Insights into Mormon Record-Keeping Practices from the Council of Fifty Minutes

R. Eric Smith

R. Eric Smith, “Insights Into Mormon Record-Keeping Practices From the Council of Fifty Minutes,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 91-104.

R. Eric Smith is the editorial manager for the Publications Division, Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In that role, he edits print and web publications for the Church Historian's Press, including publications of the Joseph Smith Papers Project. He previously was an editor for the church's Curriculum Department, and before that he practiced law for a Salt Lake City firm.

I have been an editor and manager with the Joseph Smith Papers Project for more than a decade. The project’s publications fall into the well-established genre of documentary editing, meaning the focus is on presenting the texts of the original documents with the historical information needed to understand the circumstances of their creation. One of the major contributions of the project’s historians and archivists has been to shed light on the world of early Mormon record keeping, particularly with respect to the papers of Joseph Smith. Who inscribed and revised these documents, when, and in what capacity? For what purposes were the documents created? How do the documents relate to one another? How were the documents transmitted, used, filed, and preserved? How reliable are the documents? For documentary editors, the answers to these and similar questions can be as important as the content of the documents themselves.

As the other essays in this collection help demonstrate, the content of the recently published record of the Nauvoo Council of Fifty is invaluable in helping historians and others understand Mormon history from the late Nauvoo period to the exodus west and beyond. Council clerk William Clayton’s record is also fascinating when interrogated as a record—that is, through questions such as those listed above. My essay shares a few insights into and questions about Clayton’s record from the standpoint of a documentary editor.

Confidentiality of the Minutes

The life story of the minutes, from their initial creation by Clayton down to the present, is interesting in its own right, and I provide a brief summary here for that reason and to help introduce my other observations about them. A key element of the story is confidentiality. The members of the council took a confidentiality oath upon joining the council, and many council discussions reemphasized the importance of secrecy. Clayton evidently began keeping minutes on loose paper at the preliminary council meeting on March 10, 1844,[1] but the minutes of the initial March meetings were burned after the March 14 meeting out of fear they could be used against the members of the council. Nevertheless, Clayton continued keeping minutes after March 14. A few days before his death, Joseph Smith ordered Clayton to send away, burn, or bury the council records. Clayton buried them in his garden and dug them up a few days later—another Mormon record coming out of the ground.

It was apparently after this that Clayton began reconstructing the destroyed minutes and copying surviving loose minutes in the three bound volumes (sometimes referred to as the “fair copy,” meaning a neat and final copy) that survive today. When the council was revived in early 1845 under Brigham Young, a pattern was established of the loose minutes being read at the subsequent meeting and then burned. Clayton kept a permanent copy of the minutes in the bound volumes, but it is not clear if other members of the council even knew of the fair copy. After the exodus to Utah, the records and proceedings of the council continued to be closely guarded. For example, in December 1880, council recorder George Q. Cannon referred to the Council of “Kanalima” when he wrote about the council in a letter to Joseph F. Smith (“kanalima” is the Hawaiian word for “fifty”; both Cannon and Smith had been missionaries to Hawaii in their youth). Eventually, Clayton’s record became part of the First Presidency’s collection, where it remained closed to access until the twenty-first century.[2]

That the record was closed was obviously a challenge for the Joseph Smith Papers Project, which intended to publish a comprehensive edition of Joseph Smith documents and had repeatedly advertised that fact. The question of whether the project would publish these records was seen by some observers as a sort of acid test of the project’s credibility—if the project could not publish the Council of Fifty minutes, it could not claim to be transparent (much less comprehensive). Project scholars remained hopeful that permission to access and publish the Joseph Smith–era Council of Fifty records would be given. While for years we waited and hoped permission would come, we focused on producing an edition that both would satisfy high scholarly standards and would serve the Church’s interests in fostering reputable scholarship on the Church’s history. We also paused work for a period of time on the third volume of Joseph Smith’s journals, covering May 1843 through June 1844, because we wanted the annotation in that volume to be informed by the Council of Fifty minutes.[3] Eventually, in 2010, project scholars were given access to the records and permission to publish them.

The council minutes are one of several records from the First Presidency’s collection that have been made available to the project for either publication or research in the last dozen years. Other examples include Revelation Book 1 (or the “Book of Commandments and Revelations”), Joseph Smith’s first Nauvoo journal (contained in the record book titled “The Book of the Law of the Lord”), and three drafts of the early portion of Joseph Smith’s manuscript history project.[4]

It should be noted that the council minutes are not the only Joseph Smith record containing material that Joseph and his associates viewed as confidential. The early editions of the Doctrine and Covenants, for example, used code words in some revelations to conceal the identities of Church leaders involved with Church businesses.[5] In Joseph Smith’s Nauvoo journals, his scribe Willard Richards used shorthand to record especially sensitive information, such as information about plural marriages.[6] Richards also attempted to conceal certain aspects of council-related discussions in the journal by writing some words backward. In the March 10, 1844, entry, in which he summarized the initial meeting of the council, Richards wrote Texas as “Saxet,” Pinery as “Yrenip,” Santa Fe as “Atnas Eef,” and Houston as “Notsuoh.”[7] This code is about the simplest one imaginable, useful probably only to throw off someone who would take a quick glance at the journal.

To me, the recording and preservation of confidential information shows how serious Church clerks were about keeping records. Why else the paradox of writing down something that you want kept hid? Why not just avoid recording in the first place?

Importance of Keeping a Record

At the close of Clayton’s minutes for the council meeting on March 14, 1844, we find this surprising passage: “It was considered wisdom to burn the minutes in consequence of treachery and plots of designing men.”[8] Given that the council’s plans to improve upon the US Constitution and to explore settlements outside the nation’s boundaries could be seen as controversial, if not treasonous (and publicizing such plans could have led to interference with them), it makes sense that council members would want to keep their business confidential. Why then did Clayton keep minutes of those initial meetings in the first place? And—a more arresting question—after burning the earliest minutes, why did Clayton continue minute taking and then later reconstruct the discussions of those earliest meetings, even when Church leaders worried so much about keeping their discussions confidential?

The answer must be that Church leaders, or at least Clayton, had become thoroughly convinced of the importance or even vitality of record keeping—perhaps so much so that keeping records had moved to the level of habit. Of course, record keeping had been emphasized both explicitly and implicitly in the Church’s scripture. In the Book of Mormon, for example, Enos prays that the Nephite records will be preserved, and the resurrected Christ himself inspects the Nephite records and finds them deficient. In the revelation given the day the Church was organized, God commanded the Church to keep a record.[9] The fullest explication on the importance and purposes of record keeping had come from Joseph Smith in instructions he gave the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles shortly after the quorum was organized in February 1835. The oft-quoted passage is too long to be repeated here, but in it Joseph Smith gave a number of reasons that records should be kept: they would serve as precedent to help decide “almost any point that might be agitated”; they would help leaders more powerfully bear witness of the “great and glorious manifestations” that had been made known to them; leaders would later find passages of these records personally inspiring—“a feast” to their “own souls”; God would be angry and the Spirit would withdraw if leaders did not sufficiently value and preserve what God had given them; and if leaders were falsely accused of crimes, records would help prove that they were “somewhere else” at the time.[10]

While we can only guess as to whether particular members of the council had any of these objectives in mind with respect to the record Clayton was keeping (indeed, it is not clear that the members realized Clayton was copying his loose minutes into a bound record[11]), we get one more glimpse into Joseph’s views on the importance of records a few days before his murder. At about one o’clock in the morning on June 23, 1844, Joseph Smith, fearing for his safety in the crisis that erupted after the destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor, called for Clayton and gave him instructions. In his journal Clayton recorded, “Joseph whispered and told me either to put the r of k [records of the kingdom] into the hands of some faithful man and send them away, or burn them or bury them.”[12] Presumably, Joseph Smith feared the records might be used against him and other Saints. Even so, he gave Clayton the option to hide the records rather than to destroy them. At this point Clayton, as one historian observed, “trusted that calmer, more reasonable and more secure times would come for the Latter-day Saints and therefore preserved the records for future generations.”[13] In light of the importance that the Council of Fifty record has to understanding Mormon history, Clayton is a hero for deciding to preserve the records, even though doing so put him at personal risk.

Systematization of Record Keeping

In looking at Clayton’s record as a record, one of the first things we notice is that Mormon record keeping had become routinized. At the preliminary meeting of the Council of Fifty on March 10, 1844, Joseph Smith appointed William Clayton as clerk of the meeting.[14] Clayton apparently began keeping minutes that day, though, as noted above, the minutes of the earliest Council of Fifty meetings were later burned. The next day, when the council was officially organized, Joseph appointed Willard Richards as council recorder and Clayton as council clerk—Clayton was to take the minutes, and Richards perhaps had some supervisory role over Clayton. Both Richards and Clayton had significant prior experience in keeping Church records.[15]

Having two experienced clerks on the council meant that Clayton had a replacement scribe on standby if he couldn’t make a meeting. This may not have been the reason that Joseph Smith appointed both a recorder and a clerk to the council, but the redundancy of roles proved handy, as Richards evidently took the complete minutes of three meetings. He was presumably also the one who took up the pen for Clayton when he had to leave one meeting partway through with a toothache.[16]

Further evidence of the routinization of Church record keeping is the high quality of Clayton’s Nauvoo Council of Fifty record. His thorough, highly legible record is clearly the product of much time and care. Though Clayton presumably took original minutes on loose paper, he eventually began copying those minutes into bound volumes.[17] This process reflects awareness of broader Church record-keeping practices[18] and a consciousness to safeguard and preserve the record. As he copied the minutes, Clayton apparently used other available records, such as an attendance roll and original correspondence, to flesh them out.[19] This copying and expanding effort took considerable time and labor, as Clayton’s journal indicates.[20] Even the fact that the three volumes of Clayton’s record closely match one another in size and binding signals a maturing in Mormon record keeping.

We can see by comparison to earlier efforts how far the Church had come in systematizing its record-keeping practices. For example, Joseph Smith apparently did not begin copying loose manuscripts of revelations into a copy book until at least two years after he received his first revelation.[21] As another contrasting example, consider the document known by the Joseph Smith Papers as Minute Book 2, perhaps still better known as the Far West Record. This record book contains copies of minutes from Church meetings held as early as 1830 in New York, but the book as we have it was not begun until 1838 in Missouri—and was written by scribes different from those who kept the original minutes (indeed, some of the original scribes by that time had left the Church).[22] It seems probable that important information was lost as the minutes now copied into Minute Book 2 traversed this distance of time, place, and personality.

A Solitary Effort

Most of the significant Church record books from this period were created by a number of scribes working in sequence or sometimes together. For example, Joseph Smith’s second letterbook, created from 1839 through the summer of 1843, was inscribed by seven different clerks. Minute Book 2, created intermittently from 1838 through 1844, was inscribed by five different clerks, who copied minutes originally kept by about twenty different clerks. The first volume of Joseph Smith’s manuscript history, the only volume of that record completed before his murder, was inscribed by four clerks.[23] With these records, which were generally kept in Joseph Smith’s office, the work of one scribe was likely to be seen by another. This may have created a certain accountability as to what was recorded—and an expectation that what was recorded was not completely private.

In contrast, the Nauvoo Council of Fifty record as we have it was created by one scribe, working alone and apparently in private, William Clayton. Though loose minutes of one council meeting were read at the following meeting, there is no evidence that anyone other than Clayton saw the fair copy of the minutes until the Utah period—in fact, as noted above, other council members may not have even been aware of the fair copy. It is interesting to consider how these circumstances may have affected the way Clayton created the fair copy—did this spur him on, for example, in his effort to complete the fair copy, expecting that there would never be anyone else who could complete the record for the Nauvoo period if he did not?

In this vein, I raise another question that others may wish to explore. What can we learn by considering the Nauvoo Council of Fifty record not only as an institutional record but also as a personal record of William Clayton? What can we learn of his personality or biases, his views of what initiatives or positions were wise, his individual understanding of what the council was to accomplish? If nothing else, the triumph of the detail in and the mere existence of this record shows how valuable Clayton thought the minutes of the council were and would be.

Quality of Records

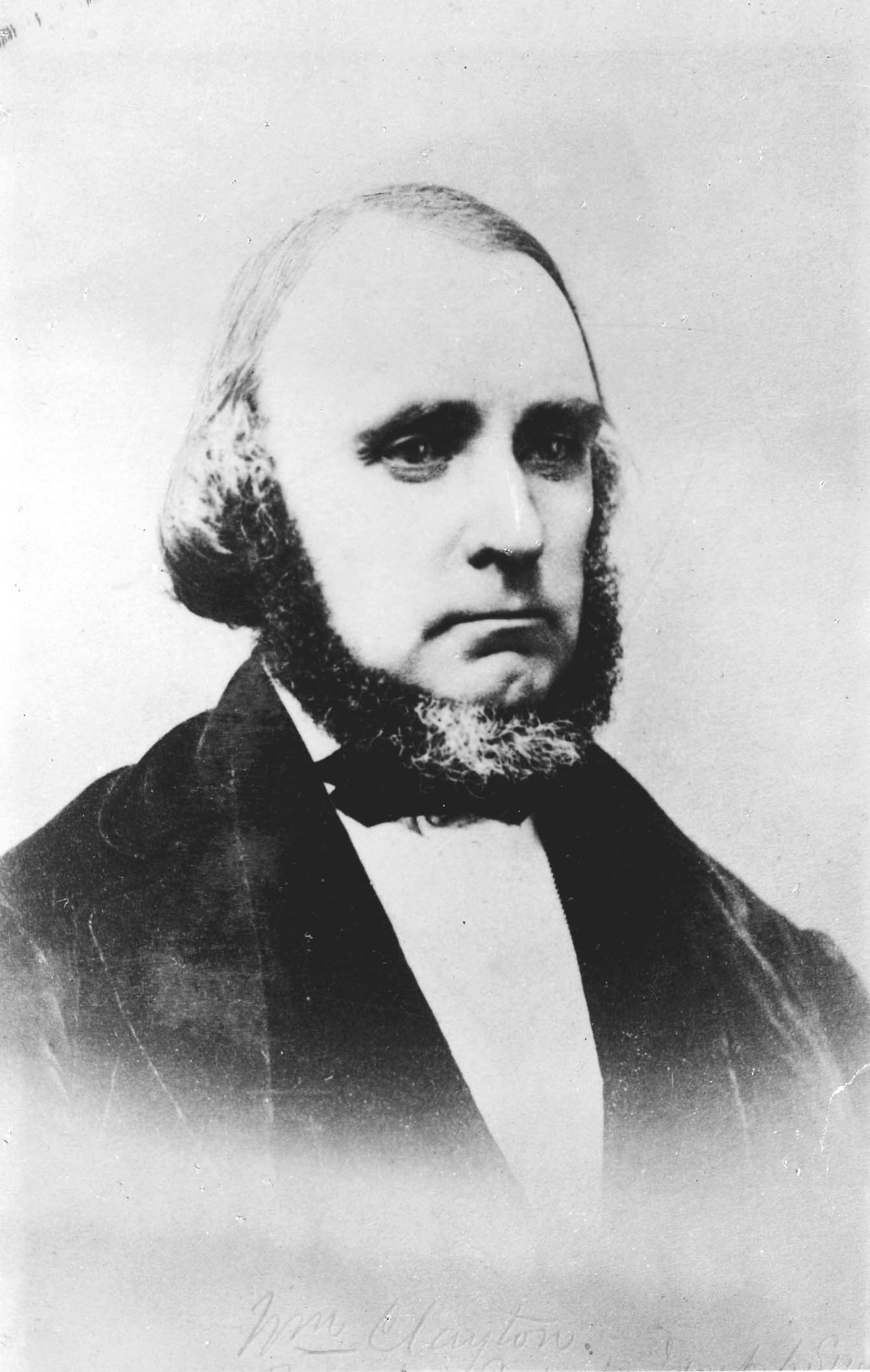

The nearly 900-page Council of Fifty record is entirely in the handwriting of council clerk William Clayton. Photograph circa 1855. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The nearly 900-page Council of Fifty record is entirely in the handwriting of council clerk William Clayton. Photograph circa 1855. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

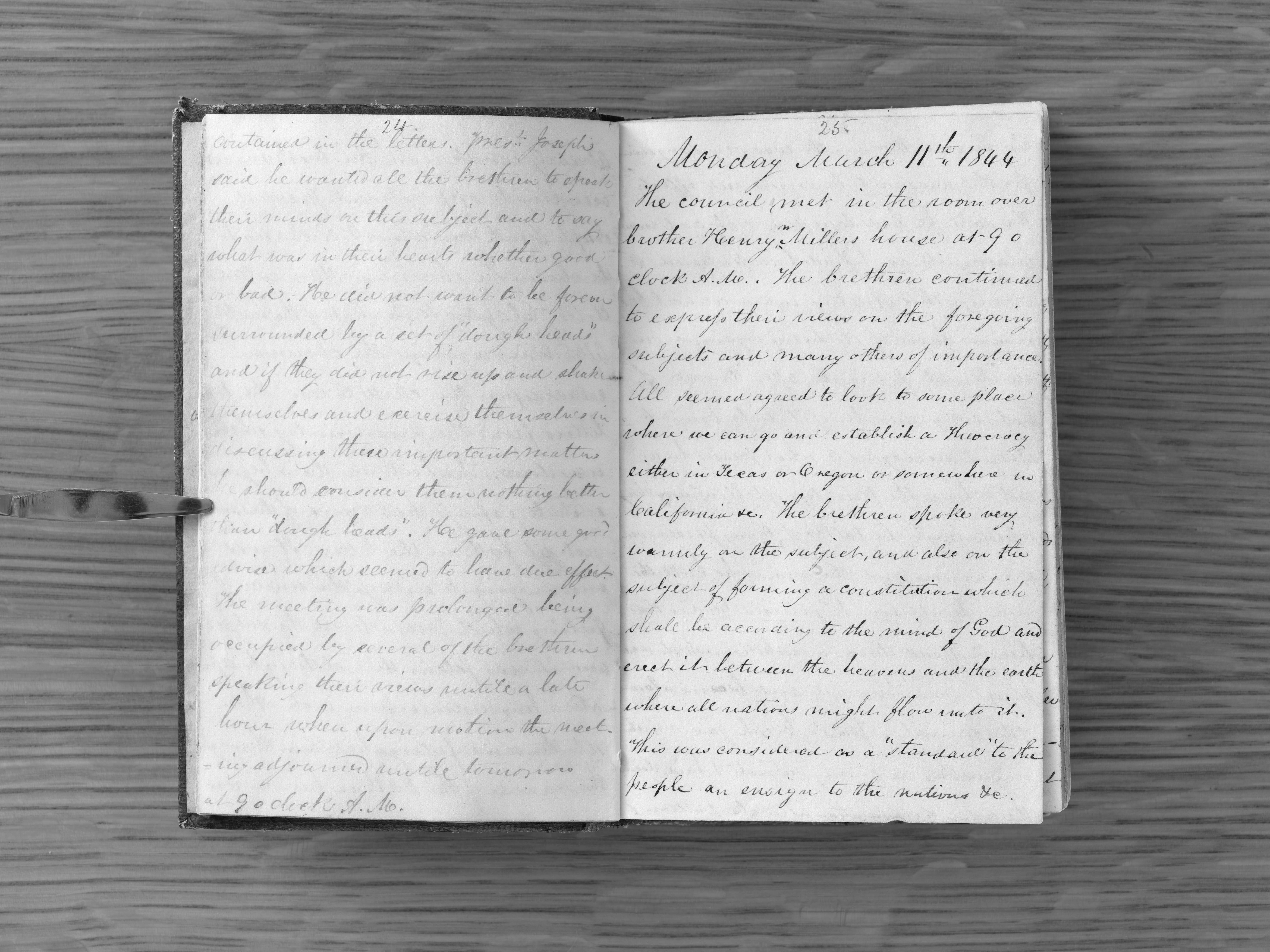

It is always interesting to consider how various circumstances influence the quality of a particular Mormon record from this period. Joseph Smith’s history notes that the deaths and faithlessness of some of his clerks, together with lawsuits, imprisonment, and poverty, had significantly interfered with the keeping of his journal and history.[24] With respect to the Council of Fifty record, it is painful to imagine how much detail from the record was lost when the minutes of the initial meetings were burned. The March 10, 1844, preliminary meeting convened at 4:30 p.m. and met until a “late hour,” with a break for dinner. And yet the minutes that Clayton reconstructed in fall 1844 are limited almost entirely to copying the two letters from the Wisconsin Saints. The pattern continues for the next few days of minutes. On March 11, the council met “all day,” but the minutes take up only three pages of the record. On March 12, the council apparently met in the evening, but the record has no report, apparently because Clayton had other business that day. On March 13, the council evidently met most of the day. Clayton’s report is two paragraphs. On March 14, the council met for about seven hours. Clayton: two paragraphs.[25] These meetings, held over five days straight, were the ones where two fairly innocuous letters (proposing the relocation of the Wisconsin branch to Texas) launched the formation of a new body that proposed to revise the US Constitution and that expected to “govern men in civil matters”![26] How did these men get from A to Z so quickly? The minutes here show the conclusions but so few of the reasons.

Finally, on March 19, the minutes start to become lengthier and more detailed, as now we have contemporary rather than reconstructed minutes. Even so, it is only during the period of Brigham Young’s chairmanship that the minutes become consistently detailed. It is not entirely clear what changed during Young’s administration, but Clayton did complain in the May 25, 1844, minutes that he could not take minutes “in full” because members were talking over one another.[27] This was after many council members had left to campaign for Joseph Smith’s presidential run, and when the outside opposition that would lead to the two murders a month later was reaching a fever pitch. The editors of the minutes also postulate that the minutes from the Young era may be fuller because Clayton copied his loose minutes closer to the times of the meetings being reported, meaning he could use his memory to flesh out his raw minutes.[28]

Humor in the Record?

The extant council members for March 10, 11, 13, and 14, 1844, were reconstructed in fall 1844 by William Clayton, based on journal entries, memory, and perhaps other records. Photographs by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The extant council members for March 10, 11, 13, and 14, 1844, were reconstructed in fall 1844 by William Clayton, based on journal entries, memory, and perhaps other records. Photographs by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

There is an example of humor in the Council of Fifty record that is worth noting, though we will never know if it was intentional.

In early 1845, a fairly obscure figure named William P. Richards wrote to council member George Miller proposing a “Mormon Reserve” (a dedicated area where Mormons would be confined) as a solution to the ongoing conflict between Mormons and their neighbors in Illinois. To me, Richards comes across as meddling, tedious, and a bit self-congratulatory. Council members expressed some initial interest in the proposal, though it is not clear that their interest was genuine. They may have only wanted to buy themselves more time to finish the temple. At one point in the correspondence between Richards and Miller, Richards gave permission that the exchanges be published in the newspaper but asked that the printer “guard against typographical errors.”[29] When Clayton hand copied the correspondence into the record, however, he misspelled a word, making Richards’s request a kind of joke on itself: “Please also gaurd against typographical errors.”[30] In the rest of the record, Clayton spells “guard” or “guarded” correctly about ten times, with no other misspellings. While the misspelling “gaurd” could have resulted from the mere slip of a pen, one wonders if Clayton felt a bit exasperated at Richards’s officiousness and decided to play a quiet trick on him.

Information about Other Records

The Council of Fifty record provides a treasure trove of information about records (in addition to the minutes themselves) that were created, received, or reviewed by the council. On its website, the project has published a comprehensive list of such records, totaling roughly six dozen items.[31] We see in the volume and variety of these records a Church leadership who are coming of age in using the written word or published records to share information, to try to persuade others, to seek advice, to make decisions, and to document their history.

Besides all that we can infer about Mormon record keeping from Clayton’s record, there is also some explicit commentary about the scope and purpose of the Church’s flagship record-keeping project of that time. In a council meeting on March 22, 1845, discussion ensued about what kind of information was appropriate to include in the manuscript Church history then being compiled (the history was published serially in Church newspapers and then by B. H. Roberts as History of the Church). Willard Richards, one of those working on the history, asked whether all of the activities of the Nauvoo City Council should be included—“or only those in which prest. J. Smith was particularly active in getting up.”

Two other questions that arose in the discussion have probably been asked by many practicing Latter-day Saints today who write or publish Mormon history. To generalize: Do we leave out information that could be potentially embarrassing to a Church leader? And, How much information do we include about the activities of the Church’s opponents? Joseph Smith provided the answer that would guide the history writers of that era: “He said if he was writing the history he should put in every thing which was valuable and leave out the rest.” William W. Phelps also remarked in the discussion that Joseph Smith had earlier instructed him to put “every thing that was good” into the history.[32]

Willard Richards’s suggestion that the level of Joseph Smith’s involvement be the determining factor in questions of scope resonates to our own time, as the same factor is used by Joseph Smith Papers Project scholars to decide what to include in the comprehensive edition. The basic question is, Is this a Joseph Smith document (that is, was the record either created by him or received by him and kept in his office)? That question is dispositive, with no consideration of whether the content is “valuable” or “good.” The underlying assumption is that publishing Joseph Smith’s complete documentary record is of inherent value, a point with which William Clayton might have agreed.

Notes

[1] The council was formally organized March 11, 1844. The March 10 meeting can be considered a preliminary meeting of the council.

[2] See Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11 and 14, 1844; February 4, 1845; March 4, 1845, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 42–43, 50, 224–25, 277 (hereafter JSP, CFM); Source Note and Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:5–6, 8–14; George Q. Cannon to Joseph F. Smith, December 8, 1880, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[3] See Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015) (hereafter JSP, J3). This volume contains numerous references to the Nauvoo council minutes. See, for example, JSP, J3:xvi.

[4] See Source Note to Revelation Book 1, in Robin Scott Jensen, Robert J. Woodford, and Steven C. Harper, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 1: Manuscript Revelation Books, vol. 1 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 4–5 (hereafter JSP, R1); Source Note to Joseph Smith, Journal, December 1841–December 1842, in Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Richard Lloyd Anderson, eds., Journals, Volume 2: December 1841–April 1843, vol. 2 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 5 (hereafter JSP, J2); and Source Notes to Joseph Smith, History, Drafts, 1838–circa 1841, in Karen Lynn Davidson, David J. Whittaker, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, eds., Histories, Volume 1: Joseph Smith Histories, 1832–1844, vol. 1 of the Histories series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 187, 192.

[5] “Substitute Words in the 1835 and 1844 Editions of the Doctrine and Covenants,” in Robin Scott Jensen, Richard E. Turley Jr., and Riley M. Lorimer, eds., Revelations and Translations, Volume 2: Published Revelations, vol. 2 of the Revelations and Translations series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2011), 708.

[6] See, for example, Joseph Smith, Journal, March 4, 1843, in JSP, J2:297.

[7] JSP, J3:200–201. Richards first wrote out the correct words, then came back later to cross them out and write them in backward, suggesting he had become worried about confidentiality sometime later. In this same journal passage, Richards also wrote and then later canceled the sentence “Joseph enquired perfect secrecy of them.”

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 14, 1844, in JSP, CFM:50.

[9] Enos 1:13, 16; 3 Nephi 23:7–13; Doctrine and Covenants 21:1.

[10] Record of the Twelve, February 27, 1835, 1–3; Minute Book 1, February 27, 1835, 86–88, both at josephsmithpapers.org.

[11] Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:13–14.

[12] William Clayton, Journal, quoted in JSP, CFM:198n625; Events of June 1844, in JSP, CFM:197–98.

[13] D. Michael Quinn, “The Council of Fifty and Its Members, 1844 to 1945,” BYU Studies 20, no. 2 (1980): 192.

[14] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 10, 1844, in JSP, CFM:39.

[15] Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:7.

[16] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 5, 1844; May 3, 6, and 13, 1844, in JSP, CFM:81–82, 137, 148, 160. One may wonder whether Richards’s minute-taking habits were different enough from Clayton’s that the differences can be seen in the resulting minutes. Since we have only Clayton’s fair copy of the minutes and none of the original raw minutes for these 1844 meetings, the question may be impossible to answer. (Given how difficult Richards’s idiosyncratic handwriting is to transcribe, that any raw council minutes he kept did not survive may have been a boon to the Joseph Smith Papers team!) There is one meeting reported in the record, the one held February 27, 1845, at which neither Clayton nor Richards took the original minutes. Church scribe Thomas Bullock, not a member of the council, attended the meeting and took the minutes. (Editorial Note to Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 27, 1845, in JSP, CFM:247.)

[17] Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:11–14.

[18] A common practice with many of the Church’s records was to create original records on loose paper, then to transfer those into a permanent record book. Revelation Book 1, Revelation Book 2, Minute Book 1, and Minute Book 2 (all available at josephsmithpapers.org) are examples.

[19] Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:9.

[20] Andrew F. Ehat’s 1980 article on the Council of Fifty includes transcripts of William Clayton’s journal entries related to the Nauvoo council. Journal entries for the following dates note that Clayton was “copying” or “recording” the minutes of the council (meaning, copying and expanding the raw minutes into the fair copy): August 18, 1844; September 6, 1844; February 6, 11, 12, 1845; March 6, 7, [unknown day], 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 24, 27, 1845; April 1, 16, 17, 21, 22, 24, 28, 1845; September 11, 1845; October 5, 1845. These entries often note that the copying efforts took “all day.” Andrew F. Ehat, “‘It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth’: Joseph Smith and the Constitution of the Kingdom of God,” BYU Studies 20, no. 3 (1980): 266–73.

[21] JSP, R1:5.

[22] Source Note and Historical Introduction to Minute Book 2, at josephsmithpapers.org.

[23] See Source Notes and Historical Introductions at josephsmithpapers.org for Joseph Smith Letterbook 2; Minute Book 2; and Joseph Smith, History, 1838–56, vol. A-1, respectively.

[24] Joseph Smith, History, 1838–56, vol. C-1, 1260, at josephsmithpapers.org.

[25] See editorial notes on and minutes of these meetings in JSP, CFM:19–50.

[26] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:128.

[27] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 25, 1844, in JSP, CFM:169.

[28] Historical Introduction to Council of Fifty, Minutes, in JSP, CFM:12–13.

[29] William P. Richards to George Miller, February 3, 1845, Brigham Young Office Files, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[30] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:216–18, 232–44; emphasis added.

[31] “Documents Generated, Reviewed, and Received by the Council of Fifty in Nauvoo,” at josephsmithpapers.org.

[32] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 22, 1845, in JSP, CFM:366–69.