To Carry Out Joseph's Measures is Sweeter to Me Than Honey

Brigham Young and the Council of Fifty

Matthew J. Grow and Marilyn Bradford

Matthew J. Grow and Marilyn Bradford, “To Carry Out Joseph's Measures is Sweeter to Me Than Honey,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 105-118.

Matthew J. Grow, director of publications for the LDS Church History Department, is a historian specializing in Mormon history. Grow coauthored a biography of Parley P. Pratt with Terryl Givens. He formerly directed the Center for Communal Studies housed at the University of Southern Indiana.

Marilyn Bradford is a research assistant at the Church History Department, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She graduated with a degree in history from the University of California, Berkeley in 2015 and wil be pursuing a master's in history education.

[1] Seven months after the death of Joseph Smith, Brigham Young reconvened the Council of Fifty. Indicating his view of the council and his own role in succeeding Smith as chairman, Young stated that he intended to “have the priviledge of carrying out Josephs measures.” Indeed, he continued, “To carry out Josephs measures is sweeter to me than the honey or the honey comb.” Young hoped to enact the plans and priorities of Joseph Smith, who had established the Council of Fifty to “go and establish a Theocracy either in Texas or Oregon or somewhere in California” and to work “for the safety and salvation of the saints by protecting them in their religious rights and worship.”[2]

After the council’s reorganization, council member Orson Spencer cautioned Young, suggesting that he would also have to divert from Smith’s policies: “When Joseph was here he was for carrying out his (Josephs) measures, he now wants prest. Young as our head to carry out his own measures, and he believes they will be right whether they differ from Josephs measures or not. Different circumstances require different measures.”[3] This interchange between Young and Spencer, which occurred during one of the most difficult eras in Mormon history, illustrates Young’s dilemma: as the successor to Joseph Smith as leader of the Latter-day Saints, how to implement Smith’s vision while also retaining flexibility as new circumstances arose.

Though the minutes of the Council of Fifty were published as part of The Joseph Smith Papers, they arguably provide more insight into Brigham Young than Joseph Smith. During the era of the Nauvoo minutes, March 1844–January 1846, the council operated for a much longer period of time under Young than Smith—with meetings spanning eleven months for Young versus three for Smith. In addition, the minutes of the Young era tend to be much more detailed, capturing more of Young’s thoughts and the dynamics of the council. In fact, nearly 70 percent of the words in the Nauvoo minutes concern the Young era rather than the Smith era. Other records illustrating Young’s work as an administrator—such as minutes from the Quorum of the Twelve—also tend to be more fragmentary than the council’s minutes. As such, the council’s minutes give rich insights into Young’s personality, leadership style, and priorities.

Young and the Council under Joseph Smith

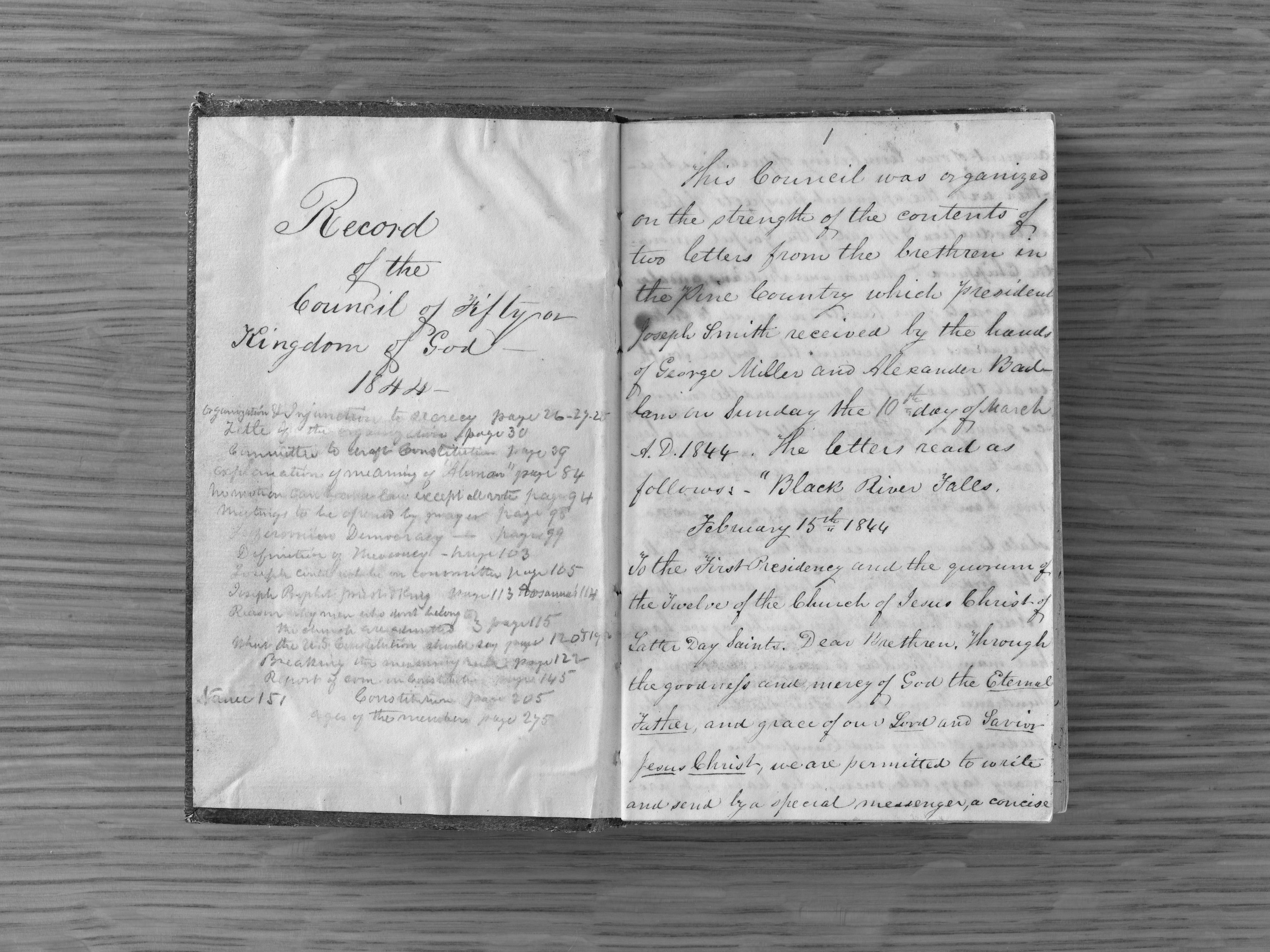

Brigham Young was an addressee of the February 15, 1844, letters that led to the formation of the Council of Fifty. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Brigham Young was an addressee of the February 15, 1844, letters that led to the formation of the Council of Fifty. Photograph by Welden C. Andersen. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Young was a member of the Council of Fifty during its entire existence in Nauvoo. Along with Smith and Willard Richards, Young was one of the addressees of the letters sent from Saints in Wisconsin Territory that served as the catalyst to organize the council. At the organizational meeting of the council, Young is listed after only Joseph and Hyrum Smith among the members, an indication of the increasing importance of his role as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.[4] Young recorded in his journal, “Met in councel at Br. J. Smith store in company a bout 20 to orginise our Selves into a compacked Boddy for the futher advenment of the gospel of Christ.”[5]

Young appears to have spoken infrequently to the council at first, though the brief minutes of the opening meetings could obscure some of his participation. According to the records, he first spoke on March 21, when he seconded a motion from Joseph Smith that Erastus Snow serve a mission in Vermont.[6] Over the coming weeks, he became increasingly involved in making or seconding motions to the council, though he was not appointed to participate in any of the committees of the council.

During the first three months of the council, the minutes record two significant statements from Young, the first on April 5 and the second on April 18. In these remarks, Young articulated many themes that he would return to in future council meetings and that defined some of his core beliefs as a leader of the Church, including the necessity of revelation and prophetic leadership, the merging of Church and state (particularly as seen in Utah during the first decade of settlement), and the emphasis on individual freedom and autonomy.[7]

In these statements, Young emphasized the primacy of revelation over written laws, telling the council that he “thought when he came in this church he should never want to keep book accounts again, Why? He thought the law would be written in every mans heart, and there would be that perfection in our lives, nothing further would be needed.” Furthermore, he stated, “Revelations must govern. The voice of God, shall be the voice of the people.” According to Young, revelation was suited to a particular moment in time. He stated that he “supposed there has not yet been a perfect revelation given, because we cannot understand it, yet we receive a little here and a little there.” Young would “not be stumbled if the prophet should translate the bible forty thousand times over and yet it should be different in some places every time, because when God speake, he always speaks according to the capacity of the people.” In addition, Young taught that revelation would come after the people had done all they could: “When we had done all we were capable to do, we could have the Lord speak and tell us what is right.” Obeying God’s revelations would lead to further revelation: “When God sees that his people have enlarged upon what he has given us he will give us more.”[8]

Young also spoke of his views of Joseph Smith and of prophets in general. “God appointed him,” Young told the council. “We did not appoint him.” As such, Smith in his role as a revelator could “disagree with the whole church” because he “is a perfect committee of himself.” Indeed, Young stated, “It is the prerogative of the Almighty to differ from his subjects in what he pleases, or how, or when he pleases, and what will they do; they must bow to it, or kick themselves to death, or to hell.” However, Young continued, “If it was necessary, and we were where we could not get at the prophet, we could get the revelations of the Lord straight.”[9]

Young’s statements also indicated his vision of earthly governments as compared with the kingdom of God. He recalled the “exalted views” he felt at the first meeting of the council when Smith “stated that this was the commencement of the organization of the kingdom of God.” Though the kingdom of God was then just “in embryo,” Young believed that it would “send forth its influence throughout the nations” and the governments of the world would sink “into oblivion.” He gave his opinion that there was no distinction between the spiritual and the temporal: “No line can be drawn between the church and other governments, of the spiritual and temporal affairs of the church.” Joseph Smith, by contrast, saw a distinction between the “Church of God and kingdom of God,” asserting that the Church would govern in ecclesiastical matters while the kingdom would govern in civil matters. Nevertheless, a year later, Young reiterated that he saw this distinction less clearly than Smith, stating that he would “defy any man to draw the line between the spiritual and temporal affairs in the kingdom of God.”[10]

Finally, Young spoke of his strong belief in independence and autonomy: “Republicanism is, to enjoy every thing there is in heaven, earth or hell to be enjoyed, and not infringe upon the rights of another.” Later in 1844, William Smith referred to the “Mormon Creed” as “mind your own business.” That statement resonated with Young, who often repeated it during his long ministry. “To mind your own business,” Young later said, “incorporates the whole duty of man.”[11]

Young’s personality also comes through in these early council meetings. Known for the quality of his singing voice, Brigham often sang in public. One participant on the Camp of Israel (also known as Zion’s Camp) in 1834, Levi Hancock, recalled that Brigham’s duets with his brother Joseph “were the sweetest I ever heard in the Camps of Zion.”[12] On four occasions in April and May, Young sang a parody of the popular patriotic song “Hail Columbia” that had been composed by council member William W. Phelps. In addition, Young was evidently among the council members who were excused in the afternoon session of April 25 because they were performing in a popular German play—Pizarro; or, The Death of Rolla—that evening. Young also showed his ability to think quickly. On April 11, Joseph Smith became so animated while speaking on worldly and heavenly constitutions that he broke a two-foot ruler in half. Young quipped, “As the rule was broken in the hands of our chairman so might every tyrannical government be broken before us.”[13]

Young attended his last meeting of the council under Joseph Smith on May 6, after which he departed on an electioneering mission. He was in Peterborough, New Hampshire, when he received confirmation on July 16, 1844, that Joseph Smith had been killed. After gathering other apostles in the East, Young raced back to Nauvoo, where he and the other members of the Quorum of the Twelve took firm control over the Church organization. He continued many of the “measures of Joseph” over these months but did not immediately reorganize the Council of Fifty.[14]

Reorganization of the Council

On February 4, 1845, after receiving news that the Illinois legislature had revoked the Nauvoo municipal charter, the Council of Fifty met for the first time following Smith’s death. Young asked the other twenty-four men present “whether they are willing that I should take the place of brother Joseph as chairman.” The men spoke in order of seniority. Samuel Bent, the oldest man, set the tone of the responses that followed: “He rejoices in the opportunity of meeting once more and feels steadfast in the principles and rules of the council as laid down by our beloved brother Joseph. He feels that it would be highly satisfactory to him to have president Young take the place of brother Joseph as chairman and carry out Josephs measures.” Orson Pratt stated, “It is a thing selfevident that the president of the church stands at the head of this council.” William Clayton said, “We cannot carry out Josephs measures but by sustaining Brigham Young as our chairman, our head and successor of Joseph Smith.” Following the discussion, the council voted unanimously to sustain Young as “the standing chairman of this council and legal successor” to Smith. About a month later, council members unanimously received Young as “prophet, priest, and king to this kingdom forever after” as they had earlier received Joseph Smith.[15]

In addition to noting his own sustaining as leader of the council on February 4, Young reported in his journal that the council was “righted up & organized.” That day, the council sustained as members the twenty-five men present and an additional fifteen men absent that day. Three men—including Joseph and Hyrum Smith—had died since the council’s last meeting in May 1844. In addition, the council rejected eleven men on February 4, meaning that the membership stood at forty (fifty-four men had joined the council under Joseph Smith). The council dropped men seen as disloyal to Young and the Twelve Apostles, including Sidney Rigdon. While Young worked to reclaim individuals whose loyalty was in doubt—such as council members Lyman Wight and James Emmett, both of whom had led companies of Saints from Nauvoo over the objections of Young—he also did not want them in a confidential council.[16]

The council also dropped the three non-Mormons who had joined the council under Joseph Smith. It does not appear that the council rejected the men simply because they were non-Mormons. Of the three, one had been arrested for counterfeiting, one had been accused of threatening to “bring a mob on the church” around the time of Joseph Smith’s murder, and the third later recalled that he had a falling-out with the Saints after Smith’s death. However, no efforts were made to add any non-Mormons to the council. Rather, they were replaced—as were the other council members who had been dropped—by trusted Latter-day Saints over the next several weeks.[17]

How Young Operated the Council

The Council of Fifty met under Young’s direction in Nauvoo from February through May 1845 and then, following a summer recess, from September 1845 through January 1846. Young later reconvened the council in Winter Quarters and then in territorial Utah. The detailed council minutes in 1845 and early 1846 give insights into Young’s leadership approach for the thirty years that he led the Saints, including his stated reliance on revelation, his sometimes harsh rhetoric, and his focus on settlement and the temple. Young clearly felt the heavy weight of leading the Latter-day Saints during a perilous time. In describing his responsibility, he stated, “If men are set to lead a people it is not for them to consult and satisfy their own private feelings, but to use all the stratagem and cunning they are capable of to save the people.”[18]

In leading the council, Young referred both to his ability to receive revelation to guide the Latter-day Saints and his belief that Joseph Smith had established the agenda they should follow. “While Joseph was living,” he recalled, “it seems as though he was hurried by the Lord all the time, and especially for the last year.” In Young’s mind, “It seemed he laid out work for this church which would last them twenty years to carry out.” At the same time, Young was confident that he and the other apostles could carry the work forward: “When the Twelve have been separated from Joseph in England or the Eastern States or elswhere, I defy any man to point out the time when I was in the dark in regard to what should be done. . . . Some have been fearful that I would blunder in the dark but it is not so.” Other council members concurred. As Alpheus Cutler told the council in early May, “The only thing he wants is the word of Lord on the subject. . . . We have got a leader that can tell the mind of the Lord.”[19]

Following the example of Joseph Smith, Young encouraged robust debate and discussion among council members. According to Young, “Joseph declared for every man to spue [spew] out every thing there was in him, and see if there is not a foundation in him for a great work. . . . He wants to hear the brethrens views on the subject, and by talking over each others views, we learn each others feelings, and all learn what each other knows.” Certainly, Young stated, “There has always been an objection in this church to listening to what is term explateration [a slang term meaning to explain in detail], but if there are fools amongst us let them speak out their folly, and we will know who are men of wisdom.” Like Smith, Young also presided over the council through parliamentary procedure and the establishment of committees. According to Young, running the council both by revelation and candid debate meant that it was a “living body to enact laws for the government of this kingdom, we are a living constitution.”[20]

While Young encouraged vigorous discussions, his opinions and decisions—like those of Joseph Smith the previous year—held enormous sway. For instance, on March 22, after six weeks of discussions on a proposal to send missionaries to American Indian tribes, Orson Spencer motioned that Young make final decisions. Young initially “objected inasmuch as the responsibility rests upon the council.” In response, George Miller stated that the council had thoroughly discussed the matter and that he was “in favor of immediate action, and dont want to see the ship rot on the stocks.” Young then agreed to move forward as the final decision maker.[21] On other topics, council members likewise indicated that Young should make decisions following discussion.

One difference between the Joseph Smith era and the Brigham Young era was that under Young, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles became more important to the Council of Fifty. On April 11, Young stated, “Formerly one man stood at the head, now the Twelve stand there.” Over time, Young sometimes relied on prior discussions among the Twelve before meetings of the Council of Fifty to make decisions in the council. For instance, at the April 11, 1845, meeting, the Council of Fifty endorsed decisions regarding the Church’s publishing program and the Nauvoo print shop that had been made the previous day by the Quorum of the Twelve.[22]

Priorities of the Council under Young

Under Young’s direction, the Council of Fifty engaged less in the wide-ranging debates about earthly and heavenly constitutions that occupied it under Joseph Smith. Rather, the council focused on more practical matters, particularly how to govern the Saints in and around Nauvoo following the loss of the municipal charter, exploration of relationships with American Indian tribes, a search for a sanctuary in the American West, and the completion of the Nauvoo Temple. The shift from the philosophical to the pragmatic reflected Young’s own practical personality. In addition, the discussions under Smith had at least partially resolved many of the pressing theoretical concerns, such as the purpose of the council and the meaning of theocracy for the Latter-day Saints. Finally, the pragmatic turn under Young reflected the increasingly tenuous situation of the Latter-day Saints in Nauvoo: events demanded concrete decisions and a clear way forward for the Saints.

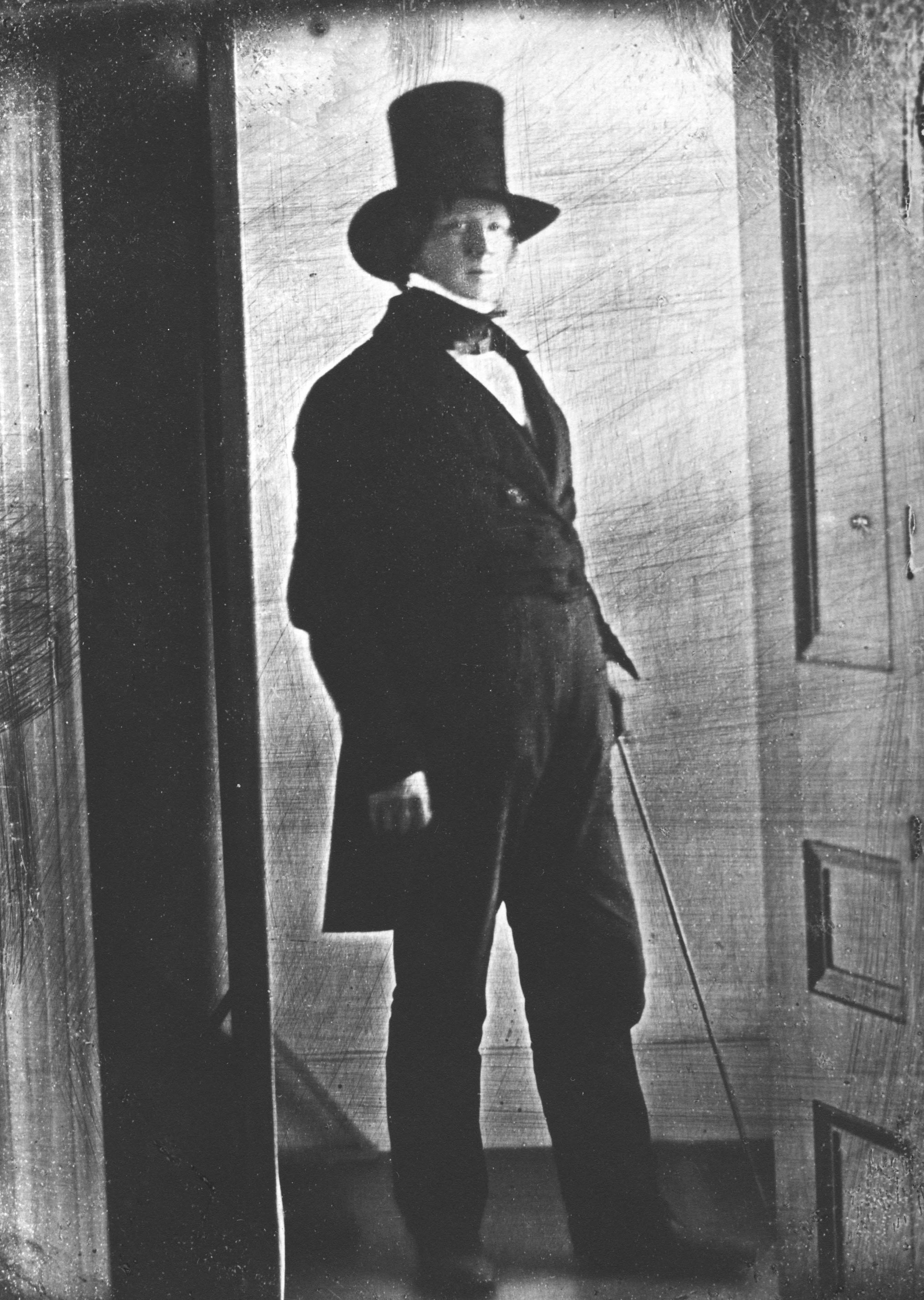

Brigham Young reorganized the Council of Fifty on February 4, 1845. Daguerreotype, circa 1846, attributed to Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Brigham Young reorganized the Council of Fifty on February 4, 1845. Daguerreotype, circa 1846, attributed to Lucian R. Foster. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

How to respond to the loss of the Nauvoo charter was of immediate concern when the council reconvened in February 1845. The Latter-day Saints had explicitly designed the charter to provide them with protections they had lacked in Missouri, including their own independent militia and municipal court with the unusual power of issuing writs of habeas corpus. The revocation of the charter—an indication that Illinois leaders believed the Mormons incapable of self-government—left the Mormons in Nauvoo without a city council, a court, a militia, a police force, and even the right to perform marriages. In the words of William Clayton, the revocation of the charter “laid us open to all the raviges of mobs & murderers.” Without the charter, the Saints felt especially vulnerable to internal dissidents, criminals who would prey upon the populace, and even the threat of a concerted outside attack by their enemies.[23]

Over the next several months, the Council of Fifty essentially became a shadow government in Nauvoo as it explored ways either to fight the repeal of the charter or to provide a semblance of government for the city. For instance, Young and other members of the council sent letters to leading lawyers asking for recommendations to seek legal and judicial remedies. They also wrote letters to the governors of each US state asking for their response to Mormon persecution and about the prospect of the Latter-day Saints settling elsewhere. Young, though, had little hope, telling the council that “the only object of our writing to the governors is to give them the privilege of sealing their own damnation.” On a more concrete level, the council helped establish an extralegal police force in the city—known as the “whistling and whittling brigades”—which relied on Church members to watch suspicious visitors to Nauvoo and, if necessary, intimidate them to leave the city. The council’s minutes indicate that the Saints were responding to real threats and that, when the vigilante justice threatened to get out of hand, Young tightened the controls on it.[24]

Even as council members discussed ways to govern and protect Nauvoo, they became increasingly focused on leaving the city. In 1844, the council had explored various possibilities for possible western settlements, focusing on California, Oregon, and Texas, all of which were then outside the borders of the United States. When council members learned that Texas had been annexed to the United States in March 1845, they no longer saw it as a viable option. Similarly, Oregon eventually dropped out of consideration, leading Young and other members of the council to increasingly focus on the Mexican territories that covered much of what is now the western United States. On March 1, Young instructed the council, “The time has come when we must seek out a location.” He connected the need for a sanctuary to the deteriorating situation for the Latter-day Saints in Illinois and the rest of the United States: “The yoke of the gentiles is broke, their doom is sealed, there is not the least fibre can possibly be discovered that binds us to the gentile world.”[25]

The early months of 1845 were dark days for Young and other Church leaders, as they contemplated the loss of the Nauvoo charter, feared the possibility that they would be driven from Illinois as they had from Missouri, and worried that Church leaders would be arrested on judicial writs from false charges, as they believed Joseph and Hyrum Smith had been the previous year. In response to his concerns, Young advocated that missionary work cease to the “Gentiles”—whom Young perceived as white Americans and Europeans—and focus rather on the house of Israel, including American Indians and others. Young also instructed at this time that the Relief Society not reconvene, as it had the previous two springs, apparently believing that some members had used the Relief Society to foment opposition against plural marriage and Joseph Smith.[26]

Young’s concern can also be seen in his increasingly harsh rhetoric within the Council of Fifty. Believing that “the gentiles” had rejected the gospel, persecuted the Latter-day Saints in Missouri and Illinois, and murdered Joseph and Hyrum Smith, he said that he did not “care about preaching to the gentiles any longer.” Paraphrasing Lyman Wight, he stated, “Let the damned scoundrels be killed, let them be swept off from the earth, and then we can go and be baptized for them, easier than we can convert them.” Furthermore, Young vowed that he would not allow himself to be taken by what he viewed as corrupt judicial officers with false writs.[27]

Young’s statements to the council regarding inflammatory speeches also give insight into his rhetoric. In March 1845, Young rebutted a comment that Almon Babbitt had made about Mormon rhetoric several years earlier in Missouri, a comment Young believed was targeted at Joseph Smith. “No man can ever speak against Joseph in my presence,” Young stated, “but I shall tell him of it.” Referencing those earlier speeches, which many believed had contributed to violence against the Saints, Young explained, “To the natural man this church has from the beginning had a boasting spirit but to the priesthood it does not appear so.” According to Young, “A man never could speak by the power of the spirit but his language would appear to this ungodly world as inflammatory.” Thus, Young partly attributed the inflammatory nature of some statements by himself and others as inspired by the Spirit. Nevertheless, a month later, Young also cautioned council members “to cease all kinds of harsh speeches which would cause the spirit of God to leave us. We want to lay aside all such things that we may enjoy peace in the city.”[28]

Under Young, the Council of Fifty focused on the need for the Saints to find a sanctuary in the West. Besides sending emissaries to American Indians, council members also studied the latest maps and reports and explorations. As new information came in, the council eliminated possibilities they considered impractical. Eventually the council began to focus on the Rocky Mountains and then the valley of the Great Salt Lake as the destination. Throughout this process, council members felt that they were being guided by revelation, but not until the time for departure neared did Young feel confident of the exact destination. On January 13, 1846, as the Saints were preparing to leave their homes in Nauvoo, Young declared, “The Saying of the Prophets would never be verified unless the House of the Lord should be reared in the Tops of the Mountains & the Proud Banner of liberty wave over the valley’s that are within the Mountains &c. I know where the spot is.”[29]

Young’s statement occurred when the Council of Fifty was meeting in the attic of the Nauvoo temple. Over the previous month, one of the council’s objectives had been realized: the completion of enough of the Nauvoo temple so the Latter-day Saints could perform temple rituals before they left for the West. A year earlier, in January 1845, Young had contemplated whether the Saints should remain in Nauvoo until the completion of the temple. He sought in prayer an answer and recorded the response: “we should.” On March 1, 1845, Young tied the completion of the temple with the exodus from Nauvoo: “It is for us to take care of ourselves and go and pick out a place where we can go and dwell in peace after we have finished the houses [the temple and the Nauvoo House] and got our endowment, not but that the Lord can give it to us in the wilderness, but I have no doubt we shall get it here.” On November 30, 1845, the construction was far enough along that Young partially dedicated the temple, and temple ordinance work—particularly endowments and marriage sealings—began on December 10. It was thus fitting that the final work of the Council of Fifty in Nauvoo involved final preparations for the exodus as the council met in the temple. Only when he was standing in the temple, as endowments and sealings occurred in nearby rooms, could Brigham Young announce with clarity the final destination of the Latter-day Saints’ exodus.[30]

Notes

[1] The language of this quotation has been standardized slightly for purposes of the title.

[2] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, March 11, 1844, April 18, 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 257, 40, 128 (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[3] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:222.

[4] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 10 and 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:32, 36, 43.

[5] Brigham Young, Journal, March 13, 1844, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[6] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 21, 1844, in JSP, CFM:59.

[7] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 5 and 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:82–84, 119–21.

[8] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 5 and 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:82, 119.

[9] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, in JSP, CFM:120–21.

[10] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, April 5, 1844, April 11, 1845, in JSP, CFM:119, 82, 128, 401.

[11] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 5, 1844, in JSP, CFM:84; Michael Hicks, “Minding Business: A Note on ‘The Mormon Creed,’” BYU Studies Quarterly 26, no. 4 (Fall 1986): 128; Brigham Young, Discourse, May 15, 1864, Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: F. D. Richards, 1855–86), 10:295.

[12] Leonard Arrington, American Moses (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 40.

[13] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 18, 1844, May 3, 1844, April 25, 1844, April 11, 1844, in JSP, CFM:110, 118, 138, 131, 101.

[14] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 6, 1844, in JSP, CFM:147–59; “Part 2: February–May 1845,” in JSP, CFM:205.

[15] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:218–25, 256.

[16] Young, Journal, February 4, 1845; Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:216, 225–27.

[17] Council of Fifty, Minutes, February 4, 1845, in JSP, CFM:226–27.

[18] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 6, 1845, in JSP, CFM:448.

[19] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, May 6, 1845, in JSP, CFM:257, 445.

[20] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1845, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:254, 401.

[21] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 22, 1845, in JSP, CFM:353–56.

[22] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1845, in JSP, CFM:390, 398.

[23] “Part 2: February–May 1845,” in JSP, CFM:212–15; William Clayton, Journal, December 27, 1844, quoted in JSP, CFM:213.

[24] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1845, March 18, 1845, in JSP, CFM:312, 330–31.

[25] “Volume Introduction,” in JSP, CFM:xlii; Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:257.

[26] Document 1.13, in Jill Mulvay Derr, Carol Cornwall Madsen, Kate Holbrook, and Matthew J. Grow, The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 168–71.

[27] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1845, March 18, 1845, April 15, 1845, in JSP, CFM:299–300, 337, 424–25.

[28] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1845, April 15, 1845, in JSP, CFM:307–9, 421–22.

[29] John D. Lee, Journal, January 13, 1846, 79.

[30] Council of Fifty, Minutes, January 13, 1846, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:257–58, 521; Young, Journal, January 24, 1845; “Part 4: January 1846,” in JSP, CFM:507.