American Indians and the Nauvoo-Era Council of Fifty

Jeffrey D. Mahas

Jeffrey D. Mahas, “American Indians and the Nauvoo-Era Council of Fifty,” in The Council of Fifty: What the Records Reveal about Mormon History, ed. Matthew J. Grow and R. Eric Smith (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 119-130.

Jeffrey D. Mahas coedited Council of Fifty, Minutes: March 1844 - January 1846 (2016). He is a documentary editor with the Joseph Smith Papers Project and is pursuing a PhD in history from the University of Utah.

“We’ll ask our cousin Lemuel, to join us heart & hand,

And spread abroad our curtains, throughout fair Zions land”

John Taylor, April 11, 1845[1]

Most scholarship on the Council of Fifty has focused on the political and religious aspirations of the council and its members. Questions of theodemocracy, Joseph Smith’s presidential campaign, or westward migration have dominated these discussions.[2] With the publication of the minutes of the council by the Joseph Smith Papers Project, it is clear that historians have underestimated the degree to which perceptions of and plans related to American Indians played into the Council of Fifty’s actions in Nauvoo.[3] Indeed, the council’s discussions during 1845 largely revolved around designs to establish alliances with and among the Indians living west of the Mississippi River. These discussions in the Council of Fifty reveal the central role Mormons assigned to Indians as they planned for their westward migration.

Mormon interest in American Indians originated with the Book of Mormon, which principally narrates the story of two civilizations: the Nephites and the Lamanites. According to Book of Mormon prophecies, the descendants of the Lamanites—identified by early Mormons as all Native Americans—would receive the Book of Mormon and convert en masse to the faith their forefathers had rejected. The Lamanites would then scourge all those who refused to repent “as a lion among the beasts of the forest, as a young lion among the flocks of sheep” before joining with the repentant Gentiles—the Mormon designation for white Euro-Americans—in building a New Jerusalem in North America.[4] Both the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith’s later revelations associated the mass conversion of the Lamanites and the subsequent conflict with the beginning of the Millennium.[5]

During the 1830s and early 1840s, Mormons made several attempts to bring about the conversion of the Lamanites, starting with the September 1830 commission directing Oliver Cowdery to “go unto the Lamanites & Preach my Gospel unto them & cause my Church to be established among them.”[6] During the 1830s, rumors of Mormon-Indian alliances among the Saints’ non-Mormon neighbors fueled anti-Mormon accusations and violence.[7] Within a few years, Church leaders encouraged members to downplay Mormon interest toward Indians.[8] The 1840s saw a return to proselytizing among American Indians, with men such as Jonathan Dunham, James Emmett, and John Lowe Butler being sent to the Stockbridge, Potawatomi, Sioux, and others groups in the Indian Territory west of the Missouri River or elsewhere. However, the purposes or expectations of these missions were shrouded in secrecy.[9] One of the great contributions of the Council of Fifty’s minutes is that they provide a more detailed explanation of early Mormon expectations for American Indians than previously existed, especially for 1844 and 1845.

The Council of Fifty under Joseph Smith

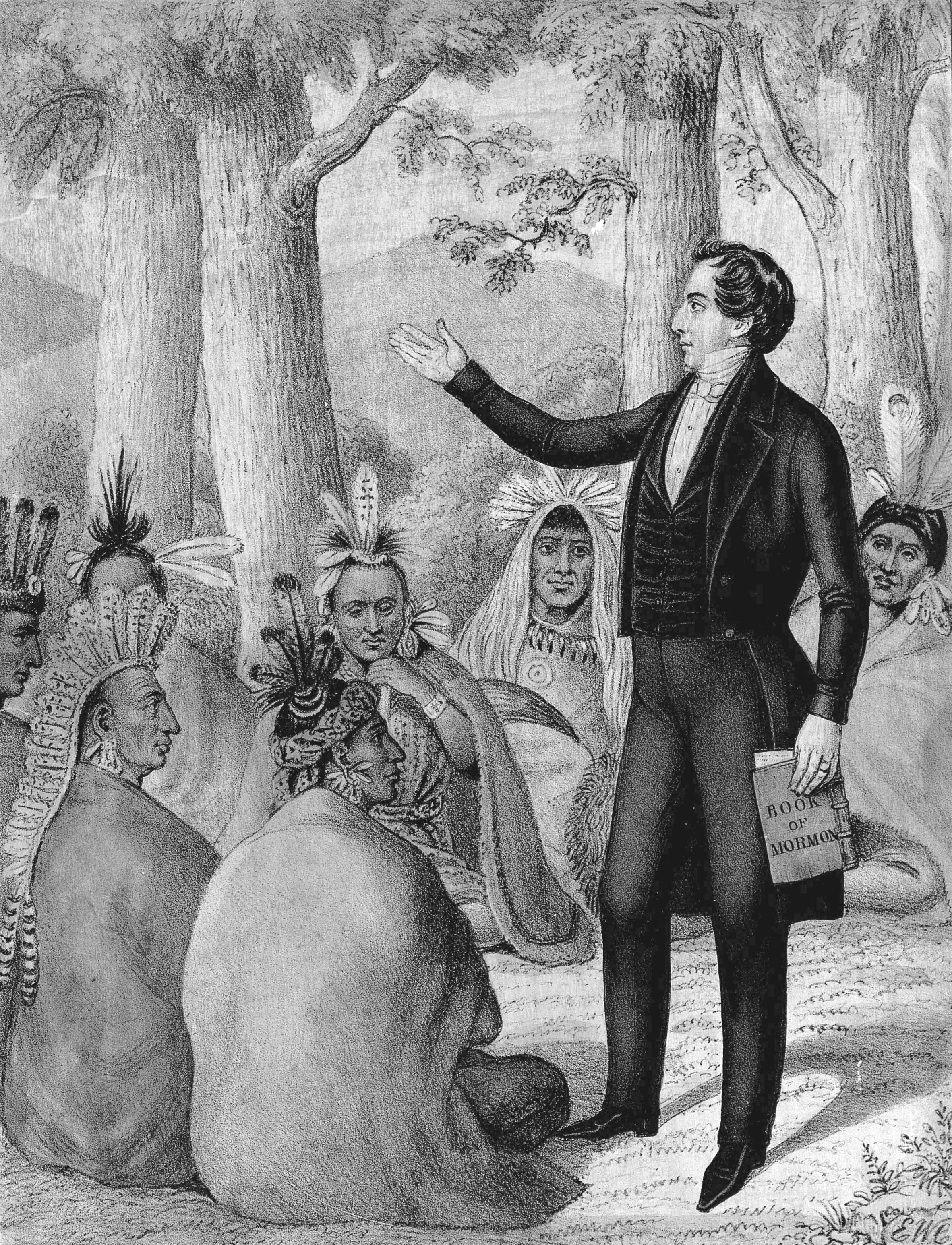

Joseph Smith conferred with a number of American Indian delegations in Nauvoo in the 1840s. Lithograph by Henry R. Robinson based on drawing probably by Edward W. Clay. Joseph the Prophet Addressing the Lamanites (New York City: Prophet, 1844). Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Joseph Smith conferred with a number of American Indian delegations in Nauvoo in the 1840s. Lithograph by Henry R. Robinson based on drawing probably by Edward W. Clay. Joseph the Prophet Addressing the Lamanites (New York City: Prophet, 1844). Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

Indians played a crucial role in the immediate impetus for the organization of the council. In 1843, apostle Lyman Wight and bishop George Miller led a large company of Saints to Black River Falls, Wisconsin Territory, to continue the Church’s lumber operations in the region.[10] During the following winter, these Saints had frequent contact with Winnebago, Chippewa, and Menominee Indians and sought permission to begin missionary work among these tribes.[11] Before they could follow through with their intentions, a hostile federal Indian agent in the area mistakenly claimed that the Mormons were trespassing on Menominee Indian lands, and local Mormon leaders began to worry that they would be forced from the area. Rather than return to Nauvoo, these men, led by Wight and Miller, wrote to Joseph Smith, proposing that the Wisconsin Saints abandon their logging efforts and instead create a Mormon colony in the Republic of Texas. They claimed with a great deal of exaggeration that the local Indians had received the Mormons “as their councilors both temporal and spiritual” and that they could convince these Indians to come with them to Texas. There they could create a settlement that would provide a foothold to spread the gospel to the native peoples in western North America as well as in Central and South America.[12]

When Joseph Smith received the letters on March 10, he assembled a small group of trusted Church leaders and advisers that would quickly become the Council of Fifty to discuss the Wisconsin Saints’ proposal. Despite the enthusiasm contained in these letters, American Indians were never the primary focus of the Council of Fifty under Smith’s leadership. Instead, the council focused much of its attention on the Wisconsin Saints’ proposal for a Mormon colony in the Republic of Texas.

On January 1, 1845, William Clayton, the council’s clerk, reflected on the council’s activities for the previous year and wrote that the council had “devised [a plan] to restore the Ancients [i.e., Indians] to the Knowledge of the truth and the restoration of Union and peace amongst ourselves.”[13] Nevertheless, under Joseph Smith, the council’s only explicit action in the minutes was to follow up on the Wisconsin Saints’ exaggerated reports by sending James Emmett “on a mission to the Lamanites [in Wisconsin] to instruct them to unite together,” presumably in preparation for their eventual mass conversion.[14] When Emmett conveyed his message to a Menominee leader, possibly Chief Oshkosh, the leader largely dismissed its practicality, and Emmett returned with nothing to show for his efforts.[15] Additionally, on April 4, the Council of Fifty met with a delegation of Potawatomi Indians in Nauvoo and Joseph Smith encouraged the visitors to “cease their wars with each other.”[16]

While the Council of Fifty spent little time in 1844 discussing or contemplating how Indians would fit into this new millenarian government, their attitudes changed after Joseph Smith was killed by an anti-Mormon lynch mob on June 27, 1844. In the Mormon worldview, Smith’s violent death was a literal and total rejection of the Mormons and their message by the nation. Smith’s death eroded whatever positive feelings remained for the United States among the Mormons. When the Illinois legislature repealed the statute providing a city government for Nauvoo in January 1845, it added to their outrage. Mormons interpreted these major disappointments within their millenarian worldview, associating their setbacks with the plight of Native peoples. Brigham Young publicly preached that the actions of Illinois and the United States had expelled the Mormons from political citizenship and made them “a distinct nation just as much as the Lamanites.”[17] Given this state of affairs, many Mormons now believed that the promised time had come for the American Indians to convert and “vex the Gentiles with a soar vexation.”[18]

The Council of Fifty under Brigham Young

With Mormons already interpreting recent setbacks within their millenarian framework, their worldview was seemingly confirmed with the unannounced and unexpected arrival in Nauvoo of Lewis Dana on January 27, 1845. Dana—a member of the Oneida nation—had been baptized along with his wife and daughter in the spring of 1840 after Dimick Huntington read them the entire Book of Mormon over the course of two or three weeks.[19] Several Mormons, including apostle Wilford Woodruff, interpreted Dana’s conversion as the beginning of the prophesied redemption of the Lamanites.[20] When Dana returned to Nauvoo in 1845, Latter-day Saints began again to discuss his place in the millennial Mormon–American Indian alliance. In February, Dana received a prophetic statement known as a patriarchal blessing that stated he would be “a Mighty instrument in kniting the hearts of the Lamanites together . . . bringing thousands to a knowledge of their Redeemer & to a knowledge of their Fathers.” The blessing explicitly connected Dana to the prophecies contained in the Book of Mormon, promising that he would “gather thousands of them [Lamanites] to the City of Zion.”[21]

A week after Dana’s arrival in Nauvoo, Brigham Young reconvened the Council of Fifty for the first time since Joseph Smith’s death. While the repeal of the city charter in January 1845 forced Church leaders to reconsider plans to find a new home, Dana’s arrival likely rekindled hopes that the other tasks charged to the council could be completed. Indeed, under Brigham Young the anticipated conversion of the American Indians took on a much more central role in the council’s deliberations. Throughout February, Church leaders informally discussed the possible role Dana would play in their designs. On March 1, 1845, the Council of Fifty began discussing Dana’s mission in earnest. At the beginning of the meeting, Young formally added Dana and nine other Mormons to the council—including Jonathan Dunham, a frequent missionary to the American Indians. When introducing Dana, Young told him that the council was organized not only “to find a place where we can dwell in peace and lift of the standard of liberty” but also “for the purpose of uniting the Lamanites, and sowing the seeds of the gospel among them. They will receive it en Masse.” As the “first of the Lamanites” to be “admitted to this kingdom,” Dana sensed his responsibility to bring about the long-anticipated mass conversion of his people and swore with uplifted hand, “In the name of the Lord I am willing to do all I can.”[22]

At this meeting of the Council of Fifty, Young announced his intentions to send eight men west with Dana to go from tribe to tribe seeking to forge a pan-Indian alliance. “I want to see the Lamanites come in by thousands and the time has come,” Young stated.[23] The certainty Young and other council members placed on an imminent Lamanite conversion reveals how thoroughly immersed they were in Mormonism’s millenarian theology. “Our time is short among the gentiles, and the judgment of God will soon come on them like [a] whirlwind” Young declared on March 11, 1845.[24] The council seemed to universally agree that in light of recent events they should halt Mormon missionary efforts among the Euro-Americans they viewed as Gentiles. Following the private deliberations of the Council of Fifty, Young publicly announced on March 16 that he would “scarcely send a man out to preach” that year, stating that “if the world wants preachers, let them come here.”[25] Young reiterated this policy a month later at the Church’s general conference, reasoning that just as the ancient apostles turned to the Gentiles when the Jews rejected the gospel, the latter-day apostles would preach only to Israelites because the Gentiles had rejected the gospel.[26] Apostle Heber C. Kimball took this resolve one step further and encouraged a total separation from the Gentile world. Contextually it is clear that the decision to not preach or interact with the Gentiles was directed solely toward white Americans and that Mormonism’s missionary impulse remained intact, in theory, on a global scale.[27]

The Western Mission

Nevertheless, the Mormons’ more global ambitions were put on hold in favor of the immediate mission to the American Indians. While the Council of Fifty was unanimous in believing that the time had come to send a delegation to the Native peoples in the West, there was less agreement over how the missionaries should proceed. For nearly two months following Brigham Young’s announcement of the mission, the body debated the missionaries’ destination and message. By March 18, Jonathan Dunham had received intelligence that eventually helped settle these debates. On that day, Dunham announced that he had learned of “a council of the delegates of all the Indians Nations” that would take place in southern Indian Territory in the summer of 1845.[28]

The Council of Fifty dispatched Phineas Young and other "western missionaries" to attempt to forge alliances with American Indian Tribes. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The Council of Fifty dispatched Phineas Young and other "western missionaries" to attempt to forge alliances with American Indian Tribes. Courtesy of Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

The council Dunham described had been called by the Creeks in response to violent altercations with both the Pawnee and the Comanche. According to James Logan, the federal Indian agent to the Creeks, the council was to be “an assemblage of deputations from all the Indian Tribes on this frontier as well as those of the wandering tribes of the distant Prairies to meet in Council on the Deep Fork on the first of May next, with a view of settling all difficulties that may exist between them respectively, and to discuss such matters as may tend to advance peaceable and amicable relations.”[29] Logan’s description of the scope of this council was no exaggeration. According to the Cherokee Advocate, by May 1845 nearly 850 delegates from eleven tribes had assembled at the Creek council ground.[30]

It is unclear how Dunham learned of this impending Indian council; however, the Council of Fifty immediately made attendance at this pan-Indian council a central goal of the “Western Mission.” Although Brigham Young had initially called for a party of eight or more, by April the council favored sending a smaller group of missionaries. On April 23, 1845, Lewis Dana and the men chosen to accompany him—Jonathan Dunham, Charles Shumway, and Phineas Young—left Nauvoo and began traveling southwest to the region surrounding Fort Leavenworth. There the missionaries tarried for ten days among the western Stockbridge and Kickapoo before continuing their journey south to the Indian council.[31] Both tribes had a history of favorable contact with Mormons, especially Dunham, and their interactions with the missionaries proved to be the only favorable results of the mission.[32] Unfortunately for the missionaries, their lengthy stay with the Stockbridge meant that the missionaries missed the conference they hoped to attend. Faced with this disappointment, Phineas Young and Charles Shumway abandoned the mission and returned to Nauvoo.[33] For his part, Phineas Young was disgusted with the whole affair and blamed the failures on Dana and Dunham’s incompetence.[34]

Meanwhile, Dunham and Dana remained west of the Missouri in Indian Territory and reverted to the original plan of going tribe to tribe. In August, Brigham Young sent out another small wave of missionaries to the Indians, but when they arrived near Fort Leavenworth they were met by Dana and another Mormon Indian, who brought news that Dunham had died in late July after an illness of three weeks.[35] When the council heard a report on the missionary efforts in September 1845, Young sought to put a positive spin on their labors, claiming that they had now “learned considerable of the feelings of the Indians towards us, and the prospect is good.”[36] Nevertheless, talk of an immediate Indian alliance disappeared from the council. While the missionaries had been gone, Church leaders had largely abandoned their more militaristic and millennial rhetoric surrounding a potential Mormon-Indian alliance. Under Brigham Young’s direction, a select group of Church leaders had formulated a new plan to send a company of Saints west, “somewhere near the Great Salt Lake.” In the fall and winter of 1845, the Council of Fifty primarily concerned itself with the practical preparations to move nearly fifteen thousand men, women, and children across the Rocky Mountains.[37]

Young optimistically looked to the West as the location for the promised redemption of the Lamanites to begin. Speaking of the Mormons’ contemplated home on the other side of the Rocky Mountains just a month before their departure from Nauvoo, Young reasoned that “it is a place where we could get access to all the tribes on the northern continent and some of the tribes could be easily won over. The shoshows [Shoshones] are a numerous tribe and just as quick as we could give them a pair of breeches and a blanket they would be our servants, and cultivate the earth for us the year round.”[38] Thus, the Mormon attempts to form an Indian alliance were deferred to await the removal of the Saints from Nauvoo and the colonization of the Great Basin.

Conclusion

Despite all the time and attention the Council of Fifty invested in bringing about the hoped-for conversion of and alliance with American Indians, they had had little or no success by the time wagons began crossing the Mississippi River in February 1846. Nevertheless, for historians interested in Mormon-Indian relations, the records of the council’s deliberations provide an unprecedented window into Mormon expectations during the tumultuous years of 1844 to 1846. However, the value of the Council of Fifty minutes is not limited to the chronological scope of the minutes. Instead, the debates and discussions surrounding Mormon conceptions of and designs for American Indians illuminate earlier secretive attitudes and beliefs and also provide greater context for understanding the relationship between Mormon settlers and their Indian neighbors in the Great Basin through the nineteenth century and beyond.

Notes

[1] From Taylor’s lyrics to the song “The Upper California,” in Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 11, 1845, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844–January 1846, vol. 1 of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 402 (hereafter JSP, CFM).

[2] See, for example, Klaus J. Hansen, Quest for Empire: The Political Kingdom of God and the Council of Fifty in Mormon History (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1967); D. Michael Quinn, “The Council of Fifty and Its Members, 1844–1945,” BYU Studies 20, no. 2 (Winter 1980): 163–97; Andrew F. Ehat, “‘It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth’: Joseph Smith and the Constitution of the Kingdom of God,” BYU Studies 20, no. 3 (Spring 1980): 253–80; and Jedediah S. Rogers, ed., The Council of Fifty: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2014).

[3] A slight exception may be scholarship focusing on Mormon splinter groups—such as the one led by Alpheus Cutler, who later placed a great deal of emphasis on Indian missions. See, for example, Danny L. Jorgensen, “Building the Kingdom of God: Alpheus Cutler and the Second Mormon Mission to the Indians, 1846–1853,” Kansas History 15, no. 3 (Autumn 1992): 192–209.

[4] 3 Nephi 21:12; Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (New York: Knopf, 2005), 84–108; W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 57–58; Armand L. Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Urbana: University of Illinois, 2003), 48–52.

[5] Revelation, December 25, 1832 [D&C 87], in Matthew C. Godfrey, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 2: July 1831–January 1833, vol. 2 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 330–31 (hereafter JSP, D2); Revelation, December 16–17, 1833 [D&C 101], in Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Brent M. Rogers, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 3: February 1833–March 1834, vol. 3 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2014), 396.

[6] Revelation, September 1830–B [D&C 28], in Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, Grant Underwood, Robert J. Woodford, and William G. Hartley, eds., Documents, Volume 1: July 1828–June 1831, vol. 1 of the Documents series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, Richard Lyman Bushman, and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2013), 185.

[7] Reeve, Religion of a Different Color, 52–105.

[8] Joseph Smith to William W. Phelps, July 31, 1832, in JSP, D2:266.

[9] Ronald W. Walker, “Seeking the ‘Remnant’: The Native American during the Joseph Smith Period,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (1993): 1–33.

[10] George Miller to “Dear Brother,” June 27, 1855, Northern Islander, August 23, 1855, [1].

[11] See for example Joseph Smith, Journal, February 20, 1844, in Andrew H. Hedges, Alex D. Smith, and Brent M. Rogers, eds., Journals, Volume 3: May 1843–June 1844, vol. 3 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, ed. Ronald K. Esplin and Matthew J. Grow (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2015), 179.

[12] Lyman Wight et al. to Joseph Smith et al., February 15, 1844; George Miller et al. to Joseph Smith et al., February 15, 1844, in JSP, CFM:17–39.

[13] William Clayton, Journal, January 1, 1845, quoted in Ehat, “‘It Seems Like Heaven Began on Earth,’” 268.

[14] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 21, 1844, in JSP, CFM:58.

[15] Council of Fifty, Minutes, May 31, 1844, in JSP, CFM:171.

[16] Council of Fifty, Minutes, April 4, 1844, in JSP, CFM:75–76.

[17] William Clayton, Journal, February 26, 1845, quoted in James B. Allen, No Toil nor Labor Fear: The Story of William Clayton, Biographies in Latter-day Saint History (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2002), 174.

[18] Revelation, December 25, 1832 [D&C 87], in JSP, D2:330.

[19] Oliver B. Huntington, History, 1845–46, 83, Oliver Boardman Huntington, Papers, 1843–1932, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[20] Wilford Woodruff, Journal, July 13, 1840, in Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833–1898, ed. Scott G. Kenney, vol. 1, 1833–1840 (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1983), 483.

[21] Patriarchal Blessing, John Smith to Lewis Dana, ca. 1845, Patriarchal Blessing Collection, Church History Library, Salt Lake City (hereafter CHL).

[22] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:255.

[23] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1, 1845, in JSP, CFM:257.

[24] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 11, 1845, in JSP, CFM:299.

[25] Minutes, March 16, 1845, Historian’s Office, General Church Minutes, 1839–1877, CHL.

[26] “The Conference,” Nauvoo Neighbor, April 16, 1845, [2].

[27] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 22, 1845, in JSP, CFM:356.

[28] Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 18, 1845, in JSP, CFM:342.

[29] James Logan to T. Hartley Crawford, March 3, 1845, in US Bureau of Indian Affairs, Letters Received by the Office of Indian Affairs, 1824–81, National Archives Microfilm Publications, microcopy M234 (Washington, DC: National Archives, 1959), reel 227.

[30] “The Indian Council,” Cherokee Advocate, May 22, 1845, [4].

[31] Phineas Young, Journal, April 23–May 19, 1845, CHL.

[32] Walker, “Seeking the ‘Remnant,’” 18, 24.

[33] Jonathan Dunham to Brigham Young, May 31, 1845, Brigham Young Office Files, CHL.

[34] Phineas Young, Journal, May 19, 1845, CHL.

[35] Daniel Spencer, Journal, August 3–18, 1845, CHL.

[36] Council of Fifty, Minutes, September 9, 1845, in JSP, CFM:471.

[37] Council of Fifty, Minutes, September 9, 1845, in JSP, CFM:472.

[38] Council of Fifty, Minutes, January 11, 1846, in JSP, CFM:518.