God and the People Reconsidered

Further Reflections on Theodemocracy in Early Mormonism

Patrick Q. Mason

Patrick Q. Mason, “God and the People Reconsidered: Further Reflections on Theodemocracy in Early Mormonism,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 31-42.

Patrick Q. Mason is Howard W. Hunter Chair of Mormon Studies and dean of the School of Arts and Humanities at Claremont Graduate University and a nationally recognized authority on Mormonism. His publications include The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormonism in the Postbellum South (2011), Planted: Belief and Belonging in an Age of Doubt (2015), and What Is Mormonism? A Student's Introduction (2017).

Joseph Smith’s quixotic 1844 presidential campaign, which ended prematurely and tragically with his murder in June of that year, introduced into the Mormon and American lexicon the concept of “theodemocracy.” In a ghostwritten article in the Latter-day Saint newspaper Times and Seasons outlining his political principles, Smith declared, “As the ‘world is governed too much’ and as there is not a nation of dynasty, now occupying the earth, which acknowledges Almighty God as their law giver, and as ‘crowns won by blood, by blood must be maintained,’ I go emphatically, virtuously, and humanely, for a Theodemocracy, where God and the people hold the power to conduct the affairs of men in righteousness.” Smith went on to say that such a “theodemocratic” arrangement would guarantee liberty, free trade, the protection of life and property, and indeed “unadulterated freedom” for all.[1]

I can’t recall when I first encountered Smith’s notion of theodemocracy, but I became particularly interested in the subject when, as a master’s student in international peace studies at the University of Notre Dame, I took a course on democratic theory. A search of electronic databases containing early American imprints, newspapers, and other primary sources suggested that the word “theodemocracy” was not in wide circulation at the time, and perhaps that the concept was original to Smith (or his ghostwriter William W. Phelps). I wondered if theodemocracy might even constitute a uniquely Mormon contribution to political theory. What began as a course paper eventually culminated in my article “God and the People: Theodemocracy in Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” published in 2011 in the Journal of Church and State.[2] My research suggests that outside of Mormon circles the term has rarely if ever been invoked, with the prominent exception of the influential twentieth-century Pakistani Islamist author and political organizer Sayyid Abul A‘la Maududi.[3]

“God and the People” was not intended to provide a comprehensive history of Mormon political thought—an ambitious project that has yet to be undertaken.[4] Nevertheless, within its rather narrowly tailored perspective, the article did attempt to contribute to important conversations in Mormon history, American political history, and democratic theory. I argued that the Mormon concept of theodemocracy was designed to mediate in a contemporaneous debate over how to best protect minority rights and religious liberty—subjects that were far from academic for the earliest generations of Latter-day Saints. That Mormons would even consider a notion such as theodemocracy suggests their complicated relationship with American political ideals, even at a time when those ideals were themselves complex and in flux. Latter-day Saints joined other Americans in reflecting on the meaning of freedom and how to guarantee its blessings for all, not only the majority. From their own experience and reading of the US Constitution, Mormons identified religious freedom as the first and most important freedom, and they sought a political theory and system that would prevent the abuses they had recently suffered in Missouri.

The irony is that the Latter-day Saints’ proposed remedy was viewed by their opponents as equally if not more dangerous than the sociopolitical ills it sought to cure. As I wrote, “Each side accused the other of undermining democracy and basic liberties: Smith and the Mormons embraced a more robust application of revealed religion in the public sphere as the answer to the secular government’s hostility to religious minorities’ rights (namely their own), while anti-Mormon critics denounced the prophet as a tyrant and his politics as theocratic despotism.”[5] Theodemocracy, then, provides an excellent window onto the antiliberal tradition in American politics. The illiberalism of vigilantism and state-sponsored violence against a particular religious minority group was countered by the illiberalism of theodemocracy. A consideration of Mormon theodemocracy therefore fixes our gaze upon the contending illiberalisms of nineteenth-century American political thought and behavior.

I concluded my article by expressing skepticism about theodemocracy as a tenable political theory, arguing that theos would always trump demos, and that such a system would perpetually struggle with an inability to tolerate real dissent. The particular turns of Mormon history following Joseph Smith’s death, and especially after Wilford Woodruff’s 1890 Manifesto, meant that what began as a radical political idea informed by millenarian theology became domesticated and limited to applications within ecclesiastical government. In the twentieth century, theodemocracy became far less political, far more churchly, and thus far less dangerous.

The Alienation of Church Leaders

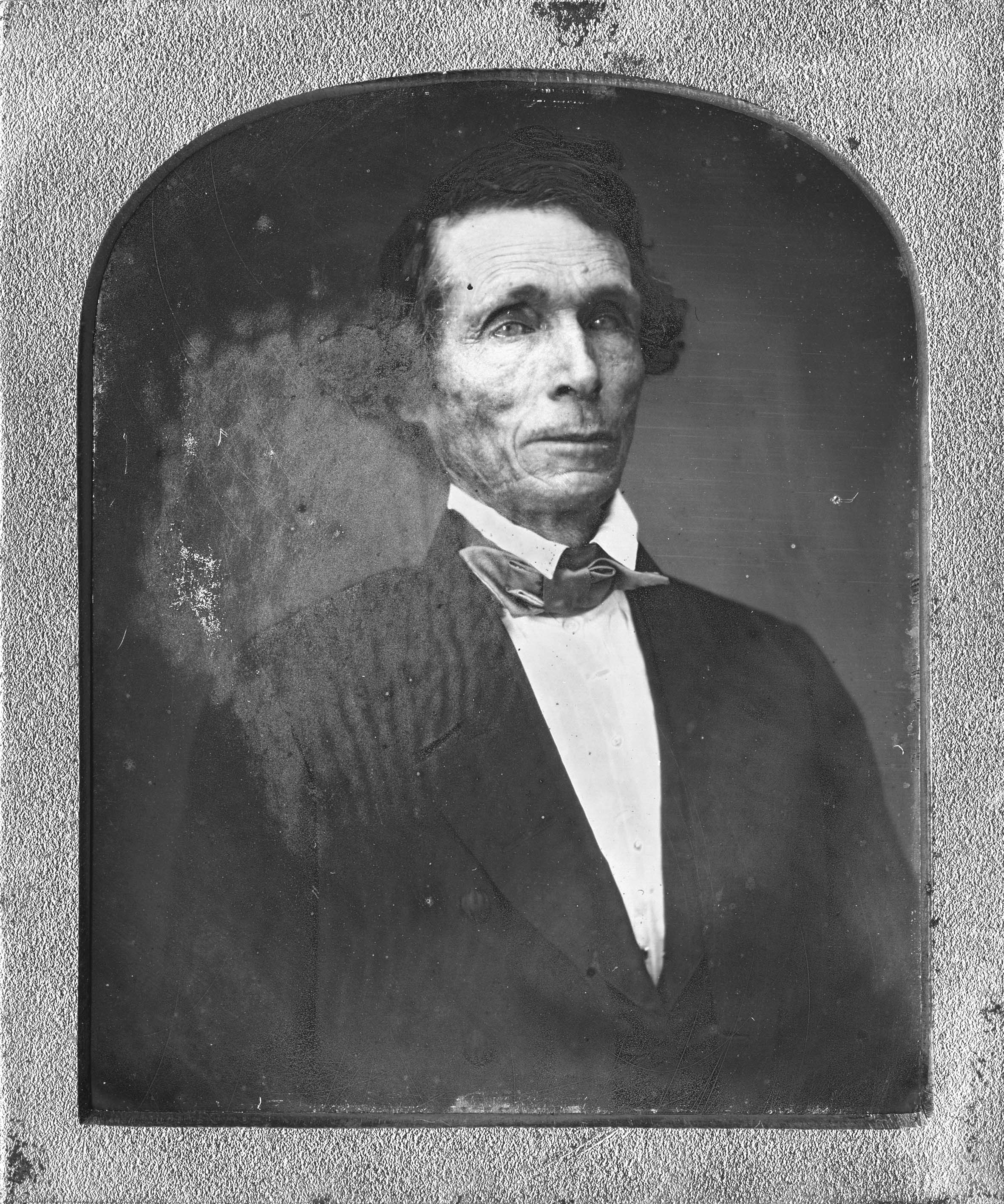

William W. Phelps and other council members expressed bitter feelings towards the US government. Photograph, circa 1850-60, likely by Marsena Cannon. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

William W. Phelps and other council members expressed bitter feelings towards the US government. Photograph, circa 1850-60, likely by Marsena Cannon. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The recent publication of the Council of Fifty’s minutes from the final months of Joseph Smith’s life provides an opportunity to reappraise the arguments I made in my 2011 article.[6] A thorough review of the Joseph Smith–era minutes does not upend any of my claims, but they do provide further texture and depth to our understanding of early Mormon politics, history, and theology. In particular, the minutes reveal a core of Latter-day Saint leaders even more alienated from American society than I suggested in my article. It still holds true, as I argued, that “the ranks of Mormonism in its first decade were hardly filled with fanatic dissidents, revolutionaries, or theocrats.”[7] But the Council of Fifty minutes make clear that by 1844, many of the leading men of Mormonism had adopted a more jaded view. John Taylor dimly reviewed “the positions and prospects of the different nations of the earth” (though his mental geography seemed limited to the United States and northern Europe) and later asserted that “this nation is as far fallen and degenerate as any nation under heaven.”[8] William W. Phelps begrudgingly admitted there were “a few pearls” in the Declaration of Independence and US Constitution—which an 1833 revelation said was “established . . . by the hands of wise men whom I [God] have raised up unto this very purpose”—but also “a tremendous sight of chaff.” Whatever original inspiration there may have been in the nation’s founding, Phelps said, “the boasted freedom of these U. States is gone, gone to hell.”[9] Sidney Rigdon embraced the world’s degenerate political condition as a harbinger of the apocalypse. “The nations of the earth are very fast approximating to an utter ruin and overthrow,” he proclaimed. “All the efforts the nations are making will only tend to hasten on the final doom of the world and bring it to its final issue.”[10] In recent years many scholars have emphasized the optimistic, progressive nature of early Mormon theology. Without discounting that positive strain of thought within the movement, the Council of Fifty minutes remind us that many early Mormons shared a rather dark view of the world that lay beyond gathered Zion, a pessimism founded upon Smith’s millenarian revelations and fueled by the Missouri persecutions.[11]

The council members’ alienation with present governments led to their openness to, and even enthusiasm for, a theocratic alternative. By focusing so intently on theodemocracy, my article underplayed the commitments of many early Mormon leaders to plain old theocracy. In the Council of Fifty’s first meeting on March 11, 1844, clerk William Clayton recorded that “all seemed agreed to look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy.”[12] Indeed, theocracy was built into the council’s DNA from the beginning. Sidney Rigdon, Brigham Young, and other council members stood ready to ditch demos in favor of theos and the political rule of God’s appointed servant, Joseph Smith. Rigdon asserted that the council’s “design was to form a Theocracy according to the will of Heaven.”[13] Brigham Young declared, “No line can be drawn between the church and other governments, of the spritual and temporal affairs of the church. Revelations must govern. The voice of God, shall be the voice of the people.”[14] Later, Young argued that the government of the kingdom of God was in no need of a constitution so long as its subjects had Smith as their “Prophet, Priest and King,” who represented “a perfect committee of himself” through whom God would speak.[15] One can see here the foundations of an authoritarian streak that has manifest itself throughout the larger Mormon tradition, whether it be in what historians have characterized as Young’s “kingdom in the West” or the “one-man rule” that Rulon Jeffs introduced in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the 1980s.[16]

Not all council members were so enthusiastic about theocracy. Almon Babbitt departed from his fellow council members to explain (and presumably defend) “laws in general” and especially “the laws of the land.” He went so far as to remind his colleagues of “the apostacy of the children of Israel in choosing a king.”[17] Babbitt’s reservations notwithstanding, one can sense in the minutes an emergent groupthink as council members built upon one another’s exuberance for the establishment of the political kingdom of God, confirming and even outperforming one another’s earnest declarations.

At the same time, the minutes affirm that for all their theocratic illiberality, the council members were unanimously committed, at least in their own minds, to equal rights for all. They believed that “having sought in vain among all the nations of the earth, to find a government instituted by heaven; an assylum for the opprest; a protector of the innocent, and a shield for the defenceless,” it was their God-given duty to create a government that would not only fulfill prophecy but also protect society’s most vulnerable members.[18] At times their commentary was concerned primarily with self-protection and the maintenance of their own rights, but this special pleading did frequently give way to more universalistic sentiments. Religious freedom provided the foundation for their broader thinking about individual liberties and the limits of government power. For instance, Amasa Lyman opined that one of their chief purposes in establishing the government of the kingdom of God was to “secure the right of liberty in matters of conscience to men of every character, creed and condition in life. . . . If a man wanted to make an idol and worship it without meddling with his neighbor he should be protected. So that a man should be protected in his rights whether he choose to make a profession of religion or not.”[19] The kingdom of God would protect the rights of conscience for Mormons, idolaters, and atheists alike.

Joseph Smith’s Views on Theodemocracy

Amidst the swirl of theocratic enthusiasm, Joseph Smith emerges in the minutes as perhaps the most moderate member of the council. To be sure, he did allow his colleagues to proclaim him as their prophet, priest, and king.[20] And he was the one who gave Brigham Young the idea that, as chairman of the council, Smith was “a committee of myself.”[21] Nevertheless, in the council’s discussions of theocracy, Smith left far more room for human agency and coparticipation than did many of his peers. While the word theodemocracy is never explicitly used in the minutes by Smith or any other council member, in his remarks on April 11, just four days before publishing the newspaper article that did introduce the term, Smith articulated a vision of God and the people working together to govern human affairs in righteousness. He declared that theocracy meant “exercising all the intelligence of the council, and bringing forth all the light which dwells in the breast of every man, and then let God approve of the document.” Smith said it was not only advisable but in fact necessary for the government of the kingdom of God to operate in this fashion so as to prove to the council members that “they are as wise as God himself.” A week earlier, Brigham Young had asserted, “The voice of God, shall be the voice of the people,” but now Smith reversed that formulation by declaring, “Vox populi, Vox Dei.” The people would still assent to the will of God, but in Smith’s formulation the process would be far more collaborative than what his colleagues had imagined.[22]

Smith’s statements, carving out space for human coparticipation with God, make even more sense when we recognize that they were expressed a mere four days after he delivered his seminal sermon known as the King Follett discourse. In that remarkable address he proclaimed, “God Himself who sits enthroned in yonder heavens is a Man like unto one of yourselves,” and further, that the core essence, or intelligence, of each human is “as immortal as, and is coequal with, God Himself.”[23] This radical collapse of ontological distance between God and humanity allowed for Smith to believe that humans could confidently speak for and in the name of God—just as he had been doing for nearly two decades. As I concluded in my original article, Joseph Smith’s principal impulse was “to bring God and humanity together in radically new ways. . . . Politically, this meant devising a system in which God and the people would work jointly in administering the government of human affairs. The notion of theodemocracy thus represented the logical culmination of Mormon ideas about the social-political relationships that people had with one another and with the divine.”[24]

Joseph Smith tempered the more theocratic leanings of his fellow council members not only by introducing demos into the equation but also in affirming that the kingdom of God and the church of Jesus Christ were two separate institutions, each with its own laws and jurisdiction. In determining this he was settling a debate that occupied most of the meeting on April 18. “The church is a spiritual matter,” he clarified, whereas “the kingdom of God has nothing to do with giving commandments to damn a man spiritually.”[25]

Diversity and Dissent

Even with this relatively firm understanding of the separation of church and state, Smith and the council never fully grappled with the problem of genuine diversity and dissent. The nature of the council’s governance, requiring that all decisions be made with full unanimity, can be interpreted in at least two ways: first, as a pragmatic response to democratic politics intended as a guard against the tyranny of the majority; or second, implying a naive belief that all people of goodwill, especially when guided by the Holy Spirit, would come to the same conclusions on any matter of import. These two interpretations are not mutually exclusive, and both seem plausible when understood against the backdrop of antebellum American politics and culture. Indeed, the second interpretation, with its faith in the very possibility of political and religious consensus, would be consistent with the philosophy regnant in late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century America which produced “an almost reverential respect for the certainty of knowledge achieved by careful and objective observation of the facts known to common sense.”[26] At the time of the Restoration, this “Common Sense philosophy seemed to have swept everything before it in American intellectual life,” and virtually “all were convinced that in fair controversy universal truth would eventually flourish.”[27] In other words, early nineteenth-century Americans—including Mormons—generally believed that any two or more rational people looking objectively at the same set of facts would come to similar conclusions. Joseph Smith could therefore propose an extreme libertarian view of government, suggesting that “it only requires two or three sentences in a constitution to govern the world,” precisely because he believed that equipped with freedom, proper teaching, and correct information, humans could and would act in complete harmony for the common good.[28] The inclusion of three non-Mormons on the council was therefore a gesture not just of tokenism or religious liberality but also an expression of a sincere belief that spiritual difference would not impede social harmony and political unity.

Such sincerity would prove insufficient in the face of real difference and especially dissent. Smith and the other council members, many of whom also served as municipal officials in Nauvoo, were unable to tolerate even a rival newspaper, to say nothing of how their proposed system would respond to the deep pluralism characteristic of modern life in the twenty-first century. All of the council’s fine talk of freedom, liberty, and minority rights proved ephemeral when the authority of their prophet, priest, and king was publicly challenged. Whether properly understood as theocracy or theodemocracy, the government of the kingdom of God proved to be incompatible with a pluralistic society and therefore untenable as a modern political theory.[29]

Conclusion

The Council of Fifty stands as a fascinating study of the illiberal tradition in American politics and society. Though fueled in substantial part by Smith’s millenarian revelations, the theocratic strain in Mormonism must be understood principally as the reaction of a people otherwise inclined toward patriotism and republicanism but deeply scarred by the failure of the American nation to live up to its own highest ideals. Early Mormon theo(demo)cracy can therefore be considered alongside other protest movements born of profound alienation from the American state—such as the American Indian Movement and various black nationalist groups, including the Nation of Islam and Black Panthers. These groups’ failure to provide satisfactory alternatives should not diminish our recognition of the potency of their complaints and the depth of their disaffection. In this manner, it is precisely those minority groups who flirt with nondemocratic polities who underscore the nation’s perpetual struggle to guarantee, in Joseph Smith’s words, “those grand and sublime principles of equal rights and universal freedom to all.”[30]

Notes

[1] Joseph Smith, “The Globe,” Times and Seasons 5, no. 8 (April 15, 1844): 510. The article was ghostwritten by William W. Phelps.

[2] Patrick Q. Mason, “God and the People: Theodemocracy in Nineteenth-Century Mormonism,” Journal of Church and State 53, no. 3 (Summer 2011): 349–75.

[3] In his influential 1955 treatise The Islamic Law and Constitution, Maududi wrote, “If I were permitted to coin a new term, I would describe this system of government as a ‘theo-democracy,’ that is to say a divine democratic government, because under it the Muslims have been given a limited popular sovereignty under the suzerainty of God.” Sayyid Abul A’la Maududi, The Islamic Law and Constitution, trans. and ed. Khurshid Ahmad, 7th ed. (Lahore, Pakistan: Islamic Publications, 1980), 139–40. On the broader context for Maududi’s concept of theodemocracy, see Mumtaz Ahmad, “Islamic Fundamentalism in South Asia: The Jamaat-i-Islami and the Tablighi Jamaat of South Asia,” in Fundamentalisms Observed, ed. Martin E. Marty and Scott Appleby, vol. 1 of The Fundamentalism Project (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 457–530.

[4] An important step in this direction, though still limited to the earliest years of the Mormon movement, is Mark Ashurst-McGee, “Zion Rising: Joseph Smith’s Early Social and Political Thought” (PhD diss., Arizona State University, 2008).

[5] Mason, “God and the People,” 358.

[6] Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016) (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[7] Mason, “God and the People,” 354.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 19 and April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:52, 114.

[9] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:94; Doctrine and Covenants 101:80.

[10] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:104.

[11] On Mormonism’s optimistic theology, see Terryl Givens and Fiona Givens, The God Who Weeps: How Mormonism Makes Sense of Life (Salt Lake City: Ensign Peak, 2012). On early Mormon millenarianism, see Grant Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993).

[12] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:40.

[13] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:88.

[14] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 5, 1844, in JSP, CFM:82.

[15] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:120.

[16] See John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012); Marianne T. Watson, “The 1948 Secret Marriage of Louis J. Barlow: Origins of FLDS Placement Marriage,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 40, no. 1 (Spring 2007): 102.

[17] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 4, 1844, in JSP, CFM:79.

[18] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:112.

[19] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:122.

[20] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:95–96.

[21] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:92.

[22] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11 and 5, 1844, in JSP, CFM:92, 82.

[23] Stan Larson, “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (1978): 200, 203. Smith’s views on religious liberty are also consistent between the April 7 King Follett discourse and his remarks in the Council of Fifty meeting four days later. In the April 7 sermon, he taught, “But meddle not with any man for his religion, for no man is authorized to take away life in consequence of religion. All laws and government ought to tolerate and permit every man to enjoy his religion, whether right or wrong. There is no law in the heart of God that would allow anyone to interfere with the rights of man. Every man has a right to be a false prophet, as well as a true prophet.” Larson, “King Follett Discourse,” 200. At the April 11 council meeting, he declared, “Nothing can reclaim the human mind from its ignorance, bigotry, superstition &c but those grand and sublime principles of equal rights and universal freedom to all men. . . . Nothing is more congenial to my feelings and principles, than the principles of universal freedom and has been from the beginning. . . . Hence in all governments or political transactions a mans religious opinions should never be called in question. A man should be judged by the law independant of religious prejudice.” Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:100–101.

[24] Mason, “God and the People,” 373–74.

[25] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:128.

[26] George M. Marsden, Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 15; see also Nathan O. Hatch, The Democratization of American Christianity (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989), esp. chaps. 1–2; and James Turner, Without God, without Creed: The Origins of Unbelief in America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1985), 62, 104–9.

[27] George M. Marsen, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 91.

[28] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:101.

[29] I explore these problems with theodemocracy at greater length in “God and the People,” 363–75.

[30] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:100.