A Spiritual Wilderness: 1857–87

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 207–28.

Until the mid-1850s, Latter-day Saints in California seemed to prosper. Many enjoyed a measure of wealth from mining and other activities despite wild economic swings. Church congregations, small and large, dotted the state. No one would have imagined that within a few years Church activity in California would be almost completely extinguished.

Problems in Utah

In Utah, many of the Saints were experiencing hard times. There had been droughts and crop failures. Some Saints began to waver in their faith. Church leaders suggested that the loss of land, crops, and health were punishments for ingratitude and faithlessness and called for a thorough “Reformation.” As a result, some entire communities assembled to pray on their knees for forgiveness and better days.

At the same time, the Saints were being challenged by problems from without. They had chosen to settle the Utah desert primarily to avoid conflicts with their neighbors and to be left alone. Despite this, they rejoiced when their chosen land became part of the United States, even though Utah was granted territorial status rather than hoped-for statehood. But because Utah was a territory, its chief officers were federal appointees rather than Church members, and a war of words and wills resulted between them and the Saints.

For example, while Judge W. W. Drummond professed to be defending solid Puritan morals, he sometimes invited a prostitute, whom he had brought from the East, to sit with him on the judicial bench. Such behavior aroused the Saints’ indignation, and under pressure, Drummond resigned. Returning to Washington via California early in 1857, he vengefully accused the Latter-day Saints of rebellion against the U.S. government. In his official letter of resignation, Drummond charged them with destroying court records and asserted that “the Mormons look up to [Brigham Young], and to him alone, for the law by which they are to be governed: therefore no law of Congress is by them considered binding in any manner.” [1]

In the previous fall’s election, the newly formed Republican Party had promised to eradicate the “twin relics of barbarism”—slavery and polygamy. Now, President James Buchanan and the Democrats were anxious to show the nation that they, too, opposed LDS plural marriage. In a labyrinth of lies and deception, Drummond’s letter of resignation was “probably the most important factor in forming the Buchanan administration’s image of the Church.” [2]

Ironically, though the Church required the Saints to live with integrity, honor, and moral principles tied to sacred marriage vows, critics like Drummond used polygamy as an excuse to ridicule and persecute them but placed no such restrictions on themselves. This was particularly true in California, whose leading city was known for its numerous prostitutes, including Lola Montez, courtesan to European nobility and “special friend” to Samuel Brannan. Throughout California, the outcry grew ever more vociferous in condemning the Saints’ practice of plural marriage.

Without making any attempt to confirm the reliability of Drummond’s charges, President Buchanan decided to remove Brigham Young from his office as territorial governor and to send an army of twenty-five hundred men to assure the installation of a new governor. This force was as large as General Kearny’s Army of the West during the Mexican War a decade earlier. President Young vowed that no hostile army would drive the Saints from their homes again.

In this tense atmosphere, a disastrous tragedy occurred at Mountain Meadows in Southern Utah. On 11 September 1857, 120 emigrants from Arkansas, Missouri, and elsewhere were ambushed and killed by a group of angry Indians and overzealous Mormon settlers, perhaps in retaliation for earlier persecutions in Missouri and the recent murder of Parley P. Pratt in Arkansas. [3]

The nation’s presses, including some in California, began demanding Mormon blood. The San Francisco Bulletin announced: “Virtue, Christianity and decency require that the blood of the incestuous miscreants who have perpetrated this atrocity be broken up and dispersed. Once the general detestation and hatred pervading the whole country is given legal countenance and direction, a crusade will start against Utah which will crush out this beastly heresy forever.” [4]

As the U.S. Army approached Utah, the Saints organized a guerilla force to intercept and harass it in Wyoming. The marauders appeared out of nowhere, stampeded the army’s animals, blew up its ammunition, set fire to supply wagons, then disappeared again into the darkened prairie. Night after night they took their toll on the army’s provisions and nerves. Hungry, freezing, and embarrassed, the army was forced to make winter camp more than a hundred miles short of its objective.

A Call to Utah

In the fall of 1857, not knowing what the presumably hostile army would do, President Brigham Young called all missionaries who were abroad, as well as settlers in outlying colonies, to come to Utah and prepare to defend Zion. Following these instructions, various groups of Saints in California departed to join the main body of the Church in Utah. George Q. Cannon sent his family with a group of elders and remained a little longer to issue the last number of the Western Standard on 6 November 1857. Then, on 3 December, he and others from San Francisco joined “Orson Pratt, Ezra T. Benson, and other elders having arrived from England en route for the Valley,” where they planned “to take part in the defence of [their] liberties and homes.” [5]

By 2 November, Brigham Young advised the San Bernardino stake president to “forward the Saints to the valleys as soon as possible in wisdom.” [6] The following February, Ebenezer Hanks sold the Rancho, paying off the mortgage with a little left over. With Elder Cannon’s departure and the Rancho sold, “the official efforts on the part of the Church to maintain an organization within the state of California came to an end.” [7]

Estimates of the number of California Saints who headed to Utah run as high as three thousand. Disproving the concerns of some that these Saints were “lukewarm,” many loaded all their possessions into wagons and made the long, difficult journey to Utah to fight and, if necessary, die for the kingdom. They willingly gave up everything from their years of labor and returned empty-handed. “The faithful gave up their homes, their farms, their businesses, obliged to sell out for a pittance; those who wanted to acquire the Mormon lands and buildings had only to wait a few days to take possession without any cost at all.” [8]

Henry Boyle, former Battalion soldier and one of the more successful California missionaries, reported that the faithful Saints in San Bernardino were “selling out, or rather Sacrificing their property to their enemies. . . . The apostates and mobocrats are prowling around trying to raise a row.” He wrote in his diary that the Saints’ enemies were “trying to stir up the people to blood shed & every wicked thing.” The situation became desperate: “O, is it not Hell to live in the midst of such spirits? They first thirst for & covet our property, our goods, & our chatels, then they thirst for our blood. . . . I think I shall feel like I had been released from Hell when I shall have got away from here.” [9]

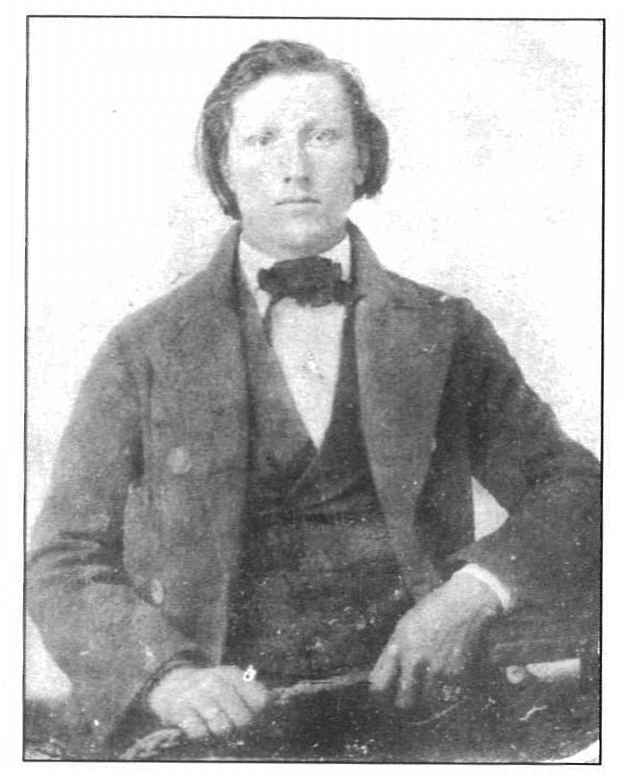

Joseph F. Smith, now a nineteen-year-old returning from his mission in Hawaii, joined some of the San Bernardino Saints heading for Utah. After they went a short distance and made camp, a group of drunken men approached, cursing and threatening to kill any Mormons they could find. Most of the Latter-day Saints, fearing for their lives, quickly hid in some brush along a nearby creek.

Elder Smith was just returning to the camp with an armload of firewood. “I dared not run,” he later recalled, “though I trembled for fear which I dared not show. I therefore walked right up to the camp fire and arrived there just a minute or two before the drunken desperado, who came directly toward me, and, swinging his revolver in my face, with an oath cried out: ‘Are you a———Mormon?’” Looking him straight in the eyes, Joseph’s disarming reply was, “Yes, siree; dyed in the wool; true blue, through and through.” Lowering his weapon and extending his right hand, the drunken man responded, “Well, you are the———pleasantest man I ever met! Shake. I am glad to see a fellow stand for his convictions.” [10]

Joseph F. Smith at age 19

Joseph F. Smith at age 19

Many of the San Bernardino Saints settled in Southern Utah near Beaver and Parowan. Not all of the California Saints relocated to Utah, however. Of the estimated 20–50 percent who did not move, most were or became disaffected. Henry Bigler, who returned to Utah from a Pacific Islands mission in 1858, reported that the majority of his contacts in California did not wish to join the Saints in Utah for one of three reasons: some were upset over the Church’s now-public practice of plural marriage; some did not wish to leave California’s mild climate for a place where, as one settler commented, he would have “to wade up to my neck in snow in order to get a little fire-wood”; [11] still others did not wish to be subject to Brigham Young's "high-handed authoritarianism." [12]

Jefferson Hunt, the respected pathfinder, lawmaker, and state leader, was one of the last to leave San Bernardino in early 1858. His three daughters, however, chose to remain behind. His son John returned to San Bernardino in 1859 but took his family back to Utah four years later. [13]

An aging Addison Pratt and his family were also torn apart, as expressed in a letter written by his daughter, Ellen:

Father has an aversion to a cold climate now he is getting in years. . . . He dreads . . . making another beginning in such a hard place; that is the most disagreement he and mother have. . . . She tries every way to encourage Father about going there . . . but he thinks he cannot go: he loves the Sea air, and wants to live where he can feel it; it makes him look so vigorous and youthful: he is scarcely like the same man. Mother has better courage to live in a hard place. . . . She has great zeal for this cause. . . . Should I believe one quarter of what I hear about the doings up there [in Salt Lake City] I should never dare to come there in my life; but I am not afraid, I shall go when mother does, as sure as you live. [14]

Addison Pratt decided he would stay in California, knowing that if he chose Utah there would be problems with his health, and if he chose California, there would be problems with his marriage. This faithful missionary who had already left home and family four times for island missions and who once felt that his first mission’s “exile for Christ’s sake” was “penance sufficient with good behavior the rest of my days, to secure me an interest in his kingdom,” resolved to stay in California even though his wife resolved to go.

He accompanied her into the Mojave Desert, where he made “every humiliating and condescending proposition, that the case demanded.” But she only treated his need to stay with contempt and disdain. There on the desert they parted. “I looked at her, & thought then . . . ‘that we had parted forever.’” [15]

The “Utah War” ended peacefully. Following counsel by the Saints’ old friend, Col. Thomas L. Kane, in the spring of 1858 President Young allowed two federal officials and the new territorial governor into Salt Lake City without military escort to inspect the court records, which were found to be intact.

Once the truth was discovered and a report made to Congress, the press did an about-face and insistently asked why taxpayers’ money had been spent on so foolish an army expedition. A truce was finally signed, and the army entered the Salt Lake Valley peacefully. However, to make sure they understood he meant business, President Young had every dwelling piled with straw and a sentinel at each to strike a match at the least army provocation. Col. Philip St. George Cooke, who had developed respect and fondness for his Mormon Battalion volunteers, was part of the expedition and passed through the city with his head bared and his military hat over his left breast in a reverent salute. [16] The soldiers were then peaceably quartered a good distance away from Salt Lake City, where they remained until 1861.

In 1863, Louisa Pratt visited her family that had remained in California and persuaded Addison to return to Utah with her. Upon their arrival, they chanced upon a traveling party that included President Brigham Young. “Brothers Young and Kimball alighted from their carriages and came to ours, and saluted Brother Pratt in the cordial manner, congratulating me on my success in having been to California, and returning brought my husband with me. They blessed us in the name of the Lord.” [17]

However, as he had suspected, Addison suffered terribly through two Utah winters before returning ill to the coast, where he made a final home for himself with his daughter in Anaheim. He died there on 14 October 1872, still full of faith and loyal to his Church. He was buried in the Anaheim cemetery.

The LDS Remnant in California

As the crisis in Utah passed, many of the families from San Bernardino began returning to California. By 1860, the Saints again formed a majority of the San Bernardino community.

One of those returning was David Seely, the original San Bernardino stake president. After moving to Utah, he had a disagreement with Brigham Young, who told him he might just as well go back to California. [18] Seely was dropped from the Church and remained in California looking after his timbering interests. Although more than half of the original San Bernardino colonists remained in or returned to California, none of their leaders were ever replaced, and no official Church organizations were ever reconstituted. Even without spiritual leadership, many retained their faith. Others lost their unique LDS identity, joining mainline churches or drifting away from religion altogether. Still others remained believers in the restored gospel and the mission of Joseph Smith but rejected Brigham Young and polygamy; most of those found their way into the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Where there had once been flourishing LDS congregations, RLDS groups now appeared. The San Bernardino Branch became the largest RLDS congregation in the West. [19]

Returning in 1864 from a mission to Hawaii, John R. Young discovered only a handful of still-faithful members in California. Notable among those few was John Horner, who related the story of his conversion. He said that

when he was a boy the Prophet Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdrey had called upon the Horner family. John M. wanted to visit with the young prophet, but his father insisted that he finish hoeing a piece of corn given him as a stint. Joseph, on learning of it, took off his coat and asked for a hoe and helped finish the task. As a result Horner was baptized by Oliver Cowdrey and confirmed by Joseph Smith, who predicted that the earth should yield abundantly at Bro. Horner’s behest.

By the time of John Young’s visit, Horner had paid some twenty thousand dollars tithing on his agricultural profits. [20]

He remained in California until 1879 when he moved to Hawaii to live out his last days. Upon journeying to San Bernardino, Young found only a few Saints and no organization. The family of Col. Alden Jackson was among the faithful, and Young spent the winter with them. During his stay he convinced the family to relocate to Utah and even drove one of their teams in order to pay his way to Salt Lake. [21]

When Porter Rockwell was recruited as a guide to escort Lt. Col. Edward Steptoe from the Great Basin to California, he visited acquaintances in the gold country. One of these was Agnes Pickett, the widow of the Prophet Joseph Smith’s brother, Don Carlos. She was recovering from a bout with typhoid fever which had caused her to lose all her hair.

Rockwell, who had long been a close friend of the Smith family, knew that to both him and Agnes, hair was worth more than its intrinsic value. Like the biblical Samson, he had received prophetic promises contingent upon never cutting his hair; like Samson, he attributed his successes to it. But because he had nothing else to relieve her embarrassment, “he had his hair cut to make her a wig and from that time he said that he could not control the desire for strong drink, nor the habit of swearing.” [22] However, Rockwell, despite his cut hair, lived a long life and died a peaceful death in his bed in Utah.

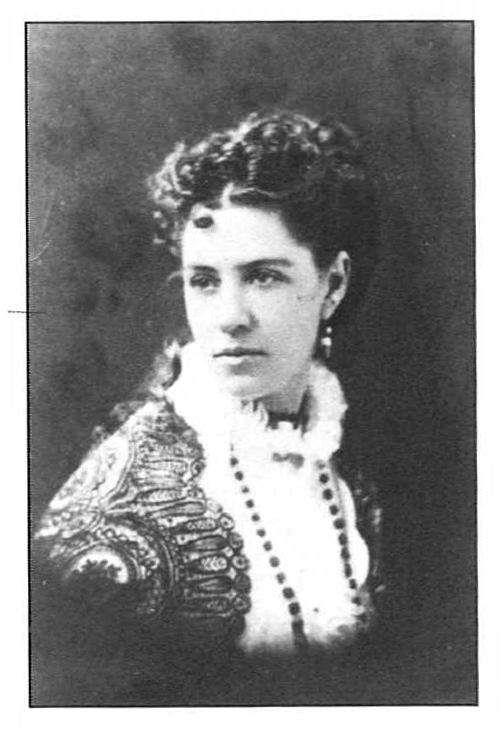

Agnes’s daughter, Josephine Donna Smith (named after her uncle, Joseph, and her father, Don Carlos), was a gifted poet who was about eleven years old when her family came to California. After a tragic marriage and divorce in Los Angeles, she moved with her mother and stepfather to the San Francisco area and remained there, unmarried, for the rest of her life.

She took as her pen name a shortened version of her own given names (Ina), and her mother’s maiden name (Coolbrith), becoming Ina Coolbrith. Just twenty years old when she moved to San Francisco, she was welcomed in local literary circles, her verse having been widely published already. Yielding to the demands of her stepfather, she did not identify herself as a Latter-day Saint. Still, her spiritual sensitivity is reflected in “this simple creed: ‘Love thou thy God; thy neighbor as thyself; Forgive, as thou dost hope to be forgiven!’ and lo! we have sweet Heaven about us on the earth.” [23] A half-century later she was named “Poet Laureate” of California.

Ina Coolbrith

Ina Coolbrith

Coolbrith became a key factor in creating California’s “Golden Age” in literature. She was closely acquainted with and influenced such illustrious writers as Bret Harte, Charles Warren Stoddard, Mark Twain, Henry George, Prentiss Mulford, Jack London, and Joaquin Miller. Jack London, remembering her as an invariably kind and gentle Oakland librarian who had befriended him and had opened the world of literature to him when he was little more than a street waif, called her his “literary mother.” She never wrote an autobiography, although friends urged her to do so. She laughingly replied: “Were I to write what I know, the book would be too sensational to print; but were I to write what I think proper it would be too dull to read.” [24]

Some other notable Latter-day Saints remaining in California were members of the Garlick family. Aaron and Mary Garlick were young British converts who came west by wagon, passing through Utah and going on to California in the spring of 1857, just before the Saints were asked to abandon the Golden State. Mary was pregnant, and both she and Aaron were too exhausted and poor to go back, so they lived out of their wagon for a year, where their eldest son was born. By the time they had sufficient strength and means, the Utah crisis had passed. They bought a home at 108 2nd Street in Sacramento, where they remained for many years as the focal point of an on-again, off-again LDS branch. They became prosperous and respected Sacramento citizens.

Aaron joined the Reorganized Church, where he served diligently and even held the position of branch president. Some time in 1870, however, Garlick “discovered his mistake, and relinquished the presidency, priesthood and membership in that organization” and asked to be rebaptized a Latter-day Saint. [25]

Brooklyn Saint Thomas Eager, an Alameda County supervisor, proposed in 1856 that the communities of Clinton and San Antonio Redwoods, where he had resided since entering the lumber business in 1849, be combined into a town called “Brooklyn” in memory of the ship that had brought him to California. Eager continued his public service as a member of the California state legislature from 1861 to 1869, during which he served a term as sergeant at arms. His town bore the Brooklyn name until 1872, when it was annexed to Oakland and became that city’s Seventh Ward.

A former private in Mormon Battalion Company E, Daniel Brown remained in Watsonville with his mother, Mary A. Brown, and is buried there with her in the Pioneer Cemetery.

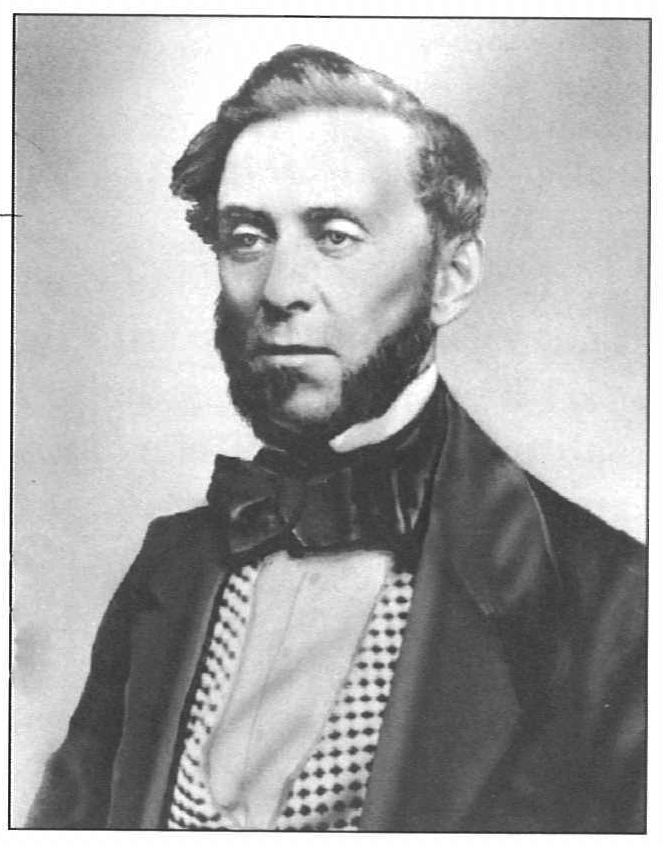

Samuel Brannan’s Fortunes

Undoubtedly the best known of the Latter-day Saints—or former Latter-day Saints—who remained in California was Samuel Brannan. In 1853, two years after he had cleaned up San Francisco with his Vigilance Committee and was disfellowshipped from the Church, Brannan was elected to represent California’s most important city in the state senate. He claimed he would refuse to serve but was elected over his objections as a write-in candidate. However, when he went to the East on business, he was replaced. Before he left, he agreed to reorganize the prestigious California Society of Pioneers, which he had helped found, and he served a term as its president.

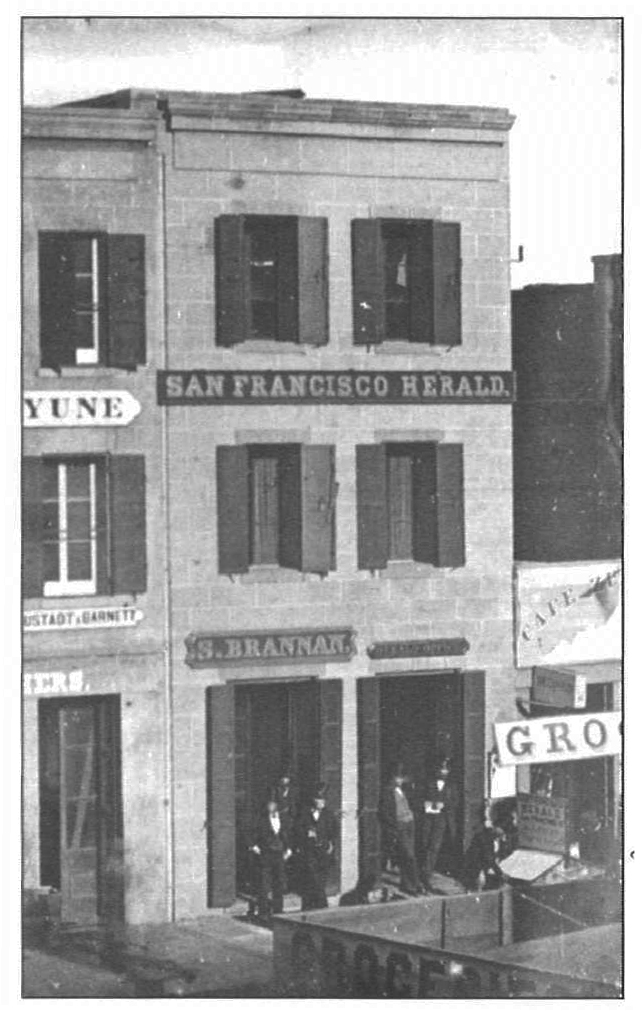

Samuel Brannan

Samuel Brannan

According to a family tradition, on that trip he visited his first wife, Harriet, and their daughter, Almira, and brought them to California at his expense with the understanding that they would not reveal their identities. In 1855, soon after their arrival, “Hattie” went to Los Angeles and obtained a divorce. [26]

Later, when Brannan was at the height of his wealth and fame, he and his wife, Eliza, went to Europe, where their reputation as California millionaires preceded them. Brannan bought sheep and vines to export to California. Although he returned, Eliza insisted on staying in Europe and educating their children there.

On 21 October 1857, as George Q. Cannon prepared the last issue of the Western Standard and most Latter-day Saints readied to leave the state, Brannan opened his bank at the northeast corner of Montgomery and California Streets. One of his biographers asserts that he was “the acknowledged financial leader of the city and the titan to whom all other businessmen deferred.” [27]

Brannan's newspaper office

Brannan's newspaper office

It was the practice of the time for large banks and other financial institutions to issue their own currencies, which Brannan’s bank did. During the 1860s, while the United States was embroiled in a civil war, many people preferred Brannan’s currency to that of the federal government. [28]

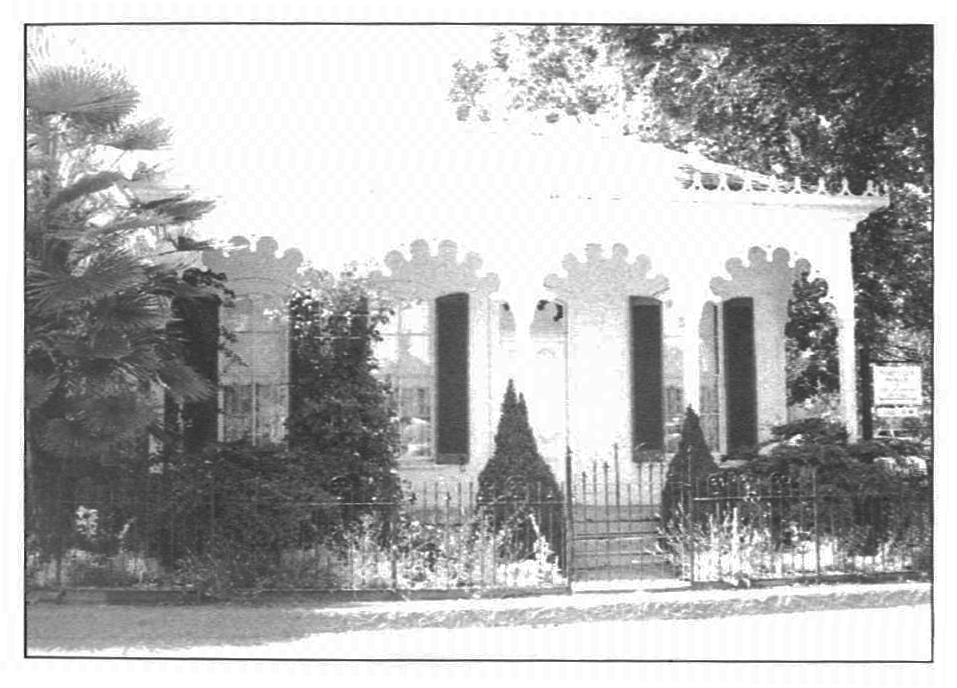

Brannan also began developing a large, mile-square resort north of San Francisco for which he coined the name “Calistoga.” The resort contained a hotel, avenues lined with palms and thirty cabins, a roller-skating rink, a natural hot-springs pool, a reservoir of clear mountain drinking water (pure spring water is still bottled and sold under the Calistoga label today), horse barns, trails, and a racetrack. [29]

One of Brannan's guest cottages in Calistoga

One of Brannan's guest cottages in Calistoga

For ten years after the Saints’ departure from California, Brannan rode the crest of business success. In 1868, at age forty-nine, he was part of an investment group that bought nearly 180,000 acres of what is now Los Angeles. But that year his empire began to crumble.

Brannan invested $125,000 in Hawaiian land and had to sell for $45,000. He became increasingly incapacitated by alcohol when his temperate brother, who had been a steadying influence in his life, died. [30]

On top of these difficulties, a band of disgruntled workmen took possession of a sawmill they had been building for him at Calistoga. Accompanied by a force he had organized, Brannan advanced on the mill one bright, moonlit night. When the workmen ordered them to halt or be shot, the force fled, but the irate Brannan, impetuous and headstrong, continued to advance alone. A volley was discharged from inside the mill, and Brannan fell, riddled with bullets. About thirty bullets either pierced his clothing or penetrated his body. Though some were surgically removed, he was left a cripple, walking with a cane the rest of his life.

In 1870 Eliza returned from Europe with their grown children and sued for divorce. She demanded half their property in cash, forcing him to liquidate his assets at disastrously low prices. [31]

In 1878 Brannan went to Mexico City to press the Mexican government for repayment of the nearly $80,000 he had lent them to finance a hundred-man army in their war against France. They only sneered at him and gave him a huge tract of Sonora, but no cash. Unknown to him, the land was also claimed by a fierce tribe of Yaqui Indians, making it unusable for Brannan. He lost heavily not only in that venture, but also on every other investment he made during the depressed 1870s and outside his beloved California.

Having moved to Guaymas on the Gulf of California in 1882, at age sixty-three Brannan married an attractive thirty-one-year-old daughter of “a prominent Mexican family.” [32] The following year, the Deseret News, the Church’s newspaper in Salt Lake City, published a description of a slovenly Brannan submitted by three men who had just visited Brannan in Mexico: “He was partially paralyzed, in the depths of poverty, residing in a little shanty, friendless, and living in the most groveling forms of vice. . . . He was half naked and filthy, a pitiable spectacle to behold.” [33] A reader who read the sordid description regarded these circumstances as a fulfillment of prophecy: “In 1854, while the late Parley P. Pratt was on a mission on the Pacific Coast, he was informed that Mr. Brannan, then a millionaire, was very much afraid some one would kill him for his money. Parley P. Pratt said: ‘Go, tell Sam Brannan from me that he shall not die till he is in want of ten cents to buy a loaf of bread.’” [34]

When Brannan learned about these articles, he vigorously refuted them:

With regards to the prophesy of Parley P. Pratt, as printed in the Deseret News sometime since, that I would die a pauper—I don’t believe he ever uttered it. If so, he must have been drunk or crazy. . . . The whole yarn is a pure fabrication of their own.

I can hardly consider my circumstances extremely desperate; and not withstanding they reported I was living in a “dug out.” I own ten lots and two houses here, all rented at good rates. My wife also owns a large double house and lot from which she derives a nice little revenue; and we board with her daughter. [35]

However, Brannan’s fortunes took another turn for the worse. Four years later, after his Mexican wife left him, he sold pencils on the streets of Nogales. He then returned to San Francisco, where he is said to have slept on a bench on a street he once owned, in front of a hotel he once owned, now unable to pay twenty-five cents for a room. [36] He visited the hall of honors at the California Society of Pioneers, stood in front of a portrait of himself as a young, handsome, powerful man, and wept. [37] He was asked by the California historian, Hubert H. Bancroft, to provide an account of his life’s experiences. However, the cold weather inflamed his old wounds, and he soon left for the warmer San Diego environment, where his tent house and historical manuscript were washed away in a flood.

At the bidding of Brannan’s nephew, the Odd Fellows lodge, which Brannan had founded and financed, gave him a small monthly stipend. This allowed him to move into an apartment and hire a cleaning lady to help out each week.

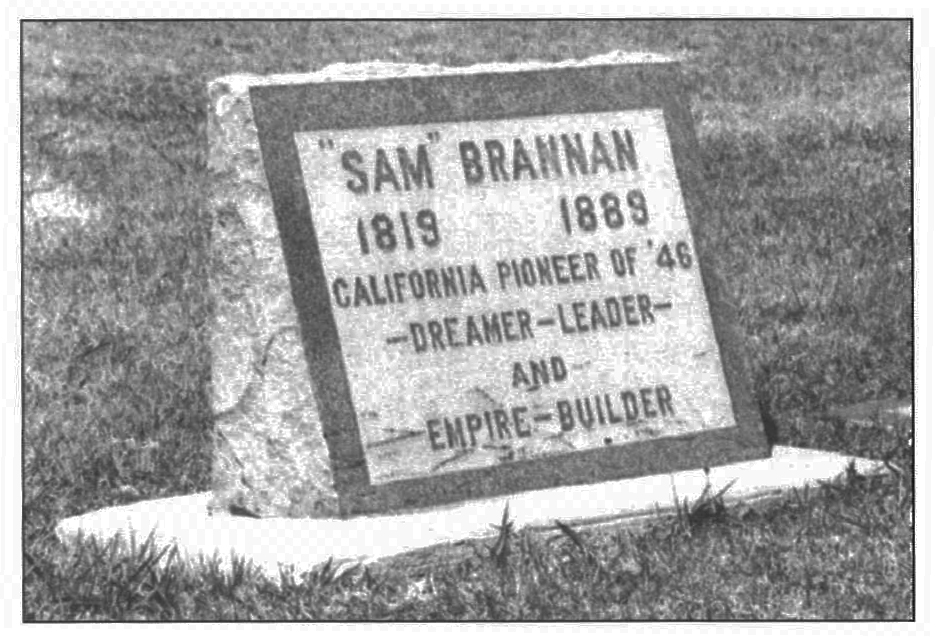

Finally, in May 1889, just two months after his seventieth birthday, Brannan, isolated in his San Diego apartment, died of inflammation of the bowels. [38] There was no funeral, nor family or friends, to mourn his death or to memorialize his accomplishments. His remains lay unclaimed in a public vault for sixteen months before his nephew, Alexander Badlam Jr., arranged for a proper burial. As President Brigham Young had prophesied forty years before, there was, in the end, “no arm to save” the man once so highly esteemed by some of the nation’s best and brightest. [39]

Samuel Brannan was indeed a paradox. One biographer summed up his life as follows: “‘No penniless stranger seeking provisions or goods ever left his store without being supplied.’ And it was true. Sam, who robbed with one hand his brothers in religion, his old friend Sutter, and others, helped with the other any needy stranger who presented himself.” [40]

Brannan was buried in San Diego’s Mount Hope Cemetery with only a plain wooden stake marking his grave. In 1926, someone provided a granite marker.

Samuel Brannan's grave in San Diego

Samuel Brannan's grave in San Diego

The Church Comes Out of the Wilderness

During the 1870s, tentative steps were taken to reestablish the Church in California. During the fall of 1871, when Elder Philip Leuba was on his way as a missionary from Salt Lake City to his native Switzerland, he met the Garlick family during a stopover in Sacramento. On 29 October, at Aaron Garlick’s request, Leuba rebaptized him a member of the Church and also ordained him to the office of elder. His wife and their two sons were also baptized. On 5 November, Leuba appointed Garlick to preside over the branch which at that time consisted of only six members. In April 1873 Garlick wrote to Brigham Young “inviting all travelling missionaries who came through Sacramento to call on the little branch.” [41]

The next known attempt at reorganizing the Church in California was made in 1876. Job Taylor Smith, an Ogden businessman going to California for his health, was called to “take a mission to the Pacific States.” Leaving for California by train on Christmas Day, he was startled by a man who verbally attacked the Latter-day Saints “in a very malignant manner . . . but fortunately he kept his hands off. The passengers on the car were all disposed to hear the Mormons abused, and seemed to enjoy the scene.” Arriving in Sacramento on 27 December, Smith was “hospitably received and lodged at Aaron Garlick’s” and found a “small branch of the church numbering about 12 persons in good standing.” [42] Within four years the branch would grow to twenty members.

In January 1877 while Smith was still in Sacramento, California newspapers widely covered the execution of John D. Lee for his role in the Mountain Meadows Massacre twenty years before. The newspapers also accused Brigham Young of being primarily responsible for the tragedy. Deeply affected by these attacks, Job Smith climbed to the top of the state capitol, where he knelt and prayed that God would “bless the cause of Zion . . . when the Legislatures of this State, or any other body of men, shall in this State House, design, plot, discuss or enact measures for the injury, downfall or disadvantage of thy Saints. . . . May confusion enter into their counsels until they suffer defeat.” [43]

On 15 January 1877, Elder Smith visited Brooklyn passenger William Atherton and his wife at their home in Oakland. They had joined the Reorganized Church, but Smith rebaptized them in the San Francisco Bay. On 4 March, Atherton was “appointed by unanimous consent to preside over the Saints in Oakland.” [44]

Smith noted that most people in the area “revile the Mormons because of having a plurality of wives, and suppose them to be the most corrupt people upon the earth.” Nevertheless, Brigham Young, who still had not given up on San Francisco, instructed Elder Smith: “We shall be glad to have you organize the branch of the church in San Francisco. We should have a place there.” On 6 April, Smith helped organize a local branch of the Relief Society. Later that month he returned home to Ogden. [45]

That same year, three months before Brigham Young’s death, the First Presidency wrote to Smith: “You are hereby appointed to take charge of and preside over the mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, to assign the elders who may accompany you and others who may be called to labor with you in the ministry there . . . [and] to organize branches and conferences.” The First Presidency also instructed him to “secure a tract of land” where the Saints could gather and live according to the principles of the cooperative “United Order.” He was further instructed to investigate the profitability of raising crops and of cultivating willows for basket weaving. “Should you cultivate the grape,” the letter continued, “do not enter into the manufacture of wine, but cultivate the raisin grape.” [46]

Smith accordingly returned to California, where he organized the Oakland Saints into a cooperative. “By putting their means together,” they attempted to operate a boarding house, green grocery, and chair caning business. However, partly because the branch had only sixteen or eighteen scattered members, some of them blind and others “more or less unemployed,” the branch soon fell apart. The dissolution was “amicably accomplished” in November, and Elder Smith, “having received an honorable release,” returned home. [47]

The trickle of Latter-day Saints leaving Utah to make homes in California increased during the 1880s, partly because of the growing persecution in Utah of those practicing plural marriage and partly because of a “land boom” in California that rivaled the gold rush.

The passage of the Edmunds Act in 1882 intensified the anti-polygamy campaign. The first prosecutions began almost immediately with stiff prison terms handed out to convicted male violators. Dozens of federal marshals posed as census takers or peddlers, bribed children to get information about their parents, spied through windows, and in various other ways sought to apprehend polygamists. While working as a night watchman in the Church Tithing Office, Joseph W. McMurrin, who would later figure prominently in California LDS history, was shot and seriously wounded by one of those marshals.

Several husbands, often in jeopardy of being arrested, went into hiding on the “underground.” Among them were the entire First Presidency—President John Taylor and his two counselors, George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith. Rewards were offered for information leading to the arrest of those accused of polygamy. When a bounty of five hundred dollars was placed on President Cannon’s head, he was apprehended on a San Francisco-bound train, returned to Utah, and sentenced to prison.

With husbands and fathers in prison or in hiding, it was probably the women and children who suffered most from what they called “The Raid,” as they were left alone without means of support. In order to avoid these problems, many individuals and families fled to outlying areas—including California—where they became the nuclei around which the Church subsequently grew.

Though Utah had already recognized the right of women to vote, in February 1887 Congress tightened their grasp on the Saints with the Edmunds-Tucker Bill, which abolished women’s suffrage in Utah. The new law also required residents to swear, prior to being given the right to vote, that they were not polygamists and provided for the confiscation of the Church’s assets, even including Temple Square in Salt Lake City. Later that year, President Taylor died, a polygamist in exile.

Sixty years after the Church was founded, hostile forces now seemed to prevail. The Church as an institution was left without legal charter or monetary assets. Once again, the Saints stood vulnerable to the actions of a government whose Constitution guaranteed religious liberty. Forty years earlier California gold had helped save the Saints. Now, again, they turned to their Pacific neighbor for assistance.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Andrew Love Neff, History of Utah, 1847–1868 (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), 448.

[2] James 13. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 297–98.

[3] Allen and Leonard, 303–6; see also Juanita Brooks, The Mountain Meadows Massacre (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962).

[4] San Francisco Bulletin, 12 October 1857.

[5] George Q. Cannon, Writings from the WESTERN STANDARD Published in San Francisco, California (Liverpool: George Q. Cannon, 1864), ix.

[6] Eugene E. Campbell, “A Mistory of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 220.

[7] Ibid., 275.

[8] Irving Stone, Men to Match My Mountains (New York: Berkeley Books, 1982), 224–25.

[9] Henry G. Boyle Diary, 16 and 17 November and 4 December 1857; typescript, Brigham Young University Archives.

[10] Joseph F. Smith, Gospel Doctrine: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Joseph F. Smith, comp. Joseph Fielding Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1978), 532.

[11] Henry W. Bigler, Book G, quoted in Campbell, 280.

[12] Ibid., 282.

[13] Pauline Udall Smith, Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion (Salt Lake City: The Nicholas G. Morgan Sr. Foundation, 1958), 196, 229, 233, 238.

[14] Quoted in The Journals of Addison Pratt, ed. S. George Ellsworth (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 510–11.

[15] Ibid., 513–16.

[16] Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850–1859 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1960), 201–2.

[17] Louisa Barnes Pratt, Mormondom’s First Woman Missionary: Life Story and ‘travels Told in Her Own Words, ed. Kate 13. Carter (Utah: Nettie Hunt Rencher, 1950), 352.

[18] Campbell, 282–83.

[19] J. Kenneth Davies, Mormon Gold: The Story of California’s Mormon Argonauts (Salt Lake City: Olympus, 1984), 315.

[20] “Journal History of the San Bernardino Mission,” 5 December 1864, quoted in Campbell, 290–91.

[21] Ibid., 291–92.

[22] Harold Schindler, Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1966), 224.

[23] Josephine DeWitt Rhodehamel and Raymund Francis Wood, Ina Coolbrith: Librarian and Laureate of California (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1973), 374.

[24] Annaleonc D. Patton, California Mormons by Sail and Trail (Salt Lake City: Desert Book, 1961), 152.

[25] Philip Leuba to Deseret News, 6 February 1896, quoted in Campbell, 294.

[26] Reva Scott, Samuel Brannan and the Golden Fleece (New York: Macmillan, 1944), 331–34, 361–62. See n. 5 in chapter 2.

[27] Ibid., 376.

[28] Paul Bailey, Sam Brannan and the California Mormons (Los Angeles: Westernlore, 1943), 216–17.

[29] Today in the town of Calistoga, the Sharpsteen Museum preserves a diorama of the resort, together with one of Brannan’s original cabins.

[30] Bailey, 224–25.

[31] Ibid., 227.

[32] Samuel Brannan, “A Biographical Sketch Based on Dictation/’ 12, MS, C–D 805; Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

[33] Deseret News, 27 February 1883.

[34] Ibid., 8 March 1883.

[35] Salt Lake Tribune, 31 May 1883.

[36] Scott, 438–39.

[37] San Francisco Bulletin, 20 May 1916, 1.

[38] Scott, 441.

[39] Journal History, 5 April 1849; LDS Church Archives.

[40] Scott, 235.

[41] Campbell, 292–95.

[42] Job Smith Diary.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Quoted in ibid.

[47] Ibid.