Helping Children to Be Lifelong Learners

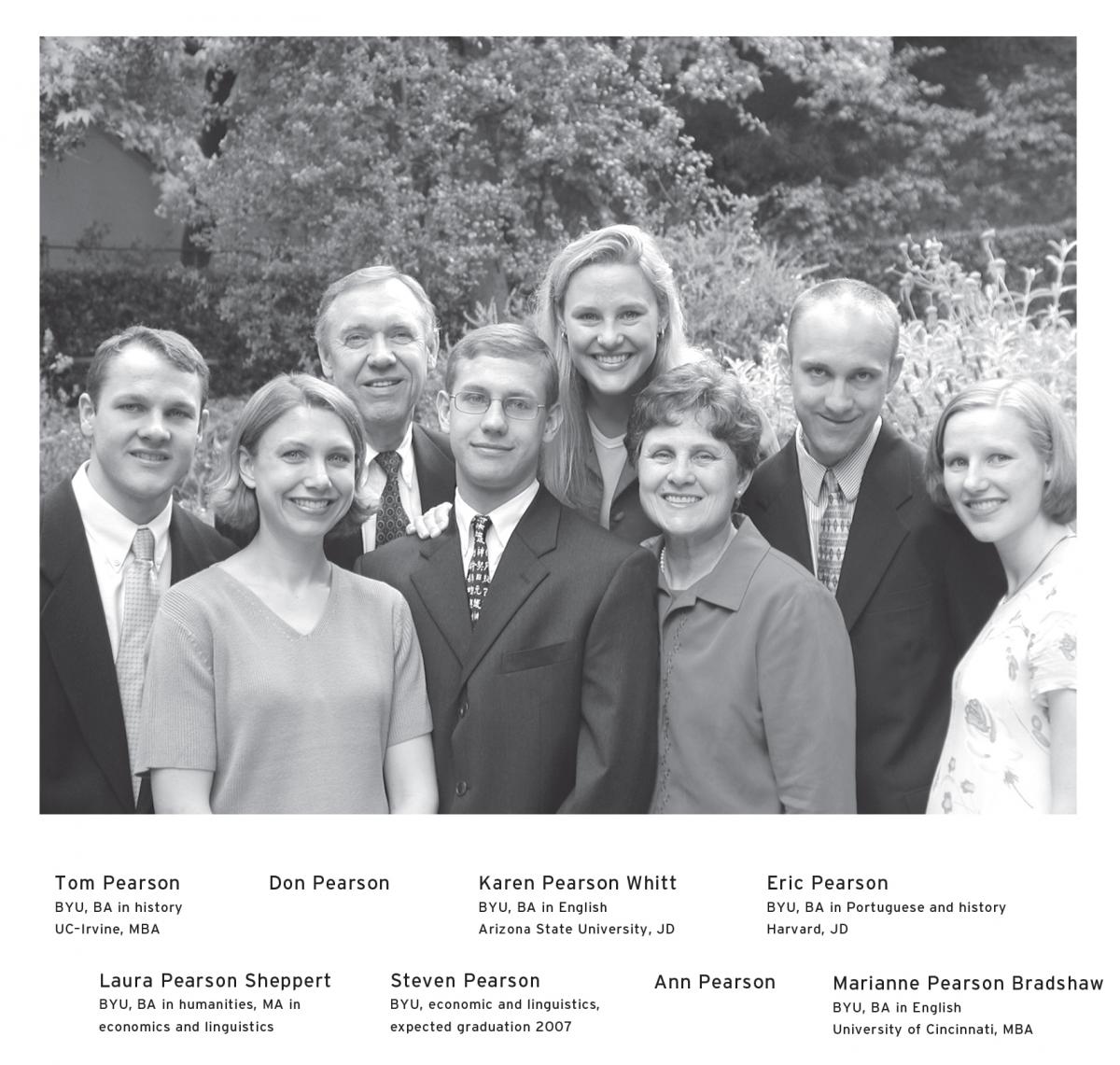

Ann Pearson and Don Pearson

Don and Ann Pearson, “Helping Children to Be Lifelong Learners,” Religious Educator 7, no. 2 (2006): 105–117.

Don and Ann Pearson are the parents of six children and live in Glendale, California. Both graduated from BYU, and Donthen received his law degree from Harvard University.

The Don and Ann Pearson family. Photo courtesy of the authors.

The Don and Ann Pearson family. Photo courtesy of the authors.

When our oldest son, Eric, was four, I was reading him a picture book, Paddy Pork and His Ballooning Adventures. I told the story from the pictures: “Paddy Pork is in a hot air balloon. He is landing on that island. He is dropping a line over the side of the balloon.”

Eric stopped me. “That’s not a line; it’s a rope.”

I looked at Eric and then back at the book and continued. “He is getting out of the balloon and trying to climb down the tree. Oh no, his coat is caught on a limb.”

Eric said, “That’s not a coat; it’s a jacket.”

I was somewhat annoyed and said, “Eric, there are no words in this book—only pictures. How can you tell that that is a rope and not a line and a jacket and not a coat? I am a lawyer and went to law school and now get paid a lot of money to make careful distinctions, and I can’t tell, so how do you know?”

He thought for a long time and then said, “Mother told me.” Of course, she had read the book to him probably a hundred times by then.

“Do you think your mother is the final authority in this house?” I asked.

His little lip quivered, and he carefully thought before answering, “No, you are.”

My chest expanded with this exceptional answer, but then, like the lawyer on cross-examination who asked one question too many, I asked, “How did you know that?”

He responded, “Mother told me.”

Although somewhat humbling, this experience caused me to reflect on the principle in the proclamation on the family that states “fathers and mothers are obligated to help one another as equal partners.”[1]

At the request of the Religious Educator, we have attempted to share some of what we have learned as parents and to outline some of our thoughts about education. The stories, experiences, and insights in this essay are our stories and experiences with our six children and are put together in an effort to give ideas that have worked for us. Most of the ideas are not groundbreaking, but they illustrate that “by small and simple things are great things brought to pass” (Alma 37:6).

Each of our six children has served a full-time mission, and each has graduated from college and has completed an advanced degree, except our youngest, Steven, who completed his undergraduate degree from BYU in April of 2007 and is currently planning to enter an MBA program. Sometimes people ask us, “How did you get your kids to do well in school?” The short answer is that we have been blessed with remarkable children. The long answer is (l) we loved learning and tried to be examples to our children of that love, (2) we read with our children and encouraged them in their reading, (3) we found opportunities for teaching and learning in day-to-day activities, (4) we were actively involved in discussions and decisions about education at every level of their schooling, and (5) we had dinner together as a family.

General Principles

We have found many ways to make learning fun for our family, including the following:

Share your love of learning. We like to tell our children the story about how we met as college students. Ann and I met in a New Testament class at Brigham Young University. Before the semester ended, we were studying together the great themes of the four Gospels. At the end of the semester, in preparation for the final exam, we enjoyed reviewing class notes together and creating outlines and memorizing key scriptures on baptism, service, and discipleship, among other themes. There was something fun about the intensity of the learning process and in preparing for the final examination. Learning was exhilarating, and studying together made it more enjoyable.

Over the years, we hoped that our interest in books and words and ideas would be so much a part of us that it would bubble out spontaneously. Our interest in world, national, Church, and local news is a part of who we are.

Spend time together. One of the greatest joys of being a parent is doing things with your children. We felt that time should be spent in a variety of different activities as well as in various combinations with family members:

parents and all the children together

mother one-on-one with each child

father one-on-one with each child

mother and father together with each child

In the last category, we planned one major vacation with each child during his or her growing-up years. What a wonderful interpersonal and educational experience for parents and child alike!

Take advantage of learning opportunities. Although there is no substitute for school, there is also no substitute for learning when school is out. Just as Alma taught that we should pray always in our fields and in our hearts, so we should be always learning from the daily activities of which we are a part. All of life is a learning process, and there are thousands of golden moments to teach and to learn. We used dinner time, driving time, and early morning time as bonus learning times by talking about subjects of interest and importance in our children’s schoolwork or scripture study.

Marianne recalls the time on the freeway when an understanding of fractions came to her. She was five or six at the time. The freeway sign said “Los Feliz—1/

2 mile.” We talked about what the “1” stood for, what the “2” stood for, and that for a mile with two parts, only one part was left until we came to the exit. I don’t know why she learned it on the freeway; it would have been easier at the dinner table to talk about half of an orange because it would have been so much more visible than half of a mile. When driving alone to or from work, Church, or business meetings, I listen to educational tapes or CDs, especially history and literature, or I listen to the scriptures. I recently listened to the Lord of the Rings trilogy. We have encouraged our children to use blocks of free time each week in meaningful ways.

Preschool and Elementary

Although there are preschool years, there are no prelearning years. It is obvious that babies and toddlers have dramatic learning curves. In advance of walking and talking, they see everything and they hear everything, and most, or at least much, of what they see and hear is retained.

The preschool and elementary years are an immense block of time. Even assuming a mission and graduate school, they represent half or almost half of all of the learning years that comprise a formal education. They are vastly undervalued and vastly underutilized.

A child under the age of twelve should have the opportunity to explore many interests and begin to develop many skills; however, we tried to be selective so that what was done could be enjoyed and done well. We tried to see that those early years were used to the maximum advantage, bearing in mind that we wanted balanced, happy children who had time to play, work at home, be involved in Church and sports, and still have time for themselves. For us, these activities didn’t include helping them find TV time or computer and electronic game time. When our older children were young, we kept our TV in a closet and brought it out only for special times.

- Show love. It is easy to love a child, especially your own child, and learning is helped by love. As a mother shows or tells a child the way to do something, her love is felt by her child, and that love reinforces learning. It also affects the quality of teaching; without love, the teacher’s interest in the learning process is not the same, and without love, the toddler’s interest in the learning process is not the same.

- Encourage independence. Each of our children learned very early how to say, “I will do it myself.” Learning is doing and then doing it again—not just watching and then watching again. No child or adult ever learned to play the piano by watching. Let them do it—whatever “it” is—as soon as they can. Find opportunities for them to serve others and meet challenges successfully through their own efforts.

- Celebrate achievements. The ultimate reward of learning is to have learned. But recognition from parents and others is a great motivator. Sometimes we would have a child repeat an Article of Faith or a scripture at family home evening and then present the child with a certificate for the accomplishment. “To Laura Pearson for learning the 10th Article of Faith.” “To Thomas Mack Pearson for counting to 100.” Presenting the certificate in a formal way at a formal meeting (family home evening) was fun. We often had the child receiving the certificate come forward and be lifted up on the table. He or she would be presented the certificate and congratulated. The award presentation would be formal and serious with shaking hands and a hug and sometimes a picture. The certificate and picture, if a picture had been taken, would then be placed on the refrigerator door.

Make reading fun. The ability to read is the foundation of all learning. The key is practice, and practice should be fun. We tried to be sure the child was practicing at the right level so that it could be fun.

We did not set out to teach our children to read before formally learning to read in school because we wanted their school experience to hold some excitement. But we did want them to be prepared to learn to read when that time came. As they asked about letters and words, we found it natural to help them learn the alphabet and the sound each letter makes. The first word a child wants to learn to recognize and write is his or her own name. As we read to our children and as they looked at cereal boxes, toys, and games, they discovered letters and then words. Group scripture reading was a time when our beginning readers took great joy in finding and marking words they recognized in their own copy of the Book of Mormon.

As we drove in the car, we would point to a sign and ask, “What is that letter?” or “What sound does that letter make?” Sometimes we played the alphabet game (finding the alphabet letters in order from A to Z on road signs). Older siblings love being on a team with a younger brother or sister who can’t read but can recognize letters. Thus, words were presented as a natural part of daily living (and it helped to pass those long minutes driving older siblings to baseball practice or piano lessons).

The very most significant tool for parents in helping young children develop reading skills, prior to their being able to read themselves, is reading aloud together. Reading books is interesting and fun. Good stories are imaginative and informative. Bedtime was the most regular time for reading aloud in our family.

One night when Karen had just turned two, her older brother and sister had been permitted to spend the night at cousins, and I was helping her get ready for bed. I turned out the light and gave her a bottle. She refused the bottle and said, “Prayer, brush teeth, story!” Each child felt entitled to his or her bedtime story, and after it was read, they asked to “please read it again.” And that is what we wanted them to say—we wanted them to fall in love with books. We cherished this time, free from distractions, when we could nestle together and share the wide world of life’s experiences through books and the discussion they inspired.

Even well into the elementary years, each child chose a book every evening. Sometimes an older child would do the reading to a younger one, but the child always wanted a parent nearby to appreciate the reading and to be a part of that bedtime ritual.

We enjoyed reading to our children. We enjoyed listening to them read out loud to us. We enjoyed reading together by taking turns in the same chapter of scriptures or a book or short story. We read Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer after dinner over a period of weeks. It was fun. Karen remembers that she could hardly wait for dinner to end so we could reach the next part of Tom Sawyer. Reading should be fun. It should be informative. It should be exciting. Every child should have the experience of reading a book that he or she cannot put down. We tried to help our children find that book.

Before leaving elementary school, a child should be able to read well. It doesn’t make any difference what else is covered in the curriculum at this level if a child comes away with inadequate reading skills. When one of our children was struggling with a skill, we made it a goal to work on it at home with charts and prizes and extra coaching. One daughter decided in the sixth grade to relearn the way she held her pencil to improve her penmanship. We rewarded her efforts, and after several months of practice, she was pleased with her new style and was comfortable in writing.

Our children enjoyed a formalized learning time at home in their preschool years and during the summer in later years. To them, it was fun. To their mother, it was easier to keep the children happy. I went by the philosophy that little children are happiest when their hands are busy and their tummies are full (the philosophy works well for teenagers and fathers too).

We were blessed to have other families nearby who felt the way we did, and the children had many group activity times in each other’s homes, which made it more fun for them and alternately freed up the mothers. One summer our family and another family combined to study transportation. We read, created, wrote, and then rode as many things as we could arrange to ride.

Laura remembers spending one summer putting together her alphabet book. There was a section of the book for each letter, and in that section there were pictures and objects cut out from magazines and newspapers whose name or description started with that letter.

Help children to be precise in their thinking and use of words. We tried to help our children learn at early ages to be precise in their use of words, and to distinguish between words and meanings. When Eric was three or four, I asked him one Sunday after church, “What did you talk about in class today?” He responded, “I didn’t talk about anything.” When I asked him what his teacher talked about, he responded with some detail that she had talked about the blind man whom Jesus gave a blessing and healed.

Later, our hamster died. We dug a grave out in the canyon and as we walked back to the house we discussed how the spirit leaves the body when a person or animal dies. I said, “Now that the grave is ready, let’s go get the hamster.” Eric responded, “You mean the hamster’s body.”

Laura liked to talk on the telephone when she was four years old. So Ann had to explain that you could not just talk on the telephone at any time, but only when you had something really important to say. Moments later Laura was back on the phone. Ann explained that she had just been told not be to the phone unless she had something important to say. Laura said, “Mother, I was telling my friend Rena to keep the commandments!”

Learning to make careful distinctions is an important skill and can be understood by young children.

Teach numbers and math concepts. Counting is a great activity wherever you are. We counted the number of motorcycles or the number of red cars or big trucks or, as the children got older, out-of-state license plates. This activity also taught the important skill of making distinctions: What is a red car or a big truck? Where is Wyoming? These are wonderful discussions for a child about to enter school or already in school.

Concepts of addition and subtraction are also easy to develop within almost any daily situation. How many friends can you invite to our house? How many plates do we need to put on the table for dinner if everyone in our family is here? How many more if Grandmother and Grandfather come for dinner?

Following a recipe, measuring and cutting, using money, playing board games, timing a jog around the park, reading music, and participating in many more activities of daily life provided some of the meaningful and fun learning experiences in our home. And so, as with reading, understanding of math can be developed naturally. Practice can become a game, and deficiencies in ability should be met with extra help, practice, and rewards for persistence.

Allow children to teach. Our children enjoyed playing school. When school ended after Marianne’s fourth-grade year, she started a summer school for neighborhood children. This school included her two younger brothers, Tom and Steven, who were ages five and three at that time. However, her students were generally ages four to six. She had a two-hour school three mornings a week for six weeks and continued this for five summers. What a powerful experience for her—not just in teaching but in organizing, disciplining, and keeping the attention of a roomful of little boys. She also had to collect what she was owed from the parents of the students attending. Ann was always in the house to oversee things, but it was Marianne’s school.

Every child needs a turn to be a teacher. It opens a different vision of both teaching and learning. The direct benefits of learning what you are required to teach is obvious to all parents.

Use summertime to advantage. The summers were a wonderful time to for our children to advance at their own pace and interest. But summer charts kept them focused on their responsibilities at home (chores and household tasks) as well as on fun activities (parties, playing with friends, and sports) and learning opportunities (reading books and scriptures and engaging in school-like study). Items on the charts were checked off for the day, week, month, or summer, and the children were rewarded for having completed them.

Our children liked this system so well that they requested summer charts well into high school, and they continue to create them for their own children today. We discovered that a significant key to their success was having them ready to go the first week school was out while the children were still used to an early-morning routine.

Junior High and High School

As the children grew older, they could tackle more difficult tasks. During grades seven through twelve, formal education became more demanding of a child’s time and focus.

Develop writing skills. Eric came home in tears one day from junior high school. He had an assignment to write two pages about himself. “I don’t know how to do this, and I can’t do this, and that stupid teacher shouldn’t ask us to write two pages about ourselves.” The more he thought about it, the more miserable he became. He was unwilling to make notes or an outline of what he wanted to write.

Finally, I took out of my briefcase the dictating equipment that I use at my law office. The equipment is small and can be held in one hand. I showed Eric how to work it. Then, I said, “Now, just tell me about yourself with the ‘record’ button on.” When he was finished, we typed it. Then, we discussed how it should be changed to say what he wanted to say. He learned that he could write something meaningful.

I don’t think he (or anyone) finds writing easy, but I can’t recall him saying again about a written assignment, “I just can’t do that.”

Some parents and students say, “Don’t take that class because the teacher is so demanding. You have to write a lot of papers.” Ann and I would say to our children, “That sounds like a great class. You will learn a lot.” And if you have to write, you do learn a lot. There is no other way. Good writing is good thinking on paper.

We hoped that each of our children would have one or more teachers in high school who were truly fastidious about papers being grammatically correct. Spelling must be correct. Subjects and verbs must agree. Pronouns must have an antecedent. Punctuation must be correct. Poor quality in English presentation is as bad as poor analysis and makes good analysis almost impossible to see. The very best of ideas sandwiched in between poor grammar and misspelled words will likely be lost on the reader (and grader).

Have high expectations. Marianne related an experience that she had in the seventh grade. She received a C on the first test in her English class that fall. She was afraid to tell us but did so. She said that we reacted calmly (not what she was expecting), saying, “Marianne, we think you can do better than that, and we will help you.” In this literature class, the assignment was to read one short story each day. Ann or I would also read the story and discuss it with Marianne. She remembers that we showed her how to make notes about each story’s characters and plot. We reviewed her notes with her in preparation for the next test. She received an A on it. This experience increased her confidence and taught her a study strategy that she has used and reused since. We somewhat dropped out of seventh-grade English for most of the rest of the year, except for when something was just too interesting not to read and discuss with her.

Children almost never perform above the expectation. If a son or daughter believes a B is his or her best, it usually will be. Balancing expectation and approval of the performance given is sometimes a challenge. We have always said to a child: “If that is your very best, that is all we ask of you. We are proud of you and your hard work.”

Encourage wise class choices. The question, “What classes should I take?” is asked by students every year. A high-school student who is serious about college preparation should take classes each semester in English, mathematics (including computer science classes), history, science, and foreign language. Such a schedule will prepare him or her well. Such classes help develop critical thinking skills, which ultimately is what good education is about.

There is no substitute for good English grammar and usage. History and other subjects, as well as English literature, all require careful reading, analysis, and writing in English.

There is no substitute for math. Ideally, a student will have completed in high school at least precalculus and one calculus course. For many college graduates today, the last math class they ever took was in high school. To complete high school with calculus requires a math class every semester.

In today’s world, computer skills are critical and are a foundation on which communication in humanities, business, and all disciplines build. History is fun and essential to a good humanities background. Sciences should include biology, chemistry, and physics. Language has many purposes, not the least of which is to strengthen and improve English. Latin especially helps students to understand English language structure and to improve vocabulary significantly.

Encourage personal discipline and study skills. Participation in music, athletics, and early-morning seminary requires that a student learn personal discipline. High school becomes a crucial time of decision as children need to focus their time to a greater degree on the things they want to do the most. Choosing those things should be a matter of discussion and prayer.

Our daughter Karen participated in sports in high school and was active in student government and seminary. How did she do it and maintain a high level in her academic studies? She says that athletics and school and Church activities did not cause her to underperform academically. The challenge required her to focus and use her study time wisely. Athletics, music, seminary, student government, and other similar time demands need to be balanced.

It was important to be sure their schedules were not too full. Overscheduling is as bad as or perhaps even worse than underscheduling. High performance in four or five classes is better than mediocre performance in six. A high GPA is essential for good college opportunities, but it is more critical for a student’s self-assessment. If a student is getting A grades and has that expectation, then that is the level to which the student performs. If a student is getting B grades but there is an A level of expectation, neither the student nor the student’s parents are happy.

Sometimes in high school (as contrasted with college), taking fewer classes is not a choice. The school may require a certain number of classes and may allow one study hall but not an option of two. Then, reducing the number of honors or AP classes may be the only way of balancing the intensity.

Occasionally, other students in our stake will discuss their schedules with me, and I often find them to be intense and wonderful schedules. But when I ask if they will have sufficient study time to prepare for their classes, I find they are working fifteen hours a week and have sports or other significant extracurricular activities. It sometimes seems to me that it will be impossible for them to perform well in all of the classes they are planning to take. I do not think it is possible to perform at a high level in difficult classes with inadequate study time. It would be better to drop one or more classes and have time to prepare well for those remaining.

We are not much on study-skills classes, but we are high on study skills. It is mostly discipline, and it is a lot about getting started in a good location. That is why we like a free period in the library at the school.

- Schedule free periods of time. Sometimes study at home is more difficult to start and more difficult to maintain. If it is late in the day after athletics, the body and mind are tired and have less focus and energy. If the school permits or requires a free period or periods during the day, that is wonderful (in college, you can design your schedule with free periods in between difficult classes). Free periods are a great opportunity to prepare for the next class or classes and to prepare for tests later in the schedule that day, as well as for a desired change of pace for the body. When well used, they permit a burst of academic energy during that hour. Students should be certain to select a study spot in the library where they can concentrate and be effective. This is not a social hour and should be one of the best study hours of the day. It can be used as preparation time or for a final test review, and it will reduce late-night studying. When advising my children, I preferred to see that free period in middle of the day’s schedule where it can be truly valuable. Neither the first nor last period of the day is nearly as valuable.

Prepare for the SAT/

ACT . The SAT and ACT are extremely important because they are critical to college admission decisions. They are important for a student’s academic stature in high school, too. They are critical for scholarships and high-school graduation awards.Practice is most helpful. The argument that these tests are so broad that there is nothing anyone can do to prepare is simply false. First, taking practice exams is absolutely essential to understand how the test works, what counts and does not count, or when a guess hurts or does not hurt in the overall score. Second, a good math review is substantive and can refresh skills in areas that will be tested. Practice review will not make up for algebra or geometry classes that have never been taken, but it will sharpen the knowledge of those and related subjects for the test. Practice tests will not likely strengthen vocabulary significantly, but the practice tests will help students know the format and be familiar with the types of questions and analysis to be expected. Practice applies to the PSAT too; the better the PSAT, the better the SAT will be.

We have found short one-on-one paid SAT review courses expensive but worthwhile. It helps to have someone other than the parent working with the student and moving the SAT review forward. Having a schedule is an important benefit, as is having someone working with the subject material and with other students in preparation for the exam on a regular basis.

- 7. Take advanced placement classes and exams. It gives great freedom to a college schedule to have a number of credits from advanced placement. Students should not hesitate to challenge exams for which they think they are qualified but haven’t taken the advanced-placement class. Sample questions from past tests and study books are available to help with challenge decisions. Laura studied music theory as a part of her ten years of piano lessons and state certification program. With some additional review prepared by her piano teacher, she was able to pass the music theory exam. Steven chose to prepare for an advanced-placement exam as a part of an independent study class during his senior year.

Use materials outside of high school. Steven was required to have credit in art to graduate but didn’t want to give up an academic period to take the class. Instead, during the summer before starting twelfth grade, he took Art History 101 online for credit from BYU. He received college credit, and the class was accepted for his high-school graduation requirement. BYU has many outstanding online classes, both at the high-school and college levels. They are worth considering, especially in the summer.

Students should be able to get an A in an online class, as they can retake the quizzes and sometimes the exams for a fee. Our only rule for the children was that they must have completed the online class they were taking before starting another online class.

Use summers meaningfully. During their high-school years, we hoped our children would have a unique educational or work experience during the summers. Fortunately, we didn’t find it necessary to use summers to catch up on core academic subjects. After seventh, eighth, and ninth grades, they occasionally used summer classes to accelerate in math or language. Good work opportunities in our community are limited for their age. Tom and Steven both took Algebra II in summer school, which permitted them to start precalculus a year earlier and take additional math and computer classes before they graduated. Because of earlier language background, Steven took Spanish 2 one summer, which permitted him to start Spanish 3 in the ninth grade. He spent the summer after ninth grade living and going to school in Chile. This experience made a huge difference in his Spanish conversation skills.

Laura and Marianne were exchange students with American Field Service, Laura in Turkey and Marianne in Argentina. These were interesting and very broadening experiences. Perhaps we are too protective, but there were aspects of their experiences that were a little frightening. Steven’s experience in Chile, where he lived in two different Latter-day Saint homes, was much more comfortable for us. Karen did a “People to People” exchange tour program in Russia and Scandinavia. Living in a foreign country was a great experience for each of our children, and created a wonderful, powerful appreciation of the United States of America.

Teach children to make good choices. Great scholastic training without good common sense still leaves us short in life’s journey. We tried to involve our children, when appropriate, in helping us exercise good judgment as parents and also to trust in their judgment. One of a high-school student’s most significant decisions is which college to attend. We encouraged our children to consider applying to several schools. We discussed with them questions concerning these choices, such as “Where will you receive the best educational training?” “Where will you meet the most friends and form lasting, lifelong friendships?” “Where will you enjoy college the most?”

One of our trips was a BYU Travel Study tour of Mexico and Guatemala with our middle daughter, Karen. One evening we went out to eat at a restaurant in Guatemala City. We had been seated, and we ordered. Immediately after ordering, Karen said she was impressed that we should not stay at that restaurant. We called the waiter and apologized that we were canceling our order and would need to leave. Neither of us remembered this incident in detail, and when Karen told this story recently, we asked her what happened. She responded, “I don’t know what happened at the restaurant or what would have happened to us had we stayed, but I will forever remember that my parents would act on my impression alone. You said, ‘Karen, we don’t have those same impressions, but if you have an impression that we should leave, then we should leave.’”

Conclusion

We can summarize our strategies very succinctly: Love learning. Do things together and use learning opportunities in day-to-day activities. Focus on basic reading skills. Finally, be involved in the classroom content with your son or daughter, not just the extracurricular activities. By getting involved in everyday learning activities, parents will have some great experiences with their children and will set them on the course to becoming lifelong learners.

Notes

[1] The Family: A Proclamation to the World,” Ensign, November 1995, 102; emphasis added.