The 1911 Dedication of the Oliver Cowdery Monument in Richmond, Missouri

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Robert F. Schwartz, “The 1911 Dedication of the Oliver Cowdery Monument in Richmond, Missouri,” in Days Never to Be Forgotten: Oliver Cowdery, ed. Alexander L. Baugh (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 339–84.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel was a professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University, and Robert F. Schwartz was an attorney when this was published.

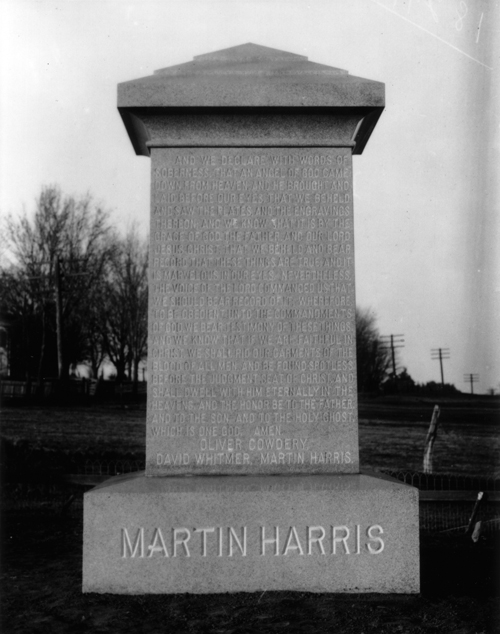

As one of the Three Witnesses, Oliver Cowdery claimed that “an angel of God came down from heaven” to display an ancient record, a record known as the Book of Mormon. Cowdery, Martin Harris, and David Whitmer affirmed in written testimony that they saw “the engravings thereon” and that the voice of God declared Joseph Smith’s translation of the record to be true.[1] Even though all three men eventually disassociated themselves from Joseph Smith, they never denied their witness, and later members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints commemorated Cowdery, Whitmer, and Harris for their role in the Church’s genesis. In 1911, Church member Junius F. Wells erected a monument in Richmond, Ray County, Missouri, toward this end[2] (figs. 1, 2).

David Whitmer's home, November 21, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

David Whitmer's home, November 21, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Wells wrote an account of his efforts to erect the monument, which he published in January 1912.[3] His article focuses on interviews that he conducted in Richmond with the nearest of kin of Cowdery and descendants of Whitmer, as well as on his efforts to gain both their trust and the trust of Richmond’s citizens. The present paper covers some of the same ground that Wells did in his original article; however, the scope of this article is broader. Using primary source data from Wells’s personal papers held in trust by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the authors intend to recapture and add to the story of the labors of both Wells and the Church to erect a monument in memory of the Three Witnesses, Oliver Cowdery in particular. The authors will also include photographs taken by pioneering photographer George Edward Anderson that capture many events involved in creating and dedicating the monument. The article provides remarkable views of a cooperative effort between local Missourians and Mormons in an area where only seventy years earlier the two parties were at war with one another.

A Promise to Commemorate Oliver Cowdery

Church members had longed to return to Missouri since their earlier expulsion in 1833. After attending the annual Trans-Mississippi Commercial Congress in San Antonio, Texas, President John Henry Smith, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, traveled to Independence, Jackson County, Missouri, in 1910. The Church had only recently reestablished a presence in Independence. President Smith, along with former and presently serving mission presidents Samuel O. Bennion, John L. Herrick, and Joseph A. McRae, visited nearby historical sites.[4] On November 30, 1910, the party visited Richmond, located thirty miles northeast of Independence in Ray County.

Like Independence, Richmond has a past rich in Latter-day Saint history. Joseph Smith and other Latter-day Saint Church leaders were imprisoned in a makeshift Richmond jail during a preliminary hearing held against them in November 1838. Later, after the Mormons were driven from Missouri in 1838–39, the Richmond area became home to several former leaders of the Church who no longer accepted Joseph Smith’s leadership. This group included David Whitmer, Jacob C. Whitmer, Hiram Page, and Oliver Cowdery, each of whom played key roles in the Church’s founding events. Cowdery and his wife, Elizabeth Whitmer,[5] moved to Richmond in 1849 shortly before he passed away. Cowdery was estranged from Joseph Smith by 1838 and was excommunicated from the Church in Far West. Before his death in 1850, however, Cowdery rejoined the Church and planned to gather with its members in Utah. Maria Louise Cowdery (1835–92), the daughter of Oliver and Elizabeth Cowdery and the only Cowdery child who lived to maturity, married Dr. Charles Johnson and died without any living descendants in Southwest City, Missouri, in 1892.[6]

Old city cemetary, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri, November 21, 1911.

Old city cemetary, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri, November 21, 1911.

While in Richmond, John Henry Smith and his party visited local cemeteries, trying to locate the graves of Cowdery, Page, and David Whitmer.[7] President Smith wrote, “We went to the old grave yard to visit the grave of Oliver Cowdery and Hyrum Page but we could not locate them but were told they were in the north end of the Cemetery.”[8] President Smith was obviously not aware that Hiram Page was not buried in Richmond and that David Whitmer was buried in a different Richmond cemetery. President Smith and his company apparently came into contact with George W. Schweich, Cowdery’s nearest living relative in the Richmond area. (Schweich’s mother, Julia Ann, was the daughter of David Whitmer, Cowdery’s brother-in-law.) President Smith promised Schweich that the Church would erect a monument in Cowdery’s memory.[9] Schweich and A. K. Raeburn—a ninety-three-year-old former sheriff who claimed to be present when Cowdery was buried in March 1850—helped President Smith identify Cowdery’s final resting place.[10]

When President Smith returned to Salt Lake City, he approached Junius F. Wells about the possibility of erecting a monument in Richmond. Wells had already successfully purchased, on behalf of the Church, Joseph Smith’s birthplace in Sharon, Vermont, and had erected there a large granite monument in Smith’s honor in 1905 (fig. 3).[11] In fact, Wells had already given thought to erecting a monument in Cowdery’s honor when Smith approached him. He afterward wrote, “I had a very clear notion of the kind of monument and suitable inscriptions thereon.”[12] He also planned to erect additional monuments at the grave sites of David Whitmer and Martin Harris.[13]

The decision to build a monument to Joseph Smith in 1905 and to Cowdery in 1911 reflects broader national trends in monument building that took hold after the Civil War. Historian David Lowenthal comments, “The Civil War may have freed Americans from the burden of filial piety, but in its wake came a wave of nostalgia for other periods or aspects of the American past.”[14] Michael Kammen says of this nostalgia, “The importance of ancestors, memories, and legends . . . predominate[d] . . . American art of the period [from 1870 to 1915].”[15] Many historians agree that the period following the Civil War, stretching into the early years of the twentieth century, marked a watershed in American monument building. Key monuments include Abraham Lincoln’s tomb in Springfield, Illinois (completed in 1874), a monument to Stonewall Jackson in Richmond, Virginia (1875), and a monument to Robert E. Lee, also in Richmond (1890). In the 1890s, the federal government acquired Civil War battlefields—Gettysburg being the most prominent. During this period, a multitude of local monuments sprang up on town squares, at civil War and other sites, and in cemeteries throughout the country, including the monument to Cowdery in Richmond, Missouri.[16]

After personal reflection and planning, Wells decided on a text that would honor not only Oliver Cowdery but Joseph Smith and all three witnesses, even though he hoped to erect separate monuments to Harris and Whitmer later. He submitted his proposal for the monument, including inscriptions and cost estimations, to the First Presidency, (President Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, and John Henry Smith). Wells reported, “This was approved by the First Presidency and Twelve, and I was commissioned to carry it out.”[17]

Preparing a Monument

Wells immediately set about working to build Oliver Cowdery’s monument. He contacted R. C. Bowers, president of R. C. Bowers Granite Company in Montpelier, Vermont, sometime before the middle of February. Bowers was the general contractor who organized the logistical efforts involved in constructing the 1905 Vermont monument. In contracting Bowers, Wells was freed from worrying about the details involved in monument construction, such as quarrying, polishing, inscribing, and transporting.[18]

On February 13, 1911, Bowers responded to Wells’s inquiry: “Referring to your favor of recent date in regard to design of the monuments, the monument[s] alone would be worth $900.00 each F. O. B. cars here, and would weigh about 36000 lbs. each. The V sunk inscription letters would be worth 18 cents each. If the continuous inscription of 1264 letters is smaller letters, they would be worth from 12 to 15 cents each.”[19] Wells promptly approved the bid on February 20.

In March, Wells queried Bowers regarding the progress of the work: “In looking at my file I find that it was on February 20th that I wrote you last asking for the perspective drawing of the design of the three monuments and enclosing in my letter a printed slip containing the inscription. I also enclosed my check for $30.00.” He closed his letter, perhaps somewhat questioningly, “Trusting that you are well and that everything is flourishing.”[20] Five days later, Bowers responded: “Your favor of the 25th inst. is at hand and . . . [t]he check was received and the letter put with some other correspondence to be answered later, but in some way or other it was overlooked. I am very sorry to have been negligent in this matter and will attend to it at once.”[21]

Within a week, Wells received the update from Vermont: “Just got word from the man that makes our designs that he has been sick but he will get right at your design and lose no time in finishing it. Sorry to have delayed you and hope to send it to you shortly.”[22] On April 19, Bowers sent by “express this morning” the examples of the design.[23]

On May 19, 1911, Wells, still in Salt Lake City, formalized his obligations regarding the monument’s erection when he signed an agreement with President Joseph F. Smith, promising “to procure the requisite consent of the parties lawfully interested and secure the site in the cemetery at or near the burial place of Oliver Cowdery, to erect thereon a monument of dark barre granite accord to the design and inscription submitted.” Presidents John Henry Smith and Anthon H. Lund also signed the document as witnesses.[24]

Soon thereafter, Wells traveled to Richmond for the first time.[25] Wells indicated that he hoped to accomplish several important objectives during this visit: first, visit the cemetery; second, identify Cowdery’s grave; third, obtain the consent of the local officials to erect a monument; fourth, obtain approval from the nearest of kin living there; fifth, select a site for the monument; and finally, secure the goodwill of the people of Richmond.

Obtaining the goodwill of the people was not necessarily as easy as it might appear to the modern reader. Controversy surrounding polygamy generated ill will toward the Church’s members through the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth. Although the practice of polygamy had officially ended in 1890, controversy and misunderstanding continued. The situation came to a head in the early years of the twentieth century when Elder Reed Smoot was elected to the U.S. Senate. Public senatorial hearings regarding his suitability for office ensued, and newspapers nationwide criticized Utah.[26] The years 1910 and 1911 witnessed a significant recurrence of anti-Mormon feeling throughout the country due to negative fallout generated by Smoot’s reelection. It might, indeed, be assumed that the monuments of 1905 and 1911 were constructed partly in the hope of engendering goodwill for the Church.

Contrary to what he might have expected in the political climate, Wells was pleasantly surprised by the welcome he received from the hospitable people of Richmond. He received solid support from George W. Schweich, who emphasized his willingness to help and expressed his feelings about erecting another monument in Richmond to honor his grandfather David Whitmer.[27]

Wells went to the Old City Cemetery, known today as the Pioneer Cemetery (fig. 4).[28] He described his visit:

Out to the northward, on the state road and near the boundary of the city—long before Richmond became a city—an acre of ground was selected and bought by the people—the deed dated August 14, 1846, running from John C. Richardson to three trustees, to be held by them: ‘In trust for the sole and exclusive use and benefit of the inhabitants of the Town of Richmond, as a public burying ground forever.’ Among the earliest graves within this sacred acre are those of Father Peter Whitmer’s family and kindred, whose burying lots appear to have occupied about sixteen by sixty feet, along the east side of a central drive, entering at the north end of the cemetery. Within this boundary, and in the southern part, are buried the bodies of Peter Whitmer, and his wife, Mary Musselman Whitmer—father and mother of the Witnesses,—Jacob Whitmer, one of the Eight, and two more of his daughters, and other members of his family. I counted thirteen graves, most of them unmarked, except by crude stones without inscriptions.[29]

After making initial contacts in Richmond, Wells made his way to Vermont to select the stone for the monument. While stopping in New York, Wells received a letter from George W. Schweich dated May 27, 1911. Schweich reemphasized his willingness to help and his feelings about erecting another monument to honor David Whitmer. Schweich wrote: “Regarding the monuments spoken of by you especially on Oliver Cowdery’s grave that certainly I have and will assist the people you represent to erect the monument over so noble a man, and whose life is so dear in my memory as to merit all you feel to do. At the same time—I wish you not to forget that coincident with his work there lays another of your honored dead . . . who was a brother to Oliver and who worked labored and plead in the same cause that you showed not forget in bestowing such honors.”[30] Schweich added, “You will remember that after visiting both graves and telling of our visit to Mayor Powell how generous he was to concede my requests which were yours as well; to occupy the ground to make excavations and grades—subject to only one restriction that the city engineer would see that street grades were not out of alignment—I must reiterate there is not a bit of personal or selfish pride or reward in my motive but a broad view candid and clean.”[31] Although Wells hoped that Whitmer could be honored at some future time, he set his sights on erecting the Oliver Cowdery monument as soon as possible.[32]

In early June, President John Henry Smith left Salt Lake with members of the Utah Capitol commission to visit state government buildings in order to get ideas for the proposed Utah Capitol.[33] While in Maine, President Smith noted, “I met Junius F. Wells and we decided to leave the party and Visit Kindred in New Hampshire, Vermont and Northern New York states.”[34] On June 12, Smith and Wells met up with Ben E. Rich and “a Mr. Milne and Mayor Boutwell of Montpelier, Vermont who took us in his Auto to the Joseph Smith Monument where Bro. Brown gave lunch. We planted 6 trees. We called at the Barre Marble Quarries.”[35] Apparently, they “selected the stone, and the order was given for the manufacture of the [Cowdery] monument” on this occasion.[36]

Within a few days, R. C. Bowers sent Wells an envelope containing a letter of introduction to M. H. Rice of the Woodland Monument Company in Kansas City, Missouri, asking Rice to assist Wells in his effort to erect the monument.[37] Specifically, Bowers informed Rice that the project would “require teams, derrick and experienced men in setting work, to assist him.”[38] In the end, this contact did not work out, and Wells chose another company closer to the project in Richmond itself.

During the first week of August 1911, Bowers contacted Wells, who was staying in South Royalton, Vermont. He wrote, “We have your monument all ready to letter and have the lettering drawn up for it, and would be pleased to have you come up at once and look the lettering over as we wish to start lettering it Monday.”[39] Due to a misunderstanding, Wells failed to contact Bowers to approve the lettering, causing additional delay.

Days later, while on another visit to Richmond, Wells met with several of Cowdery’s family members, including Philander A. Page, Julia Ann Schweich, and George W. Schweich, in an effort to obtain their legal consent to erect the monument.[40] Each said they would not oppose Wells’s efforts. Page said he “preferred not to sign his approval, as he was not in favor of so much display.”[41] The Schweich family members, on the other hand, were not only supportive but also helped in every way to assist Wells. Regarding Julia Ann Schweich, daughter of David Whitmer, Wells stated, “She was seventy-six years old in September, and is a very smart, clear-minded lady of remarkable memory, firm convictions, honest, outspoken, and independent. I became much attached to her, and enjoyed repeated interviews with her, in which she told me many things concerning her father, his family and the family connections.”[42]

On August 8, Wells obtained the legal consent of Cowdery’s relatives to proceed with the project. The document states that Cowdery’s relatives “approve of this undertaking and freely consent to it and thereby authorize Junius F. Wells acting for himself, ourselves and fellow believers in the above testimony [testimony of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon], to take every necessary step to locate the site of said grave and erect said monument thereon only hold the undersigned free from expense connected therewith.”[43]

Still concerned that Oliver Cowdery’s grave site had not been correctly identified, Wells visited the graveyard on August 9 with A. K. Raeburn. Wells did this again on August 18 and on November 23 to gain complete assurance that Raeburn provided the same description.

After repeatedly hearing Raeburn’s description, Wells went to the cemetery to carefully review what he had been told. He wrote:

“I found by measuring the distance between the graves, and between the headstones and footstones, that there were two graves, shorter than the grave of a full grown man, north of the depression which was supposed to be the grave of Oliver Cowdery. By some digging, we found the rotting stones that had supported the headstone, which was gone, and six and half feet eastward, a large, though crumbling, footstone. This supplied whatever assurance was lacking as to the identify of the grave we sought—especially as the next grave, seven feet southward, was that of a child.”[44]

With written permission of Cowdery’s surviving family now in his possession, Wells met with the mayor of Richmond and some of the city councilmen and “arranged with the city engineer to establish the grade of the street—Crispin avenue—on the north line of the cemetery—and to stake out and set the levels of the foundation of the site selected for the monument.”[45] The city engineer, W. A. Mullins, billed Wells three dollars for survey work and setting the corners.[46]

Once the preliminary work had been completed, Wells presented the following petition to the mayor and council during their meeting on August 15, 1911:

The late Oliver Cowdery, intimate associate and relative of the late David Whitmer your long respected fellow townsman, was a resident of Richmond, Mo., for about a year prior to his death.

He died here on the third of March, 1850, and his body is buried in the Old City Cemetery or Public Burying ground, near the middle of the northern boundary thereof, his grave unmarked.

The undersigned has been authorized by his nearest kin, living, and by his fellow-believers of the so called Mormon faith, of which he was one of the founders, to erect at his grave a commemorative monument in his honor. It will be of polished granite six feet base, and about ten feet high.

Upon looking over the ground, it is found that the most suitable site for this, near the head of his grave, will necessarily occupy a portion of what appears to have been the end of a driveway. As this drive has long since ceased to be used, if it ever were and probably never will be used again, permission is respectfully requested to establish the foundation and to build the proposed monument at this location, as provisionally staked out by the City Engineer.

And your petitioner, as in duty bound, will ever pray.[47]

After some discussion by the mayor and city council, the clerk noted, “Therefore be it resolved by the Council of the City of Richmond, that permission be granted to the said Junius F. Wells to erect said monument at the point as staked out by the City Engineer, W.A. Mullin.” The city’s final approval was granted on August 16, 1911.[48]

Once approved by the city council, preparations at the site itself continued as J. W. Hagans graded the spot for the monument and prepared a six-foot-square concrete foundation at a cost of $67.50.[49] On October 26, 1911, Wells and Schweich placed a metal box in the foundation, a time capsule that contained a number of books, periodicals, pictures, and miscellaneous items.[50]

While efforts in Richmond to erect the monument proceeded, work on the monument itself ceased for a few weeks when unusually hot weather in Vermont “shut down work in the stonecutter’s sheds.”[51] Since Wells had failed to authorize the lettering of the monument, Bowers wrote: “I am in receipt of your favor of the 18th inst. and regret to say we were delayed two weeks on your monument on account of the lettering not being approved, as I did not feel safe in starting it until I heard from you. The lettering is all that will hold us up now and I assure you that we will do the very best we can in rushing the work out.”[52]

Originally, Wells and President John Henry Smith desired to dedicate the monument on October 3, 1911, the anniversary of Oliver Cowdery’s birth.[53] However, due to these delays, they set back the date for the dedication.

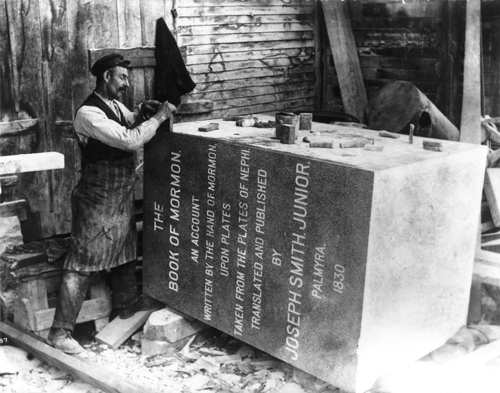

A few weeks later, Utah portrait and landscape photographer George Edward Anderson visited the workshops at Barre, Washington County, Vermont. In his first photograph related to the erection of the Oliver Cowdery monument, Anderson captured in black and white a craftsman engaged in his work on the monument (fig. 5).[54]

Oliver Cowdery Monument, October 10, 1911, Barre, Washington County, Vermont. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, October 10, 1911, Barre, Washington County, Vermont. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

A Change of Plans

President John Henry Smith had been busy during the first half of 1911 fulfilling Church, business, and governmental responsibilities. Few knew that his health was failing rapidly. President Smith passed away on October 13, 1911. Wells revealed, “The lamentable death of Elder Smith occurring on the thirteenth [October], caused a complete change in the plans respecting the dedication.”[55] Wells decided to work for a date later in the year to coincide with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir’s six-thousand-mile national tour, which began on October 23, 1911. Wells hoped to arrange for the choir to stop briefly at Richmond on its return trip to Salt Lake City, following a scheduled concert in Kansas City on November 21 and before another scheduled concert in Topeka on November 22. While the choir’s tour was generally considered a success, especially in light of the anti-Mormon mood that prevailed nationwide, the choir encountered stiff opposition in various places. In some cases, they could not secure places to perform and, in the end, incurred a deficit of some $20,000. In the face of the budgetary concerns that surfaced during the tour, Wells needed to demonstrate that a side trip to a small Missouri town would not push the choir further into the red and that they would be received warmly by the local people.

Getting Everything in Place

Assuring that work on the monument was moving forward also consumed Wells’s efforts. Anxious to move ahead, he wrote to Bowers on October 10 (the day Anderson took the photograph in the shed at Barre): “Expected notice of shipment, before now. Please advise cause of delay. If ready box and ship to me as already advised and start transfer. Shall be there to meet it. Send statement to Richmond. Intend to go from there to Vermont to settle with you.”[56] Unbeknownst to Wells, Bowers had written and mailed a notice that same day, stating, “Monument will leave here tomorrow.”[57] Once Wells received the notification, he contracted with Thomas B. Blount, a house-moving company in Richmond, to transport the monument from the railway station to the cemetery. Wells wrote to Blount, “Accept your offer. Please be ready to receive monument shipped from Montpelier eleventh. I shall be there by twentieth. Make sure that every rope, chain, pulley, and anchor are sound and strong. I may bring men to assist in erection but do not depend on that. Be prepared.”[58] The men “had quite a time hauling it on the house-moving trucks and setting it, but finally got it up without accident”[59] (fig. 6). The monument was in place in the Old City Cemetery by November 1, 1911 (fig. 7). The total expense for transporting and setting the monument was one hundred dollars.[60]

Transporting the Oliver Cowdery Monument to the cemetery from the railway ca. November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Transporting the Oliver Cowdery Monument to the cemetery from the railway ca. November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Wells still had not yet secured the commitment for the two-hundred-member Mormon Tabernacle Choir to participate in the services. They were already in New York when Wells appealed to George D. Pyper, the choir’s tour manager, trying to persuade him to make the necessary arrangements for the proposed stop:

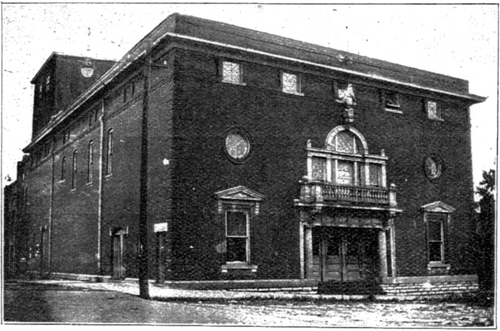

“Upon arriving here, I found that they have a very nice little opera house practically new and clean and well furnished, there are actually six hundred orchestra chairs, and other seats for a least four hundred with the boxes and standing up twelve hundred people can be admitted. The people here are sufficiently interested in having you come that they have assured me if I find that you can do so, they will tender us the free use of the opera house, warmed and lighted.”[61]

After providing several more issues for Pyper’s consideration—including further description of available facilities and necessary costs—Wells concluded, “I sincerely hope that nothing will occur to prevent carrying out this program. It will be very delightful for everybody and will do a lot of good.”[62]

Transporting the Oliver Cowdery Monument to the cemetery from the railway ca. November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Transporting the Oliver Cowdery Monument to the cemetery from the railway ca. November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. This view shows the monument just after it was placed on the concrete foundation before the ground around the monument was graded. Wells provided a descriptions: "the Monument is of dark Barre granite, resting on a concrete submerged base, six feet square. It is composed of three pieces, all polished; rises to a height of eleven feet, and weighs eighteen tons." See Junius F. Wells, "The Oliver Cowdery Monument," Improvement Era, January 1912, 266. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 1, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. This view shows the monument just after it was placed on the concrete foundation before the ground around the monument was graded. Wells provided a descriptions: "the Monument is of dark Barre granite, resting on a concrete submerged base, six feet square. It is composed of three pieces, all polished; rises to a height of eleven feet, and weighs eighteen tons." See Junius F. Wells, "The Oliver Cowdery Monument," Improvement Era, January 1912, 266. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 20, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On this side and the other is found "The Testimony of the Three Witnesses" as printed in the Book of Mormon itself. The text begins on the David Whitmer side, continuing on and concluding on the Martin Harris side. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 20, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On this side and the other is found "The Testimony of the Three Witnesses" as printed in the Book of Mormon itself. The text begins on the David Whitmer side, continuing on and concluding on the Martin Harris side. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Within a mere week of sending Pyper the letter, Wells received a letter from President Joseph F. Smith, dated November 2, informing him that he could not “arrange choirs proposed visits to Richmond.”[63] President Smith informed Wells that he would have to get in contact with Evan Stephens, the director of the choir. He added, “Whatever he agrees to do will be satisfactory to us if choir cannot attend arrange with Bennion for simple services.”

Eventually, choir leaders agreed that the choir would perform at the dedication, and Wells began the Herculean task of arranging for the visit of so large a party to Richmond. Additionally, some fifty people, most of them family of the choir members, accompanied the choir on their tour. Their presence brought the total number of Latter-day Saints present on this occasion to about two hundred fifty. Wells wrote the owner of the local hotel in Richmond: “Dedication service Wednesday morning, twenty-second, ten o’clock sharp. Choir must have breakfast and be seated in Topeka House by nine forty-five. Dinner must be all ready twelve thirty, and over by two. Train leaves two thirty for Topeka.”[64]

Wells received an official invitation for the use of the Opera House from Richmond’s prominent citizens, offering “free use of The Opera House” for the dedication services and everything else “to Accommodate those who may attend, and we shall be glad to assist In Making the Occasion as Agreeable and pleasant as possible for your People and Citizens generally.”[65]

Wells replied to the invitation while he was in New York conferring with Stephens, the choir’s conductor, and George Pyper. He wrote in part: “Permit me to acknowledge the favor of your communication of the eighth. . . . I am deeply grateful for this courtesy, and assure you that it will be highly appreciated by the officials and members of the Church I represent. It is with pleasure that we accept the use of the opera house, and that I am able to say that the dedicatory service will be conducted there by officials of the Church, with the Tabernacle Choir in attendance, on Wednesday morning, 22nd November, 1911, at 10 o’clock.”[66]

Wells forwarded the invitation to President Joseph F. Smith from New York on November 11. Wells wrote: “I enclose herewith correspondence respecting the use of the Opera House, for the Dedicatory Service of the Oliver Cowdery monument, at Richmond. This explains itself, and discloses, as you will see, a very friendly interest on the part of the people there. The names signed are those of the “principal bankers, merchants, one of the ministers, the Mayor of the City, hotel proprietors, and the owner of the Opera House.”[67] Wells was “deeply grateful for this courtesy”[68] and reported to President Joseph F. Smith that there was “a feeling of great interest and enthusiasm, already manifest by the people at the prospect of so large a company being present.”[69]

The Farris Opera House, ca. November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. The opera house underwent a $500,000 renovation in 1999 and is still used today as a theater for live stage performances, movies, and community functions. (Photo probably by John Encore, Church History Library)

The Farris Opera House, ca. November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. The opera house underwent a $500,000 renovation in 1999 and is still used today as a theater for live stage performances, movies, and community functions. (Photo probably by John Encore, Church History Library)

After sending President Smith a mock-up of the invitation, Wells awaited Smith’s approval and information concerning who would be present on the occasion. Mindful of the weather, he noted: “If we can only have a pleasant day, it promises to be a very fine affair.”[70] President Smith wrote back that the gathering would be more limited than Wells may have anticipated. He assigned Elder Heber J. Grant of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles to conduct the affairs of the Church at the services.[71] Wells noted in later reflections why other general officers were not sent to attend the occasion: “Conditions at home were so forbidding that the Presiding Authorities were not able to go to the service.”[72] The conditions referred to were the November municipal elections in Utah. Since 1905, the anti-Mormon third party, known as the American Party, controlled several local governments in the northern part of the state, including Salt Lake City. The two national parties made every effort to defeat the American Party. Church leaders joined in forces with non-Mormons in both parties to help accomplish the defeat. The campaign successfully brought about the demise of the American Party and allowed political affiliation in the state to be based on political preference instead of Church membership.[73]

President Smith indicated in his letter that he did not feel it necessary to invite representatives from the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints or the Church of Christ (Temple Lot). This decision is significant because of the Reorganized Church’s ties to the American Party. Joseph Smith III (cousin of President Joseph F. Smith) and his son, Fredrick M. Smith, had worked with Frank Cannon and ex-Senator Kearns to form the American Party in Salt Lake City.[74] Moreover, in July 1905—when the American Party first began to take root—Frederick Smith wrote a full-page protest of the Joseph Smith monument that the Church had recently erected in Vermont under Wells’s supervision.[75]

After receiving President Smith’s approval for the proposed invitation, Wells ordered 750 formal invitations, printed at a cost of fifteen dollars.[76] On November 14, Wells wrote Burnett Hughes, cashier of the Banking House of J. S. Hughes & Company in Richmond: “The invitations together with envelopes were sent by express today from the printing establishment of Biglow & Company and should reach you some time on Thursday or Friday morning. There are 450 of them, which may be more than you will care to send out. I had this number forwarded thinking that there might be some spoiled and that there might be some intended to go at a distance to people would not attend.” Wells noted anxiously: “Of course it is important to avoid confusion and disappointment to be sure that a perfect list is made and kept of those to whom invitations are sent and that provision is made to seat them if they come. I have reserved 100 to be sent to people in addition to the above, and it may be that in case you need a few more some of those might be available after I reach Richmond. Should extra chairs be put in, it may be that even 600 invitation could be issued. I have that many printed in case of need.” Finally, he stated, “I wish you would tell Mr. [L. J.] Ferris [owner of the Opera House] to be sure and have the rising platform well supported and very strong so that there will be no danger of an accident.”[77] Wells sent out invitations to numerous Church officials, including all mission, temple, stake and Church college presidents so that “Representatives of the Church in all the World were officially notified of the proceeding of the day and their approval wired.”[78]

On November 16, Wells wrote Bowers regarding final payment for the monument and added his impressions regarding the final product: “I think the material and workmanship of the monument are very good, and that it will be much admired.” He noted hopefully, “It will look well when the grades I have under way are completed with a new fence and other improvements at the cemetery. Look for me about the first of December.”[79]

Work began on preparing the ground around the monument for the unveiling ceremony. Wells contracted with Charles E. Prispin to grade the area and Powell Brothers to fence the west and north side of the cemetery.[80]

The citizens of Richmond not only offered the use of the Opera House for the dedication service, but they also graded streets, paved sidewalks, and laid plank crossings at several corners. Several individuals, especially George W. Schweich, offered more assistance than Wells ever expected. So it was with great hope and a sense of satisfaction that Wells greeted the long-awaited day of the dedication service and unveiling ceremony on November 22, 1911.

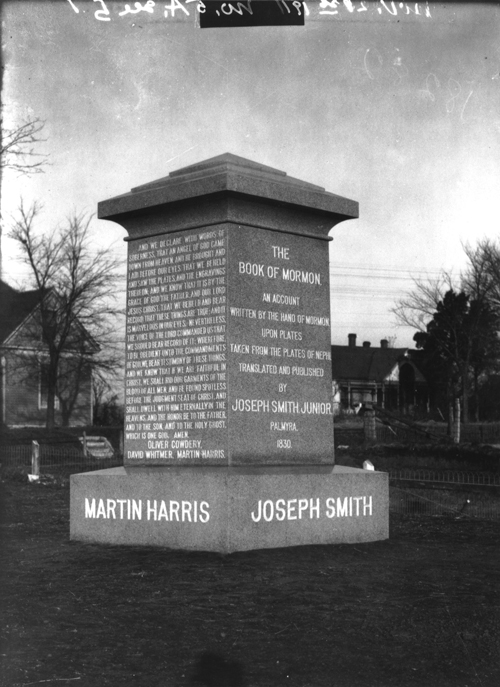

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 21, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On the reverse side is inscribed "The Title Page of the Book of Mormon" from the first edition, printed in Palmyra, New York, in 1830. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 21, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On the reverse side is inscribed "The Title Page of the Book of Mormon" from the first edition, printed in Palmyra, New York, in 1830. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

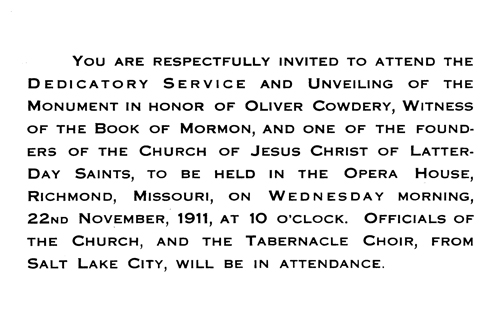

Printed invitation for dedication service and unveiling of the monument. (Church History Library)

Printed invitation for dedication service and unveiling of the monument. (Church History Library)

The Dedication Services and Unveiling Ceremony

A train of Pullman Palace sleeping cars pulled in to Richmond from Kansas City during the early morning hours of November 22, 1911 (fig. 8). While the train sat on a side track, members of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir continued to sleep until sunrise. Wells provided a description of the choir’s arrival: “The train bringing the choir from Kansas City arrived during the night, or early in the morning of the 22nd. It was not easy to rouse the weary sleepers, and get them out, under lowering skies, at half-past seven for early breakfast, at the hotel. It was, however, loiteringly accomplished, but not until the prince and power of the air, or whoever has charge of the storm clouds, had taken vicious control and started a downpour of chilling art of the day.”[81]

Arrival of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Arrival of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Following breakfast at the hotel, the choir made its way to the Farris Opera House. Wells paid $12.00 for Manley & Wading to transport the “choir from the Hotel to the Opera House” in the rain.[82] Anderson apparently was not the only photographer present on the occasion. On November 23, Wells had paid John Encore $8.40 “for pictures.”[83] Two images not found in the Anderson collection in Salt Lake City appear in the January 1911 issue of the Improvement Era, and may have been taken by Encor at the time or previously.[84] Wells prepared 1,500 programs for the dedication service and unveiling ceremony, costing forty-two dollars for the artwork and printing.[85] The dedication program measures 6 5/

The local newspaper, Richmond Conservator, reported: “The services were held in the Farris Theatre and the house was well filled, there being hardly a vacant seat in the building.” The paper added, “Besides the choir there were a number of the notable members of the Mormon faith here, some of the leading men and officials of the church.”[86]

Mormon Tabernacle Choir Train, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. A special train brought the choir from Kansas City, arriving early in the morning. Here several members, including Evan Stephens (arms outstretched), pose for George Edward Anderson. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Mormon Tabernacle Choir Train, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Missouri. A special train brought the choir from Kansas City, arriving early in the morning. Here several members, including Evan Stephens (arms outstretched), pose for George Edward Anderson. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Elder Heber J. Grant greeted the crowd, followed by the Tabernacle Choir performing the first hymn, “An Angel from On High” President Samuel O. Bennion offered the invocation, and the Tabernacle Choir sang the Hosannah Anthem. Then Junius F. Wells “spoke in brief as to why we were assembled,” reviewing the story of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, the life of Oliver Cowdery, the history of the monument itself.” In the end, he spoke to the local residents suggesting “that the cemetery be improved and that the citizens of Richmond would regard that monument as a credit to the place.” The Tabernacle Choir sang one its favorite hymns, “O! My Father,” followed by comments from Mayor James L. Farris in behalf of the city stating to the Latter-day Saint visitors: “Take possession of the City of Richmond, today we are your servants.” The assembled group then heard brief remarks from George W. Schweich, who represented Oliver Cowdery’s family, welcoming everyone present to the occasion. After Schweich’s introduction, Edith Grant Young sang a solo, “Who Are These Arrayed in White?”[87]

The order of the program was modified at this point as result of inclement weather. Elder Grant’s talk followed the Tabernacle Choir’s rendition of “God Is Our Refuge.” He noted how pleased President Joseph F. Smith had been that a monument was erected to honor Oliver Cowdery. He went on to relate that he had always admired Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris, who played such crucial roles in establishing the Church. As he drew near to the close of his remarks, Elder Grant “bore his testimony of the gospel to the assemblage, gave words of praise to the Choir for their conduct and singing. Elder Grant also expressed his pleasure in accepting hospitality of Richmond people. He also stated that on account of the storm they would be unable to go to the cemetery to dedicate the grave.” After Elder Grant’s remarks, Wells introduced Kathryne Schweich, grandniece of Oliver Cowdery, to the assembled group. He noted that she would unveil the monument when weather permitted. She “very modestly acknowledged the honor before the audience.” Elder Heber J. Grant then dedicated Oliver Cowdery’s grave from the Farris Opera House, thanking God “for the feeling of goodwill and fellowship that has been manifest by the inhabitants of this City during the erection of this monument and we pray Thee that it may continue and that the bond of love and sympathy between the believers of the Book of Mormon and the people of Richmond and those who read the message may grow and increase in strength every year.”[88]

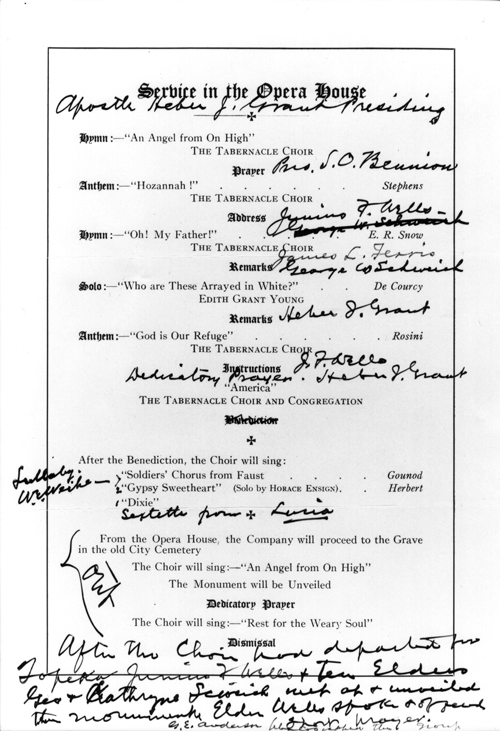

Junius F. Wells's personal copy of the printed program for the dedication service and unveiling ceremony with his handwritten notations regarding participants and detailing the changes made because of the weather conditions, which forced the assembly to remain in the Farris Opera House. (Church History Library)

Junius F. Wells's personal copy of the printed program for the dedication service and unveiling ceremony with his handwritten notations regarding participants and detailing the changes made because of the weather conditions, which forced the assembly to remain in the Farris Opera House. (Church History Library)

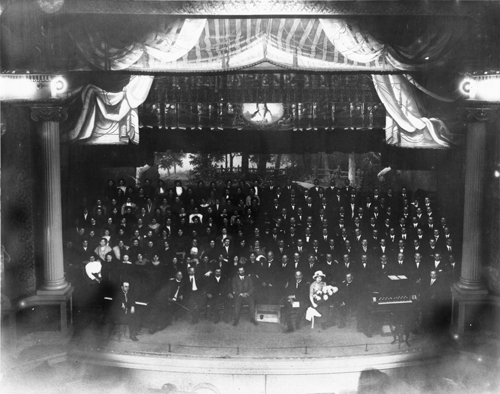

Dedication service in the Farris Operas House, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On the front row are John J. McClellan (organist), Willard A. Weihe (violinist), George W. Schweich (grandson of David Whitmer), Samuel O. Bennion (Central States Mission president), Bishop David A. Smith (Presiding Bishop's office), Evan Stephens (Tabernacle Choir Director, standing), Elder Heber J. Grant (Council of the Twelve), Katherine Schweich (great-granddaughter of David Whitmer, holding flower bouquet), and Junius F. Wells. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Dedication service in the Farris Operas House, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. On the front row are John J. McClellan (organist), Willard A. Weihe (violinist), George W. Schweich (grandson of David Whitmer), Samuel O. Bennion (Central States Mission president), Bishop David A. Smith (Presiding Bishop's office), Evan Stephens (Tabernacle Choir Director, standing), Elder Heber J. Grant (Council of the Twelve), Katherine Schweich (great-granddaughter of David Whitmer, holding flower bouquet), and Junius F. Wells. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Time was allotted for George Edward Anderson to take a photograph of “the Choir and Guests of Honor” (fig. 11).[89] Wells described the setting of the photograph:

“The singers were upon the stage of the beautiful opera house—guests there upon invitation of the leading citizens—town and country officials, bankers, merchants, lawyers, and farmers who had prepared to receive them, and greet them in honor, in cordial welcome with applause and praise. These, and the people generally, were congregated to the utmost capacity of the house, listening with amazement and delight to the beautiful harmony, gazing with astonishment and unfeigned wonder upon the perfect picture of refined and beautiful womanhood—virile and noble manhood—culture, art, music, intelligence, skill, talent akin to genius, exhibited before them—a living testimony.”[90]

Following the photographic interlude, the audience joined the choir and sang “America.” This was followed by a series of musical numbers by the Tabernacle Choir and soloists: “Soldiers’ Chorus from Faust,” a violin solo by Willard Weihe; “Way Down Upon the Sewanee River;” the tune “Dixie” by the Choir; and finally a solo by Horace Ensign, “Gypsy Sweetheart.” George Schweich made the program’s closing remarks, saying that he was as proud to be a descendant of David Whitmer as of “any monarch that ever lived.” He asked the Tabernacle Choir to perform a few concluding numbers before the program ended, including “Lucia Sextet.” The choir performed, and Bishop David A. Smith then offered the benediction to close the service.[91] Wells reported that “the visitors [Tabernacle Choir and Church representatives] hurried through the rain to the hotel for dinner, and about half-past one, their train pulled out for Topeka, Kansas.... Elders Grant and Bennion accompanied them.”[92]

Unveiling Ceremony at the Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Unveiling Ceremony at the Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Later in the afternoon, when the weather permitted, Wells and a small party proceeded to the cemetery. George Edward Anderson accompanied them and provided some beautiful black-and-white images of the occasion (figs. 12, 13).

Wells preserved the details regarding the monument’s unveiling: “The following named Elders, Geo. W. Schweich & his daughter Kathryrn met with Geo. Ed Anderson & me at about 3 p.m. at the monument and I spoke to them & offered prayer & Kathryn held the flag that veiled the monument while we all had our pictures taken” (figs. 14, 15, 16, 17).[93]

Unveiling ceremony at the Oliver Cowdery monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. Junius F. Wells stands to the left of Katherine Schweich, who holds the bouquet of flowers following the unveiling of the monument. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Unveiling ceremony at the Oliver Cowdery monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. Junius F. Wells stands to the left of Katherine Schweich, who holds the bouquet of flowers following the unveiling of the monument. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Junius F. Wells offers a prayer following the unveiling of the monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Junius F. Wells offers a prayer following the unveiling of the monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

The Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. The last images of the monument were taken at the end of the day, following the dedication service and unveiling ceremony. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

The Oliver Cowdery Monument, November 22, 1911, Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. The last images of the monument were taken at the end of the day, following the dedication service and unveiling ceremony. (Photo by George Edward Anderson, Church History Library)

Assessment

The local paper in Richmond provided its assessment of the service: “The musical numbers rendered by the choir were excellent and showed their fine training and splendid voices.... The remarks by the speakers were to the point and interesting. Apostle Heber Grant of Salt Lake City, made the longest talk and was very interesting.... The arrangements and plans were carried out and everything worked smoothly. Mr. Wells had been here for several days and with Geo. W. Schweich, a grand son of David Whitmer, had everything in readiness for the event.”[94]

Everyone seems to have been pleased with the events of the day and happy to have participated in celebrating the life of Oliver Cowdery. Junius F. Wells fulfilled President John Henry Smith’s pledge to George W. Schweich to honor Cowdery by placing a monument in the Old City Cemetery in Richmond, Ray County, Missouri. Wells may have captured, at least on one level, the significance of the day when he talked about the members of the community, including clergymen, bankers, merchants, county and city officials, and the leading citizens who gathered in the Opera House and “wept for joy, as they participated in this song service. They were also admonished in words of stirring testimony and convincing reason of the truth, the life, the immortality and saving grace of the doctrines and government of the Church, as they fell from the lips of descendants of the very men who had been well nigh hounded to death in the public square near by.”[95] This day, however, provided a different setting for the interaction between the Latter-day Saints and the people of Missouri as they celebrated together to honor one of their own.

Notes

This is an expanded version of a paper published previously by the authors under the same title in BYU Studies 44, no. 3 (2005): 99–121.

[1] Oliver Cowdery, Martin Harris, and David Whitmer, “The Testimony of the Three Witnesses,” in Joseph Smith Jr., History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed., rev., 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1971), 1:57.

[2] Junius F. Wells (1854–1930), son of Daniel H. and Hannah C. Free Wells, was asked to organize the Church’s Young Men’s Mutual Improvement Association (YMMIA) in 1875 and became its first president.

[3] Junius F. Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” Improvement Era, January 1912, 251.

[4] Samuel O. Bennion (1874–1945) arrived in Missouri in 1904 and was eventually called to preside over the Central States Mission (including Missouri) in 1906, serving there until 1934. John L. Herrick (1860–1960) was president of the Western States Mission at the time, serving from 1908 to 1919. Joseph A. McRae (1865–1958) was president of the Western States Mission from 1901 to 1908.

[5] Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery (1815–92) was the daughter of Peter and Mary Musselman Whitmer. For more information about her life, see Ronald E. Romig, “Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery: A Historical Reflection of Her Life,” in this volume.

[6] For more information on the deaths of Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery, her husband Charles Johnson, and their daughter Maria Louise Cowdery Johnson, see Alexander L. Baugh, “Separated from Oliver in Death: The Elizabeth Ann Whitmer Cowdery Memorial Dedication,” Mormon Historical Studies 7, nos. 1–2 (Spring/

[7] David Whitmer is buried in the Richmond City Cemetery, located on Highway 10, just west of Richmond City Center. Oliver Cowdery, along with many other Whitmer relatives, including Peter Whitmer Sr. and Mary Musselman Whitmer, are buried in the Pioneer Cemetery, located on Highway 13, just north of the center of town (Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and T. Jeffery Cottle, Old Mormon Kirtland and Missouri: Historic Photographs and Guide [Santa Ana, CA: Fieldbrook, 1991], 215–16; also LaMar C. Berrett and Max H. Parkin, Sacred Places, Missouri: A Comprehensive Guide to Early LDS Historical Sites, Volume 4 [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004], 260–64).

[8] John Henry Smith, Diary, November 30, 1910, John Henry Smith Papers, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. All quotations from Smith’s diary are from Jean Bickmore White, ed., Church, State, and Politics: The Diaries of John Henry Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1990).

[9] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251.

[10] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251.

[11] See Keith A. Erekson, “American Prophet, New England Town: The Memory of Joseph Smith in Vermont” (MA thesis, Brigham Young University, 2002).

[12] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251.

[13] Junius F. Wells to Heber J. Grant, August 26, 1924, Church History Library. All primary source materials are found in the Junius F. Wells Papers, 1867–1930, at the Church History Library unless otherwise noted. In the letter, Wells maintains that John Henry Smith promised him that additional monuments would be erected. He writes: “In 1918 the matter came up again for completing the plan and after a long consideration and favorable report being made by a committee of the Apostles a contract with me was authorized for the immediate erection at the grave of Martin Harris for the sum of $5800, with the further recommendation that I should also have the contract to erect the one promised at David Whitmer’s grave later on—(The promise to do this was originally made by President John Henry Smith & virtually repeated at the dedication of Oliver Cowdery’s in 1911.) As I was called to go upon a mission to Europe before the contract for the Harris monument was actually executed, it was decided to postpone the matter until my return” (Junius F. Wells to Heber J. Grant, August 26, 1924). Neither a monument to Harris nor to Whitmer came to fruition under Wells’s direction.

[14] David Lowenthal, The Past Is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 121.

[15] Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: A. A. Knopf, 1991), 93. Kammen notes, “Various sorts of signposts assist in setting that era apart. In 1869, for instance, the Corcoran collection of art opened as a gallery in Washington, D.C., for the ‘encouragement of American genius’; and an essay titled ‘Americanism in Literature’ appeared in January [1870] with this assertion: ‘It is better that a man should have eyes in the back of his head than that he should be taught to sneer at even a retrospective vision’” (Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory, 93).

[16] Kamman, Mystic Chords of Memory, 93–296; G. Kurt Piehler, Remembering War the American Way (Washington: Smithsonian, 1995); and David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

[17] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251.

[18] Erekson, “Memory of Joseph Smith in Vermont,” 59–101.

[19] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, February 13, 1911. Bowers’s reference to multiple monuments presumably has to do with Wells’s ostensible desire to erect a monument for each of the other Book of Mormon witnesses.

[20] Junius F. Wells to R. C. Bowers, March 25, 1911.

[21] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, March 30, 1911.

[22] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, April 7, 1911.

[23] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, April 19, 1911.

[24] “Agreement,” May 19, 1911. Anthon H. Lund (1844–1921) had served as first counselor since April 7, 1910.

[25] Wells’s published timeline, written nearly six months after the event, does not match the primary source record. Because he made several visits to Richmond within the space of three months, he probably could not recall the exact details of what happened during each visit (Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251).

[26] Milton R. Merrill, Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1990), 33. Merrill writes, “From the time of the first public announcement of Smoot’s candidacy, the newspapers of the country gave attention to the Utah situation. Many of the published news stories emanated from Salt Lake City, and the majority of them were critical.”

[27] George Schweich to Junius F. Wells, May 27, 1911.

[28] George Edward Anderson’s notation on the glass plate edge of this photograph proves that this image was taken in 1911 and not, as previously thought, in 1907.

[29] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 253.

[30] George Schweich to Junius F. Wells, May 27, 1911.

[31] George Schweich to Junius F. Wells, May 27, 1911.

[32] Junius F. Wells to Heber J. Grant, August 26, 1924.

[33] Geraldine H. Clayton, “Utah State Capitol Building,” Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allan Kent Powell (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), 598–99.

[34] Smith, Diary, June 9, 1911, as cited in White, Church, State, and Politics, 672.

[35] Smith, Diary, June 12, 1911, as cited in White, Church, State, and Politics, 673.

[36] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 251.

[37] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, June 15, 1911.

[38] R. C. Bowers to M. H. Rice, June 15, 1911.

[39] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, August 4, 1911.

[40] Philander Alma Page (1832–1919) was the son of Hiram Page, Cowdery’s wife’s brother-in-law. Julia Ann Whitmer Schweich (1835–1914) was David Whitmer’s daughter and Cowdery’s niece. George W. Schweich (1853–1926) was son of Julia Ann Whitmer Schweich, grandnephew of Cowdery.

[41] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 255–56.

[42] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 257.

[43] “Certificate of Authority,” August 8, 1911.

[44] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 254–55.

[45] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 259–60.

[46] Junius F. Wells to W. A. Mullins, August 18, 1911.

[47] “Petition,” August 15, 1911.

[48] I. R. E. Brown to Honorable Mayor and City Council of Richmond, Mo., August 16, 1911.

[49] Junius F. Wells to J. W. Hagans, August 18, 1911.

[50] “Certificate,” October 26, 1911. The books included the Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, Pearl of Great Price, and volume one of B. H. Roberts’s Comprehensive History of the Church. The periodicals included issues of publications then printed by various Church organizations as well as a few that were no longer in publication: Deseret News (1850–present), Woman’s Exponent (1872–1914), Improvement Era (1897–1970), Young Woman’s Journal (1889–1929), Juvenile Instructor (1866–1929), Children’s Friend (1902–70), and the Contributor (1879–96).

Wells chose a volume from the discontinued Contributor because it contained an article by George Reynolds on the history of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon. Also included was a beautiful steel engraving of the Three Witnesses: Oliver Cowdery, David Whitmer, and Martin Harris. The photographs deposited included views of Salt Lake City and portraits of U. S. President William H. Taft, Oliver Cowdery, Joseph Smith, Hyrum Smith, Lucy Smith, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, John Taylor, Lorenzo Snow, Joseph F. Smith, Anthon H. Lund, John Henry Smith, David Whitmer, George W. Schweich, and Julia Whitmer Schweich. The miscellaneous items included statistical information about Utah and the Church (sixty-two stakes, twenty missions, and 690 wards), a current Church directory of officers, programs from an “Old Folks Reception to William H. Taft, President of the U. S.” and the “Proceedings of the Dedication of the Joseph Smith Monument, at his birth place Sharon, Vermont, 1905.”

[51] Susan Easton Black, “Pioneer Cemetery: Richmond, Ray County, Missouri,” Mormon Historical Studies 2, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 183.

[52] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, August 21, 1911.

[53] Wells, “Oliver Cowdery Monument,” 263.

[54] This photograph has been mistaken to be “the base of the obelisk erected in 1905 at Joseph Smith’s birthplace in the township of Sharon, Vermont” (Richard H. Jackson, “Historical Sites,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow and others, 5 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 2:592; see also Douglas F. Tobler and Nelson B. Wadsworth, The History of the Mormons in Photographs and Text: 1830 to the Present [New York: St. Martin’s, 1989], 63).

[55] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 263.

[56] Junius F. Wells to R. C. Bowers, October 10, 1911.

[57] R. C. Bowers to Junius F. Wells, October 10, 1911.

[58] Junius F. Wells to Thomas Blount, October 14, 1911.

[59] Junius F. Wells to R. C. Bowers, November 16, 1911.

[60] Junius F. Wells to Thomas B. Blount, November 4, 1911.

[61] Junius F. Wells to George D. Pyper, October 29, 1911.

[62] Junius F. Wells to George D. Pyper, October 29, 1911.

[63] Joseph F. Smith to Junius F. Wells, November 2, 1911. Smith’s mention of “Bennion” refers to Samuel O. Bennion, mission president over Missouri.

[64] Junius F. Wells to H. B. McIntyre, November 9, 1911.

[65] J. M. Ferguson and others to Junius Wells, November 8, 1911.

[66] Junius F. Wells to J. M. Ferguson and others November 11, 1911.

[67] Junius F. Wells to Joseph F. Smith, November 11, 1911.

[68] Junius F. Wells to J. M. Ferguson and others, November 11, 1911.

[69] Junius F. Wells to Joseph F. Smith, November 11, 1911.

[70] Junius F. Wells to Joseph F. Smith, November 11, 1911.

[71] Heber J. Grant (1856–1945) was ordained a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1882. Later he served as President of the Church from November 1918 to May 1945.

[72] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 265.

[73] Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890–1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 16, 29–30, 32–33, 38–39.

[74] Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 16, 29–30, 32–33, 38–39.

[75] Frederick M. Smith, “Open Letter to All People,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 1, 1901, 3. Smith’s article was actually less of a protest against the monument and more of a polemic against the Latter-day Saint Church’s practice of polygamy, including the controversy surrounding Apostle Reed Smoot’s senatorial candidacy. His mention of the monument was a foil used to initiate arguments against the church that, given the contemporary political climate and his involvement in the American Party’s organization, might have been posed as political concerns that would become the tenets of the American Party.

[76] Junius F. Wells to L. H. Biglow, November 15, 1911.

[77] Junius F. Wells to Burnett Hughes, November 14, 1911.

[78] “Invitations,” November, 22, 1911.

[79] Junius F. Wells to R. C. Bowers, November 16, 1911.

[80] Junius F. Wells to Charles E. Prispin, November 23, 1911; “Powell Brothers Receipt,” November 23, 1911.

[81] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 267.

[82] “Manley & Wading Receipt,” November 23, 1911.

[83] “John Encore Receipt,” November 23, 1911. Anderson and Encore were well acquainted, having met in 1907 when Anderson was taking his first photographs of Church historical sites in Missouri (Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, T. Jeffrey Cottle, and Ted D. Stoddard, Church History in Black and White: George Edward Anderson’s Photographic Mission to Latter-day Saint Historical Sites [Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995], 75–76).

[84] See Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 254, 256–58.

[85] Junius F. Wells to L. H. Biglow, November 15, 1911.

[86] “Tabernacle Choir Here,” Richmond Conservator, November 23, 1911.

[87] “Minutes of the Dedicatory Service and Unveiling of the Oliver Cowdery Monument,” November 22, 1911. Apparently, the report was prepared by Louise Dansie of the Central States Mission Office. See Louise Dansie to Junius F. Wells, November 27, 1911. Edith Grant Young (1885–1947) was a daughter of Heber J. Grant and member of the Tabernacle Choir.

[88] “Minutes of the Dedicatory Service and Unveiling of the Oliver Cowdery Monument.” President Grant’s comment regarding David Whitmer being buried in the same cemetery as Oliver Cowdery is inaccurate. Whitmer was in fact buried in the New City Cemetery west of Richmond.

[89] George Edward Anderson was apparently not the only photographer present for the occasion. As note previously, on November 23, Wells paid John Encore $8.40 “for pictures” (John Encore Receipt, November 23, 1911).

[90] “Six Thousand Miles with the ‘Mormon’ Tabernacle Choir,” Juvenile Instructor, July 1913, 448.

[91] “Minutes of the Dedicatory Service and Unveiling of the Oliver Cowdery Monument.”

[92] Wells, “The Oliver Cowdery Monument at Richmond, Missouri,” 272.

[93] Junius F. Wells, November 22, 1911.

[94] “Tabernacle Choir Here,” Richmond Conservator, November 23, 1911.

[95] “Six Thousand Miles with the ‘Mormon’ Tabernacle Choir,” 448.