A Year of Decision: 1847

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 81–104.

The year 1846 has been called “the year of decision” because of its key place in American history. [1] The following year, 1847, played a similarly pivotal role in Latter-day Saint history.

During 1847, three major groups of Latter-day Saints were involved in building the American West: (1) The main body of the Church was at Winter Quarters on the Missouri River. In the spring, Brigham Young led the first party from this group toward the Rocky Mountains; (2) The Mormon Battalion completed its march to California and made significant contributions to several communities there; and (3) The Brooklyn colony was developing its settlement on the San Francisco Bay.

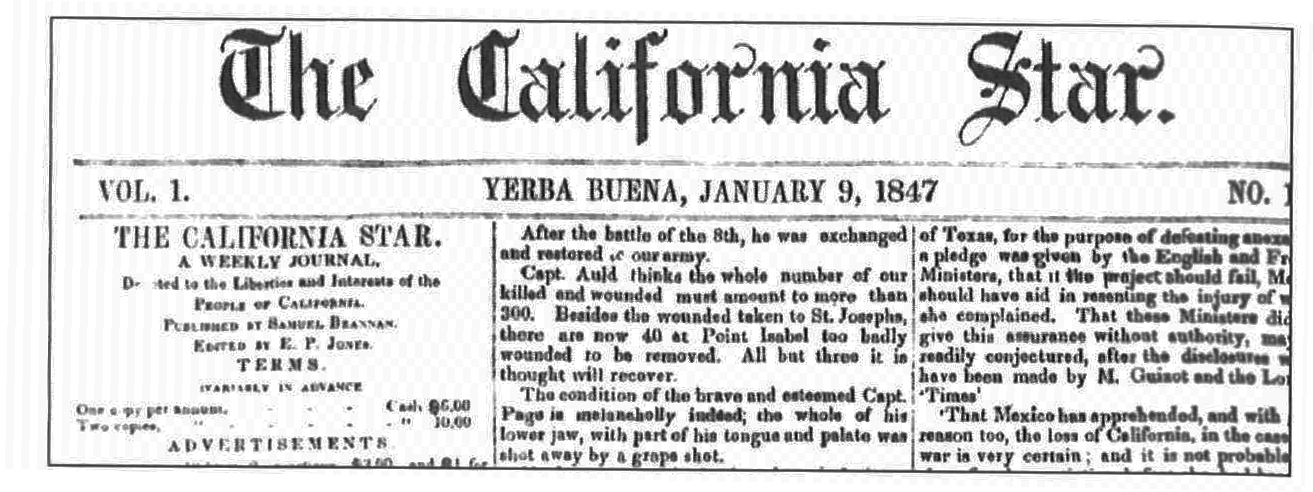

In Yerba Buena, Samuel Brannan began the year on 1 January by issuing another extra in advance of his regular publication of the California Star. He announced: “We shall commence publishing a paper next week, which will be the government organ by the sanction of Colonel Freemont, who is now our Governor.” [2]

Brannan sent a copy of the extra, together with a circular, to the Church newspaper in Great Britain, the Millennial Star.He reported: “In relation to the country and climate we have not been disappointed . . . but, like all other new countries, we found the accounts of it very much exaggerated.” [3]

On 9 January 1847, Brannan began weekly publication of the California Star. The newspaper was California’s second and began publication just five months after Monterey’s Californian, which in May was moved to San Francisco where it competed directly with the Star. In contrast to the Prophet and the Messenger, which Brannan had published in New York, this paper “was not issued as an organ of Mormonism,” but rather as a general newspaper. [4] Although Samuel Brannan was the paper’s proprietor, by April Edward Kemble, the non-Latterday Saint who had acted as Brannan’s assistant in New York and who had come with the group on the Brooklyn, assumed the editorship.

The California Star

The California Star

The Donner Tragedy

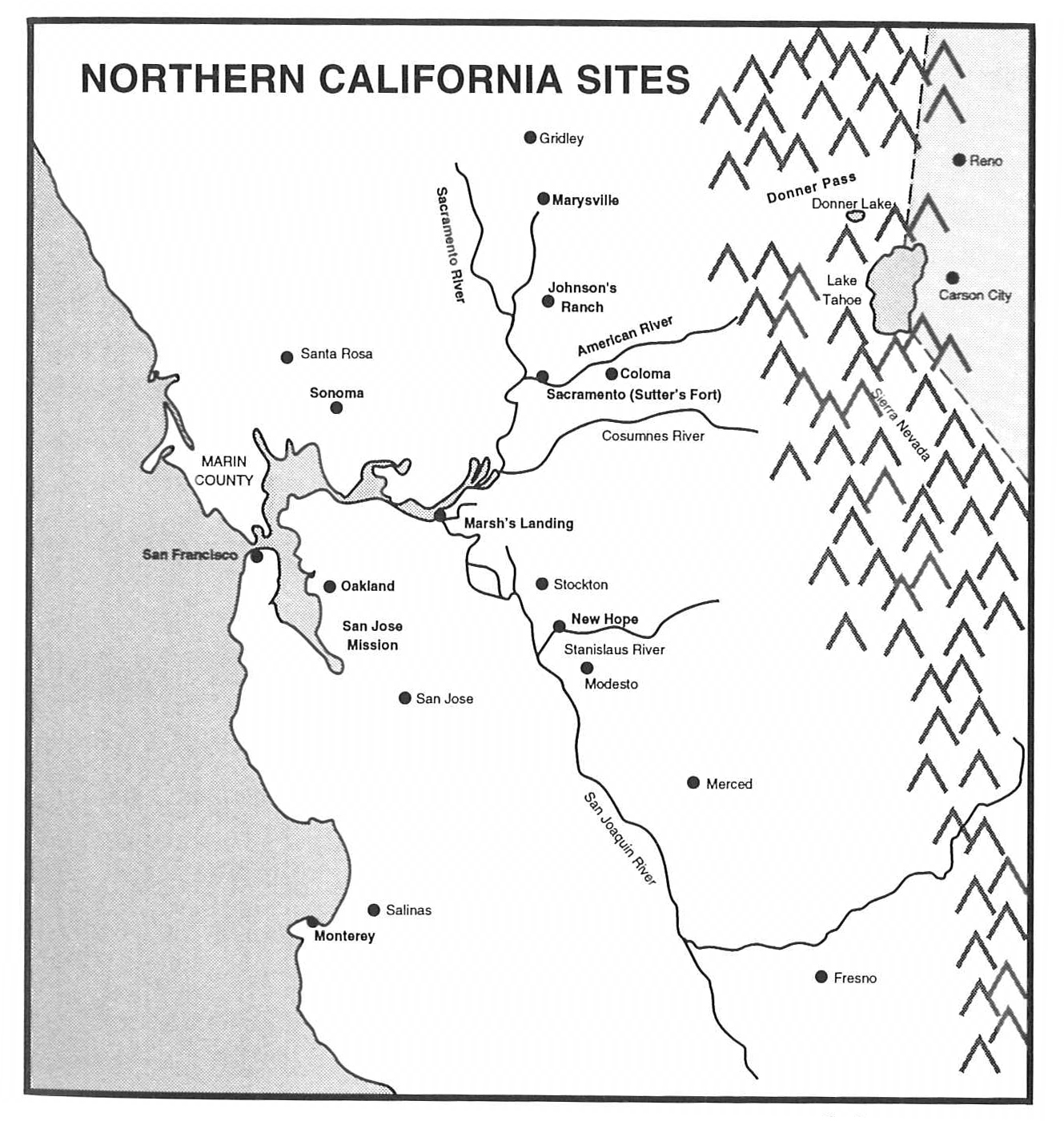

The 1846–47 winter was early and violent. It trapped the Donner wagon train of sixty immigrants in the Sierra Nevada mountains without adequate provisions. By mid-January a few of the party had snowshoed out of the mountains to Johnson’s Ranch, near present-day Marysville. Winter rains had flooded the Bear River and rendered the Sacramento plains a vast quagmire. Nevertheless, there was no time to waste. John Rhoads, a Latter-day Saint whose family had arrived overland just three weeks earlier, volunteered to go to Sutter’s Fort for help. Lashing two pine logs together with rawhide and forming them into a raft, he crossed the Bear River. Taking his shoes in his hands and rolling his pants up above his knees, he waded through water that was frequently three feet deep. Sometime during the night he reached the fort although the journey generally took about two days. [5] Volunteers were scarce because the war with Mexico had brought about a shortage of men. With some difficulty, a group of twenty was recruited and dispatched from Sutter’s Fort. After several attempts hindered by defections, only seven rescuers remained, including John Rhoads and his brother Daniel. To reach the summit, they had to break a trail through soft, waist-deep snow.

They finally reached the Donner Party camp on 18 February. “They saw only snow, and a sudden fear fell upon them that they had struggled so hard only to arrive too late. Spontaneously, they hallooed together. At the sound they saw a woman emerge, like some kind of animal, from a hole in the snow. They floundered toward her, and she, tottering weakly, came toward them. She spoke, crying out in a hollow voice, unnerved and agitated: ‘Are you men from California, or do you come from heaven?’” [6]

The rescue party was not large enough to take all the survivors out. They had to make the painful choice of who would go and who would stay. John Rhoads remembered his promise to Harriet Pike, one of those who had walked out to Johnson’s Ranch and a daughter of the Latter-day Saint laundress, Lavinia Murphy. He had promised that he would bring her babies out if he had to tie them on his back. Upon searching the camp, Rhoads found that Mrs. Murphy and her seventeen-year-old son had just died. John quickly rolled the one surviving Pike child, Naomi, in a blanket and hastened up the snow ramp to overtake the rescue party with its twenty-two immigrants. He carried her in the blanket, even after horses were obtained, as the child was too emaciated and frail to ride alone. Surprisingly, she lived to be ninety-three years old. She was one of the last Donner survivors when she died.

Meanwhile, word of the Donners’ plight reached Yerba Buena. Samuel Brannan published the story in his paper and expressed hope that the community would do something to help the immigrants. [7] Under the leadership of Washington A. Bartlett, supplies were gathered and a new rescue party of twenty men, including Brooklyn passenger Howard Oakley, was dispatched four days later.

By early March, lingering snow had caused most of the rescue party to give up. Oakley was one of only seven who continued through the deep snow over the pass. The group found eleven survivors huddled around a fire which had melted a big hole in the snow. Oakley received the assignment to bring out seven-year-old Mary Donner. [8]

Samuel Brannan’s Challenges

The Latter-day Saints in California had their own problems. In his New Year’s Day circular, Samuel Brannan lamented that “about twenty males of our feeble number have gone astray after strange gods, serving their bellies and their own lusts,” rather than cooperating in efforts to help the Saints provide for one another. [9] Such chronic dissension widened the already existing rifts.

Brannan faced another difficult and perplexing challenge as the New Hope Colony declined into an abyss of suspicion and greed. Feeling it was commensurate with his status as presiding elder, William Stout claimed for himself all the acreage that had been improved and tilled, as well as the first house built there.

Brannan knew he had to contact Brigham Young, not only to tell him of the paradise he had found in California, but also to obtain advice and support in dealing with his increasingly contentious and dwindling flock. Leaving William Glover in charge of the settlement, Brannan set out on 4 April 1847 to meet President Young on the Plains. [10]

The first stop was the New Hope Colony, where, after trying to reason with Stout, Brannan settled the issue by expelling him. Despite difficulties, the Saints did plant several acres of crops, but, as John Horner admitted, since it was “late in the season, and the grasshoppers numerous, we got only experience from this venture.” [11]

The next stop was Sutter’s Fort, where Brannan found an experienced trail guide, Charles Smith (said to have been a Latter-day Saint in Nauvoo), to accompany him together with another unnamed young man. The thousand-mile journey through Indian country and harsh natural conditions was hazardous for such a small party, attesting to Brannan’s courage and the urgency he felt.

Brannan wrote:

We crossed the Snowy Mountains of California, a distance of 40 miles, . . . in one day and two hours, a thing that has never been done before in less than three days. We traveled on foot and drove our animals before us, the snow from twenty to one hundred feet deep. When we arrived through, not one of us could scarcely stand on our feet. The people of California told us we could not cross them under two months, there being more snow on the mountains than had ever been known before, but God knows best, and was kind enough to prepare the way before us. [12]

The Mormon Battalion in California

While Brannan traveled east, members of the Mormon Battalion were helping to build Southern California. Hostilities related to the Mexican War had barely ceased when the Battalion arrived. In December 1846, the forward contingent of Gen. Stephen W. Kearny’s Army of the West, which had preceded the Battalion by about one and one-half months, secured the peace. By 10 January 1847 the American flag was hoisted over Los Angeles, and three days later, just two weeks before the Battalion soldiers first sighted the Pacific, John C. Fremont accepted the final surrender of Mexican forces. Hence the Battalion’s service in California was not primarily military in nature. Furthermore, its assignments were influenced more by the power struggle between Colonel Fremont and General Kearny than by the conflict between the United States and Mexico.

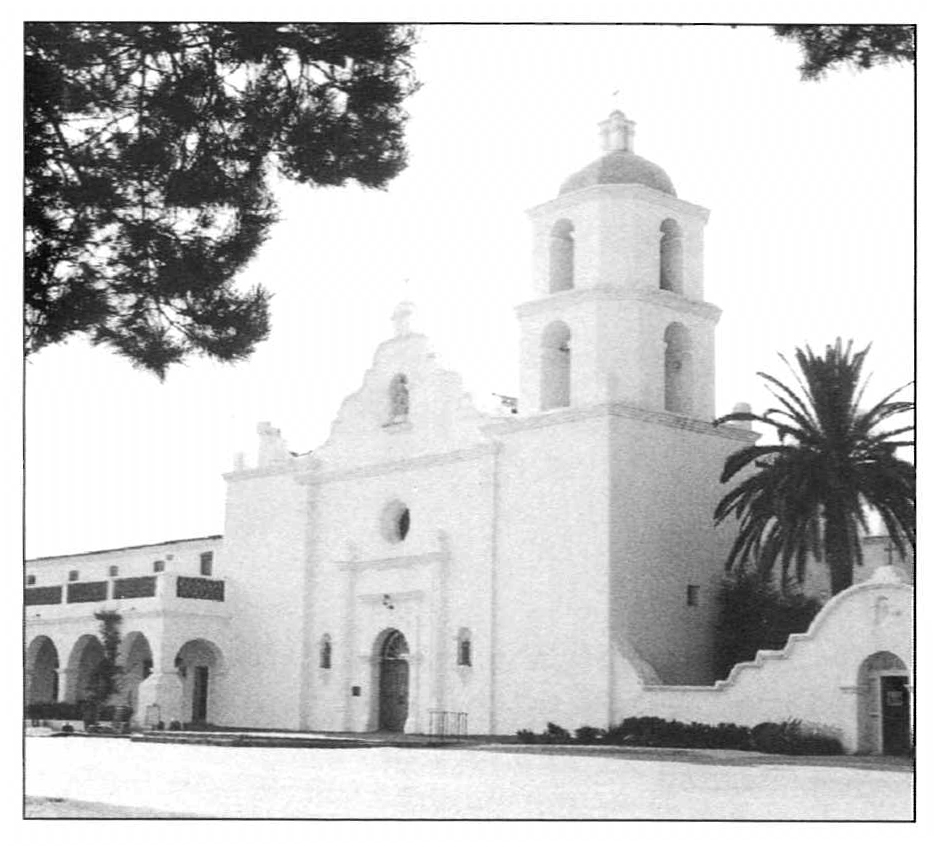

After only two days in San Diego, the Battalion was ordered to go to San Luis Rey, about forty miles north. Arriving there on 3 February, the soldiers found a decrepit and abandoned Franciscan mission situated in another beautiful and fertile winter valley. This was also a strategic location from which they could be ordered into action, if needed, to defend San Diego against a Mexican invasion or to check Fremont should he attempt to take over Los Angeles. While stationed at San Luis Rey, the soldiers improved their skills in military drills and skillfully cleaned and repaired the mission buildings. Perhaps more important, they demonstrated their good behavior and loyalty to Colonel Cook and General Kearny.

San Luis Rey Mission

San Luis Rey Mission

As the Latter-day Saint soldiers conducted religious activities at San Luis Rey, the long-festering conflict between their own military and spiritual leaders worsened. [13] Jefferson Hunt, whom Brigham Young had appointed captain of Company A, claimed authority to call and direct religious services. Levi Hancock, however, criticized Hunt and the other captains, saying they had been deficient in living the gospel, and refused to defer to their military rank. As one of the original Seven Presidents of the Seventy called to serve directly under the Twelve, Hancock believed he should take the lead in spiritual matters and thus made his own plans for worship services. Together with David Pettigrew, he also initiated ceremonial washings and anointings in hopes of sparking a spiritual revival. [14]

In March, Company B, with only two hours’ notice, was sent back to San Diego to assume garrison duty. [15] The industriousness and good behavior of these Latter-day Saint soldiers in San Diego helped overcome deceitful rumors and prejudice and earned them a favorable reputation. Army doctor John S. Griffin reported that “the prejudice against the Mormons here seems to be wearing off—it is yet among the Californians a great term of reproach to be called a Mormon—yet as they are a quiet, industrious, sober, inoffensive people—they seem to be gradually working their way up—they are extremely industrious—they have been engaged while here in digging wells, plastering houses, and seem anxious and ready to work.” [16]

In San Diego, Company B organized among themselves debating teams, a chorus, and other educational and cultural activities—something which the citizens found unusual for soldiers. They also constructed a kiln and fired forty thousand bricks, with which they paved sidewalks and lined several of the fifteen or twenty wells they had dug. They built a brick courthouse, which also served as a school. [17]

Before the Battalion came, residents of San Diego had been able to procure water only at some distance from town. The soldiers’ proposition to dig a well in the village was met with scorn by the townsfolk. Nevertheless, a thirty-foot well was dug and abundant water of a superior quality became available. An American sailor described how the locals would “hardly take time to finish their breakfast in the morning, but out they go and SIT AROUND THE WELL, smoke their cigaritos, while one of the party is everlastingly drawing up a bucket for the edification of the company.” [18]

“I think I whitewashed all San Diego,” Battalion member Henry G. Boyle recalled. “We did their blacksmithing, put up a bakery, made and repaired carts, and, in fine, did all we could to benefit ourselves as well as the citizens.” [19] Appreciative local residents petitioned the military to keep the Battalion there. When told that it was impossible, they asked that another contingent of Mormons take their places. “When we came to leave the place,” one of the soldiers recalled, “they seemed to cling to us, as though they had been parting with their own children.” [20]

Meanwhile, when Col. Philip St. George Cooke left San Luis Rey for Los Angeles on 19 March, he took the four remaining companies of the Battalion with him. When they arrived in Los Angeles four days later, the soldiers were impressed with the beautiful ranches, orchards, and vineyards surrounding the small town. The day after their arrival, Fremont’s “California Volunteers” would not recognize the authority of Kearny and Cooke and refused to turn over their artillery. Cooke declined to press the issue because he feared that by so doing he might fan into “civil war” the long-standing antagonism between his Mormon troops and the Missourians among Fremont’s Volunteers. [21]

One of the Saints recorded that Fremont’s men had “been using all possible means to prejudice the Spaniards and Indians against us by telling them we would take their wives &c. thereby rousing an excitement through the country.” [22] Occasionally, the Latter-day Saints and “bullies” among the former Missourians clashed in town. Regular soldiers of the First Dragoons sometimes came to the defense of the Battalion men, telling them, “Stand back; you are religious men, and we are not; we will take all of your fights into our hands” and with an oath promising, “You shall not be imposed upon by them.” [23]

Colonel Cooke ordered the men to enlarge the breastwork which had been constructed the previous January on the hill overlooking Los Angeles. At first, twenty-eight men from each company put in ten-hour days building the fort, members of the crew being rotated every four days. However, as the threat of conflict subsided the pace of construction slackened. [24]

On 8 May, Colonel Cooke sent a detachment of twenty Battalion men to protect Isaac Williams’s Rancho Santa Ana de Chino, near present-day Pomona. This was the beginning of a long-lasting relationship between Williams and the Saints. While on patrol, some of the Battalion surprised a small group of marauding Indians. Amid the ensuing conflict, five Indians were killed and two Battalion men slightly wounded. This was “their first and only battle with other humans in which blood was spilled.” [25]

A Fourth of July celebration featured the raising of the U.S. flag on the new 150-foot flagpole—the first such celebration in the little village of Los Angeles. The New York Volunteers band, which had come from Santa Barbara, played the “Star-Spangled Banner,” and the First Dragoons fired a thirteen-gun salute. An officer read the Declaration of Independence while the soldiers stood in formation. Levi Hancock then sang a patriotic song which he had earlier composed. On this occasion, Fort Moore was officially dedicated—named for Capt. Benjamin D. Moore, a member of Kearny’s First Dragoon who was killed the previous December in the Battle of San Pasqual. [26] Over a century later, a large memorial, adjacent to the Los Angeles civic center, would commemorate Fort Moore.

While these events were unfolding in Southern California, Gen. Steven W. Kearny and Col. John C. Fremont headed east to Washington—Kearny to make his report to the president and Congress, and Fremont, following slightly behind, to stand trial for insubordination and usurpation of authority in declaring himself governor of California. General Kearny chose fifteen Mormon Battalion soldiers to go with him as his personal escort. This honor denoted a marked contrast to his denouncement of Fremont’s California Volunteers for their poor treatment of local residents. The general assured the Battalion that his report of them would be favorable.

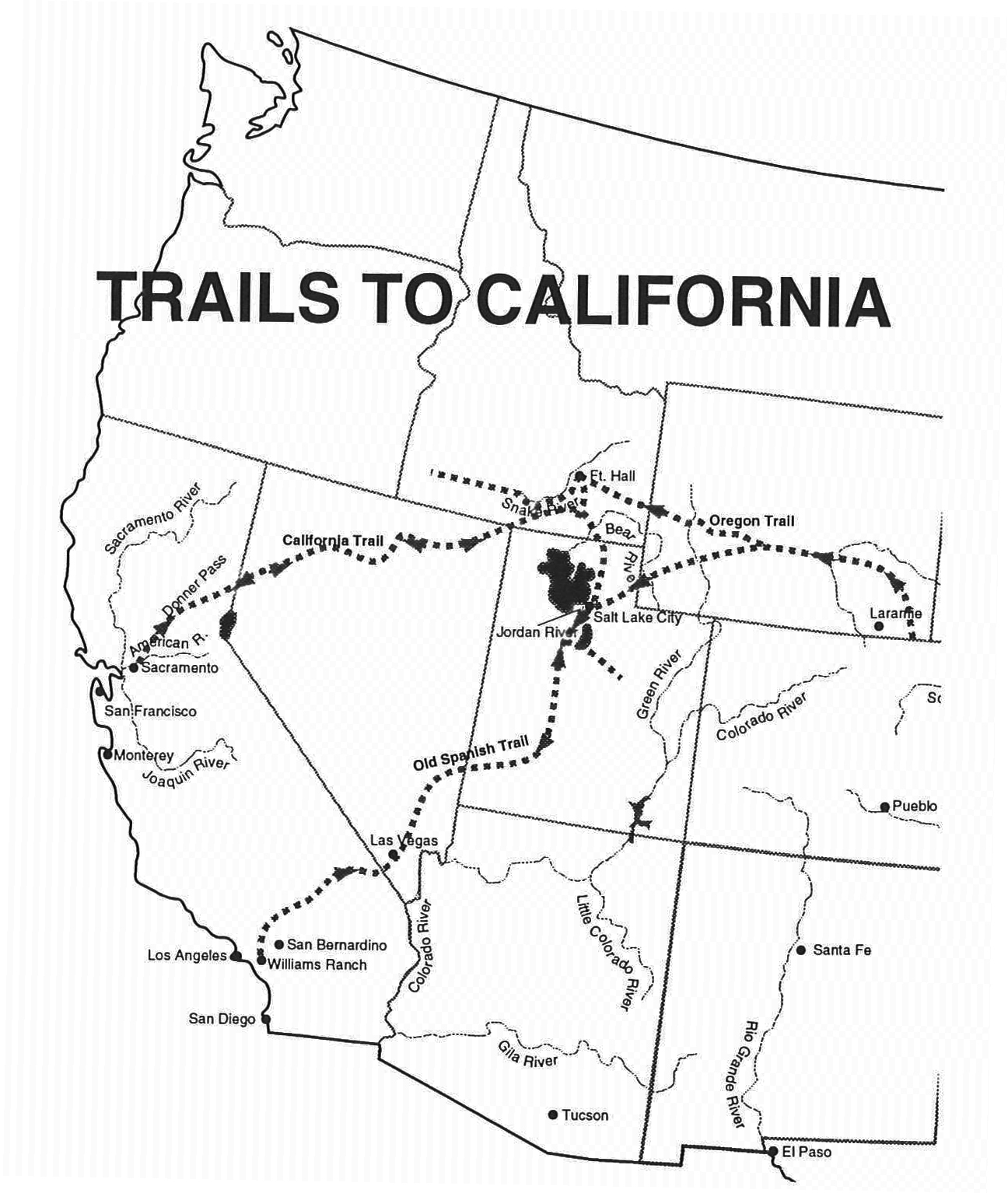

Leaving Monterey on the last day of May, this group followed the California Trail, the same route Samuel Brannan had taken a few weeks earlier. Upon reaching Fort Leavenworth on 22 August, members of the Mormon escort were discharged, each receiving a payment of $8.60 for his extra five weeks of service. Within a week, these soldiers traveled up the Missouri River to Winter Quarters, where they gave the Saints their first eyewitness report of the Battalion’s activities. [27]

Meanwhile, Battalion members in California became increasingly anxious to hear about their families and the main body of the Church. Their anxiety was heightened by the few fragmentary and confused reports they were able to receive. For example, a passenger on a sailing vessel told the men in San Diego that “a party of Mormons had been caught in the snows while crossing the Sierra Nevadas. The few that survived existed on human flesh.” [28] The Battalion men had no way of knowing that this report referred to the comparatively small Donner Party rather than to the great Latter-day Saint exodus. Another report indicated that Samuel Brannan had gone east across the mountains to meet the main Pioneer company under Brigham Young and to lead them to California, and that “the brethren at San Francisco were doing all in their power to prepare a home for their friends.” [29]

As 16 July, the end of the Battalion’s year-long enlistment, drew near, the men had to decide whether to reenlist. Jefferson Hunt and other Battalion officers, believing that the Saints would ultimately “settle in the vicinity of the Bay of San Francisco,” favored another year of service. However, the rank and file, influenced by Levi Hancock and other religious leaders, favored an early discharge because the war with Mexico had already ended. [30] Henry W. Bigler reported that “all hands were now busy making preparations to leave for their homes wherever that was; whether on Bear River, California, or Vancouver Island up in the British possession. For the truth is we do not know where President Young and the Church is!” [31]

California’s military governor, Richard Mason, wrote to the adjutant general in Washington concerning the Mormon Battalion:

Of services of this battalion, of their patience, subordination, and general good conduct, you have already heard; and I take great pleasure in adding that as a body of men they have religiously respected the rights and feelings of these conquered people, and not a syllable of complaint has reached my ears of a single insult offered or an outrage done by a Mormon Volunteer. So high an opinion did I entertain for the battalion, and of their special fitness for the duties now performed by the garrisons in this country, that I made strenuous efforts to engage their services for another year. [32]

Many promises were made to induce the Battalion members to reenlist, including one that the government would pay to have their families transported to California to join them.

On the appointed date, the Battalion’s companies were gathered at the nearly completed Fort Moore to either reenlist or be mustered out. They had put in a long year and were anxious to be reunited with their families. Nevertheless, eighty-one chose to reenlist. [33] Henry G. Boyle, one of those who reenlisted, explained his decision:

I did not like to reenlist, but as I had no relatives in the Church to return to, 1 desired to remain California til the Church became located, for it is impossible for us to leave here with provisions to last us any considerable length of time. And if I Stay here or any number of us, it is better for us to remain together, than to Scatter all over Creation. [34]

The eighty-one men who reenlisted were organized into the “Mormon Volunteers” and assigned duty in San Diego. Learning this, the residents there “anxiously awaited” the soldiers’ return. “Some even went out to greet the returning soldiers a day before they came.” [35]

The majority of those who were discharged chose to go to Northern California to find work in San Francisco or at Sutter’s Fort before rejoining their families. Three miles outside Los Angeles, these soldiers met at an appointed spot in a rivergrove to make preparations for their journey. Within a few days two large groups headed north, one captained by Jefferson Hunt along the coast and one by Levi Hancock inland. Thus the rift between the Battalion’s military and religious leaders was now reflected in an actual split into two groups. The largest group, 164 men led by Levi Hancock and David Pettigrew, organized themselves in ancient Israelite fashion, with captains of tens, fifties, and hundreds. Taking the central route into the San Joaquin Valley, they reached Sutter’s Fort on 26 August.

When Jefferson Hunt discussed the possibility of recruiting an entirely new Mormon Battalion to serve under his leadership, army authorities in Southern California suggested he detour, via the coastal route to Monterey, and present this idea to Governor Mason. [36] Hunt’s group of about one hundred reached Monterey on 10 August, where Mason endorsed Hunt’s proposal. While most of the group continued on to the San Francisco Bay Area to find work, three stayed in Monterey to work as carpenters and roofers on several buildings, including the town hall.

Members of the Hunt and Hancock groups reunited at Sutter’s Fort. Since “many of them were poorly clad, and otherwise short of means to fit themselves out for Salt Lake,” they took employment with Captain Sutter. Hiring about fiftysix of the “Mormon boys” enabled him to move forward with his plans to build a gristmill on the American River about four miles from his fort and also a sawmill at Coloma nearly forty miles further upstream. At the same time he “had at Coloma nearly three hundred thousand bushels of wheat to harvest and thresh.” [37] The remainder of the soldiers then turned east to cross the Sierra Nevada en route to rejoin their families and the main body of the Saints.

Brannan Meets the Pioneers

After passing through Fort Hall (in present-day Idaho), Samuel Brannan arrived on 30 June at Brigham Young’s camp on the Green River in present-day Wyoming. Pioneer William Clayton recorded: “After dinner . . . Elder Samuel Brannan arrived, having come from the Pacific to meet us, obtain counsel, etc.” [38]

President Young listened patiently as Brannan, using his best salesmanship, enthusiastically laid before him all the obvious reasons for settling in California. However, the wise Church leader was not impressed. He had consistently maintained that the main body of the Church would locate eight hundred miles inland from the coast in the Rocky Mountains. Furthermore, he had seen the final destination in a vision, and Brannan’s descriptions did not sound like the right place. Most importantly, the better Brannan made California sound, the more President Young knew it could never provide permanent peace, since it would also appeal to the Saints’ enemies. He later remarked: “When the pioneer company reached Green River we met Samuel Brannan and a few others from California, and they wanted us to go there. 1 remarked: ‘Let us go to California, and we cannot stay there over five years; but let us stay in the mountains, and we can raise our own potatoes and eat them; and I calculate to stay here.’” [39]

As Brannan tarried with Brigham Young at the Green River, an advance party from Pueblo, Colorado, representing the group of Battalion sick and some southern Saints, approached the camp. One of these scouts was Elder Amasa M. Lyman, who had been a missionary among the southern Saints. He had been dispatched from Brigham Young’s main camp to provide leadership in Pueblo. Because some of the soldiers were considering returning east to their families rather than continuing west to California, as they had been enlisted to do, the Battalion’s reputation was at stake. Desertion by a few could mean loss of pay for many. Brannan was just the man needed to convince them to continue on to California. He was appointed to meet the Saints from Pueblo, who were under the charge of Capt. James Brown, a Mormon Battalion officer who was a Latter-day Saint, and to escort them to the main body of the Pioneers.

Brigham Young’s camp pressed on toward the Great Basin, arriving in the Salt Lake Valley on 24 July 1847. Just five days later, Brannan arrived with the Pueblo contingent. He was disappointed to learn that President Young was already planning a city in the valley large enough to accommodate those still remaining on the trail. President Young had also designated a temple site. Brannan’s hope that he could guide the main body of the Church to California was dashed. His trip was seemingly wasted.

While in the Salt Lake Valley waiting for Captain Brown and his party to make final preparations for the trip with him to California, Brannan accepted the invitation of his old friend, Elder Orson Pratt, to show the Pioneers how to make California adobe bricks. The adobe dwellings constructed that summer provided shelter for the Saints, including President Young’s family, to survive the following harsh winter.

Instead of sending all the Battalion soldiers on with Brannan, Brigham Young changed his mind and advised most of them to remain in the Salt Lake Valley and help out there, since their enlistment time had elapsed. He had their military leader, Captain Brown, discharge them and sent him to collect their final pay.

On 7 August, two days before Brannan and Brown left for California, Brigham Young, on behalf of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, wrote two letters of greeting to the Saints there. In the first letter, addressed specifically to members of the Mormon Battalion, he declared:

When you receive this and learn of this location, it will be wisdom for you all, if you have got your discharge as we suppose, to come directly to this place, where you will learn particularly who is here, who not. If there are any men who have not families among your number, who desire to stop in California for a season, we do not feel to object; yet we do feel that it will be better for them to come directly to this place, for here will be our headquarters for the present, and our dwelling place . . . and we want to see you, even all of you, and talk with you, and throw our arms around you. [40]

In the second letter, addressed to the California Saints as a whole, President Young praised the excellence of the Salt Lake Valley’s soil, water, and climate. He then added:

You are [also] in a goodly land; and if you choose to tarry where you are, you are at liberty so to do; and if you choose to come to this place, you are at liberty to come, and we shall be happy to receive you, and give you an inheritance in our midst. . . not that we wish to depopulate California of all the saints, but that we wish to make this a stronghold, a rallying point, a more immediate gathering place than any other; and from hence let the work go out, and in process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord. [41]

After getting outfitted at Fort Hall, the Brown-Brannan party followed the California Trail west. Along the way, Brannan and Brown parted company. One of the Battalion soldiers, Abner Blackburn, detailed their conflicts: “Brannan and Cap Brown could not agree on anny subject. Brannan thought he knew it all and Brown thought he knew his share of it. They felt snuffy at each other and kept apart.” On 5 September in Truckee Canyon, their frictions came to a head: “Cap Brown wanted [to] travel on several miles before breakfast. Brannan said he would eat breakfast first. Brown sayes the horses would goe anny how for they belonged to the government and were in his care. They both went for the horses and a fight commenced. They pounded each other with fists and clubs until they were sepperated. They both ran for their guns. We parted them again.” The group parted and Brannan rode on ahead. [42]

The next day, near Donner Lake, Brannan intercepted the approximately 140 Battalion soldiers heading east. He shared Brigham Young’s counsel that those who did not have sufficient provisions to winter in the Salt Lake Valley should remain in California until spring. [43] Daniel Tyler recorded that Brannan’s description of the Salt Lake Valley “was anything but encouraging. . . . It froze there every month. . . . [T]he ground was too dry . . . . [If] irrigated with the cold mountain streams, the seeds planted would be chilled and prevented from growing, . . . [and] all except those whose families were known to be at Salt Lake had better turn back and labor until spring, when in all probability the Church would come to them.” [44]

The following day, Captain Brown’s party came into camp. After he shared with them the letter he was carrying from the apostles, about half of the soldiers decided to continue east under Levi Hancock’s leadership. Apparently, Hancock and Jefferson Hunt forged at least a partial reconciliation, because Hunt also went with the group. They reached the Salt Lake Valley in October. Some, whose families were not yet there, immediately went on to Winter Quarters, arriving in December. Of those who returned to the settlements in California, about half found work with Sutter. [45] This leftover five hundred Saints in California: eighty reenlistees in San Diego and four to five hundred scattered about the state, mostly in the North.

Among the Battalion men who parted were a father and son who had served together for over a year. Albert Smith went on to the Great Basin while his son Azariah, who had just celebrated his nineteenth birthday, returned to Sutter’s Fort. [46]

Brannan also traveled on to Sutter’s Fort. There he and his trail partner, Charles Smith, rented a one-room adobe, acquired a small boat to bring merchandise from San Francisco, and set up a general store. [47] Smith remained at Sutter’s Fort to manage the store. This little enterprise became a foundation that eventually brought Brannan unimagined wealth.

Meanwhile, Captain Brown, accompanied by his son, Jesse, went on to San Francisco then headed south to Monterey. There he met Governor Mason, who ordered the paymaster to give Brown ten thousand dollars in Spanish doubloons (nearly a million dollars in today’s currency) as payment in full for his service and the service rendered by the Battalion members who had not been able to complete the march to the Pacific because of illness. Brown immediately transported the gold to the Salt Lake Valley, arriving on 15 December. After paying the soldiers, Brown, with Church leaders’ sanction, used the remaining three thousand dollars to purchase a ranch with a few dilapidated buildings at the mouth of Weber Canyon. There, “Brownville” was settled by James Brown and others who were deeded plots of land on the ranch. This settlement grew into the city of Ogden, Utah. The ranch also contained the Great Basin’s only established cattle herd. It supplied milk, meat, and cheese, which allowed the Pioneers to survive their first harsh winter. It is said that the ten thousand dollars in gold doubloons was virtually the only money circulated in Utah until miners brought gold from California the following year. [48]

Brannan’s Return to San Francisco

While Brannan was away, growth continued in San Francisco (as Yerba Buena was now called because of an order ascribed to Mayor Bartlett). [49] Two auctions were held for San Francisco city lots, which were purchased in just a few hours, many by Latter-day Saints. The Star disclosed that as of 30 June the town’s population had reached 459 and that half of its 157 buildings had been constructed since 1 April. [50] Thus in less than one year, Church members had likely erected more than one hundred dwellings for themselves, their families, and their community.

At about this time, Addison Pratt arrived in San Francisco from his mission in the Society (Tahitian) Islands. He discerned discord existing among the San Francisco Saints:

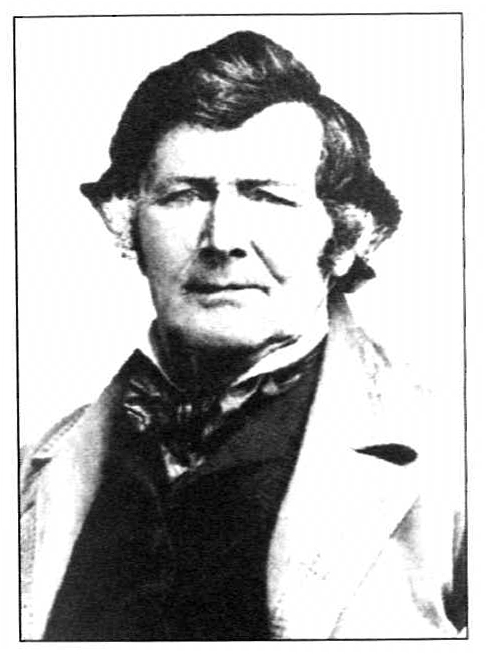

Addison Pratt

Addison Pratt

There was much dissatisfaction among the Brooklyn brethren as to Brannan’s proceedings while on board of the Brooklyn, and several of them proposed to me to take charge of the spiritual affairs among them. But I told them it was not my place to meddle with their affairs in any wise as Brannan was the man that was appointed by the church to look after them, and my mission was to another part of the world altogether. [51]

Upon Brannan’s return to San Francisco on 17 September 1847, he wrote to Jesse Little:

“I found everything on my return far better than my most sanguine expectation. . . . When I landed here with my little company there was but three families in the place and now the improvements are beyond all conception. Houses in every direction, business very brisk and money plenty. Here will be the great Emporium of the Pacific and eventually of the world.” Brannan was a man of vision: if California were accounted as a separate country today, it would rank seventh in the world economically.

Although apprehensive comments were heard before the Saints’ arrival, attitudes had already changed dramatically. Brannan gratefully acknowledged in his letter to Jesse Little that “the Mormons are A No. 1 in this country.” [52] William Glover had just been elected to San Francisco’s original six-member town council and a few days later was appointed to the school board. [53]

President Young’s August letter to the California Saints had counseled: “We do not desire much public preaching or noise or confusion concerning us or our religion in California at the present time.” It also expressed support for Brannan’s leadership:

We are satisfied with the proceedings of Elder Brannan. We believe that he is a good man and that it is his design to do right. No doubt that he has been placed in very trying circumstances in connection and common with you, since your journey to California was first contemplated; and if he or you have erred . . . we feel to exhort you at all times to cultivate the spirit of meekness, kindness, gentleness, compassion, love, forgiveness, forbearance, long-suffering, patience, and charity one towards another; and look upon others faults and follies as you want others to look upon yours; and forgive as you want to be forgiven.

President Young also urged the Brooklyn Saints to honor the balance of the three-year compact to labor “unitedly for the good of the whole.” [54]

The Church’s decision to settle in the Great Basin rather than going to the Coast changed the plans of many of the California Saints. “You can imagine our disappointment,” William Glover recalled. The company was broken up as many Saints began making preparations for going to the mountains. Glover also disapproved of what happened at New Hope: “The land, the oxen, the crop, the houses, tools, and launch, all went into Brannan’s hands, and the Company that did the work never got anything for their labor.” [55] In October, contrary to Brigham Young’s counsel, Brannan took steps to liquidate the common fund. In the Star, he advertised that all the holdings of “the firm of S. Brannan & Co.” were for sale. [56]

A few days later, Samuel Brannan wrote to Brigham Young and the Twelve:

I hope, brethren, that you will not suffer your minds to be prejudiced or doubt my loyalty from any rumors. . . . I want your confidence, faith and prayers, feeling that I will discharge my duties under all circumstances, and then I will be happy. . . . To you I stand ready at any moment to render an account of my stewardship. [57]

Over two years would pass before Brannan would have any face-to-face contact with higher Church leaders.

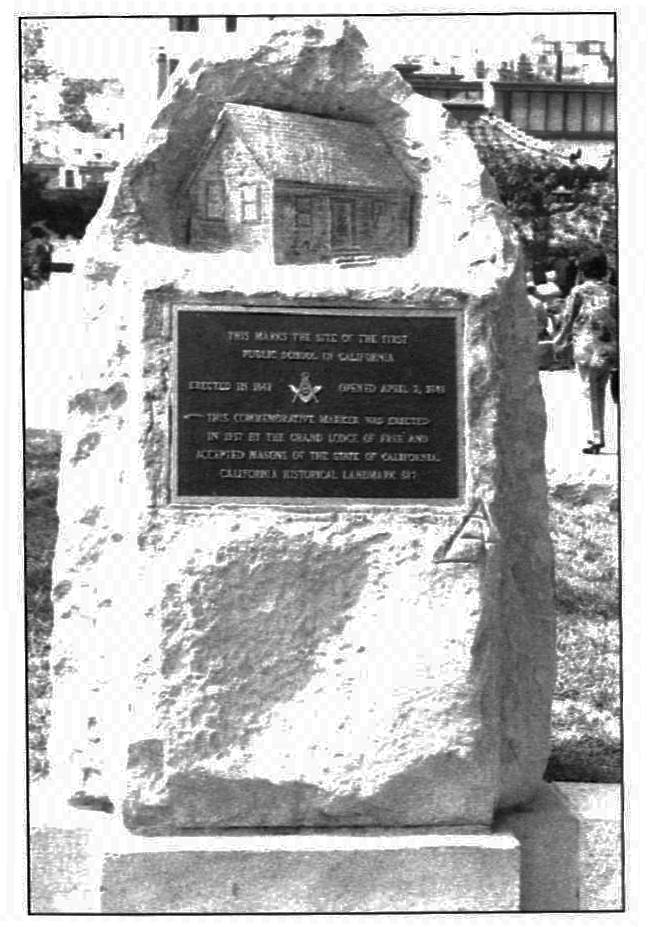

With the group planning to leave and the Church discouraging overtly religious activity, Brannan increasingly channeled his energy into civic and business enterprises. He continued drumming up support in the Star for a public school. As early as the paper’s second issue, he had offered to donate a plot of land and fifty dollars to erect one. By December, San Francisco’s first schoolhouse was completed on Clay Street next to the plaza. [58] A memorial, erected by San Francisco’s Centennial Commission and local Masonic lodge, stands today in Portsmouth Square in recognition of that school.

Monument to San Francisco's first schoolhouse,

Monument to San Francisco's first schoolhouse,

at Portsmouth Square

On 2 December, Brannan called a meeting to organize the San Francisco Branch with Addison Pratt as president. Disconcerted, Pratt recorded:

To my presiding, I objected perhaps too strongly, but not withstanding, they voted me in, and I then felt it my duty to act. Strong accusations were presented against Brannan by the “Brooklyn” company to the effect that he had devised ways and means whereby he had swindled them out of their property with the pretense that he was collecting for the church. . . . But there were two parties, one for Brannan, and the other against him, and the Battalion boys gradually allowed themselves to be drawn in some on the one side and some on the other, and party feelings were thus fast growing in spite of my best efforts to keep it down. . . . I also learned that Br. Brannan expected me to rule the branch, and that 1 in turn was expected to be ruled by him. But when he found that I had some notions of my own that should be consulted, I became very obnoxious to him. [59]

Soon Brannan, Pratt, and the entire Latter-day Saint colony were overcome by a tide of unforeseeable events that swept away the branch and the town’s recently planted spiritual roots.

Notes

[1] Bernard de Voto, The Year of Decision, 1846 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1943).

[2] Quoted in Millennial Star 9 (15 October 1847): 307.

[3] Ibid., 306.

[4] Hubert H. Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: The History Co., 1886), 5:552.

[5] Annaleone D. Patton, California Mormons by Sail and Trail (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1961), 67.

[6] George R. Stewart, Ordeal By Hunger: The Story of the Donner Party (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988), 191.

[7] California Star, 16 January 1847.

[8] Stewart, 243–16.

[9] Millennial Star 9 (15 October 1847): 306.

[10] Andrew Jenson, comp., “The California Mission” (hereafter CM); LDS Church Archives.

[11] John Horner, “Voyage of the Ship ‘Brooklyn,’” Improvement Era 9, no. 10 (August 1906): 795.

[12] Millennial Star 9 (15 October 1847): 305.

[13] Larry D. Christiansen, “The Struggle for Power in the Mormon Battalion, Dialogue 26, no. 4 (winter 1993): 51–69.

[14] John F. Yurtinus, “A Ram in the Thicket: The Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1975), 539–42.

[15] Ibid., 543–45.

[16] Ibid., 557.

[17] Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War (Glorieta, N. Mex.: 1881), 290; Henry W. Bigler, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West, ed. Erwin G. Gudde (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962), 61.

[18] Capt. S. F. DuPont, Extracts from Private Journal-Letters, quoted in Yurtinus, 561.

[19] Quoted in Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Tress, 1952), 65.

[20] William Hyde Diary, June 1847, quoted in Yurtinus, 561.

[21] Yurtinus, 500.

[22] Frank A. Golder, The March of the Mormon Battalion: From Council Bluffs to California (New York: The Century Co., 1928), 219.

[23] Tyler, 280.

[24] Encyclopedia of Historic Forts (New York: Macmillan, 1988), 80; Yurtinus, 572.

[25] Yurtinus, 574.

[26] Ibid., 579–80.

[27] Ibid., 504–26.

[28] Ibid., 555.

[29] Quoted in ibid., 556.

[30] Colder, 227–30; Yurtinus, 585–89, 591–92; see also Susan E. Black, “The Mormon Battalion: Conflict Between Religious and Military Authority,” Southern California Quarterly 74, no. 4 (winter 1992): 324–25.

[31] Bigler, 57 n. 19.

[32] Quoted in Bancroft, 5:492 n. 20.

[33] Yurtinus, 607.

[34] Henry G. Boyle Diary, 20 July 1847; typescript, Brigham Young University Archives.

[35] Yurtinus, 612–13.

[36] Pauline Udall Smith, Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion (Salt Lake City: The Nicholas G. Morgan, Sr., Foundation, 1958), 122.

[37] The Journals of Addison Pratt, ed. S. George Ellsworth (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 335.

[38] William Clayton’s Journal (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1921), 281.

[39] Preston Nibley, Brigham Young: The Man and His Work (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 97.

[40] Journal History, 7 August 1847 (hereafter JH); LDS Church Archives.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Abner Blackburn, Frontiersman: Abner Blackburn’s Narrative, ed. Will Bagley (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1992), 65, 102.

[43] CM, 18 September 1847; Homer, 30–31.

[44] Tyler, 315.

[45] Yurtinus, 630–32.

[46] Azariah Smith, The Gold Discovery Journal of Azariah Smith, ed. David L. Bigler (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 102–3.

[47] Although Sutter later recalled the partner’s name as George Smith or Gordon Smith, he was probably the same Charles Smith who served as Brannan’s guide.

[48] Archie Leon Brown and Charlene L. Hathaway, 141 Years of Mormon Heritage (Oakland: Archie Leon Brown, 1973), 103–6.

[49] California Star, 30 January 1847.

[50] California Star, 28 August 1847 and 4 September 1847.

[51] Journals of Addison Pratt, 330.

[52] Samuel Brannan to Jesse C. Little, in CM, 18 September 1847.

[53] California Star, 18 September 1847.

[54] JH, 7 August 1847.

[55] William Glover, The Mormons in California (Los Angeles: Dawson, 1954), 21.

[56] California Star, 9 October 1847.

[57] JH, 17 October 1847.

[58] California Star, 16 January 1847 and 4 December 1847.

[59] CM, 24 January 1848.