From Council Bluffs to the Salt Lake Valley—1852

The Call of Zion: the Story of the First Welsh Mormon Emigrants, ed. Ronald D. Dennis (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1987), 69-77.

Life for the 113 Welsh converts in Council Bluffs and for several others who had remained at St. Louis offered numerous difficulties and challenges. Most had not gone ahead with the George A. Smith Company and their compatriots simply because their resources were exhausted by the time they completed the Atlantic crossing and the ascension of the two rivers. A few who may have had the wherewithal to continue on to the Valley that same year had been requested to stay behind and preside over the other Buena Vista and Hartley emigrants.

With an organized body of Welsh Saints in Council Bluffs, future immigrants of the same language would have a warm welcome, in addition to instruction and guidance as to how they could complete their journey to the Valley. Housing would be provided, employment information would be given, and assistance in getting “fitouts” would be available.

William Morgan was selected to preside over the Welsh branch of the Church in Council Bluffs. Morgan wrote several letters to the brethren in Wales to give them the benefit of his experience and to encourage all the Saints in the old country to begin preparations immediately for emigration. He also sent them copies of the Frontier Guardian, the newspaper published by the Mormons in Council Bluffs. In return, Morgan was to receive an ample supply of Udgorn Seion, the periodical which succeeded Prophwyd y Jubili and which contained new of Mormons in Wales.

Morgan was a liberal dispenser of counsel and advice as to how to make the sea voyage more enjoyable than the one he had had. In a letter dated 25 December 1849, he wrote to President Phillips: “We advise everyone who will be emigrating to take care that their boxes are strong, made of dry wood; some have suffered losses because their boxes were not dry, and so their clothes have become mouldy. Potatoes on the ocean would be very desirable, and herrings, oat flour, bacon, dried beef, pepper, mustard, salt, pickles, onions, and oranges” (Udgorn Seion, February 1850, 52, TD15).

He also recommended they bring some brandy, as it was “beneficial to warm the stomach” when the weather was cold and when the sea was rough.

Many gold diggers headed for California were expected to pass through Council Bluffs in the spring of 1850. Some of the saints had made considerable profit by selling provisions to them; Morgan saw no reason why the next company of Welsh should not take advantage of such an opportunity as well, and he promised to send further information as to what items the emigrant should purchase in Britain for selling in America. [1]

Morgan reported performing two marriages among the Welsh by the end of 1849: Mary Jones to John Williams, and Alice Richards to Edward Evans. Alexander Owens had died from yellow fever; William Phillips was to inform Owens’s wife in Twynrodyn (a suburb of Merthyr Tydfil). Cholera, according to Morgan, was no longer a problem in St. Louis and had not reached Council Bluffs. [2]

Some were able to obtain jobs in the Council Bluffs area. Others were forced to travel all the way back to St. Louis to find work. In October 1849 John Hughes Williams, Rees Price, Morgan Hughes, Noah Jones and William Lewis [3] all returned to St. Louis in hopes of getting employment in the coal diggings at Gravois, a place in the vicinity of St. Louis. There they met David D. Bowen and Morgan David, who had stopped off at St. Louis back in April because of the illnesses of their wives and children.

Bowen, a widower by this time, was informed by Rees Price of one Phoebe Evans in Council Bluffs, a seventeen-year-old Welsh girl whom Bowen should consider marrying. The following spring Bowen took Price’s advice and traveled to the “Bluffs” where he courted and then wed young Phoebe Evans. Their return to St. Louis resulted in a very cool reception on the part of Morgan Hughes, Phoebe’s brother-in-law, because Bowen had not obtained his permission for the marriage. And Morgan David’s daughters, sister-in-law to Bowen, were bitter toward Phoebe, possibly because they (at least two of them) were just as old and just as eligible as she.

During the next two years, Bowen worked and saved towards making the overland journey to the Salt Lake Valley. At times he earned as much as twenty-five dollars per week; at times the amount was far less. And on two occasions for periods of several weeks he was totally incapacitated by illness and had no income at all. Others of his fellow Welsh Saints were faced with similar circumstances.

By June of 1852 most of the remaining Buena Vista and Hartley immigrants were fitted out and ready to begin their journey to the Rocky Mountains. Disease, misfortune, and defection had reduced their numbers. In the winter of 1850 there had been much illness among the Saints at Council Bluffs. William Treharne was among the fatalities. [4] Noah Jones, the poet, died of Bright’s disease in the fall of 1851. His dying wish was that his orphaned fourteen-year-old daughter, Mary, be allowed to cross the plains with the Welsh Saints the following year. In 1852 the explosion of the steamer Saluda killed William Rowland and two of his children.

During the three years which William Morgan and his fellow Welsh converts remained at Council Bluffs, they were joined by other Welsh Mormons form various parts of Wales. Those who could afford to continue immediately to the Valley did so; most, however, stayed in Council Bluffs until 1852 when the bulk of the remaining Welsh Saints traversed the plains together.

There were nine wagons of Mormons who traveled from Gravois to Council Bluffs to join with the others for the crossing. Among these was David D. Bowen, who had made enough money by January 1852 to purchase two yoke of oxen and a wagon “on shares” with Thomas Vargo for the purpose of going to the Salt Lake Valley. This small band met together at St. Louis on 6 April 1852 and began their journey across the State of Missouri and up to Council Bluffs. They stayed together as far as Lexington, where Bowen and Vargo struck out on their own with their “shared” wagon. At St. Joseph a misunderstanding occurred between the two, and they decided to part company. Each received one yoke of oxen, a cow, and half a wagon. Bowen sold his share of the wagon to Vargo, put his wife and child on a steamer from St. Louis, and proceeded to finish the remainder of the journey on foot with his three animals. Once he reached Council Bluffs in mid-May he made an agreement with an older gentleman by the name of Daniel Shearer. Bowen agreed to haul him and his luggage to Salt Lake City in exchange for the wagon which Shearer owned. Then Bowen worked at unloading steamboats and hauling wood until the main body was prepared to depart about one month later.

By 21 June the Welsh had gathered near Winter Quarters, where they were visited by Apostle Ezra T. Benson. They needed an interpreter to translate Benson’s instructions as to how they were to be organized for the crossing. William Morgan was appointed Captain of Fifty (the Welsh with a few English and French made up fifty wagons). His counselors were William Davis and Rees Jones Williams, Davis’s son-in-law. Three days later they crossed the Missouri and camped at Winter Quarters for another three days.

On the morning of 28 June, as the company finally got under way, Bowen lamented: “I had a deal of trouble with my cattle for they was not broken, by very whiled [wild] and young. The day we started from winter quarters was very hot. I leboured so hard with the cattle and sweat so much that I had the headache that bad I was all most blind all day” (28 June 1852). In the afternoon William Davis showed his lack of experience at driving a team by running his wagon into another one and breaking his axletree. There was a delay until the following day while repairs were made.

Morgan reported that five buffaloes were killed during the crossing; he described the taste as similar to Welsh beef. It was his custom to ride ahead of the camp to determine the trail and places suitable for stopping.

On one occasion Morgan found himself in the midst of several hundred Sioux and was greeted by one who appeared to be a chief: “ ‘How do, Mormon good.’ ” Morgan was then taken to the Indian camp about a mile-and-a-half away, where he was invited to sit down and smoke a “pipe of peace” with the chiefs. Morgan compared this unique custom to the handing around of the shilling jug in the taverns of Wales for each to take a drink (Udgorn Seion, 27 August 1853, 145, TD30).

On the whole, the journey for the 1852 Welsh pioneers was considerably was considerably more pleasant than it had been for those who crossed in 1849. At the outset William Morgan reported cheerily in a letter dated 22 June 1852: “All the Saints are in good health, each one with his canvas tent as white as snow. . . . Much milk in our camp is thrown out as casually as is the bathwater used by three or four Merthyr colliers we have more than we can use, and there is no one close by in need of it” (Udgorn Seion, 7 August 1852, 259–60, TD28). On 20 September 1852, near the end of the journey, Morgan wrote that the weather had been “unusually moderate” (Udgorn Seion, 8 January 1853, 32, TD29). They had experienced no rainstorms and no snow, even when they went through the mountain pass which had buried the 1849 pioneers in snow. Four Welshmen, however, died before they reached the Valley. One of these was the nine-year-old son of the widow Martha Howells. Morgan describes the happening:

We administered to him through the ordinances of the Church of Jesus Christ, according to the scriptures, and the next night he was strolling around the camp. He fell sick again in a day or two, and Bro. Taylor and myself administered to him again, but he died in spite of everything and everyone. (Udgorn Seion, 8 January 1853, 32, TD29)

When the company reached Fort Laramie, they crossed to the south side of the Platte River. The unusually high water of the river made crossing difficult, and many things were lost as a consequence. A few days later they arrived at Deer Creek, where they stayed for several days. Here David D. Bowen had difficulty with Brother Shearer:

Here I had a quarrell with old Sherar in consequence of his wagon which he promise me for hauling him and his luggage to Salt Lake City. He said that he did not calculate to give me the wagon. We had to get other men to settle between us. He promised again to give me the wagon or I was going to leave him and his wagon there. I listen to his fair promises and haul him along again. (29 September 1852, 30)

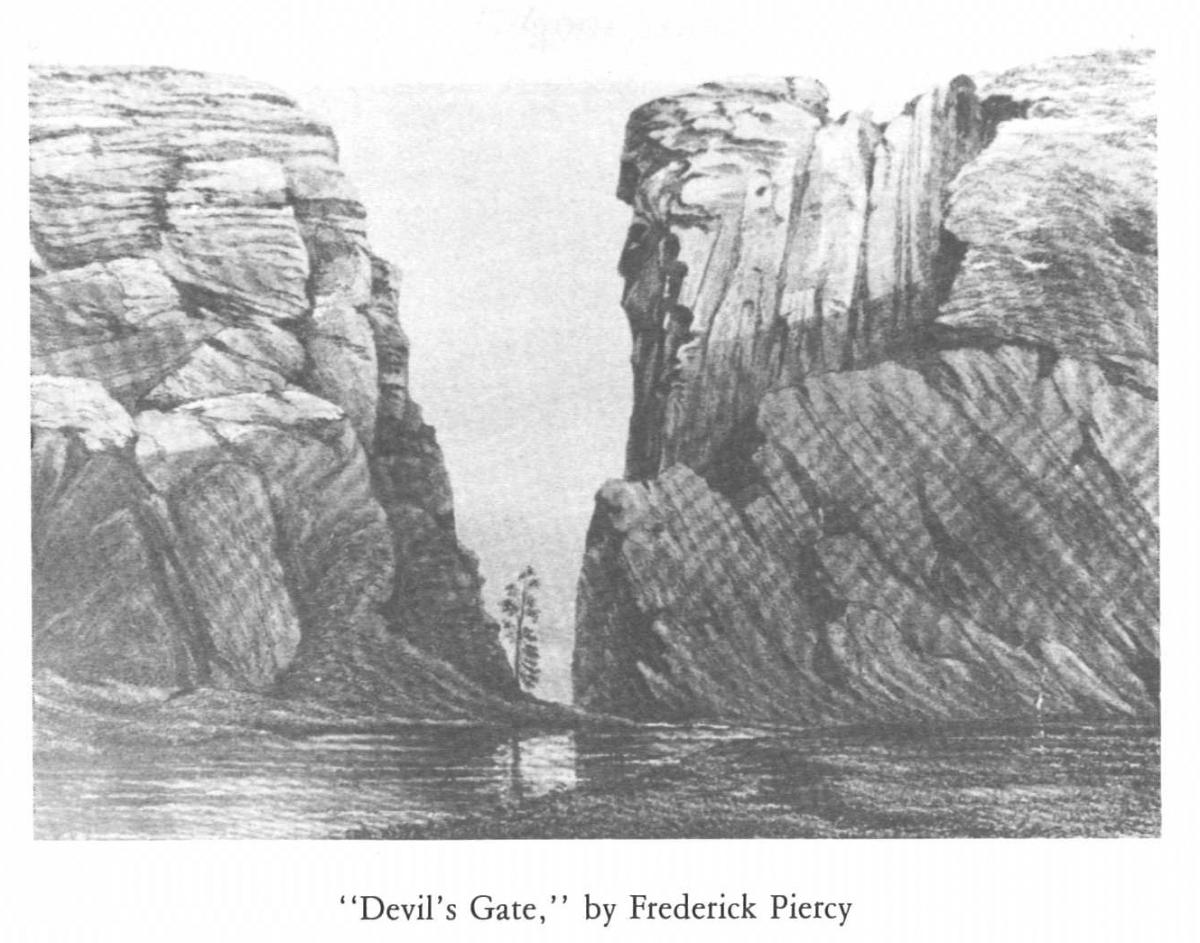

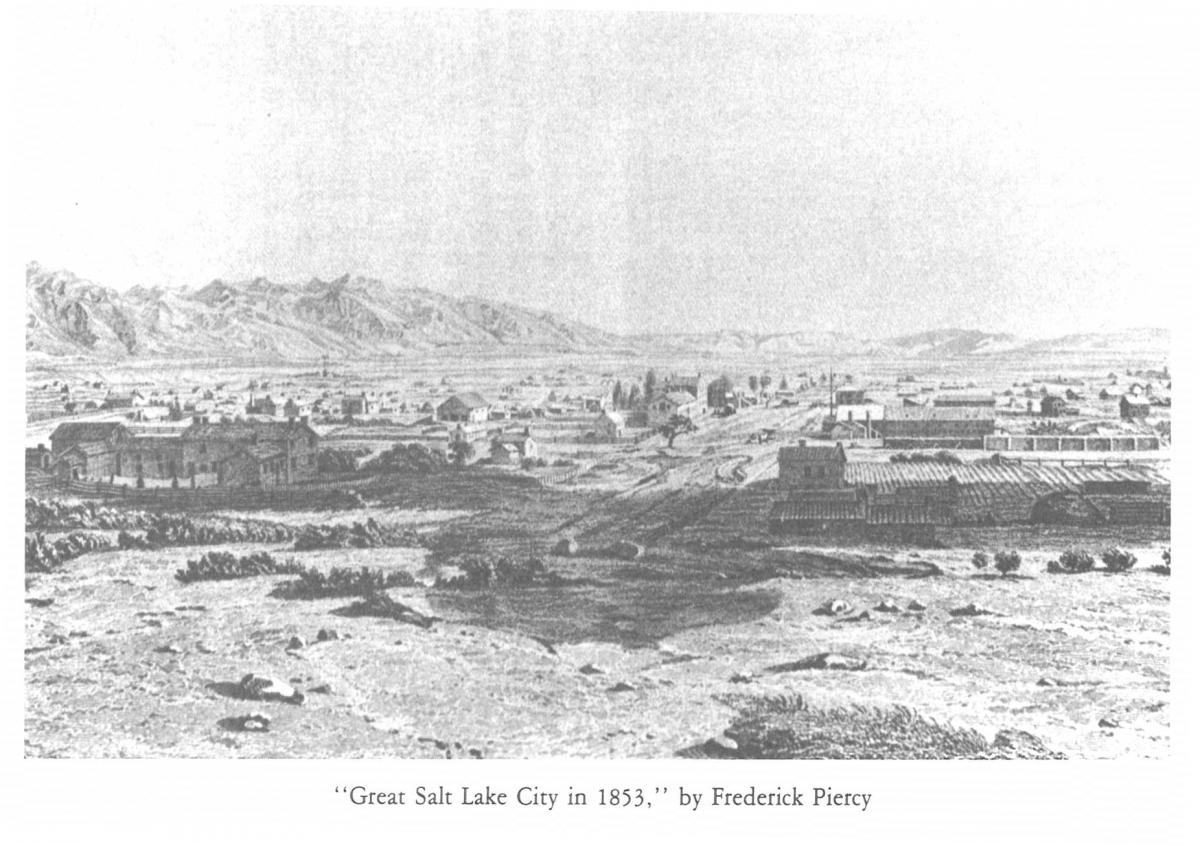

A number of cattle died at Devil’s Gate a short time later. It was there the company divided into several parties. David D. Bowen’s “Ten” traveled alone the rest of the way to the Valley. On 23 September, they reached the mouth of Emigration Canyon, where they were visited by Bishop Lorenzo D. Young, Brigham Young’s brother. His main message, according to Bowen, was to “mind Number One,” the first principle in the Valley. Two days later they went down into Salt Lake City, the valley. Two days later they went down into Salt Lake City, arriving in the early afternoon. Bowen’s wagon partner once again decided that he would not part with his wagon. Bishop Joseph D. Noble, asked to arbitrate in the matter, decided that Bowen and Shearer should each have half, but Shearer was unwilling to sell his half or to buy Bowen’s half. Finally Bowen sold his half to a man from San Peter in exchange for twenty dollars in lumber.

When the main body of the Welsh was about eight miles from the Salt Lake Valley, they had a reunion with their beloved Captain Jones. Jones, together with Thomas Jeremy and Daniel Daniels, had been called by Brigham Young to return to Wales on another mission. More than three years had elapsed since the 1849 group had left Council Bluffs, and emotions were strong as the 1852 group welcomed Jones into their midst. Morgan described the reunion in a letter dated 20 September 1852: “After shaking hands, embracing, weeping and kissing, we went to the bank of the river where he [Dan Jones] had left his horse, having traveled from twenty to thirty miles during the night ahead a day in his friendship, to converse with each other about things pertaining to the kingdom of our God. Oh, brethren, how sweet the words poured over his lips” (Udgorn Seion, 8 January 1853, 33, TD29).

Later in the day, Thomas Jeremy and Daniel Daniels arrived at the Welsh gathering and drank deeply from old friendships as they joined in the camaraderie. Jones gave Morgan a letter which he was to present to Bishop Edward Hunter just as soon as he arrived with his company in the Valley. Morgan was so moved by the letter that he quoted a segment of it in his own letter dated 25 June 1853 to Phillips and Davis back in Wales:

“Esteemed Bishop Hunter,—Many of my compatriots are coming across in the 13th Company; I do not known their condition; perhaps their money and their provisions are scarce. If so, when they reach the Valley, I shall be grateful to you for furnishing them their needs, through the hand of Brother Morgans [sic], and I shall pay you in Manti, San Pete Valley.” (Udgorn Seion, 27 August 1853, 147, TD30)

A few days later several other Welsh brethren arrived in the camp. These had traveled over thirty miles from Salt Lake City with a load of “watermelons, mushmelons, potatoes, pickle cucumbers, grapes, etc.” These delicacies came as a welcome treat to those who had spent three months on the trail. Two days later, just before the camp reached Little Mountain, they found “a multitude of the brethren” (Morgan, Udgorn Seion, 27 August 1853, 144, TD30) awaiting them with wagons of fruit and vegetables from the valley. Among the group were John Parry, Caleb Parry, Daniel Leigh, Owen Roberts, and Cadwalader Owens. Delighted at having their ranks swelled with the newcomers, these 1849 pioneers extended a sincere and loving welcome to their compatriots.

Morgan was pleased at how the crossing had gone: “Although the journey was long, I considered it nothing but enjoyment every step of the way” (Udgorn Seion, 27 August 1853, 146, TD30). He gave equally positive comments concerning everything and everyone in the Valley and predicted that the Salt Lake Temple would be completed three years hence. [5]

Conclusion

Several thousand more Welsh Saints journeyed to the Salt Lake Valley during the next decade. They usually came in clusters rather than in companies, with the 560 “sons of Gomer” on board the Samuel Curling in 1856 constituting a notable exception. Many of them settled in the same geographical area—Malad, a city in southern Idaho, and Spanish Fork, a city fifty-five miles south of Salt Lake City, were initially Welsh communities. The first and second generation Cambrians were conscientious in the preservation of the language and in the observance of periodic Welsh celebrations. By the turn of the century there were many Joneses, Davises, and Williamses who spoke with great pride of their Welsh ancestry. They had to do so, however, in English.

Notes

[1] No letter containing such information every appeared in the Udgorn Seion.

[2] While the Welsh Saints were being decimated by the cholera along the Mississippi and Missouri river in mid-1849, the same disease had reached epidemic proportions in the Merthyr-Tydfil area. One of its victims was the reverend W. R. Davies, the person who had coined the epithet Latter-day “Satanists.”

[3] There were three men by the name of William Lewis among the emigrants. The one who stayed in Council Bluffs instead of continuing directly on to Utah was number 70 on the Buena Vista passenger list.

[4] His daughter Jane had also been sick for several days when she heard of her father’s death. She was administered to by Brother Abel Evans, whereupon she arose immediately and rode six miles on horseback to attend her father’s funeral (see Ashton, 79).

[5] The actual completion of the Salt Lake Temple was not until nearly four decades later.