Introduction

Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith, “Introduction,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), vii-xvi.

Before he traveled to Carthage, Illinois, in late June 1844 to surrender on an arrest warrant, Joseph Smith called William Clayton, a trusted clerk, to his side. Less than three months earlier, Joseph Smith had formed a confidential council consisting of roughly fifty men. The council, which became known as the “Council of Fifty” or “Kingdom of God,” was established to “look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.” Furthermore, Joseph Smith had told them, the council “was designed to be got up for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”[1] The members of the council believed that it would protect the political and temporal interests of the Church in anticipation of the return of Jesus Christ and his millennial reign.

Now, shortly before going to Carthage, he instructed Clayton to destroy or hide the records of the council. Joseph Smith feared that the candid discussions within the Council of Fifty—including the desire to establish a theocracy—could be used against him in either a court of law or, more likely, the court of public opinion. Clayton opted to bury the records in his garden.

A few days after Joseph Smith was killed by a mob in Carthage, Clayton dug up the records of the Council of Fifty. He then copied the minutes of the council’s meetings into more permanent record books and continued taking minutes after Brigham Young reassembled the Council of Fifty in February 1845. Over the next year, the council met to discuss how to govern the city of Nauvoo after the state of Illinois revoked its municipal charter and how to find a settlement place for the Latter-day Saints in the West. The council’s final meetings in Nauvoo occurred in the partially completed Nauvoo Temple in January 1846, just a few weeks before the Saints began to cross the frozen Mississippi on their way west.

As they headed west, Church leaders took the minutes of the council meetings with them. The council met for periods of time in Utah Territory under Brigham Young and then under his successor, John Taylor. At some point, the records of the council became part of the archives of the Church’s First Presidency.

Historians have long known of the existence of the council and the minutes of its meetings. Until recently, though, the minutes had never been made available for historical research. Because of their inaccessibility—and because historians knew that they were made during a critical and controversial era of Mormon history—a mystique grew up surrounding the minutes. What did they contain? Why had they been withheld? Some speculated that the council’s minutes must contain explosive details about the final months of Joseph Smith’s life or the initial era of Brigham Young’s leadership of the Church. Indeed, the minutes had become a sort of “holy grail” of early Mormon documents.

Other records regarding the council’s activities are likewise scarce. Members of the council took an oath of confidentiality when they joined, meaning that many members left no records that discussed the council. Nevertheless, some members later spoke about the council publicly and others left private records in journals and letters. Over the past several decades, these additional records have allowed several scholars—especially Klaus J. Hansen, D. Michael Quinn, Andrew F. Ehat, and Jedediah S. Rogers—to gain an understanding of the Council of Fifty. While they each made important contributions, lack of access to the core minutes meant that their scholarship remained tentative, as each recognized.[2]

Since the beginning of the Joseph Smith Papers Project in the early 2000s, project leaders have emphasized that the papers will contain a comprehensive edition of all of Smith’s papers, published in print, online, or both. Many outside the project initially wondered if that would include documents that had previously not been made accessible to scholars. The first major indication that the edition would truly be comprehensive was the publication of one of Joseph Smith’s manuscript revelation books, called the Book of Commandments and Revelations, that had been part of the collection of the Church’s First Presidency and had never before been made available.[3] Still, historians questioned whether the project would ever publish the minutes of the Council of Fifty.

The minutes had never been previously available for at least two key reasons: first, because they were considered confidential during the council’s meetings, and later stewards of the records wished to honor that confidentiality; and second, because once they were in the possession of the First Presidency, they were seldom used or read by Church leaders, and there was no pressing reason to make them available. The Church’s commitment to publish all of Joseph Smith’s documents as part of The Joseph Smith Papers provided the appropriate moment for their release.

We had the privilege of being involved with preparing the minutes for publication. In fall 2012, Matthew J. Grow was asked by Reid L. Neilson, managing director of the Church History Department, to study a transcript of the Council of Fifty minutes and—with the assistance of Ronald K. Esplin, a general editor of the Joseph Smith Papers—to write an introduction to the minutes that would help inform Church leaders regarding their contents.

Several months later, we learned that the First Presidency had granted permission to use the council’s minutes in the publication of Joseph Smith’s final journals (the third volume of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers). This volume was nearly complete, but we had put publication on hold pending this decision because the journal refers to the Council of Fifty and we hoped to use insights from the minutes in our annotation. Significantly, the First Presidency also granted permission to publish the council’s minutes as a separate volume in The Joseph Smith Papers.

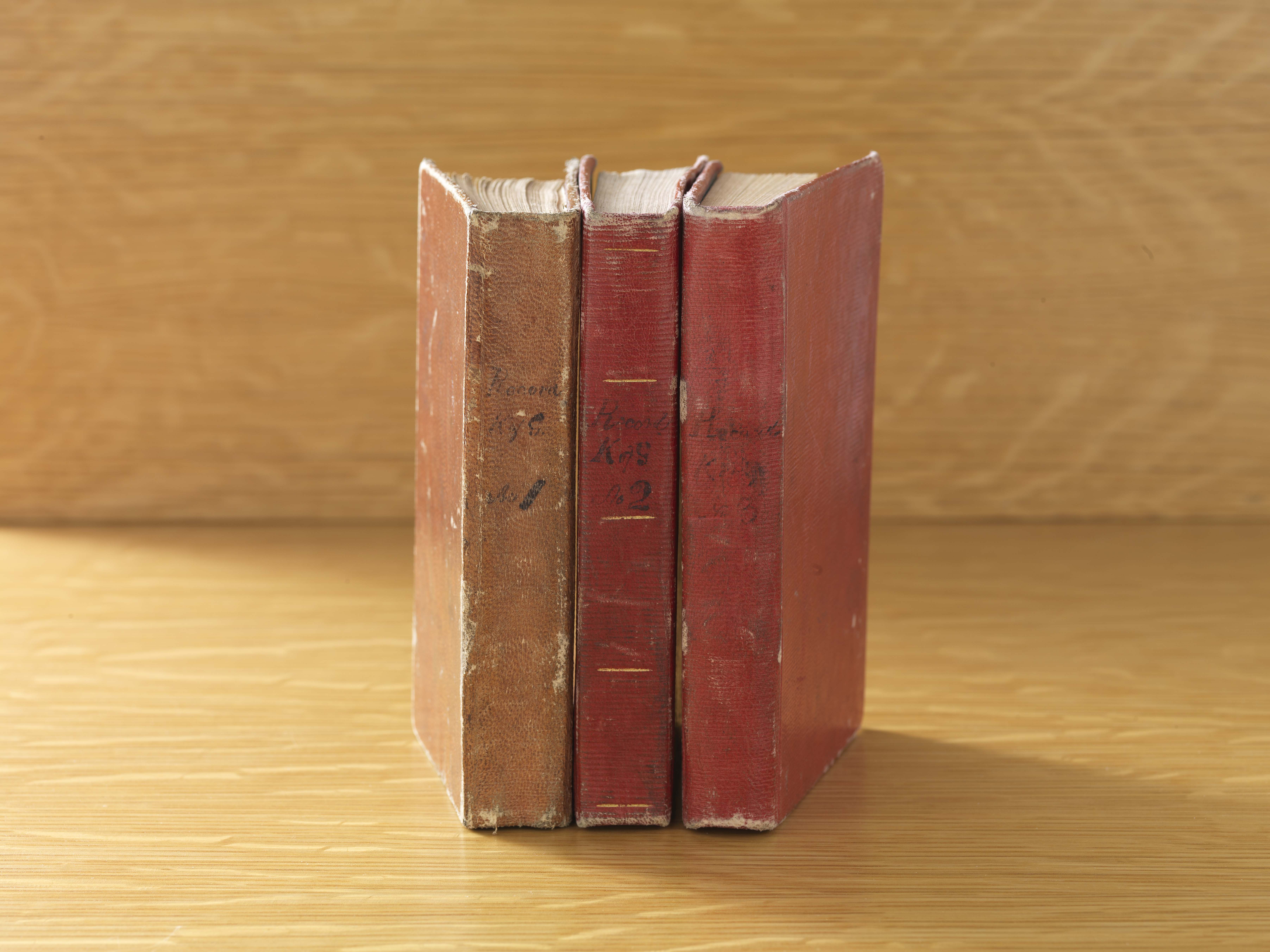

These three small record books contain William Clayton's minutes of the Nauvoo Council of Fifty. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

These three small record books contain William Clayton's minutes of the Nauvoo Council of Fifty. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

After project leaders learned this news, they assembled a meeting of the staff of the Joseph Smith Papers Project on May 1, 2013. At the meeting, Elder Steven E. Snow, Church Historian and Recorder, announced the decision to the jubilation of the staff. We were then allowed to see and hold the three small record books that contained the council’s minutes in the distinctive handwriting of William Clayton. As historians and editors who had long studied the Council of Fifty and hoped that the minutes would be included in The Joseph Smith Papers, this was a remarkable meeting. Eric Smith recorded in his journal that evening, “This is a day long anticipated by Mormon historians: the opportunity to publish these minutes, which the world has known about for a long time and which critics of the Church have often conjectured contain material that will embarrass the Church. I feel privileged to be involved with this project and to be one of the few people who has seen these minutes.”

We were asked to keep the decision confidential until a public announcement was made. Notwithstanding our collective excitement, we honored the request not to talk about the prospective publication of the minutes until Elder Snow made a public announcement in an interview with the Church News in September 2013.[4] Following the public announcement, we could talk more freely about our work on the minutes.

After the permission came, we quickly assembled a team of historians, led by Grow. Ronald K. Esplin brought his deep knowledge about both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young to the task. Mark Ashurst-McGee, who had written a dissertation on early Mormon political thought, added perspective on those issues and did the final textual verification. Gerrit J. Dirkmaat’s dissertation had likewise probed a relevant topic: the relationship between the Mormons and the United States between 1844 and 1854. Finally, Jeffrey D. Mahas brought his indefatigable research skills and archival sensibilities to the task. Most of us were working on other projects simultaneously with the Council of Fifty minutes, but all of us were thrilled to have a part in writing the introductions and footnotes that would be published along with the minutes. Historians generally love working with documents that haven’t been used much by scholars previously. But the council minutes were something else entirely: a document not only made newly available, but one that had been the subject of tremendous speculation and contained critical information on early Mormon thought and governance.

The volume editors listed on the cover page were, however, only a small part of the team at the Joseph Smith Papers Project who assisted with the publication of the minutes. Eric Smith led the editorial team that helped transcribe the minutes and verify their text, meticulously checked the thousands of sources used in the annotation, edited and then edited and edited again the introductions and footnotes, selected images, performed genealogical research, designed maps, and helped promote the book. Among the roughly two dozen individuals who assisted with such work were Rachel Osborne, source checker; Shannon Kelly, editor; Kay Darowski and Joseph F. Darowski, text verifiers; Jeffrey G. Cannon, photoarchivist; Ed Brinton and Alison Palmer, typesetters; and Kate Mertes, indexer.

As we began talking about the council’s minutes publicly in anticipation of their 2016 publication, we learned that notwithstanding the mystique the Council of Fifty had gained among the historical community and the importance of the council to early Latter-day Saints, the organization itself is little known among modern Latter-day Saints. The Mormon tendency to use numbers to name quorums and councils did not help matters. “Do you mean the Council of Seventy?” many wondered. The lack of knowledge is not particularly surprising; while a few scattered references to the Council of Fifty have appeared in the Church’s magazines in the past several decades, the council has not received much other official attention from the Church.[5] For instance, the Church’s study manual Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith does not contain any references to the council.

While the council’s minutes are very readable—containing as they do relatively complete records of discussions, debates, and decisions—we knew that most individuals interested in Mormon history and theology would simply not have the time or inclination to wade through the nearly eight hundred pages in the published Joseph Smith Papers volume to gain an understanding of the Council of Fifty.

In addition, we were convinced that the council’s minutes needed to be engaged by scholars to evaluate the question of how these minutes should change our collective understanding of the Latter-day Saint past. The minutes speak on a broad range of fascinating issues—Mormon thought on earthly and heavenly constitutions and government, Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign, the murder of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, Mormon relationships with American Indians, the transition to the leadership of Brigham Young, the response to the revocation of the Nauvoo charter, the completion of the Nauvoo Temple, dissent and vigilante violence in and around Nauvoo, Latter-day Saint thought on religious liberty, and the planning for the exodus west.

Furthermore, the minutes illuminate a crucial era in the Mormon past that has not received adequate attention from historians. Often, histories underemphasize the critical era between the two events often used as a shorthand to define this time period: the Martyrdom and the Trek West. The era between March 1844 and January 1846—or, roughly, between Joseph Smith’s murder and the Mormon exodus from Illinois—is a particularly important time of transition in Mormon history. The council’s minutes allow us an unprecedented window into the thinking of Latter-day Saints during this era, including their grand ambitions to establish the kingdom of God and fulfill prophecies from the Bible and Book of Mormon, their devastation at the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, their alienation and anger at the United States because of these murders and other persecution, and their determination to find a place of safety and refuge in western North America where they could build their kingdom in peace.

The minutes of the Council of Fifty shape historical understanding, not just of Mormon history but of larger events in US and international history. In the council’s deliberations—including over Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign and the past treatment of the Latter-day Saints—Smith and other members highlighted their views of the failure of the US Constitution and of federal, state, and local governments to adequately protect religious liberty. Under the government system of that time, the constitutional protections of religious liberty did not yet apply to state and local governments, and the Mormons believed that the tyranny of the majority had imperiled their liberty. In addition, the council’s minutes demonstrate the Mormons’ desire to potentially settle outside of the United States as they explored the independent Republic of Texas, California (then a part of Mexico), and Oregon (then disputed between Great Britain and the United States) as possible settlement sites. Mormons thus presented the US government with a geopolitical challenge, as they sought to establish settlements beyond the boundaries of the United States.

We asked each of the scholars in this volume to consider a question: How do the Council of Fifty minutes change our understanding of Mormon history? In other words, why do they matter? Three of the papers in this volume began as initial scholarly reactions—before the Council of Fifty minutes were published—at the Mormon History Association’s annual conference in June 2016. Two additional essays were presented at a conference at the University of Virginia at the launch of the publication of the minutes in September 2016. All of the essays are published here for the first time.

This volume opens with an essay by preeminent historian Richard Lyman Bushman, professor emeritus from Columbia University and biographer of Joseph Smith, who considers the broad ramifications of the minutes for Mormon history. Richard E. Turley Jr., who played a role in obtaining permission to publish the minutes during his time as Assistant Church Historian and Recorder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, examines one key context for the establishment of the council: violence against the Latter-day Saints, particularly in Missouri in the 1830s.

Several essays examine the three months that the council met under Joseph Smith in early 1844. Spencer W. McBride, an early American historian who works for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, demonstrates how the minutes shed new light on Joseph Smith’s campaign for the US presidency. The minutes also illustrate Joseph Smith’s thinking on the blending of theocracy and democracy, captured with the evocative term “theodemocracy,” as explored in the essay by Patrick Q. Mason, Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies at Claremont Graduate University. Benjamin E. Park, an assistant professor of history at Sam Houston State University, places the questions raised by the council in broader American political thinking. The essay by Nathan B. Oman, professor of law at William & Mary Law School, likewise contextualizes the council’s attempt to write a constitution in the milieu of US political thought and constitution-writing in the nineteenth century.

The next two essays look at the minutes broadly. Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University, highlights some of the most important statements in the minutes by Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Church leaders on topics ranging from religious liberty to friendship to how councils should operate. R. Eric Smith explores insights that the Council of Fifty minutes provide into broader Mormon record-keeping practices of that period.

The essays then transition to examine the council as it operated under Brigham Young from February 1845 to January 1846. The essay by Matthew J. Grow and Marilyn Bradford assesses what the Council of Fifty minutes demonstrate about Brigham Young’s personality, leadership style, and priorities as leader of the Latter-day Saints. Jeffrey D. Mahas, a documentary editor at the Joseph Smith Papers Project, examines one of the council’s key objectives: encouraging conversion of and exploring alliances with American Indians. As Matthew C. Godfrey, managing historian of the Joseph Smith Papers, discusses in his essay, the council took several steps to complete the Nauvoo House, a large boardinghouse in Nauvoo that the Saints had been commanded to build in a revelation to Joseph Smith.

Two essays then consider the role of the council in planning for the Saints’ exodus from Nauvoo. Disputes over where the Mormons should ultimately settle led to divisions within the Quorum of the Twelve and the Church, as Christopher James Blythe, a historian with the Joseph Smith Papers Project, discusses in his essay on apostle Lyman Wight. Richard E. Bennett, a leading expert on the Mormon exodus and professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University, then examines how the council’s minutes both confirm existing scholarship on the exodus and add new light.

The final two essays examine broad themes in the council’s history, particularly in the context of western US history. Jedediah S. Rogers, co-managing editor of the Utah Historical Quarterly and author of a book on the Council of Fifty that focuses on the Utah period, places the council in the context of history writing about the American West. In his concluding essay, W. Paul Reeve, professor of history at the University of Utah, reflects on the contributions of the minutes, including in highlighting the Mormons’ search for religious liberty in the West.[6]

As demonstrated by these essays, the Council of Fifty minutes provide crucial insights into Latter-day Saint history in these critical years. While historians already knew the broad outlines of much of what was discussed in the council, the minutes provide tremendous detail on the discussions and deliberations that led to the actions taken by Joseph Smith, Brigham Young, and other Mormon leaders during this time.

We hope that this collection of essays both increases public knowledge about the Council of Fifty and spurs future scholarship. Dissertations, articles, and books remain to be written on what the Council of Fifty meant to early Latter-day Saints and how the council’s minutes shed new light on a myriad of topics in early Mormon and US history.

Notes

[1] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11 and April 18, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 40, 128 (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[2] See Klaus J. Hansen, Quest for Empire: The Political Kingdom of God and the Council of Fifty in Mormon History ([East Lansing]: Michigan State University Press, 1967); D. Michael Quinn, “The Council of Fifty and Its Members, 1844 to 1945,” BYU Studies 20, no. 2 (Winter 1980): 163–97; Andrew F. Ehat, “‘It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth’: Joseph Smith and the Constitution of the Kingdom of God,” BYU Studies 20, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 253–80; and Jedediah S. Rogers, ed., The Council of Fifty: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2014).

[3] See Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Manuscript Revelation Books, facsimile edition, vol. 1 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2009).

[4] R. Scott Lloyd, “Newest Volume Published for the Joseph Smith Papers Project,” Church News, September 16, 2013.

[5] See, for instance, Donald Q. Cannon, “Spokes on the Wheel: Early Latter-day Saint Settlements in Hancock County, Illinois,” Ensign, February 1986, 62–68; Glen M. Leonard, “The Gathering to Nauvoo, 1839–45,” Ensign, April 1979, 35–42; Reed Durham, “What Is the Hosanna Shout?” in “Q&A: Questions and Answers,” New Era, September 1973, 14–15; and Ronald K. Esplin, “A ‘Place Prepared’ in the Rockies,” Ensign, July 1988, 6–13.

[6] The essays by Bushman, Reeve, and Bennett were first presented at the June 2016 MHA conference. The essays by Turley and Oman were first presented at the September 2016 University of Virginia conference. Several of these essays were then revised by their authors specifically for this compilation.