Sidney B. Sperry: Seeking to Know the Word

V. Wallace McCarlie and Andrew C. Skinner

V. Wallace McCarlie Jr and Andrew C. Skinner, “Sidney B. Sperry: Seeking to Know the Word,” in Covenant of Compassion: Caring for the Marginalized and Disadvantaged in the Old Testament, ed. Avram R. Shannon, Gaye Strathearn, George A Pierce, and Joshua M. Sears (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 1‒28.

V. Wallace McCarlie Jr. is director of the Division of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics and an associate professor at East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina.

Andrew C. Skinner is a professor emeritus of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Marking the fiftieth anniversary of the annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium, this essay describes in part the man for whom the symposium is named and whom it honors. His life story, which has remained relatively unknown, provides many lessons applicable to Latter-day Saint religious scholars today. Herein we trace some of what he did to become the first person in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to receive a PhD in the field of ancient languages and civilizations of the Near East.

The adolescent Sidney B. Sperry, in a sacred moment with his grandfather, an ordained patriarch, was promised in the name of the Lord that he would “have the privilege of going forth into the world to lift up [his] voice in defense of Zion.”[1] That day, young Sidney learned he had “pled with the Father” in the premortal realm to “take an active part in the great work of God in the Latter-days.”[2] Patriarch Sperry also promised him that he would have the privilege of teaching the word of God to many, many people.

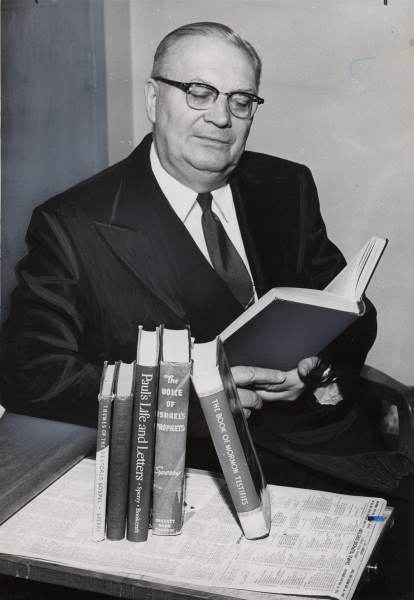

Sidney B. Sperry, courtesy of the Religious Studies Center.

Sidney B. Sperry, courtesy of the Religious Studies Center.

Before World War I, with a degree in chemistry, Sidney had dreamed of pursuing a PhD in chemistry in Berlin. After serving in the war, however, his feelings understandably changed. Upon his return, he was called as a missionary to the Southern States Mission (1919–21), where he was chosen to serve as the equivalent of district president; he served in this calling for most of his mission. Early in his mission experience, Sidney had not necessarily chosen his life’s path, but he had nevertheless entered upon it. He would become an active teacher of God’s word for the remainder of his life—the next six decades. He would teach in seminaries and institutes for nine years and at Brigham Young University for the next five decades. Sidney had aspired early on, probably before his mission, “to know more about the scriptures than any man living.”[3]

Adam S. Bennion, superintendent of Church schools, played a key role in recruiting Sidney. Bennion “sought to employ only the very best teachers and . . . required that all instructors be morally clean, obey the Word of Wisdom, and live their religion. He particularly sought out teachers ‘whose spiritual glow’ would ‘enkindle religious enthusiasm on the part of those instructed.’”[4] In inviting Brother Sperry to consider teaching in the Church school system, Brother Bennion did not need to twist Sidney’s arm. A desire to teach God’s word had grown within him. It is clear that Sidney wanted to pursue a doctorate, but he now had family responsibilities since he had married Eva L. Braithwaite on September 1, 1921. A position in the Church school system offered him a chance to formally begin his life’s work as a gospel teacher. Sperry responded to the need for faithful teachers in the system. Bennion’s offer apparently came in 1921, and Sperry began teaching in 1922.

One thing Brother Sperry observed upon entering the seminary system is that its three-year theology curriculum lacked a specific course on the Book of Mormon.[5] He joined in expressing the need for greater focus on the Book of Mormon, gospel scholarship, and the nurturing of faith. As principal of American Fork Seminary, he, along with his colleague at Pleasant Grove Seminary, articulated this desire in a letter to the president of Brigham Young University (BYU): “There is a great opportunity and need at the present time to vitalize and illustrate the teachings of the restored gospel.”[6] The letter continued, “Many valuable faith promoting incidents and manifestations have failed to be recorded where they are available,” appealing to President Franklin S. Harris’s “desire to promote the faith of the youth of Zion.”[7] Brother Sperry went on to say that with the approval of the Church Commissioner of Education, John A. Widtsoe, the seminary teachers were asking for written accounts of the most faith-promoting incidents in Latter-day Saints’ lives in every stake and mission throughout the Church. The goal was to publish these accounts and integrate them into the curriculum.

In a 1924 Church school system conference that Sperry attended, Bennion acknowledged what Sperry had observed—teachers were generally “slighting” the Book of Mormon. The conference produced a clearer vision of what Sperry thought should happen: “I am particularly anxious that . . . we shall cultivate genuine appreciation of and a love for the Book of Mormon on the part of our young men and women,” and that “no book should be better known by our students . . . than the Book of Mormon.”[8] The leaders now wished the Book of Mormon to serve a more prominent role in building the faith of the rising generation. Brother Sperry had applied these principles in his own classes and was glad to see these policies move forward.

Since the First Vision, none of those who had accepted the Prophet Joseph Smith’s message had earned a PhD in the field of ancient Near Eastern studies. Before entering American Fork Seminary’s doors as principal in the fall of 1922, Sperry had already begun his graduate coursework in history, political science, education, and psychology in pursuit of his advanced degree, having matriculated as a graduate student at BYU that summer. He may have received guidance that this graduate work would serve as a springboard for him. The tuition was also relatively inexpensive in comparison to more robust academic institutions. He continued with this plan during the summers of 1923 and 1924, taking further courses in history, physics, the philosophy of education, and education administration. Later, however, because of the caliber of scholarship at more established universities, he lamented his decision: “I’m almost sorry I ever went to the B.Y.U.”[9] Still, by 1924, Sperry knew a little more French, thanks to his work in Provo.

Sperry was well-liked among his colleagues and regarded as one who spoke having authority. On April 23, 1923, Elder James E. Talmage ordained him a high priest, and he was called to the high council in the American Fork Stake. Elder Talmage confided in Brother Sperry that a number of the General Authorities thought the Church should have among its ranks a scriptural scholar, a theologian who could stand up to the world in defense of Zion. Elder Talmage and others trusted Sperry and thought he possessed the ability to succeed. After his summer graduate courses in 1924, Sperry was asked to establish the seminary program at Weber College, in Ogden, Utah, that fall. He would miss his associates at the American Fork Seminary and his association with the stake presidency in his ecclesiastical calling, but he would now serve as Weber’s principal. The academic year of 1924–25 was a crucial time in Sperry’s life, as he decided BYU would not help him in his goal of becoming a PhD-holding scriptural scholar among the Saints. His decision would significantly affect the Church school system, BYU, and the Church. It would take faith and sacrifice as Sperry left Utah and his family. As his time at Weber came to a close, the leaders and students expressed gratitude for the teacher he had been and for the truths he had taught.[10]

From the main areas settled by Latter-day Saints, especially in Utah, those Saints pursuing doctoral degrees specializing in fields other than Near Eastern scriptural studies tended to go either westward to the University of California at Berkeley or eastward to the University of Chicago.[11] Besides Chicago in the Midwest, graduate students tended to go to Cornell in the East, with a few attending Harvard, Columbia, or the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The most popular institutions for graduate study other than Berkeley in the West included the University of California at Riverside and, in fewer cases, Stanford.[12] But Sidney did not have prior precedent to rely on as he embarked on his novel enterprise. Thoughtfully, Sperry did his best to decide where to go, noting that the Divinity School at Chicago stood out above other options. Harvard’s Divinity School was not yet in full ascent, Union Theological Seminary would have been costlier, and neither Cornell nor the University of Wisconsin had full-fledged divinity schools. None of the westward universities had full-fledged divinity schools either nor was the religious education at the level of what Sidney perceived Chicago’s standard to be. In the end, Sperry chose Chicago because of its standard of scholarship. In Sperry’s own words, privately shared with Eva, he wrote of someone considering following his footsteps: “He will sure be foolish if he ever goes to California,” signaling Sperry’s preference for Chicago.[13]

Sperry knew the University of Chicago was considered a metropolis of learning during the 1920s. Besides boasting the University, the city was deemed a cultural and social mecca in which the arts and sciences flourished. Chicago’s citizenry was high-minded about its city and university, and for good reason. In just 25 years, the University of Chicago had reached a scholarly pinnacle and built an infrastructure that other great universities had only attained after 250 years, and this intellectual and physical growth had “probably never been equaled in the history of learning.”[14] Sidney B. Sperry entered the University of Chicago in 1925 on the heels of this growth, in a time when the future medical school’s plans had been approved, a theology building was under construction, and plans for the Divinity Chapel were moving forward.[15]

That same year Chicago’s president wrote of the University’s Divinity School: “The list of books which have been written or edited by the members of the faculty is a very long one, possibly surpassing that of any other theological faculty in the country.”[16] The president was not presumptuous in saying such things, for the Divinity School housed some of the most illustrious and able scriptural and ancient Near East scholars of the time. The distinguished Belgian scholar Franz Caumont, for example, indicated that James Henry Breasted’s 1924 published account of a singular discovery illuminating ancient Syria “can hardly be exaggerated” and “throws vivid light upon numerous questions.”[17] Indeed, among Chicago’s professors with whom Sperry would study closely were some of the most erudite scholars in the United States and in the world. Martin Sprengling, for instance, had mastered “a dozen languages, eastern and western, [which] were his ‘open sesame’ to the storehouse of the history and culture of the Mediterranean world and particularly to the mainsprings of Near Eastern thought and patterns of life.”[18]

The year Sperry arrived, one of Chicago’s newspapers published a piece entitled “Chicago and Its Universities,” revealing the milieu in which Sperry had entered. It exulted: “Chicago is no city which sits at the nation’s gate to take toll. It buys and sells, but, more important, it creates. It is a mighty workshop. To it flock the young men and women who are to inherit leadership of the empire of which Chicago is the capital. Here they are trained in the professions, in the arts, and in the sciences. . . . The middle west knows only one aristocracy: the aristocracy of competence. No standard of scholarship which these new professional schools may maintain can be too exacting. The middle west, and Chicago in particular, needs the best youth with the best training.”[19]

This move to Chicago entailed serious sacrifice on the family’s part, but especially on Eva’s. On June 15, 1925, Sperry boarded the train in Salt Lake City en route to Chicago after Eva and Lyman (“buddy,”[20] as Sidney called him), who was born almost two years before, moved to Manti, Utah, where Eva’s widowed father, Robert Braithwaite Jr., would accommodate both his daughter and grandson. Just a month and a half removed from their separation, the reality of the moment was setting in for Eva. Without her husband, she would shoulder the weight of the family basically alone, and she was eight months pregnant with their second child.[21] To be back with her father, who was fifty-eight years old, and to know that she would not likely see or be with Sid for more than a year was almost too much to bear. Over the last four years, in support of her husband’s spiritual goals, which she had adopted as her own, she felt ping-ponged, moving four times. Sidney tried to encourage her while also revealing his profound feelings about Chicago: “Be brave and use all your will power to come thru. You will be alright and after a while maybe we can settle down permanently and raise our family. I’ve not regretted choosing Chicago as my school. It certainly is wonderful and interesting as well. Believe me I ought to know something about the Bible if my plans go right. So cheer up dear.”[22]

Sidney’s goal of knowing more about the scriptures than any earthly person continued. In Chicago, he was riveted on his scriptural studies. “How the time has flown! I suppose it flies so fast because nearly every minute of my time is taken in listening to lectures and studying.”[23] He regretted nothing about Chicago except that Eva and Lyman were not with him. To Eva, he confided: “There is a wonderful class of men to teach here. They sure know their stuff. Glad I came.”[24] Together his four professors that quarter combined for ninety-four years of teaching experience. Three were full professors, and they had all been educated at major centers of learning, including Berlin, Oxford, Yale, and Chicago. All were exacting in their specialty areas of Hebrew, Greek, New Testament and early Christian literature, the history and civilization of the Near East, and Isaiah. For Sperry, it was an exhilarating quarter of learning under these professors, including John Merlin Powis Smith, who at the time had been the editor of the American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures for seventeen years running.[25]

As his scriptural studies continued, the same theme of constant study continued: “This is Sunday and I am here in my room studying,”[26] and a few weeks later when writing Eva, he mused: “As time flies so fast when studying I thought it best to write you before it gets too late. We have so much to do that it takes about all the time we can get to get our work done.”[27] Though Sperry’s load was a grind, and it was a great sacrifice to be separated, he wanted Eva to feel that her sacrifice was not in vain and to feel his deep love for her: “Well I hope our plans work out alright and I believe they will. It will pay us to sacrifice a year or two [to start off] much as we hate to. . . . Would have a hard time telling you how much I love you though. Cheer up and tell me soon that there is another buddy boy or girl in the family and that you are all right.”[28] As it turned out, the next day their second child and first daughter, Claire Elaine Sperry, was born in Manti, Sanpete County, Utah. Eva’s Western Union Telegram to Sidney a day later read, “Nine pound baby girl nine thirty yesterday doing fine Love Eva 1225P.”[29]

Though most of Sperry’s intellectual experiences at Chicago were focused on scriptural studies, his scientific background as a chemist and his knowledge in mathematics led colleagues in other disciplines to bring him into their intellectual discussions. One such occasion prevented Sperry, as he penned later, from writing Eva because he was “invited to a supper by a group of men who were anxious for me to join their conversation. We were talked to after supper by a world-famous mathematician, Dr. Lunn, who talked about the theory of relativity as applied to practical affairs.”[30] A member of the National Academy of Sciences and an energetic teacher, Arthur Constant Lunn was a full professor in Chicago’s mathematics department, arguably one of the three most prestigious mathematics departments in the United States at the time—the other two being Harvard and Princeton. Lunn was an impressive genius who had a great impact on a number of world-renowned scientists through his teaching and work.[31] Sperry must have been invigorated with Lunn, who “integrated everything into one gorgeous whole.”[32] As Sperry came to the conclusion of this intellectually demanding and enthralling summer quarter, he confided to Eva, “Have been having exams today and have three tomorrow. It is pretty late now and I ought to be in bed. . . . Tomorrow ends school and I am rather glad because it surely has been a grind.”[33]

That fall, the theme of challenging intellectual work in his scriptural studies had not changed. If anything, it had become increasingly arduous. Running at full capacity, he wrote Eva, “The time goes so fast that I can’t keep track of the date. There ought to be more hours in the day. It seems like there isn’t time to accomplish what one would like to.”[34] Later he explained one reason why: “My course is very stiff here mainly on account of Hebrew. Not a single student that started with me has continued, and consequently I had to get into a class where students have had a lot of Hebrew. There are but four in the class at that. The Egyptian is bad enough too.”[35] Despite the strain, Sperry noted privately to Eva that his professors were taking note of his work ethic and especially his ability to learn ancient languages, both Hebrew and Egyptian. Noting Sperry’s talent in his Egyptian course, T. George Allen, a foremost expert of Egyptian funerary literature, encouraged Sidney, telling him that the universities throughout the nation needed people like him to specialize in Egyptology.[36] This encouragement led Sidney to quip to Eva, “You may see a great deal of the U.S. yet.”[37]

Meanwhile, Eva’s feelings about the distance between them had deepened. Their financial ability to sustain the Chicago dream was also more uncertain. Sidney shared his thoughts with Eva: “Hold on dear the best you can. If we don’t sacrifice now we’ll regret it the rest of our lives. . . . [Our sacrifice will enable us to] do [our] part of the world’s work. You don’t want me to fail to do my part do you? It is what a man sacrifices and accomplishes in life that develops him. Well dearie bye bye. I love you and those babies with all my heart.”[38] Not much later he penned, “I know you are lonely dear without me and heavens knows I am only too lonely myself. . . . So far as expenses are concerned dear it will be absolutely out of the question for us to be together in Chicago, much as I would like it. Living is awfully high here and rent is a fright. I’ll have to get you settled in a home and then make it by summers back here or during any quarter of 3 months that I can. Can you hold out till next June or September at the very latest depending on the money we can borrow? . . . Write and let me know dear. I know you will be lonely but if you can stick it out that far it sure would be a big help. . . . I w[as] figuring . . . last night . . . the cheapest way for me is to do just what I’m doing.”[39]

The demands of Sperry’s program remained unrelenting. He apologized to Eva: “I hope you will not think I am neglecting you too much. My course this quarter is so stiff that I am kept on the go. Hope to write you tomorrow. Bye Bye. Love Sid.”[40] This continued as he delved deeper into his studies: “Saturday I had to study Egyptian all day.”[41] Despite the grind, Sidney received good news just before Christmas that members of his old stake presidency in American Fork would sign on a loan note he took out to continue his studies and support his family. “Received the $500 check today and a letter from Pres. Chipman saying that he and his counselors would sign for me up to $1000. Awfully good of them. . . . I’m awful glad the money arrived when it did.”[42] Then on Christmas Eve he penned, “Dearest Eva: . . . Hope you got the money I sent you in time to get a little Christmas. . . . Wish it could have been all you needed or wanted. . . . Just got thru with exams. It’s an awful strain. . . . Heaps of love and kisses.”[43]

To conserve resources, Sidney never planned to travel to Utah for Christmas and would remain away from his family. His academically rigorous life continued in January unabated: “I’ll write often as possible. Am awfully busy.”[44] By the winter of 1926, the grind had taken its toll on both Eva and Sidney. For his part, he asked Eva a question: “Can you guess how much I weigh now? I weigh . . . 40 lbs less than when I last saw you. . . . Am looking forward . . . to September when I can be with you again. Life would be a dreary, dull existence without you and our kiddies.”[45] It had been almost nine months since he had seen Eva and Lyman, and he had never seen his oldest daughter. In his absence, his daughter had received her name and a blessing by another priesthood bearer. Sidney was happy about this since he would be gone too long for the family to wait. It would be another eight months before he would see them again or, in his daughter’s case, for the first time.

The winter quarter of 1926 would bring Sidney to his fourth course in Hebrew and another course in Egyptian, taught by the same professor in Egyptology who had encouraged him to consider it as a specialty. He would also study Greek and portions of the New Testament under a different professor of Biblical and Patristic Greek, Edgar Johnson Goodspeed. Finally, he studied what was then entitled “History of Antiquity II: The Oriental Empires, 1600 BC to Alexander the Great.” This course was typically taught by James Henry Breasted, though he was not in Chicago during this quarter,[46] and examined the civilizations of Egypt, Asia Minor, Assyria, Chaldea, the Hebrews, and Persia. The course also analyzed government, art, architecture, religion, and literature. Finally, it looked at the early civilization of Europe, both before and after the Indo-European migrations into Greece and Italy.

The spring quarter would further Sperry’s understanding of the history of early Christianity as he studied under his third distinct New Testament professor, Shirley Jackson Case. Sperry would also take another advanced course in Hebrew, study the history of Judaism, and learn Hieratic and Late Egyptian at the feet of James Henry Breasted, studying the main text of the course in German, and learning selected portions of Georg Möller’s Hieratische Lesestücke. By the end of spring, Sperry had formed a strong foundation of Egyptian, including demonstrating a proficiency in its hieroglyphic, hieratic, demotic, and Coptic scripts. The summer quarter was not only a culmination of his master’s work at Chicago before returning to Utah, but also a synthesis for Sperry as he strengthened his Semitic language prowess, learning from the preeminent American scholar who was also one of the most accomplished Assyriologists worldwide, D. D. Luckenbill.[47] Sperry also intensively studied the comparative grammar of the Semitic languages under Martin Sprengling, whose encyclopedic knowledge “followed the course of classical thought and its ramifications into the Judeo-Christian and Islamic worlds.”[48] Sprengling was a “severe but inspiring teacher,” and “his genius was at its best in the seminar room where his methods were often Socratic.”[49] Sperry followed in Sprengling’s footsteps in terms of the knowledge he amassed and in the fact that during the summer of 1926 he had already demonstrated high proficiency in Hebrew, Aramaic, Assyrian, and Syriac, though the mastery of this last language came later. Sprengling would later become one of Sperry’s major PhD dissertation advisers. For now, Sperry would complete his master’s thesis using his knowledge of Hebrew and the Book of Mormon.

In the summer of 1922, Elder Joseph Fielding Smith, Apostle and Church Historian, had written, “The study of Hebrew is the most important of all the languages for our young people at this time. . . . The day of the Gentile is drawing to its close and the day of the Jew is at hand, so far as the Gospel is concerned.”[50] The president of BYU concurred: “It seems to me very desirable for us to have scholars in various languages, particularly those which have had to do with the work of the chosen people of the Lord on the earth. Among these of course Hebrew ranks first. . . . I think it would be highly desirable for the Church University to offer courses in Hebrew . . . I should certainly like to have a good man in Hebrew connected with our institution if we could afford it.”[51] Elder Smith replied, “I have always regretted that we had no scholars in the Church who understand Hebrew and also Egyptian, both languages being of the greatest value to us.”[52]

Just over three and a half years later, Elder Smith must have been pleased to have received Sperry’s request for the First European edition of the Book of Mormon to assist in the writing of his thesis. For his thesis, Sperry planned to employ some of his now extensive Hebrew ability in producing and examining a collation of the parallel Masoretic, King James, and Book of Mormon Isaiah texts. Elder Smith was happy to loan Sperry a physical copy of the requested Book of Mormon.[53]

Under the direction of faculty members in Chicago’s Old Testament department, Sperry’s thesis was entitled “The Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon.”[54] Scholars of the Old Testament, of course, study variants in different versions of the same biblical text to answer questions about their provenance and history. Sperry’s thesis is one example of how he connected his study of the Book of Mormon to his Old Testament studies. As a rationale for his thesis topic, he explained,

The Book of Mormon makes plain that the Nephites brought the Brass Plates with them from Jerusalem. These were the Hebrew Scriptures giving an account from the creation down to the beginning of the reign of Zedekiah, King of Judah. In other words, the Nephites had with them a Hebrew bible containing the scriptures known in Israel prior to 600 BC. We might, therefore, expect to find quotations from the Brass Plates in the Book of Mormon. Not only so, but what is of greater interest to biblical scholars [is that] these quotations would presumably be from an uncorrupted text.[55]

Sperry began by providing a relatively “brief statement of the origin and contents of the Book of Mormon,” which, he stated, “will assist greatly in making clear the nature of the problem . . . of this thesis.”[56] He then stated, “Joseph Smith Jr. . . . affirmed he translated the Book of Mormon by the gift and power of God.” Before quoting from what would have been the forepart of the Book of Mormon then in circulation, Sperry referenced the First Vision as “a Divine manifestation of profound significance,” which Joseph had “received.”[57] He presented another rationale for the study: “There are to be found in the Book of Mormon numerous quotations from the Brass Plates including the sayings or writings of some prophets not mentioned in the Old Testament. An investigation of these quotations from the Brass Plates is important” because “there are about six hundred thousand people constituting the membership of . . . The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints . . . who believe the Book of Mormon to be a Divine record.”[58] Therefore, said Sperry, “such an investigation offers one avenue of scientific approach to the claims of the [Latter-day Saint] people.”[59]

Sperry then framed a question he wanted to answer: “Critics of the [Latter-day Saints] have often charged that the text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon has been taken bodily from the King James Version. Such charges, if true, would manifestly tend to disprove that the Book of Mormon is an independent record because it is a well known fact that the parallel text of Isaiah in the King James Version is very corrupt in many places.”[60] So Sperry’s question became whether or not all the text of Isaiah (about twenty-one complete chapters) in the Book of Mormon was simply the same as the King James Version of the Bible. If there were differences, that would provide evidence for the unique characteristics of the text in the Book of Mormon.

Some of his significant findings in regard to this main question include the following: 54 percent of the verses of the text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon “contain differences, compared with the King James’ version,”[61] and “many of these differences are very great.”[62] Thus the Book of Mormon text “points to very notable corruptions, where these differences occur, in our Masoretic texts.”[63] Furthermore, “the collation reveals so many great differences between the two texts that one is most compelled to doubt the veracity of such writers as Linn who infer The Book of Mormon text of Isaiah to have been ‘appropriated bodily’ from the King James’ text.”[64] Sperry then explains, “Where these great differences exist between The Book of Mormon and the King James’ version the modern critical Hebrew text favors in nearly every instance the reading as given by the King James’ translation.”[65] Again, this means that the Book of Mormon text is unique. Finally, “Critics have accused Joseph Smith of quoting verbatim from the King James’ version, not even omitting the italics supplied by the translators.”[66] It turns out, however, that “the Book of Mormon . . . has different translations at points where italics occur in” nearly half the verses.[67] Therefore, “considering the nature of the words in italics this is quite a striking evidence of Joseph Smith’s independence in translating the text of Isaiah.”[68]

Sperry’s thesis had thus demonstrated that the Isaiah text in the Book of Mormon was not “appropriated bodily” from the King James Bible but, rather, had its own unique fingerprint. His thesis could not have examined all the questions one might raise for inquiry regarding the text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon, but it yielded eight summary findings, all of which either added to our knowledge of the Book of Mormon, affirmed the Book of Mormon’s unique characteristics, or brought up fruitful questions for further investigation. Studying the words of Isaiah, as well as the Book of Mormon itself, became one of Sperry’s lifelong lines of inquiry that permeates most of his writings.

Not including his thesis, the final examination for his master’s degree (which would be accomplished by the end of the summer of 1926), or the previous twenty hours of graduate coursework Sperry had completed at BYU prior to Chicago, Sperry had now completed sixty-three hours of graduate coursework at Chicago in five terms, an arduous endeavor even for the most talented student. On August 26, 1926, Sperry passed his final examination for his master’s degree and on September 3, 1926, was awarded an AM degree in the Department of Old Testament Literature and Interpretation from the University of Chicago. He now had the foundation to pursue his PhD in ancient Near Eastern languages and civilizations.

At long last, he traveled home to reunite with his beloved Eva and their children, Lyman and Claire—the daughter he had never met. After reaching the train station in Salt Lake City, Sidney traveled further to Manti, Utah, where his family was staying. The reunion was joyful. Sperry would almost immediately take the position as principal of the Moroni Seminary in Sanpete County for the academic year 1926–27. In June 1927 Sperry would take the train back to Chicago once again to continue his quest to know more about the scriptures than any living person. This time, however, he stayed for only one quarter, to his family’s delight, during which he intensively studied and translated Isaiah texts, Babylonian texts, and other ancient texts.

He was asked to be principal at Pocatello Seminary in Idaho for the 1927–28 academic year, which would require the family to move from Manti, Utah, to Pocatello for one year. After that year, Sidney took his family back to Manti before returning to Chicago for another four quarters (summer, fall, winter, spring), from June 1928 to May 1929 to complete his PhD coursework. That Chicago summer continued to raise the level of Sperry’s ability in and knowledge of Hebrew, its Semitic relatives, and the manners and customs of the Hebrews as he studied under Ludwig Köhler, visiting professor of Old Testament from Zurich, Switzerland. During that time Sidney’s esteemed grandfather, patriarch Harrison Sperry Sr., passed away. He was believed to have been the last known Latter-day Saint to have personally known the Prophet Joseph Smith.[69] He was the very man who had spiritually predicted that Sperry would be doing what he was doing during this period. That fall Sidney continued growing in his mastery of textual analysis, translating, and interpreting, again focusing mostly on Hebrew and its Semitic relatives.

After the passing of Sperry’s grandfather the previous summer, the winter of 1929 provided new life. Sidney and Eva’s third child, and second son, Richard Dean Sperry, was born on January 5 in Manti. The winter also provided intensive opportunities for Sperry to further master Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, and other languages while at the same time to extend his knowledge and understanding of Arabic and Islamic studies. He also passed his language examinations in French and German in January and March, respectively. The spring quarter of 1929 found him deepening his knowledge of Arabic grammar, lexicography, rhetoric, and literature. During these last two quarters, Sperry worked closely with two of his dissertation advisors, William Creighton Graham and Martin Sprengling. On March 13, 1929, John Merlin Powis Smith recommended Sidney B. Sperry for a PhD from the Department of Oriental Languages and Literatures, and on April 13, 1929, the graduate faculty approved the recommendation. Since earning his master’s degree, Sperry had further taken fifty-one credit hours of intensive courses in many Semitic languages and demonstrated his mastery. The spring of 1929 was the last time Sperry would ever take courses again as a PhD candidate in Chicago. The Chicago journey had essentially come to a close.

Without interruptions, Sperry would likely have completed his PhD in 1929. In fact, in letters to Sperry from Apostles such as Elder Talmage, Church leaders were already addressing him as “Dr. Sperry.” While moving forward in early 1929 with his dissertation plans, two things happened that adjusted Sperry’s course. First, he received a call from Joseph F. Merrill, Church Commissioner of Education, requesting that he teach two Old Testament courses at BYU.[70] Each course would be six weeks in duration during the summer term and would be taught to seminary and institute teachers. Sperry accepted this opportunity with excitement and zeal, despite the fact that it would delay the completion of his PhD. By now Sperry was a “popular teacher in the seminary system,” and during his six-week course in the summer of 1929, he “ignited a fire in the seminary system with the new, critical approaches of . . . textual analysis, archaeological investigation, and historical exegesis” of the Old Testament.[71]

T. Edgar Lyon, a future renowned teacher and author, was extraordinarily impressed with Sperry’s knowledge and the way he opened up the scriptures. Never had Lyon seen the scriptures come alive quite like they did under Sperry’s tutelage. Inspired by his Chicago experience, his methodology, as well as his faith, was contagious. Sperry’s classes the summer of 1929 “were a revelation to Lyon and many other teachers in the [seminary] system.”[72] Lyon’s biographer writes of the impact of these summer sessions:

The summers of 1929 and 1930 [both of which Sperry organized himself] were life-changing educational moments for Lyon as well as his students. . . . From Sperry, Lyon realized that there was a new and exciting realm of biblical scholarship. He began to understand that education was not just listening to professors, reading their standard texts, and then reproducing canonized information on tests as he had done as an undergraduate. Rather, education and learning could be exciting, even thrilling, involving the use of original sources and ancient languages. Lyon learned that investigation of standard texts must be creative, using modern techniques and innovative approaches.[73]

Edward H. Holt, acting president of BYU in 1929, wrote to President Franklin Harris, who was in Russia, updating him on Sperry’s accomplishments in the Alpine summer school: “Sperry is pleasing the Seminary people very much. Dr. Merrill has been down four or five times and seems very much interested.”[74]

The second request was that Sperry direct the Latter-day Saint institute of religion adjacent to the University of Idaho in Moscow, Idaho. Sperry accommodated this request as well and was happy to do so because it benefited the Lord’s Church. He would serve as director of the institute at Moscow for two years after teaching at BYU in 1929. He would also assist Commissioner Merrill in securing world-class scholars to teach at BYU in the summers of 1930,[75] 1931, and 1932, while also organizing these courses.[76] But another event changed Sperry’s course once again.

Elder David O. McKay was a moving force in having Sidney B. Sperry and Guy C. Wilson become the two inaugural faculty members of a new, full-time religious education department at BYU.[77] Indeed, Elder McKay was extremely anxious for Sperry to simultaneously join Wilson at BYU full-time in the fall of 1930.[78] But Commissioner Merrill had the tough task of replacing Sperry in Moscow, Idaho, when there were no plausible replacements, which is why Merrill wrote to President Harris: “We think, however, that we can get [Elder] McKay to consent to postpone a year the coming of Brother Sperry.”[79] If Sperry would have come when Elder McKay intended, Sperry would have had the honor, with Wilson, of being one of the two inaugural full-time religious education faculty members at BYU. The fact that this scenario did not happen because the seminaries and institutes needed him for one more year is not a hindrance to Sperry’s contribution to BYU and the Church Educational System, but rather a testament to it. Furthermore, Sperry became the pioneer Elder McKay had hoped for once Sperry joined as the second full-time faculty member in the new department. During this period, Sidney and Eva received the gift of their fourth child and second daughter, Phyllis Sperry, born June 27, 1930, in Moscow, Idaho. Meanwhile he worked on completing his doctoral dissertation in preparation for his dissertation defense and final examination.

Sperry’s dissertation, entitled “The Scholia of Bar Hebraeus to the Books of Kings,” was a pioneering endeavor. Bar Hebraeus (1226–86), “one of the greatest historians of the Middle Ages,” was “particularly interested in reviving Syriac language and literature and in bringing Muslim scholarship to the attention of the Christians.”[80] Sperry wrote, “Bar Hebraeus made available for missionaries and laymen of the Syriac church, practically all the learning of his day. The amount of work he did was prodigious and covered the fields of grammar, history, lexicography, mathematics, astronomy, poetry, theology, philosophy and Biblical exegesis. Norman MacLean has written: ‘Perhaps no more illustrious compiler of knowledge ever lived.’”[81]

Sperry’s dissertation dealt with Bar Hebraeus’s commentary[82] on the biblical books of Kings. Specifically, it was an original translation into English—the first in history—of Bar Hebraeus’s commentary, which was originally composed in Syriac. Sperry collated eighteen different manuscripts, comparing the divergent texts so as to create the most faithful translation. Where the Syriac texts differed significantly, he noted and discussed those differences in his translation. Where they concurred, he noted those manuscripts that were in agreement. His dissertation comprised an introduction, translation, and collation of all Bar Hebraeus’s commentary material on the books of Kings, which amounted to about two hundred pages. Sperry’s dissertation was part of a larger work envisaged by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, in which all of Hebraeus’s notes on the Bible were to be “critically edited and translated” in order to issue a “critical edition of the Peshitto.”[83] The Peshitto was the first major translation from the putatively original Hebrew and Aramaic sources of the Old Testament into Syriac. To this day, the Peshitto version is the authoritative translation of the Bible in all of the Syriac-speaking churches,[84] including the “Syriac Orthodox, Assyrian church of the East, Maronite, Chaldean,” and Syrian Catholic.[85] Chicago scholars wanted to create the best translation possible of this Syriac translation of the Bible.

Furthering this objective, the Oriental Institute published Barhebraeus’ Scholia on the Old Testament: Part I: Genesis—II Samuel.[86] Martin Sprengling and William Creighton Graham edited this volume. The second volume would begin with what Sperry had created and would combine the work of others for the translations through Malachi, but this dream of making the second half of Hebraeus’s Old Testament commentary available in English was never realized. Sperry’s work was nonetheless well received, original, and informative. It not only highlighted the extreme care he took with his research but also marked his fluency in Syriac.

In the end, Sperry would return to Chicago for a number of weeks during the summer of 1931, culminating in his dissertation defense and examination. Upon passing, he received his PhD on August 28, 1931, from the Department of Oriental Languages and Literatures. Writing to Eva, Sidney exhaled, “The hard grind is finally over, I have reached my objective”; he wished she could have been with him at the graduation exercises.[87]

True to his never-ending quest to know as much of the scriptures as any earthly person could, he now desired to avail himself of a singular opportunity to go to the Holy Land. During this period, multiple General Authorities checked in on him, encouraging him to come to BYU. They were concerned he might go elsewhere, which he had frankly thought about. He was the prototype for what Church leaders had envisioned BYU could become. Because of his exemplary record of accomplishments at Chicago, he received a fellowship from the University of Chicago to do postdoctoral research in archaeology, languages, and history in the Near East for the 1931–32 academic year.

The first doctoral scriptural scholar of the Near East from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was now off to the Holy Land a century after the Church’s founding. Ross T. Christensen, a member of BYU’s religious education faculty, observed that Sperry “was actually the first serious student of the ancient Near East to appear among the Latter-day Saints since the days of the prophet Joseph Smith.”[88] After Sperry’s passing, Truman G. Madsen, himself a BYU faculty member of notoriety, perceived in 1978 that Sperry “was perhaps the Church’s most knowledgeable Hebraist.”[89] Madsen also indicated that Sperry “was a goldmine of knowledge and information that nobody tapped” and lamented: “I wish I could have tapped into all of his knowledge.”[90] Sidney B. Sperry had aspired to know the scriptures, the word of God, and to teach and learn God’s word the rest of his life. His scholarly influence and example of faithfulness to the restored gospel continues to inform Latter-day Saint religious scholarship today.

Notes

[1] Patriarch Harrison Sperry to Sidney B. Sperry, March 24, 1912, A Patriarchal Blessing, Salt Lake City, 1.

[2] Patriarch Sperry to Sidney Sperry, March 24, 1912, Patriarchal Blessing, 1.

[3] Truman G. Madsen, “Joseph Smith Lecture 2: Joseph’s Personality and Character” (Joseph Smith Lecture Series, Brigham Young University, August 22, 1978), www.speeches.byu.edu.

[4] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Chapter One: By Small and Simple Things: 1912–1935,” in By Study and Also by Faith: One Hundred Years of Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2015), 45.

[5] Roy A. Welker to George H. Brimhall, Paris, Idaho, August 22,1922, Franklin S. Harris Presidential Papers (hereafter Harris MSS), Brigham Young University Archives, Harold B. Lee Library, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Provo, Utah (hereafter Perry Special Collections).

[6] Samuel D. Moore Jr. and Sidney B. Sperry to Franklin S. Harris, Pleasant Grove, Utah, October 27, 1922, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[7] Moore and Sperry to Harris, October 27, 1922.

[8] Adam S. Bennion to Franklin S. Harris, November 3, 1924. Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections. “We are slighting [the Book of Mormon] in our present course.”

[9] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, July 11, 1925, in author’s possession. Sperry reflects that if he would have matriculated at Chicago in 1922 instead of enrolling at Brigham Young University, he would have completed his doctoral degree much sooner. Chicago’s summer term was “an ideal summer school.” He added, “It wouldn’t have cost me much more to have come here.” Concluding, he wrote, “We have to live and learn I guess.”

[10] The Relief Society Bible class of Weber Seminary to Sidney B. Sperry, Weber, Utah, March 6, 1925, in author’s possession.

[11] See, for example, Harris MSS, Boxes 1–22, Perry Special Collections.

[12] Franklin S. Harris to C. B. Lipman, Provo, Utah, September 8, 1923, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[13] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, July 11, 1925.

[14] Thomas W. Goodspeed, A History of the University of Chicago: The First Quarter-Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1916), 472.

[15] Thomas W. Goodspeed, The Story of The University of Chicago, 1890–1925 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1925), 228.

[16] William M. Murphy and D. J. R. Bruckner, eds., The Idea of the University of Chicago: Selections from the Papers of the First Eight Chief Executives of the University of Chicago from 1891 to 1975 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 366.

[17] James Henry Breasted, Oriental Forerunners of Byzantine Painting: First Century Wall Paintings from the Fortress of Dura on the Middle Euphrates (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, 1924), 15.

[18] Nabia Abbott, “Martin Sprengling, 1877–1959,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 19, no. 1 (January 1960): 54–55.

[19] M. W. Poulson to Franklin S. Harris, Chicago, May 26, 1925, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections. The article is attached to this letter.

[20] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, July 31, 1925, in author’s possession.

[21] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, July 26, 1925, in author’s possession.

[22] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, July 26, 1925.

[23] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, July 31, 1925; emphasis added.

[24] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, July 31, 1925.

[25] J. M. Powis Smith Papers, Biographical Note, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library. The referenced journal later became the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, https://

[26] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, August 2, 1925, in author’s possession.

[27] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, August 13, 1925, in author’s possession.

[28] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, August 13, 1925; emphasis added.

[29] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, October 1925, in author’s possession.

[30] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, August 21, 1925, in author’s possession. Lunn’s theme that evening may have come from Arthur C. Lunn, “Some Aspects of the Theory of Relativity,” Physical Review 19, no. 3 (1922): 264–65. The “group of men” referred to by Sperry may have been part of what was called the Innominates club, of which Lunn was an organizing member. It included a cadre of faculty intellectuals from the departments or fields of anatomy, bacteriology, chemistry, botany, geology, mathematics, physics, physiology, zoology, and psychology.

[31] George B. Kauffman, “Martin D. Kamen: An Interview with a Nuclear and Biochemical Pioneer,” Chemical Educator 5 (October 2000): 252–62, https://

[32] Kauffman, “Martin D. Kamen,” 252–62. In 1929 Lunn, together with his colleague in chemistry, published his seminal work. See Arthur C. Lunn and James K. Senior, “Isomerism and Configuration,” Journal of Physical Chemistry 33 (1929): 1027–79.

[33] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, September 3, 1925, in author’s possession.

[34] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, October 1925.

[35] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, October 1925.

[36] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Hammond, Indiana, September 21, 1925, in author’s possession.

[37] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, September 21, 1925.

[38] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Hammond, Indiana, September 18, 1925, in author’s possession.

[39] S. B. Sperry to E. B. Sperry, September 21, 1925.

[40] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, October 21, 1925, Chicago, in author’s possession.

[41] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, November 1, 1925, Chicago, spelling corrected, in author’s possession.

[42] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, December 15, 1925, Chicago, in author’s possession.

[43] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, December 24, 1925, Chicago, in author’s possession.

[44] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, January 15, 1926, Chicago, in author’s possession.

[45] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, February 6, 1926, Chicago, in author’s possession.

[46] Charles Breasted, Pioneer to the Past: The Story of James Henry Breasted, Archaeologist (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1943), 388–94.

[47] Leroy Waterman, “Daniel David Luckenbill, 1881–1927: An Appreciation,” American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 44, no. 1 (October 1927): 1–5.

[48] Abbott, “Martin Sprengling, 1877–1959,” 54–55.

[49] Abbott, “Martin Sprengling, 1877–1959,” 54–55.

[50] Joseph Fielding Smith to Franklin S. Harris, Salt Lake City, September 5, 1922, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections. He indicates that Elder John A. Widtsoe of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and President Anthony W. Ivins of the First Presidency concur that Hebrew is preeminent and should be taught.

[51] Franklin S. Harris to Joseph Fielding Smith, Provo, Utah, September 7, 1922, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[52] Joseph Fielding Smith to Franklin S. Harris, Salt Lake City, September 11, 1922, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections. “We stand in a peculiar position as a people, in regard to education, because of the message we have for the world. The Gospel was to be preached first to the Gentile and then to the Jew (D&C 90:9). The time has now come when the Gospel message must go to the Jew and to the Lamanite, in fulfillment of the predictions of old. The Jew is, as the Book of Mormon declares he would do, ‘beginning to believe in Christ.’ We are certainly in need of missionaries who are acquainted with Hebrew and Jewish customs so that they will understand how to appeal to these scattered sheep of the House of Israel.”

[53] Joseph Fielding Smith to Sidney B. Sperry, Salt Lake City, May 24, 1926, in author’s possession.

[54] Sidney B. Sperry, “The Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon” (master’s thesis, University of Chicago, 1926), title page. Submitted to the faculty of the graduate school of arts and literature for his master of arts degree.

[55] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 8–9.

[56] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 1.

[57] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 1.

[58] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 9. Sperry makes a point to write: “The correct name is, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

[59] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 9.

[60] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 10.

[61] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 79.

[62] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 82.

[63] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 83.

[64] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 79.

[65] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 79.

[66] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 80.

[67] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 80.

[68] Sperry, “Text of Isaiah in the Book of Mormon,” 80.

[69] Associated Press, July 29, 1928. “Harrison Sperry, 96, the oldest member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints died at his home here yesterday. The church patriarch was believed to have been the only person living who personally remembered Joseph Smith, founder of the church.”

[70] Franklin S. Harris to Joseph F. Merrill, January 26, 1929, Provo, Utah, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[71] Thomas Edgar Lyon Jr., T. Edgar Lyon: A Teacher in Zion (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002), 115.

[72] Lyon Jr., T. Edgar Lyon, 115.

[73] Lyon Jr., T. Edgar Lyon, 118.

[74] Edward H. Holt to Franklin S. Harris, July 7, 1929, Provo, Utah, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[75] Joseph F. Merrill to C. Y. Cannon, Sidney B. Sperry, E. H. Holt, September 26, 1929, Provo, Utah, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections. “In order to . . . keep our seminary men well satisfied . . . I think it well to get some scholar of national standing next summer to offer two courses in the field of the New Testament. . . . I certainly hope that . . . arrangements can be made with Dr. Goodspeed.” None of these men copied on the letter intimately knew Goodspeed except for Sperry. This letter is, in effect, to him in order to make the invitation and connection. Cannon is involved because he was the dean of the Alpine summer school at the time and Holt is involved because he is the secretary to the faculty and serving as acting president while Harris was in Russia. These brethren were to make the logistics work and conduct official arrangements.

[76] Lyon Jr., T. Edgar Lyon, 115.

[77] Joseph F. Merrill to Franklin S. Harris, March 28, 1930, Provo, Utah, Harris MSS, Perry Special Collections.

[78] Merrill to Harris, March 28, 1930.

[79] Merrill to Harris, March 28, 1930.

[80] Joseph R. Strayer, ed., Dictionary of the Middle Ages (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1983), 2:108.

[81] Sidney B. Sperry, “The Scholia of Bar Hebraeus to the Books of Kings” (PhD diss., The University of Chicago, 1931), 4.

[82] Scholia is a commentary on a particular subject, usually in the Latin or Greek classics.

[83] Sperry, “Scholia of Bar Hebraeus,” 4.

[84] See, for example, M. P. Weitzman, The Syriac Version of the Old Testament: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 2. “The [Peshitta] assumes . . . importance as the basis of the rich literature of Syriac-speaking Christianity.” See too http://

[85] See http://

[86] See Martin Sprengling and William Creighton Graham, eds., Barhebraeus’ Scholia on the Old Testament: Part I: Genesis—II Samuel, ed., James Henry Breasted and Thomas George Allen (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1931).

[87] Sidney B. Sperry to Eva B. Sperry, Chicago, August 18, 1931, in author’s possession.

[88] Ross T. Christensen, “Sidney B. Sperry,” Newsletter and Proceedings of the SEHA 143 (May 1979): 6.

[89] Madsen, “Joseph’s Personality and Character.”

[90] Truman G. Madsen, conversation with author, October 30, 2005.