Where Shall We “Gather”?

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State(Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 1–10.

Between two and three hundred men, women, and children lined the railing of the old sailing ship as it gently rocked and groaned its way through the Golden Gate. Eyes strained against an abundant fog that revealed, then hid, the bushcovered hills. As they approached a sandy beach, a dozen or so small, primitive buildings came into view. Not a very imposing place, most perhaps thought. But they were happy to see land again after nearly six months at sea. Many may have thought about comfortable homes left behind in New York City and other civilized East Coast locations. And they may have wondered how they would acclimate themselves to such a primitive place. The date was 31 July 1846, and most of these pilgrims, leaving behind forever their friends and families, had sold all they had in order to make the voyage.

These newcomers, California’s first large group of Anglo settlers, were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints, better known at the time as Mormons. They were making a religious pilgrimage to establish a new settlement in an unknown and largely unsettled these people, and what had brought them? An understanding of their East Coast origins and their belief in “gathering” helps answer these questions. location.

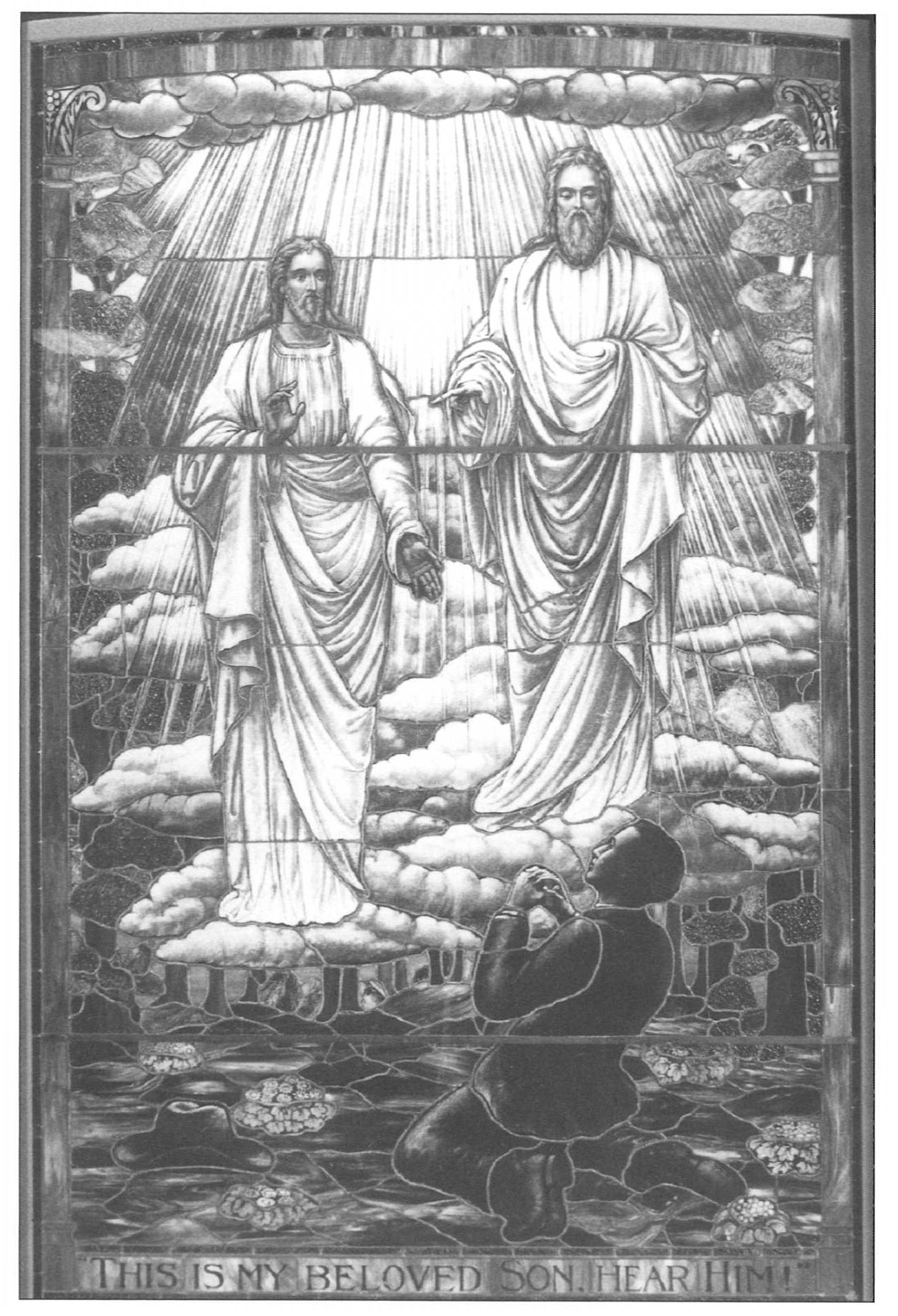

Their story began with Joseph Smith. As a boy, he was confused by conflicting religious perspectives during an unusually intense revival atmosphere near his home in western New York. [1] In the early spring of 1820, he, a fourteen-year-old who lacked knowledge but was full of youthful faith, sought guidance through prayer. He recorded that as he knelt in a grove of trees, God the Father and his Son, Jesus Christ, appeared to him in a glorious vision, assuring him that “the fulness of the gospel” would subsequently be made known to him and that through him the New Testament Church would be restored. [2]

Stained-glass window depicting the First Vision; formerly

in Los Angeles's Adams Ward chapel, now on display at the

Museum of Church History and Art in Salt Lake City

Joseph spent the next three years doing the ordinary tasks of frontier farming. In 1823, he was visited by another heavenly messenger. An angel, surrounded by brilliant light, identified himself as Moroni and told Joseph about the thousand-year history of a group of ancient American Christians. Moroni, the last prophet of their extinct civilization, had been entrusted with a history that his father, Mormon, had prepared on gold plates. Joseph Smith was called to translate the record and publish it to the world as the Book of Mormon, affirming that its prime objective was to convince “Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ” (Book of Mormon, Title Page).

With many of the first converts to his message present, Joseph Smith organized The Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints on 6 April 1830, the term Saints simply referring to Church members. [3] They were also called Mormons because of their belief in the Book of Mormon. Due to the extraordinary events that led to the Church’s organization, Latter-day Saints accepted Joseph Smith as a prophet and as God’s authorized spokesman. His successors, as presidents of the Church, have been likewise regarded (D&C 1:38).

Six months after the Church’s organization, Joseph Smith recorded a revelation directing the Saints to gather to a central location (D&C 29:8; 37:3). “Gathering” became an important theme throughout the history of the Latter-day Saints and was significant in bringing them to California’s shore.

From 1831 until 1838, Kirtland, a town in northeastern Ohio, was the main gathering place. The Church erected its first temple there. “Stakes” were established as gathering places in Missouri as well as in Ohio. The term stake was adopted from the writings of the Old Testament prophet Isaiah, who referred to stakes figuratively as supporting the tent of God which would cover and shelter his people (Isa. 54:2; see also D&C 115:5–6).

Such gatherings undoubtedly strengthened the young Church, which was made up of converts from diverse traditions. They were able to mingle together, to be fed spiritually, and to hear the Church’s doctrine accurately expounded through personal contact with their Prophet. However, gathering also brought adversity. Much of the Church’s intense persecution stemmed from earlier settlers who felt threatened by a sudden influx of people with different religious and social views; therefore, they endeavored to stop the “Mormons’” gatherings.

In 1838–39, the Saints were forced to flee from both Missouri and Ohio. Missouri’s governor, Lilburn W. Boggs, decreed that they either be exterminated or driven from his state. [4] Church pleas for redress from the federal government were ignored.

Fleeing to Illinois, the Latter– day Saints purchased land and began constructing another city. They named it Nauvoo, from a Hebrew word meaning ‘‘beautiful.” The area had been a swamp prior to their settlement, but soon the land was drained, and Nauvoo became one of Illinois’s largest cities as the growing Church gathered and began constructing a second temple.

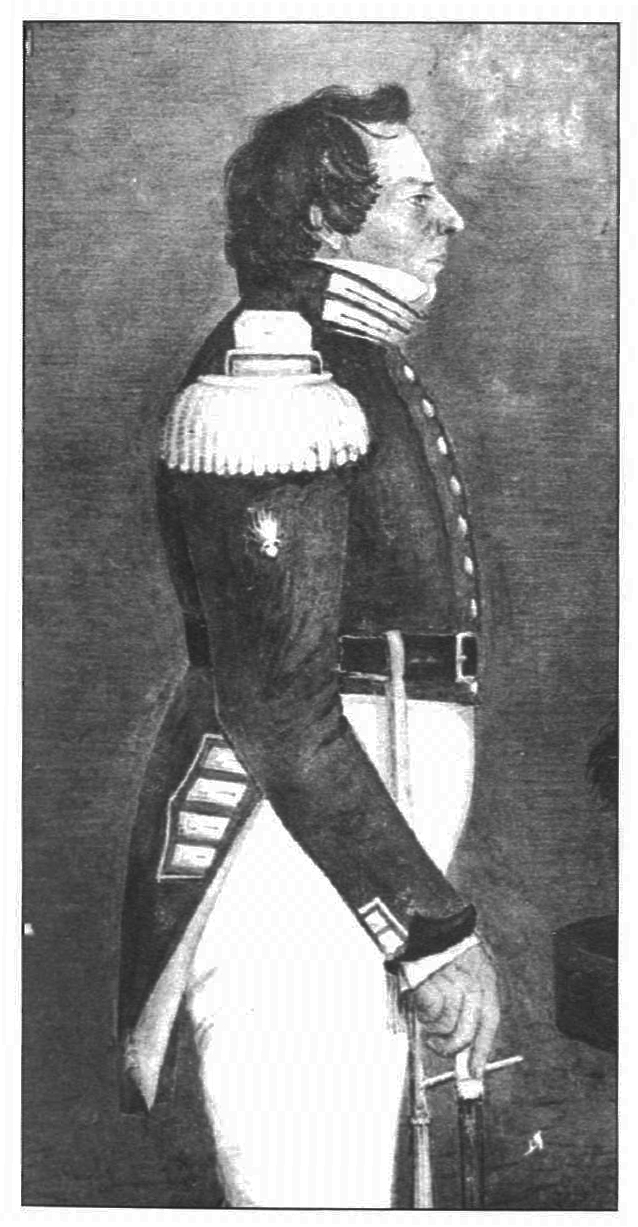

Joseph Smith in uniform of the Nauvoo Legion

California Considered

Soon it became apparent that permanent peace could not be achieved in Illinois either. After about four years, earlier residents and state officials began demanding that the Mormons move again. As mob pressures mounted, Church leaders became convinced that the Saints would once again need to flee for their lives. Where could they go? The Church gave much thought to this question. As early as 1831, while still in Ohio, Church members had spoken of going to the Rocky Mountains. [5]

Now, even as they built the city of Nauvoo, Joseph Smith looked forward to yet another haven for his people. In 1842 he declared that his followers would continue to be persecuted but that many would “build cities and see the Saints become a mighty people in the midst of the Rocky Mountains.” [6]

In 1844, as Nauvoo continued to grow, opposition increased. It was in this context that California was first specifically mentioned as a possible gathering place. On 20 February, Joseph Smith “instructed the Twelve Apostles to send out a delegation and investigate the locations of California and Oregon, and hunt out a good location, where we can remove to after the temple is completed, and where we can build a city in a day, and have a government of our own, get up into the mountains, where the devil cannot dig us out, and live in a healthful climate, where we can live as old as we have a mind to.” [7] At that time California was a rather ambiguous region encompassing much of what is now the western United States south of Oregon, from the Rockies to the Pacific.

Martyrdom and a New Leader

As some Illinois citizens became more resentful, a series of clashes culminated in the murder of Joseph Smith by a mob on 27 June 1844, leaving the Twelve Apostles to preside over the Church. [8] The enemies of the Saints speculated that the Prophet’s death would scatter the Church and break it up. Instead, the martyrdom became a rallying cry, and under the apostles, the Church flourished.

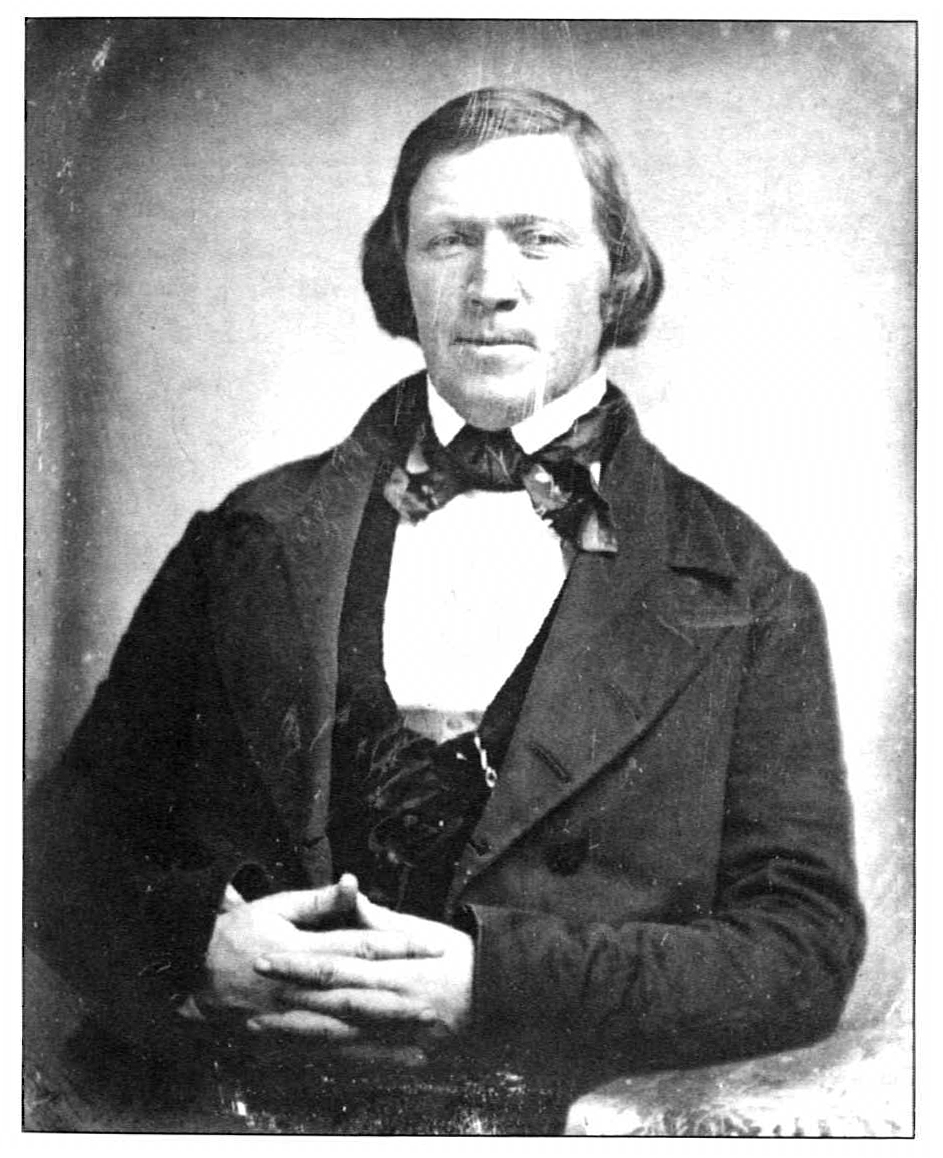

Although Brigham Young, president of the Twelve, had almost no formal schooling, he had developed great qualities of leadership which Joseph Smith recognized the first time they met. On that occasion the Prophet declared, “The time will come when brother Brigham Young will preside over this Church.” Becoming one of the original Twelve Apostles in 1835, Brigham Young demonstrated unwavering loyalty. This earned him the nickname “Lion of the Lord.” presided over the Church until his death in 1877, first as president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and after 1847 as president of the Church.

Brigham Young in 1850

Gathering Plans Solidified

After becoming the Church’s leader, President Young continued to examine various gathering options. On New Year’s Day in 1845, he recorded in his diary: “I met in council with my brethren of the Twelve. The subject of sending a company to California was further discussed.” [9] During the spring and summer of that year, published accounts of John C. Fremont’s western expeditions became available, and those positive reports were studied eagerly by leaders of the Church.

By August 1845 the idea of a central settlement in the Rocky Mountains, together with gathering places on the Pacific Coast, was fairly well established in the minds of President Young and other Church leaders. He wrote to Addison Pratt, who was serving a mission in the Pacific Islands:

If any of the brethren of the islands wish to emigrate to the continent here, then [have them] come to the mouth of [the] Colombia River in Oregon, or the Gulf of Monterry or St. Francisco, as we shall commence forming a settlement in that region during [the] next season and make arrangements with agents in each of those places so emigrants will be enabled to get all necessary directions, and provisions for going to the settlements. The settlement, will probably be in the neighborhood of LakeTampanagos [Utah Lake] as that is represented as a most delightful district and no settlement near there. [10]

Elder Parley P. Pratt of the Twelve (Addison’s distant relative) described the plan in a letter to a Church member in New Jersey: “I expect we shall stop near the Rocky Mountains about 800 miles nearer than the coast say 1,500 from here [Nauvoo] and there to make a stand until we are able to enlarge and to extend to the coast.” [11]

It was about this time that Latter-day Saints began singing lyrics penned by Elder John Taylor:

The Upper California. O! that’s the land for me,

It lies between the Mountains and great Pacific Sea. . . .

A land that blooms with endless spring,

Our tow’rs and temples there shall rise

Along the great Pacific Sea. [12]

Months of intense preparations culminated in the Saints’ exodus from Nauvoo early in 1846, followed by the epic westward trek across the Great Plains. Yet not all Latter-day Saints were part of this main body of overland immigrants. There was a substantial number in the northeastern United States, and Church leaders devised an alternate plan for their migration.

Notes

[1] See Whitney R. Cross, The Burned Over District (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1982); and Milton V. Backman Jr., Joseph Smith’s First Vision (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1971).

[2] History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 1:5, 4:536 (hereafter HC).

[3] Ibid., 1:74–80.

[4] Ibid., 3:175.

[5] Ronald W. Walker, “Seeking the ‘Remnant’: The Native American During the

Joseph Smith Period,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (spring 1993): 8–10.

[6] HC 5:85.

[7] HC 6:222, 224.

[8] “History of Brigham Young,” Millennial Star 25 (11 July 1863): 439.

[9] Preston Nibley, Brigham Young: The Man and His Work (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 63.

[10] Brigham Young to Addison Pratt, 28 August 1845, Brigham Young Papers; LDS Church Archives.

[11] Parley P. Pratt to Isaac Rogers, 6 September 1845, Parley P. Pratt Papers; LDS Church Archives.

[12] Quoted in J. Kenneth Davies, Mormon Cold: The Story of California’s Mormon Argonauts (Salt Lake City: Olympus, 1984), 4.