I See You, God

John S. Tanner

John S Tanner, "I See You, God," Religious Educator 20, no. 2 (2019): 23–37.

John S. Tanner (jstanner@byuh.edu) was president of BYU–Hawaii when this was written.

Address at the Wheatley Institution’s fall 2018 Reason for Hope Conference, 29 November 2018.

Disciples long to greet Jesus and to embrace him and to be embraced by him.

Disciples long to greet Jesus and to embrace him and to be embraced by him.

Aloha! I am both honored and a bit daunted to be invited to speak to you about the reason for the hope that is in me. The topic seems to call for a talk in a personal vein. So I shall speak autobiographically about the reasons for the hope I felt as a young man preparing to go on a mission and for the hope I feel today. I also will touch upon larger epistemological questions about how I know. I have entitled my talk “I See You, God” for reasons that will become clear later.

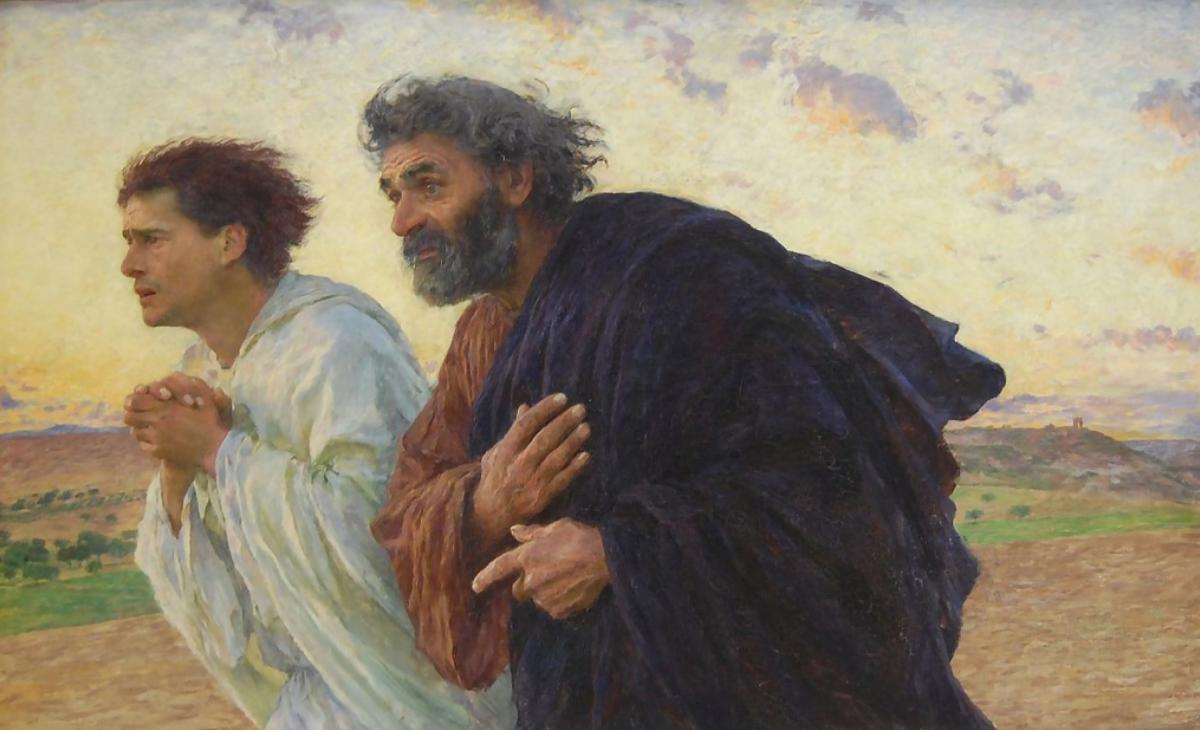

Let me frame my remarks with a painting that I love by the Swiss artist Eugène Bernard that was painted in 1898. The title is The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning of the Resurrection. To me, the painting is a marvelous study in hope.

A large copy of Bernard’s painting hangs on the wall of my office in Hawaii. A smaller one hung in my office here at BYU for many years. It was a gift from Bruce Hafen when he left BYU. In a way, it represents gifts of faith I have received from so many here at BYU. I owe a debt of gratitude I can never repay to teachers, colleagues, roommates, students, and friends at BYU who have provided reasons for hope. Like John and Peter, you have pressed forward in faith, hope, and love for the Savior. Your example has inspired me do the same.

I love that the artist focuses on the disciples before they see the empty tomb or the risen Christ. Bernard has chosen a very human moment from the Gospel of John for the subject of his Easter painting. The disciples stand in the story where we stand in history—namely, on this side of Christ’s return. They, as we, lean into the dawn, full of hope, expectation, and love, but not having yet seen the risen Lord. Having heard about the empty tomb from other witnesses, they press forward in hope to see for themselves. They long to greet Jesus, whom they have loved, however imperfectly to embrace him and to be embraced by him.

As do I! This is my fondest hope. I too long to embrace and be embraced by the Savior. I am reminded of such a promised embrace at some future day each time I participate in the temple endowment. In the meantime, however, I “press forward” like the disciples on Easter morning, “having a . . . brightness of hope” in my heart and trying to endure to the end (see 2 Nephi 31:20). I see images of the hope in these two figures. In John, I see an image of myself as a freshman student at BYU, full of hope and youthful idealism. In Peter, I see an image of myself now, full of hope and of years.

Before attempting to explain reasons for my hope then and now, I must offer one crucial caveat. I do not hope to articulate here all the reasons for the hope I feel. And even if I could render all my reasons into words, this would capture only part of the fullness in my heart. My testimony is not coterminous with the reasons for it. My hope in Christ feels and is bigger than any reasons I might adduce for it and more enduring than the shifting reasons that have undergirded it over the years. I confess with Pascal that “The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of. . . . We know the truth not only by reason, but by the heart.”[1]

So, with this crucial caveat on reason and hope, I shall now try to channel the hope I felt almost fifty years ago as I was trying to decide on serving a mission. But first, I need to go back even further to give you glimpses into my spiritual life as a boy and teenager.

Eugene Barnard, The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning on the Resurrection.

Eugene Barnard, The Disciples Peter and John Running to the Sepulchre on the Morning on the Resurrection.

Reasons for Hope in My Youth

Some people say that they have never doubted. I cannot say this. But I can say that I have always believed.

As long as I can remember, I have believed that I was a child of God. I can’t remember a time when I did not want to be good or when I did not feel bad when I was not.

I remember once weeping in a closet for my sins when I was just a boy. I also vividly remember feeling clean and pure after my baptism when I walked out of the Pasadena Stake Center. As I emerged into the open air, I felt God’s love envelop me. Heaven seemed as real and close as the nearby San Gabriel Mountains.

At fourteen, I had an experience with the Spirit that shaped my life. One Sunday in August, Dad called all his children together and gave us each a father’s blessing. The spirit of revelation in the room was powerful, almost palpable. This experience with revelation marked me and all of us who were there. For me, it became a sort of Sacred Grove experience—a spiritual experience that I couldn’t doubt even when I doubted everything else.

I think the Lord knew I would need such a Sacred Grove because as I grew my questions grew. I had a strong need to question everything. I had to know for myself that what I had been taught was true.

And I began to worry about big questions, like the problem of evil. As a teenager, I was affected by the movie Judgment at Nuremberg, especially pictures of the death camps. Also, my high school German teacher was a German Jew whose family had been killed in the Holocaust. Well into my adult life, I was preoccupied with the Holocaust. I still am. I once told my sister that not a week went by without my thinking about the Holocaust.

I came of age during the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement. A child of the sixties, I wrestled with the social issues that were roiling the country at the time.

As a teenager, I also wondered about issues of cultural relativism. Some of my questions were prompted by a social studies teacher, a grad student from UCLA in anthropology, who had us read Margaret Mead.

Gratefully, my Young Men adviser was also a grad student; he was getting a PhD at USC in philosophy. We talked about Descartes’s “dubito ergo sum,” mind/

I came to BYU full of both faith and questions. I thank God for BYU. Here I found people with whom I could have serious, gospel-informed conversations about ideas and issues. One of these people was Dale Lambert, a returned-missionary roommate I had when I was a freshman. Dale became like a wise older brother. A member of the BYU debate team, Dale had a sharp mind as well as a strong testimony. I still remember a Sunday School lesson he taught on 3 Nephi 17. He spoke about Jesus healing the sick, lame, and blind. What made the lesson so poignant was that Dale was himself a victim of childhood polio who used crutches.

I also remember President Hugh B. Brown’s devotional talk during the spring of my freshman year, entitled “An Eternal Quest—Freedom of the Mind.” It was a welcome affirmation of the life of the mind in what I sometimes found to be a narrowly rigid campus climate. What most touched my heart, however, was not the topic of the discourse but President Brown’s closing testimony. I remember feeling carried away on the wings of the Spirit as I left the fieldhouse—perhaps a bit like John in the picture.

I offer this self-portrait as prologue to describing a spiritual crisis at the end of my freshman year. The crisis was generated by the decision I was facing that summer as to whether or not to serve a mission. Everyone expected me to go. They thought it was an easy decision for me because, to all outward appearances, I seemed a devout, orthodox, even pious, young Latter-day Saint—much like John in the painting.

But the decision was anything but routine or easy for me. What daunted me was not the prospect of a two-year mission. It was eternity. Specifically, it was the temple endowment. I saw the endowment as requiring me to stand in a holy place and there say before God and the world that this is what I believe and shall believe for the rest of my life. This seemed overwhelming, too much to ask of an eighteen-year-old who was still forming his own philosophy of life. It meant, to me, that I could no longer be spiritually hesitant or hold my beliefs provisionally.

My sister Athelia told me that I had already made an eternal covenant at baptism, so making a temple covenant did not put me in a fundamentally different position. Perhaps so, but the prospect of a temple endowment felt so much more solemn and binding. I now had to take a stand as an adult.

So I prayed and pondered, pondered and prayed all that spring of 1969. I remember on Sundays walking around the south end of campus near where I lived, my heart stretched out to God to help me know, really know. I even found places to pray in the bushes on the hillside. I don’t know what I was expecting, but I knew that I had not seen a vision like Joseph Smith. And, although I held the Aaronic Priesthood, no ministering angels had appeared to me. How could I take upon myself the oath and covenant of the Melchizedek Priesthood? Did I know enough? Not enough about the gospel. But did I know with enough certainty that the gospel was true, such that I could tell others to stake their eternal lives on the truth of the restored gospel? That was the question.

In the midst of this spiritual turmoil in the spring of 1969, I attended the inaugural Festival for Mormon Arts. There I saw a painting that spoke to my struggle. It helped me decide that I did know enough. The painting was called I See You, God.

I did not know who the artist was until just two weeks ago when, after some research, Gordon Daines of BYU’s Special Collections discovered that it was James Christensen. I want to take this opportunity, with his widow in the audience, to thank James. I wish I could have done so in person before he died. This early piece, which I learned was not the painting he originally intended to execute for the festival, helped a freshman student realize that there are other ways to see God than with the eyes. It is possible for the hand to “see” God by feeling the light through what might be called a sort of spiritual synesthesia, although I did not know the word synesthesia at the time. The painting helped me realize that there are many ways to see God, and that I had had “seen” God with senses other than sight.

James C. Christensen, I See You, God (1969).

James C. Christensen, I See You, God (1969).

The painting was so important to my spiritual journey that I used it in my farewell talk to explain my testimony. I don’t have a written text for any talk I gave in my youth because in my family we never read our talks. But my dad evidently recorded my farewell talk and had it transcribed for my brother in the mission field. As a result, I have a transcript. This allows me to describe with considerable accuracy reasons for the hope that was in me as I left on my mission almost fifty years ago. Let me share these reasons by summarizing and occasionally even quoting from my farewell talk.

I first described the painting. I explained that the jumbled objects at the bottom of the picture to me represented the world, while the hand expressed our strenuous striving to reach up to light, to God. Then I focused on the title I See You, God, which was what most intrigued me. “It seems obvious to me,” I said, that “you cannot see with your hands. There are no optical nerves in your fingers.” So “when the artist entitled the painting I See You, God, he was using the word ‘see’ in a broader sense,” meaning something like perceiving. In the same way, when we say “seeing is believing,” we really mean perceiving is believing.

Then I gave this example: if I stick my hand over some source of heat, I cannot distinguish whether it is a flame, or a hot rock, or a welding torch. I can’t determine what only my eyes could perceive—namely, that it is light. But I can feel warmth and know something is there by its warmth. So, too, the hand can perceive the warmth of the light as it’s reaching up to God. In the same way, we also are able to perceive God by the warmth of the Spirit and say as the artist did, “I see you, God. I feel your presence and know you are there.”

Then I said, “I feel that in my lifetime I have also seen God, not literally with my physical eyes, but I have felt his Spirit and his presence in the same way the hand sees God.”

And I bore my testimony of three areas where I had seen God:

First was in the fruits of the gospel, especially as I had seen these fruits in my family. I called this “pragmatic” evidence, meaning that I had seen the gospel work.

The second was in my mind through study, especially my study of the Book of Mormon. I said, “I would like to take this opportunity to bear testimony on the Book of Mormon. Probably the most important thing I did last year at school was to read the Book of Mormon every day.”

The third was through the witness of the Spirit in my heart. I said, “This is the thing that has helped me over the crises of this summer as I have been cynical and doubting my faith. When I have been close to the Spirit, somehow my life was brighter, my life was more enlightened.”

To illustrate how I had felt the Spirit and knew it was real, I quoted from and commented fairly extensively on Alma 32. I said that I had felt the seed of faith expand in my soul and enlighten my mind in a way that was discernible and real. The line that especially struck me was “O then, is not this real?” (Alma 32:35). I testified that these experiences with the Spirit were very real to me. The Spirit “is a real thing that you can discern, just the same as the hand in the picture could determine when it was under the influence of the world or when it was feeling the warmth of the light.”

I concluded by saying that, like the artist, I hoped someday to actually touch the light and be able to say, “I know you, God.” Meanwhile, “this is the testimony which I bear, that though I have not seen God with my literal eyes, I have seen him with my heart, and as the hand reaching up felt the influence of the light, I too felt the influence of his light. I have felt it in my family, I have felt it in the study of the scriptures, and I have felt it in myself. And I leave this testimony with you in the name of his Son, Jesus Christ.”

After nearly fifty years, I have continued to see God in these ways and bear this same testimony about the reasons for the hope that is in me. I have not had a face-to-face experience with God on the top of Mount Sinai, but I have stood on the slopes of Sinai and felt his presence there.

From John to Peter

Now, let me turn from my freshman self to my adult self—from John to Peter, as it were. As an adult, I remain even more full of conviction, but I still have questions too. I realize that it says in Lectures on Faith that faith and doubt cannot exist in the same heart at the same time, but this does not feel like the way I have experienced faith. The light of faith that burns in my heart seems to run on an alternating current. I have long identified with the father in Mark 9 who cried to the Lord, “with tears, Lord, I believe; help thou mine unbelief” (Mark 9:24), and I am persuaded that this is the cry of a believer.

This detail appears only in the Gospel of Mark. Biblical scholars associate the Gospel of Mark with Peter. I like to think that Mark includes this detail because he heard his companion Peter tell it many times and that it spoke to Peter’s sense of his own weaknesses and failings until he finally emerged as the unshakable rock we see in Acts.

When I see Peter in Bernard’s painting, I see a man with hope in his eyes, like John, but something more as well.

I see the face of a believer weathered, wrinkled, and worn with experience. I see the face of a disciple who has looked deep into his own soul, like Rembrandt in one of his self-portraits as an old man. I see the face of an Apostle eager to meet the Master but also aware that he thrice denied him since last they met. It is the face of one who loves Jesus so much that he is willing to suffer rebuke if that is what is required to be again in his presence of his beloved Lord. I see myself.

I see a wrestler. In Greek the word for “wrestle” is agon, from which we get “agony.” Bernard’s Peter belongs in the company of agonists like Jacob, who crossed a ford named Jabbok for an enigmatic night wrestle. Jacob names the site of his wrestle “Peniel,” meaning the face of God (Genesis 32:30). Like Jacob, many believers have come face-to-face with God through agony. Many have emerged different persons from the struggle, as Jacob became “Israel,” which may mean one who has wrestled or contended with God. (Hence, to belong to the house of Israel is to belong to a family of spiritual wrestlers!) We read that Jacob was wounded in his night wrestle. He may have limped back across the ford Jabbok to face his brother. So too in the gospel narrative, Peter does not run as fast as John. And his gaze may not be as purely beatific as is John’s in Bernard’s painting. But his are also the eyes of a believer. And he runs as fast as an older man can.

I am drawn to figures like Bernard’s Peter—people who, as my daughter likes to say, understand the human experience. I don’t claim to have struggled so agonizingly as many have, but I have thought about, written about, and taught about spiritual wrestlers all my adult life. This has been a flood subject for me.

I have written about Jacob’s wrestle. I have also published many—perhaps too many—pieces on the account of another Old Testament agonist, Job. I am drawn to the book’s timeless and timely questions, questions as old as time and as fresh as today’s headlines. I have written and lectured on sonnets of spiritual struggle by John Donne and Gerard Manley Hopkins. I have composed songs based on Nephi’s psalm. My book about Søren Kierkegaard and John Milton—spiritual wrestlers both—is entitled Anxiety in Eden. And the poet I most resonate with is George Herbert, who described his devotional poems as a record of “the many spiritual conflicts that have passed between God and my soul, before I could subject mine to the will of Jesus, my Master.”[2]

I feel a kindred spirit in Herbert. Dostoevsky remarked that his hosanna had been forged in an enormous fire of doubt.[3] My struggles have been less with questions of doubt, like Dostoevsky’s, than with the quest for complete discipleship, like Herbert’s.

Now, all this might create the misimpression that my own adult spiritual experience has been principally one of struggle. This would be incorrect. I have known much more of grace than of agony. My spiritual life as an adult has been spent far more in sunshine than in shadow, more on the mountaintop than in the valley. I have often, very often, felt to exclaim as did Peter on the Mount of Transfiguration, “Lord, it is good for us to be here” (Matthew 17:4). Many experiences that provide reasons for the hope that is in me are too sacred and intimate to share. But let me share one brief, unbidden moment of grace to illustrate countless others.

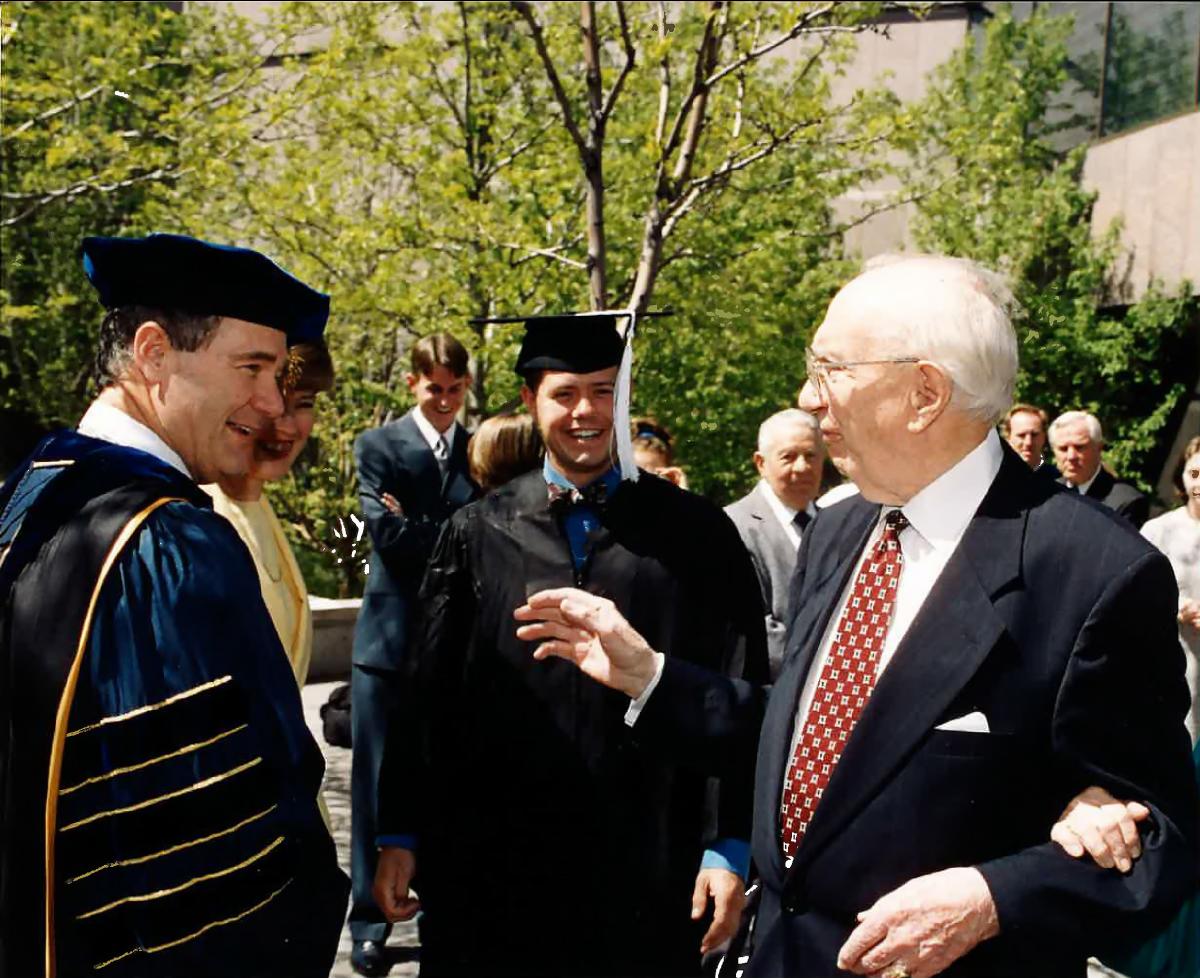

It occurred at the graduation from BYU of my oldest child, Jonathan. We visited briefly with President Hinckley. The BYU photographer Mark Philbrick happened to snap a photo of the meeting.

Now, I had met and conversed with President Hinckley a number of times before. So I was completely unprepared for what happened when I shook his hand at the graduation. I felt something like an electric shock course through my body, bearing witness that he was a prophet of God. It was a very brief but thrilling experience that, as I said, remains one small but sweet and vivid reason for the hope that fills my heart today.

So do I have questions? Of course! Some questions, like the question about seemingly inexplicable and disproportionate suffering, are never solved once and for all by abstract answers. Heaven has a habit of pitching existential curve balls to Saints and sinners alike. Hence, prophets hurl back to heaven the perennial questions, “O God, where art thou?” and “O Lord, how long?” (Doctrine and Covenants 121:1, 3; 109:49). And even the Son of God interrogates his Father with the soul-searing question, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?”—a cry from the Psalms so astonishing and so agonizing when wrung from Jesus’s perfect heart that the Gospels preserve it in the original language: “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” (Matthew 27:46; see Psalm 22:1). Surely, if Joseph and Jesus had questions, we should not be surprised that ordinary Saints like you and me should have them. For are we greater than the Master of the Universe that we should have no questions!

But with the years, my questions have become enveloped ever more deeply in my convictions. Alma counsels us to nourish the “desire to believe” (Alma 32:27). I have tried to do this by cultivating the seed of faith until it grew into delicious fruit. Similarly, my wife, Susan, has encouraged us to engage in this process of nurturing faith by choosing to believe. I am grateful for her testimony, which burns so brightly that I have often warmed my hands by the fire of her faith. I, too, have chosen to believe. In the process, I have discovered that belief has led to seeing and knowing.

We often say that “seeing is believing.” In the spiritual realm, however, the reverse can also be true: often “believing is seeing” or “knowing.” “Seeing is believing” captures how we know with our natural eyes and senses. “Believing is seeing” captures how we often know with our spiritual eyes.

Both ways of knowing are important. We naturally believe what we see and test truth claims against empirical evidence and reason. A dollop of healthy skepticism and doubt can serve as prologue to knowledge. As Descartes discovered, dubito (I doubt) can lead to cogito (I know).

In the spiritual realm, however, it is also true that “credo” (I believe) can lead to “intelligo” (I understand). I am fond of a Latin saying, “Credo ut intelligam.” To parse the Latin, this means “credo” (I believe); “ut” (in order); “intelligam” (to know). “I believe in order to know.” Credo ut intelligam.

This saying contains an important spiritual truth: believing can enable us to see and know. Belief can give us eyes to see and ears to hear.

John Tanner, left, with President Gordon B. Hinckley, right.

John Tanner, left, with President Gordon B. Hinckley, right.

As I have nurtured the desire to believe, I have discovered that, paradoxically, believing becomes seeing. My testimony has opened up vistas unavailable to a skeptical world and has influenced how I see everything else. As C. S. Lewis says, “I believe in Christianity as I believe that the Sun has risen, not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”[4]

I have discovered that the gospel puts all truth into proper perspective. It casts light on, well, everything. It helps us see “things as they really are, and . . . as they really will be” (Jacob 4:13).

So how has believing helped me see things as they really are? And what does believing help me see? Here are a few very quick examples:

Belief in the Creation enables me to look at the sun, moon, and stars and see “God moving in his majesty and power” (see Doctrine and Covenants 88:45–47) rather than as the meaningless motion of mere matter, spinning silently in the void.

Belief in the Atonement enables me to see glorious possibilities in my children, neighbors, and even myself—to catch glimpses of gods and goddesses beyond the small, weak, petty, stumbling, backsliding creatures we sometimes seem to be.

Belief in the Restoration enables me to read history and the daily news with a sense of where the human pageant is heading, despite the horrors and the headlines, and have confidence that God is working out his designs despite human folly and failings. Ultimately good will prevail and “all shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.”[5]

Belief in the Resurrection allows me to “love that well which [I] must lose ere long,”[6] knowing that the same sweet “sociality which exists among us here will exist among us there” in eternity, “only coupled with eternal glory” (Doctrine and Covenants 130:2).

Belief in God’s providence often opens my eyes to discern the minor miracles that heaven pours out on us daily if we but have eyes to see them—though I don’t discern the hand of providence quite as often as does my beloved wife, Susan, for whom seeing life’s little daily miracles is a spiritual gift.

In short, believing has helped me see and know things of the Spirit, no less than seeing has helped me know and see things of world. I am grateful for both ways of knowing.

Conclusion: Tasting as Knowing

I have spoken a lot about seeing as a way of knowing, literally and spiritually. In conclusion, let me touch briefly on tasting and knowing.

Linguistically and spiritually, tasting is deeply associated with knowing. In every Romance language, there is a verb for “to know” that ultimately goes back to the Latin for “to taste.”

Saber in Spanish and Portuguese and savoir in French derive from sapere, the Latin for “to taste.” These verbs for knowing denote a particularly emphatic claim to know. They speak to a kind of knowing that contrasts in each language with merely being acquainted with something: “conocer” “conhecer” and “connaître.” When people say lo sé, eu sei, or je sais, they are saying in a derivative, distant, but distinct way, “I know in the same sure way as I know something I have tasted.”

I know—and you also know—things of the Spirit from having tasted them. We know the gospel is true because it is sweet, delicious, and fills us with joy and delight. We know because we have tasted. Consider these phrases from Alma 32.

“It beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me” (verse 28). Note that from the very first of the extended simile, Alma refers to knowing by tasting. He says that the seed begins to be delicious while it is still germinating, before it produces fruit. As the seed begins to swell in the breast, it enlarges the soul and enlightens the mind. This sensation is both real and delicious. Thus, the seed yields the fruit of knowledge by tasting good even while it is yet a seed.

“After ye have tasted this light” (verse 35). Similarly, we read a bit later of tasting light as the word begins to expand and enlighten our understanding. Some might see this as merely a mixed metaphor. Fair enough, although aren’t all metaphors mixed? I see it as a striking instance of spiritual synesthesia! The light is real and good and discernible, like the light the hand “sees” in the painting I See You, God. This experience with light is so marvelous that we can almost taste it!

“Ye shall pluck the fruit [of the tree] . . . , which is sweet above all that is sweet” (verse 42). Not until the end of the chapter does the seed become edible fruit. Up to this point, the word has been a swelling seed and then a tree taking root—both of which, by the way, are described as growing inside us, as spiritual knowledge does. The evidence provided by the experiment has been internal. It comes from things that are felt and tasted more than seen. But the culminating experience of knowing in Alma 32 comes from tasting a fruit that can be both handled (“pluck”) and seen (“white”)—and, above all, tasted! And what an experience it is to know by eating a fruit that is delicious to the palette (it is “sweet above all that is sweet”), delightful to the eye (“white above all that is white”), and deeply satisfying to our deepest hungers and thirst (“ye shall feast upon this fruit even until ye are filled, that ye hunger not, neither shall ye thirst”; verse 42). Clearly, it’s worth the work and the wait to feast on such delicious fruit. Tasting it is the culminating experience of knowing in Alma 32.

Yet this fullness of knowledge comes only at the end of a long season of planting and nurturing. So it is often for us: sometimes we don’t taste the fruit of the gospel and know until we have cultivated the garden of faith for some time. But then we do know, and know with certainty, because we taste the fruit and it fills our souls with joy.

Nowadays, people are often hesitant to say “I know” when it comes to things of the Spirit. I understand this reluctance and do not in the least minimize the importance of believing. To say “I believe” is to make a very strong claim in our skeptical and secular world. But most members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints can legitimately say even more. They can say “I know.” As do I!

Let me conclude my remarks on the reason for the hope that is in me with this verse from Alma 36: “For because of the word which he has imparted unto me, behold, many have been born of God, and have tasted as I have tasted, and have seen eye to eye as I have seen; therefore they do know of these things of which I have spoken, as I do know; and the knowledge which I have is of God” (Alma 36:26; emphasis added).

Taste. See. Know. I have not seen open visions like the Prophet Joseph. I have not seen an angel like Alma. But I have tasted. I have seen. I do know.

Notes

[1] See Blaise Pascal, Pensées de M. Pascal sur la religion, et sur quelques autres sujets (Garden City, NY: Dolphin Books, 1846), section 4, no. 277.

[2] Izaak Walton, The Lives of John Donne and George Herbert, vol. 15 of the Harvard Classics, ed. Charles W. Eliot (New York: P. F. Collier, 1909), paragraph 89.

[3] Last Notebook (1880–81), Literaturnoe nasledstvo, 83:696, as quoted in Kenneth Lantz, The Dostoevsky Encyclopedia (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 2004), 21.

[4] C. S. Lewis, “Is Theology Poetry,” in The Weight of Glory: And Other Essays (New York: HarperCollins, 1949), 92.

[5] Lady Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love, ed. Grace Warrack (London: Mehuen and Company, 1901), chapter 27.

[6] William Shakespeare, Sonnet 73.