The Council of Fifty and the Search for Religious Liberty

W. Paul Reeve

W. Paul Reeve, “The Council of Fifty and the Search for Religious Liberty,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 181-190.

W. Paul Reeve is a professor of history and the director of graduate studies in history at the University of Utah. He is the author of Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (2015).

On July 22, 2014, I received a brief email from Peggy Fletcher Stack, the award-winning religion reporter at the Salt Lake Tribune: “Paul, I am doing a short piece on Mormon pioneers for Thursday. Would you be willing to send me three surprising or intriguing facts about the pioneers and the trek that most people don’t know? I don’t need anything lengthy, just a paragraph on each.”

In response, I sent Peggy the following paragraph:

Considering the way in which some Pioneer Day talks in Mormon congregations sometimes conflate American patriotism with the Mormon arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, it seems evident that most Mormons today don’t realize the depth of mistrust and resentment some Mormon pioneers harbored toward the United States in 1846 and 1847. When the Mormons arrived in the Great Basin, they were actually arriving in northern Mexico. They crossed an international border and were fleeing the United States. The U.S. war with Mexico was ongoing. When some Mormons first learned of that war, they hoped Mexico would win. Pioneer Hosea Stout, for example, wrote in his diary, “I confess that I was glad to learn of war against the United States and was in hopes that it might never end untill they were entirely destroyed for they had driven us into the wilderness & was now laughing at our calamities.”[1]

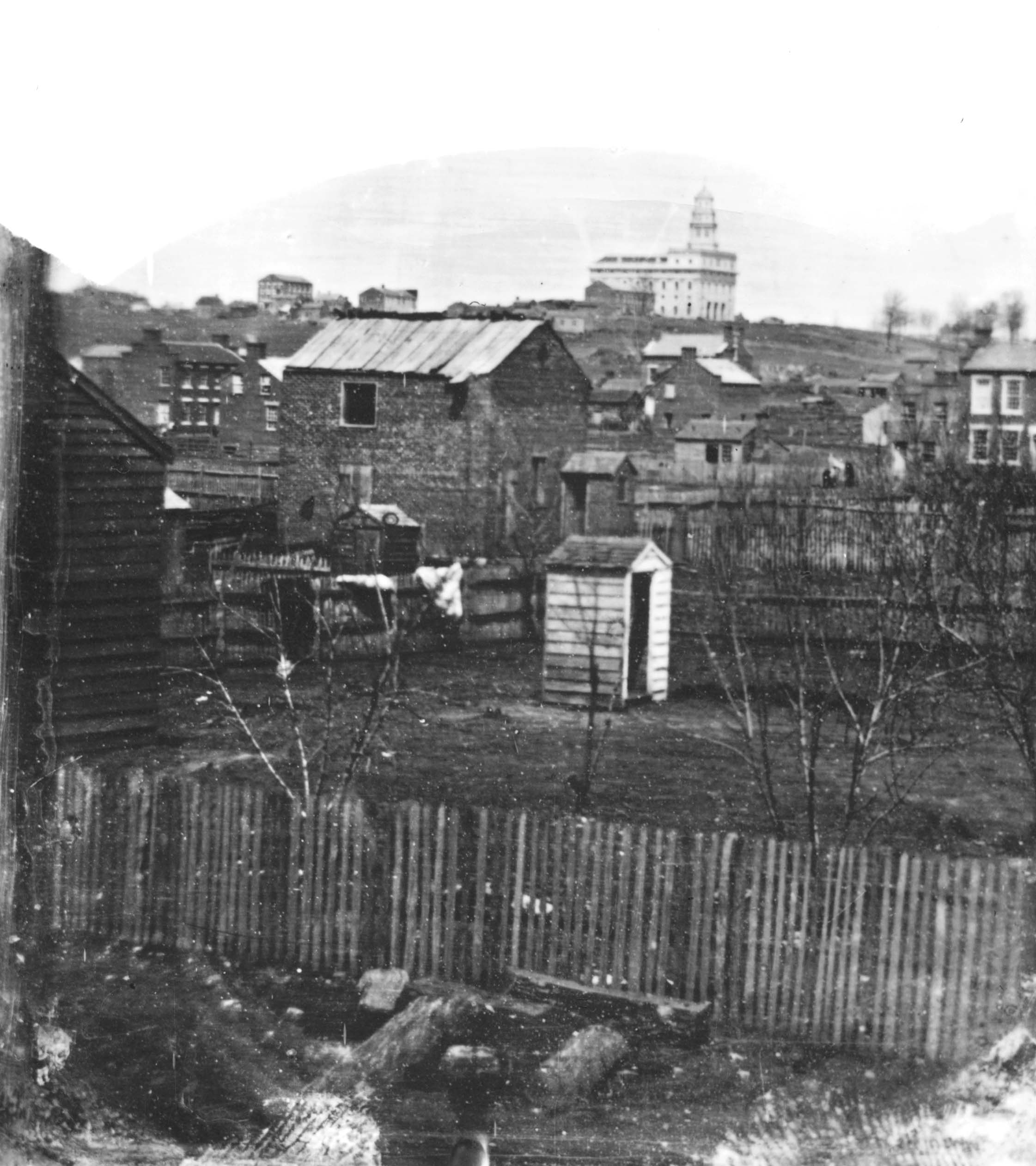

Nauvoo, Illinois, 1846. Glass plate negative made by Charles W. Carter of original daguerreotype by Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Nauvoo, Illinois, 1846. Glass plate negative made by Charles W. Carter of original daguerreotype by Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

After Stack’s story appeared in print and was subsequently passed around on Facebook, a bit of a dustup ensued.[2] A few people on Facebook wanted me to know that their Mormon pioneer ancestors were loyal Americans and that I had done them a disservice in the way that I had characterized the mistrust and resentment that some pioneers harbored toward the United States. After now having read the Council of Fifty minutes, if I had to answer Stack’s request today, I would suggest that my original answer, if anything, understated the mistrust and resentment some Mormons bore toward the United States. I would amplify the degree and depth of mistrust—and even outright rejection—of the United States and its Constitution that animated the Council of Fifty’s attitude.

A Previously Glossed-Over Period

In terms of an overall assessment of the council minutes, let me state that while some students of the Mormon past might be disappointed in the Council of Fifty minutes because they do not contain salacious evidence that might bring Mormonism to its knees, what I found was engaging and even sometimes riveting. It was as if I had a front-row seat as I watched the tragic unraveling of the Mormon community at Nauvoo. The time period covered in the minutes is significant. The two years from 1844 to 1846 seem so crucial, yet they fall between the cracks in terms of how historians have typically told the Mormon story.

Traditionally, historians end their discussion of the early era of Mormonism with Joseph Smith’s murder in June 1844 and then begin a discussion of the Great Basin era with Brigham Young’s departure from Nauvoo in February 1846 or Young’s arrival in the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847. If for no other reason, the Council of Fifty volume is essential for its fascinating and insightful lens—from an administrative perspective—into the two years that historians of the Mormon past typically only gloss over or ignore altogether. The unease and ongoing tension with old settlers in Hancock County sometimes drip from the pages as does the Latter-day Saint leadership’s efforts at finding a new place of refuge for the Saints. If readers are able to set aside their knowledge of how the story plays out and immerse themselves in the minds of council members who were not privy to that knowledge, the bleakness and even desperation of the Saints’ precarious situation from 1844 to 1846 is powerfully embodied in these minutes.

Resentment and Anger toward US Government

I felt the depth of council members’ despair over a continued inability to find judicial, executive, or legislative justice for the wrongs they had endured, including the murder of their leaders Hyrum and Joseph Smith. I was reminded of Alexis de Tocqueville’s assessment of one of the inherent weaknesses he found in American democracy, something he called the tyranny of the majority:

What I most criticize about democratic government as it has been organized in the United States, is not its weaknesses as many people in Europe claim, but on the contrary, its irresistible strength. And what repels me the most in America is not the extreme liberty that reigns there; it is the slight guarantee against tyranny that is found.

When a man or a party suffers from an injustice in the United States, to whom do you want them to appeal? To public opinion? That is what forms the majority. To the legislative body? It represents the majority and blindly obeys it. To the executive power? It is named by the majority and serves it as a passive instrument. To the police? The police are nothing other than the majority under arms. To the jury? The jury is the majority vested with the right to deliver judgments. The judges themselves, in certain states, are elected by the majority. However iniquitous or unreasonable the measure that strikes you may be, you must therefore submit to it or flee. What is that if not the very soul of tyranny under the forms of liberty?[3]

The Council of Fifty minutes made Tocqueville’s point real to me in a way that academic histories of Mormonism have not been able to do. Joseph Smith was especially concerned that the US Constitution did not protect minority rights. “There is only two or three things lacking in the constitution of the United States,” Smith contended, and it was the guarantee of rights and freedom for all, regardless of religious affiliation. He was dismayed that the federal government refused to intervene on behalf of Mormon property rights and religious liberty in Missouri. He wished that the Constitution required “the armies of the government” to enforce “principles of liberty” for all people, not merely the Protestant majority. He advocated severe penalties for a “President or Governor who does not do this,” suggesting that “he shall lose his head” or that “when a Governor or president will not protect his subjects he ought to be put away from his office.”[4] The failure of state or federal governments to address Mormon grievances clearly bothered Smith and was a prime motivator in his appointing a committee from among the council to draft a new constitution. That the committee’s efforts failed to produce a viable document testifies to the difficulties of constitution writing in general and to the challenges of writing specific guarantees against oppression toward marginalized groups. That a committee attempted such a feat affirms the depth of despair Mormon leaders felt at their status as a religious minority and the gravity of their perception that the US Constitution had failed them.

Joseph Smith compensated for the lack of liberty he saw in the US Constitution with an expansive vision of religious freedom at Nauvoo and for his proposed kingdom of God on earth. He included as members in the Council of Fifty those of other faiths or of no faith as an explicit demonstration of his views. He stated on April 11, 1844, that there were men (three total) admitted to the council who were not Latter-day Saints and who “neither profess any creed or religious sentiment whatever.” They were admitted to the council, in part, to demonstrate that “in the organization of this kingdom men are not consulted as to their religious opinions or notions in any shape or form whatever and that we act upon the broad and liberal principal that all men have equal rights, and ought to be respected, and that every man has a privilege in this organization of choosing for himself voluntarily his God, and what he pleases for his religion.”[5]

For Joseph Smith, it was not enough to merely tolerate people of other faiths or of no faith. Religious bigotry had no place in his worldview. He stated, “God cannot save or damn a man only on the principle that every man acts, chooses and worships for himself; hence the importance of thrusting from us every spirit of bigotry and intolerance towards a mans religious sentiments, that spirit which has drenched the earth with blood.” He called the council to witness that “the principles of intollerance and bigotry never had a place in this kingdom, nor in my breast, and that he is even then ready to die rather than yeild to such things. Nothing can reclaim the human mind from its ignorance, bigotry, superstition” he insisted, “but those grand and sublime principles of equal rights and universal freedom to all men.”[6] Joseph Smith and other members of the council came to believe that the US Constitution had failed the Latter-day Saints on this count—that their rights had not been protected. Thus they needed to draft a new constitution to rectify this inadequacy.

Devotion to the Nation

Despite the substantial resentment manifested in the Council of Fifty minutes toward the United States and its Constitution, council members also demonstrated an ongoing devotion to the nation. Considerable paradox is thus bound up in the minutes and in the hearts of its members. Under Joseph Smith’s leadership, the council “agreed to look to some place where we can go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California.”[7] Council members also “spoke very warmly” about “forming a constitution which shall be according to the mind of God and erect it between the heavens and the earth where all nations might flow unto it.”[8] At the same time, the council petitioned the US Congress to authorize Joseph Smith to “raise a company of one hundred thousand armed volunteers” to protect and facilitate US western expansion. Such a plan, the council suggested, would demonstrate Joseph Smith’s “loyalty to our confederate Union, and the constitution of our Republic.”[9] Joseph Smith also ran for president of the United States, and council members left Nauvoo on electioneering missions. Under Brigham Young’s leadership, council members talked about declaring themselves an independent nation even as the council drafted letters to every governor of every state in the nation asking if each governor might be willing to accept Latter-day Saints as a group of religious refugees in his respective state. Only the governor of Arkansas, Thomas S. Drew, wrote to Young in response. Drew claimed that he was unable to help and that the Mormons would be better off with their proposed move west.[10]

Perhaps these paradoxes foreground the tension that US Mormons continue to exhibit in the twenty-first century, with their desire to both belong and to be distinct. Perhaps that desire is a holdover from a much more fraught historical climate in the mid-to-late 1840s that ultimately propelled Mormons outside of the United States altogether and then put them at odds with the American nation for the rest of the century. As William W. Phelps said in one council meeting, he was in favor of “letting the United States and the British governments alone, we are better without them.”[11] It was a sentiment that continued to animate Mormon interactions with the nation on occasion. By the early twentieth century, Mormon leaders were ready to move toward accommodation, yet an underlying wariness still sometimes stirred both sides.

The West

My final impression from reading the minutes highlights the power that the American West (or what would become the American West) had over the imaginations of members of the Council of Fifty. The council’s very organization centered on the idea that Mormons needed to find a new location for Mormon settlement (initially, the search was for an additional location for Mormons—another gathering place not to replace Nauvoo but to supplement it, with some early discussion and efforts focused on Texas as a place where Mormons with slaves might gather to avoid the problems that moving to a northern state might present for slaveholding converts). Oregon and California were also places that captured the council’s imagination.

The historian Frederick Jackson Turner talked about the West as a safety valve—a location that allowed the crowded cities and factories of the East to release the pressure of America’s growing industrialization by offering free land and a new destiny in the West.[12] The Council of Fifty viewed the West as a safety valve of its own making. What council members sought to flee was not the growing squalor of industrial centers but a government that failed to protect minority rights. The West of their imagination was a place outside the bounds of firm state control, and for those reasons they zeroed in on Oregon, Texas, and Alta, or Upper, California. Over the chronological course of the minutes, council members for various reasons became less enthused about Texas and Oregon and more focused on California (an expansive geographic term at the time that encompassed the northern Mexican frontier, including the Great Basin). “The sooner we are where we can plant ourselves where there will be no one to say [that] they are [the] old settlers the better,” George A. Smith said on September 9, 1845.[13] At that same meeting, Brigham Young stated that “it has been proved that there is not much difficulty in sending people beyond the mountains. We have designed sending them somewhere near the Great Salt Lake.”[14]

Historians have long known of the advanced preparations of the Mormons for their removal west, especially their foreknowledge of the resources that the West had to offer and of the potential sites for a future relocation.[15] The Council of Fifty minutes add detail and a more concrete timeline to that knowledge. As early as September 1845, Young had zeroed in on the Great Salt Lake. Sometimes, stories that circulate in popular Mormon culture suggest that the Saints were driven from their homes in Illinois and wandered aimlessly westward, not knowing their destination until, on July 24, 1847, Brigham Young declared that the Salt Lake Valley was “the right place.” Young, in fact, arrived two days after the initial Mormon migrants entered the valley on July 22. He joined that vanguard group on July 24 at their camp between present-day Third and Fourth South and Main and State Streets, where the beginnings of the initial Mormon settlement were already under way. Young’s declarative statement that day was thus a confirmation of a decision already made, something Young had contemplated with the Council of Fifty as early as the fall of 1845.[16]

Council members were also purposefully looking for a place outside of firm governmental control for their settlement, and northern Mexico fit that bill. They were fully aware that they were leaving the United States and crossing an international border. Mexico’s lack of direct dominion over its northern frontier was what made it so desirable to the Saints. Erastus Snow observed on March 22, 1845, that “the only difficulty there appears to be in the way of our locating in California is the Mexican government, and he has no fears about them. . . . He knows the Mexican government is weak, and they have never taken measures to place themselves in a situation of defence: They are too weak to maintain themselves against their own enemies in their midst. Every information he has been able to get goes to satisfy him that there is a mere form of government but not much power.”[17] As Snow viewed it, the Great Basin existed in a power vacuum, which made it an attractive destination for the Saints, who were looking for a place to establish a religious kingdom without the same type of outside interference that had worked to their disadvantage in Missouri and Illinois.

Conclusion

The Council of Fifty minutes, in summary, offer an important administrative perspective into a crucial two years in Mormon history. They highlight the mounting tension between the Saints and the American nation and offer a much longer view of events leading up to the Utah War of 1857–58. Future histories of that war will need to account for the attitudes and perspectives toward the federal government brewing among Mormon leaders in the 1840s as the beginnings of a fracturing relationship that continued to deteriorate through the 1850s. These insights and many more will give students of Mormon history much to contemplate as they pore over the Council of Fifty minutes in search of new understanding.

Notes

[1] Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844–1861, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964), 1:163–64; see also John F. Yurtinus, “‘Here Is One Man Who Will Not Go, Dam’um’: Recruiting the Mormon Battalion in Iowa Territory,” BYU Studies 21, no. 4 (Fall 1981): 475–87.

[2] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “This Is the Place for Facts You Might Not Know about Mormon Pioneers,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 24, 2014, http://

[3] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America: Historical-Critical Edition of De la démocratie en Amérique, ed. Eduardo Nolla, trans. James T. Schleifer (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2010), 2:413–14.

[4] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 101, (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[5] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:97.

[6] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:97, 100.

[7] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:40.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:42.

[9] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 26, 1844, in JSP, CFM:68, 69.

[10] JSP, CFM:389.

[11] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1845, in JSP, CFM:409.

[12] George Rogers Taylor, The Turner Thesis Concerning the Role of the Frontier in American History, rev. ed., Heath New History Series (Boston: Heath, 1956).

[13] Council of Fifty, Minutes, September. 9, 1845, in JSP, CFM:476.

[14] Council of Fifty, Minutes, September. 9, 1845, in JSP, CFM:472.

[15] Lewis Clark Christian, “Mormon Foreknowledge of the West,” BYU Studies 21, no. 4 (Fall 1981): 403–15.

[16] W. Randall Dixon, “From Emigration Canyon to City Creek: Pioneer Trail and Campsites in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65 (Spring 1997): 155–64.

[17] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 22, 1845, in JSP, CFM:354.