The Ancestors of Israel and the Environment of Canaan in the Early Second Millennium BC

George A. Pierce

George A Pierce, “The Ancestors of Israel and the Environment of Canaan in the Early Second Millennium BC,” in From Creation to Sinai: The Old Testament through the Lens of the Restoration, ed. Daniel L. Belnap and Aaron P. Schade (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 163‒92.

One challenge for any reader of the Old Testament is trying to understand the historical context for the people and narratives found in the text, since readers are separated from those events by thousands of years. What the daily life of these individuals would have been like can be hard to imagine. Yet the more one knows of the historical context, the more one can relate to the given individual. In this chapter, George A. Pierce provides such a context to the ancestral narratives of Genesis 12–50, those narratives concerned with the families of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph. While the author does not discuss the narratives themselves in detail, he does provide a scaffolding to recognize the world they lived in and, in so doing, gain an appreciation of their experience. —DB and AS

The narrative of Genesis 11:31–32 declares that Terah and his family—comprising Abram (later Abraham), Sarai (later Sarah), Lot, and other retainers—left their homeland bound for Canaan and dwelt in Haran for a period during which Terah passed away.[1] While in Haran, Abraham received the initial covenant call to leave his family group and sojourn in a land that the Lord would show him (Genesis 12:1).[2] From this point forward, the literary narrative of Genesis focuses its attention on this man and his promised offspring who would become the ancestors of the covenant people of Israel. An awareness of the historical, environmental, sociocultural, archaeological, and economic contexts underlying the ancestral narratives of Genesis 12–50 should help readers to develop a deeper appreciation for the theological message of the biblical record; that is, knowing about the trials and lives of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob may provide us instruction and guidance in our modern world. Unpacking the complete context of the ancestral narratives would entail a greater space than allotted here. Thus, this paper presents an archaeological and historical overview of Canaan in the second millennium BC during the period known as the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1950–1550 BC), situating Abraham and his family members in their geographic and cultural contexts and examining the economic interactions between the ancestors of Israel and the land of Canaan and its inhabitants.[3] Combined, these efforts suggest an archaeological signature for the ancestors and reshape modern expectations in terms of extant material culture versus received literary legacy.

Alan Millard relates that “the discussion of Genesis cannot stay in the literary sphere; it reaches out into history and religion, and cannot expect to reach anything approaching a full appreciation of the book without doing so, just as a full appreciation of Shakespeare’s plays includes [an] understanding of the Elizabethan theatre and audience.”[4] Therefore, a study of the ancestors of Israel should include an understanding of the natural and cultural environment of Canaan, the stage upon which the ancestral narratives unfolded. While many aspects of the land of Canaan during this period are lost to the ages, scientific data derived from climate studies and archaeological excavations, coupled with historical data interpreted from ancient texts and the Bible, can greatly inform the student of the Old Testament about the land in which Abraham and his descendants sojourned.[5]

Canaan in the Second Millennium BC

The beginning of the Middle Bronze Age in Canaan is marked by the establishment of palatial and fortified centers, monumental architecture, and international trade.[6] Although outside the chronological scope of this study, the preceding Early Bronze Age (ca. 3400–1950 BC) was a formative period in the settlement history of Canaan in which an initial phase of urbanization and the formation of territorial states occurred. Bronze Age settlement patterns took advantage of elements needed for the establishment of permanent sites concentrated on aspects of agriculture and pastoralism such as being in close proximity to a permanent source of water and having land cleared or ready for agriculture.[7] During this period, Egypt established trade relations with inland sites in Canaan and with coastal centers, both of which supplied the Egyptian courts with items not found in Egypt like timber, bitumen, copper, and turquoise. Collapse of this urban culture occurred abruptly about 2200 BC as sites across the Near East were abandoned or destroyed. Climate data indicate that a shift to a warmer and drier climate led to the abandonment of cities in Canaan and Syria, events that coincided with the demise of Egypt’s Old Kingdom and the downfall of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia. Climatic phenomena such as famines would later play an important role in the story of Abraham.

The reurbanization of Canaan at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age was a process whose whole was greater than the sum of its various parts. Canaan transformed from a largely rural population with ephemeral archaeological remains into an urban society with settlement hierarchies and extensive trade networks that were of a greater diversity in size, function, and distribution of sites and that had expanded into previously unexploited environmental niches. The Middle Bronze Age material culture was the result of multiple internal and external factors such as population movements, trade, and communication, in addition to cultural continuity. A study of the Canaanites provides the cultural background of the people among whom the ancestors sojourned (Genesis 12:6) and against whom the Israelites would later fight to conquer the land promised to Abraham and to struggle to resist spiritual corruption and idolatry.

The Natural Environment: A Reconstruction of Canaan’s Climate

Understanding Canaan as Abraham experienced it includes a reconstruction of the climate of Canaan in the early second millennium BC. Such efforts are necessary given the shifts in global climate, changes in local topography and hydrology, presence of intrusive vegetation, and decrease or disappearance of animal ranges. Reconstructing paleoclimates and past landscapes can be accomplished through a variety of scientific avenues.[8] Determining the effects of climatic shifts on the population of Canaan requires reconstructing the ancient climate of the eastern Mediterranean basin, which can be accomplished in a number of ways, including oxygen isotope analysis and the use of ice and sediment cores, lithology, and palynology.[9] Despite uncertainties when analyzing these proxies and relating them to natural processes or climatic events, the approaches treated here form the best information to propose the environmental and climatic conditions of Canaan in the Middle Bronze Age.[10] While the temptation exists to apply the specific information provided by specialist studies for a wider area than originally intended or to employ extraregional data by analogy, careful synthesis of all the information can present a fuller picture of a region’s past landscape and climate as well as the social, political, and economic strategies employed by its inhabitants.

Employing various methods permits a synthetic overview of climate for the Levant for the period before the arrival of Abraham and his household and the duration of the ancestors’ sojourn in Canaan before Jacob moved his family to Egypt (Genesis 46:5–27). Toward the end of the third millennium BC, climatic warming resulted in lake levels dropping, rivers becoming seasonal, and deserts expanding. Aridification of the Near East resulted from lower rainfall related to cooling of subpolar and subtropical surface waters of the North Atlantic.[11] This major crisis, lasting about a century from 2200 to 2100 BC, included a drop in the Dead Sea water level of nearly 100 meters and the drying up of the southern basin, a rise of oceanic levels of 1.5 meters, and a decrease in olive pollen and a rise in oak and pistachio pollen around the Sea of Galilee, indicating a decline in olive cultivation and in the permanent settlements’ abilities to maintain such olive groves.[12] The beginning of the Middle Bronze Age witnessed a reversal of these trends as the climate became cooler and more humid through about 1800 BC, when wetter events are recorded.[13] Increased rainfall, the growth of cypress and willow trees in wetter environments along river banks, the renewed cultivation of olives, and a decrease in oak forests are all indicated by various environmental data; thus, the land of Canaan was not an entirely hot, dry, and foreboding landscape wherein Abraham’s family would have struggled to survive, but it was a cooler region with higher rainfall and more lush vegetation that allowed settlements to flourish in marginal areas like the biblical Negev and the location of Beersheba and Gerar (see Genesis 20; 21:22–32), locations that are very dry and barren today.

The Sociocultural Environment of Canaan

Limited religious, administrative, and personal documents from ancient Canaan have been found archaeologically. Indeed, the Canaanites did not leave behind textual records clearly defining who they were and what it meant to be a Canaanite. Archaeology indicates that the Canaanites have a shared cultural heritage with other groups in the Near East (ranging from Mesopotamia to Egypt) termed “Amorite,” a group name that also appears in the Old Testament. Scholars have suggested that certain aspects of Canaanite society, including architecture, crafts, and language, originated in eastern Syria with the Amorites and that the Amorite peoples or culture spread throughout the Near East during the Middle Bronze Age.[14] This can especially be seen in Amorite names for rulers and sites in Syria and Canaan—names found in the Execration Texts, a set of Middle Kingdom Egyptian ritual texts meant to magically bind and break the power of Egypt’s foreign enemies.[15] Personal names in an administrative document from Hebron reflect a mixture of Amorite and Hurrian names, suggesting that Abraham would have interacted with a mixed population while he dwelt near Hebron and may have been integrated into a diverse community as a nonnative inhabitant of Canaan.[16] These suggestions help paint the ethnically diverse backdrop of Abraham’s purchase of the cave of Machpelah as a burial place for his family (Genesis 23). In addition to Amorite names, other features such as defensive works, entombments beneath houses and palaces, temple architecture, donkey burials, and pottery also indicate either a transmission of knowledge or a migration of people from a core area in eastern Syrian and northern Mesopotamia to places like Canaan.[17] Abraham and his family may have found themselves in the midst of these waves of migrations of diverse peoples throughout the region. While the archaeological record shows that the Amorite culture was clearly dominant in Canaan, it should be noted that the Canaanites were a multicultural amalgamation of people who shared many traits in common. This accords well with the statement by the Lord through the prophet Ezekiel, who reminded the city of Jerusalem of its Canaanite roots: “Your origin and your birth were in the land of the Canaanites; your father was an Amorite, and your mother a Hittite” (Ezekiel 16:3 NRSV).

To assume that the Canaanites were a single group of people would be incorrect, and the Bible and the Book of Abraham portray Abraham amid diverse communities of people. Extrabiblical texts from Canaan suggest that most people during the Bronze Age would not have considered themselves “Canaanite” but would have identified with a tribal ancestor or with a city or territory in which they lived. The biblical table of nations in Genesis 10:15–18 NRSV suggests that a patchwork of peoples and places comprised the Canaanites, including Sidon (presumably the eponymous ancestor of the Phoenician city bearing that name), Heth, “the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, the Hivites, the Arkites, the Sinites, the Arvadites, the Zemarites, and the Hamathites.” Genesis 15:19–21 lists “the Kenites, and the Kenizzites, and the Kadmonites, and the Hittites, and the Perizzites, and the Rephaims, and the Amorites, and the Canaanites, and the Girgashites, and the Jebusites” as the inhabitants of the land promised to the would-be patriarch Abraham.

The few Egyptian texts dated to this period that concern Canaan offer some tantalizing evidence about the natural environment and social organization of the Levant in the Middle Bronze Age. The Tale of Sinuhe is a Middle Egyptian tale detailing the experiences of an Egyptian courtier who, for reasons unexplained, flees to Canaan upon the death of the pharaoh Amenemhet I, the first king of Dynasty 12 (1938–1908 BC).[18] Although prosperous in Canaan, Sinuhe later realizes the necessity of returning to Egypt to effect a reconciliation with the new king, Senusret I, and receive proper funerary rituals and burial rites on Egyptian soil. Sinuhe describes the natural environment of the area in which he lived—Canaan, Sinai, and the inhabitants of these lands—and provides perspective on the social organization and cultural traits of the Canaanites at his time. He describes the natural environment and fertility of Canaan: “It was a wonderful land called Yaa. There were cultivated figs in it and grapes, and more wine than water. Its honey was abundant, and its olive trees numerous. On its trees were all varieties of fruit. There were barley and emmer [wheat], and there was no end to all varieties of cattle (i.e., small livestock).”[19]

Game animals that were hunted in the “desert,” or wilderness areas, also comprised part of Sinuhe’s daily food. In addition to cultivation and herding, Sinuhe also acted as the commander of his patron’s forces, conducting raids against disruptive nomadic groups on the fringe of society and directing warfare against neighboring kingdoms.[20] Thus, within the story, we encounter diverse communities within Canaan, wherein a multifarious range of ethnicities interacted and integrated indigenous cultural and religious elements pertaining to their individual cultural identities found outside the boundaries of Canaan.

The Built Environment: Canaanite Centers

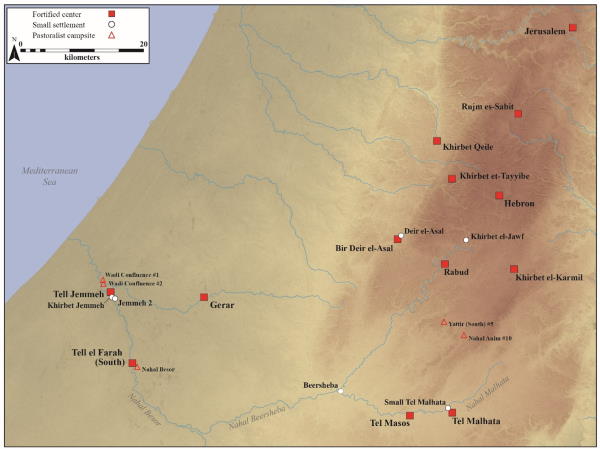

Middle Bronze Age sites are typically found along the margins of good soil types to maximize the amount of ground available for agriculture and are situated on natural hills with at least one good permanent source of water.[21] Such conditions led to the growth of urban centers with fortifications, religious precincts, and palatial architecture, and the preeminent sites of this period included Jerusalem, Shechem, and other locations discussed below (see figure 1). In addition to cities with massive fortifications complete with gates and ramparts, smaller unwalled villages and farmsteads were located in the countryside between larger urban centers. As Abraham journeyed southward from Haran into Canaan, he would have enjoyed a cooler climate with more precipitation and vegetation in which both established settlements and nomadic groups existed. As a pastoralist, he and his household would have been on the margins of Canaanite society, interacting with large, fortified centers and smaller hamlets when necessary but dwelling outside of the agricultural zones surrounding these sites in order to pasture the flocks. The fortified sites must have presented a visually formidable obstacle to the realization of the promise given to Abraham (and his descendants) by God regarding the possession of the land (Genesis 12:7, 15:7).

Figure 1. Middle Bronze Age Canaanite centers associated with the ancestral narratives. Map by the author.

Figure 1. Middle Bronze Age Canaanite centers associated with the ancestral narratives. Map by the author.

Although large portions of Middle Bronze Age cities have not been exposed by archaeology, the remains that have come to light, such as paved streets, public courtyards, and large palatial buildings with stone foundations, mud-brick walls, central courtyards, and plaster floors, exhibit a degree of town planning. However, while some streets followed straight lines, most residential areas grew organically with little thought for street layout, so lanes run along irregular lines with narrow passages and blind alleys.[22] The cyclical travels of the ancestors of Israel in Canaan brought Abraham and his descendants into contact with Canaanite cities, and a survey of these sites provides an understanding of the settlement picture during the ancestral age and the relationship between fortified urban centers and ephemeral sites associated with campsites and seminomadic activities.

Shechem

Abraham traveled from Haran in northern Mesopotamia to Hebron in Canaan via Shechem (spelled Sichem in Genesis 12:6) and Bethel likely using a route that followed the ridges of the central hill country of Canaan. Excavations at Shechem revealed multiple phases of Middle Bronze Age occupation, most with monumental architecture and large fortification walls.[23] In the eighteenth century, an earthen rampart was built to enclose the city surmounted by a mud-brick wall and was abutted by a series of courtyard and building complexes, part of which has been interpreted as a sacred precinct.[24] In the later phases of the Middle Bronze Age, a fortification wall of large boulders, called the “Cyclopean wall,” became part of the city’s defenses, and a large fortress-temple was first constructed. Although Abraham did not have much interaction with the site, Jacob purchased land from the territory of Shechem where he pitched his tent and built an altar for religious worship (Genesis 33:18–20). This landscape presents an interesting scenario of local Canaanite religious practices within the city of Shechem, as evinced by the large, archaeologically excavated temple and the personal religious experiences Jacob enjoys on the outskirts of town. Throughout the ancestral narratives, Abraham and his descendants are on the outskirts of Canaanite society yet have profound experiences with the divine away from such urban centers.

Bethel

The site of Bethel is mentioned once in connection with Abraham in which the patriarch built an altar between this site and Hai (‘Ai; Genesis 12:8) and was the site of Jacob’s dream, a reiteration of the Abrahamic covenant, and the construction of another altar (Genesis 28:10–22; 35:3–7). Originally named Luz by the Canaanites (Genesis 28:19), Bethel witnessed habitation since the Early Bronze Age when it served as a campground for shepherds before a permanent settlement was established.[25] During the Middle Bronze Age, some building activity occurred near the spring at the site with a fortification wall and gates in a subsequent phase of occupation. Inside the walled area of the city was a sanctuary marked by large quantities of animal bones and cultic vessels, although the precise dating for this sacred precinct is difficult since pottery vessels from multiple periods were found in excavations attesting to the persistence of cultic rituals in that location. Again, in contrast to the Canaanite religious worship in the city proper, the ancestors found religious significance with the God of Israel on the outskirts of town.

Hebron

Hebron and the plain of Mamre are recorded as places frequented by Abraham and Jacob (Genesis 13:18; 14:13; 18:1; 23:2, 19; 35:27), and as the location of the only parcel of the promised land that Abraham legally owned through purchase. In addition to a fortification wall, which has survived with a height of more than two meters faced with a stone rampart, excavations have also exposed a tower adjoined to the city wall.[26] Near this wall inside the city, fieldwork revealed a room with a great quantity of animal bones, ceramic sherds, and ash. Part of the debris from this room yielded a fragmentary cuneiform tablet that listed several animals and named four individuals.[27]

Philip Hammond, an excavator of Hebron, also found burial caves on the southeastern portion of the mound, one of which evinced a continuity of use from the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age I.[28] Such extensive use corresponds well with the use of the Cave of Machpelah as a burial place for the ancestors of Israel. Operating within the cultural norms, Abraham acquired the natural cave that would serve as the family tomb after Sarah’s death (Genesis 23:3–20).[29] The dialogue with Ephron the Hethite began with the polite rhetoric of offering Abraham the cave freely, which Abraham knew to refuse, and then ended with Abraham weighing out the four hundred shekels of silver to Ephron. No mention is made of a written land deed, but parallels from Mari and Emar in Syria suggest that Abraham received a tablet with the details of the transaction that was witnessed by both parties.

Canaanites in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages laid their dead to rest in various ways, and the deposition of the dead and the various accompanying grave goods inform us about Canaanite views on death and family.[30] In the Middle Bronze Age, the use of burial caves for an extended period of time indicates the desire of families to bury several generations of deceased family members together. A body would be laid out in the center of the cave, often on a wooden bed, and surrounding the deceased were various gifts consisting of storage jars with food or wine, containers for various other goods, weapons, and items of personal adornment.[31]

Alternatively used as the place-name for a cave and field (Genesis 23:9, 25:9; Genesis 49:30), the name Machpelah may have been derived from the Hebrew root kpl, meaning “double”; thus, the cave may have originally had two caverns suited for the burial of successive family generations.[32] Although the biblical text is silent on the details, Sarah may have been laid to rest with scarabs and other jewelry in addition to grave goods consisting of luxury items such as ivory inlaid boxes or ceramics containing oils or perfumes. When the cave was needed for later family members, her remains would have been moved aside to make way for the newly deceased. The continued use of the burial cave would have been seen as the family’s staking a claim on the property and renewing their rights of ownership.[33]

Additionally, archaeological surveys have recorded eight additional Middle Bronze Age sites within the region around Hebron. According to the surveyors, these sites were fortified during this period and located along routes through the hill country and the Shephelah.[34] Thus, Abraham and his progeny would not have wandered in a barren land devoid of settlement as they moved their flocks to different seasonal pastures. Rather, they probably moved from one site’s territory to another’s, using the fortified settlements and permanent water sources as waystations and trading posts.

Jerusalem

While the specific place-name Jerusalem does not appear as such in the ancestral narratives in Genesis, scholars have equated the Holy City with Salem, the city of the priest-king Melchizedek (Genesis 14:18; see also Alma 13:17–18).[35] This association is based on the clear link between Salem and the rendering of Jerusalem as (U)rusalimum in the Execration Texts.[36] Excavations at Jerusalem have revealed that the area around the southeastern spur of the Eastern Hill, or the City of David, was settled long before the Middle Bronze Age. In addition to the city wall and fort surmounting the southeastern spur,[37] additional fortified towers dubbed the Pool Tower and the Spring Tower were exposed near the Gihon Spring. Both towers were built using large boulders weighing 3–4 tons each. Construction efforts near the water source also included digging a large pool (16 x 10 m, 14 m deep) as a reservoir for water and digging channels to divert some of the water for irrigation in the Kidron Valley.[38] The complexity of the water system that included two large fortification towers, channels, a reservoir cut into bedrock, and the incorporation of natural fissures indicates a certain level of labor organization in Jerusalem during the Middle Bronze Age required for these construction efforts to have been completed and for the sole water source of the city to have been protected. Such may have been the setting of Abraham’s visit with Melchizedek (Genesis 14:17–20).

Moriah

Jerusalem has also been linked to the binding and near sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22. God instructed Abraham to go “into the land of Moriah; and offer him there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of” (Genesis 22:2). No further details are given about Moriah except that it was three days’ journey from Beersheba and that Abraham named the place “Jehovah-jireh” after the episode was complete (Genesis 22:3–4, 14). Moriah was equated with Jerusalem later when the Chronicler tied the land of Moriah/

Gerar

Both Abraham and Isaac lived in the region of Gerar during droughts, and both had encounters with a ruler, or successive rulers, in the area named Abimelech (Genesis 20:1, 26:6). Concerning Abraham’s activity in the region of Gerar and Beersheba, a place under the control of Gerar, the biblical record does not explicitly claim that he sacrificed in this area, but it is likely that he and Isaac both did so. Also, Abraham devoted some of his flock to establish a covenant with Abimelech. The fortifications at biblical Gerar in the western Negev date to the Middle Bronze Age and enclose an area of forty acres, making the site one of the largest in southern Canaan.[39] The site was surrounded by a defensive ditch and an earthen rampart with a stone facing. Within the fortifications, excavations encountered an extensive cultic complex consisting of a courtyard and various structures and installations. The remains of offerings, including sheep and goat bones (62 percent of the collection), were found throughout the complex and in favissae, pits dug to dispose of ritual offerings or votive items. Excavators uncovered a palace or large patrician house, and pottery imported from Cyprus attests the site’s prestige and commercial ties. Abimelech may have been a person of considerable relevance at the time, and a covenantal contract with Abraham seems to be reflected in religious relevance with the sacrifices offered between them. The favor Abraham gains in Abimelech’s sight seems significant given his kingly status.

Beersheba

No Middle Bronze Age remains were found in excavations of Tel Sheva, yet the excavator associated the well that had been dug near the gate of the site with the Abraham and Isaac traditions (Genesis 21:15; 26:25).[40] However, it can be seen that this theory is built on the faulty assumption that the well near the later Iron Age gate at Tel Sheva should be equated with the wells dug by Abraham and Isaac, although wells were usually dug closer to riverbeds to access groundwater during the Middle Bronze Age. Also, the location of any settlement called Beersheba during this ancestral period could be anywhere along the Nahal Beersheba and covered by alluvium from the seasonal stream, or the settlement’s location was so ephemeral that no traces of habitation would be visible. However, there are locations in this region that could have fit the narrative of the ancestral stories.

Figure 2. Middle Bronze Age fortified and unfortified settlements and campsites in the hill country and biblical Negev. Map by the author.

Figure 2. Middle Bronze Age fortified and unfortified settlements and campsites in the hill country and biblical Negev. Map by the author.

Settlement Patterns in the Negev

The sites discussed above are named within the Genesis accounts of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Additional sites in the Negev, unnamed in the biblical text but extant in the Middle Bronze Age, provide additional data about the experiences of Abraham and Isaac as they moved throughout the region (see figure 2). From west to east along the watercourses of the Nahal Besor, Nahal Beersheba, and Nahal Malhata, fortified centers and smaller sites that lack architecture in most cases testify to the nature of settlement along the southern frontier of Canaan. Two sites along the Nahal Besor are examples of sites with impermanent habitation.[41] In the absence of any trace of architecture, it is likely that these sites were campsites for nomadic or seminomadic groups that discarded broken items or left behind items that did not need to be transported to another site. In the region between Tel Masos and Hebron, an intensive survey was conducted around Horvat Yattir, and two Middle Bronze sites were likely satellites of a larger site yet to be discovered or were temporary settlements for seminomadic groups.[42] Inside the remains of an elliptical building made of fieldstones, a stone installation probably served as a hearth, and flint tools were found near the structure. It is possible that Isaac and Jacob may have lived in such structures during their extended habitation in the areas of Gerar or Shechem.

The permanent settlements were likely a chain of fortified sites comprising Tell el-Ajjul near the Mediterranean coast, Tell Jemmeh, Tell el-Farah (South), Tel Masos, and Tel Malhata. These fortified sites functioned not only as defensive sites but also as waystations for caravans from points south and east that headed overland to the Mediterranean ports or to Egypt via the Sinai.[43] Imported pottery from Cyprus at these sites suggests that they were connected to the larger Mediterranean exchange network of the Middle Bronze Age and were well situated on the overland route connecting Egypt and Canaan.[44] For most of these sites, smaller, less permanent satellite sites were found in close vicinity. These smaller sites lacking architecture may be considered campsites or areas where herds and flocks were kept and were dependent on the larger settlements for stable food and water supplies.[45] The ancestral narratives may have occurred in such settings as they traveled extensively across the region. Smaller structures may have also been used by those engaged in pastoral nomadism, or transhumance, as a temporary dwelling for those accompanying flocks to pasture areas, an example of “indigenous hardiness structures” in which people adapt to being sedentary or nomadic through a cycle of dwellings from buildings to caves to tents.[46] The archaeology of these sites provides a window into the seminomadic life of the Middle Bronze Age and may indicate the types of artifacts left behind by Abraham, Isaac, and their households as they moved from Hebron through the Negev to Beersheba, Gerar, Kadesh, and other sites in the western Negev.

Pastoral Elements of Near Eastern Society

It is clear from the accounts in Genesis that the ancestors focused much of their efforts on pastoral pursuits, although herding was only part of their group economy.[47] From the division of the livestock of Abraham and Lot (Genesis 13:5–12) to Jacob’s perception about flock watering (Genesis 29:1–10) and a perception about animal genetics (Genesis 30:41–42), the biblical record indicates that the ancestors of the Israelites were highly engaged with pastoralism. Transhumance, moving pastures seasonally with a herd or flock, is highlighted in the ancestral narratives once a stable base of operations was established, such as Isaac’s dwelling near Gerar or Jacob’s dwelling near Hebron.[48]

In the ancient Near East, both Palestine and most of northern Syria and Mesopotamia accommodated a mixed economy of pastoral nomadic and agricultural activity.[49] Environmental conditions in the hill country of Canaan and the Negev prompted the development of a society in which farmers and pastoralists would have had a natural symbiosis to better exploit the region’s limited natural resources.[50] However, local pastoralists who were living in villages and migratory pastoralists would have interacted and even come into conflict with each other. Grazing and water rights would have been shared between members of the same kinship group or their allies, prompting outside groups to move their flocks elsewhere in search of pastures without tribal claims.[51] Engaging in pastoralism mixed with other economic endeavors would have been considered the norm for marginal regions such as the hill country and Negev.

Faunal remains from archaeological excavations and ancient textual records illustrate the importance of pastoralism and pastoral products within the economy of Canaan. The age at death in the faunal remains at Canaanite sites indicates a primacy on dairy production.[52] Further, a cuneiform tablet found during excavations at Hebron records numbers of sheep, “small cattle,” and lambs collected by female tax collectors and mentions a king, possibly the king of Hebron.[53] Some of the sheep and goats may be described as “shorn,” indicating that wool and hair were collected from these animals prior to their transfer to the tax collectors.[54] Seventy-seven of the sheep or goats were destined for sacrifice or covenant rituals. This accords with the ancestral narratives in that pastoralists were an acknowledged component of Canaanite society and were valued for the products of their flocks and herds. It is also possible that Abraham and Isaac may have also been taxed in such materials in exchange for grazing rights.

The number of sheep and goat bones from pits and cultic contexts at biblical Gerar and Shechem show the importance of these animals in religious rites. The practice of slaughtering an animal in sealing a covenant was widespread in the Near East and attested in several texts. This portrays such rituals as witnessed between Abraham and the Lord (Genesis 15:8–17) and Abimelech (Genesis 21:22–34). A tablet found at the ancient site of Alalakh in Turkey relates the details of a covenant between an imperial vizier and a local ruler in which the local ruler received the city of Alalakh in exchange for another town destroyed in the process of suppressing a rebellion.[55] As part of the covenant ritual, the vizier “placed himself under oath to [the local ruler] and had cut the neck of a sheep (saying): ‘(Let me so die) if I take back that which I gave you.’”[56] The local ruler was required to maintain allegiance to his overlord lest he forfeit the territory granted to him. Among the twenty thousand cuneiform tablets found at the ancient site of Mari on the Euphrates River, several references are made concerning the establishment of covenants and the animals sacrificed.[57] Parallels between these rituals and the establishment of the covenant between Abraham and the Lord in Genesis 15:9–17, in which Abraham slaughters a young heifer, a she-goat, a dove, and a pigeon, are clear since these bisected animals represent the penalty if the covenant is forfeited.

Anthropological concepts of pastoralism, ancient texts, and the archaeological record illustrate the pastoral economies of the ancestors in the biblical record. Conflict between herding groups competing for resources is exemplified in Genesis 13:6, in which “the land was not able to bear them,” causing Abraham and Lot to separate and causing a reassurance of the covenant blessing of property given to Abraham (Genesis 13:14–17). Isaac is depicted engaging in both agriculture and pastoralism in the region of Gerar (Genesis 26:12, 14), but his group soon comes into conflict with the herders from the sedentary population over access to water, suggesting that the wells were nearer to grazing areas than the agricultural fields or urban center (Genesis 26:14–33). The seizure and defense of wells mentioned in the Tale of Sinuhe also finds parallels in the lives of Abraham and Isaac in the Negev (Genesis 21:25; 26:15, 20).[58] Yet it must be noted that the ancestors were not outcasts or shunned by society but were economically integrated into the larger economies of the Canaanite kingdoms by providing wool, hair, hides, dairy products, meat, and even live animals to the settled centers. As Matthews observes, “The patriarchal narratives simply point out to the reader how crucial the maintenance of good relations with the indigenous inhabitants of the land actually were.”[59]

The Ancestral Narratives as a Cognitive Map

Landscape is more than a flat backdrop for events through time or a container for actions. Equally, it is more than a playing board for a complex geopolitical chess game between historical figures, warring tribes, or conquering empires. Regardless of geographical or temporal location, every feature of landscape is enriched with people’s stories and beliefs, and these associated meanings give those places significance. A deeper investigation into the sites and regions associated with the ancestors of Israel gives possible insight into the collective consciousness of Israel as a people later in history. The ancestral narratives within the book of Genesis function as a cognitive map informing audiences, ancient and modern, about the places associated with these accounts.

The concept of a cognitive map, and its associated layers of meanings for locales and for guiding of actions, is employed by anthropologists intent on discovering the thought processes of ancient peoples. People navigate by landmarks—things that can be seen—and along paths, choosing the correct route whilst at a node, a connection, or intersection of paths. Because mental maps represent a shared worldview with other members of society and because those maps bind society together, they are part of a person’s cultural makeup.[60] Being able to construct a cognitive map requires composing a complex image of locations and their spatial relationship, drawing on layers of meaning for each locale.

Traditional homelands form part of the cultural reality of the cognized landscape, and multiperiod settlements hold spiritual and secular values.[61] It is the site from which the ancestors came and the place where the descendants will return. A sense of place is fundamental to the formation of biographies and the establishment of identities for groups and individuals.[62] This sense of place marks the fundamental concept underlying a reading of Genesis as a cognitive map for its Israelite audience. The ancestors sojourned and built altars to their deity throughout Canaan, the setting of their biographies as related in Genesis, and their chosen descendants are thereby entitled to inherit the land under the terms of the Abrahamic covenant (Genesis 12:7; 15:7, 18–21; 17:8, 22:7; 26:3; 28:13; 35:12).

A cognitive map is not simply an abstract coordinate system of the mind, but a setting loaded with historic references, mythic tales, and past experiences that bridge the gap between the physical and imagined landscape. This study should encourage a new reading of the text, seeking elements that would connect the Israelites with the ancestors and illuminate what the Israelites thought of certain locales. If naming a spot is an act of construction of landscape (constituting an origin point for it), then narratives make locales markers of individual and group experiences. Thus, the ancestral narratives function as a cognitive map, revealing the positive and negative feelings toward various sites and regions within the promised land. Places and movements of people are related to the formation of biographies, and places acquire layers of meaning as people interact with those places throughout time. The locales related in Genesis, such as Hebron, Machpelah, Beersheba, and Shechem, are stratified with the memories of the ancestors. A brief discussion of a few of these places allows one to see the values the Israelites would have associated with them.

In Genesis 13:17, God commanded Abraham to walk the length and breadth of the land promised to him; therefore, the place-names associated with his journeys would feature in the developing sense of place within the Israelites’ minds. Abraham’s rescue of Lot and the specific mention of Dan (Genesis 14:14) helped to give boundaries to the later Israelite territory, despite the anachronistic use of the place-name rather than its Canaanite name, Laish (Judges 18:29). Abraham’s treaty with Abimelech over watering rights led to the establishment of the “Well of the Oath,” or Beersheba (Genesis 21:22–33). Abraham was not the only patriarch to dwell at Beersheba, since Isaac also included Beersheba (Genesis 26:20–32), as well as Hebron (Genesis 35:27–28), Gerar (Genesis 26:1, 7), and Beer-lahai-roi (Genesis 24:62; 25:11), in his nomadic journeys, adding another layer of meaning and history to each place. Later, the prophet Amos (8:14) intimated that Beersheba was a place for pilgrimage and oracles. Taken together, two sites form the all-inclusive boundary for biblical Israel, “from Dan to Beersheba” (Judges 20:1; 2 Samuel 17:11, 24:2, 15; 1 Kings 4:25). Abraham’s presence at both sites allowed Israel to know that both sites fell within the land promised to them.

Landscape allows for an observer to investigate and organize reality in a particular way that may be different from others. The narratives surrounding Shechem are an example of the biblical authors having marked differences of opinion about Shechem. The picture of Shechem presented in Genesis is not pleasant. Except for God’s revelation to Abraham of the land grant and Abraham’s construction of an altar (Genesis 12:6–7), the exploits of Jacob’s children in Shechem were unfavorable. The incident between Dinah and Shechem, as well as the revenge taken by Simeon and Levi at the expense of the Shechemites, gave Jacob cause to fear the Canaanites. The honor of Jacob’s entire family was at stake, and Jacob’s response to his sons’ actions (Genesis 34:30) indicates that their recourse was less than honorable as well, even if it was culturally appropriate. Coupled with the actions of Jacob’s sons to sell Joseph into slavery in the Dothan region (Genesis 37:17ff), the impression given by the biblical author of the region of Shechem is one of wickedness and bloody revenge, both real and potential. Later, Abimelech, the son of Gideon, failed in his bid to become king during the period of the Judges, and emphasis is made in the story concerning the treachery of the men of Shechem (Judges 9). In a turn of events, Shechem became the first capital of the northern kingdom of Israel under Jeroboam following the division of the kingdom after Rehoboam, Solomon’s son, attempted to be recognized as king in Shechem (1 Kings 12:1, 25). Clearly, the role of a refuge city in Joshua 21 contrasts with the pictures of Shechem related in Genesis and Judges, and the perception of Shechem had changed from the powerful Canaanite kingdom to a wicked region during Jacob’s lifetime to a city of refuge during the early Israelite settlement to a treacherous city and rival to Jerusalem during the reign of the Judges and early years of the divided monarchy. Landscape archaeologist Christopher Tilley posits that landscape allows for “mnemonic pegs on which moral teachings hang,” and the moral lessons of Genesis 34 and 37 probably echoed in the minds of Israelites who knew the story well.[63]

Conclusion: Lessons from the Ancestors

Canaan was situated as a “land between” greater political powers of Egypt to the south and Syro-Mesopotamia to the north and east. Certain pottery forms and decoration, metal weapons, and imagery from seals show direct relations with Mesopotamia and northern Syria. Other cultural features such as fortification types, building techniques, architectural styles, burial customs, and artistic motifs appear to be derived from Amorite culture and subsequently shared across the Near East, with Canaan having some developments unique to itself in each of these areas. While some Egyptian texts focus on the destruction of Egypt’s enemies in Canaan and elsewhere, other evidence, such as tomb paintings and Egyptian artifacts found at Levantine sites, points to less hostile diplomatic and commercial interactions between Egyptians and Canaanites in the Middle Bronze Age, providing a context for the events of Genesis and the Book of Abraham. The same Egyptian tomb paintings also give a contemporary glimpse into the appearance and lifestyle of the Canaanite population, among whom the ancestors lived their seminomadic existence while leaving little archaeological evidence behind regarding their pastoral pursuits. Canaan as the “land between” the powers of Mesopotamia and Egypt was the stage for the ancestral narratives following the obedience of Abraham to the covenant call to leave his family group in Haran and sojourn in a land that the Lord would show to Abraham.

Urban theorist Kevin A. Lynch wrote that “striking landscape is the skeleton upon which many primitive races erect their socially important myths.”[64] While one would hesitate to call the ancestral narratives myths from a primitive race, the importance of landscape, both physical and mental, is evident. Although this paper only treated a few of the place-names mentioned in the Genesis text, the ancestral activity at each place tied their descendants to the land. The future Israelites, upon establishing themselves in Canaan, could hardly look to Shechem and not think of Dinah or look to Beersheba and not be mindful of the sheep and watering rights secured by Abraham and Isaac with the local polity. Hebron, with its affiliation as Abraham’s home and the ancestral burial place, bears great significance. The conquest narratives end after Kiriath-arba (Hebron) is apportioned to Caleb, thus securing the family burial ground as part of the birthright inheritance of Judah (Joshua 14.15). Only then could the land have rest from war, and only then could the Israelites begin the tasks associated with subsistence and establishment of civil order. With each passing generation since Abraham, the ancestors and their offspring added more and more meaning to the locales.

The stories of ancestors of Israel, their subsistence in Canaan, and their interactions with the local populace provided and continue to provide valuable lessons for the audiences of Genesis. Part of Abraham’s test of faith is placing him in a land where he needs to rely on divine providence. He was not placed in a land empty of inhabitants and replete with natural resources and easy conditions for success. Abraham and his descendants, through Jacob and his sons, would effectively be resident aliens on the margins of society in the land promised to them by divine covenant. Part of the test of faith for Abraham and his family involved them looking to God for protection and fulfillment of the covenantal blessings rather than relying on their own intuition, cunning, adept political maneuvering when negotiating pastoral rights, or the strength of the fortified centers with which they interacted. Even the wayward Egyptian Sinuhe noted that “God acts in such a way to be merciful to one . . . whom He led astray to another land.”[65] The message for the modern reader is clear: in assessing one’s faith, God places one in circumstances that will necessitate a decision to look to him for guidance and providence or to rely on the arm of flesh—the perceived strength of the world. Hebrews 11:8–10 relates that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob hearkened to their divine calls and lived lives of faith, thus providing the example of faithful living to the house of Israel and all the nations of the earth who are and will be blessed through Abraham and his seed.

Notes

[1] Despite the biblical text using the name “Abram” from Genesis 11:27–17:5, the name “Abraham” is used within this paper for this ancestor of Israel due to its familiarity for the reader. This is not to downplay the significance of the name changes for Abram and Sarai by divine decree in Genesis 17.

[2] The order of events related in Abraham 2 are slightly reversed, in that the Lord first caused a famine and then called Abraham to leave Ur and go to a land that God would show to Abraham, after which his family travels to Haran (Abraham 2:1–4).

[3] The date of Abraham’s birth as discussed by scholars in the twentieth century ranges between 2100 and 1800 BC. Assuming the years for lifespans in the biblical text as literal and accurate and adhering to the lower date, the scholar and archaeologist William F. Albright surmised that Abraham lived well into the eighteenth century BC, which would place the death of Jacob near the end of the sixteenth century and situate the ancestors within the Middle Bronze Age and the transition to the Late Bronze Age. William F. Albright, “From the Patriarchs to Moses: From Abraham to Joseph,” Biblical Archaeologist 36 (1973): 16. While modern scholars have dismissed the historical veracity of the ancestral narratives and early attempts to situate them within a historical period, some biblical scholars now view these passages as cultural memories that include traditions that predate major biblical authors and the formation of Israel but do include some editorial updating for their intended ancient audience. Ronald S. Hendel, Remembering Abraham: Culture, Memory, and History in the Hebrew Bible (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 45–47.

[4] Alan R. Millard, “Methods of Studying the Patriarchal Narratives as Ancient Texts,” in Essays on the Patriarchal Narratives, ed. A. R. Millard and D. J. Wiseman (Leicester, UK: InterVarsity Press, 1980), 45.

[5] Concerning the use of ancient texts as data sources, surviving Canaanite material from the Middle Bronze Age is scarce, and many of the textual sources are presented from an elite or royal perspective and lack individuality. To mitigate these textual problems, a familiarity with the regional settlement history and material culture gained from the archaeological record aids in appreciating the lifeways of the Canaanites while ancient, extrabiblical texts play a supporting, albeit important, role in illuminating certain cultural aspects of the period. Ancient Near Eastern texts from Egypt and various Syrian and Mesopotamian cities like Nuzi, Mari, Emar, and Alalakh do not provide direct parallels but illustrate that the ancestral narratives reflect common practices of the Near East in the second millennium BC. See Bill T. Arnold and Bryan E. Beyer, Readings from the Ancient Near East: Primary Sources for Old Testament Study (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2002), 72; John H. Walton, Ancient Israelite Literature in Its Cultural Context (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1989), 49–58.

[6] David Ilan, “The Dawn of Internationalism: The Middle Bronze Age,” in The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, ed. T. E. Levy (London: Leicester University Press, 1995), 297.

[7] Ram Gophna, “Early Bronze Age Canaan: Some Spatial and Demographic Observations,” in Levy, Archaeology of Society, 269.

[8] Site catchment analysis, soil quality (or potential), archaeobotany, pollen and mollusk studies, geomorphology, and archaeozoology all contribute to an overall perception of the paleoenvironment. See Kevin Walsh, “Mediterranean Landscape Archaeology and Environmental Reconstruction,” in Environmental Reconstruction in Mediterranean Landscape Archaeology, ed. P. Leveau et al. (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1999), 1–3.

[9] Raymond S. Bradley, Paleoclimatology: Reconstructing Climates of the Quaternary (San Diego: Academic Press, 1999), 5.

[10] Fatima F. Abrantes et al., “Paleoclimate Variability in the Mediterranean Region,” in The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From Past to Future, ed. Piero Lionello (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2012), 4–17.

[11] Peter B. de Menocal, “Cultural Responses to Climate Change during the Late Holocene,” Science 292 (2001): 670.

[12] Arie S. Issar and Mattanyah Zohar, Climate Change—Environment and History of the Near East (Berlin: Springer, 2007), 135.

[13] Arie S. Issar, Climate Changes during the Holocene and Their Impact on Hydrological Systems (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 21; Issar and Zohar, Climate Change, 150. Stable isotope analysis of speleothems in the Soreq Cave provides substantiation for a drier climate after 2000 BC; see Miriam Bar-Matthews, Avner Ayalon, and Aaron Kaufman, “Late Quaternary Paleoclimate in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from Stable Isotope Analysis of Speleothems at Soreq Cave, Israel,” Quaternary Research 47 (1997): 155–68.

[14] William F. Albright, The Archaeology of Palestine (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1960); Albright, “Abraham the Hebrew: A New Archaeological Interpretation,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 163 (1961): 36–54; Kathleen Kenyon, Amorites and Canaanites (London: Oxford University Press, 1966); William G. Dever, “The Beginning of the Middle Bronze Age in Palestine,” in Magnalia Dei, The Mighty Acts of God: Essays on the Bible and Archaeology in Memory of G. Ernest Wright, ed. F. M. Cross, W. E. Lemke, and P. D. Miller (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1976), 3–38.

[15] Kurt Sethe, Die Ächtung feindlicher Fürsten, Volker, und Dinge auf altägyptischen Tongefäßcherben des Mittleren Reiches (Berlin: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaft, 1926); Georges Posener, Princes et Pays d’Asie et de Nubie: Textes Hiératiques sur des Figurines d’Envoûtement du Moyen Empire (Brussels: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 1940); Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem: Carta, 2006), 100–102.

[16] Moshe Anbar and Nadav Na’aman, “An Account Tablet of Sheep from Ancient Hebron,” Tel Aviv 13–14 (1986): 3–12.

[17] Aaron A. Burke, “Entanglement, the Amorite koiné, and Amorite Cultures in the Levant,” ARAM 26 (2014): 360–62.

[18] Explaining the reason for his flight later to a Canaanite ruler, Sinuhe states, “I do not know what brought me to this land. It was like the plan of a god.” William K. Simpson, ed., The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003): 54–66.

[19] Simpson, Literature of Ancient Egypt, 58.

[20] Anson F. Rainey, “The World of Sinuhe,” Israel Oriental Studies 2 (1972): 378–79. Rainey interpreted these aspects of Sinuhe’s activities in Canaan, together with the organization needed to conduct horticulture and pastoral endeavors and the mention of Sinuhe entertaining Egyptian dignitaries, as signs that the land of Sinuhe’s sojourn was a developed society with elements of settled and nomadic groups. Interestingly, the Book of Abraham also describes Egyptianized societies among whom Abraham lived.

[21] For a discussion of this settlement pattern in the western Galilee during the Middle Bronze Age, see Assaf Yasur-Landau, Eric H. Cline, and George A. Pierce, “Middle Bronze Age Settlement Patterns in the Western Galilee, Israel,” Journal of Field Archaeology 33 (2008): 59–83. This provides the backdrop for farming and the raising of cattle in the Isaac and Jacob stories.

[22] Sites with Middle Bronze Age palaces reveal that the palace of the city was usually located close to a temple. Palaces were decorated with orthostats, large stones placed along the bottom of a wall for support and decoration. Both the use of orthostats and the general layout and characteristics of Middle Bronze Age palaces in Canaan show direct influence from larger Syrian palaces that predate those in Canaan, again showing shared culture thought to be Amorite in origin.

[23] Edward F. Campbell, “Shechem: Tell Balâtah,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, ed. Ephraim Stern (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 4:1347; see also G. Ernest Wright, Shechem: The Biography of a Biblical City (New York: Doubleday, 1965); Dan P. Cole, Shechem I: The Middle Bronze IIB Pottery (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1984).

[24] Campbell, “Shechem,” 1349.

[25] James L. Kelso, The Excavation of Bethel (1934–1960) (Cambridge: American Schools of Oriental Research, 1968); James L. Kelso, “Bethel,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 1:193.

[26] Avi Ofer, “Hebron,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 2:608.

[27] Anbar and Na’aman, “An Account Tablet of Sheep”; a bulla (a lump of clay used to seal documents, jars, or rooms) bearing an Egyptian scarab impression was also found in the room, and a socketed ax head was found in an adjacent room. Both items could be indicators that the resident was of high status within Canaanite society.

[28] Ofer, “Hebron,” 608.

[29] Joseph A. Callaway, “Burials in Ancient Palestine: From the Stone Age to Abraham,” Biblical Archaeologist 26 (1963): 90.

[30] Rachel S. Hallote, “Real and Ideal Identities in Middle Bronze Age Tombs,” Near Eastern Archaeology 65 (2002): 105–11.

[31] Kenyon, Amorites and Canaanites, 74–76; The presence of individual graves for persons who were buried with spears, daggers, and bronze belts as well as accompanying equid burials in Syria, Canaan, and the Nile Delta led scholars to associate these “warrior burials” with a common Amorite background.

[32] Victor P. Hamilton, The Book of Genesis: Chapters 18–50 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 125.

[33] Hallote, “Real and Ideal Identities,” 109.

[34] Moshe Kochavi, “The Land of Judah,” in Judaea, Samaria, and the Golan: Archaeological Survey, 1967–1968, ed. Moshe Kochavi (Jerusalem: Carta and Archaeological Survey of Israel, 1972), 20.

[35] William F. Albright discounted the association between Salem and Jerusalem and emended the text of Genesis 14:18 to read, “And Melchizedek, a king allied to him [Abram] brought out bread and wine,” removing any association between Melchizedek and Jerusalem and Abraham and Jerusalem. Driving this emendation was Albright’s understanding of the archaeology of Jerusalem current with his time. See Albright, “Abraham the Hebrew,” 52.

[36] Rainey, “World of Sinuhe,” 407.

[37] This fortress is most likely the “stronghold of Zion” captured by David in 2 Samuel 5:6–9.

[38] Ronny Reich and Eli Shukron, “Jerusalem: Excavations within the Ancient City, the Gihon Spring and Eastern Slope of the City of David,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 5:1801–1805.

[39] Eliezer D. Oren, “Haror, Tel,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 2:580.

[40] Yohanan Aharoni, “Nothing Early and Nothing Late: Re-Writing Israel’s Conquest,” Biblical Archaeologist 39 (1976): 63.

[41] Amnon Gat, Archaeological Survey of Israel: Map of Nirim (112) (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2012), sites 13 and 14.

[42] Yattir (South) and Nahal Anim; see Ya‘akov Baumgarten and Hillel Silberklang, Archaeological Survey of Israel: Map of Yattir (136) (Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2015), sites 165 and 229; Hanan Eshel, Jodi Magness, and Eli Shenhav, “Yattir, Khirbet,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 5:2069.

[43] Archaeological data suggests that the following sites were occupied and fortified during the same period: Tell Jemmeh (Gat, Map of Nirim, Site 10; Jerome Schaefer, “The Ecology of Empires: An Archaeological Approach to the Byzantine Communities of the Negev Desert” [PhD diss., University of Arizona, 1979]; Gus W. Van Beek, “Jemmeh, Tell,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 2:667–74); Tell el-Far’ah (South) (W. M. F. Petrie, ed., Beth-Pelet I (Tell Fara) [London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, 1930]; Yigael Yisraeli, “Far’ah, Tell el- (South),” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 2:441–44; Dan Gazit, Archaeological Survey of Israel: Map of Urim (125) [Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 1996]); Tel Masos (Volkmar Fritz and Aharon Kempinski, eds., Ergebnisse der Ausgrabungen auf der Hirbet el-Msas (Tel Masos), 1972–1975 [Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1983]; Aharon Kempinski, “Masos, Tel,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 3: 986–989); and Tel Malhata (Ruth Amiran and Carmela Arnon, “Notes and News: Small Tel Malhata,” Israel Exploration Journal 29 [1979]: 255–56; Ruth Amiran and Ornit Ilan, “Malhata, Tel (Small),” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 3:937–39; Moshe Kochavi, “Malhata, Tel,” in Stern, New Encyclopedia, 3:934–36).

[44] Celia Bergoffen, “Imported Cypriot and Mycenaean Wares and Derivative Wares,” in The Smithsonian Institution Excavation at Tell Jemmeh, Israel, 1970–1990, ed. Gus W. Van Beek and David Ben-Shlomo (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2014), 657–61; David Ben-Shlomo, “Synthesis and Conclusions: The Significance of Tell Jemmeh,” in Van Beek and Ben-Shlomo, Tell Jemmeh, 1054.

[45] Nelson Glueck, “The Age of Abraham in the Negeb,” Biblical Archaeologist 18 (1955): 4.

[46] Øystein LaBianca, Hesban 1, Sedentarization and Nomadization: Food System Cycles at Hesban and Vicinity in Transjordan (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1992).

[47] Victor H. Matthews, “Pastoralists and Patriarchs,” Biblical Archaeologist 44 (1981): 215. Additionally, Albright argued that Abraham was a donkey caravaneer in the nineteenth century BC based on an understanding that verbs stemming from the root sḥr meaning “to trade (in), trader” applied directly to Abraham (Genesis 23:16) and later Jacob and his sons (Genesis 34:10, 21; 37:28; 42:34). See Albright, “Abraham the Hebrew,” 44–52; Albright, “From the Patriarchs to Moses,” 12. However, applying this term to Abraham and his descendants based on these scriptural references is problematic because the verses do not directly refer to activities conducted by the ancestors. In Genesis 23:16, the passage refers to the weighing of silver according to the merchant standards of the day as Abraham purchased the Cave of Machpelah from Ephron the Hethite without clearly stating that Abraham or Ephron were merchants: “Abraham weighed to Ephron the silver, which he had named in the audience of the sons of Heth, four hundred shekels of silver, current money with the merchant” (italics in KJV). In the later uses, E. A. Speiser preferred to interpret the forms of sḥr as “to move about (freely)” so that both Genesis 34:10, 21 and Genesis 37:28 can be seen as encouragements from the ruler of Shechem to the household of Jacob to stay within the territory of Shechem with the understanding that as pastoral nomads, Jacob and his family would interact with the members of the settled population and provide products such as wool, hair, milk, other dairy products, and even animals for cultic practices. Ephraim A. Speiser, Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes (New York: Doubleday, 1964). The final occurrence in Genesis 42:34 would also draw in this meaning of free movement as Joseph instructs his brothers to return to Egypt with Benjamin to secure safe travel in the land.

[48] Matthews, “Pastoralists and Patriarchs,” 217.

[49] Pastoralism is an adaptation to environmental and political conditions and is an economic mode of production not indicative or exclusively tied to a permanent habitation within a region. Victor H. Matthews, “The Wells of Gerar,” Biblical Archaeologist 49 (1986): 119.

[50] Michael B. Rowton, “Dimorphic Structure and Topology,” Oriens Antiquus 15 (1976): 20.

[51] Matthews, “The Wells of Gerar,” 121.

[52] Edward Maher, “Temporal Trends in Animal Exploitation: Faunal Analysis from Tell Jemmeh,” in Van Beek and Shlomo, Tell Jemmeh, 1038–53.

[53] Anbar and Na’aman, “An Account Tablet of Sheep,” 10–11.

[54] Wayne Horowitz and Takayoshi Oshima, Cuneiform in Canaan: Cuneiform Sources from the Land of Israel in Ancient Times (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 2006), 90.

[55] Donald J. Wiseman, The Alalakh Tablets (London: The British Museum, 1953), AT 1 and AT 456.

[56] Donald J. Wiseman, “Abban and Alalah,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 12 (1958): 129.

[57] Moshe Held, “Philological Notes on the Mari Covenant Rituals,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 200 (1970): 33, 40.

[58] Simpson, Literature of Ancient Egypt, 59.

[59] Matthews, “The Wells of Gerar,” 124.

[60] John J. Chiodo, “Improving the Cognitive Development of Students’ Mental Maps of the World,” Journal of Geography 96 (1997): 154.

[61] Ezra B. W. Zubrow, “Knowledge Representation and Archaeology: A Cognitive Example Using GIS,” in The Ancient Mind: Elements of Cognitive Archaeology, ed. Colin Renfrew and E. B. W. Zubrow (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 112.

[62] Christopher Tilley, A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths, and Monuments (Oxford: Berg, 1994), 18.

[63] Tilley, Phenomenology of Landscape, 33.

[64] Kevin A. Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, 1960), 4.

[65] Simpson, Literature of Ancient Egypt, 60.