The Council of Fifty and Joseph Smith's Presidential Ambitions

Spencer W. McBride

Spencer W. McBride, “The Council of Fifty and Joseph Smith's Presidential Ambitions,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 21-30.

Spencer W. McBride is a historian whose research interests include the intersections of religion and politics in early America. He is a volume editor with the Joseph Smith Papers Project and the author of Pulpit and Nation: Clergymen and the Politics of Revolutionary America (2016).

Discussion of Joseph Smith’s 1844 presidential campaign elicits a fairly standard set of questions. Was Joseph Smith serious about his presidential ambitions or was he merely a protest candidate running to raise awareness of the Mormons’ plight? Did Smith and his fellow Church leaders believe that he could actually win the election? If they did, how confident were they that the campaign strategy they had devised would carry Smith into the White House? For decades, scholars defended their respective answers to these questions with relatively limited source materials, reliant instead on their own interpretations of the few surviving statements that Smith and his close associates made concerning the seriousness of his campaign.[1] But the minutes of the Council of Fifty provide scholars with new source material on the presidential campaign that, when considered with sources previously known, better equips them to examine these key questions.

The Council of Fifty minutes reveal that Smith was more than a protest candidate—that is, that he and other Church leaders viewed an electoral triumph as possible, even if unlikely. While council members were certain that the campaigning efforts of Church leaders throughout the United States were essential to Smith’s success, they appear to have believed that his candidacy would ultimately require some form of divine intervention in order to succeed. Yet the most significant aspect of Smith’s presidential campaign illuminated by the Council of Fifty minutes is that the campaign was merely one possible avenue by which Latter-day Saints could attempt to obtain federal redress and protection while awaiting the establishment of the political kingdom of God. Smith’s run for the American presidency thus represents a nexus of idealism and pragmatism as well as an unusual combination of providentialism and contingency planning.

Reasons for Smith’s Campaign

Smith launched his presidential campaign on January 29, 1844, when he accepted the nomination made by Willard Richards, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, in a meeting of Church leaders.[2] A few days later, after a public reading of his campaign pamphlet, General Smith’s Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States, Smith justified his candidacy to his followers. “I would not have suffered my name to have been used by my friends on any wise as president of the United States or Candidate for that office,” he explained, “if I and my friends could have had the privilege of enjoying our religious and civil rights as American citizens.” But since he felt that his followers had been denied those rights, he declared, “I feel it to be my right and privilege to obtain what influence and power I can lawfully in the United States for the protection of injured innocence.” In this same meeting, Smith called on “every man in the city who could speak” to go “throughout the land to electioneer,” insisting that “there is oratory enough in the church to carry me into the presidential chair the first slide.”[3]

While these words elucidate the reasons Smith was seeking the presidency, they do not clearly establish whether he was serious about the race or if he thought he could win. Indeed, various men and women have campaigned for the presidency without any expectation—or desire—to win but rather to raise awareness for the issues that mattered most to them and their followers.[4] In Smith’s case, his presidential ambitions could bring the plight of the Mormons—first in Missouri and then in Illinois—to the attention of the American public as well as to savvy politicians who recognized the potential electoral boost they might receive as a result of supporting the Mormon’s petitioning efforts with state and federal governments.

The Council of Fifty’s Role in Joseph Smith’s Campaign

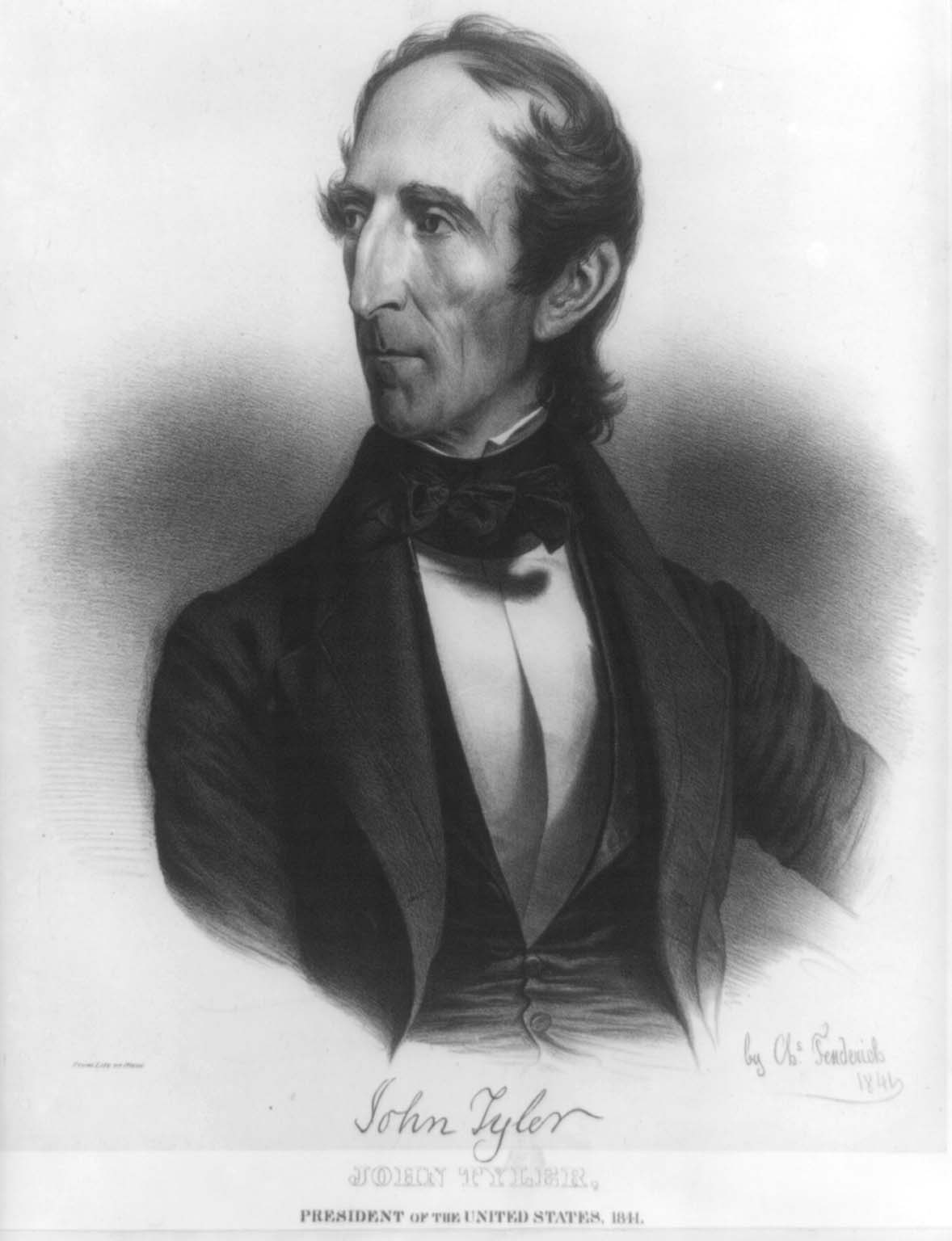

John Tyler was president of the United States at the time that Joseph Smith announced his own presidential campaign. Lithograph by Charles Fenderich. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

John Tyler was president of the United States at the time that Joseph Smith announced his own presidential campaign. Lithograph by Charles Fenderich. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

The Council of Fifty assumed much of the responsibility for managing Smith’s campaign. Committee members helped build the campaign message around the themes set forth in General Smith’s Views, titling their independent presidential ticket “Jeffersonianism, Jeffersonian Democracy, free trade and Sailors rights, protection of person & property.”[5] They also selected and invited men to be the vice presidential candidate on Smith’s independent ticket. Their first choice was James Arlington Bennet of New York, who had corresponded with Smith for years and joined the church in 1843. However, after council members discovered—incorrectly—that Bennet was born in Ireland (and therefore ineligible for the vice presidency), they opted to invite Solomon Copeland, a friend to Church members in Tennessee, to assume that place on the ticket. When Copeland failed to respond to the council’s invitation, council members decided to name Sidney Rigdon, a counselor in the Church’s First Presidency, as Smith’s running mate.[6]

More Than a Protest Candidate

The view of Smith as a mere protest candidate arose in the weeks immediately following his nomination, even among some of the Mormon leader’s close friends and supporters. For instance, in responding to the invitation to run for vice president on Smith’s ticket, Bennet wrote to Willard Richards that “if you can by any Supernatural means Elect Brother Joseph President of these [United] States, I have not a doubt that he would govern the people and administer the laws in good faith, and with righteous intentions, but I can see no Natural means by which he has the slightest chance of receiving the votes of even a one state.” Considering other possible reasons for the campaign, Bennet continued: “If the object of [Smith’s] friends be to aid the Cause of Mormonism in foreign lands, or in this Country among a certain class of persons . . . then I think they are somewhat in the right track, but if they are aiming in reality at that high office then I must say that at present they, in my opinion, are on a wild goose chase.”[7]

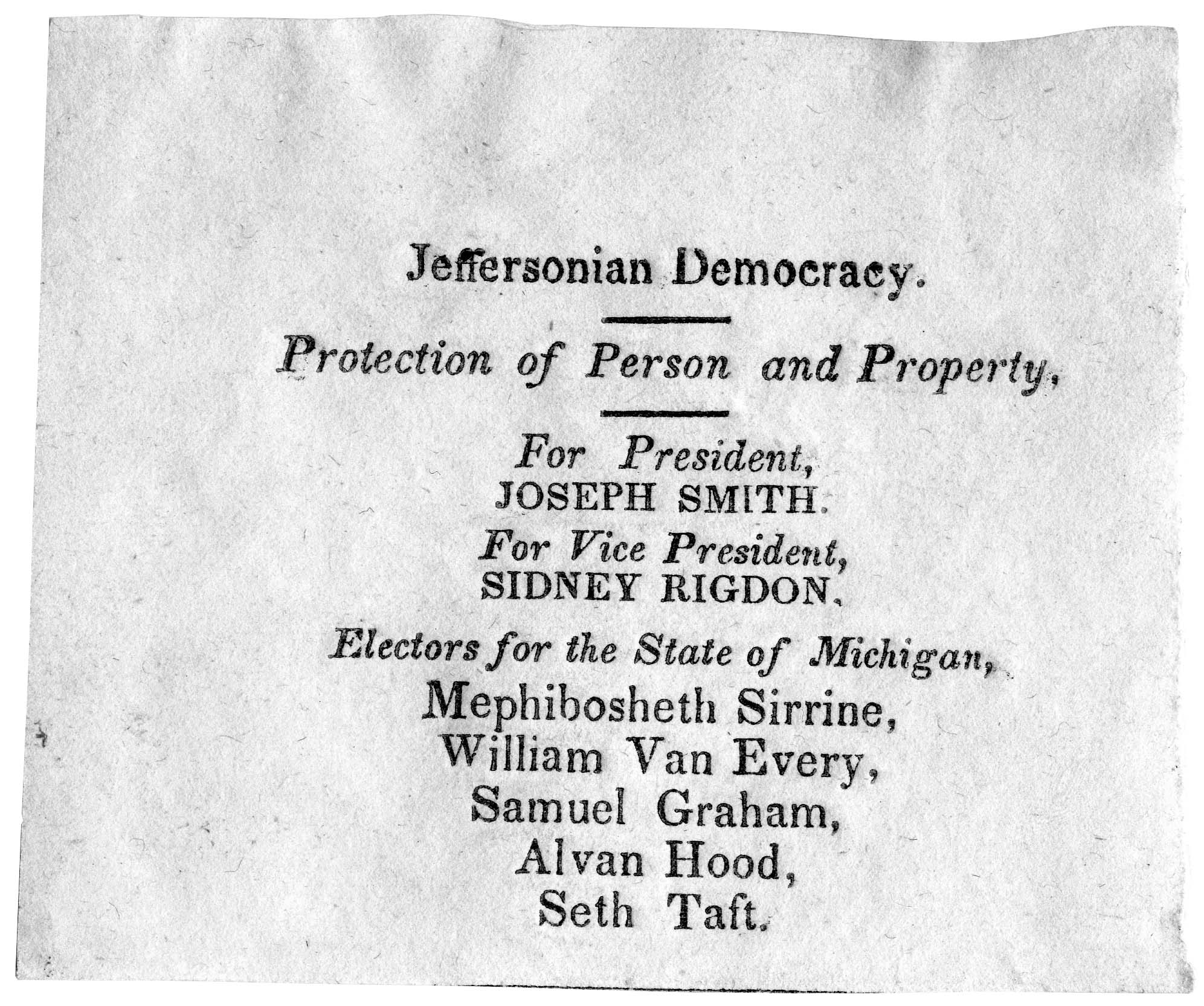

Men campaigning for Joseph Smith issued tickets like this for use as ballots in the presidential election. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Men campaigning for Joseph Smith issued tickets like this for use as ballots in the presidential election. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Richards responded to Bennet in June. “Your views about the nomination of Gen. Smith for the presidency are correct,” he wrote. “We will gain popularity and extend influence, but this is not all, we mean to elect him, and nothing shall be wanting on our part to accomplish it.”[8] Richards clearly acknowledged the potential benefits of the presidential campaign toward raising awareness of the Mormons’ plight but insisted that those benefits did not exclude an expectation of electoral success. Furthermore, his insistence that “there would be nothing wanting on our part to accomplish it” suggests that Smith’s election would require help from an outside—even a divine—source.

Still, protest candidates do not always publicly identify themselves as such. That Smith and his fellow Mormon leaders were serious in putting his name forth as a presidential candidate is demonstrated by their efforts to select electors in a formal convention. At a meeting of the Council of Fifty on April 25, 1844, the council decided to “have delegates in all the electoral districts and hold a national convention at Baltimore,” where both the Whig and Democratic Parties were holding their respective nominating conventions that May. Smith stated that “the easiest and the best way to accomplish the object in view is to make an effort to secure the election at this contest.”[9] Indeed, at a conference of the Church just two weeks earlier, Church leaders had called for members “to preach the Gospel and Electioneer” for Smith. Nearly three hundred men volunteered, and volunteers were subsequently assigned to preach and campaign in specific states in which they would “appoint conferences . . . to get up electors who will go for [Smith] for the presidency.”[10]

If the Church was promoting Smith’s candidacy simply to raise public awareness for the plight of its members, then electors were superfluous. While it was common in the earliest American presidential elections for the legislatures of many states—and not the people—to select the men who eventually cast their votes in the Electoral College, by the 1840s only South Carolina still used this method to select its electors. The rest of the states had moved to a system in which the winner of the state’s popular vote received the support of all of the electors allotted to it.[11] This meant that the selection of electors was a technical aspect in a strategy to actually elect someone president, an aspect that had little significance in a campaign focused solely on building public support for a cause. By designating a slate of electors in each state, Church leaders created an electoral infrastructure designed to convert popular support into the votes that could actually carry a person to the presidency. Of course, without popular support, that infrastructure would be useless.

The Council of Fifty’s emphasis on securing electors in each state should Smith win the popular vote in those places illuminates the way the council viewed the presidential campaign. To council members, Smith was not merely a protest candidate. They thought that he could win and made the necessary technical arrangements to facilitate such an event should large numbers of Americans in each state cast their votes for him. After all, no amount of popular votes or divine intervention could make Smith president without the requisite number of electoral votes.

Alternative Solutions

That Mormon leaders believed Smith could win the presidency did not necessarily mean that they believed he would win. It was merely one possible avenue through which they believed divine providence could work to restore the United States to its privileged place in God’s grand plan for the world and to help the Saints reclaim their promised land of Zion. Despite Richards’s insistence to James Arlington Bennet that the reason Church leaders were promoting Smith’s candidacy for president was “because we are satisfied . . . that this is the best or only method of saving our free institutions from total overthrow,” the Council of Fifty members were exploring several possible avenues that might eventually lead them to the peace and prosperity in the land they believed that God had promised to them while still remaining citizens of a country that had hitherto condoned their ill treatment.[12] For instance, the Council of Fifty petitioned the federal government to authorize Smith to form and lead a military force of one hundred thousand men to protect Texas and Oregon from foreign invasion. If Congress had agreed to the plan, Smith would presumably have become a general in the US Army—certainly a promotion from his role as lieutenant general of the Nauvoo Legion. The United States would have a force dedicated to protecting its interests in Texas and Oregon, and Smith would have an army at his command to ward off mobs that threatened the Mormons in Nauvoo.[13]

In addition, the council dispatched Heber C. Kimball and Lyman Wight to Washington, DC, in May 1844 to petition Congress for “a liberal grant of lands in one of the Territories of the United States, to be located in such manner as not to deprive any previous settler of any just right or claim.” They asked that the government either give them the land outright or sell it to them on favorable terms of credit. Such an arrangement would have provided the Mormons a degree of isolation ideal for preventing future outbreaks of violence with non-Mormon neighbors, like those that occurred in Missouri during the 1830s or that appeared imminent in western Illinois in 1844.[14]

The White House, circa 1846. Daguerreotype by John Plumbe. Courtesy of Library Congress, Washington, DC.

The White House, circa 1846. Daguerreotype by John Plumbe. Courtesy of Library Congress, Washington, DC.

Yet another proposed solution was that the federal government designate Nauvoo a territory. In such a scenario, the city would effectively secede from Illinois and fall under the protection and direct authority of the federal government. Smith explained in an April meeting of the Council of Fifty that such an arrangement would “set us everlastingly free, and give us the United States troops to guard us and protect us from any invasion.”[15] However far-fetched and unlikely the proposal may have been, territorial status would have empowered Smith and his followers to exercise greater sovereignty in governing their society in nonecclesiastical matters, the kind of sovereignty that was at that time eliciting suspicion and opposition from several prominent figures in Illinois politics.

Smith’s election or any of these other plans would have provided substantial relief to the Mormons amid the growing hostility they felt from their fellow citizens in Illinois. Yet the Council of Fifty members anticipated that all their plans to remain in the United States on their own terms might fail. Accordingly, they planned for an exodus to a place where they could establish themselves as a sovereign people.[16] In the end, Smith was murdered several months before Election Day, and Congress never seriously considered any of the Mormon leadership’s proposed plans. Moving out of the country thus appeared to many council members as the plan God intended for them to pursue.

Conclusion

Joseph Smith was not merely a protest candidate campaigning for the sole purpose of raising awareness of the poor treatment of the Mormons in a country that claimed to value religious liberty. While parties operating outside the mainstream Whig and Democratic parties often held conventions to nominate candidates, holding conventions designed to select electors in each state was less common. Still, as the intent of the Council of Fifty was to “leave nothing wanting” on its part where the election was concerned, council members simultaneously planned for other contingencies, working out an array of potential paths to the building up of the kingdom of God on earth, a kingdom that they believed they were destined to lead.

Notes

[1] Several scholars have examined Smith’s campaign and offered their respective opinions on how serious Smith was about his presidential ambitions. Fawn Brodie wrote that Smith “suffered from no illusions about his chances of winning the supreme political post in the nation. He entered the ring not only to win publicity for himself and his church, but most of all to shock the other candidates into some measure of respect.” Fawn Brodie, No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, 2nd ed. (New York: Knopf, 1971), 362. Richard Bushman portrays Smith’s campaign largely as a gesture designed to attract publicity to the Church and its petitioning efforts but acknowledges that “with a large field of candidates and no clear favorite,” Smith “may have thought he could gain votes through convert baptisms and steal the victory in a split vote.” Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 515. In setting forth their conspiracy theory that Smith was assassinated in order to elect Henry Clay president, Robert S. Wicks and Fred R. Foister portray Smith as a serious candidate with a real chance to win. Robert S. Wicks and Fred R. Foister, Junius and Joseph: Presidential Politics and the Assassination of the First Mormon Prophet (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2005). John Bicknell asserts that Smith “understood fully that he would not be elected president” but that “the campaign afforded him a chance to spread the word about Mormonism and put its case before the people and their leaders.” John Bicknell, America 1844: Religious Fervor, Westward Expansion, and the Presidential Election That Transformed the Nation (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015), 48–49; see also Newell G. Bringhurst, “Reflections on a Roundtable Colloquium Dealing with Joseph Smith’s 1844 Campaign for U.S. President,” John Whitmer Historical Society Journal 22 (2002): 153–58.

[2] Joseph Smith, Journal, January 29, 1844, in Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 170.

[3] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, February 8, 1844, in Scott G. Kenney, ed., Wilford Woodruff’s Journal: 1833–1898 Typescript (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1983), 2:349.

[4] Notable examples of American protest candidates include James G. Birney, the abolitionist and Liberty Party candidate in the presidential elections of 1840 and 1844, and Eugene V. Debs, the labor advocate and Socialist Party candidate in five of the six presidential elections between 1900 and 1920. On Birney and the Liberty Party, see Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, and Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 78–82; and Vernon L. Volpe, “The Liberty Party and Polk’s Election,” The Historian 53, no. 4 (Summer 1991): 691–710. On Debs and the Socialist Party, see Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982).

[5] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 90 (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[6] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 21 and May 6, 1844, in JSP, CFM:57, 157–59.

[7] James Arlington Bennet to Willard Richards, April 14, 1844, Willard Richards Journals and Papers, 1821–1854, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter CHL).

[8] Willard Richards to James Arlington Bennet, June 20, 1844, Willard Richards Journals and Papers, 1821–1854, CHL.

[9] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 25, 1844, in JSP, CFM:133–34. Ultimately, a convention in Nauvoo on May 17, 1844, resolved to hold the proposed “National Convention at Baltimore” on July 13. However, Smith’s murder on June 27 stripped the event of its core purpose. See JSP, CFM:133n404.

[10] Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes, April 9, 1844, CHL; Conference Assignments, Nauvoo Neighbor, April 17, 1844, [2]; JSP, CFM:134n406.

[11] Robert G. Dixon Jr., “Electoral College Procedure,” The Western Political Quarterly 3, no. 2 (June 1950), 215.

[12] Willard Richards to James Arlington Bennet, June 20, 1844, Willard Richards Journals and Papers, 1821–1854, CHL.

[13] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 26, 1844, in JSP, CFM:66–72. Empowering the federal government to send troops into individual states to protect religious minorities from mob violence without the formal request of a state’s governor was a prominent plank in Smith’s campaign platform. See Joseph Smith, General Smith’s Views on the Powers and Policy of the Government of the United States (Nauvoo, IL: John Taylor, 1844), 10.

[14] Lyman Wight and Heber C. Kimball, Petition to US Senate and House of Representatives, 1844, Record Group 46, Records of the US Senate, National Archives, Washington, DC; JSP, CFM:162n516.

[15] Nauvoo City Council, Minutes, December 8 and 21, 1843, and February 12, 1844, CHL; Hyrum Smith et al., Memorial to the US Senate and House of Representatives, December 21, 1843, Record Group 46, Records of the US Senate, National Archives, Washington, DC; Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:127–28.

[16] For more on the discussion in the Council of Fifty about relocating the main body of the Church to Oregon, see Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:267—68; and Letters from Orson Hyde, April 25 and 26, 1844, in JSP, CFM:181–84. On the discussion in the council about relocating the main body of the Church to Texas, see Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:115–16, 127–28.