World War II: 1939–1945

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 301–16.

World War II was perhaps the most significant, defining event of the twentieth century. It changed the way America viewed itself and the rest of the world. Prior to the war, the United States looked primarily eastward toward Europe, cradle of its culture and language and the origin of 85 percent of its immigrants. However, this war reminded the nation that its western shore faced the great cultures of Asia, which began to play an increasingly important role in U.S. affairs. For the rest of the century, most of America’s major armed conflicts would be in Asia, and military operations would be funneled primarily through California. During this same time, a growing tide of Asian immigrants and products would flow toward California.

The war’s repercussions in California were particularly great—altering the face of the state psychologically, economically, technologically, and sociologically. World War II profoundly changed California’s demographics in ways that continued to be felt for decades. War-related activities accelerated America’s internal population shift toward the Pacific Coast. The war also intensified California’s ethnic diversity as hundreds of thousands of American Blacks came to work in California’s war industries, permanently adding large numbers of African American faces to the Anglo, Mexican, and Asian ones that had already been important parts of the state for a century or more. Finally, the war triggered a population bubble called the “baby boom,” as many children were born just after the war ended. The war began in Europe where Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party first rose to power in Germany then set out on a path of conquest. For a while, the United States, still smarting from the Great Depression and World War I, remained on the sidelines. However, as it became increasingly apparent that without American action Hitler could prevail, the United States reluctantly became more involved—largely ignoring the growing threat on its western flank.

But on 7 December 1941, when the Japanese launched a surprise air attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, America’s attention was suddenly diverted westward. California Saints were just leaving their morning Sunday School services when reports of this event reached the mainland. Some heard the news on their car radios as they drove home.

A Future Prophet Begins His Ministry

As these scenes unfolded, a future president of the Church, Howard W. Hunter, began his service as a bishop in Los Angeles. Though he had Latter-day Saint Pioneer ancestors, his father’s family had drifted away from Church activity. Young Howard was not baptized until he was twelve rather than at the accustomed age of eight. In the late 1920s, he was among those transplants whose faith deepened in California. Although he had participated in Church activities while growing up in Idaho, he later acknowledged that his “first real awakening to the gospel” resulted from attending Peter A. Clayton’s Sunday School class in the Los Angeles Adams Ward. Brother Clayton had a wealth of knowledge on gospel topics and was able to motivate the young members of his class by assigning them to speak on specific gospel themes. “I think of this period of my life as the time the truths of the gospel commenced to unfold,” Howard W. Hunter later recalled. “I always had a testimony of the gospel, but suddenly I commenced to understand.” [1]

As a young father and cum laude law school graduate, he became the first bishop of Southern California’s new El Sereno Ward on 1 September 1940. He said:

Such a call had never entered my mind, and I was stunned. I had always thought of a bishop as being an older man, and I asked how I could be the father of the ward at such a young age of 32. They said I would be the youngest bishop in Southern California, but they knew I could be equal to the assignment. [2]

The new bishop’s first task was to “find a place for meetings, get the ward organized and staffed, and get going.” He arranged to rent the local Masonic lodge for Sunday services and for an occasional Friday night activity. The rent was fifteen dollars a month. “We didn’t know where we were going to get $15,” Elder Hunter later reminisced, “but we survived.” [3]

The Latter-day Saints and Military Service

In May 1941, several months before the United States entered the war, the Church appointed Hugh B. Brown, who was living in Glendale, as servicemen’s coordinator. A former stake president and officer in the Canadian military during World War I, and future apostle and counselor in the First Presidency, he brought stature to this new calling. He began his assignment with a visit to a group of Latter-day Saint servicemen at San Luis Obispo. He next accompanied Elders Albert E. Bowen and Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve (the latter having been called as an apostle only a few weeks earlier) to San Diego, where several hundred Latter-day Saints were already stationed.

Wherever Hugh B. Brown went, he organized special branches for military personnel and made sure the servicemen were supplied with Church reading materials. [4] He delivered numerous inspirational sermons to military personnel—regardless of their religious affiliations—in open-air meetings, on board ships, in army huts, and in military chapels, canteens, and theaters. [5]

Hugh B. Brown recalls role as servicemen's coordinator

Hugh B. Brown recalls role as servicemen's coordinator

From these beginnings in California, a Churchwide servicemen’s program developed. Because a large share of Latter-day Saints entering military service received their basic training in California, Brown and his associates played a key role. They officially appointed many of these young men to be “group leaders.” Wherever they were sent, they were authorized to conduct religious services and in other ways minister to the spiritual needs of their associates.

In the April 1942 general conference, four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the First Presidency outlined the Church’s position on war and gave counsel to Latter-day Saints in military service: “Hate can have no place in the souls of the righteous,” they declared, emphasizing the Savior’s injunction to love one another. However, as citizens, the Saints should “render that loyalty to their country and to free institutions which the loftiest patriotism calls for. . . . Both sides cannot be wholly right; perhaps neither is without wrong.” The First Presidency exhorted the young men and women in military service to “live clean, keep the commandments of the Lord, pray to Him constantly to preserve you in truth and righteousness, live as you pray, and then whatever betides you the Lord will be with you. . . . Then, when the conflict is over and you return to your homes, having lived the righteous life, how great will be your happiness—whether you be of the victors or the vanquished—that you have lived as the Lord commanded.” [6]

Heeding the counsel of their Church leaders, Latter-day Saints responded when calls for military service came. Many servicemen were trained in California before being shipped overseas. Hence, wards and stakes in the Golden State became heavily involved in the various programs the Church implemented for servicemen. These local units frequently sponsored dances and other events to which the servicemen were invited. “Budget cards” became passports to these Church social and recreational activities.

Many Latter-day Saints in the military shared their beliefs with others. Numerous conversions resulted from the worthy examples of LDS friends, both in California and overseas. As a result, many small branches of local members sprouted in the Pacific and East Asia. Growth in these areas would impact the Church in California throughout the rest of the century, as members from these regions migrated to the state.

Saints in the War Industries

One of the greatest challenges the war brought to California resulted from rapid population growth and escalating defense spending. California’s population had already exploded. The growth of the 1920s and 1930s, the largest migration in the world’s history, was now eclipsed. The number of newcomers during the 1940s was greater than the total of the previous two decades combined (see appendix B). Between 1940 and 1946 the U.S. government injected an average of seven billion dollars per year into the state’s economy. Even without war, that amount would have done severe violence to the state’s social and economic structure, for it was nearly twice the average annual value of the previous years’ total economic output. [7]

California became one of the major manufacturing states in the nation. In Southern California the aircraft industry mushroomed from a scant twenty thousand workers in 1939 to more than 243,000 four years later. [8]

Another large industrial effort was shipbuilding. The Bay Area port of Richmond built a series of “Liberty ships” named for American heroes. One of those was the cargo ship Joseph Smith, built by the Kaiser shipyard and launched on 20 May 1943. The Oakland Stake president, Eugene Hilton, represented the First Presidency at the christening of this ship named for the Church’s founding Prophet. Special music was provided by the Oakland Stake, and many members attended the ceremonies. [9]

These manufacturing efforts swiftly exhausted the state’s available labor supply, so California industries recruited workers from all over the country. The inducements were considerable. Weekly earnings nearly doubled, and those working in essential wartime industries were exempt from the draft. California’s high wages and mild climate were powerful attractions. As a result, the total number of manufacturing workers increased from 461,000 in 1940 to 1,186,000 in 1943. [10] Thus, almost overnight, what had been a large and important state became the giant of the West, a state larger, more populous, and more prosperous than most independent countries.

Though the pace of the general migration was fast, the influx of Latter-day Saints to California continued to be even greater. LDS population grew from one in 150 in 1940 to one in 120 in 1945. The Church’s percent of California’s population was higher than its percent in the nation as a whole. Between 1940 and 1950, California’s LDS population grew 128 percent, from 44,800 to 102,000.

The war impacted the Saints and Californians in other distinctive and significant ways. Large numbers of women left traditional roles as full-time homemakers and took places on factory assembly lines to alleviate the labor shortage. “Rosie the Riveter” not only became a wartime heroine but was the precedent for permanently altered roles for many women. Many of those whose husbands were away as soldiers went into the workplace to do their part to aid the war effort. However, rather than going back home when the war ended, many kept working, joined by ever larger numbers of women. Though Church leaders warned that removing mothers from traditional roles could have a significant impact on families, the number of working Latter-day Saint women continued to rise after the war.

The Effects of War

In January 1942, just a month after the Pearl Harbor attack, the First Presidency announced that in order to cut down on unnecessary travel, all stake leadership meetings for various Church programs would be suspended for the duration of the war. Later, other Church activities and large group gatherings had to be curtailed also, because of gasoline and tire rationing and because of the difficulties in obtaining automobiles. Those restrictions especially affected California, where traveling distances were typically longer.

Elder Harold B. Lee was convinced that the timing of the Church’s precautions was the result of revelation. Referring to the January 1942 restrictions on meetings and travel, he declared:

When you remember that all this happened from eight months to nearly a year before the tire and gas rationing took place, you may well understand if you will only take thought that here again was the voice of the Lord to this people, trying to prepare them for the conservation program that within a year was forced upon them. No one at that time could surely foresee that the countries that had been producing certain essential commodities were to be overrun and we thereby be forced into a shortage. [11]

The war changed Church activities in several other interesting ways. In certain areas, owing to fears of possible air raids, the military ordered all buildings “blacked out” at night. Latter-day Saint churches took on a somber look as opaque coverings were applied to all windows. If any light was seen coming from the building during evening air-raid drills, the “block warden” ordered the lights turned off. “Motorists were even instructed not to use their headlights at night. Local Church leaders therefore canceled as many evening activities and meetings as possible to facilitate compliance with the ‘black out’ regulations and to minimize risk to the members.” The Pasadena Stake, for example, moved its sacrament meetings from early evening to the afternoon. [12]

Building supplies were diverted for military use, so construction of meetinghouses also came to a halt, despite a rapidly growing Church population. Nevertheless, local congregations tried to accumulate money in hopes of having a chapel someday. Even though the El Sereno Ward could not build its badly needed meetinghouse during the war, Bishop Howard W. Hunter led his congregation in projects to earn money which they put aside for the time when they could proceed. For example, ward members tediously trimmed onions for a nearby pickle factory, and for a sauerkraut producer they shredded cabbages which were then stamped down in large vats by men in rubber boots. “It was easy to tell in Sacrament Meeting if a person had been snipping onions,” Bishop Hunter mused. [13]

He also encouraged family members to plant their own gardens and to work in the ward garden raising beans. “People in the neighborhood were amazed at the harvest we gathered,” one ward member recalled. [14] These gardens were part of a nationwide “Victory Garden” campaign for families and other groups to grow as much of their own produce as possible so that commercially grown products could be fed to soldiers. Some of the gardens in the Pasadena Stake were singled out for acclaim over national radio as a stimulus to encourage other Americans to become likewise involved.

Because of the building shortage, the Church organized fewer new stakes nationwide during the war and none in California. The Church did, however, divide the California Mission. This decision coincided with the outbreak of the war. Beginning in January 1942, the new Northern California Mission, a mission headquartered once again in San Francisco, was responsible for approximately four thousand members in forty-five branches scattered throughout Northern California, western Nevada, and southern Oregon. The California Mission continued to be headquartered in Los Angeles and had nearly thirty-seven hundred members in thirty-four branches, including some in Arizona. This division was fortunate because it cut down the number of miles the mission president had to travel. No longer would one man have to cover the vast state of California plus portions of three other western states as well. It also doubled the availability of a mission president to give leadership and counsel to servicemen and other members. Over the course of time, both stakes and missions would continue to be divided again and again.

The Church agreed not to call young men of draft age to go on missions. Hence the number of missionaries in California plummeted as more young men entered military service during the war. While 244 missionaries were serving at the end of 1941, the total dropped three years later to only seventy-two. [15] Members living in California again assumed more responsibility to make up for the shortfall, just as they had when the number of missionaries dropped a decade earlier during the Great Depression. These Saints accepted calls as local part-time missionaries and at the same time assumed greater roles in stake, ward, district, and branch organizations.

Church members often had to function in two or more callings simultaneously. For instance, Bishop Hunter also carried the weighty load of scoutmaster.

The cutbacks in Church personnel and programs came at the very time when the Church more than ever needed to reach the growing number of members cut free from the guiding and sustaining influence of home and family. These included thousands of LDS servicemen and servicewomen, as well as LDS youth who were seeking employment in California’s defense industries. Near the end of the war, more than half of the young men of high school and college age were living away from home. Church authorities encouraged local leaders to take a special interest in these youth. Despite the pressures of living away from home, however, the young Saints’ faithful adherence to Church doctrines and standards was actually strengthened during the war. In several areas the contribution of tithes and fast offerings and the attendance at Church meetings increased. The California groups stood among the top wards, stakes, and missions of the Church. This was in spite of the fact that the leadership burdens in California were perhaps larger than anywhere else in the Church because of the number of members that leaders had to serve and the distances involved in reaching them.

Church members became involved in a variety of activities to help with the war effort. Even the youth found ways to assist. During the winter of 1942–43, the Church’s twelve- and thirteen- year-old Beehive girls donated thousands of hours collecting scrap metal, fats, and other needed materials, making scrapbooks or baking cookies for soldiers, and tending children for mothers working in defense industries. A special “Honor Bee” award was offered for such service.

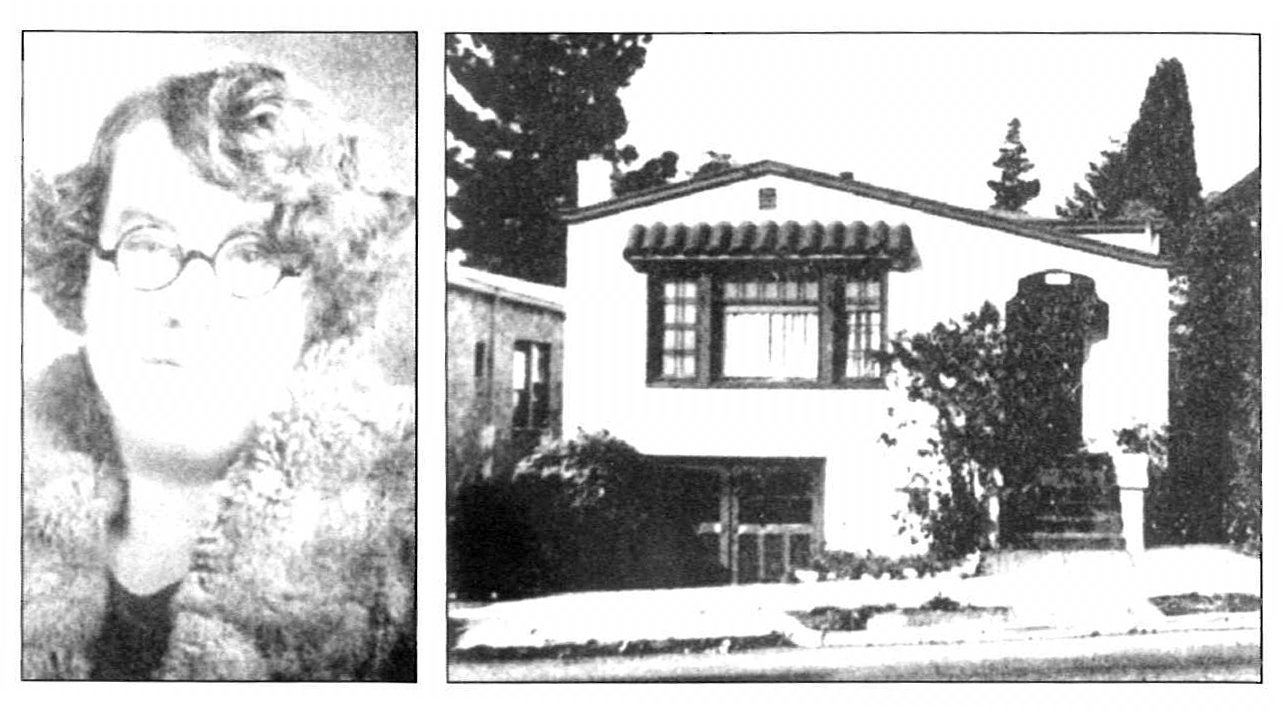

As the war dragged on, concerned Latter-day Saints in California established servicemen’s “homes away from home.” One was the five-room Berkeley residence of Stanley and Anna Patton, who were known as “Mom and Pop” Patton to thousands of servicemen and servicewomen. The Pattons made their basement into a free dormitory and put cots in the laundry room. The young men were given keys to these downstairs rooms, which they called “cot luck.”

Anna Patton and her home in Berkeley

Anna Patton and her home in Berkeley

But the Pattons’ home was more than a dormitory. They sponsored activities that ran the gamut—birthdays, engagements, weddings, births, baptisms, priesthood advancements, and farewells. On some occasions they even had to help with funeral arrangements.

After morning Sunday School, the Pattons invited two or three home for dinner. Each week there were a few more, and soon their home could not hold them all. So the sisters of the Berkeley Ward began hosting servicemen’s lunches at the chapel. After Sunday School they set up long tables and brought salads or vegetables—whatever they could spare—and combined these potluck items into dinners for the servicemen. At the war’s peak, as many as 150 were served dinner each week in the ward cultural hall. Rather than going with their buddies to movies, bars, or other less-desirable places, the servicemen were invited to spend the afternoon at the church until sacrament meeting began in the evening.

The servicemen brought wives, mothers, sisters, and sweethearts to meet “Mom and Pop.” For three years the LDS military personnel at nearby Treasure Island honored Sister Patton on Mothers’ Day with a special program. Over the years Anna compiled more than twenty scrapbooks of correspondence from servicemen and servicewomen as they scattered throughout the world. [16]

One group of California Saints severely affected by the war were those of Japanese ancestry. Fearing that Japanese Americans might become disloyal if the coast were attacked, overly cautious government officials ordered them to leave or be concentrated under armed guard in relocation centers. Some, such as Hideo “Eddie” Kawai and his extended family chose to move to Utah, where they could remain “close to the gospel and other members of the Church during wartime.” When the Kawais returned home after the war they were disappointed to find that they were still the victims of prejudice and were therefore especially grateful for “their true friends.” [17]

A Second Temple Site Secured

Despite the war, California Latter-day Saints still longed to have temples nearby. Even though no construction could be done, they, full of faith, drew plans for a temple in Los Angeles and kept their eyes on the hill in Oakland.

One of the war’s few favorable impacts was the acquisition of the longed-for Oakland site. Just two weeks after Pearl Harbor was bombed, A. B. Graham, a Latter-day Saint realtor who had been on the original site-selection committee, informed Oakland Stake president Hilton that because of the war, the owner of the hill was unable to obtain building materials to go forward with his planned subdivision. He offered the entire 14.5 acres to Graham for eighteen thousand dollars. President Hilton said: “This is most important. It is an answer to our prayers. We won’t wait for the mails. I will go directly to Salt Lake tonight.” [18]

The First Presidency agreed to look at the proposed site. One delay after another kept President David O. McKay from coming for nearly two months, so the staunch “hill watchers passed many anxious hours” as the owner was on the verge of selling the property to others who were offering him more money. Graham’s diplomacy was rewarded as the site was still available when President McKay finally arrived. He was “enraptured at what he saw” and promised to recommend its purchase. From that time on the Saints spiritedly referred to the site as “Temple Hill.” The purchase of this property was consummated by August 1943. [19]

Then followed the even more difficult task of obtaining an additional two acres, “which were absolutely necessary to provide the proper entrance to the tract itself.” The owners of the two acres were not interested in selling because it was “their country home and the place where they kept their precious horses.” A few years later, however, they finally agreed to sell the property—for six thousand dollars more than Church leaders in Salt Lake had authorized. Fearing that further delay might result in losing the strategic piece and lead to the entire project’s undoing, “local stake authorities counseled together, and concluded to buy the two acres on their own responsibility, knowing that time would justify their actions. They proposed to raise the extra six thousand dollars among themselves, if necessary, rather than risk losing the natural ‘key’ to the entire project.” [20]

The property was finally purchased in August 1947, after which the First Presidency informed the Oakland leaders that “we have concluded that you acted wisely and will accordingly advance the entire purchase price.” Subsequent purchases brought the site’s total size to 18.3 acres. Oakland leaders anticipated that this would be regarded as the “most impressive and inspiring location” of any temple site worldwide. [21]

The War Draws to a Close

During the closing years of the war, Saints in California were concerned about providing help to their fellow Saints—even those who were on the opposite side of the conflict. The Los Angeles Deseret Industries sent sixty thousand pounds of “first class salvage clothing and shoes” via the Panama Canal to Church members in Holland and Germany who had been devastated by the war. These, together with $6,100 worth of commodities sent by the Oakland Stake, were part of nearly four million pounds of goods supplied by the Church for relief in Europe.

In addition, in 1945 Deseret Industries trucks “collected and delivered to the U.S. government more than a hundred thousand pounds” of clothing in a national drive. The trucks visited 5,227 homes, 92 percent of which donated something. [22] Many of those supplies would be distributed in Europe immediately following the close of the war under the personal supervision of Elder Ezra Taft Benson of the Twelve.

As had been the case with Joseph F. Smith, Heber J. Grant’s service as president of the Church ended as a world war came to its close. President Grant died on 14 May 1945, just one week after Germany’s surrender and three months before Japan’s. Throughout his twenty-seven-year administration, he had encouraged the California Saints, and there had been substantial growth in the Golden State. Much of the state was blanketed by wards and branches. In fact, as the war drew to a close, approximately 10 percent of all Latter-day Saints lived in California—a figure that would remain fairly constant from that time forward.

Notes

[1] Eleanor Knowles, Howard W. Hunter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 70–71.

[2] Quoted in Susan Kamei Leung, How Firm a Foundation: Tiic Story of the Pasadena Stake (Pasadena, Calif.: Pasadena California Stake, 1994), 14.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eugene E. Campbell and Richard D. Poll, Hugh B. Brown: His Life and Thought (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1975), 144–46.

[5] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:484.

[6] In Conference Report, April 1942, 90–96.

[7] T. H. Watkins, California: An Illustrated History (Palo Alto, Calif.: American West, 1973), 434.

[8] Ibid., 435–36.

[9] Muir, 1:475.

[10] Watkins, 439.

[11] In Conference Report, April 1943, 128.

[12] Leung, 18.

[13] Knowles, 97–98; Leung, 21.

[14] Church News, 10 January 1981, 2, as quoted in Knowles, 101.

[15] Mission Annual Reports, 1941^42, 1944; LDS Church Archives.

[16] Muir, 1:475.

[17] Leung, 18–19.

[18] David W. Cummings, Triumph: Commemorating the Opening of the East Bay Interstake Center on Temple Hill, Oakland, January 1958 (Oakland: Oakland Area Stakes, 1959), 10.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid., 19.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Muir, 1:288–89.