Images of Oliver

Patrick A. Bishop

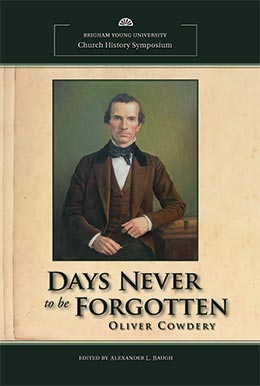

Patrick A. Bishop, “Images of Oliver,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 123–43.

Patrick A. Bishop was a Seminaries and Institutes of Religion coordinator for the Casper and Gillette Wyoming Stakes when this was published.

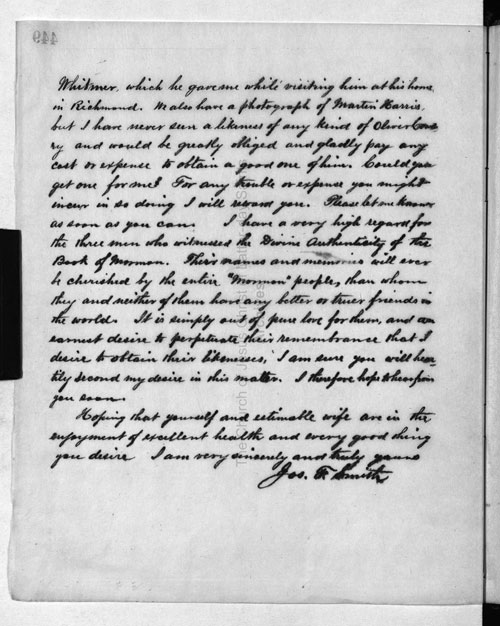

Second age of a letter signed by Joseph Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, January 31, 1883. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

Second age of a letter signed by Joseph Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, January 31, 1883. (Courtesy of Church History Library.)

On January 31, 1883, Joseph F. Smith, second counselor in the First Presidency, wrote a letter to James R. B. Van Cleave, a grandson-in-law to David Whitmer. President Smith’s desire was “to obtain an image in the likeness of Oliver Cowdery.” He stated, “We have the fine steel engraving of Father David Whitmer. . . . We also have a photograph of Martin Harris but I have never seen a likeness of any kind of Oliver Cowdery.” President Smith then went on to express that, “It is simply out of the pure love for Oliver, and an earnest desire to perpetuate his remembrance that I desire to obtain his likenesses.”[1] Smith went on to write five more letters to Mr. Van Cleave in his attempts to obtain a photograph of Oliver. His persistence and determination will ever be cherished by the Latter-day Saint people. Under President Smith’s direction, Elders John Morgan, James H. Hart, and Junius F. Wells joined in his desire to obtain a photographic likeness of Oliver Cowdery. Morgan investigated the possibility of a photograph even existing and found that one did. Hart was sent on a mission to obtain it, and Wells printed the engraving of the Three Witnesses in the frontispiece of volume 5 (1883–84) of the Contributor. The effort made by Morgan and Hart plays the largest part in the story and deserves more attention than has been given in the past.

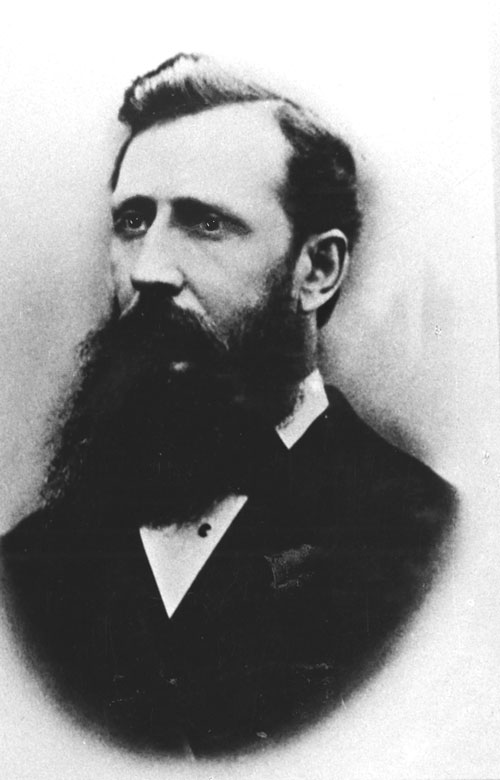

Left to right: Joseph F. Smith, John Morgan, James H. Hart, and Junius F. Wells.

In his March 29, 1883, letter to Van Cleave, Joseph F. Smith states that “a friend of mine has called at Richmond Mo. and has made arrangements with Mrs. Johnson to get photographs of her father, which will obviate the necessity of your doing anything in the matter.”[2] The friend referred to by Smith was John Morgan, president of the Southern States Mission. The woman referred to as Mrs. Johnson was Maria Louise Cowdrey Johnson, the only surviving daughter of Oliver and Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery. Morgan learned through correspondence with some friends of Elizabeth that “a daguerreotype had been taken of Oliver four years before his death, 1846, and that it, as well as the oil painting, was in possession of his daughter.” Morgan said that the daguerreotype would be loaned to them and would be in their possession in a few days; however, it was soon found out that Elizabeth’s husband, Charles Johnson, was very much opposed to the loaning of any image to the “Utah Mormons.”[3] Nonetheless, President Smith renewed his efforts and wrote Van Cleave again on April 24 to perhaps get a “crayon likeness of O. Cowdery.”[4] Smith wrote two more letters that were never answered. In the last of these letters, President Smith wrote, “I am a little perplexed that I cannot get any word from you in response to my last communications. I sincerely hope that I gave you no offense in my letter of Mar. 29th. I certainly did not intend it. I am very anxious to know whether you can succeed in obtaining the crayon likeness of O. Cowdery, and if not, whether I could get a photograph or some other likeness of him.”[5] In desperation, Elder Hart was sent to obtain the image of Oliver Cowdery.

In August 1883, Elder Hart, the Church immigration agent in New York City, left New York to return to Utah. En route, he traveled to Southwest City, Missouri, to meet personally with the Johnsons. On August 23, Hart wrote to the Deseret News:

“I am now enroute [to] South West City, which is 28 miles from Seneca. It is in the extreme Southwest corner of the State of Missouri, and is the present home of Oliver Cowdery’s widow and his only daughter, who is the wife of Dr. Charles Johnson. The railroad goes no nearer than this place [Seneca]; I have therefore to hire some private conveyance, and the trip will take me two days. The object of my visit is to obtain a Daguerreotype of Oliver Cowdery, one of the three witnesses, and his family have the only one in existence.”[6]

Upon arrival at the Johnsons’ home Elder Hart reports: “The doctor was at first quite hostile, but after laboring with him several hours, during which his wife and Mrs. Cowdery warmly seconded my pleading, some kind spirit came upon him and he gave me the choice between the  oil painting and the daguerreotype. I chose the latter, and placed it in the hands of the engravers. Before I left, the same spirit led the doctor to say he thought perhaps he would go west and locate in the Rocky Mountains. Mrs. Johnson also gave me her father’s autograph.”[7]

oil painting and the daguerreotype. I chose the latter, and placed it in the hands of the engravers. Before I left, the same spirit led the doctor to say he thought perhaps he would go west and locate in the Rocky Mountains. Mrs. Johnson also gave me her father’s autograph.”[7]

The engraver referred to by Hart was H. B. Hall and Sons, engravers in New York City. The Church had consistently used this business for engraving. Just months before the Three Witnesses image was engraved, Joseph F. Smith had ordered thousands of copies of an engraving of Joseph and Hyrum Smith from this company. Other famous engravings included images of Brigham Young, Willard Richards, the Carthage Jail, the Joseph Smith Sr. family home in Palmyra, the Brigham Young home in Nauvoo, the Heber C. Kimball home in Nauvoo, and many others. H. B. Hall and Sons had established a national reputation for their superior work of engraving: “In the steel-engraving portrait of President Brigham Young, the Artist Proofs of which are now being distributed to subscribers, may be seen an unusual example of perfect steel-engraving. Mr. H. B. Hall, who engraved it, stands at the head of the profession in America, and he has signed the first three hundred impressions from it, declaring that it is the finest work he ever did.”[8]

The engraving of Oliver Cowdery was shown to many people that knew him when he was yet alive, and it was “uniformly pronounced by them to be an excellent portrait.” Although it had been some forty years since any of his contemporaries had seen him, they remarked that “the striking features of his countenance were vividly and accurately preserved.” Wells went on to say in his article that “the only portraits now in existence of Oliver Cowdery are copied from this engraving, as Dr. Johnson’s house was burned and the originals were then lost, soon after Elder Hart was there.”[9] This, however, may not be accurate because the oil painting referred to earlier is probably the one possessed by the Community of Christ Library-Archives.

A niece of Ella Johnson wrote in 1883 concerning the oil painting of Oliver Cowdery owned by the Johnson family.

Oliver Cowdery married Elizabeth Whitmer and she was the daughter of Peter Whitmer brother of John Whitmer. Oliver Cowdery and wife had several children but they all died in infancy but Maria, and she married Dr. Charles Johnson, who was no kin to us. Now Oliver Cowdery and his wife had these portraits in their home at Richmond, MO and Oliver Cowdery’s wife died in 1892 and so her husband hired a housekeeper [Hanna Downs] to stay with him. And Aunt Ella’s mother was there at the time of her death or near then, and they gave her the portraits. So they had been in Aunt Ella’s home until she donated them to the Church [the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, now called the Community of Christ].[10]

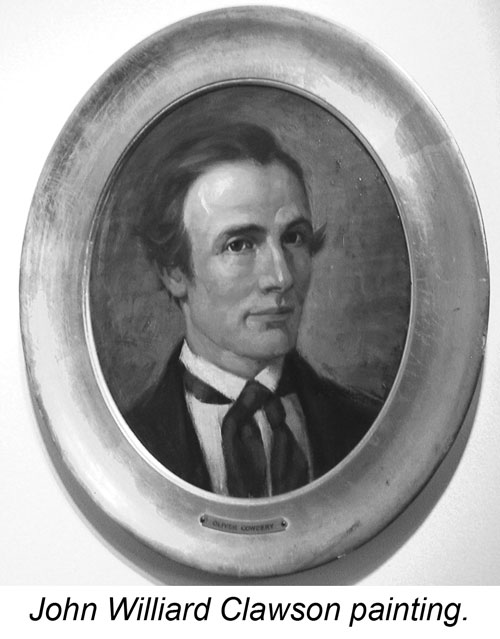

It is therefore believed that this oil painting did survive the house fire. It may be that the original daguerreotype survived also, but it has yet to be discovered. The artist of this portrait has never been discovered. This oil painting is the oldest known image of Oliver Cowdery. It is believed that this painting was done around 1837 when Oliver was about thirty and was part of a series of portraits of Church leaders intended for display in the Kirtland Temple.

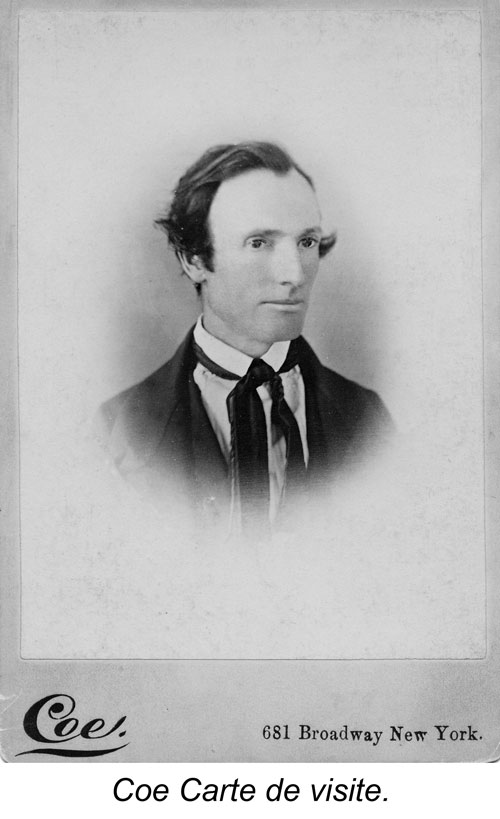

The studio photographer Coe was located on Broadway Street in New York City. No hard evidence has been found for the creation of this image of Oliver Cowdery, although enough surrounding evidence exists to put together a likely scenario. As stated, Elder James H. Hart was the immigration agent for the Church in New York. We have record of Elder Hart taking the original daguerreotype to New York to be copied by Hall and Sons, but no record exists of him having it copied by Coe.

The studio photographer Coe was located on Broadway Street in New York City. No hard evidence has been found for the creation of this image of Oliver Cowdery, although enough surrounding evidence exists to put together a likely scenario. As stated, Elder James H. Hart was the immigration agent for the Church in New York. We have record of Elder Hart taking the original daguerreotype to New York to be copied by Hall and Sons, but no record exists of him having it copied by Coe.

In the biography by Edward Hart, there is a photograph of James H. Hart with some others. The information provided with this image shows that the photographer was Coe of New York in 1884.[11] Therefore, Elder Hart was patronizing this studio at the same time he had the original daguerreotype of Oliver. It therefore seems likely that Hart not only had the image copied by the engravers but also had a photographic reproduction of it made by Coe. This Coe image, therefore, is the closest image to the true likeness of Oliver Cowdery because the original has never been found.

Close study of this image does show some imperfections. The eyes have been doctored to make them appear clearer than they perhaps were in the original. Early daguerreotypes of this nature often have blurs from the subject’s movement during the long time needed to capture the image. This is most easily seen in the hair of the image. This also reduces the natural wrinkles and creases in the face as they are blurred into the rest of the features of the face. Oliver would have been forty-two years old in this picture according to the Johnsons and would have obviously not had this smooth of facial features due to his age and chronic consumption (tuberculosis), which makes the facial tissues appear older. Even so, this image stands as the best likeness of Oliver yet known.

Soon after the steel engraving of Hall and Sons was done, John W. Clawson painted this portrait of Oliver. Concerning this portrait Junius F. Wells said, “[Of] the portraits now in existence of Oliver Cowdery . . . the best of these  copies is an oil painting, made by the artist, Will Clawson. It is hung in the Joseph Smith Memorial Cottage in Vermont. A photograph of the painting may be seen among the historical portraits of the Church Historian’s office.”[12] Clawson was a grandson of Brigham Young called on an “art mission” in the 1890s and studied art in Paris.[13] He is best known for his paintings of President Brigham Young and John Taylor on the current covers of the priesthood and Relief Society manuals of the Church. This portrait of Oliver still hangs in the Joseph Smith birth home in Vermont and was used on the program cover for the Oliver Cowdery Monument dedication in Richmond, Missouri.

copies is an oil painting, made by the artist, Will Clawson. It is hung in the Joseph Smith Memorial Cottage in Vermont. A photograph of the painting may be seen among the historical portraits of the Church Historian’s office.”[12] Clawson was a grandson of Brigham Young called on an “art mission” in the 1890s and studied art in Paris.[13] He is best known for his paintings of President Brigham Young and John Taylor on the current covers of the priesthood and Relief Society manuals of the Church. This portrait of Oliver still hangs in the Joseph Smith birth home in Vermont and was used on the program cover for the Oliver Cowdery Monument dedication in Richmond, Missouri.

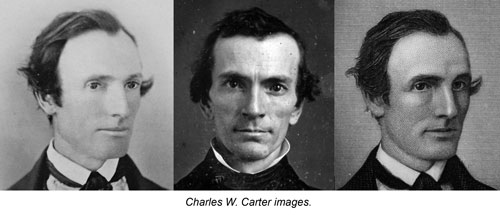

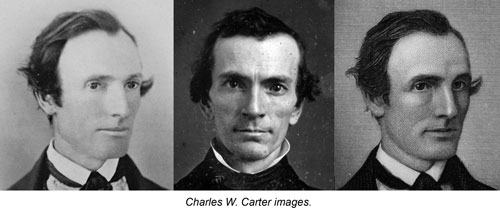

Charles W. Carter was born in London on August 4, 1832, and died in Utah on January 27, 1918. “To him is due the preservation of many scenes in early Utah and on the plains. . . . These photographs have been of great service to historians. . . . He had several studios in Salt Lake at different times, and at one time had a stand outside the temple wall, on the southeast corner of the temple grounds, where he sold his pictures.”[14] Carter also was famous for copying earlier photographs of leading brethren of the Church for a wider distribution of the images to the Latter-day Saint community. Two of his most famous copies were of Joseph Smith Jr. and Brigham Young. Some confusion has resulted from the copying of photographs, however. For example, some have believed that the Carter daguerreotype of Joseph Smith is actually a photo of Joseph Smith while living. This, however, is not the case; the Carter image is a secondhand copy of the Community of Christ oil painting thought to be painted by David Rogers.

To date, we are not absolutely sure what Carter used to take the three images of Oliver Cowdery above. Two are carte de visite images, one held by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in their archives, and the other by the Community of Christ Library. The middle image is part of the glass-plate negative collection sold to the Latter-day Saint Church by Carter in 1906.[15] All of Carter’s photographic journals have been researched to discover the source of his images. No entries have been found giving the original source photographed. There also is no evidence that Carter ever came in contact with the Johnson family to copy the original daguerreotype. I believe the Carter images are copies of the Coe image reproduced by Elder Hart while in New York City. Carter may have slightly retouched the images, especially the eyes, where there are many flaws in the Coe image. Therefore, the images of Oliver by Carter are probably third-generation images.

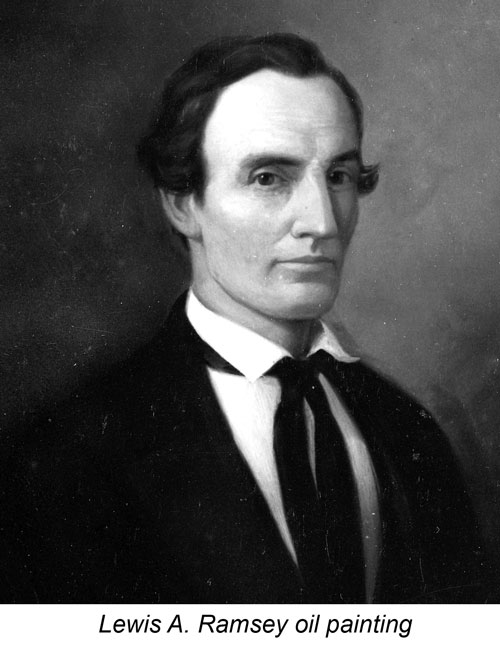

So impressive was the work of Lewis A. Ramsey that fourteen of his works were hanging in the Salt Lake Temple at the time of his passing in 1941. Ramsey was commissioned by the Church to paint the Three Witnesses based on the earlier engraving done for the Contributor in 1883. The work was completed in 1911 and is owned by the Church History Museum. It currently hangs in the hallway of the fourth floor of the Salt Lake Temple.

So impressive was the work of Lewis A. Ramsey that fourteen of his works were hanging in the Salt Lake Temple at the time of his passing in 1941. Ramsey was commissioned by the Church to paint the Three Witnesses based on the earlier engraving done for the Contributor in 1883. The work was completed in 1911 and is owned by the Church History Museum. It currently hangs in the hallway of the fourth floor of the Salt Lake Temple.

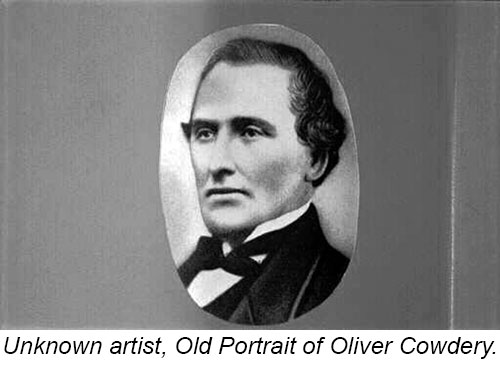

This engraving titled Old Portrait of Oliver Cowdery is held in the Church History Library in Salt Lake City. There is no recorded history as to who produced the engraving or when it was done with this image. It is believed to be a work of the nineteenth century.

the nineteenth century.

A full article could be written on the accomplishments in art of Avard T. Fairbanks. Perhaps his best known work is the bronze work of the pioneer parents looking down on their baby being put into a grave. The monument is located at the Winter Quarters Cemetery in Florence, Nebraska. President Heber J. Grant said of this sculpture, “I do not believe there is a more beautiful or finer monument to be found in all the United States than that monument by Brother Avard Fairbanks. I believe it is his masterpiece, and that it will give him a reputation with everybody who sees it. The sorrow depicted on the face of the mother as she looks down into the grave of her babe is perfectly wonderful.”[16] Avard’s bronze casting of Oliver is modeled after the other orginal images of Oliver. This casting of Oliver Cowdery with the other witnesses of the Book of Mormon is placed on a granite monument just south of the Church Office building as a standing tribute to the Three Witnesses.

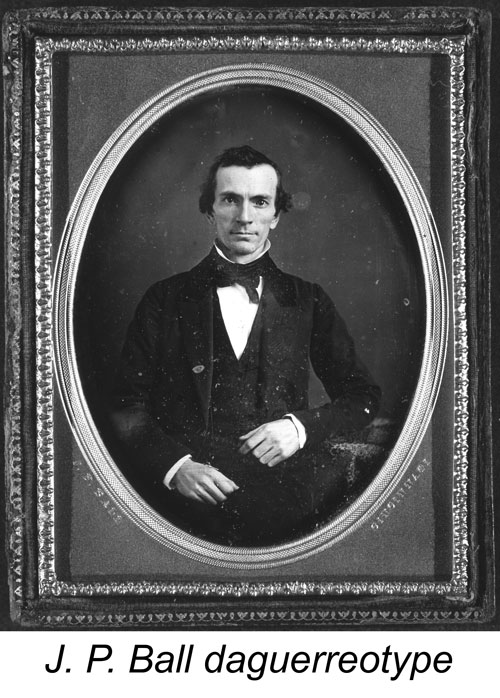

In February 2006 this image was brought to light as a possible newly discovered image of Oliver Cowdery. The original article attempting to authenticate the image was published that same year in BYU Studies.[17] Several criteria were used to substantiate the image. These included showing the daguerreotypist and Oliver were in the same region of the country at the same time, dating the clothing and the age of the subject, identifying his face using other known images of Oliver, and using a physical description. Only a brief discussion will be presented here as the original article can be reviewed for more details. Some additional research has been done since the article in BYU Studies was published and will be addressed also.

In February 2006 this image was brought to light as a possible newly discovered image of Oliver Cowdery. The original article attempting to authenticate the image was published that same year in BYU Studies.[17] Several criteria were used to substantiate the image. These included showing the daguerreotypist and Oliver were in the same region of the country at the same time, dating the clothing and the age of the subject, identifying his face using other known images of Oliver, and using a physical description. Only a brief discussion will be presented here as the original article can be reviewed for more details. Some additional research has been done since the article in BYU Studies was published and will be addressed also.

J. P. Ball was one of the first black daguerreotypists in the United States of America. He first opened a studio in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1845, but he closed his doors for a time to make a better living and headed back East. After a year, Ball began to travel throughout Ohio and again was employed as an itinerate photographer. Then in 1847 he again established a permanent business in Cincinnati.[18] During the years that Ball was taking daguerreotypes, Oliver Cowdery was living in the same region, Tiffin, Ohio. If the image is of Oliver, it is probable that Ball took the daguerreotype while traveling the state of Ohio. Kristin Spangenberg, a curator of prints, drawings, and photographs of the Cincinnati Art Museum, has stated that Tiffin would have been a major stopping point during Ball’s 1846 touring.

Some have had the impression that this image could not be a new image of Oliver because it was not found among family descendants and because of its lack of provenance. As stated, Oliver’s immediate family and the Whitmers said that the daguerreotype that Elder Hart had copied was the only one that they knew of to be in existence. Therefore, some have taken this to mean there was never another taken, but this has never proven to be absolute. There could be other daguerreotypes of Oliver in existence through other family lines, such as Oliver’s brothers, one of which he lived with in Wisconsin immediately after he left Ohio. Historical mementos have also often been found among cousins and in-laws. A broader search could be conducted among these types of descendants to see if another copy exists.

It should also be noted that early photographers often sought out prominent people to advertise their work. Lucian Foster, a daguerreotypist in Nauvoo, ran an advertisement in the local paper which stated, “How valuable or rather invaluable, would be such a likeness of an absent or departed friend. Specimens may be seen . . . at the Nauvoo Mansion.”[19] It is obvious from this statement Foster had examples of his work. Some believe a daguerreotype of Joseph Smith was among them. Oliver would have been a prime candidate for this type of work also. He was a very public figure in Ohio at the time with his law practice and his political ventures. His history followed him also as one of the Three Witnesses and the Second Elder of the Church. It is very possible that this daguerreotype was taken and used by Ball as advertisement and never found its way into the Cowdery, Johnson, or Whitmer families.

Carma de Jong Anderson has done a complete examination of the clothing and concurs that the clothing is authentic to the mid-1840s, the type Oliver would have worn during these years. The Museum of Cincinnati curators of fashion also sustain these findings.

Previously published was a facial comparison of the Ball image to the engraving of Oliver. Below is a reproduction of this with the Coe image added because it is the closest image to the original daguerreotype.

After the initial publication of this alleged image of Cowdery, two separate and independent forensic specialists were sought out to analyze the image in comparison with other known images of Oliver. Covert Sciences of South Carolina and Advanced Biometrics of Vancouver, British Columbia have each preformed in-depth analyses on this newly discovered image. Each scientific study has ratified the original idea that this new image is indeed that of Oliver Cowdery.

Covert Sciences’ conclusion was, “I believe that the features in the ‘unidentified’ photo are highly consistent with known images of Cowdery to the probable exclusion of coincidence.”[20] This conclusion was based on the overall facial features and an analysis of the ears on each image. Advanced Biometrics’s final analysis was, “It is the opinion of Advanced Biometrics . . . that it is highly likely that the images taken by Coe [Elder Hart’s copy of Oliver] are of the Unidentified Man [J. P. Ball daguerreotype].” This conclusion was reached after running the unidentified image against a test database of 7,000 random faces that included the known images of Oliver Cowdery. Out of these 7,000 random faces the image with the closest facial structure to Oliver Cowdery was the J. P. Ball daguerreotype.[21]

Another medical study was also conducted, and even more information came to light. Upon examining the daguerreotype, John W. Pickrell, M.D., of the Casper, Wyoming, Medical Center, noticed “that the temporal wasting and gaunt cheeks in this image are characteristic of chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis or consumption.”[22] It is well documented that Oliver Cowdery did have this type of illness the last several years of his life. In a letter to his brother-in-law, Phineas Young, Oliver wrote:

Sometime in August I had an attack of bilious fever; the most severe of any in my life, but with the blessing of heaven, and the kind care of friends, I recovered in a few days. Unfortunately for me, before recovering sufficient strength, I rode out when the weather was very warm, which brought on a severe attack of chills, together with a return of my old difficulty of lungs. The chills were soon disposed of, but my lungs are very bad, with considerable cough. I have been careful to take exercise in the open air and flatter myself that my cough is less severe and that I raise less also. I have spit no blood during this attack as last winter; a circumstance also favorable, as I interpret it. I am thus particular—all of which is strictly time—that you may know how much I desire an interest in your prayers.[23]

Cowdery’s chronic lung condition advanced to tuberculosis, and on March 3, 1850, he died while at the home of his in-laws, Peter Sr., and Mary Musselman Whitmer.[24]

Many historians have also joined in the effort to determine if the image is that of Oliver. They have helped clarify many historical issues concerning Oliver’s life. All of the research thus far is circumstantial and does not prove absolutely that the person in the image is Oliver. Yet there has not been any evidence pointing to the contrary, and the image has been generally accepted as a genuine image of Oliver Cowdery.

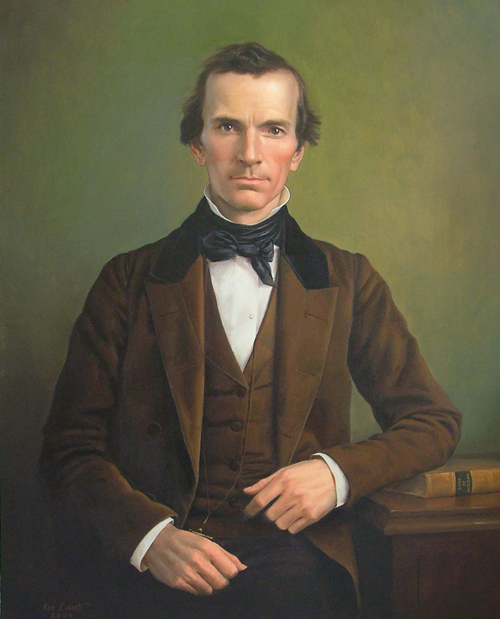

In August 2006, the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation commissioned Ken Corbett to paint a new portrait of Oliver Cowdery for his bicentennial celebration based on the newly discovered J. P. Ball daguerreotype. Ken’s painting is masterfully done. The only change made from the original daguerreotype is the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon under his elbow. This is a symbol of Oliver’s never denying his testimony of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

Ken Corbett oil painting.

In 2006 three celebrations were held for the bicentennial of Oliver’s birth. The first was held in September in Wells, Vermont, the birthplace of Oliver Cowdery. During that commemoration a copy of Corbett’s portrait was given to the town of Wells and now hangs in the town hall. The second was held in Richmond, Missouri, on October 6, the community where Oliver passed away. Here, a second Corbett painting of Oliver was presented to the mayor on October 6, 2006, and this copy hangs in the Ray County Court House. Finally, on November 10, a symposium on Oliver Cowdery’s life was held at Brigham Young University where the original Corbett oil painting was unveiled. Corbett’s original has since been donated to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Conclusion

One hundred twenty-three years have passed since Joseph F. Smith wrote, “It is simply out of the pure love for Oliver, and an earnest desire to perpetuate his remembrance that I desire to obtain his likenesses.”[25] It is truly amazing to see a prophet of the Lord’s desires come to pass. Many wonderful images of Oliver Cowdery have been produced over the years for all of us to remember what a marvelous work Oliver Cowdery performed during his lifetime.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, January 31, 1883, Joseph F. Smith Letterpress Copybooks (1875–1917), Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, March 29, 1883, Church History Library.

[3] Junius F. Wells, “The Three Witnesses,” Contributor, October 1883, 34.

[4] Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, April 24, 1883, Church History Library.

[5] Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, July 3, 1883, Church History Library; see also Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. Van Cleave, May 21, 1873, Church History Library.

[6] Edward L. Hart, Mormon in Motion: The Life and Journals of James H. Hart, 1825–1906, in England, France and America (n.p.: Windsor Books, 1978), 211.

[7] James H. Hart to Junius F. Wells; cited in Junius F. Wells, “The Engraving of the Three Witnesses,” Improvement Era, September 1927, 1023.

[8] “Steel Engraving,” Contributor 10, no. 3 (January 1889): 117.

[9] Wells, “The Engraving of the Three Witnesses,” 1024.

[10] Letter from a niece of Ella Johnson, (Kingston, Missouri) to C. Edward Miller, May 26, 1932. Community of Christ Library-Archives, Independence, Missouri.

[11] Hart, Mormon in Motion, 241.

[12] Wells, “The Engraving of the Three Witnesses,” 1024.

[13] Richard G. Oman, “Artists, Visual,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 1:71.

[14] Improvement Era, March 1918, 465.

[15] Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and R. Q. Shupe, Brigham Young: Images of a Mormon Prophet (Salt Lake City: Eagle Gate, 2000), 199.

[16] Heber J. Grant, in Conference Reports, October 1936, 12.

[17] Patrick A. Bishop, “An Original Daguerreotype of Oliver Cowdery Identified,” BYU Studies 45, no. 2 (2006): 100–111.

[18] See Deborah Willis, J. P. Ball Daguerrean and Studio Photographer (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1993).

[19] “Miniature Likenesses,” Nauvoo Neighbor, August 14, 1844.

[20] Jeff Spivack to Patrick A. Bishop, August 31, 2006. Spivack is a certified forensic consultant (ACFEI, EPIC, SMPTE) with Covert Sciences, 334 East Bay Street, #235 Charleston, South Carolina, 29401.

[21] Advanced Biometrics Inc. to Patrick A. Bishop and the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation, March 30, 2008. Special thanks to the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation for funding this biometric analysis. Copy of report held by Patrick A. Bishop and the Mormon Historic Sites Foundation.

[22] John Pickrell to Patrick A. Bishop, August 8, 2001.

[23] Oliver Cowdery to Phineas Young, June 24, 1849, from Richmond, Missouri; cited in Stanley R. Gunn, Oliver Cowdery (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1962), 207.

[24] LaMar C. Berrett and Max H. Parkin, Sacred Places, vol. 4, Missouri: A Comprehensive Guide to Early LDS Historical Sites (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 258.

[25] Joseph F. Smith to James R. B. VanCleave, January 31, 1883.