Schools

Douglas D. Alder, “Schools,” in Dixie Saints: Laborers in the Field, ed. Douglas D. Alder (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 49-94.

Introduction

When Mormon villages were founded in the period between 1850 and 1900, their leaders were urged by the Church headquarters in Salt Lake City to establish a school in each village. In most towns, they implemented a plan to survey the town into blocks with about eight one-acre lots in each. In the center of the town, they devoted the central block to serve as a town square. Initially, they often built a bowery there for Church and town meetings. Then they divided the other blocks into family plots. Irrigation ditches were dug down each side of the wide streets so that the families had water for their gardens. Each of the families received one of the one-acre lots and began to set up a chicken coop, a pigpen, a root cellar, and a corral. They lived in their wagon or in a tent at first, but as soon as possible they built a cabin.

Civic buildings were just as essential. Within a year people usually built a modest church and a school, often on the town square, to be a center for the one hundred to four hundred residents. Sometimes, both functions were housed in the same building. Each community elected a group of school trustees that was responsible to arrange for a place where the school classes would be taught; obtain furniture, books, and supplies; hire a teacher; and collect tuition. Because St. George was at least four times bigger than most villages, the town was divided into four wards, and each had a one-room school. There were also some women who taught school in their homes in St. George.

The majority of youth in the Dixie region attended their local school. In the 1860s these schools may have only offered three grades, but by 1900 schools were expanded to six grades, and soon eight. However, there were not eight classrooms. In some schools there was only one teacher, and all classes were in the same room. Another room was often added, allowing for two teachers and divided the grades into two groups: beginners and advanced. Three rooms and three teachers were rarities. Many students did not attend a full year because they had to be available for the planting season and the harvest work. Also, many students had to drop out before the eighth grade to help with work at home on a permanent basis because one of their parents was seriously ill or had died. It was not uncommon for young people to quit school by age fourteen.

Initially, each community had to finance the schools. They often received some LDS Church support but little supervision from the central Church; nonetheless, religion was usually taught in the schools. In succeeding decades, the local LDS leaders in the village sometimes arranged for a religion class to be taught by a member of the congregation once or twice a week as a supplement to the school curriculum.

As political leaders in Utah planned for statehood, the territorial legislature began to appropriate modest funds to the schools. At first, each county received one dollar per student, until it was later increased. Elementary schools—unopposed by the LDS Church—began a gradual process of secularization.

High schools were a different matter. Statehood was achieved in 1896, and the state and county governments gradually promoted the establishment of publicly supported high schools. In Washington County, there were only two: one in Hurricane and one in St. George. The latter began in the Woodward School when the county added grades nine and ten a few years after the 1901 opening of the school. Woodward School, located on the town square, had consolidated the four one-room schools into a two-story building where eight grades were taught, with a teacher for each grade. When the LDS Dixie Academy began in 1911, grades eleven and twelve were added, making a full high school. The Hurricane High School began about 1918.

The LDS Church leaders in Salt Lake had made a significant decision in 1888 to establish a network of academies. They had concerns that state-supported high schools would soon take over and eliminate the teaching of religion in the schools. They wanted access to the youth in the schools in order to teach them religion. These Church schools required students to pay tuition of ten dollars, whereas state-supported schools did not. The Church appropriated substantial amounts to support faculty salaries; they also generally paid half the cost of building a two-story, multiple-classroom school. These schools soon made grades nine to twelve available to students. The academy began in St. George in 1888, but only the grades up to the eighth grade were available, and it closed in 1893. Then, in 1911, it started again, making grades nine through twelve available as well. In 1916 Dixie added a year of teacher preparation courses, beginning the first year of college. In 1917 a second year of teacher preparation was added as teacher certification standards were raised statewide.

Several people have written about Washington County schools. In 1923 Josephine J. Miles read a paper on the schools to the St. George chapter of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers.[1] She focused largely on St. George, detailing the efforts of individual teachers clear up to 1900, prior to the creation of ward Church schools. She says: “Methods and equipment improved generally, and in about 1888 there was an appropriation from the state of fifty cents per student per term of twelve weeks. This gave a little cash to go along with our pickles, broom, wood, molasses, etc., for we had to collect our own pay from the parents, furnish our own wood, clock, brooms, etc. and hire our own janitors.”[2]

In 1961 Dixie College professor Andrew Karl Larson wrote I Was Called to Dixie. He devoted chapter 32 to the topic of schools. After focusing on the early community schools, he then dealt with the St. George Stake Academy (1888–93), the construction of the Woodward School (1901), and what became Dixie College (1911), which expanded in 1916 to include college courses for teacher preparation.

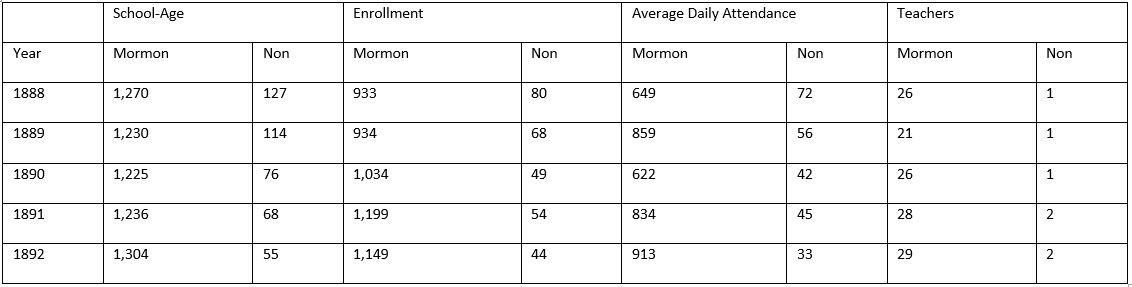

A major study is Robert Hafen Moss’s 1961 master’s thesis at BYU, which focuses on education in Washington County from 1852 to 1915. Moss cites Josephine Miles, Andrew Karl Larson, and Albert E. Miller (all three are historical scholars of Dixie), but he includes much more detail. For example, he includes a chart about the school population between 1888 and 1892 that shows the Silver Reef Mine brought in a considerable non-Mormon population. It is clear that the student enrollment declined as the mine began to close. The accompanying chart also shows that about one-fourth of the youth in the whole county did not register for school and another one-fourth of the youth did not attend regularly. Moss observed, “This substantial segment of the total population was not educated in the district schools, thus presenting an argument in favor of free public schools.” [3]

Enrollment Chart

A letter from the county school superintendent, John T. Woodbury, to the St. George stake president, John D. T. McAllister, expressed the schools’ financial difficulties:

The amount of school money allotted to Washington County for the year 1888 is $2794.00. This is apportioned to the various districts. The above money can only be used for the payment of qualified teachers. In St. George during the past winter, the pupils in the ward schools received the benefit of one dollar of this money for every term they attended school. The amount was deducted from the tuition fees of each pupil, and the bill sent to the parents only for the remainder. The short time that the schools are kept up here during the year, and the small wages paid to teachers, make it necessary that they should spend their spare time in other kinds of employment, and [if] they cannot give attention they should do to the cultivation of their own minds and improvement in the art of teaching. The trustees have power to levy a tax of one fourth of one per cent on all taxable property in the district for the purpose of supplying the school with fuel, maps, charts, etc. But in most cases this tax is not levied, and the school runs on without these necessary aids to successful teaching.[4]

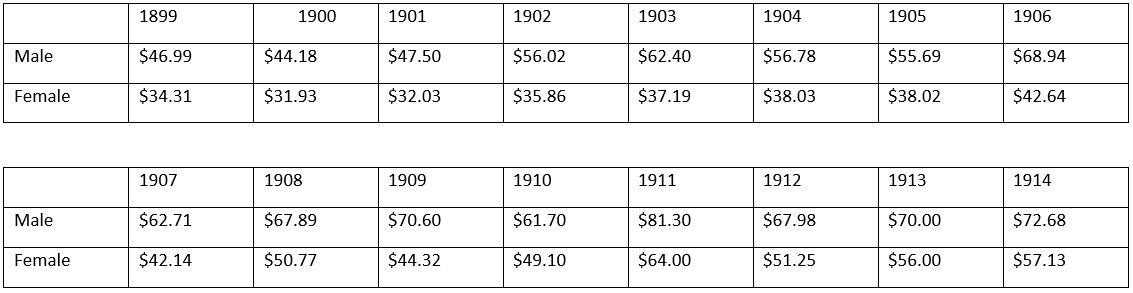

This chart is a glimpse at the financial challenges facing the schools and gives a view of teachers’ salaries:

Teacher's Salaries

Moss’s concluding findings in his thesis were the following:

From the beginning, the major force present in the establishment and support of schools in Washington County was the LDS Church. Local church leaders were very often the educational leaders, . . .

The power of administering the schools rested largely on lay personnel from each community elected as district trustees. . . .

Financing of the schools was largely a local affair during the first fifty years after settlement. . . .

Many difficulties were encountered in establishing secondary schools in Washington County. Paramount among these was finance. . . .

The greatest achievement made during these seventy-five years was the consolidation of Washington County Schools.[5]

What is amazing is how the teaching of students began with zest in every village, even if the only meeting place was in a tent. All villages implemented the Mormon model of a local school with local trustees. Obviously, educating children was one of the main purposes of the village. People came forth to be teachers despite the severe limitations of living in the desert and the lack of money to pay them appropriate salaries. Families sent their children to schools but often had to limit their attendance so they could help farm, ranch, nurse the ill, cook, or clean. They rallied to build schools and pay tuition long before Utah became a state in 1896. By the time that free education was available to all, almost everyone was literate. Education was valued, and gradually a tax system was put in place to support it. Most of these struggles preceded the years of schooling these interviewees experienced. But even with improvements, students still attended only when they could be away from the farm or home, where work dominated life.

A personal but enticing account of education in St. George was written by Andrew Karl Larson.[6] It captures his struggles to get an education, but many other students had similar experiences. Larson lived and finished school in Middleton; he reports that school was held in the town church with two teachers: one teaching the first four grades in the basement and the other teaching the four upper grades on the main floor. He recalls scenes of teacher discipline and of his interaction with other students. He was very fond of his teachers and tells many tales about them. One of the teachers, Mr. McConnell, motivated Larson to join the band, which introduced him to Wilford McAllister, who led him further into music, especially public performances. Another teacher, Willard Nisson, carried that tradition of student activity on in the upper classes. Larson then began participating in debates. He engaged in one debate in costume. That led him into a lasting friendship with Leonard Sproul, a man who later became a community leader.

Larson also tells of learning how to do other things outside of school—peddling grain, meat, and vegetables with his “pa” on a trip to Parowan and weaving rugs with old cloth strips. He enjoyed amusements and holidays: Christmas as well as Pioneer Day, with its horse races and broad jumps. He tells about a storytelling contest at Mutual Improvement Association. The two other contestants were smart girls from his class. He chose a short story from the Juvenile Instructor, and the girls chose classics. He practiced his story aloud many times at home and later recounts: “There on the Sandy Knoll I told and retold the story, narrating it with a feeling I really lived. I liked the way it sounded, and I learned where to place the emphasis, the pauses, and the speedup by some sort of instinct for an effective style of delivery. I tried not to overdo it.”[7] The meetinghouse was packed for the contest. He was the first speaker, and then the two girls gave their stories, but he felt that he had won. The judges did indeed pick him, and he won the one-dollar prize.

That experience stirred him to become a reader. He read Parley P. Pratt but then moved on to authors like Charles Dickens and Hans Christian Andersen; he also read The Last of the Mohicans, “The Song of Hiawatha,” and even the Gettysburg Address. His parents could see that learning was his forte, and despite their need for his help on the farm, they planned to send him to Dixie College, which was founded when he completed eighth grade. But they had no cash; when he finished the last year of town school, they were unable to find the ten dollars necessary for tuition nor figure out how to arrange living quarters for him in St. George. They encouraged him to repeat the eighth grade. He started but became discouraged and dropped out. The next fall, the same issue arose. They did not have cash. Then, Hugh Woodward, principal of the high school that became Dixie College in 1916, came to their house and urged the parents to sign a loan application for the ten dollars. Woodward was recruiting two other Washington City boys and suggested that they ride horses to and from school each day and avoid the cost of housing. He said that if the father could come up with five dollars, the plan could work. On that basis, Larson started at Dixie, a decision that would eventually lead him to a lifelong profession of teaching college.

Four years after the founding of the high school in 1911, Larson became a serious student there. He fell in love with literature, particularly the British authors William Shakespeare, Sir Walter Scott, and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, as taught by his teacher, Mill Ruth Carol Evans. The horse rides to school every day were difficult, especially in the winter. He sometimes felt like the English knights he read about, trying to conquer the forests and hills.

Debate also became exciting for Larson. He tells of a contest he participated in, where he and another boy, Tennyson Atkin, debated against two girls on the subject of women’s suffrage. The boys took the negative side of the issue, which was tough because Utah already had women voting. The boys won the votes of all three judges, mainly because of fellow student Tennyson Atkin’s knowledge on the subject. One of the judges was Nels Anderson, the school’s debate manager.

Larson’s ability to perform in the band led to playing college musicals that were presented in the opera house and sometimes in Hurricane. This meant that his horse ride home after the performances didn’t conclude until midnight. He even played in the marching band to celebrate Armistice Day in 1918.

He alternated months going to Dixie College and months at short-term jobs whenever he could find them, trying to finance his schooling. Sometimes he went to Idaho, then to Delta, and often to Washington City. He always felt he should be in school. One fall, he and six others (young men and young women) rented a basement north on Main Street with an outdoor cranny (outdoor toilet). That year Andrew had two serious bouts of illness, one with typhoid fever and another with inflammatory rheumatism. With the help of Dr. Donald McGregor and a blessing from his father and mother, he returned to school. He was way behind in his classes, but his teachers helped him catch up.

During this time, he struck up a friendship with Katherine Miles. They did not date because he could not afford to take her out, but it eventually led to marriage. He tells of the dedication of Zion National Park on 15 September 1920. The Dixie Band, under direction of Earl J. Bleak with Larson participating, was front stage. Stephen Mather, national parks director, presided. President Heber J. Grant, Senator Reed Smoot, Richard R. Lyman, Governor Simon Bamberger, Anthony W. Ivins, Edward H. Snow, Thomas Cottam, and George Whitehead were on the stand also. Cameramen from Paramount Motion Pictures roamed about.

Andrew even tells about a student court and an appeal to President Joseph K. Nichols. The issue was a hazing incident involving the son of Archie Wallis, the editor of the Washington County News, and a group of students including Larson. It was tense but came to a resolution. This is but one example of the importance of student government at Dixie as instituted by President Hugh Woodward upon the founding of the college.

As a senior at Dixie, he played in the band directed by Earl J. Bleak but also attended John T. Woodbury’s Bible class. He did his practice teaching at Woodward School under Lena Nelson, who later became his colleague there. Andrew Karl Larson’s book is a classic, well-written illustration of the impact of education in Utah’s Dixie.

A different view is to compare the schools in Utah’s Dixie with those in Salt Lake City. A major educational scholar in Utah was Frederick Stewart Buchanan, who died January 2016 in Salt Lake City. He was born in Scotland, where he joined the LDS Church and came to Utah. He became a professor of education at the University of Utah. His book Culture Clash and Accommodation: Public Schooling in Salt Lake City, 1890–1994[8] gives a picture of Utah public education that was nearly the opposite to what happened in schools in southern Utah, northern Arizona, and Nevada villages that neighbored Utah.

The schools in Buchanan’s book were all tax-supported and administered by county and state school boards, in contrast to southern Utah. Buchanan’s main point is that Salt Lake City was internally diverse. After the railroad arrived in 1869, more and more non-Mormons settled there, becoming over 20 percent of the population. The mining industry became successful. As the prosecution of polygamists expanded, non-Mormons actually gained the office of Salt Lake mayor. Catholic and Protestant churches and fraternal societies grew. By the time of statehood, both elementary and secondary schools were state-supported, becoming tuition-free. In 1891 there were 209 non-Mormon teachers and 700 Mormon teachers in Salt Lake County.

Buchanan’s work is worth mentioning because it is a contrast and brings perspective to the History of Woodward School, 99 Years, 1901–2000 by Heber Jones.[9] Jones tells of the decision promoted by a lobby group led by Miss Zaidee Walker, which pressed for a professional school building to serve St. George City. She had studied at the University of Utah and seen such buildings in the capital city. The lobbying finally convinced the St. George School Board to bond for fifteen thousand dollars and build a two-story, eight-grade, eight-teacher school. They even stayed with the task when the costs escalated to thirty thousand dollars. When opened in 1901, the Woodward School replaced four ward schools in St. George. The Woodward began with eight grades and soon added grades nine and ten. When the St. George Stake Academy opened in 1911, it was a high school, teaching grades eleven and twelve. Then, in 1916 and 1917, two years of college (teacher preparation) were added to the academy, which by then was named Dixie College. The college then included the last two years of high school and the first two years of college and remained that way until 1963, when the college moved to the new campus on Seventh East. Grades eleven and twelve remained in the old college building on the town square, under the direction of the county school board.

Another article that should be mentioned is by James Allen, titled “Everyday Life in Utah’s Elementary Schools, 1847–1870.”[10] He pointed out that even though schools were opened in every Mormon village, not all families could afford the tuition to send their children to the schools. Tuition was ten dollars a year. Allen says that only about 50 percent of youth attended. Also, he noted that books were generally unavailable in the very early years. Of those who attended, some dropped out. Then, he noted that by 1900 the state legislature made public funds available for elementary schools. Tuition was no longer charged, and they instituted requirements for attendance.

Interviews

Some twenty-nine students are quoted in this chapter. Not all of them went to school in the Dixie region, but most began school in a village. A few went to high school by leaving their village. Even a smaller number went beyond that. They usually remembered teachers, friends, and pranks fondly.

There were many reasons for terminating their education early—health, family emergencies, employment, and marriage. The most interesting way to understand this is to read their words. Here are a few of them.

Wilford Woodruff Cannon

Wilford Woodruff Cannon was born on 20 November 1880 to David Henry Cannon and Rhoda Ann Knell Cannon. His father was a counselor in the St. George Temple presidency and later became the president. Wilford tells: “When I was born, President Wilford Woodruff was president of the St. George Temple. My father was his assistant. Father carried me down to the temple where President Wilford Woodruff was hiding in the temple because of polygamy. He took me in his arms and gave me his name and a blessing when I was eight days old. That is [recorded] in father’s diary.

“I grew up in St. George and, like other [children], I attended [the] district school. In the good old days, once a month the teacher would [hand out] a little bill [for the students to take] home to [their] parents and they would pay the bill. I was in second or third grade before they introduced [the] public school [system]. There were little one-room schoolhouses all around town. Until I was [in the] fifth or sixth grade, I attended these one-room houses. After maybe the sixth grade, we had a central school up in the top floor of the courthouse. I went there a couple of years. Then we met in the basement of the [St. George] Tabernacle from then until I finished the eighth grade.

“In 1899, I went to Cedar City [Iron County, Utah] to attend the Branch Normal School. When we went up there, we had to take ‘Old Dobbin’ and the shay. It took us three days to get to Cedar City [from St. George]. We took a team, [and] two of my sisters and I went up and rented an apartment in Cedar City. We took a lot of our provisions from here with us. While I had that team up there I went to the canyon and brought down a load of coal. I went out into the sticks and [picked up] some wood. My two sisters and I kept warm that way.

“The next winter the three of us went up to BYU in Provo. We went around through Modena [Iron County, Utah]. We took a train from Modena and went to Provo. We rented an apartment there and attended school that winter. George [Henry] Brimhall was the head of BYU that year. I enjoyed BYU quite a little. I wanted to study engineering, so the next winter I went up to the University of Utah. They had just moved out on the hill (where they are now) the [previous] fall. They only had three buildings at the university then. I stayed there four years [and studied] mining engineering. As soon as school was out, I left and went out in the sticks to do [work in the] mines.”[11] Such is the report of a young man from the capital town of Dixie supported by one of the most privileged families.

Verda Bowler Peterson

In contrast, consider Verda Bowler Peterson, who was born in Hebron on 21 November 1904: “We moved from Hebron to Enterprise when I was about a year old [not long before the earthquake put an end to the town]. There isn’t anything there except for one or two old trees.

“My first teacher was Dora Woodbury. I had her for a couple of years. My next teacher was Fanny Klyman from Toquerville [Washington County, Utah]. Althea Gregerson was the next one. I had Willard Canfield and Bernie Farnsworth. I liked all my teachers. By the time I went to Bernie ([he] was more outstanding in my mind), I was possibly in the sixth or seventh [grade]. They used to have contests [at] school in writing the times tables. I won the blue ribbon [once]. I remember losing it one night. I remember getting up the next morning as soon as I could see. I knew where I had been the night before. I went to see if I could find my blue ribbon, which I did. I was tickled to death to [find] it because it meant [a lot] to me. I liked school a lot.

“I remember [the] girls used to play marbles with the boys on the sunny side of the school building. I didn’t win very often. I think [the boys] cheated.

“[My] next teacher [was] Will Staheli. He was an outstanding teacher. He had a way of bringing out of you what he wanted to. In our history class there [were] two or three of us that had the history book that had the last chapter or two in it at the end of the year. I happened to be one of them. He was going to have us give the last [lesson] of the course. History was hard for me, so I [was] prepared and asked him if I could have my turn first in class that morning. He said yes. I memorized it, and I went through it. I about covered the whole thing. I didn’t have to use the book. He was a good teacher. He couldn’t sing, but he could sure put music over. He could make the people understand what he was trying to do. He wasn’t a very good singer, but he was really good in music.

“I didn’t go on to high school because, at the time, my mother had poor health and we had a large family. It was a family of twelve, and we didn’t have a lot of money. They didn’t hire people then like they do now. There weren’t people to be hired or money to pay them. So [the] girls had to stay out of school. My older sister was not too well. I stayed out [of school] a lot. Before that, I wouldn’t miss school for anything. After I had to stay out a lot, I began to look for excuses to stay out [of school]. I got discouraged and I never did go further than the eighth grade, about age fourteen.”[12]

Leslie “Les” Stratton

Leslie “Les” Stratton was born in Hurricane on 11 November 1908. He tells of the demands of farming on a male student: “I got every bit [of schooling] I could. We usually had to work in the spring to get our crops in and we usually had to put the crops up in the fall. I did not always get a full year of schooling. When I [was old] enough to be in high school, the last four years of high school, I did not get any credit for them because I did not complete them all. I kept right on through, one year after the other and [had] all four years in, but there was no credit for the full year because I was out in the spring and the fall, for about three months of the year.

“We used to have nine-month schools, and I [went] about six months a year. I was good enough to make the basketball team. Bishop Church from La Verkin was the coach. We beat every team but St. George. We had a dandy team. I played baseball and was chosen by the county down here to represent Washington County in baseball and played at the [Utah] State Fair. I played first base. I think I was the biggest shot there because the first two balls that were knocked came straight to me.”[13]

Theresa Cannon Huntsman

Theresa Cannon Huntsman was born in St. George on 20 October 1885. She attended school in St. George, Cedar City, and the University of Utah before Dixie College existed: “I did not start to school as soon as I was six years old. The school was quite a ways from my home. I was small, and Momma thought it would better to wait until the next year, so I got a late start [in school]. I loved school and wanted to go. After I started, I really loved school, and I never wanted to stay out; it made me sick to be sick.

“There were schools in small houses all over town, one in every four or five blocks. We had some very good teachers in St. George. Our first teacher was Mrs. Mary Judd, and she was possibly in her thirties. She was a married woman, and she was a good teacher. The next teacher I went to was Rose Jarvis, another good teacher that I loved very much. Then Martha Snow Keats was the next teacher. In 1901 the Woodward School started. Before that, we went to [class in the basement of the St. George] Tabernacle and to the [Washington County] courthouse for one grade. In the basement of the tabernacle we had several grades that year. John T. Woodbury was my teacher after I reached the seventh grade.

“They would make a class for us [even when a class was not available]. In that way I took several of the grades over. When it came to eighth grade, I took that over two years. The first year I was ill and had to quit, so I took it all over the next year. I did that with two of [my] high school years because I wasn’t well, and my heart was bad. Then I went to Cedar [City] for a while, and I went to the University of Utah for a while, but I never did complete the college courses.”[14]

Dora Malinda Clove

Dora Malinda Holt Clove was born on 2 April 1894 on Holt’s Ranch near present-day Enterprise. She began school at Hebron. In her interview she said: “[During] our early [education] we would go maybe five months of the year and that [would be] the end of our school [year]. We would [have] the same amount of [school days] every year and have to start over the next year. The first part of [the school year] we got done well. We had grades. We were all taught in the same room, [with] several grades in one room. We really liked it. My brother taught [in] my first [school]. [His name was] George O. Holt.

“We would have so many minutes for each class. We had arithmetic, grammar (as they used to call it), reading, writing, [and] spelling. We had part [of our studies] in the forenoon and part in the afternoon. I wasn’t the best reader in the class, but I was right next to it! I was a good speller, but I wasn’t too good in arithmetic. I could do it until we got up to algebra, [but] I didn’t do too badly.

“When we came down here to Enterprise, I was seven years old. We went up to eighth grade. I went to [school in] Cedar City [for] one year. I really liked it, but I didn’t stay and finish up. When spring came, my father had to be out on the farm, so he called me to come back and take care of the store. He had a general merchandise store in Enterprise. I worked there until I was married and [for] a little while afterwards. My husband wouldn’t let me work anymore. He said he didn’t get me to work in the store, he [married] me to be a housewife.”[15]

Alvin Hall

Alvin Hall was born on 17 October 1890 in Rockville and attended school there through seventh grade. He then went to the eighth grade in Hurricane. Following that he went to high school in St. George and continued his education at Utah State Agricultural College in Logan. He said in his interview: “[I started school] in Rockville. They had two teachers, a man teacher and a lady teacher. They had two buildings. My first teacher [was] Loretta Stout. They had the lower grades in a different building from the higher grades. I felt it was a detriment to have more than one grade together like that. When we went to high school in St. George, those [students] were familiar with a lot of things that we had never heard of [before]. They had taken a lot more classes than we had [available in Rockville].

“We had mostly good teachers [in Rockville]. [Some of those teachers were] David Hirschi, George Cole, Loretta Stout, [and] Jenny De Mille; [her name was] Jenny Petty at the time. I went to the eighth grade after we moved to Hurricane. I graduated from the eighth grade here. I was out [of school] several years [after that]. My dad did not want me to go to high school; he needed us on the farm. He said it was all foolishness. I waited until I was twenty-one years old, and I went to high school in St. George anyway. I went to college ten years later when I had a wife and five [children]. My younger brother [Henry Vernon] had a job in Logan running the experimental farm for the college. He gave me a job on the experimental farm. I moved [my] family and went up there. I went to school part-time and worked on the farm on Saturdays and after school. I took two winter courses there. I [took] some college [classes] while I was in St. George [too]. [I have the equivalent of] about two years.”[16]

Victoria Sigridur Tobiason Winsor

Victoria Sigridur Tobiason Winsor was born in 1891 in Reykjavik, Iceland. She came to America as a child and lived in Logandale, Nevada. In 1901 she was baptized in St. George. She started school in Hebron, where she lived with the Alger family. She reports: “I started school with their children. They had a girl [who] was in the second grade. [She was] just younger than me. She and I were learning to read words on the blackboard. They claimed that I was in the first grade, but I don’t know; I didn’t know the difference. They taught me words with some of the other children. It was only a little while until they put me in the same class with her, and she was in the second grade. I was only a month or so in school.

“When I came down here to live with Aunt Effie and Uncle Frank [Winsor], I was in the second grade. [I had] a special tutor up there [because] they had a small school. Children learn faster in a smaller school, believe it or not. It was only a little while [before] I could read as well as their little girl in the second grade. I could read in the book. I never was a good reader, but I enjoyed being able to read as good as she did. When I came down here to Aunt Effie and Uncle Frank’s to live in St. George, they started me in school about a week after I came down. They wanted to get acquainted with me first. I was started in the second grade. I was in the second grade a little while, and they put me in the third grade. I took the first three grades the first year. I still wasn’t up with my age, and I wanted to be with my age. During the latter part of the year, they didn’t promote me out of the third grade because I had already taken [skipped] two grades. When I started the next fall, they promoted me to the fourth grade. I was only there a little while. A. B. Christensen was the principal. He took me to the blackboard and had me do some number work. He was the one that taught me long division. He had the teachers put me in the fourth grade. At the end of the year, I was promoted to the fifth grade. Then I was up with my age, [and] I was more satisfied.

“I didn’t have much to do other than to study. I studied at home. Frank was good to help me read. I didn’t want to play with the other children because they laughed at me. I didn’t say my words right, and they kept asking me silly questions. They asked me where my grandpa [John M.] Lytle lived, and I said, ‘In Diamond Valley.’ They would ask my name and would say ‘Wictoria.’ They laughed! I wouldn’t play with the other children, and that gave me more time to study.

“I was twelve years old, I guess, when I ran a nail in my foot. I was playing hopscotch with the other children. Somebody left a board with a nail in it and I ran the nail clear through my foot between my toes. The teacher wanted me to go home, but I didn’t want to go home right then; I wanted to wait until school was out. I had to walk home anyway, and I didn’t want to go home without the other children. This was at recess, [and] I walked home after school. I put my arm around my brother’s neck and a neighbor boy’s neck, and they helped me walk home. By that time, it was quite sore. I was out of school for six weeks with that. It got [an] infection, and I nearly had lockjaw. They promoted me just the same, [and] I didn’t miss my grade. They sent books home and told me to study my lessons at home. When I was fourteen years old, I moved to Enterprise and I finished my grade school [education] up there. I was the first student in Enterprise to graduate from the eighth grade.

“I didn’t go to school for a few years. I was quite sick when I was in my teens. I wasn’t very strong, and I got kind of thin. It was cold out there, and I had rheumatism bad. I had rheumatic fever, and that kept me from going [to school]. When I [was] better, I went to [school] in St. George. They gave you credits in units then. I took five units the first year. The next spring I was called to take [over] kindergarten, especially in the Sunday School class.”[17]

Isabelle Leavitt Jones

Isabelle Leavitt Jones was born on 26 November 1904. She reports: “I was living [in] Gunlock. I should have started [a] year [earlier], but we were living in Las Vegas at the time [because] my father was working there. Las Vegas was just a village at that time. My mother had a bad case of pneumonia that winter, so I didn’t start until I was about seven. I can remember the house [where] we lived [in Las Vegas], and there was sand everywhere. There were a few buildings going up that were quite nice sized. My father worked with his team.

“[The school in Gunlock was] a one-room schoolhouse on the hill. The younger children sat on a board that was placed [across] five-gallon cans. That was where we sat the first year [in what] was the beginner grade. They had nine grades in [the] district school at that time. George [Hebron] Bowler was the teacher [and] his wife, [Nancy Elizabeth Holt Bowler], came and helped with the younger ones [when] he was busy. He was a good teacher. He moved to Mesquite the next year.

“They called it beginners [not kindergarten]. [Children] did not go [to school] until after they were six; in fact, I was about seven. I really liked school. All our activities were [held] either in school or church. It seemed like we worked hard [and] I had a lot of [chores to do] around home. I started washing dishes before I could reach the table to wash them without [using] a stool. [This was a] necessity [because] my mother had such a big family.

“We moved in October of 1910. I was almost nine years old. [The school] was in Mesquite and was a contrast to the little one-room schoolhouse in Gunlock. They had three nice large rooms, three teachers, plenty of books and facilities, whereas in Gunlock [we] were so limited. I feel like it was a real opportunity for us to have lived there those six school years that we stayed there. [Education] was much better. Nevada had the money to pay their teachers. I think the teachers were of the same caliber, but teachers [who] have nine grades can’t give as much attention [as] if they have only three [grades].

“When we left Mesquite, we moved to Gunlock and then to Veyo. It was known as Glen Cove at that time [and] hadn’t received the name of Veyo. It was just a pioneer village and only a few families lived there. They boarded up a big tent and put a stove in the middle of it. We gathered up a few benches here and there, and that was my eighth grade. It was in a big boarded-up tent, and we held our church services there too.”[18]

Lemuel Glen Leavitt

Lemuel Glen Leavitt (born on 23 January 1905) and his wife, Florence McArthur Leavitt (born on 1 August 1910), are an interesting comparison. Lemuel’s young life was spent in Gunlock. He describes his school life: “I went to school right over here on the corner of this forty [acres] in a tent for about three years. Then a new schoolhouse was built down here. We had a wood stove and kept plenty of wood in it. We were dressed warmly, [and] I don’t think we suffered [from] cold then. Emma Abbott was my schoolteacher. George Bowler was the next schoolteacher. After we moved up to Veyo, we had James Cottam for a teacher for a number of years here. He is about the last [teacher] I can remember. No, there were [two] lady teachers here, Charity Leavitt and Lavonne Davis, before we went to St. George to school.

“I went to the sixth grade [in St. George], and then I didn’t go any more until the first year of high school. I went back another part of a winter after I graduated and didn’t go to high school. So I went part of the winter to the eighth grade again. I did some [classes that] I [hadn’t] in St. George. I never did graduate from high school. We [became] involved in other things, and I didn’t go on to school, much to my regret. My dad needed me. He didn’t want me to come home, but anyway I did and it was an easy way out, I guess. [That] is the only thing I can figure. [It was] just an easy way out of school.”[19]

Florence McArthur Leavitt

Florence McArthur Leavitt was the granddaughter of famous Dixie pioneers. Her maternal grandfather was Thomas P. Cottam, who supervised the construction of the main building of Dixie College from 1909 to 1911, and was in the stake presidency. Her paternal grandfather was Daniel D. McArthur, the famous Dixie pioneer. She did all her schooling in St. George. She said, “There was only one grade in each room. It was in the old Woodward School that is now the Woodward Junior High School, the old red-block building. My first grade was in the southeast corner on the ground floor. Edna Wadsworth was my first-grade teacher. My second-grade teacher was Mary Star. It was in the southeast corner and the other [class] was in the southwest corner of the building on the ground floor. The third-grade teacher was Anna (I cannot remember her last name right now). In the fifth grade I had Mrs. Seegmiller. She was a dandy teacher. She taught me and most of my children in the fifth grade. Harold Snow was my sixth-grade teacher. He was stake president for some time and also [the St. George] temple president later on. He was a wonderful man. I went [through] all eight grades there. My seventh grade teacher was Leland [Lee] Hafen, who was a prominent coach [at] Dixie High School and College, and also Vivian [Jacob] Frei, who was in the stake presidency and [was] a fine man.

“From the eighth grade I went over to the old Dixie College. The Dixie College and High School were combined. There I spent four years of high school and two years of college. At that time, [only] two years of college were necessary to teach. I had a teaching certificate that I [received] in the spring of 1930.

“I always liked school. I enjoyed my school. In those days, we had some programs come in, but we were more of an isolated school than we are today. We [had] to make our own fun and furnish a lot of our own programs. I think today the Dixie spirit in school is carried on, especially before the ball games. The year that the [basketball] team won and went back to Chicago was my graduating year from high school.[20] It was really filled with activity that winter. We had a lot of Dixie spirit! School was a lot of fun, and we tried to keep up with our [studies].”[21]

Elmer Rodney Gibson

A very different story is that of Elmer Rodney Gibson, born on 4 April 1895 in Duncan, Utah [near Virgin]. His father died as a very young man—only twenty years old. Elmer grew up in the home of his grandparents and his mother went back to live with her parents. He said that he really enjoyed his early life, working with calves and making lots of cheese with his grandmother up on the mountain. He started school in Virgin. He said that the school was a two-story rock building: “It had the tithing cellar under it. Yes, I remember when I [was] a little older, my stepdad [James Jepson Jr., who built the Hurricane Canal] was bishop, and they [collected] the tithing over there. They used to take tithing in-kind. [They would take] wheat, corn, beans, [or whatever people] had [to give for tithing]. That is where they stored it. [It was] in [the] cellar under the schoolhouse. [It] was a big two-story rock schoolhouse. The [younger] children would go downstairs [to go to school]. Then, when we [were] about halfway through [school], maybe we would go upstairs. We thought we were getting pretty big when we got to go upstairs to [go] to school. There were two teachers. [There were] four grades for each teacher.

“I got along [fine]. I thought they were good teachers; they did their best; they seemed to be interested in the students. As I think about it as I [am] older, they seemed like they were there for the children’s welfare.

“[At the time], I went [to school] part-time. I left school before I [was] through [all the grades]. My eyes were a limitation, but I did not miss school on that account. I think we had five months of school [each year]. You had to get your work done [each day] before [school]. Mary [Eleanor] Jepson [was one of my teachers]. [She was a] stepsister. She was a good teacher.”[22]

Joseph Hills Johnson Jr.

Joseph Hills Johnson Jr. grew up in Tropic [Kane County, Utah]. He said: “My first schooling was in Tropic. I started school after I was seven. I do remember my first schoolteacher. [She] was Maggie Davis. I got along quite well in school there with her. I remember some of my schoolteachers. The next year, after Maggie Davis taught, Sarah Ahlstrom was my teacher. They were all lovely teachers, very fine. I loved them very much. Years later, Sarah Ahlstrom came back and taught me when I was in the fourth or fifth grades. I had her two different years.

“I only [went] to the eighth grade. I finished the work [for] the eighth grade, but about two weeks before the examination that was given at the end of the school [year], I was called out of school and never did take the examination. I had to go to work. However, a few years later, after we had been in Tropic, I went to Murdock Academy [in Beaver, Beaver County, Utah] for about six weeks. I was there the latter part of October until about December 15.

“My parents were determined that I was going to get an education. That was when I was sixteen. I herded sheep that summer and earned enough money that I thought it would put me through school. Father took me to Beaver. They were building the Murdock Academy at that time. [1] and two companions went with him, and we all rode to Beaver on a load of lumber about eighty miles.

“The schooling was wonderful, but it didn’t last very long. I was late starting school. I didn’t [arrive] until about a month after school began because I was working. I couldn’t get away. But I did start, and I remember a few things about the school that I would like to recall.

“I was put into a class of twenty girls. There were two boys and twenty girls. It was the algebra class. The teacher said that these boys could understand and grasp the algebra much faster than the girls. So he put them in a class by themselves, just two or three girls with them. But there were about twenty girls in the class. Wallace Henderson and I were put in the class with the girls, the second class or lower class. Wallace stayed with it about a week, and he couldn’t take it and dropped out. I stayed with it a few more days. I had never had algebra before, and somehow, after two or three days, it came to me and I could understand it. It seemed so easy to me. So the teacher promoted me back up to the boys’ class.”[23]

Vera Hinton Eager

Vera Hinton Eager was born in 1899, and her family, including her three brothers and three sisters, went to school in the earliest days of Hurricane. She recalls: “The first time that we went to school, my uncle Irie Bradshaw moved down from Virgin. He built a house which is still standing in Hurricane. After the bowery days, we would have school in one big room of his home. We would have school and church [there]. We would all be in this one room, and they would teach us. Later, when they built the first public school and church, we would have eight grades in the one big room, and one on the stage. We would go to these schools and be enrolled like the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth—all of the grades were in this room and on the stage. We would have to study when it wasn’t our turn to be having class. We were supposed to concentrate, keep our minds on our work, study, and do the things we should do for school while the other grade was going on out to the side of us.

“I remember one teacher, Chauncey Sandburg, would get so aggravated with some of the children. He would say, ‘If you don’t be quiet, I will throw you out of the window bodily.’ We all thought that was the funniest expression we had ever heard. Another teacher, Morgan Edwards, would come right down [to] us, [put] his hands under our chair and make us look right up into his eyes. He would say, ‘Now, what are you doing this for? Now, you behave yourself.’ He would use such a tone of voice that we were just a little bit afraid of him. I had a lady teacher called Sister Miles, and we really did love her. She was such a sweet woman. I will always remember what a wonderful teacher she was.

“When I [started] the eighth grade, I went to Hinckley, Utah, to stay with my grandmother [Elizabeth Staheli] Walker, who lived there. I went to school at Millard High School [in] Millard, Millard County [Utah]. I had quite the experiences there. I had never been away from home before. My mother was one of those strict women who would never let us use powder, paint [makeup], or perfume. My uncle Avery [was] a bishop [and] lived up there. He would tease me [by] saying, ‘I don’t believe Vera has looked in the glass [mirror] in two or three years. She has never used powder or paint. What does she need a looking glass for?’ I always thought that was quite strange.

“One day, I found some wintergreen in my grandmother’s medicine cabinet. I thought that it was perfume. I thought it smelled so good [that] I put some on before I went to Sunday School. I got it on fairly strong, I guess. I didn’t know how to use perfume. All of the people around me would say, ‘Where is that wintergreen smell coming from?’ I thought: ‘I guess that must be me. It must be wintergreen that I put on.’ When I went home, I washed [it] off, and never did use perfume any more. No more wintergreen!

“They had girls’ and boys’ day at the high school. I remember one day the girls were supposed to be up on the stage. The boys would march up. As they marched., they would take the girl who was opposite with them and would march on down. This time, the one boy that everyone made fun of happened to be paired opposite of me. Nobody liked him. He was quite a kooky [fellow]. When he came up to me, he threw his arms around me and gave me a big kiss. Was I ever embarrassed! I wouldn’t go out with him anymore that day. I went home, and I wouldn’t go anywhere because he did that up on the stage where everybody could see us. It embarrassed me so much. Nobody liked him anyway, and I wouldn’t be seen with him anymore. That was the first year of ‘high,’ as it was called in those days. Now it is called the ninth grade. I came back and took some of the eighth grade [classes] over again. I learned on the piano how to play a few marches. There didn’t seem to be anyone else who could play a march on the piano, so I would play these marches as they would march in and out of school. That was about the end of my school days.”[24]

Fern McArthur Hafen

Fern McArthur Hafen was born in St. George on 7 October 1912. She told of an unusual situation: “I went through twelve years of schooling [and] graduated from Dixie High School [in St. George]. I started the first grade [because] they didn’t have kindergarten in those days. Mrs. McAllister was my first-grade teacher. She couldn’t hear. She lived in two upstairs rooms [at our house]. She was a [member of the] Seventh-day Adventist [Church]. She used to come home and tell mother that I didn’t take too much interest in school. I liked to watch the birds out the window. In the second grade, Marjorie Brown [was] my teacher. She later married my uncle, Clarence Cottam. I really liked her.

“She was a good teacher. She took an interest in school and really made it interesting. In the third grade I had [Elizabeth ‘Bessie’ McArthur] Gardner. She was my cousin. I really liked Bessie. In the fourth grade we started to do a little more writing. [The teacher] noticed [that] I would write across the paper from the right to the left, instead from the left to the right. [The teacher would] love to hold it up before a looking glass to read it. Josephine Savage was my teacher in the fourth grade. She would stand by my desk every time there was anything to write. I was left-handed, and every time I put the pencil in my left hand she would change it to the right and stay right there until I wrote [the lesson]. I think this kind of upset my equilibrium.

“In the fifth grade, I had to stay back because I slowed down. Mrs. Brink was my teacher in the first year of the fifth [grade]. The second year in the fifth grade, Mrs. [Mishie] Seegmiller was my teacher. In the sixth grade, I had Harold H. Snow. He was a real good teacher too. In the seventh grade, I had Vernon Worthen. In the eighth grade [my teacher was] Jed Fawcett. [All] through high school we had [different] teachers for every subject. I quite liked school. I received my diploma.”[25]

Mary Amanda DeFriez Williams

Mary Amanda DeFriez Williams was born on 1 April 1902 in St. George. She told what it was like to attend the larger schools. “I went [through the] eighth grade in St. George [in the Woodward School]. I was vice president of our eighth grade. I was the first one to graduate of the grandchildren, so Grandpa Sorenson bought my graduation dress. It was a white taffeta. I will never forget that beautiful dress. Even today, the junior high school graduation is a big event in St. George. [It has] carried through the years. My husband [Kumen Davies Williams] was a student teacher when I was in the seventh grade. [Coach] Guy Hafen was my teacher. I will never forget that he was a teacher. We have laughed about it a lot. He taught me when I was in the seventh grade. [Kumen] was going to [Dixie] College at that time, [but] I did not know him. There was A. K. [Arthur Knight] Hafen. [He was] an English teacher, [and] I thought a lot of [him as a teacher]. John T. Woodbury Jr. was another teacher that I admired; he was a history teacher. There was Mr. Barkdahl; I have forgotten his first name. He is gone now. He taught me in art. When he left here, he went to Provo to teach. He wanted me to go to Provo and live with him and his wife [and study] art. That was after Kumen and I started to go together.”[26]

Mary and her friends in St. George had the advantage of attending a school where each grade was in a separate room and had a separate teacher. There were about twenty or more students in each class. They had a band in the school, and the students marched into the building each morning with the band playing. Other students, like Irvin Bryner, enjoyed describing each teacher and especially how they disciplined students. Some, who were beginners, sent the misbehaving students to Miss Lena Nelson, who was an expert in discipline. For example, she had them stand on one foot and hold an eraser in the air with the opposite hand for a long time.

Clarence Jacob Albrecht

Clarence Jacob Albrecht grew up in Wayne County, a long way from the heart of Dixie. He became a teacher in Hanksville and a Church leader and a member of the Utah legislature in 1949. These memories are of a student who was not initially focused on such achievements: “Being that we lived two miles out of town, I was not allowed to go to school when I was six years old. They kept me home and I resented this very much. By the time I was seven, I was now a full year behind the other boys and girls of my age. I will never forget the first day I went to school to the first grade. I wore a pair of new Levi’s my grandfather had purchased for me and a pair of blood-red shoes. They were about two sizes too large, and the [children] my age then called me ‘Dummy Red Foot’ because I was in the first grade and they were in the second [grade]. It didn’t take me very long to catch up with them though. I had a very good teacher who took direct interest in me. I believe her name was Mabel Baker. By Christmastime, she promoted me into the second grade, with those [children] of my age. I went on from there. I [0] quite well in school with the exception of reading. I never was a very fast reader. It was after I had [gone] through elementary school that I learned to read a little better. I had a fascinating experience when I graduated from the eighth grade. We had to go down to Bicknell [Wayne County, Utah], which was fifteen miles away, to take our eighth grade examination. This was quite a day for me. My father made arrangements that I would go with a neighbor in his car. How rich I felt when my father gave me $3.00 to spend that day!

“I went on through high school from there. It was in my high school year that I probably learned to study. I will always be grateful to Joseph Hickman, who was my uncle. He was the superintendent of schools and also the principal of the high school at the time. I had been to school about a month when he called me in his office. He said, ‘Clarence, just because you are my folks, don’t expect any easy things out of me.’ Among the other things, he counseled me and said, ‘Anybody with the guts you have has no business just loafing around and wasting your time. This work that you have done is not satisfactory. I want you from this time to learn to do the things that are hardest for you.’

“I was very active in athletics. I played basketball three years while I was in high school. I was probably the shortest center that Wayne High ever had! I played center all three years I was in high school. In the summertime, I used to play baseball. I was issued a baseball suit for the Fremont town [team] when I was thirteen years old. I treasured this very highly. I was certain nobody was going to get that suit away from me. I about killed a horse off a time or two, riding from out of the mountains to get to town on the Fourth of July for fear they would have my suit on somebody else.

“[While] in high school, during the summer months, I learned to play [the] drums by having some drumsticks I had fashioned out of rounds [from] chairs, which I made myself. Then I found an old frying pan that I tied on my saddle. As I would get off to just sit in one place to watch the sheep, I would pound on this frying pan. I drummed up enough rhythm that I became a drummer [for] the high school band through this way of learning. In my junior and senior years, I took the leading part in the high school operas. Joseph Hickman evidently had an impact.”[27]

George Wilson McConkie

George Wilson McConkie was born in Moab [Kane County, Utah] on 30 June 1909. He and his children were highly educated, but George wished he had gone farther: “I went through grade school at Moab and La Sal. [At] the school in Moab the grades were separate, but [in] La Sal we had two teachers teaching the eight grades in the church house. The church was [also] the school building.

“Some of the seventh- and eighth-grade boys were much bigger than the teachers and the principal of the school. I remember once or twice when the principal took a licking from some of those rough and tough boys. I remember the trips to and from school in the cold part of the winter. My younger brother [Andrew Ray], my older sister [Ina], and I rode a horse back and forth through the snow; all three [of us] on one horse [rode] through the deep snow. There were no homes in the two miles between our [home] and the school. My brother rode the tail end of the horse, and often he would find himself in the snow bank somewhere as he dropped off.

“We would have snow [as deep as] two feet. One of our pastimes during recess or the lunch hour [was to] go out in the sagebrush around the schoolhouse and catch rabbits as they jumped out from under the brush. They could not run in the snow, and we would [catch] them.

“As a rule, in those days, teachers were a little tough. I remember one especially in the sixth grade. He used to whip the students with a hose. He had a piece of rubber garden hose about three and one-half feet long and it was split into four or five strips. He would use that as sort of a cat-o’-nine-tails, and he really laid it on. It was mainly [because] a student whispered and [was] talking to his neighbor. Things were quite different then.

“I attended high school [in] Moab. I played football during my high school days. When I graduated, there were thirteen [students] in the graduating class. The fall following my graduation, I [entered] BYU. I didn’t have money enough to go straight through [four years]. I [completed] the first year and then worked for a while. Then I would go back [to BYU]. I got in a total of about seven quarters at BYU, after which I decided definitely to go into civil engineering and changed to Utah State Agricultural College [in] Logan. Of course, many of my BYU classes didn’t count towards an engineering degree, which required 210 quarter hours of prescribed work. As a result, I never graduated although I attended, I believe, seven quarters up [in] Logan. I had more college credit, but not all of the required [classes].

“At this [time], a chance [opportunity] came along, [and] I took the examination for a surveyor. I took this test [to] prove I was qualified under a test that was given all over the United States. From this test, I wound up with an appointment for geological survey [work].

“This was as good a job [as] most of our graduates from college were [finding] at the time. We[28] decided to get married, and it was probably one of the biggest mistakes of my life, not continuing with the school. The way it looked then, we decided to take the job. I had been working as an assistant on survey crews for quite a number of years [during] my schooling. That was how I made money to go to school.”[29]

Nathan Brindle Jones

Nathan Brindle Jones was born 27 December 1885 in Cedar City and later lived in Enterprise. He attended a one-room school in Enoch, near Cedar City. He recalled: “I was very young when I started to school. I was a barefoot boy [walking] in cockleburs and leaves. I went to school with Dave Sterling. If I remember right, it was just a one-room brick building, or adobe [blocks], with all eight grades in the one room and [with] one teacher. If she [had] just fifteen minutes with each class, she did well. You had to have a mind to not listen to the other groups and study your own book. [You had] to study by yourself to get any education.

“I enjoyed school quite a little when I was young, but after I was older, I didn’t. I didn’t keep up with school to learn as fast, because I was taken out to work and help make a living. I learned to read [better] after I quit school altogether than while I was going to school. I was fairly good in mathematics. I [0] that pretty well in school. I got more with my work. Even after I was married, I learned quite a bit about mathematics.

“When I was living in Enoch on [my] father’s farm, . . . we never could start school until the crops were in. The older boys were out making money for themselves. [Those of us who were] young fellows had to put in the crops. The older ones helped with the living too. It just was very little [education] that I [received] because we had to work in the fall to gather crops. In the spring, [we had] to plant the crops before the school [year] was half over. We only got a few months’ break. We seldom [had] two or three months for school when we were young.

“Much of the time we were not home, even though we wanted to be. You had to get out and go make a living. I was helping father with his freighting to Caliente [Nevada] or to Pioche [Nevada] and the early days of Delamar [Nevada]. I was taken away from school in the winters. You didn’t get very much [education].”[30]

Leland Taylor

Leland Taylor was born on 6 November 1905 in New Harmony. He recalls his schooling there: “[It was] a small [building] with one large room. All the classes from one to [the] eighth [grade] were in the one room [with] the teacher. I wouldn’t have traded those experiences for any of the experiences they have in school nowadays that I am acquainted with. They were wonderful experiences to me. The only thing I resented was not being able to get any high school [classes]. I would like to have gone on, but we could not. There was no transportation for them. My oldest brother [had] some high school [education] and the next oldest [had] a little bit—not much. None of us [had] any high school [education] until it [came] down to the very youngest [in the family]. Times changed enough so that we could [have] them in school by moving to where the school was.

“They had to work, and they had to go to work early. I had to take the eighth grade twice. I always resented that. Elmer Taylor, my cousin, was the teacher when I went through the eighth grade. Later on in the summer, I was working with him and he said, ‘You could have passed all right, but I knew you couldn’t go to high school. It was better for you to have something to do this winter.’ So he flunked me in science. He flunked me in science to make me take it over again just so I wouldn’t be idle through the winter.

“The teachers had to teach all the grades. They couldn’t specialize in any one grade. They had to teach them all. It wasn’t an easy life. They didn’t get paid too well either. I can remember Laverna Englestead; she taught [school for] quite a while. Minnie Pace was one of the best teachers I ever had. We had the three Rs and history. I guess because I didn’t have too much education is one reason I like to read so well. My brother Lester [went to] the eighth grade. That is all the [education] he could ever get. But he [obtained enough] education to put himself in the [Utah] State Legislature.”[31]

Joseph Woodruff Holt

Joseph Woodruff Holt grew up on the family ranch and went to school in Hebron, a small rural town west of Gunlock. His story is quite a contrast with Florence McArthur Leavitt in her urban setting: “My first school was in Old Hebron. It is a ghost town now. My first teacher was Zera Pulsipher Terry. I went to school there one year with Zera Terry. I must tell about a little episode we had that winter. He was strict. We had lots of [older] students up in the higher grades. I was the only one [in that grade] in a room not much bigger than this room here. The school building was about twenty feet long and about fifteen [feet] wide at that time. He used to carry a big, long, three-foot [yardstick] ruler around all the time in his hand, I guess probably to keep it a little quiet. He would use it once in a while too. One day, I was doing something he didn’t like; he came up and he said, ‘Joseph, put out your hand on that desk there.’ I put my hand up and he held this big long ruler up. He came down on my hand, and when he started to come down I jerked my hand, and he came down and hit that desk and popped his ruler right in two. A lot of the students had to laugh, that was all! They couldn’t hold themselves! I made him mad, but he didn’t say any more. He just let it go at that, and that was the last of the rulers. I didn’t see any more rulers. That was my first experience in school.

“I went to school for about five months each year until I was about seventeen. When I was eight years old, I went to school up in Mountain Meadows [in the town of Hamblin]. That is another ghost town. The teacher at that time was old man [James Samuel] Bowler. He was the father of all these builders around here. He was a very good teacher. He used to try to get me to sing when I was a young [boy].”[32]

Irma Slack Jackson

Irma Slack Jackson was born on 14 February 1893 in Toquerville. Her mother died in childbirth in 1899. She reports her school experience: “I went eight years in Toquerville and graduated from the eighth grade. They had what [was] called the schoolhouse and the church building. The church building was used for the four younger grades. They had big, long benches that could seat about half a dozen [students]—just homemade benches. [There was] a box heater in the middle of the floor. I remember I was the only girl in the class. I wanted to sit on the end of the bench, and a cousin of mine [sat] next to me because I didn’t want to sit by any of the other boys. But it was all right to sit by my cousin. I would sit on the end of the bench.

“There were four grade rooms in the church. [It was] the only church that had them. [And there were] four grades in the schoolhouse, as they called it. I remember when I was in the fourth grade, our teacher was Nellie Woodbury from St. George. [She] came up there [to] teach. She put on a little operetta called Red Riding Hood. She made me take the part of Red Riding Hood. I knew every song from beginning to end. I [later] sang them to my [children].

“I remember when I was in seventh grade, we had Charles Petty. He was our teacher when I was in seventh grade. He [taught] the seventh and eighth grades. He had the fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth, but he took the sixth and seventh grades up to Zion National Park. There were no roads up there and no camps of any kind. It took us one day to get there. We spent one day there, and one day we came back home.

“For graduation from the eighth grade they gave a big, one-foot-square certificate. They did [that] in those days. It came from the state. We had to take a state examination to get out of the eighth grade in those days. Then I came down here to the Dixie Academy.”[33]

Rhoda Hafen Leavitt

Rhoda Hafen Leavitt was born on 19 January 1906 in Bunkerville. She was able and strong-willed, as these stories show: “One day one of the boys, Dee Houston, came [into the school] and sat with me. Mr. Whiting [the principal and the teacher] came in and looked at me and said, ‘Rhoda Hafen, will you please take another seat?’ I said, ‘No, I will not. I am in my own seat. If anybody moves, it will be somebody besides me.’ He turned on his heel and walked back into the office. If I had been out of my seat, I would have moved, but I was not. So I did not. He could see that he was in the wrong. He sent one of the teachers back in there, [who] asked me to come in there. He said, ‘Why did you not move when I told you?’ I said, ‘I would have if I had been wrong, but I was not in the wrong. Dee was out of his seat, not me.’ He said, ‘I thought I could correct a girl a lot quicker and get by with it.’ I said, ‘No, you did know that I was in my seat.’ He said, ‘I guess you are right. I apologize.’

“The school in Bunkerville by then had each class in a separate room. Rhoda met Mr. Hutchings, one of the teachers there a few years later, and he said that her group of students were the smartest he had ever met. “He was a good teacher. He said, ‘We did not have many books, but we really made the best use of them. That one year I taught here, there was not a high school in the state of Nevada that went as high as those students did on their tests.’”[34]

William “Bill” Charles Pulsipher

William “Bill” Charles Pulsipher was born on 24 June 1895 in Hebron, but moved to Gunlock. “I was the oldest boy; we had two outfits, and I had to drive one of them. Dad drove one, and I drove one. After I [was] a little older, I wouldn’t go to school, [and] I got so far behind. You [can’t] blame a fellow for that. We had it all fixed that I was going to start when school started. We were living on a ranch south of Gunlock. I said, ‘I will go up every morning to school. I have to catch up.’ A couple of days before school started, it just happened; everybody in Gunlock would be out of flour. Dad said, ‘We have a load of grain in Ox Valley.’ That is up in the mountains south of Enterprise. ‘Go up and get that, take it to Modena and get a load of flour.’ I got caught in a snowstorm and had to stay there four or five days and school started. When I got back with the flour, I wouldn’t even go to school. That is the way it happened. I wouldn’t dare go back to school and be in class with youngsters who were two years younger than me. I have gotten by and have made a good living. I am not smart.

“My wife had one or two years of high school. I did like school when I was going and didn’t have to keep staying out every day or two. When I would have to stay out a day or two and then work to catch up or skip it, it wasn’t fun. The only fun I had in school was playing ball. It wasn’t basketball in those days; it was baseball. I had the best teachers in the world. My first teacher was Annie Miller from St. George. There wasn’t a kindergarten; I went to first grade. The second teacher was Zera Terry. He lived right there and has been a teacher his entire life. He beat me on the head more times than—I wasn’t much of a cutup. I didn’t like to [go] out and steal chickens and raise hell like that. The most fun I had was playing hooky from school, going out in the hills and riding steers. I did pretty well in school, but I didn’t get an education.

“I was inclined to be a cowboy. My dad was one all his life, and he taught me how to rope from the time I was old enough to ride. By the time I was fifteen years old, I was driving cattle for top wages from my uncle. He had quite a herd there.

“They held a religion class for a half hour every Thursday afternoon. It was not taught by the schoolteachers. I had an uncle who came there. He would come and teach the religion class. The teacher would just hold us there, and she would stay. I quite enjoyed that.”[35]

Rosalie Maurine Walker Bunker

Rosalie Maurine Walker Bunker was born on 9 May 1927 in Sunderland, Durham County, England. She later lived in Bunkerville and Logan and gives a view of what the schools were like that she attended in England. “The infant school would be kindergarten through maybe the first and second grades. When you were seven years old, you went into what we call the junior school for two years. You would be about nine years old when you finished. I think that was when we had divided classes. The boys went to the boys’ school, and the girls went to the girls’ senior school. We wore uniforms. When we were eleven years old, we had to sit for this scholarship examination. We went to the secondary school for about three days to take all these examinations. Only so many passed. We would not know if we passed until we saw our name in the newspaper.

“Following the next summer’s vacation, we would go to the secondary school. I think at the time the reason I wanted to go to secondary school was because they had six week[s] of summer vacation and the other school had only four weeks. To me, that was the big thing to grab, and it was a nicer school too. It had gardens and playgrounds. It was near our home too.

“Those who did not pass the examination would stay and go on to the ordinary school and leave when they were about fourteen years old. It used to be fourteen, and then they raised the age to fifteen. They would study ordinary subjects—geography and history. They did not study foreign languages like they did in the secondary school or take chemistry.

“The advanced school would get the cream of the students. My French teacher used to drum it into us that we were the cream of the crop. I guess there were about ninety girls who would go each year to the secondary school. There were three grades there. I always did like school. In secondary school we had a different teacher for each subject and French class. We did not start Latin until we were in the second grade. Then we took chemistry and physics, subjects that we had not had before.

“For some students who did not pass to go to secondary school, there was another school that they went to. They did more secretarial work, like typing.”[36]

Vernon Worthen

Most of these interviews were with people who recalled their school days as students. There are, however, some who reported their experiences as teachers. Here is an interview from one of the best-known teachers, Vernon Worthen, who was born in St. George on 19 April 1885. People who live in St. George now or who visit there will recognize his name as that of the city park. Here are some reminiscences from him: “After teaching school in Glenwood one year, I returned to St. George and taught the sixth grade [at Woodward School]. The principal was Edgar M. Jensen. A number of the teachers were Misha Seegmiller, Leland [‘Lee’] Hafen, Jedd Fawcett, Florence Foremaster, [and] Emma Foremaster. [1] continued teaching there until 1927, when I was asked by W. [William] O. Bentley, who was the superintendent of schools, to be principal of the elementary school, which included the eighth grade in the old Woodward School.

“In 1936 [Washington] County decided to change the program of the school, making it a six-four-four plan, with six elementary schools, four junior high [schools], two high schools, and two junior colleges. I took the [West] elementary school. I taught in the new school building from 1936 to 1955; that was [at] 100 West and Tabernacle, and I moved to that school.

“I had as high as twenty-three teachers and over six hundred students. I taught school for forty-one years [and] enjoyed every moment of the time that I was teaching. I had many experiences in school, civic, and community activities. . . . All my life, I’ve been very fussy about punctuality. While I was bishop, I told people if they would be there at 2:00 [p.m.], we would dismiss at 3:00. If they wanted to come at 2:15, we would stay an extra fifteen minutes. My policy [was], and I know that the teachers at school and my PTA officers made this statement, ‘We knew when you had a program at the school, if you said 7:30 [p.m.], you meant 7:30, instead of dragging on until the crowd got there.’ They said, ‘We knew we had to be on time.’” That was Mr. Worthen’s policy at the schools he led and at the many civic activities he was in charge of. After teaching for four decades, he became the city postmaster and then a full-time gardener.[37]

Robert Parker Woodbury

Here is the story of a nervous teacher, Robert Parker Woodbury, who was born 17 January 1873 in St. George. His brief remarks, at age ninety-five, give an interesting insight: “My first school [teacher] was a widow woman by the name of Sister Everts. She had the school in her home. That was my first school [experience], and I enjoyed it very much. I went through grade school and to what they called the St. George Academy. Later on, I moved to Cedar City and took [the] Normal Training Course. I graduated from [there]; then I came back to Washington County and taught school [for] fifteen years.

“I liked it. I like [students]; I like to make [things] for the [youngsters]. I had the ungraded schools. Sometimes I had all the grades. It worked on [my] nerves, and I [became] a little nervous. I [was] so nervous when the [children] made a racket in the house. Sometimes I would scold them and tell myself [that] maybe I had better quit teaching school. It affected me that way, and so I quit. I took out a loan and bought a farm on a government farm loan and farmed the [rest] of my life.”[38]

Elizabeth “Libby” Leany Cox