Injustices Leading to the Creation of the Council of Fifty

Richard E. Turley Jr.

Richard E. Turley Jr., “Injustices Leading to the Creation of the Council of Fifty,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 5-20.

Richard E. Turley Jr. is the managing director of the Public Affairs Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He was previously an Assistant Church Historian and Recorder and the managing director of the Church History Department.

On the morning of September 25, 1824, Joseph Smith Sr. and some of his neighbors stood, shovels in hand, next to the grave where just ten months earlier, the Smith family had buried the remains of Alvin Smith. The agonizing death of Alvin at the age of twenty-five was still fresh in the minds of Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith and their children. Purposefully, the men at the grave thrust their shovels into the dark soil and began tossing earth to the side, digging deeper and deeper, hoping to hear their tools strike something hard, wooden, and hollow. When at last they found and uncovered the casket, they pried open the lid and peered in. There, much to their relief, they found Alvin’s remains, partially decomposed but undisturbed.

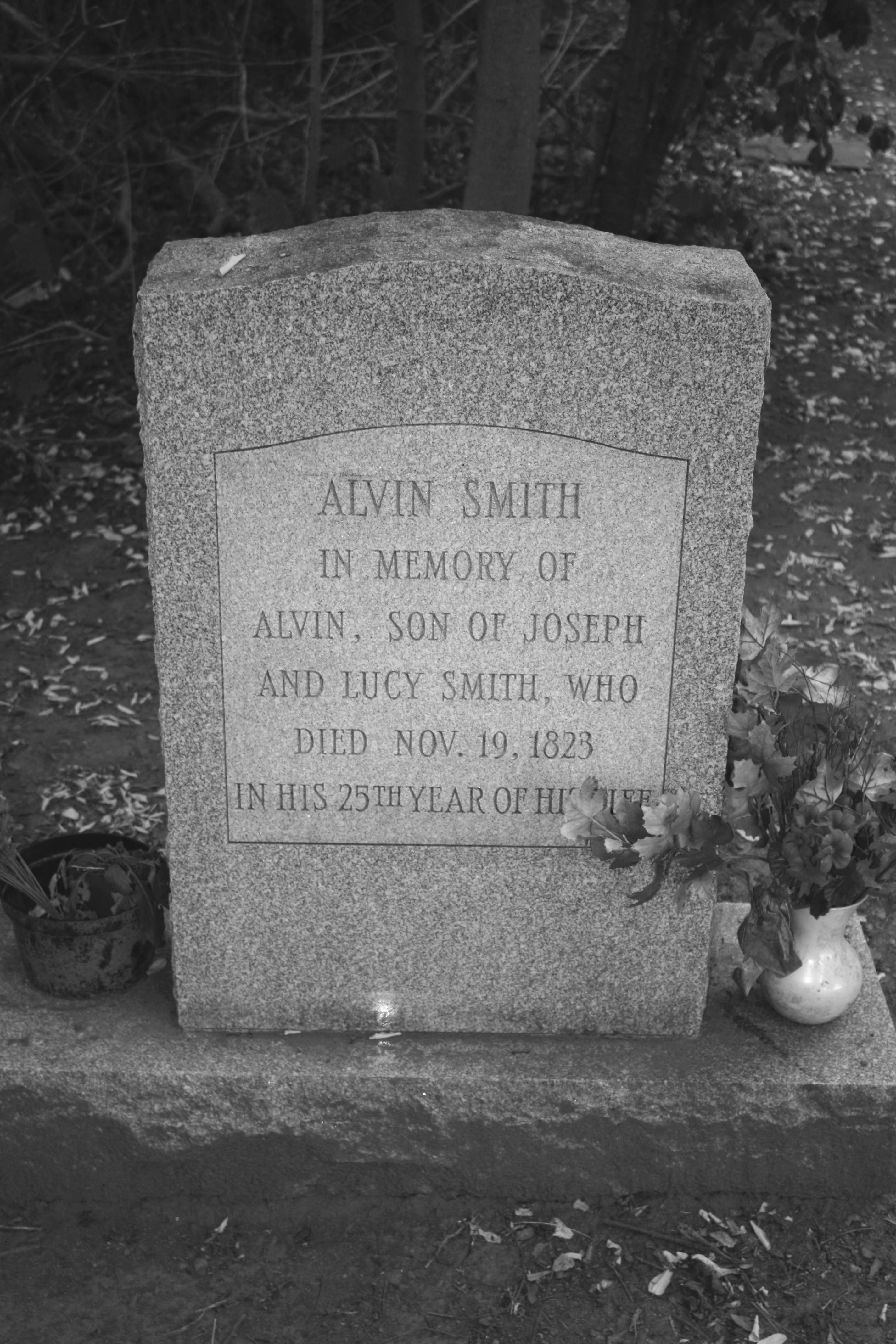

The original gravestone of Alvin Smith, brother of Joseph Smith, is encased on the back side of this newer marker. Photograph by Brent R. Nordgren

The original gravestone of Alvin Smith, brother of Joseph Smith, is encased on the back side of this newer marker. Photograph by Brent R. Nordgren

Later that day, after reinterring his son’s body, Joseph Sr. went to the office of the Wayne Sentinel newspaper and filed a report that was published two days later. Addressed “To the Public,” it countered rumors that Alvin’s remains had been removed and “dissected.” Such rumors had been “peculiarly calculated to harrow up the mind of a parent and deeply wound the feelings of relations.” As such, Joseph Sr. pleaded with those who circulated the rumor to stop.[1]

What could have sparked such an incident? It began four years earlier, when Joseph Smith Jr. reported his First Vision to a trusted religious leader in his area. “I was greatly surprised at his behavior,” Joseph reported. “He treated my communication not only lightly, but with great contempt, saying it was all of the devil.” And it didn’t end there. “I soon found . . . that my telling the story had excited a great deal of prejudice against me,” Joseph wrote, “and was the cause of great persecution.”[2]

In the years that followed, Joseph wrote, “rumor with her thousand tongues was all the time employed in circulating falsehoods about my father’s family, and about myself. If I were to relate a thousandth part of them, it would fill up volumes.”[3] It was one of these rumors that convinced Father Smith to confirm that Alvin’s body had not been stolen.

Throughout Joseph Smith Jr.’s life, persecution followed his religious claims. His search for protection for himself and his followers led to two decisions in the final months of his life: to run for president of the United States and to form the Council of Fifty. In his candidacy for the presidency, he strongly advocated for religious liberty for all Americans, not just for Latter-day Saints. In the Council of Fifty, he discussed the creation of a theocracy outside the borders of the United States that would be defined by its extension of religious liberty to all individuals. This essay contextualizes those decisions in the opposition against the Latter-day Saints, with an emphasis on the 1830s. There were other immediate antecedents for the Council of Fifty and complex causes for its establishment in 1844. Nevertheless, the experiences of Mormons during the 1830s indelibly shaped their mindset on the necessity of religious liberty, the failure of current governments to adequately protect it, and the need for a new type of government to defend the liberty of Latter-day Saints and other religious minorities.

Opposition in Jackson County

While early Mormons had already experienced intense opposition by 1833, their experience that year in Missouri exemplified how far their opponents were willing to go. By that time, thousands of Saints had flocked to Jackson County, Missouri, which one of Joseph Smith’s revelations had designated as the place to build “Zion.” They soon encountered opposition from those who disliked their religious views and also clashed culturally with them. For instance, most of the Saints who moved into Jackson County were northerners, meaning they did not favor slavery, unlike many of their Missouri neighbors.

As opposition to the Saints increased, some Missourians began to vandalize Mormon property and exhibit other signs of prejudice against members of this minority faith. Those with the greatest prejudice began looking for something they could use as a pretense for driving out the members of the Church.

Religious, cultural, economic, and political tensions exploded after the Church’s newspaper in Missouri ran an article advising free blacks coming into the state how to avoid encountering trouble with Missouri’s laws. The article provided the pretense that vigilantes needed to rally support for their cause against the Saints and wreak violence on them.

Resorting to patriotic language, vigilantes drafted a constitution or mob manifesto to draw sympathizers to their cause. As is so often the case with vigilantes, the Missouri mobbers cloaked their extralegal activities in patriotic language. Following the rhetoric of the Declaration of Independence, which concluded with the signers pledging “to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor,” the mobbers concluded their manifesto with similar words: “We agree to use such means as may be sufficient to remove them [the Mormons], and to that end we each pledge to each other our bodily powers, our lives, fortunes and sacred honors.”[4]

After demanding that the Mormons leave immediately and giving them only a short time to respond, the vigilantes attacked the most senior Church leader in the area, Bishop Edward Partridge, kidnapping him from his home, battering him repeatedly, partially stripping off his clothes, and daubing him in tar and feathers.

A group of vigilantes also attacked the Saints’ printing establishment, a sturdy two-story brick structure. They evicted the printer’s family and tore the building completely to the ground, stopping the publication of the first volume of Joseph Smith’s revelations and of the newspaper The Evening and the Morning Star.

In the face of such violence, Church leaders agreed that their people would leave. Later, they reconsidered and decided to seek legal redress for the crimes committed against them and to defend their rights as US citizens.

Irked at the Saints’ legal efforts, the vigilantes intensified the violence. One of the Church members, Lyman Wight, later testified:

Some time towards the last of the summer of 1833, they commenced their operations of mobocracy. . . . [G]angs of from thirty to sixty, visit[ed] the house of George Bebee, calling him out of his house at the hour of midnight, with many guns and pistols pointed at his breast, beating him most inhuman[e]ly with clubs and whips; and the same night or night afterwards, this gang unroofed thirteen houses in what was called the Whitmer Branch of the Church in Jackson county. These scenes of mobocracy continued to exist with unabated fury. Mobs went from house to house, thrusting poles and rails in at the windows and doors of the houses of the Saints, tearing down a number of houses, turning hogs, horses, &c., into cornfields, burning fences, &c.[5]

In October, Wight recounted, the mobbers broke into a Mormon-owned store. When Wight, along with thirty or forty Mormons, went to the scene, he “found a man name of McArty [Richard McCarty], brickbatting the store door with all fury, the silks, calicoes, and other fine goods, entwined about his feet, reaching within the door of the store house.” After McCarty was arrested, he was quickly acquitted. The next day, the Mormons who had testified against McCarty were arrested on charges of false imprisonment and “by the testimony of this one burglar, were found guilty, and committed to jail.”[6]

Used to being treated like a full-fledged citizen before joining the Church, Wight now felt his civil rights were being violated. “This so exasperated my feelings,” he said, “that I went with two hundred men to enquire into the affair, when I was promptly met by the colonel of the militia, who stated to me that the whole had been a religious farce, and had grown out of a prejudice they had imbibed against said Joseph Smith, a man with whom they were not acquainted.”[7]

Hoping to de-escalate the violence, Wight agreed that the Saints would give up their arms if the militia colonel would take the arms from the mob. To this the colonel cheerfully agreed, and pledged his honor with that of Lieutenant Governor [Lilburn W.] Boggs . . . and others. This treaty entered into, we returned home, resting assured on their honor, that we would not be farther molested. But this solemn contract was violated in every sense of the word. The arms of the mob were never taken away, and the majority of the militia, to my certain knowledge, was engaged the next day with the mob, ([the colonel and] Boggs not excepted,) going from house to house in gangs of sixty to seventy in number, threatening the lives of [Mormon] women and children, if they did not leave forthwith.[8]

Church member Barnet Cole later signed an affidavit explaining what happened to him. According to his affidavit, three armed men accosted him at his house and compelled him to “go out a pace with them,” telling him “some gentleman wished to see him.” He was forced to a spot “where there were from forty to fifty men armed.”

One of the armed men asked his kidnappers, “Is this mister Cole?”

“Yes,” one replied.

Challenging Barnet’s religious views, an armed man asked him, “Do you believe in the book of Mormon?”

“Yes,” he replied.

Swearing, the leader said, “That is enough. Give it to him.”

The mob stripped off some of his clothes, “laid on ten lashes” as a warning, and then told him he could go home. Barnet did not leave the area, and some five weeks later, a mob came “into his house and gave him a second Whiping and ordered him to leave the County or it would be worse for him.” He then left for Clay County.[9]

With all the Jackson County violence in late 1833, men, women, and children were chased from their homes, and they scrambled for their lives. Lyman Wight testified: “I saw one hundred and ninety women and children driven thirty miles across the prairie, with three decrepit men only in their company, in the month of Nov., the ground thinly crusted with sleet, and I could easily follow their trail by the blood that flowed from their lacerated feet!! on the stubble of the burnt prairie.” He also described how the mob burned down all the Mormon homes in Jackson County.[10]

Despite the continual threat of violence, some Mormons returned to Jackson County. Lyman and Abigail Leonard returned to avoid starving to death. Abigail recalled, “A company of men armed with whips and guns about fifty or sixty came to the house. . . . Five of the numbered entered. . . . They ordered my husband to leave the house threatning to shoot him if he did not, he not complying with their desires, one of the five took a chair, and struck him upon the head, knocking him down, and then dragging him out of the house. I in the mean time beging of them to spare his li[f]e.”

Abigail tried to save her husband, but three of the men aimed guns at her and swore to shoot her if she resisted further. “While this was transpiring,” she said, one of the men “jumped upon my husband with his heels, my husband then got up they striping his clothes all from him excepting his pantaloons, then five or six attacked him with whips and gun sticks, and whipped him until he could not stand but fell to the ground.”[11] They “beat and whipt” him “until [his] life,” she said, “was almost extinct.”[12]

Appeals for Protection and Redress

One of the challenges the Saints faced during this time period was that their appeals for protection from the government went unheeded, in part because the officials who should have protected them either participated in the mobbings themselves or were sympathetic to those who did. The Saints then sought redress in the courts, only to face similar frustrations.

For example, when Edward Partridge initiated legal proceedings against those who tarred and feathered him, the leaders of the mob could not deny what they had done, since there were so many witnesses to the highly public event. Instead, despite kidnapping, assaulting, and battering the bishop, with no legal provocation on his part, the attackers claimed that they did it in self-defense.

The defense was so ludicrous that even the judge, a mob sympathizer, could not in good conscience accept the attackers’ self-defense claim. So he did the next best thing for the mobbers. He ruled in favor of Partridge but awarded him only a penny and a peppercorn.[13]

No wonder the Saints grew frustrated. They were following the rules that were supposed to protect citizens, but because of their status as members of a despised minority faith, the law did not protect them from violence or provide redress after it occurred.

Temporary Refuge in Clay County

The Saints who were driven out of Jackson County sought refuge in Clay County, which was north across the Missouri River. There they found a measure of sympathy among some of the citizens.[14] Meanwhile, Lyman Wight rode long distances trying to find others who would sympathize with his fellow Saints and come to their aid. He later testified:

I left my family for the express purpose of making an appeal to the American people to know something of the toleration of such vile and inhuman conduct, and travelled one thousand and three hundred miles through the interior of the United States, and was frequently answered “That such conduct was not justifiable in a republican government; yet we feel to say that we fear that Joe Smith is a very bad man, and circumstances alter cases. We would not wish to prejudge a man, but in some circumstances, the voice of the people ought to rule.”[15]

Such replies reflected a problem in the United States at the time. The ruling majority could often do more or less as it pleased, even if that meant violating the civil rights of minorities. The minorities were expected to bend before the collective prejudice of the majority and could do little to protect themselves or obtain justice in the courts.

The agitators in Jackson County began making so much noise against the Mormons in Clay County that it affected the Saints’ sympathizers there, who wanted to avoid trouble for themselves and their communities.[16] In addition, the impoverished refugees from Jackson County had begun working for the Clay County citizens, and as the Saints began to prosper economically and were joined by fellow Saints from elsewhere, they began to have, by virtue of their numbers, political power as well. This incited jealousies. Lyman Wight recalled that “when the Saints commenced purchasing some small possessions for themselves; this together with the emigration created a jealousy on the part of the old citizens that we were to be their servants no longer.” Wight went on to describe gruesome whippings and beatings that were visited on the Saints.[17]

Once again, those who inflicted this violence on the Saints justified their crimes under the guise of patriotism. One mobber, who seemed to consider himself an upstanding citizen, wrote to family members about the violence he helped inflict. “We are trampling on our law and Constitution,” he admitted in his letter, “but we Cant Help it in no way while we possessed the Spirit of 76,” he claimed. “Six of our party . . . went to a mormon town. Several mormons Cocked their guns & Swore they would Shoot them. After Some Scrimiging two white men took a mormon out of Company & give him 100 lashes & it is thought he will Die of this Beating.”[18] The almost matter-of-fact way that the mobber includes this description in a family letter is chilling.

To avoid further trouble, the Saints left Clay County and settled in Caldwell County, a new county established by sympathetic Missouri state legislators as a “sort of Mormon reservation.”[19] At first, this seemed to settle the violence, but not for long.

The Mormon War and the Extermination Order

Latter-day Saint men who went to vote at Gallatin, Missouri, faced opposition and fought back, winning the election-day fight but giving their critics just what they wanted—a reason to label them dangerous and to call for driving them out once again. What followed has been called the 1838 “Mormon War,” a series of skirmishes (some deadly) between Missouri vigilantes and militiamen on one side and Latter-day Saints on the other.

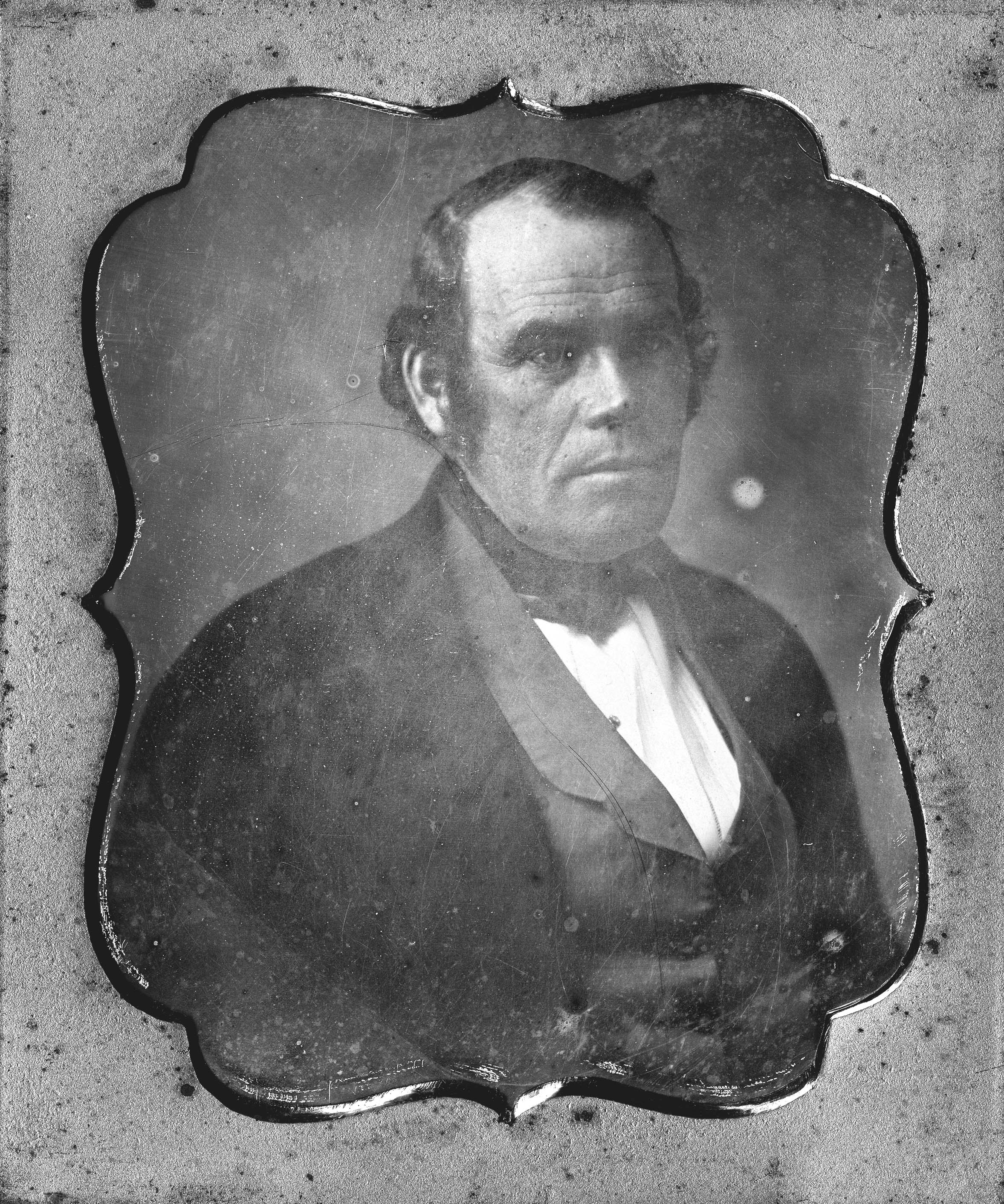

Parley P. Pratt was one of several members of the Church who wrote important accounts of the persecutions experienced by Church members in Missouri. Photograph, circa 1850-56, likely by Marsena Cannon or Lewis W. Chaffin. Courtesy of History Library, Salt Lake City.

Parley P. Pratt was one of several members of the Church who wrote important accounts of the persecutions experienced by Church members in Missouri. Photograph, circa 1850-56, likely by Marsena Cannon or Lewis W. Chaffin. Courtesy of History Library, Salt Lake City.

In De Witt, Carroll County, vigilantes demanded that the Mormons leave and organized a “safety committee,” appealing to other counties for “aid to remove Mormons, abolitionists, and other disorderly persons.”[20] A Missouri newspaper reported these actions and, though sympathetic to the vigilantes, commented, “By what color of propriety a portion of the people of the State, can organize themselves into a body, independent of the civil power, and contravene the general laws of the land by preventing the free enjoyment of the right of citizenship to another portion of the people, we are at a loss to comprehend.”[21]

The De Witt Mormons appealed to Governor Lilburn W. Boggs and a Missouri militia general to save them from extermination. The general brought his men and ordered the mob to disperse. The vigilantes refused, however, and the general’s men threatened to join the mob. The general had to withdraw his troops and wrote to his superior officer, asking the governor to intervene.

Governor Boggs, who had participated in the expulsion of the Saints from Jackson County and valued his political position, ignored his duty to protect the Saints, saying that the “quarrel was between the Mormons and the mob.”[22] Abandoning all hope of government protection, some four hundred Saints of De Witt, who had suffered intense hunger during the siege, fled the area, leaving behind valuable property that fell into the hands of their persecutors. During their flight to safety, some died.[23]

Other Saints in northwestern Missouri also suffered. In 1838, Asahel Lathrop purchased a land claim and settled down, “supposing,” as he said, “that I was at peace with all men.” On August 6, however, he joined other Mormon men in defending their right to vote at Gallatin. Before long, other men threatened to kill him if he did not leave the area. Some of his family members were sick at the time and could not easily be moved. His wife pleaded for him to leave the children with her and flee for his life. He hesitated but finally gave in to her pleadings.

Not long after he left, a mob of fourteen or fifteen men occupied his home and, as he later testified, “abus[ed] my family in almost every form that Creturs in the shape of human Beeings could invent.” One of his children soon died. After appealing to local authorities for protection, he returned home to find the other members of his family “in a soriful situation not one of the remaining ones able to wait uppon the other.” He moved them sixty miles away, but his wife and two other family members soon died due to the “trouble and the want of care which they were deprived of by a Ruthless Mob.”[24]

Left on their own, the Saints did their best to defend themselves and went on the offensive, making preemptive strikes to eliminate threats, disarm the enemy, and resupply their own people. A group of Missouri militia began driving Latter-day Saint families from their homes and took three prisoners. Several Mormons mobilized to rescue them before their rumored execution and ended up in a firefight that became known as the Battle of Crooked River. Although Mormon casualties exceeded those of the Missourians, exaggerated rumors reached Governor Boggs and led him to issue an order to exterminate or drive the Mormons from the state.[25]

A short time later, a large group of armed Missourians attacked the village of Hawn’s Mill, which was occupied primarily by Latter-day Saints. Ignoring cries for mercy, the attackers killed seventeen men and boys and wounded many others. Before blowing off the head of a young boy found hiding under the bellows in the blacksmith shop, one vigilante uttered the slogan used for generations by bigots to justify the killing of the children of minorities: “Nits will make lice.” The killers then plundered the village.[26]

Flight to Illinois

With the upswell in violence, Saints in outlying areas fled to the Mormon capital of Far West for protection. There they waited, hoping that the government would intervene and rescue them. Instead, they were surrounded by troops, their leaders captured, and the people forced to sign over their property to pay the costs of the war. They were ordered to leave the state or face further violence. Over the course of the fall and winter, thousands of Saints braved harsh conditions to flee east across the prairie and over the Mississippi River. Meanwhile, Joseph Smith and his fellow prisoners listened to guards taunting them with stories of abuse heaped on Mormon victims.[27]

Writing from the Liberty jail, Joseph Smith and his fellow prisoners wrote of what they called “a lamentable tail[,] yea a sorrifull tail too much to tell[,] too much for contemplation[,] too much to think of for a moment[,] too much for human beings.” Recounting some of the war’s atrocities, they wrote of a Mormon man who was “mangled for sport” and of Latter-day Saint women who were robbed “of all that they have their last morsel for subsistance and then . . . violated to gratify the hellish desires of the mob and finally left to perish with their helpless of[f]spring clinging around their necks.”[28]

Joseph, his brother Hyrum, and their companions later escaped to Illinois, where they joined many of the other refugee Saints, though Joseph never felt entirely safe there, as Missouri officials tried time and again to recapture and bring him back to what likely would have been execution.

The Saints tried to obtain justice for those who were killed and wounded, as well as compensation for the thousands whose property was taken from them. But all to no avail. Joseph even went to Washington, where he spoke with President Martin Van Buren. The president was sympathetic but thought the federal government had no power in the matter. Besides, he said, if he were to help the Mormons, he would lose the vote of the state of Missouri. In effect, he said, “Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you.”[29]

Based on these experiences, the Saints figured that if they were to have fairness and justice, they needed to have their own government, their own courts, and their own state-sanctioned militia. In the new settlement they established in Illinois, named Nauvoo, Mormons were the majority, and Joseph Smith became leader of the city, the court, and the militia. The city grew and prospered, aided by an influx of immigrant converts, and Joseph continued to seek equality and justice for his people. In late 1843, Joseph wrote the leading US presidential candidates, inquiring what they would do to protect the rights of Latter-day Saints. After getting unsatisfactory answers, he decided in early 1844 to run for president, with Sidney Rigdon as vice presidential candidate. Joseph’s presidential campaign would be a way to draw attention to the plight of Saints, slaves, prisoners, debtors, and other downtrodden peoples. These events, as well as others in the early Nauvoo years, also provided crucial context for the establishment of the Council of Fifty in March 1844. A few months later, a mob killed Joseph and his brother Hyrum.

A Few Closing Observations

First, although Latter-day Saints sometimes fought back and at times even went on the offensive, they were overwhelmingly the victims of illegal and extralegal violence. Second, the three branches of government failed to protect the Saints before they became victims or to compensate them for their losses afterward. Third, as is so often the case with groups who have minority status, the Mormons were victims of structural bias. In general, when they did wrong, they were punished harshly. But when others wronged them, even severely, they were not punished at all.

This history of repeated injustices suffered by the Latter-day Saints provides essential background to understanding the establishment of the Council of Fifty—a body that was designed, as Joseph Smith put it, “to be got up for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”[30]

Notes

[1] “To the Public,” Wayne Sentinel (Palmyra, NY), October 27, 1824.

[2] Joseph Smith—History 1:21–23, 27.

[3] Joseph Smith—History 1:61.

[4] “To His Excellency, Daniel Dunklin, Governor of the State of Missouri,” Evening and Morning Star 2, no. 15 (December 1833): 228.

[5] Lyman Wight, Testimony, Times and Seasons 4, no. 17 (1843): 262.

[6] Wight, Testimony, 262.

[7] Wight, Testimony, 262.

[8] Wight, Testimony, 262.

[9] Barnet Cole, Affidavit of January 7, 1840, in Mormon Redress Petitions: Documents of the 1833–1838 Missouri Conflict, vol. 16 of the Religious Studies Center Monograph Series, ed. Clark V. Johnson (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 1992): 431–32.

[10] Wight, Testimony, 263.

[11] Abigail Leonard, Affidavit of March 11, 1840, in Mormon Redress Petitions, 273–74.

[12] See unsworn, undated petition of Lyman Leonard in Mormon Redress Petitions, 699.

[13] Karen Lynn Davidson, Richard L. Jensen, and David J. Whittaker, eds., Histories, Volume 2: Assigned Histories, 1831–1847, vol. 2 of the Histories series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2012), 209, 227 (hereafter JSP, H2).

[14] Parley P. Pratt et al., “‘The Mormons’ So Called,” The Evening and the Morning Star, Extra, February 1834, [2].

[15] Wight, Testimony, 263.

[16] Edward Partridge, “A History, of the Persecution, of the Church of Jesus Christ, of Latter Day Saints in Missouri,” Times and Seasons 1, no. 4 (1840): 50, in JSP, H2:226.

[17] Wight, Testimony, 263.

[18] Durward T. Stokes, ed., “The Wilson Letters, 1835–1849,” Missouri Historical Review 60, no. 4 (July 1966): 508–9. On the writer’s distinction between “white men” and “a mormon,” see W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[19] Chicago Times, August 7, 1875, https://

[20] “Anti-Mormons,” Missouri Republican (St. Louis), August 1838, in Publications of the Nebraska State Historical Society: Volume XX, ed. Albert Watkins (Lincoln: Nebraska State Historical Society, 1922), 80.

[21] “The Mormons,” Southern Advocate (Jackson, MO), September 1, 1838, https://

[22] “Extract, from the Private Journal of Joseph Smith Jr.,” in Times and Seasons 1, no. 1 (1839): 2–9, josephsmithpapers.org/

[23] “Trial of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 4, no. 17 (1843): 257; Joseph Smith, History, 1838–1856, vol. B-1, 836, josephsmithpapers.org/

[24] Asahel A. Lathrop, Affidavit of May 8, 1839, and March 17, 1840, in Mormon Redress Petitions, 263–66.

[25] Lilburn W. Boggs to John B. Clark, October 27, 1838, Mormon War Papers, Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City.

[26] History of Caldwell and Livingston Counties, Missouri: Written and Compiled from the Most Authentic Official and Private Sources, including a History of Their Townships, Towns and Villages (St. Louis: National Historical, 1886), 149.

[27] “Memorial to the Missouri Legislature,” January 24, 1839, Joseph Smith Letterbook 2, 66–67, josephsmithpapers.org/

[28] Joseph Smith to the Church and Edward Partridge, March 20, 1839, 3, josephsmithpapers.org/

[29] Joseph Smith to Hyrum Smith and High Council, December 5, 1839, Joseph Smith Letterbook 2, 85, josephsmithpapers.org/

[30] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 128.