of Warning, 185–86.

[37] Richard Kearney, On Stories (New York: Routledge, 2002), 88.

[38] Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, 142.

[39] Givens and Grow, Parley P. Pratt, 119.