The Experience of Israelite Refugees

Lessons Gleaned from the Archaeology of Eighth-Century-BC Judah

George A. Pierce

George A. Pierce, “The Experience of Israelite Refugees: Lessons Gleaned from the Archaeology of Eighth-Century-CC Judah,” in Covenant of Compassion: Caring for the Marginalized and Disadvantaged in the Old Testament, ed. Avram R. Shannon, Gaye Strathearn, George A Pierce, and Joshua M. Sears (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book), 323‒52.

George A. Pierce is an assistant professor of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University.

Statistics from the United Nations Refugee Agency show that at the end of 2019, “79.5 million individuals have been forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations.”[1] Thus, while public attention often shifts to other concerns such as pandemics, politics, or economics, the refugee situation is persistent, requiring attention. Refugees have a prominent, although sometimes overlooked, place in biblical and Restoration scripture and in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from its nascent years in Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois to the present. Notably, this includes Elder Dieter F. Uchtdorf, who was a refugee early in life and has shared lessons learned from that experience.[2] Church authorities have alerted and instructed members about the plight of modern refugees and encouraged activities that would provide aid and comfort to such displaced persons.[3] Further, the Church has provided supplies to refugees in fifty-six countries, volunteered time and efforts to help integrate displaced persons into new communities, and dedicated a website to increase refugee awareness and to suggest ways members can be of assistance.[4]

The ancient kingdom of Judah faced similar migrations of displaced persons from the northern kingdom of Israel. While the eighth century BC started as a period of great prosperity for both kingdoms, that century witnessed the conquest, exile, and devastation of the kingdom of Israel and an Assyrian campaign that greatly affected Judah. Starting with the Syro-Ephraimite War (2 Kings 16:5–7; Isaiah 7), the Assyrian empire, ruled by Tiglath-pileser III, conquered and annexed the Galilee in 732 BC.[5] Later, the Assyrian king Sargon II laid siege to Samaria, fully conquering the northern kingdom in 721 BC (2 Kings 17:6–23). While some of Israel’s population was left in the land, nearly forty-one thousand citizens of the northern kingdom of Israel were deported and sent into exile.[6] Thousands more escaped the ruin and desolation of the Assyrian onslaught by migrating south to Judah as displaced refugees.

Figure 1. Map of Israel and Judah in the eighth century BC. Map by the author.

Figure 1. Map of Israel and Judah in the eighth century BC. Map by the author.

This paper examines the textual and archaeological evidence for Israelite refugees in the kingdom of Judah in the eighth century BC and what we, as modern believers, can learn from the material culture, experience, and treatment of refugees in Judah. This paper attempts to show the relevant practical applications that may arise from supplementing scripture with archaeology and what lessons for interacting with and assisting the disenfranchised and marginalized within society may be gleaned from both the archaeological and biblical records. Lessons from the prophetic oracles about Judah and its relationship with both the Lord and the displaced persons from the northern kingdom, while initially intended for the ancient Judahites, continue to have relevance and practical application for modern believers.

Refugees in the Biblical Text

In the Old Testament, the status and experience of characters as settled or migrant/

Despite the recurring motif of refugees elsewhere across biblical genres, the Old Testament historical narratives of 2 Kings and 2 Chronicles are curiously silent about the migration of refugees from the kingdom of Israel to the kingdom of Judah as a result of Assyrian campaigns. Because of this gap in biblical history, the presence and experience of these expatriates and lessons for the modern believer can best be gleaned from the archaeological record. The experience of the Judahites and the prophetic critique to trust in the Lord also provide an additional lesson for the modern believer.

Refugees and the Archaeology of Judah and Jerusalem

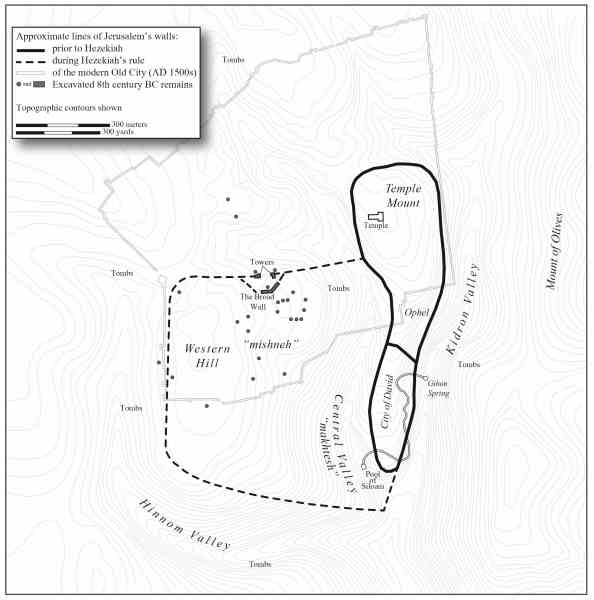

Figure 2. Map of Jerusalem in the eighth century BC. Map by the author.

Figure 2. Map of Jerusalem in the eighth century BC. Map by the author.

Ancient Jerusalem was situated on two hills framed and divided by three main valleys. The Eastern Hill comprises the spur called the City of David, the Temple Mount, and a saddle between the two known as Ophel. The Kidron Valley to the east and the Tyropoeon (or Central) Valley to the west define the Eastern Hill. The Western Hill is topographically higher than the Eastern Hill and is demarcated by the Tyropoeon Valley to its east and the Hinnom Valley to the west and south. In the later biblical periods, the Western Hill was known as the mishneh (“the second district”; 2 Chronicles 34:22 Christian Standard Bible) and the Tyropoeon Valley was likely the maḵtēš (“hollow” in Christian Standard Bible) mentioned in Zephaniah 1:11. The Gihon Spring, near the base of the City of David’s eastern slope, was the primary source of water throughout the Old Testament period.

Because of Jerusalem’s role as the royal city of the Davidic monarchy and its centrality for worship, biblical scholars and archaeologists in the Holy Land have sought to determine the location and extent of Jerusalem’s boundaries during the biblical period prior to the Babylonian conquest. Archaeological excavations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries indicate that the earliest traces of settlement were on the Eastern Hill, specifically the spur called the City of David. The date of settlement of the Western Hill and the extent of Jerusalem have also been debated. Did biblical Jerusalem encompass both hills, or was it limited to the City of David and the Temple Mount until the Second Temple period?

Archaeological fieldwork conducted in Jerusalem by Israelis after the Six-Day War provides some answers to these questions. Throughout much of its history, Jerusalem has occupied two hills: the Eastern Hill (City of David, Ophel, and the Temple Mount) and the Western Hill. However, only the Eastern Hill was occupied from Jerusalem’s beginnings in the Neolithic period until sometime in the eighth century BC. Tombs on the western side of the Eastern Hill that date to the ninth century BC provide a boundary for expansion of the city at least until sometime after that date.[7] The Western Hill has shown few signs of any activity until at least the late ninth–early eighth centuries BC in the form of small, scattered agricultural installations with little to no architecture related to habitation. Excavations in the present-day Jewish Quarter of the Old City, located on the Western Hill, revealed increased, extensive construction efforts dated to the last quarter of the eighth century BC.[8] The excavators dated four phases of construction using pottery associated with the floors and walls. The structures were made of undressed field stones with plastered walls. Floors that survived consisted of crushed and tamped chalk or beaten earth. The ceramic assemblage dated from the mid-eighth century through the early seventh century BC based on parallels to other Judahite sites such as Lachish, Beersheba, Arad, and Beth Shemesh. Other excavation areas in the Jewish Quarter exposed mostly fragmentary walls and floors with some indication of an agricultural installation for pressing olives or grapes. Additional building remains were found in excavations at the Jerusalem Citadel near Jaffa Gate, the Armenian Garden, and on Mount Zion. Because of the position of houses beyond fortified areas, excavators were confident that this portion of Jerusalem was unwalled and outside the defensive walls of Jerusalem.[9]

Figure 3: Eighth-century-BC architecture excavated in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. Photograph by Zev Radovan.

Figure 3: Eighth-century-BC architecture excavated in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem. Photograph by Zev Radovan.

Finds in this area included ceramic figurines depicting women that may be connected to fertility (termed Judahite Pillar Figurines), animal figurines, and storage jars bearing royal seal impressions.[10] Two seals, used to sign documents and verify identity, were found. One bears the name “Sapan (son of) Abima‘as,” and the other reads “Menahem (son of) Yobanah.” An ink inscription on a storage jar fragment (an ostracon) contained the name Mikhayahu and the phrase [’Ēl] qōnēh ’ārēṣ, meaning “God creator of earth.”[11] Writing discovered on an additional ostracon possibly refers to an examination or investigation about taxes and an individual named Bqy (biblical Bukki), a name connected to the tribe of Dan (Numbers 34:22).[12] These finds, though not overwhelming in their character, may indicate an affiliation of these individuals with the northern kingdom of Israel, as discussed below.

The seemingly sudden flourish of building activity on the Western Hill during the eighth century BC observed in the archaeological record precipitated questions about the demography of Jerusalem in the centuries prior to the Babylonian destruction and what may have caused such growth. Archaeologists estimate that the population of Jerusalem prior to the eighth century BC was around six to eight thousand people and then swelled to approximately twenty to thirty thousand people in the second half of the eighth century.[13] This rapid development cannot be explained by natural population growth or economic expansion.[14] Magen Broshi suggests “two waves of mass migration” of refugees: the first from the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel from 732 to 721 BC and the second from Sennacherib’s campaign against Judah and Philistia in 701 BC. This theory, with some modification and nuance, has been generally accepted.[15] Assessing the archaeological, anthropological, and historical evidence, the presence of refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel settling in Judah and Jerusalem is difficult to dispute.

The city of Jerusalem was not the sole city to experience a population increase during the late eighth century BC. Other Judahite cities—including Beersheba, Tell Beit Mirsim, and Lachish—also experienced growth. The number of settlements in the hills south of Jerusalem and in the region of lower hills to the west of Judah bordering the coastal plain called the Shephelah similarly increased. Archaeological surveys have documented eighty sites in the hill country south of Jerusalem and only twenty-one in the Judean Shephelah dated to the tenth and ninth centuries BC. In the mid to late eighth century BC, the number of settlements increased to 100 in the southern hill country and 250 in the Shephelah.[16] Archaeologist Israel Finkelstein suggests that the sites in the Shephelah were established after 734 BC when Judah became a vassal to Assyria and integrated into the Assyrian economy, and these sites were olive oil production centers attracting “Israelite experts in olive culture and olive oil industry.”[17] Throughout the kingdom of Judah, as much as half of the population may have consisted of displaced refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel.[18]

The death of Sargon II in 705 BC afforded an opportunity for the Judahite king Hezekiah to rebel against his vassal status to Assyria. As part of his rebellion, and in preparation for an expected Assyrian retaliation by the new king, Sennacherib, Hezekiah implemented administrative and public works projects reflected in the archaeology of biblical Jerusalem. Commodities such as wine, oil, and grain were gathered from farms and royal estates and collected in storage jars with stamped handles bearing royal seal impressions. These jars and their contents were redistributed to fortified centers, likely to serve as food reserves for those centers in case of Assyrian siege.[19] Areas of Jerusalem that developed in the eighth century BC as a result of refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel, such as the Western Hill with its residential buildings, agricultural installations, and other extramural architecture, represented a sizable area of the city. The residents of this newly developed area of Jerusalem, likely displaced persons and families from the northern kingdom of Israel, were left vulnerable because of their location outside the established city walls, and this exposed population necessitated the construction of a fortification wall to protect this part of Jerusalem.

While excavating the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem, Nahman Avigad and his team uncovered a massive fortification wall dated to the late eighth century BC and the period of King Hezekiah (2 Chronicles 32:5).[20] Archaeological excavations of this so-called “Broad Wall” revealed a 65-meter (213 feet) stretch of wall 7 meters (23 feet) wide that was preserved up to 3.3 meters (11 feet) high in places. This served as the foundation for a much taller superstructure of stone or mud bricks that did not survive.[21] In places, the wall was constructed on bedrock, but Avigad’s team found that some building foundations were intentionally filled to provide a foundation for this massive fortification wall. Because of building activities of later periods, the course of the wall cannot be accurately determined, but Avigad posited that the wall was part of a fortification system that encompassed nearly all of the Western Hill and joined with the fortification around the City of David and the Temple Mount.[22]

Figure 4. A portion of the “Broad Wall” built in the eighth century BC. Note the houses in the upper portion of the picture over which the wall is built. Photograph by Zev Radovan.

Figure 4. A portion of the “Broad Wall” built in the eighth century BC. Note the houses in the upper portion of the picture over which the wall is built. Photograph by Zev Radovan.

Another element of Hezekiah’s preparation for revolt against the Assyrians was the digging of the Siloam Tunnel (2 Kings 20:20; 2 Chronicles 32:3–4). This project stemmed from the need to provide water to the growing population of the Western Hill as well as the necessity of protecting Jerusalem’s water supply from Assyrian forces should Jerusalem be besieged. This engineering feat diverted the waters of the Gihon Spring from the eastern side of the City of David underground to a pool in the Tyropoeon Valley between the Eastern and Western hills within the city walls. The tunnel runs for 643 meters (2,100 feet) and was accomplished by two teams cutting through the bedrock from opposite ends, following natural fissures in the limestone.[23] Given the tools and geology, it is estimated that the tunneling took at least four years to complete. After the tunnel was completed, an account was inscribed on the walls of the tunnel:

[The day of] the breach. This is the record of how the tunnel was breached. While [the excavators were wielding] their pick-axes, each man toward his co-worker, and while there were yet three cubits for the brea[ch,] a voice [was hear]d each man calling to his co-worker; because there was a cavity in the rock from the south to [the north]. So on the day of the breach, the excavators struck, each man to meet his co-worker, pick-axe against pick-[a]xe. Then the water flowed from the spring to the pool, a distance of one thousand and two hundred cubits. One hundred cubits was the height of the rock above the heads of the excavat[ors].[24]

Both the Broad Wall and the Siloam Tunnel required a massive effort from large crews of laborers who constructed the fortifications and hewed out the watercourse, and we can infer the identities of those who carried out such projects, as discussed below.

Arguments against Refugees

While the validity of the hypothesis that Jerusalem’s growth was the result of northern refugees has been widely recognized since the 1970s, some scholars have recently questioned the influx of refugees into Jerusalem and Judah and their influence on population and society, arguing against any Israelite presence in the southern kingdom after the fall of Samaria.[25] Certain archaeologists suggest that the areas of the Western Hill in Jerusalem experienced a gradual development during the eighth century BC rather than a raid growth accompanying a flood of refugees.[26] Biblical scholar Nadav Na’aman makes four claims against an influx of refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel into Judah and Jerusalem. First, he states that an “unbroken settlement in Jerusalem for hundreds of years makes it impossible to test the theory of enormous population growth in the city as a result of mass migration from Israel after its annexation by the Assyrians in 720 BCE.”[27] Second, Na’aman asserts that the Assyrians would not permit a large population of refugees to move from Israel to Judah. He claims that Hezekiah would not have interacted with the inhabitants of Samaria, painting a picture of Assyrian troops guarding the borders and sweeping the countryside for captives and people to exile.[28] Third, Na’aman argues that the absence of Israelite names with the theophoric element -yau, a shortened form of Yahweh (the Hebrew version of the name Jehovah), in surviving inscriptions, seals, or sealings indicates the absence of northern Israelite refugees in Jerusalem in the last quarter of the eighth century BC.[29] Finally, Na’aman bolsters his argument against the rapid growth of Judah and Jerusalem by noting the apparent dearth of artifacts that are distinctly Israelite, rather than Judahite, that would signal the presence of refugees.[30] He does concede that if there were “immigrants from Israel [who] arrived in Judah after Sargon’s campaign, they were not very numerous, [and] that many of them soon returned to their ancestral lands”; however, he does not draw upon any biblical or extrabiblical texts or any archaeological evidence to substantiate his claim.[31]

Textual and Archaeological Indications of Refugees

While some of these critiques warrant attention and nuance regarding the archaeology of biblical Jerusalem, Finkelstein and others have published more recent rebuttals and reappraisals based on more current archaeological evidence, anthropological observations, and textual studies of the Bible and Assyrian sources. Excavations have shown that some areas of the Western Hill and its slopes were already gradually being developed in the ninth–eighth centuries BC.[32] However, these are not the same areas excavated by Avigad. While one area may have had some evidence of settlement, most of the Western Hill buildings are later than the mid-eighth century BC based on parallel ceramic assemblages dated by radiocarbon to 766–745 BC at Beth Shemesh, a Judahite site in the Shephelah.[33]

Concerning the pace of the refugee arrival and construction of buildings on the Western Hill, it is helpful to recognize two anthropologically observed types of refugee movement. Anticipatory movement ahead of a crisis is typically accomplished by those whose social standing allows them the option to flee. In contrast, acute movement occurs in a crisis when individuals have little time to prepare to leave; this movement is usually a last resort by those who are less wealthy.[34] Acknowledging the potential for refugees from the Galilee to migrate to southern Samaria as early as 732 BC, and other refugees from Samaria to Judah up to and after 720 BC, we must realize that the influx of refugees was a process that lasted for more than a decade and that there was likely a second wave with the 701 BC campaign of the Assyrian king Sennacherib in Judah. This runs counter to Na’aman’s biggest assumption—that refugees moved from Israel to Judah after the conquest of Samaria by Sargon II and the annexation of the northern kingdom into the Assyrian empire.[35]

Scholarly claims about Hezekiah’s reluctance to upset Assyria, assertions of Assyria’s strict policies for refugees, and examples of refugee extradition have little relevance bearing on the plight of Israelite refugees moving to Jerusalem and Judah in the eighth century.[36] Attestations of vassal treaties detailing the responsibilities of a vassal king within the Assyrian empire have been translated and studied for their details. Often called loyalty oaths or loyalty treaties by scholars (Akkadian adê sakānu), these documents formally bound a subject to the Assyrian empire through a series of oaths, along with curses if the oaths were not upheld. Assyrian kings imposed these loyalty oaths on kings, provincial governors, and peoples throughout the empire—“the people of Assyria, great and small.”[37] Examples of Assyrian loyalty or vassal treaties for the land of Israel mention payment of tribute by the Israelite kings Jehu, Joash, and Menahem, as well as oaths for the Philistine cities of Ashkelon and Ekron in the Assyrian annals of Tiglath-pileser III and Sennacherib.[38] No example of treaties is currently known for the kingdom of Judah, although Ahaz the Judahite king is mentioned as a vassal paying tribute to the Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III (2 Kings 16:7–8; 2 Chronicles 28:16–21).[39] Interaction between the kingdoms of Israel and Judah in the eighth century BC, including diplomatic contact and reports from northern refugees, would have informed Judahites, including the prophet Isaiah, about the Assyrian vassal policies and the royal ideology against which King Hezekiah and Isaiah would contend in their own ways.[40]

Regarding the lack of Israelite theophoric elements in names, the meager number of personal names attested in eighth century BC Judah prevents any strong case being made either way. Na’aman states that the “assumption that Israelite refugees joined the leadership of the kingdom of Judah in a matter of a few years, and that Hezekiah chose to integrate them into his senior administration, above the main clans of Judah, seems most unlikely.”[41] However, recent excavations have recovered a sealing (the impression of a stamp seal) bearing the name “Ahiav ben Menahem” that may indicate the presence of Israelite refugees in the City of David.[42] Both of these names are attested in the Bible as names of northern kings. “Ahiav” is a textual variant of the name Ahab, attested only as an infamous king of Israel in 1 Kings 16:29–22:40 and as a false prophet at the time of Jeremiah in the seventh century BC. Menahem appears in the Bible only as the name of a king of the northern kingdom.[43] Avigad also found the name Menahemon on a seal impression in the Jewish Quarter excavations and also recovered an ostracon with the name Bqy that may be connected to the tribe of Dan. Additionally, Shebna, an official of King Hezekiah who received chastisement in Isaiah 22:15–19, may have a shortened name that was northern Israelite in origin.[44]

If these individuals were from the kingdom of Israel, it is likely that Hezekiah sought to integrate these northerners into the kingdom of Judah to unify the people. The prophecy of Isaiah 9:1–7 may have been seen as “commentary and political policy.”[45] Individuals and families hailing from elite backgrounds would probably have fled Israel in an anticipatory movement years ahead of the actual Assyrian siege. As biblical scholar William M. Schniedewind posits, the refugees from the north were likely not farmers or pastoralists or unskilled labor.[46] Rather, it is more likely that the northern Israelites who initially fled to Judah in anticipation of Israel’s destruction were skilled craftsmen or social and cultural elites such as priests, scribes, or government officials, many of whom would have been literate.[47] The critique of Micah 3:9–10 against the “heads of the house of Jacob, and princes of the house of Israel” who were perverting justice may allude to the integration of northern Israelite elites integrated into the administration of Judah.[48] Archaeologist Aaron A. Burke suggests that the Israelites from the northern kingdom who migrated to Judah were “merchants and emissaries who were abroad at the time of the invasion, but also more substantial groups of individuals living near borders.”[49] The ancestors of Lehi may likely have emigrated from their tribal territory of Manasseh in Israel to Jerusalem at this time.

Although names may not provide strong evidence of an Israelite presence, unnamed or unattributed compositions such as the Siloam Tunnel inscription suggest an Israelite element to the workforce that dug the tunnel. A reading of the Siloam Tunnel inscription indicates that it was not a royal dedicatory inscription to commemorate the completion of the waterway under Hezekiah’s auspices. The text does not mention the king or a deity, and it was located six meters (twenty feet) inside the tunnel from its outlet at the Pool of Siloam. Gary A. Rendsburg and Schniedewind suggest that the inscription is the product of “engineers, craftsmen, and labourers whose aim was to commemorate their accomplishment.”[50] Within the inscription, some elements (the form re‘ô for “friend,” the use of hāyāt rather than hāyâ for “there is,” mōṣ’ā for “spring,” and nqbh rather than ate‘ālâ for “tunnel or conduit”) appear to be connected to an Israelian dialect of Hebrew prevalent in Ephraim and Benjamin, rather than to Jerusalemite Hebrew. These elements led Rendsburg and Schniedewind to suggest that the author of the inscription and those responsible for the construction of Hezekiah’s Tunnel were Israelite refugees from southern Samaria, “somewhere along the Ephraim-Benjamin border.”[51] While Rendsberg and Schniedewind’s proposal has been met with some skepticism, their efforts to show that the labor force likely included northern Israelite refugees acknowledge the reality of integrating displaced persons into society as part of a royally commissioned project.

Regarding distinctly Israelite artifacts in Judahite contexts, no clear distinction can be made between common pottery of Israel and Judah in the eighth century BC, given the similarities in vessel type, form, and decoration. This lack of distinguishing features is not surprising given the close contacts between the kingdoms, which shared a cultural heritage, a language, and social customs. Differences in tomb construction and layout between the tombs in the Kidron Valley and present-day Silwan near the City of David and tombs in the Hinnom Valley west of Jerusalem and to the north of Jerusalem at the Basilica of St. Etienne may indicate the presence of northern Israelites, but the dearth of Iron Age burials from Samaria hinders any detailed comparison.[52] Finklestein lists several Israelite influences and cultural elements present in the material culture and architecture of Judah in the late eighth century BC.[53] These include olive oil production facilities in Judah showing technology from the northern kingdom; northern elements of pottery forms present in the ceramic assemblage at late eighth-century Beersheba; limestone cosmetic bowls and square bone seals that abound in Israel and later appear in Judah; ashlar masonry (stones that are dressed into rectangles) that appears at northern sites such as Megiddo and Samaria and appear later in the eighth century at Beersheba and Ramat Rahel; longitudinal pillared buildings likely used as storehouses or stables at Megiddo in the late ninth and early eighth century that are later seen in the eighth and early seventh century BC at Beersheba; voluted palmette capitals found at Megiddo, Hazor, and Samaria that appear in later architecture at Ramat Rahel, the City of David, and other locations peripheral to biblical Jerusalem;[54] and, according to Finkelstein, the incorporation of northern texts and traditions into the Judahite literature that would become the Bible.

Lessons from Biblical Archaeology and the Plight of Refugees

Although some scholars have debated “the validity of the notion of refugees” in ancient Israel and Judah,[55] the evidence of a rapid settlement in Jerusalem, an increase of settlements in the hill country and Shephelah, names with Israelite affiliation on seal impressions, Israelite Hebrew in the Siloam Channel, and numerous cultural elements and influences indicate that Israelite refugees were present in late-eighth-century-BC Judah. Using a framework designed to identify risks faced by refugees being resettled in a new area, Burke relates the perils encountered by modern refugees to those of the ancient world, highlighting efforts employed to mitigate those risks. Such jeopardies include landlessness, joblessness, homelessness, marginalization, food insecurity, increased morbidity and mortality, loss of access to common property assets, and community disarticulation.[56] Burke demonstrates that each of these risks were lessened by the efforts of the Judahite administration led by Hezekiah. He suggests that the Israelite refugees either (1) became dependent on the king to provide until they were integrated into the local economy by finding labor wherever possible, or (2) were employed on royal work projects, accomplishing needful objectives for the state.[57]

Burke states that “the construction of the Siloam Tunnel, as well as the dismantling of houses, quarrying of stone, and the construction of the Broad Wall, as well as the work required for water systems attributed to Hezekiah were, therefore, much more than strategic planning by Judah for a future Assyrian attack. They must also be regarded as elements of a shrewd approach to the gainful employment of Jerusalem’s landless and unemployed Israelite refugee population in an effort to secure their allegiance.”[58] This would have been crucial because scholars estimate that 53 percent of the population of Jerusalem and nearly half of the overall population of Judah consisted of Israelite refugees.[59] By using Israelite labor to accomplish these projects, Hezekiah and the administration provide a lesson in mitigating marginalization of refugees by providing an avenue of integration and unity with their new community.

Schniedewind and Finkelstein both suggest that Judah benefited from the influx of cultural elite Israelite refugees. These elites brought an increased literacy that helped to bolster the literacy of Judah and also influenced the development of the Hebrew Bible. The northern Israelite refugees that were integrated into the Judahite government probably helped the Judahite state to become more organized. As Finkelstein states, “A fully organized and well-administered state in Judah is the outcome of the [refugee] processes that took place in the late 8th century B.C.”[60] Including refugees and their descendants into local administration at any level, not only for representation of these peoples but also to use their learned skills, is an important lesson for any group trying to integrate a refugee population.

It is worth noting that instructions on the treatment of “strangers” (Hebrew gēr), those vulnerable persons who are outsiders in relation to a core family, are found in various biblical law codes, including the Covenant Code (Exodus 22:20–23:9, 12), the Holiness Code (Leviticus 17–26), and throughout Deuteronomy.[61] While answers to the risks of landlessness, homelessness, joblessness, and morbidity may be seen in archaeological correlates, the biblical gēr laws focused on inclusion of displaced and vulnerable people to mitigate food insecurity and loss of access to common property while providing food and access to community resources such as gleaning (Deuteronomy 14:21, 24:19–22).[62] Lessons about inclusion are apparent from the participation of gēr in feasts, festivals (16:1–17), and covenantal renewal (29:9–14), among other rituals and ceremonies that address the perils of community disarticulation and separation from kinship groups by reinforcing the kinship experienced as a community and people of Jehovah. The Lord’s same compassionate encouragement for favorable treatment of marginalized strangers and their inclusion into society, meant to be echoed by Israel and Judah, is reflected in the messages of Isaiah (Isaiah 56:1–7), Jeremiah (Jeremiah 7:6–7; 22:1–3), Ezekiel (Ezekiel 22:7, 29; 47:22–23), and Zechariah (Zechariah 7:9–10).

Both the Bible and archaeology illustrate efforts by Hezekiah to promote unity between Israelites and Judahites by centralizing religion and commemorating the Passover, a foundational event in the history of the house of Israel. Second Chronicles 30 relates the invitation made by Hezekiah to Israelites from the Galilee and tribal territories of Manasseh and Ephraim to celebrate Passover in Jerusalem. Although only some from Asher, Manasseh, and Zebulun attended (2 Chronicles 30:11), northern Israelites, Judahites, and resident aliens (displaced persons) from both kingdoms were united in observance of Passover. Hezekiah ordered the ruin of locations used for fertility rituals; closed and desecrated shrines/

While Hezekiah, the Judahite administration, and probably Jerusalem’s populace attempted to lessen the risks and dangers felt by the Israelite refugee population as they integrated into Judahite society, a lesson can be learned from the construction of the Broad Wall on the Western Hill. As a royal project aimed at enclosing the Western Hill and protecting the vulnerable population living outside the fortification walls of the Eastern Hill, the construction of the Broad Wall, which would have provided employment and subsistence through redistributed foodstuffs, appears to be a noble endeavor. The same can be said for the cutting of the Siloam Tunnel and the diversion of the Gihon Spring runoff to a collecting pool within the city walls. However, both the wall and the tunnel resulted in the marginalization of those whom the projects benefited. The Broad Wall bisects several eighth-century-BC dwellings, with some houses intentionally in-filled to provide a foundation for the wall. The need to build this fortification “with sufficient urgency to sacrifice the houses in its way”[64] is reflected in Isaiah 22:9–11, in which the prophet chastises the leadership and people of Jerusalem: “Ye have seen also the breaches of the city of David, that they are many: and ye gathered together the waters of the lower pool. And ye have numbered the houses of Jerusalem, and the houses have ye broken down to fortify the wall. Ye made also a ditch between the two walls for the water of the old pool: but ye have not looked unto the Maker thereof, neither had respect unto him that fashioned it long ago.”

Isaiah clearly identified the primary problem with the Judahite leadership and people—namely, their preoccupation with physical preparations rather than trusting in the Lord and focusing on their covenant relationship by looking to and having respect for the One who made the water and the stone.[65] Biblical scholar John N. Oswalt notes, “[The Judahites] congratulate themselves that they are not corrupt as the northern kingdom of Israel had been, and so they believed they have survived because of their merits when Israel fell. But Isaiah and the other prophets see clearly that all the same trends are at work in Judah that so tragically affected Israel.”[66] Those trends include pride, neglect of the marginalized such as the widow, orphan, and displaced persons, and lack of faith in the Lord to provide and protect the covenantal people. Additionally, we can see the concern of the prophet and the danger in neglecting or ignoring the considerations of those living on the Western Hill whose houses were “broken down to fortify the wall” and who cut the water conduit—in both cases, likely Israelite refugees. Thus, while the Broad Wall and the Siloam Tunnel were beneficial to the populace of Jerusalem, concern for those displaced by building the wall should have been exercised together with a faith in the Lord.

An additional lesson can be garnered from the experience of King Ahaz of Judah and his willingness to initiate a vassal treaty with the Assyrian Tiglath-pileser III, with its accompanying loyalty oath. Loyalty to Assyria came with a temporal price of a yearly tribute but also a spiritual price of trusting Assyria to fight their battles rather than relying on faith in Jehovah. Frequent journeys to Assyria to pay tribute by Israelite and Judahite emissaries who saw, experienced, and communicated the Assyrian royal ideology and propaganda to their home countries may have precipitated the prophetic counsel to not place political trust in Assyria or other temporal kings and kingdoms.[67] The prophets Hosea and Isaiah cautioned against and condemned Israel and Judah for making alliances with Assyria. Hosea warned that Assyria would not cure their wounds or provide for them (Hosea 5:13; 14:2–3), and Isaiah prophesied that Assyria would overwhelm Judah (Isaiah 8:6–8, 11–13) and would eventually be judged for its own arrogance (Isaiah 10:5–19).

Conclusion

Exploring the fall of the northern kingdom of Israel, the migration of refugees to Judah, and the efforts of the Judahite administration to integrate the two populations provides lessons from the past for our present. The study of the Israelite refugee migration as a result of the fall of Israel to the Assyrian empire originated in biblical studies as a means of explaining northern Israelite views in the Hebrew Bible, which was primarily written, compiled, and redacted by southern Judahites. Later, archaeologists looked to Israelite refugees to explain the growth of Judah and Jerusalem toward the end of the eighth century BC. The archaeology of Iron Age refugees in Jerusalem complements the witness and message of the Bible and the instruction of Church authorities regarding the treatment of dispossessed and vulnerable children of God.

In addition to the message for the population of Judah and its leadership to trust in the Lord rather than on their labor-intensive preparations (which overlooked the needs of the poor) in the face of overwhelming odds, the main lesson that the experience of the Israelite refugees teaches is the importance of unity to avoid marginalization and community disarticulation. As part of the family of God, we should strive to include those who have lost their connections to a homeland, employment, or family. Talents should be recognized and encouraged to better the community of God and further the work of the kingdom. Most importantly, respect and inclusion may rebuild familial bonds that are weakened or severed. In the October 2018 general women’s session, President Dallin H. Oaks related a story about a bullied refugee and noted that such “meanness” was “a tragic experience and expense to one of the children of God.”[68] His counsel to reach out in kindness and be loving and considerate is timely for all who interact with vulnerable persons.

Efforts by the Judahites to foster a unity between “strangers” living among them may not be explicitly evident in the archaeological record of Judah or in the biblical text, but the use of Israelite labor to create the Siloam Tunnel and the Broad Wall, seal impressions and ostraca with Israelite names, and Hezekiah naming his son Manasseh all strongly suggest ways that the Judahites incorporated refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel into the administration, labor force, and society of Judah. Likewise, efforts to care for refugees and integrate them into the community can be part of the legacy for modern believers and fellow children of God. President Russell M. Nelson taught, “Making a conscientious effort to care about others as much as or more than we care about ourselves” is a source of joy. By following the teachings of the Old Testament to open our hands to the poor and needy, including refugees (Deuteronomy 15:11), believers can actively live out their commitment to the two great commandments (Matthew 22:37–39).[69]

Notes

[1] This number includes 26 million refugees, 45.7 million internally displaced people, and 4.2 million asylum-seekers; see https://

[2] See Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Two Principles for Any Economy,” Ensign, November 2009, 55–58; Uchtdorf, “The Gift of Grace,” Ensign, May 2015, 107–10.

[3] Linda K. Burton, “I Was a Stranger,” Ensign, May 2016, 13–15; Patrick Kearon, “Refuge from the Storm,” Ensign, May 2016, 111–14.

[4] Russell M. Nelson, “The Second Great Commandment,” Ensign, November 2019, 99; see https://

[5] Tiglath-pileser III (Akkadian Tukultī-apil-Ešarra, meaning “my trust is in the son of the Ešarra”) was the throne name of an Assyrian general originally named Pulu who carried out a successful coup to become the Assyrian king. The biblical narrative states that Menahem, the king of Israel, paid tribute as a vassal to the Assyrian king, named Pul in Lo. This same Assyrian king, later called Tiglath-pileser in the Bible, campaigned against the Israelite king Pekah, conquering the region of the Galilee and “carr[ying] them captive to Assyria” (2 Kings 15:29).

[6] K. Lawson Younger Jr., “The Deportations of the Israelites,” Journal of Biblical Literature 117 (1998): 211, 218.

[7] Magen Broshi, “The Expansion of Jerusalem in the Reigns of Hezekiah and Manasseh,” Israel Exploration Journal 24 (1974): 21n2; burials in the Iron Age were located outside city boundaries because of the smell and other practicalities of burials; besides, the presence of tombs within the city would render the area ritually unclean.

[8] Nahman Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1983), 31–45.

[9] Nahman Avigad, “Excavations in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City, 1969–1971,” in Jerusalem Revealed: Archaeology in the Holy City, 1968–1974, ed. Yigael Yadin (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1975), 44.

[10] The impressions of the royal seals contain the Hebrew word lmlk, “belonging to the king,” with either a four- or two-winged solar disk or scarab, and the town names of either Hebron, Ziph, Socoh, or a center not found in the Bible called Mmst.

[11] Vocalization by the author. The phrase as written on the ostracon is [-l] qn ’rṣ; see Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem, 41. The reconstruction of ’Ēl at the beginning is based on this same epithet for God being used by Melchizedek (Genesis 14:19) and associated with Jehovah by Abraham (Genesis 14:22).

[12] Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem, 41–44.

[13] Broshi, “Expansion of Jerusalem,” 23–24. Some population estimates are as high as 40,000–120,000 people for all of Judah at this time; see J. Edward Wright and Mark Elliott, “Israel and Judah under Assyria’s Thumb,” in The Old Testament in Archaeology and History, ed. Jennie Ebeling, J. Edward Wright, Mark Elliott, and Paul V. M. Flesher (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2017), 448. In terms of settled area, archaeologist Israel Finkelstein estimates that the city grew from ten hectares to sixty hectares in the mid to late eighth century BC; see Israel Finkelstein, “Migration of Israelites into Judah after 720 BCE: An Answer and an Update,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 126 (2015): 197.

[14] Broshi, “Expansion of Jerusalem,” 23. This view is supported by later publications; see Magen Broshi and Israel Finkelstein, “The Population of Palestine in Iron Age II,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 287 (1992): 51–52; and Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts (New York: Touchstone, 2002), 243.

[15] Some scholars have argued for a more gradual growth in the eighth century BC, either supplemented by a limited number of refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel or totally devoid of refugees entirely.

[16] Finkelstein, “Migration of Israelites,” 200–201.

[17] Finkelstein, “Migration of Israelites,” 196. This would correspond with the rise in olive pollen in the eighth century BC present in the palynological record; see George A. Pierce, “Environmental Features,” in The T&T Clark Handbook of Food in the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel, ed. Janling Fu, Cynthia Shafer-Elliott, and Carol Meyers (London: Bloomsbury, 2021), 1–31.

[18] Wright and Elliott, “Israel and Judah,” 449. Later, as a result of the campaign of the Assyrian king Sennacherib against Judah in 701 BC that destroyed forty-six walled cities and villages and devastated the countryside, the number of rural villages and farmsteads in the Shephelah decreased from 250 to 85, and the rural population of Judah shifted as these internal refugees moved within the kingdom of Judah to sites in the Judean wilderness and Negev. See Israel Finkelstein, “The Archaeology of the Days of Manasseh,” in Scripture and Other Artifacts: Essay on the Bible and Archaeology in Honor of Philip J. King, ed. Michael D. Coogan, J. Cheryl Exum, and Lawrence E. Stager (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1994), 173. See also Israel Finkelstein, “The Settlement History of Jerusalem in the Eighth and Seventh Centuries BC,” Revue Biblique 115 (2008): 512–13.

[19] Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 457–58.

[20] Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem, 46–49.

[21] Avigad, “Excavations in the Jewish Quarter,” 43–44.

[22] Avigad, Discovering Jerusalem, 57–59.

[23] Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 484.

[24] K. Lawson Younger Jr., “The Siloam Tunnel Inscription,” in The Context of Scripture, vol. 2, Monumental Inscriptions from the Biblical World, ed. William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger Jr. (Leiden: Brill, 2003), 145–46 (COS 2.28).

[25] In examining possible reasons for the growth of Jerusalem in the eighth century BC, archaeologist Aren Maeir summarizes the arguments used against an influx of refugees from the northern kingdom of Israel; see Aren M. Maeir, “The Southern Kingdom of Judah: Surrounded by Enemies,” in Old Testament in Archaeology, 399.

[26] Nadav Na’aman, “When and How Did Jerusalem Become a Great City? The Rise of Jerusalem as Judah’s Premier City in the Eighth–Seventh Centuries B.C.E.,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 347 (2007): 24–27; see also Na’aman, “The Growth and Development of Judah and Jerusalem in the Eighth Century BCE: A Rejoinder,” Revue Biblique 116 (2009): 321–35; and Avraham Faust, “The Settlement of Jerusalem’s Western Hill and the City’s Status in Iron Age II Revisited,” Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 121 (2005): 97–118.

[27] Na’aman, “Growth and Development of Judah and Jerusalem,” 324. Na’aman also claims that the same ceramic forms and styles were used from ca. 800 BC to 586 BC; see Nadav Na’aman, “Dismissing the Myth of a Flood of Israelite Refugees in the Late Eighth Century BCE,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 126 (2014): 9. However, this stance clashes with the detailed pottery study in Joe Uziel, Salome Dan-Goor, and Nahshon Szanton, “The Development of Pottery in Iron Age Jerusalem,” in The Iron Age Pottery of Jerusalem: A Typological and Technological Study, ed. D. Ben-Shlomo (Ariel: Ariel University Press, 2019), 59–102.

[28] Na’aman, “Rise of Jerusalem,” 29. He bases his argument on the actions of the king of Cush (a kingdom south of Egypt in modern Sudan); this king extradited the king of Ashdod, who had rebelled against the Assyrian king Sargon II. However, Na’aman fails to distinguish between migrant refugees and a rebellious king seeking exile during a revolt.

[29] Na’aman, “Rise of Jerusalem,” 37.

[30] Na’aman, “Growth and Development of Judah and Jerusalem,” 325.

[31] Na’aman, “Growth and Development of Judah and Jerusalem,” 323.

[32] Joe Uziel and Nahshon Szanton, “New Evidence of Jerusalem’s Urban Development in the 9th Century BCE,” in Rethinking Israel: Studies in the History and Archaeology of Ancient Israel in Honor of Israel Finkelstein, ed. O. Lipschits, Y. Gadot, and M. J. Adams (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2017), 429–39.

[33] Finkelstein, “Settlement History of Jerusalem,” 502.

[34] Egon F. Kunz, “The Refugee in Flight: Kinetic Models and Forms of Displacement,” International Migration Review 7 (1973): 131–32.

[35] Na’aman, “Growth and Development of Judah and Jerusalem,” 323; see also Na’aman, “Dismissing the Myth,” 5.

[36] Na’aman’s examples date from either long before the period (e.g., Hittite treaties from the fifteenth to the fourteenth century BC) or from the reign of the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal in the seventh–sixth centuries BC. See Na’aman, “Rise of Jerusalem,” 31–35.

[37] The Vassal Treaty of Esarhaddon does have injunctions against treason, open rebellion, and supporting those involved with such activities, but the descriptions of treason (secretly plotting an overthrow of the crown) or rebellion and insurrection (openly fighting against Assyria) do not suggest any connection to a migrant refugee population fleeing from an Assyrian campaign. See Simo Parpola and Kazuko Watanabe, “Esarhaddon’s Succession Treaty,” in Neo-Assyrian Treaties and Loyalty Oaths, State Archives of Assyria 2 (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1988), http://

[38] Shawn Z. Aster, “An Assyrian Loyalty-Oath Imposed on Ashdod in the Reign of Tiglath-Pileser III,” Orientalia 87 (2018): 275–76.

[39] See COS 2.117C for the Assyrian account of Israelite tribute. The process of an emissary delivering tribute and accepting vassal status is detailed in Shawn Z. Aster, “Israelite Embassies to Assyria in the First Half of the Eighth Century,” Biblica 97 (2016): 175–98.

[40] Aster, “Israelite Embassies to Assyria,” 197. The Assyrian royal ideology consisted of the religious legitimacy of the king as leader of the worship of Ashur, the king as the military leader who would expand the empire, the universal nature of the empire, and the doctrine of Assyrian invincibility. These ideas were communicated by the Assyrians in wall reliefs, stelae, rock art carved into cliffs, sculptures, and seals.

[41] Na’aman, “Rise of Jerusalem,” 37.

[42] Anat Mendel-Geberovich, Ortal Chalaf, and Joe Uziel, “The People behind the Stamps: A Newly Founded Group of Bullae and a Seal from the City of David, Jerusalem,” Bulletin of ASOR 384 (2021): 159–82.

[43] Joan Comay, Who’s Who in the Old Testament (New York: Bonanza Books, 1980), 40–43, 260.

[44] The full Israelite name would have been “Shebnayau”; see Christopher B. Hays, “Re-Excavating Shebna’s Tomb: A New Reading of Isa 22, 15–19 in Its Ancient Near Eastern Context,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 122 (2010): 558–75.

[45] William M. Schniedewind, How the Bible Became a Book: The Textualization of Ancient Israel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 69.

[46] Schniedewind, How the Bible Became a Book, 95.

[47] Subsequent migrations of northern Israelites may have consisted of an acute movement of people who were non-elite and less literate.

[48] Schniedewind, How the Bible Became a Book, 94.

[49] Aaron A. Burke, “An Anthropological Model for the Investigation of the Archaeology of Refugees in Iron Age Judah and Its Environs,” in Interpreting Exile: Displacement and Deportation in Biblical and Modern Contexts, ed. Brad E. Kelle, Frank R. Ames, and Jacob L. Wright (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2011), 46.

[50] Gary A. Rendsburg and William M. Schniedewind, “The Siloam Tunnel Inscription: Historical and Linguistic Perspectives,” Israel Exploration Journal 60 (2010): 191.

[51] Rendsburg and Schniedewind, “Siloam Tunnel Inscription,” 198–99.

[52] Aaron A. Burke, “Coping with the Effects of War: The Archaeology of Refugees in the Ancient Near East,” in Disaster and Relief Management, ed. Angelika Berlejung (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2012), 277.

[53] Finkelstein, “Settlement History of Jerusalem,” 509; see also Finkelstein, “Migration of Israelites,” 202–3.

[54] Three examples were recently found near the Armon Hanatziv Promenade in Jerusalem in what was likely a royal or elite building; see Tzvi Joffre, “Davidic Dynasty Symbol Found in Jerusalem: Once in a Lifetime Discovery,” Jerusalem Post, September 3, 2020.

[55] Philippe Guillaume, “Jerusalem 720–705 BCE: No Flood of Israelite Refugees,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament 22 (2011): 197.

[56] Burke, “Anthropological Model,” 43.

[57] Burke, “Anthropological Model,” 50.

[58] Burke, “Coping with the Effects of War,” 281.

[59] Burke, “Anthropological Model,” 49.

[60] Finkelstein, “Settlement History of Jerusalem,” 507.

[61] The laws regarding strangers appear in Deuteronomy 1, 5, 10, 14, 16, 23–24, and 26–29; for a treatment of the gēr and their inclusion as part of the family of Israel and Jehovah, see Mark R. Glanville, Adopting the Stranger as Kindred in Deuteronomy (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2018).

[62] The prime example of a gēr gleaning is found in the story of Ruth gleaning in the field of Boaz during the cereal harvest (Ruth 2:1–17). Additionally, although they are not displaced persons, the actions of Jesus’s disciples eating grain from a field is justified under the same Deuteronomic provision (Matthew 12:1).

[63] Schniedewind, How the Bible Became a Book, 94.

[64] Dan P. Cole, “Archaeology and the Messiah Oracles of Isaiah 9 and 11,” in Scripture and Other Artifacts, 64.

[65] The use of second person plural verbs throughout Isaiah 22:9–11 indicates that the prophet is not addressing a particular person but a group of people, which likely included the population of Jerusalem as a whole and their leadership, such as the royal steward Shebna, who received condemnation later in the same chapter (Isaiah 22:15–19). See Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York: Doubleday, 2000), 333–34.

[66] John N. Oswalt, The NIV Application Commentary: Isaiah (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003), 269.

[67] Aster, “Israelite Embassies to Assyria,” 194–97.

[68] Dallin H. Oaks, “Parents and Children,” Ensign, November 2018, 67.

[69] Nelson, “The Second Great Commandment,” 100.