Oliver Cowdery's Legal Practice in Tiffin, Ohio

Jeffrey N. Walker

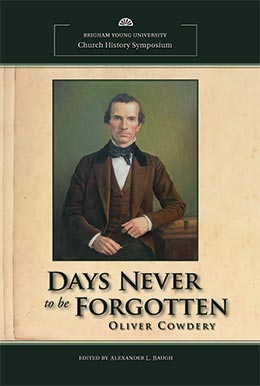

Jeffrey N. Walker, “Oliver Cowdery’s Legal Practice in Tiffin, Ohio,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 295–326.

Jeffrey N. Walker was manager and coeditor of the Legal and Business Series for the Joseph Smith Papers Project and an adjunct professor in the Department of Church History and Doctrine and at the J. Reuben Clark Law School at Brigham Young University when this was published.

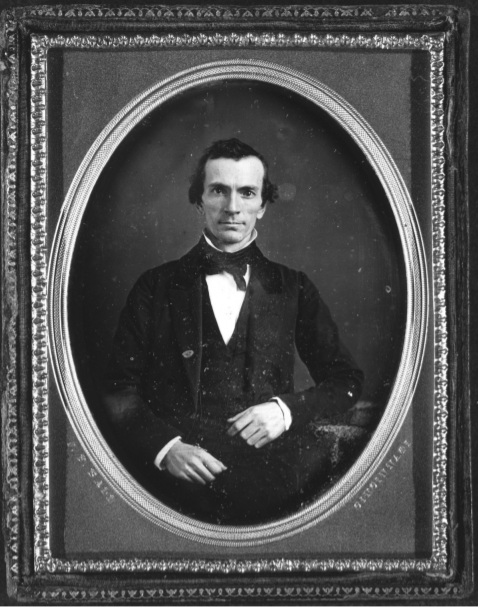

This is a recently discovered image that is probably of Oliver Cowdery. Cowdery was living in Tiffin, Ohio, practicing law during the time J.P. Ball, one of the first black daguerreotypes in the United States, was traveling throughout Ohio taking daguerreotypes of prominent people.

This is a recently discovered image that is probably of Oliver Cowdery. Cowdery was living in Tiffin, Ohio, practicing law during the time J.P. Ball, one of the first black daguerreotypes in the United States, was traveling throughout Ohio taking daguerreotypes of prominent people.

During the summer of 2006, I began preparing to speak for the Oliver Cowdery Symposium at Brigham Young University celebrating Cowdery’s two hundredth birthday. I was asked to speak on Cowdery’s work as an attorney. I knew that his law practice ran virtually concurrent with his years outside of the Church. As I gathered the various materials written about Cowdery during this period, I was greatly assisted by the groundbreaking work originally done by Stanley R. Gunn and then expanded by Richard L. Anderson.[1] Their excellent research, combined with the work completed by Scott H. Faulring[2] about Cowdery’s return to the Church, provided a significant foundation to understand his life. Knowing that I ran the real risk of merely repackaging the work of these worthy scholars, I struggled to find room for my own contribution.

Based on the suggestion of my good friend, Gordon A. Madsen, I called Richard Anderson for direction. Having been working as the manager and co-editor of the legal series for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, I was already fully engaged in studying the specifics of lawsuits involving Joseph Smith. I knew that Oliver Cowdery lived in Tiffin, Ohio, for more than eight years practicing law after leaving the Church. I wondered what Gunn, Anderson, and Faulring had discovered regarding Cowdery’s legal practice in Ohio. As I spoke with Professor Anderson, I was most interested in his visits to Tiffin in the late 1960s and early 1970s and the research he completed while there. In addition to his thorough review of all newspapers of the period, Anderson confirmed that he knew that there were papers in the local courthouse of Cowdery’s legal practice. Sensing my intrigue, he cautioned me about these records, sadly recounting that during previous years he had seen many repositories raided by collectors looking for documents signed or written by early Latter-day Saint Church leaders—Cowdery included.

I started making some additional inquiries, including contacting Heidelberg College in Tiffin, the Tiffin Seneca Public Library, the Seneca County Historical Society, and the Seneca County Museum. I confirmed that there were old legal files kept at the Seneca County Courthouse. I learned that this courthouse, built in 1884, was closed and was to be razed in order to build a new one. I also learned that the historical community was rallying in an attempt to save the building.

With so much in flux, I decided that time was of the essence to compile Cowdery’s law practice in Tiffin. While I anticipated finding minute and record books[3] (these are typically bound volumes that are regularly kept), I was stunned to find entire case files still tied together with ribbons.[4] In all the legal papers we had compiled for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, we had yet to locate a complete file for any of the cases we identified. The ensuing weeks were exciting. Initial estimations were that there were more than a thousand pages of pleadings where Cowdery or his law partners were counsel. By the time we had finished, more than 2,300 pages had been scanned and cataloged.[5] It was an amazing find.

It has been a humbling experience to review page after page written in that careful handwriting that matched the transcribed pages of the Book of Mormon. Perhaps I had indeed found a place to make a contribution. The ensuing months were a wonderful time as I made my first indexing and summary description of these cases.[6] Reading these files, I found an unanticipated kinship with Oliver. His practice encompassed the full spectrum of a country lawyer’s practice. He represented both plaintiffs and defendants in criminal and civil matters. Furthermore, his pleadings evidence a keen understanding of the unique nuances of practicing law in the 1840s.

In my efforts toward understanding the legal practice of the early 1800s, I found myself almost having conversations with Oliver Cowdery about the facts and the procedure or legal precedents of a case. His practice covered a unique period in the development of the “American System” of law.[7] Before 1848, the courts in America were direct descendants from the English courts of the King’s Bench and Common Pleas.[8] Commencing a case was permitted only thorough a complex use of writs. Exacting language was required, thereby making form books a necessity. Dozens of available writs were separated into real,[9] personal (further divided into contracts[10] and torts[11]), and mixed claims.[12] Cowdery’s practice evidenced a creative and broad understanding of the law and procedures available. At times, I was surprised at his approach to a case, using what I found to be obscure writs and processes.[13] As I commenced my study of his law practice, I became more and more intrigued about Cowdery as an attorney. What drew him into the practice of law? How long was he actually involved in the profession?

Oliver Cowdery’s path to the legal profession is inherently intertwined with his role in the founding of Mormonism. Any examination of his law practice must start with reviewing his pivotal role in the Restoration. He is remembered as the second elder of Mormonism, and oftentimes the sole companion to Joseph Smith at foundational moments of the Restoration, such as during the translation of the Book of Mormon, the restoration of the Aaronic and Melchizedek priesthoods, and the vision of Christ and the Old Testament prophets in the Kirtland Temple. No one else stood in a more unique position either to support or expose the Prophet. And Cowdery clearly understood the unique position he held in the Restoration. “Being the oldest member of the Church,[14]” he wrote to Phineas Young in 1848, “and knowing as I do, what she needs, I may be allowed to suggest a word for her sake, having nothing but her interest in view.”[15] As a consequence of being present during these seminal moments, the credibility of Oliver Cowdery is significant. It is therefore important to understand his character and access his reliability—much of that defined by his professional life while outside the Church.

His years in Kirtland marked the pinnacle of his career within the Church. He led the first missionary efforts through Ohio in 1830, which ultimately led to Kirtland becoming the headquarters of the Church for more than seven years. These efforts also led to the conversion of key future leaders, including Sidney Ridgon, Edward Partridge, Isaac Morley, John Murdock, Lyman Wight, Frederick G. Williams, and others. In December 1834 he was called by Joseph Smith to be the Assistant President of the Church, a position he held until his excommunication in April 1838. During the years 1830–38, Cowdery was involved in virtually every aspect of the movement in both Missouri and Ohio.

It was also during this time that Oliver first began to have an interest in the law. Before that time, he was employed principally as a schoolteacher and publisher, interests that he retained throughout his life. However, it was the law that drew his professional efforts for much of his adult life. For a three-month period in 1836, Cowdery kept a diary. His entry for January 18, 1836, contains what appears to be his first recorded notation for looking at the law as a vocation: “Recorded blessings until evening, when a man came in by the name of Lee Reed, and said that he had been sued for an assault, and that his opponent had sought thus to destroy [sic] him: he urged me to go before the court and plead his cause. On examining the same before the court, I saw the man was guilty of a misdemeanor, and could not say but little in his behalf. He was finally bound over to await his trial before the court of common Please [sic]: this descission was just, for he was guilty of throwing a stick against a little child.”[16]

This interest possibly resulted in his election on May 15, 1837, as a justice of the peace for Kirtland, a position he held until August 1837, when he moved his family to Far West, Missouri.[17] During these three months, Cowdery heard two hundred forty cases.[18]

In Missouri he aligned himself with his close friend and brother-in-law David Whitmer, president of the Church in Missouri.[19] By January 1838, Cowdery began making definite plans to practice law. That month he wrote to his brother Warren that he had obtained some law books to study, including “Black Stone 2 Vols. Kent 4 Vols., Commy and Doc., Starkie on Evidence 2 Vols., Story’s Commentaries I Vol., Wheaten’s International, Ohio’s reports, Missouri Doc. Statute 1 Vol. and have sent and expect in March between 50 and 60 vols more.”[20] On March 10, 1838, he again wrote to his brothers Warren and Lyman in Ohio, confirming that he anticipated receiving “some 55 volumes,” stating:

When I become acquainted more familiarly with the leading lawyers of the county, and the practice of the courts, if you are not here in the interim, will write you more fully. I have read some of the Supreme Court reports of this state, and think, generally, they will evince a very good knowledge of law. How I shall like the practice of the inferior courts, I cannot say. . . . I am pursuing my study as fast as health and circumstances will permit and hope I may feel competent to apply for a license in this summer.[21] If I do I shall have to go down the country to see one of the Judges of the Supreme Court, or attend the court itself which does not sit very near. The circuit attorneys are elected by the people—I have no doubt if L. [Lyman] was here he could get the office very soon.[22] If we can live here in peace we can grow up with the country and have our full share of publick matters.[23]

This letter also noted that Cowdery apparently was already lining up legal work: “We [Cowdery and Lyman E. Johnson] have some four or five suits to attend to at the next term of the Circuit Court (2nd of April); but we will have to employ some one to advocate the suits in open court.”[24] At this point neither Cowdery nor Johnson were members of the Missouri bar, but they had already started to get clients. Perhaps this is the reason Oliver was trying to entice Lyman, already a lawyer in Ohio, to come to Missouri. The statutes governing the practice of law were very clear, and Cowdery and Johnson apparently understood that they could not appear in the circuit court without a law license.[25] Interestingly, the law in Missouri required a license to practice law only in courts “of record.” Justice courts were not courts of record; therefore, under the governing statute, nonlicensed attorneys did not require a legal license to represent a party.

By spring 1838, Joseph Smith, his family, and other key leaders had abandoned Kirtland and moved to Far West. Simultaneously, antagonism between Thomas B. Marsh, David W. Patten (members of the Twelve), and the Missouri high council against David Whitmer, W. W. Phelps, and John Whitmer of the Missouri presidency reached a head, with Oliver aligning himself with his Whitmer relatives. The disputes between these men and groups festered into both apostasy and excommunication of Oliver, the Whitmers, and several others.

In April 1838, Oliver Cowdery was tried before a high council court and excommunicated. He did not attend the hearing, claiming that in his role as Assistant President of the Church the high council lacked jurisdiction over him.[26] Nine charges were brought against him. Counts one and seven dealt directly with Cowdery’s interest in or participation as a lawyer: “1st, For stirring up the enemy to persecute the brethren by urging on vexatious lawsuits[27] and thus distressing the innocent,” and “7th, For leaving the calling, in which God had appointed him, by Revelation, for the sake of filthy lucre, and turning to the practice of Law.”[28] While Cowdery did not substantively defend all the charges, he did submit a letter addressed to Bishop Partridge requesting that the council “take no view of the foregoing remarks, other than my belief in the outward governments of the Church.”[29]

After Cowdery’s excommunication in April 1838, he continued to explore practicing law in Missouri, possibly moving away from Far West to Daviess County. These options ended abruptly in June 1838, when Sidney Ridgon purportedly authored a lengthy ultimatum to the recent dissenters, including Oliver Cowdery, threatening that they “have three days after you receive this communication . . . for you to depart with your families peaceably; which you may do undisturbed by any person; but in that time, if you do not depart, we will use the means in our power to cause you to depart; for go you shall.”[30]

While a number of those purged during this time actively turned against the Church, Cowdery bowed out gracefully, temporarily relocating to Richmond in Ray County where he concentrated his efforts on leaving Missouri, possibly to Springfield, Illinois, to further his preparations to practice law. In a letter dated June 2, 1838 (before his departure from Far West), Cowdery explained to his brothers his disappointment at having not received the law books as anticipated: “I suppose I could get some yet, but if I go to Ill. soon, I think I better defer for the present, as I presume they can be had cheaper there than here, besides a transportation back.” He continued, “I have already written you all the books I have. I shall probably get Chitty’s Criminal Law, Russell on Crimes, Selwyn’s Nisi Pricas, Hawkin’s Pleas of the Crown & some one on Chancery Practice—may be Maddock’s or Story’s Equity, and perhaps some others.”[31] Cowdery summarized his professional ambition in the law:

I take no satisfaction in thinking of practicing law with half dozen books. Let us get where people live, with a splendid Library, attend strictly to our books and practice, and I have no fear if life and health are spared, but we can do as well as, at least, the middle class. I have had little or no law practice to test my skill or talent; but were it editing a paper, or writing an article for the public eye, I should feel perfectly at home. . . . My present wish is to place myself in a situation to support my family, and help my friends, without addressing any more responsibility than possible. Were it not for the situation of things I should never want to leave this State.[32]

He further indicated that he spoke to other disaffected members about joining him in both his relocation from Missouri and his law practice:

L.E. Johnson writes this mail for his father or brother to help him to a law library; and probably will also write to W. Parrish and invite him to come to Ill. and go into the profession of law with him. Now, if <bro.> Lyman and myself were in a spirited place, bro. Warren near, with our old friends scattered about in the adjoining counties, we could be of material benefit to each other. I am satisfied, that we can live together as well as to live separate. What is life without society? And where is that to be found more agreeably than in the company of relatives, if dictated by the principles of honor and honesty?[33]

By August 1838, Cowdery made his final plans to leave Missouri. Yet, instead of looking to Illinois, Cowdery decided to return to Ohio to be near his family and practice law with his brother Lyman. In this regard, Lyman counseled Cowdery on August 21, 1838: “Yesterday the Supreme Court commensed it Session in this County, I was admited <an Atty> to all the Courts in this state, and to day have Recd $7.00 in cash if you had been hear you would now of been admitted to, and not only that, you would of earnt sufficient to supported yourse<lf> & family Silvester has more than don it and besides made great proficientcy in his study, he would have a good examination.”[34]

Lyman further encouraged Cowdery’s move “back home,” noting “I would go to your place but I do not see as I could do you the good that you would do your self by comeing here.”[35]

Oliver moved back to the Kirtland area by late 1838.[36] There he started his study of the law in earnest under the tutelage of Benjamin Bissell, a prominent attorney in Painesville.[37] Cowdery was well acquainted with Bissell, who previously represented the Church’s interest in various lawsuits while headquartered in Kirtland, including assisting Joseph Smith’s escape from a mob in Painesville. Oliver studied law through 1839, was admitted to the Ohio bar,[38] and commenced practice with his brother Lyman as early as January 1840.[39]

During this time, Cowdery became politically active in the Democratic Party in the Kirtland area. This included being chosen as a delegate for Geauga County for the bicounty senatorial convention where Benjamin Bissell was elected a state senator. It appears that these political activities led him to Tiffin in 1840. Lang explained Cowdery’s introduction to Tiffin: “In the spring 1840, on the 12th day of May, he [Oliver Cowdery] addressed a large Democratic gathering in the street between the German Reformed Church of Tiffin and the present residence of Hez. Graff. He was on a tour of exploration for a location to pursue his profession as a lawyer. . . . In the fall of the same year he moved with his family to Tiffin and opened a law office on Market Street.”[40]

William Lang’s recollections conform to the pleadings discovered in the Tiffin courthouse. These records evidence a steady growth of Cowdery’s legal practice in Tiffin commencing in June 1840. A total of 138 cases were located. The following is a summary of these cases by year: 1840 (9), 1841 (10), 1842 (11), 1843 (18), 1844 (35), 1845 (28), 1846 (23), 1847 (3), 1848 (1).[41]

A sample summary log of the cases is included in the appendix. The next substantive step under accepted documentary guidelines will be to complete verified transcriptions of the documents and then annotate the transcriptions so that a reader can better understand both the substantive and procedural context of the cases.[42] I anticipate this process will take several years.

A survey of the decade that Cowdery spent outside of the Church (1838–48) permits an examination of his character outside the influence of Church dynamics. He accounted for this period to the Saints upon his return and rebaptism in early November 1848 in the vicinity of Council Bluffs, Iowa: “I feel that I can honorably return. I have sustained an honorable character before the world during my absence from you, this tho [sic] a small with you, it is of vast importance. I have ever had the honor of the Kingdom in view, and men are to be judged by the testimony given.”[43] Echoing this sentiment is William Lang in his eulogy of his mentor and colleague wrote in 1880:

Mr. Cowdery was an able lawyer and a great advocate. His manners were easy and gentlemanly; he was polite, dignified, yet courteous. He had an open countenance, high forehead, dark brown eyes, Roman nose, clenched lips and prominent lower jaw. He shaved smooth and was neat and cleanly in his person. He was of light stature, about five feet, five inches high, and had a loose, easy walk. With all his kind and friendly disposition, there was a certain degree of sadness that seemed to pervade his whole being. His association with others was marked by the great amount of information his conversation conveyed and the beauty of his musical voice. His addresses to the court and jury were characterized by a high order of oratory, with brilliant and forensic force. He was modest and reserved, never spoke ill of any one, never complained.[44]

Oliver Cowdery died on March 3, 1850. He was forty-three years old. Ironically, though he is one of the significant founding fathers of Mormonism, he spent nearly half of his adult life outside the Church. During the decade that he was silent in Church history, he made important contributions in his community as an attorney. In studying Cowdery’s legal practice, his integrity, ability, and capacity as an attorney are evident. As his legal papers are further studied, as his relationships with colleagues and clients are understood, and as his intellectual and professional skills are defined, I am confident that we will see more clearly what Joseph Smith saw as he called Oliver Cowdery his scribe, companion, assistant, and friend.

APPENDIX

Sample of Oliver Cowdery’s Tiffin, Ohio, Cases

Alphabetical Listing

|

File Date |

Caption |

Description |

Court/ |

| November 3, 1840 | Arnst (and wife) v. Sauder | Plea of Trespass on the Case Motion for “verbal slander” seeking damages of $1000 for alleging that Arnst’s wife was “a whore,” “a public whore,” “a damn whore,” “a prostitute,” “a public prostitute”—guilty of fornication and adultery. Case settled on February 26, 1842. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & J.M. May; then Cowdery & Joel W. Wilson for plaintiff; Sidney Smith for defendant |

| June 29, 1844 | Wolf and Bishop v. Blair | Amicable suit. Plea of Debt (Assumpsit). Written debt owed of $179. Blair is noted as a “cognovit”—confessor of judgment. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery for plaintiff; Joel W. Wilson for defendants |

| March 16, 1842 | Bogard v. Avery | Plea of Trespass—an assault—“violent blows and strokes,” “violently kicked,” “plaintiff greatly hurt, bruised and wounded, and became and was sick, sore, lame, and disordered, and so remained and continued for a long space of time.” Defense was self-defense; subpoena witnesses (11) for plaintiffs; sued to recover $1000; depositions taken and summary attached. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff; Rawson & Pennington for defendant |

| October 7, 1843 | Bowser v. Cromwell | Collection on a May 23, 1842, judgment of $57.34. Initially in the justice court, then transferred to the Court of Common Plea to exercise on real property. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff |

| October 1, 1842 | (Hannah) Boyer v. Shawhan | Plea of Trespass. Case about taking some yoke of cattle. Claimed damages of $75. Defendant files a demur claiming deficiency in the declaration, principally on the basis that the case had already been brought against another and non-suited. Case settled for court costs and $10 on account. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendants; Sea & Shall (sp) for plaintiffs. |

| April 9, 1842 | Thompson v. Brish | Plea of Assumpsit. Defense is offsetting judgment that Thompson had gotten against Brish in August 12, 1841. This case was a plea of assumpsit for a debt owed of $300 for goods. Case settles on August 20, 1842, with neither party taking anything. The file has a lot of pleadings on a prior case that was tried before a jury and had many witnesses. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant; Joseph Women (sp) for plaintiff. |

| June 28, 1841 | Chester (S. Waggone) v. McCartney and Rundell, executors for Dowse | Plea of Assumpsit. File includes a series of subpoenas (including one to George W. Smith and Joseph Smith [no relation] a transcript of the proceeding and exhibits (a written promise to pay for the oxen for $60), and JP finding for plaintiff. Judgment for plaintiff in the sum of $75, plus court costs of $3.75. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff; Sidney Sea for defendants. |

| November 20, 1843 | Cowdery & Wilson v. Spaugh, Bennett, and Williams | Collection against defendants for $20.34 and 1.95 in costs. JP judgment, upon execution found no personal property. Filed in Court of Common Pleas to go after real property. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson representing themselves. |

| November 3, 1840 | Cronise v. Betz | Plea in Trespass. Assault case. Cowdery files an interesting pleading noting that a deposition of Rueben Woods was lost in a fire at the courthouse. | Court of Common Pleas; Initially only Cowdery, then Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff; A. Rawson for defendant. |

| July 10, 1844 | Cronise v. Herrin | Plea in Assumpsit. Collection on a promissory note of $128.34. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| October 19, 1840 | Curtiss v. Murry | Bill of complaint. Curtiss claimed judgment against Mattheson. Bail was guaranteed by Crops (Mattheson’s father-in-law). Before Curtiss can execute against Crops, Crops assigns property to Murry. Curtis brings an action alleging fraudulent conveyance against Crops and Murry. Copy of deed is attached. | Court of Common Pleas; Wilson for plaintiff; Cowdery for defendant. |

| June 10, 1842 | Dutcher and Rough v. Hart | Plea in Assumpsit. Defense is a general denial, as well as a counterclaim for $300. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant. |

| September 1, 1841 | Elder, administrator of John Liver v. Caroline Livers | Elder reports to court of debts of Liver were greater than the assets of the estate. Petitions to sell some of the land that Liver own. Caroline is the wife and when he died he had two minor children. Issue centers on dower rights. Relevant deed is attached. Court granted motion to sell land. Advertising is attached. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for Plainiffs. |

| February 4, 1841 | Fisher v. Clay | Clay buys property subject to a trust deed and a series of promissory notes promising to pay $100 in four yearly installments to Heaton. Heaton then sells two of these $100 notes to Fisher who has brought this collection action. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| March 14, 1842 | Fleming, as administrator for estate of M. Schoch v. Burg | Plea of Assumpsit. Promissory note for $155.26 and another $200 lent by Schoch to Burg. Judgment in favor of plaintiff. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| April 4, 1844 | Glenn v. Houch | Plea of Debt. Promissory note for $650. Defendant confesses judgment. | Court of Common Pleas; Plaintiff (Glenn) represented by R.M. Pennington; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant. |

| June 21, 1841 | Gordon v. Armstrong and Fisher | Plea of Debt. Promise to pay $110. Trigger to pay was when Harrison was elected president of United States. Defendants demur, claiming that the subject cannot be legally assigned to Gordon (cites law therein). | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendants; Joseph Tisward (sp?) for plaintiff. |

| May 26, 1841 | Gordon v. Cross | Bill of Complaint to collect on a judgment in the amount of $37.01. Claim of fraudulent conveyance of 40 acres to avoid collection. See Curtiss v. Murry for similar claims and parties. Defendant defaulted. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| July 27, 1841 | Goring v. Neikirk | Plea of Trespass. Assault and battery, including hitting with fists and sticks, kicking and ruining his clothing on two occasions. Could not work for twelve weeks. Claims damages of $2000. Defense is that plaintiff also assaulted defendant, but also that defendant only “gently and lightly tapped and touched” plaintiff. Plaintiff claims that defendant failed to fully answer declaration and sought judgment. Defendant’s counsel argues that he did and in fact, plaintiff did not properly respond to counterclaim of assault and sought judgment—good defense is to have some offense. Case settles by defendant paying the court costs to plaintiff in plaintiff’s case and vice versa. | Court of Common Pleas; Abel Rawson for plaintiff; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant. |

| April 25, 1844 | Graham and Graham (Graham & Co.) v. Michael | Plea of Assumpsit. Damages of $150. Collection on a promissory note in the amount of $200. Note was assigned to plaintiff from Lloyd Sons. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiffs. |

| October 26, 1840 | Hollister v. Tuckerman | Plea of Assumpsit. Collection of $500 debt. For goods and services (work). Defendants counterclaim for $400 for goods and services. Settlement of both claims with a judgment against Tuckerman for $150. | Court of Common Pleas; Abel Rawson for plaintiff; Wilson & Cowdery for plaintiff (Wilson’s handwriting). |

| June 28, 1841 | Ives v. Miller and Miller (W&L Miller) | Plea of Assumpsit. Collection on a promissory note in the amount of $95. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| March 23, 1844 | Jeffery v. Bartlett | Deposition transcript—interesting format—questions and answer. About a $50 promissory note. Also interrogatory requests prepared by Cowdery. | Court of Common Pleas; Rawson & Pennington for plaintiff; Cowdery & Wilson for defendants. |

| November 4, 1842 | Koons v. Lawrence | Judgment for plaintiff of $79.86, with $2.89 in costs. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| August 24, 1840 | Lamberson v. Pettys | Plea in Assumpsit. Collection on note for $55. Judgment for plaintiff for $17.50 and costs of $7. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant; Sidney Smith for plaintiff. |

| September 16, 1840 | Lease v. Manly | Plea of Trespass on the Case. Fraudulent conveyance action. Lease had gotten a judgment against Manley. Manley conveyed his property to his minor son after the judgment. Plaintiff joins both father and son to action. Moves the court to appoint a guardian ad litem for minor child. Cowdery moves the court to serve by publication. Guardian ad litem answers claiming that the minor child knew nothing about the conveyance. Cowdery & Wilson takes depositions. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery for plaintiff; then Cowdery & Wilson. |

| June 28, 1841 | Long v. Waid | Plaintiff sues Waid, a justice of the peace. Claim of malfeasance against the justice as a result of his refusal to accept security (bail) as required by a statute for a claim brought by a women claiming that he was the father of her unborn child (statute for the support of illegitimate children). | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| June 24, 1840 | Mathewsen v. Boyd | Plea of Trespass. Assault claim. Damages of $500. Appears to settle for $14. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery for plaintiff; then Cowdery & Wilson (by 5/ |

| April 3, 1844 | McDargh v. Riker | Case arbitrated. Case about debt owed for stone provided and installed for a wall. | Justice Court; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| March 23, 1843 | Meyer v. Shaney | Collection on a promissory note. The wife of the plaintiff loaned $118 to her brother and received a promissory note. She took ill and died without any children. Before her death she gave the promissory note to her husband. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| May 3, 1843 | Pierce v. Scholk and Bucher as administrators for Scholk | Plea of Assumpsit. Collection on a promissory note in the amount of $150. Defendants move to quash for failure to properly plead the cause. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for defendant; Richard Williams for plaintiff. |

| November 28, 1843 | Plummer v. Berry | Plea of Assumpsit. Collection of a promissory note for $115. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| June 15, 1844 | Powell v. Selby, et al. | Plea of Trespass. Claim of theft of a cow, a horse, a mare, a gelding and a plow valued at $200. Selby admits only that he took one mare and counterclaims against Powell that he, the treasurer for a school board, collected and failed to pay school taxes, and that the subject mare was sold to Selby to pay for the tax. | Court of Common Pleas; Rawson & Pennington for plaintiff; Cowdery & Wilson for Selby, only. |

| July 4, 1844 | Rosegrant v. Spangle (Bennett) | Collection of a Justice Court case judgment of $40.35. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| June 24, 1841 | Rosegrant v. Spangle, Bennett, Will | Plea of Trespass. Assault (“many violent blows and strokes” was down for “four weeks”) claiming damages of $1000. Case settles on August 17, 1842, for $50 to plaintiff and $50 to plaintiff’s counsel. | Court of Common Pleas; Sea, Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff; Boalt & Rawson for defendants. |

| December 9, 1842 | Saltsman v. Berry | Bill of merchandise. Collection case for $31.34, plus costs. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| May 21, 1841 | Sauter, as administrator for Faulhaber v. Faulhaber | Debts of Faulhaber more than his estate. Widow remarried. Has 6 children (one married). Petition to sell land to satisfy debt. Motion to join widow and heirs. Petition moves to have one son served by publication because they can’t find him. Give notice to everyone in newspaper (clipping attached). | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff (petitioner) |

| May 13, 1841 | (George W.) Smith v. (Jesse) Miller | See above suit where Smith was witness for plaintiff. Smith loans Miller $225, secured by a mortgage. Further, that J. Miller transferred property to L. Miller. Interesting exhibits (“copies”). | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| January 31, 1842 | Spitler v. Spitler, et al. | Spitler (plaintiff) is the son of the defendant, Spitler, his mother. Son pays mother $100 for property. He occupies the land until his father and mother die. There is a dispute pertaining to who owns the land. Suit brought is quiet title. Moves to have William Lang to be appointed guardian ad litem over all the minor sons/ |

Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for petitioner; William Lang for M. Spitler (initially). |

| April 14, 1842 | State v. Davis | Underlying case brought against Davis and J. Peterson/ |

Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for complainant; Rawson & Pennington for Foster. |

| September 30, 1840 | State v. Gingery | Indictment for petit larceny. This case is about Gingery not appearing and the forfeiture of his bail bond. Gingery defense is that while he was taking J. Willes home because he was ill he took ill too. Affidavit of Willes (interestingly shows affidavit drafted by Cowdery, but signed by Willes). Cowdery appeals conviction and notes basis. | Court of Common Pleas; Sidney Smith for prosecuting attny; Cowdery for Gingery. |

| May 2, 1844 | Loseny, Sterling & Co. v. Sloane & Blair | Plea in Assumpsit. $800 owed for goods sold. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| September 19, 1840 | Stuckey v. Stuckey | Plea for Partition. Stuckley is brother of the deceased who died intestate. As an heir, he sought the partition of an 80-acre parcel so that he can have his 25%. Cowdery moves to serve by publication to the other heirs. Granted. Notice attached noting Cowdery & Wilson. Some pleadings in German. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery for petitioner; Cowdery & Wilson by June 30, 1841. |

| May 2, 1844 | Swift & Hurlbut v. Sloane & Blair | Plea in assumpsit. PN’s for $37.31, $126.31, and $200. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| May 6, 1843 | Wilson v. Poppleton | Plea in assumpsit. Joel Wilson, plaintiff, is Cowdery’s law partner. Promissory note for $106.67. Also loaned other monies. Damages of $200. Case settled for undisclosed amount. Defendants to pay court costs and matter withdrawn. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

| September 2, 1842 | Wilson v. Stout | Plea of the Case. Defamation suit. Joel Wilson is plaintiff. Damages of $1000. “Plaintiff is now a good, true, honest and faithful citizen of the State of Ohio.” Case settles with costs being paid by plaintiff. | Court of Common Pleas; Cowdery & Wilson for plaintiff. |

Notes

[1] See Stanley R. Gunn, Oliver Cowdery: Second Elder and Scribe (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962); and Richard L. Anderson, “Oliver Cowdery’s Non-Mormon Reputation,” Improvement Era, August 1968; Richard L. Anderson, “Oliver Cowdery, Esq.: His Non-Church Decade,” in To the Glory of God: Mormon Essays of the Great Issues, ed. Truman G. Madsen and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 199–216; and Richard L. Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981).

[2] See Scott H. Faulring, The Return of Oliver Cowdery (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997).

[3] Court records kept in the nineteenth century can be separated into three major categories: minute books, record books, and case files. Minute books include judgment dockets maintained by the clerk of the court. They included a summary of the procedural history of a case, including the final disposition (the judgment docket), but not the text of the proceedings. Consequently, they are the least significant to study. Record books were transcriptions or copies of the most important pleadings and documents in the case. These books are tremendously useful when the original pleadings and documents are not extant. The case files, as a general rule, are maintained by the court and contain all of the pleadings and documents submitted during the pendency of each case. Case files, therefore, are the richest source of information.

[4] Before staplers and paper clips, lawyers would trifold multiple pages of pleadings and tie a ribbon around them when they filed them with the court.

[5] Lisa Harrison and Dawn Harpster provided invaluable help in locating and organizing these pleadings.

[6] My daughter, Chelsea Pickup, has been transcribing these cases. Her careful and conscientious work continues to be critical in this process.

[7] The American System is a tiered court system. Under state law, small claims courts and district courts try cases. Courts of appeals and the state supreme courts review tried cases. It is a straightforward structure. In contrast, the system in place during Cowdery’s practice was a hybrid system of English courts, including Courts of Exchequer, Courts of Chancery, Courts of Oyer & Terminer, Courts of Common Pleas, Courts of General Sessions, Courts of Special Sessions and Justice Courts. Like the English system, these courts largely separated actions at law and suits in equity.

[8] Sweeping procedural changes in the practice of law in America occurred in 1848 with the adoption of the “Field Code” named after its principal author, Dudley Field. The Field Code effectively extinguished the distinction between actions at law and suits in equity, substituting this practice with one form of action denominated as a “civil action.”

[9] Real writs, which identified claims connected with real property, include (1) Writ of Right: an action, also know as pleas of land, brought to recover title to land by adverse possession; (2) Writ of Entry: an action to recover possession of land, similar to an unlawful detainer or hold-over tenant action; (3) Writ of Dower: an action for a widow to obtain her dower (one-third) interest in her husband’s real property for the remainder of her life; and (4) Writ of Partition: an action to divide real property and its sale for property held in joint tenancy or tenants in common.

[10] Personal writs referred to as ex contractu (“arising from contract”) include (1) Writ of Assumption: an action arising from the breach of an implied or express contract for money or services; (2) Writ of Account: an action seeking an accounting for profits or money owed under an agreement; and (3) Writ of Debt: an action brought to seek a liquidated damage under a contract (e.g., lease or mortgage obligation).

[11] Personal writs referred to as ex delicto (arising from tort”) include (1) Writ of Trespass: an action arising from a direct and immediate injury to a person or personal property; (2) Writ of Trespass on the Case: a catchall action when other writs don’t fit, often used for civil slander and libel actions; (3) Writ of Replevin: an action to recover personal property; and (4) Writ of Trover: an action to receive damages for losses of personal property.

[12] These mixed writs included the following examples: (1) Writ of Ejectment: an action for recovering possession of real property and seeking damages associated with the loss of possession; (2) Writ of Nuisance: an action arising from the disturbance or use of real property and damages associated therewith; and (3) Writ of Waste: an action for the abuse or destruction of real property.

[13] For example, in Wolf and Bishop v. Blair (Seneca County, Ohio, Court of Common Pleas, 1844), Cowdery represented the plaintiffs, while his partner Joel Wilson represented the defendants in a collection case (a Writ of Debt action). While this case appears to have an impermissible conflict of interest with the firm representing both parties, Oliver Cowdery brought the case as an “amicable action,” with Blair, the debtor, being “cognovits” (a confessor of judgment), effectively resolving any conflict.

[14] Oliver Cowdery was, in fact, the first person baptized in this dispensation, having first been baptized by Joseph and then baptizing Joseph on May 15, 1829, in the Susquehanna River.

[15] Oliver Cowdery to Phineas Young, April 16, 1848, as cited in Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 257.

[16] Leonard J. Arrington, “Oliver Cowdery’s Kirtland, Ohio ‘Sketch Book,’” BYU Studies 12, no. 4 (Summer 1972): 5. Interestingly, Oliver Cowdery did not become licensed to practice law in Ohio until 1840. It is unclear on what basis he was acting in representing Reed, since the law stated, “[N]o person shall be permitted to practice as an attorney or counsellor at law, or to commence, conduct or defend any action, suit or [com]plaint in which he is a party concerned” (Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, ch. 11, Attorneys at Law, sec. 1, enacted June 1, 1824 [1841]). Consequently, under Ohio law Cowdery could not represent Reed. This in contrast to the laws in other states such as Missouri, which allowed an unlicensed person to practice before justice of the peace courts as they were not “courts of record” (Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri, Attornies at Law, sec. 1, enacted Februrary 18, 1835 [1840]).

[17] Justices of the peace did not have to have any formal legal training. Justices were elected by townships to three-year terms (Constitution of the State of Ohio, article III, sec. 11 [1841]; Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, ch. 65, Justices’ Election, Resignation, Commission, Bond, etc., sec. 1 [1841]; The Township Officer’s and Young Clerk’s Assistance Comprising the Duties of Justice of the Peace [Columbus, OH: Thomas Johnson, 1836], 2).

[18] Cowdery was elected as one of two justices of the peace in Kirtland on April 29, 1837 (the other justice of the peace during this period was Frederick G. Williams). He took office on June 14, 1837, and served for three months and nine days, resigning on September 15, 1837. His older brother, Warren A. Cowdery, replaced him. Cowdery kept a careful docket book during his tenure as justice of the peace. This docket book is preserved in the Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Most of the 240 lawsuits he presided over were collection cases below the $100 jurisdictional limit for justice’s courts (Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, ch. 66, An Act Defining the Powers and Duties of Justices of the Peace, and Constables in Civil Cases, sec. 1, enacted March 14, 1831 [1841]). He also handled a handful of criminal cases, the most famous being a two-day trial in August where seventy witnesses testified arising from an altercation in the Kirtland Temple. Warren Cowdery added to this docket book during his subsequent tenure.

[19] Oliver and David’s friendship extended back to mid-1820s in New York where they both worked as schoolteachers. Oliver married David Whitmer’s youngest sister, Elizabeth Ann, on December 18, 1832, in Jackson County, Missouri.

[20] Oliver Cowdery to Warren Cowdery, January 21, 1838, Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

[21] Under Missouri law, to become licensed to practice law a person “shall produce satisfactory testimonials of good moral character, and undergo a strict examination as to his qualifications, by one of the [supreme court] judges” (Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri, Attornies at Law, sec. 2, enacted February 18, 1835 [1840]). Missouri had no time requirement for studying law before admission, as there was in Ohio. See note 38.

[22] Cowdery does not appear to be correct here. Circuit attorneys were selected by the Missouri Supreme Court and commissioned by the governor (Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri, Attorney General and Circuit Attorney, sec. 4, approved January 5, 1835 [1840]). Lyman Cowdery was admitted to the Ohio bar on August 20, 1838 (Supreme Court Journal, County of Chardon, State of Ohio, 324).

[23] Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, March 10, 1838, Huntington Library.

[24] Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, March 10, 1838, Huntington Library.

[25] The Revised Statutes of the State of Missouri, Attornies at Law, sec. 1 (1840), states, “No person shall practice as an attorney or counselor at law, or solicitor in the chancery in any court of record, unless he be a free white male, and obtain a license from the supreme court, or one of the judges thereof in vacation.”

[26] Cowdery articulated this general concern to Warren and Lyman by letter wherein he cited a March 10, 1838, letter to Thomas Marsh from David Whitmer, W. W. Phelps, and John Whitmer noting, “It is contrary to the principles of the revelations of Jesus Christ & his Gospel and the laws of the land, to try a person by an offence by an illegal tribunal, or by men prejudiced against him, or by authority that has given an opinion or decision beforehand or in his absence” (Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, March 10, 1838, Huntington Library).

[27] Both contemporary and historical commentators suggest that the term “vexatious lawsuits” as used here and other places meant mean-spirited or malicious lawsuits brought without probable cause. However, cases where less than five dollars was at issue were also referred to as vexatious suits and several states had even limited the ability to bring forward such cases or otherwise limit the action. For example, in Ohio cases that were brought to recover five dollars or less, the plaintiff could not recover costs (Revised Statutes of the State of Ohio, ch. 86, sec. 78 [1841]). It appears that it is within this context that the reference to vexatious lawsuits is being made. This is further supported from the testimony proffered during the hearing in which the complaints are against Cowdery wanting to do “collection” work. This kind of legal work, while certainly not vexatious in terms of it being malicious and without probable cause (the debt would actually be claimed to be owed), but rather for a small amount—something less than five dollars.

[28] Cowdery’s excommunication hearing was held on April 12, 1838, presided over by Bishop Edward Partridge. As indicated, Cowdery did not attend the hearing but provided a letter of explanation. The letter was read at the hearing wherein he denied many of the allegations, noting that he “wished that those charges might have been deferred until after my interview with President Joseph Smith” (Oliver Cowdery to Edward Partridge, April 12, 1838, as cited in Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983], 164). Testimony was heard from several persons including John Corrill, John Anderson, Dimick B. Huntington, George Hinckle, George Harris, and David W. Patten. Much of the testimony centered on Cowdery’s practice of law. Testimony included charges that he “had been influential in causing lawsuits in this place, as a number more lawsuits have taken place since he came here than before,” that he “went on to urge lawsuits as even to issue a writ on the Sabbath day also, that he heard him say that he intended to form a partnership with Donaphon who is a man of the world,” and that he “wanted to become a secret partner in the store” so he could act as an attorney and collect debts (Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 166–67). At the conclusion of the hearing, three of the nine charges were rejected or withdrawn. All the others were sustained, including the charges related to his legal activities, justifying his excommunication (Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 169).

[29] Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 165–66. Cowdery started the letter noting that “his understanding on those points [the charges] which are grounds of difference opinions on some Church regulations” (Cannon and Cook, Far West Record, 164). His feelings at the time were more openly expressed to his brother, Warren and Lyman in a letter dated February 4, 1838, where he commented about the upcoming council: “My soul is sick of such scrambling for power and self aggrandizement by a pack of fellows more ignorant than Balaam’s ass. I came to this country to enjoy peace, if I cannot, I shall go where I can” (Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, February 4, 1838, Huntington Library).

[30] Read by the Danite leader, Sampson Avard, during his testimony at the Court of Inquiry held in Richmond in November 1838, selections from this long missive include: “Whereas the citizens of Caldwell county have borne with the abuse received from you at different times, and on different occasions, until it is no longer to be endured; neither will they endure it any longer, having exhausted all the patience they have, and conceive that to bear any longer a vice instead of a virtue. . . . And you shall have three days after you receive this communication to you, including twenty-four hours in each day, for you to depart with your families peaceably; which you may do undisturbed by any person; but in that time, if you do not depart, we will use the means in our power to cause you to depart; for go you shall. . . . Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Lyman E. Johnson, united with a gang of counterfeiters, thieves, liars, and blacklegs of the deepest dye, to deceive, cheat, and defraud the saints out of their property, by every art and stratagem which wickedness could invent, using the influence of the vilest persecutions to bring vexatious law suits, villainous prosecutions, and even stealing not excepted. In the midst of this career, for fear the saints would seek redress at their hands, they breathed out threatenings of mobs, and actually made attempts with their gang to bring mobs upon them. . . . During the full career of Oliver Cowdery and David Whitmer’s bogus money business, it got abroad into the world that they were engaged in it. . . . Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Lyman E. Johnson, were engaged while you were there. Since your arrival here, you . . . set up a nasty, dirty, pettifogger’s office, pretending to be judges of the law, when it is a notorious fact, that you are profoundly ignorant of it, and of every other thing which is calculated to do mankind good, or if you know it, you take good care never to practise it. . . . And, amongst the most monstrous of all your abominations, we have evidence (which, when called upon, we can produce,) that letters sent to the post office in this place have been opened, read, and destroyed, and the persons to whom they were sent never obtained them; thus ruining the business of the place. We have evidence of a very strong character, that you are at this time engaged with a gang of counterfeiters, coiners, and blacklegs, as some of those characters have lately visited our city from Kirtland, and told what they had come for; and we know, assuredly, that if we suffer you to continue, we may expect, and that speedily, to find a general system of stealing, counterfeiting, cheating, and burning property, as in Kirtland—for so are your associates carrying on there at this time; and that, encouraged by you, by means of letters you send continually to them; and, to crown the whole, you have had the audacity to threaten us, that, if we offered to disturb you, you would get up a mob from Clay and Ray counties. For the insult, if nothing else, and your threatening to shoot us if we offered to molest you, we will put you from the county of Caldwell: so help us God.”

A total of eighty-three Church members, including a number of Church leaders, signed this letter. Interestingly, neither Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, nor Hyrum Smith of the First Presidency signed the petition (Document Containing the Correspondence, Orders, &C. in Relation to the Disturbances with the Mormons; And the Evidence Given Before the Hon. Austin A. King, Judge of the Fifth Judicial Circuit of the State of Missouri, at the Court-House in Richmond, in a Criminal Court of Inquiry, Begun November 12, 1838, on the Trial of Joseph Smith, Jr., and Others, for High Treason and Other Crimes Against the State [Fayette, MO: Boon’s Lick Democrat, 1841], 103–7). For a discussion of these documents, see Stanley B. Kimball, “Missouri Mormon Manuscripts: Sources in Selected Societies,” BYU Studies 14, no. 4 (Summer 1974): 458–87.

[31] Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, June 2, 1838, photocopy of original in Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 263.

[32] Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, June 2, 1838, photocopy of original in Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 263–64.

[33] Oliver Cowdery to Warren and Lyman Cowdery, June 2, 1838, photocopy of original in Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 265.

[34] Lyman Cowdery to Oliver Cowdery, August 21, 1838, Huntington Library.

[35] Lyman Cowdery to Oliver Cowdery, August 21, 1838, Huntington Library.

[36] Cowdery appeared as the secretary in the organizational minutes for the Western Reserve Teachers Seminary and Kirtland Institute on November 21, 1838 (Lake County Historical Society, Mentor, Ohio, microfilm copy, Perry Special Collections).

[37] William Lang, who studied law under Cowdery, recalled, “He came to Ohio when he was a young man and entered the law office of Benjamin Bissell, a very distinguished lawyer in Painesville, Lake county, as a student, and was admitted to practice after having read the requisite length of time and passed an examination” (William Lang, History of Seneca County from the Close of the Revolutionary War to July, 1880 [Springfield, OH: Transcript Printing Co. 1880], 364).

[38] Under Ohio law, a person may be admitted to practice law by being examined “by any two judges of the [Ohio] supreme court” (Ohio Revised Statutes, ch. 11, sec. 1 [1841]). The qualifications to be examined for admittance to the Ohio bar are articulated in section 3 of the same chapter, noting in part: “That no person shall be admitted to such examination unless he shall have previously resided one year within this state, and shall produce, from some attorney or counsellor at law, a certificate, setting forth that such applicant is of good moral character, and that he has regularly and attentively studied the law, during the period of two years, previous to his application for admission, and that he believes him to be a person of sufficient legal knowledge and abilities to discharge the duties of an attorney or counsellor at law.” Cowdery clearly satisfied the “residency” requirement, having moved to Ohio in late 1838 and was admitted in or about January 1840. However, it is less clear whether he studied law for the requisite two years. One must assume that Bissell permitted Cowdery to count some of the time studying law while in Missouri. As noted, Cowdery obtained a series of law books by January 1838, noting to his brothers by letter dated March 10, 1838, “I am pursuing my study as fast as health and circumstances will permit and hope I may feel competent to apply for a license in this summer.” See note 21.

[39] Richard L. Anderson noted that the earliest advertisement of Cowdery and Lyman’s practice is found in the Painesville Republican under the name “L & O Cowdery” dated January 20, 1840 (Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses, 47n5). However, Stanley R. Gunn, note that the earliest advertisement for “L & O Cowdery” was in the Painesville Telegraph, March 3, 1840 (Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 169, 201n15). Regardless, both of these scholars would agree that Cowdery was admitted to practice law in Ohio when he traveled to Tiffin in May 1840.

[40] Lang, History of Seneca County, 365.

[41] Gunn provides a partial listing of cases he identified from the Tiffin Courthouse records noting Oliver Cowdery’s practice (Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 183, 185–87). It appears that Gunn reviewed the judgment dockets (Gunn, Oliver Cowdery, 201n4). While Gunn used the dockets to note when a case was handled, the date of the judgment is when the case was resolved, not when it was filed. Traditionally, one looks at the filing date as to the date of the case.

[42] For a useful overview of the process of preparing these cases for publication using a documentary editing process, see Mary-Jo Kline and Susan Perdue, A Guide to Documentary Editing (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1998).

[43] Pottawattamie High Council Minutes, November 5, 1848, Church History Library.

[44] Lang, History of Seneca County, 365.