The San Bernardino Colony: 1851–57

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 167–84.

Between 1848 and 1852, discussions among Church leaders concerning California typically centered on gold and its implications for the Saints. However, as the supply of this precious metal diminished, the focus regarding California shifted. Between 1850 and 1857, the Church’s energies were directed to promoting missionary work throughout the Pacific Coast, with headquarters in San Francisco, and to establishing a colony in the southern part of the state.

Plans for a Southern California Colony

Hope had glimmered regarding a Southern California LDS gathering place for four years—ever since Captain Jefferson Hunt (in May 1847) had described to Brigham Young the beauty and fertility of Isaac Williams’s Rancho Santa Ana de Chino, where a contingent of the Battalion had served: “We have a very good offer to purchase a large valley, sufficient to support 50,000 families.... We may have the land and stock consisting of eight thousand head of cattle, the increase of which was three thousand last year, and an immense quantity of horses, by paying 500 dollars down, and taking our time to pay the remainder/’ [1] The owner, Isaac Williams, was anAmerican who had married into the Spanish-California aristocracy. He had repeatedly offered his property to the Church, with attractive terms, as the various Latter-day Saint caravans stopped there for respite.

By 1849, Church leaders contemplated the advantages of having immigrant converts—even some from Europe—come to Southern California by sea and then settle there or travel overland to the Great Basin. To this end, the First Presidency, in late September, instructed Elder Amasa M. Lyman “to obtain all the knowledge he could in relation to good locations for a chain of settlements from G.S.L. City to the Pacific Coast.” [2] In response, Elder Lyman took with him “Brothers Hunter, Crismond, and Clift” to ascertain “the practicability of making a settlement of our people in the lower district.” He traveled to Los Angeles hoping to intercept the newly arriving Elder Charles C. Rich. Later that year, Elders Lyman and Rich determined to make a settlement in Southern California and launched efforts to purchase land. [3]

In November 1849 a party of fifty, headed by Elder Parley P. Pratt, was sent to explore and recommend future colonization sites along what came to be known as the “Mormon Corridor.” [4] Having explored as far as present-day southwestern Utah, the group’s recommendations were heeded. The Church began sending out organized parties to colonize virtually all the suggested Utah sites. Still, Church leaders felt the need to complete the corridor by establishing settlements at strategic locations all the way to the West Coast.

Thus, when Elders Lyman and Rich returned home from their California missions, discussions about the various Southern California sites were already well under way. There seemed to be agreement with President Young that a change of focus from gold to agriculture and other pursuits would be appropriate. Since Church leaders had consistently maintained that Saints should settle in California as well as Utah, Elder Lyman began meeting with those interested in migration to the West Coast. He approached several men who had previously been in California, including Brooklyn Saints and Battalion veterans, to help him plan a settlement in Southern California. Among those approached were William Glover and Albert Thurber, neither of whom was interested. However, Elder Lyman found an audience among some southern Saints who had settled on a tract developed by him near Holladay, a few miles southeast of Salt Lake City, and who still felt uncomfortable in Utah’s harsh climate.

Jefferson Hunt, following a year of gold mining in California, returned to Utah in early February 1851, via the southern route, carrying a letter from Isaac Williams to Charles C. Rich. Once again, Williams offered to sell the ranch: [5] “I make this proposition in consequence of ill health, and not being able to manage things, as the country is at present, as I could wish.”

In the “President’s office,” on Sunday evening, 23 February 1851, Amasa M. Lyman was “set apart to take a company with Elder Charles C. Rich to Southern California, to preside over the affairs of the Church in that land and to establish a strong hold for the gathering of the Saints.” [6] Brigham Young authorized Elders Lyman and Rich to recruit others to go to Southern California.

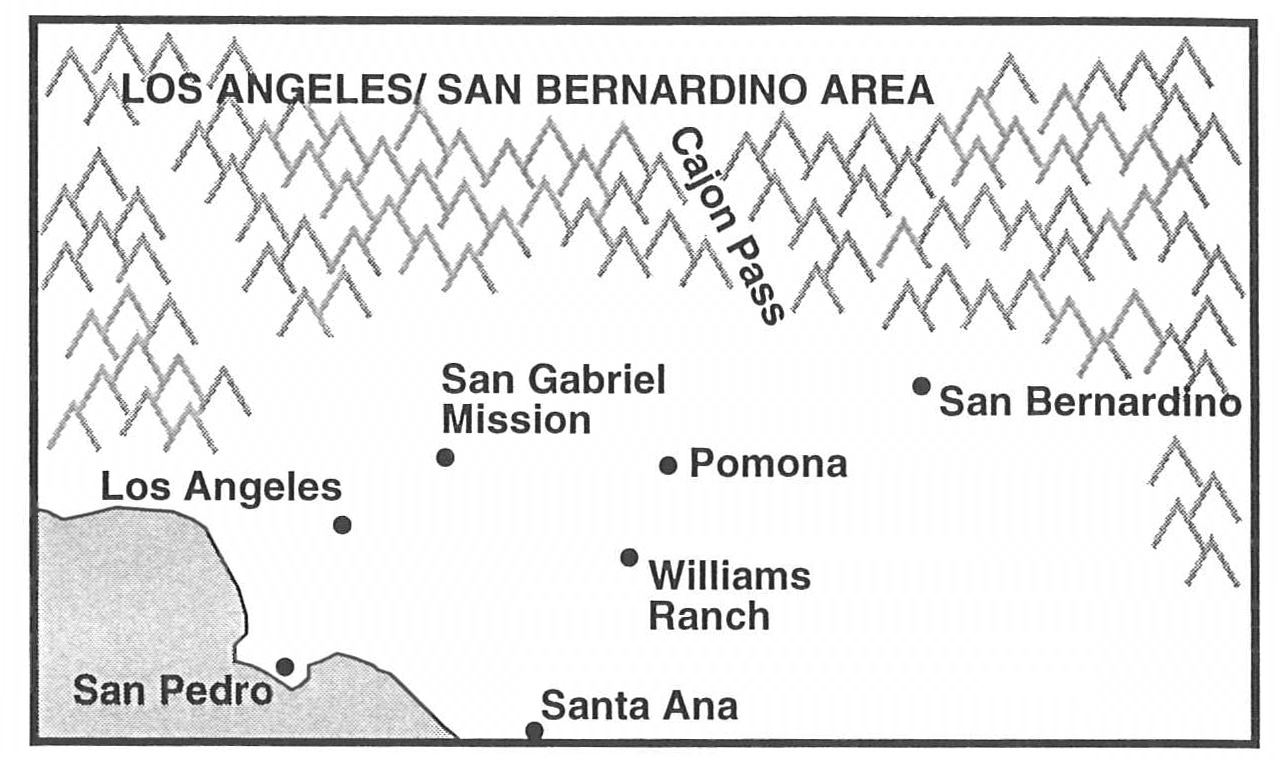

President Young directed the two apostles “to select a site for a city or station, as a nucleus for a settlement, near the Cajon pass, in the vicinity of the sea coast, for a continuation of the route already commenced from this to the Pacific [and] to gather around them the saints in California.” He also wanted them to plan a mail route to the coast and to cultivate such subtropical products as olives, “grapes, sugar cane, cotton and any other desirable fruits and products . . . [and] to plant the standard of salvation in every country and kingdom, city and village, on the Pacific and the world over, as fast as God should give the ability.” [7]

In March, 437 volunteers, among whom were natives of every state but two and natives of eight foreign countries, met with their 150 wagons at Peteetneet (present-day Payson, Utah, sixty miles south of Salt Lake City), anxious to go even though a sale of the Rancho had not been completed. When Brigham Young traveled south to send them off with his blessing, he “was sick at the sight of so many of the Saints running to California, chiefly after the god of this world.” [8] He was so upset at the spectacle that he was unable to address them as planned. This was “one of the few recorded instances when he was without words.” [9]

On 24 March the group left, accompanied by Elders Lyman, Rich, and Parley P. Pratt. Elder Pratt had been appointed mission president “of all the islands and coasts of the Pacific,” with headquarters in San Francisco. In addition to his role in selecting the corridor’s way station sites, Elder Pratt knew many of the Brooklyn Saints from their East Coast days and thus was also prepared to address the difficult matter of Sam Brannan.

The journey was grueling. The California-bound party encountered blizzards, mud, and Indian attacks in Utah, and thirst in the deserts of Nevada and California—at one point going fifty miles without water. [10] On 11 June the last wagon arrived at a previously designated sycamore grove on the edge of the San Bernardino Valley near Devore.

Securing a Place to Settle

Amasa Lyman and Charles Rich went ahead to negotiate with Williams. However, to their astonishment and dismay, he had changed his mind and now refused to sell at any price. One historian has wondered if the boom in the cattle business, due to the growing population in Northern California, had been “a recuperative influence on Williams’ health.” [11] The party remained camped all summer in the sycamore grove while a search went forward for another site.

The situation became increasingly grave. After extensive searching, the only available land they could buy was the Lugo brothers’ San Bernardino Rancho. Elders Lyman and Rich had hoped to purchase between eighty and one hundred thousand acres for approximately fifty thousand dollars and were therefore disheartened when the Lugos demanded $77,500 for their property—much more than the price Williams had quoted earlier. Nevertheless, on 29 June, they decided to purchase it.

Elders Lyman and Rich went to San Francisco to solicit enough money from the prosperous Northern California Saints to begin buying the Ranch and to feed their large group of stranded immigrants. For the next several days, with the help of Elder Parley P. Pratt (who was already in San Francisco), Elders Lyman and Rich, graphically depicting their need for help, visited the Saints, the gold missionaries in their camps, and even non-Latter-day Saints. Within two weeks they obtained eight thousand dollars worth of provisions and supplies and seven thousand dollars in cash, including two thousand dollars tithing from John Horner, all of which Elder Rich took back to Southern California on the brig Fremont. Elder Lyman remained in San Francisco to continue raising funds.

When Elder Rich reached San Pedro he was met by some forty teams, which the Latter-day Saint settlers had sent to carry the provisions back to their sycamore grove. Elder Rich, deciding to spend the night in Los Angeles, took the cash with him and checked into a hotel there. He did not spend the entire night, however, because “a mysterious something told him to rise and go on.” Consequently, he and his companions “took the carriage and started out.” At a certain point the road to San Bernardino forked. Rather than choosing the more popular “New Road,” Elder Rich decided to take the less-traveled “Old Road.” One of their mules became ill near Cucamonga, causing several hours’ delay. [12] As Elder Rich’s party approached the Saints’ settlement after midnight, they heard a gunshot behind them and hurried the remaining distance to the camp. [13] “We learned afterwards,” Elder Rich recorded in his diary, “that we were [to be] waylaid by a band of robbers, but passed them after they had given us up and laid down; in which I acknowledge the Lord’s protecting hand.” [14]

Finally, on 22 September 1851, the Ranch was purchased, with a down payment of seven thousand dollars, leaving a balance of over seventy thousand yet to be paid. The deed was in the names of Elders Lyman and Rich. The Saints immediately took possession of the Ranch, which included some adobe dwellings formerly occupied by Mexican laborers. Elder Lyman’s eleven-year-old son, Francis Marion, later recalled that his father’s five wives and their families were crowded “into a house with tile floors in two rooms. The other floors were of earth.” [15]

Developments in San Bernardino

While still camped in the sycamore grove on Sunday, 6 July 1851, the immigrants held a conference and organized the first stake in California. The apostles called David Seely to be stake president and William J. Crosby to be bishop of the fledgling community. Richard Hopkins, the new stake clerk, kept a meticulous journal which became the best single source for San Bernardino history. [16]

The colonists’ unity and resourcefulness were tested almost immediately. The threat of Indian warfare gripped all of Southern California in November 1851 as Chief Antonio Garra sought to lead a multi-tribe force in driving out all white settlers. Consequently, the Saints choseto follow what was by now a well-established pattern for their colonies. After the land was dedicated by prayer, a fort or stockade was erected which served as a temporary home and community center, as well as a protection against Indians. When the Saints’ night-and-day labors were done, the structure was the “most elaborate fortification ever attempted in southern California.” [17]

“When our people got the fort nearly inclosed,” Elder Rich’s wife, Emeline, recalled, “there came a terrible sand storm. It was the worst storm I have ever witnessed. The next morning we learned that this had been the night a certain band of marauders picked to drive us out. To this storm undoubtedly we owed our lives.” [18]

The fort was roughly rectangular in shape and measured 300 feet by 720 feet. “The north, south and east sides were made of cottonwoods and willow trunks with the edges fitted tightly together. The logs were sunk three feet into the ground, and they projected twelve feet above.... Loopholes were made, bastions built, and the gateways indented to allow crossfire.” Log houses along the west side formed the fourth wall, which was finished with timbers placed “in blockhouse fashion.” Additional log dwellings were constructed inside the fort. Some people slept in their wagons. Water from Lytle Creek, which ran through the enclosure, was stored in reservoirs. “A small group preferred to take their chances outside the fort, and camped on what later became the old cemetery.” [19] Although Garra was captured and executed a short time after the completion of the fort, the settlers continued to live within its walls for more than a year. [20]

Throughout this period of early development, a spirit of unity prevailed. Though the settlers were restricted to the fort “in a confined space that would test even the most neighborly,” there was “no evidence recorded of anything but continuous harmony.” [21] Elder Amasa Lyman reported to Brigham Young in September 1852 that “it is our feelings that the spirit of the Gospel is on the increase in this branch of the church, the best evidences of which are exhibited in the disposition of the people to observe and be governed by the council ordained for their edification. They still manifest a disposition to unite their efforts with ours to accomplish the payment for the place.” [22]

Amasa M. Lyman home

Amasa M. Lyman home

Church leaders in Utah shared Elder Lyman’s optimistic outlook. In a letter to Elders Lyman and Rich, the First Presidency announced: “We have written to Brother Pratt at San Francisco . . . to direct the Saints of the Society Islands to emigrate to your place, and put themselves under your care. . . . Their location . . . for their comfort and convenience will be in the same warm climate, in Southern California.” [23] President Young informed Elder Pratt that “we are pushing our settlements south as fast as possible, expecting that Brothers Lyman and Rich will meet us with their settlements this fall,” apparently indicating he expected the apostles to establish other settlements on the southern end of the Mormon Corridor. [24]

In December 1851, the colonists surveyed a “big field” of two thousand acres. They immediately went to work in a cooperative effort to plow the ground and plant their crops. [25] A year from the time they had purchased the land, the settlers were able to increase the yield as much as twentyfold, harvesting good crops of wheat, barley, and corn, and entering into active competition with the supply that had been coming from Chile and Peru.

Elder Parley P. Pratt, who passed through the colony in September 1852 on his way home from a brief mission to Chile, described a harvest feast in the bowery:

The Room was highly and tastfully ornimented, and set off with evergreens, specimens of Grains, vegitables etc. While above the Stand was written in Large Letters HOLINESS TO THE LORD The entire day and evening was spent in feasting dancing etc. Every variety almost which the earth produces, of Skill could prepare, was spread out in profusion, and partaken of by all citizens, Strangers, Spaniards or Indians, with that freedom and good order which is characterestic [of] the Saints. [26]

The Saints were also interested in furthering their intellectual pursuits. They had established a school while waiting in the sycamore grove. When a new Sunday School began meetings on 11 April 1852, Hopkins, the stake clerk, noted that it included “103 as happy-looking scholars as was ever seen, joined in praising the Heavenly Father for the blessings he continually bestows on us.” [27] During that same month a bowery was erected to serve as a chapel and day school for local children. [28]

Elders Lyman and Rich laid out the city in the grid pattern used at Salt Lake City. At its center they designated a “Temple Block,” although no temple was ever built there. [29] As the city began to take shape, more families constructed homes and engaged in public works. These projects required lumber, adobe, and other building materials. There was abundant timber in the nearby mountains, so the settlers decided to construct a sawmill there.

Mill at San Bernardino

Mill at San Bernardino

Building a road up the steep grade to the timber posed a great challenge. Every man in the settlement was called on to put in all his time and use all his teams and equipment in building the road and moving the machinery up to the sawmill. The resulting road was some twelve miles long and required over a thousand man-days of labor to complete. This was accomplished in just two and a half weeks during May 1852. The route was extremely steep, including grades of up to 41 percent. Unlike most lumber roads, which were private and charged tolls, the Latter-day Saint road was open for public use.

Jefferson Hunt, who had come with the initial colonizing group, was elected to represent them at the first board of supervisors meeting in Los Angeles County. He was also elected a member of the state legislature. Largely through his efforts, San Bernardino County was formed from Los Angeles and San Diego Counties in April 1853. [30] It was, and still is, the largest county in the contiguous forty-eight states.

The colony continued to grow and by 1856 had an estimated population of three thousand, making it the largest Latter-day Saint community outside Salt Lake City. [31] Unfortunately, the early optimism, unity, and success did not last.

Problems

As the colony prospered, various forces created challenges. The Church, in a special conference in Salt Lake City on 28 and 29 August 1852, made the first public announcement of its doctrine of plural marriage, or polygamy as it has been commonly called. Though outlawed in California, it was practiced, both overtly and covertly, by some of the Saints. This created controversy among the colonists themselves, as well as animosity among their neighbors.

Slavery was another controversial issue. Several Saints from Mississippi brought slaves with them. One of them became involved in Southern California’s “most important slavery case.” Robert Smith had brought two black mothers, Hannah and Biddy, and their twelve children and grandchildren with him to California, treating them in a manner somewhere “between freedom and paternalism.” When Smith decided to move with them to Texas (a slave state) where, he promised, their status would remain as it was, Mrs. Lizzy Rowen, who had formerly been owned by a Latter-day Saint, reported that Smith actually held them as slaves.

A trial was held and the judge, a Missouri transplant named Benjamin Hayes, ruled that Smith was viciously hypocritical, particularly in the case of four that had been born free in California. All fourteen slaves were declared free. [32]

As the economic boom fueled by the gold rush leveled off, agricultural surpluses were harder to sell, hampering efforts to make payments on the Ranch debt. [33] To further complicate matters, in 1853 the Saints learned that the property sold to them by the Lugo family contained only about thirty-five thousand acres—less than half of what the Saints believed they had acquired. This presented two substantial problems. First, because there was now less land to be partitioned and sold to individuals, Elders Lyman and Rich realized less cash toward the payment of their debt. Second, individuals interested in settling in the plush valley could purchase surrounding government property less expensively than they could purchase Ranch property. These lost revenues meant further financial difficulty. [34]

By 1853 these and other problems fueled internal strife, especially when Church leaders in Utah expressed concerns about Saints in California and when new arrivals gave only grudging deference to local ecclesiastical authorities. Even Amasa Lyman began lamenting the fact that the “foes against whom we have to contend are not shut out by adobe walls.” [35]

Early in the same year, Utah Church leaders asked about apostasy in San Bernardino. Elders Lyman and Rich reported that Henry G. Sherwood, a longstanding member and one of the original Utah Pioneers who had “held many positions of honor and trust in the Church,” had “totally failed to do what he promised us when on the way here which was to operate in connection with us in the accomplishment of our labors here.” [36]

Simmering dissent boiled over in 1855 during the county election. Although the two official Church candidates (chosen by Elders Lyman and Rich) won easily, their bids for election were contested by several other Latter-day Saints. One local resident, Battalion veteran Henry G. Boyle, observed that “these men came out in opposition to Amasa’s nominations, contrary to counsel,” and that they manifested a “regular mobb spirit.” He specifically noted that “this is the first opposition in elections we have had since we came into the country.” [37] Such open dissension rattled the faithful and encouraged the opposition. While the election itself did not cause the strife, it was “certainly a catalyst that brought the conflict into the open.” [38] The opposition candidates were quickly excommunicated for apostasy and immediately organized a “factionist” or “factionalist” or “Independent” party in San Bernardino dedicated to breaking the Mormon theocratic hold on the community.

The new party grew quickly. The “factionists” included several once-loyal Church members. Henry Sherwood joined, as did William Stout (the New Hope leader) and Addison Pratt’s long-time Polynesian missionary companion, Benjamin Grouard. Brooklyn passenger Quartus Sparks also joined and became “the most revengeful and acrimonious” of the former Latter-day Saints in San Bernardino. [39] In the fall of 1855, Richard Hopkins lamented: “The spirit of dissention is daily becoming more evident.” Amasa Lyman’s early prediction that problems in San Bernardino “would be started by those in our midst” was being fulfilled dramatically. [40]

The May 1856 elections touched off another round of controversy. The “Independent” party presented a full slate of candidates, and “notwithstanding the fact that only 26 anti- Mormon votes were polled at the municipal election, the spirit of disunion, [a] devastating sickness, was spreading over our once happy place,” wrote Hopkins. “It is almost impossible to insure the concert of action upon any object of the public interest. When will this end? The grand object appears to be the aggrandizement of private interests. To be a Latter-day Saint is becoming quite unpopular.” [41]

Property claims were a major source of friction in 1856. A government land commission had granted Elders Lyman and Rich the opportunity to select which thirty-five thousand acres they would settle. They delayed a final decision until 1856, when it became apparent that the “big field “ would not provide long-term productivity. The more arable lands they chose were along the river bottoms, where many outside the Church had settled during the interim. A conflict between the apostles (rightful owners of the newly designated lands) and the “squatters” heightened confrontations and ill feelings. A particularly hazardous encounter involved a disgruntled apostate named Jerome Benson. After ignoring a court order to abandon his farm, he and several others barricaded his cabin, complete with a cannon. Despite efforts to evict him, Benson remained until after the Saints left San Bernardino. At that time, he purchased a plot of government land some distance away, and his “fort” was razed.

The rift was further widened that year when the Independents decided to have “a regular old fashioned ‘back east’ Fourth of July celebration.” The Church party, however, went ahead with its own plans, and a somewhat humorous rivalry developed between the two groups. “The Independents procured a sixty-foot flagpole. The Mormons searched the mountains until they found one a hundred feet tall.” The Church group fired its salutes with a “little brass cannon/’ which their rivals condescendingly termed the “pop gun.” The Independents, on the other hand, brought a large cannon from Los Angeles “which made the mountains echo with its deep reports.” [42]

Elders Lyman and Rich took various measures to strengthen the Saints. As part of a larger Church movement, the two apostles advocated a “Reformation” beginning in late 1856. They appointed new “missionaries” to the Saints themselves. These new teachers sought to remind them of their duties and encouraged them to increase their faith and obedience. In December the apostles instituted a program of rebaptism, whereby the faithful could recommit themselves. Some five hundred individuals were rebaptized in two months. [43]

To pay off the Ranch debt and solve other financial problems, Elders Lyman and Rich formed a partnership with a wealthy Latter-day Saint, Ebenezer Hanks. A faithful member, Brother Hanks saw this partnership as not only a business venture with the possibility of profit, but also as a duty to the Church. He continued selling property and working toward payment of the debt even after the apostles left in 1857. [44]

In January of that year, Elders Lyman and Rich learned that they would leave later that spring for missions in Europe. [45] At the April conference in San Bernardino, they shared good counsel with the Saints as they bade farewell. In his remarks, Elder Lyman alluded to the possibility that the colony itself, now a hybrid of Saints and apostates, might be closed:

Suppose you are driven from this land; does this force you to apostacy and to forget God? It does not. What did you come here for? You came to build up the Kingdom of God . . . but you came to build up the Kingdom of God by improving yourselves. . . . If toil and perplexity is a reason for us to forget God, we have had plenty of that; but we have not forgotten God nor our duty, and what is true of us should be true of you. [46]

By 18 April 1857 the apostles had settled their affairs and were ready to leave. Feelings ran so high that they needed an “escort of 28 men and the sheriff to see them safely beyond reach of their blustering enemies.” [47] Neither ever returned.

The difficulties continued after their departure. On 20 June, a leader of the Independents was accused of killing a Latter-day Saint during a drunken brawl. The accused was arrested and the community became further divided as rumors circulated that the dissidents would break him out of jail. Eventually he was released when a grand jury failed to return an indictment against him. [48]

Speaking in Salt Lake City that same month, President Young was well aware of the mounting difficulties:

We are in the happiest situation of any people in the world. We inhabit the very land in which we can live in peace; and there is no other place on this earth that the Saints can now live in without being molested. Suppose, for instance, you should go to California. Brothers Amasa Lyman and Charles C. Rich went and made a settlement in South California, and many of the brethren were anxious that the whole Church should go there. If we had gone there, this would have been about the last year in which any of the Saints could stay there. They would have been driven from their homes. It is about the last year that brother Amasa can stay there. Were he to tell you the true situation of that place, he would tell you that hell reigns there, and that it is just as much as any “Mormon” can do to live there, and that it is about time for him and every true Saint to leave that land. [49]

As precarious as the situation was in San Bernardino, it would become even worse. Both internal and external events in 1857 would result in the abandonment of the colony, as will be seen in chapter 12. Nevertheless, the San Bernardino Saints left a lasting legacy in roads and structures, in education, and in farming technology. Without doubt the agricultural wealth accrued from Latter-day Saint farmers, who pioneered irrigation and other farming technologies that made agriculture viable in an otherwise uncultivated region, is a far greater heritage than the wealth contributed by digging gold. As Brigham Young surmised, it was agriculture that in the long run proved to be the backbone of California’s wealth. And though the San Bernardino colony was short-lived, it made a lasting contribution.

Notes

[1] Journal History, 14 May 1847 (hereafter JH); LDS Church Archives.

[2] Ibid., 30 September 1849.

[3] Millennial Star, 12, no. 14 (15 July 1850): 214–15.

[4] Donna T. Smart, “Over the Rim to Red Rock Country: The Parley P. Pratt Exploring Company of 1849,” Utah Historical Quarterly 62, no. 2 (spring 1994): 171–90.

[5] Isaac Williams to Charles C. Rich, December 1850, quoted in George William Beattie and Helen Pruitt Beattie, Heritage of the Valley: San Bernardino’s First Century (Pasadena, Calif.: San Pasqual Press, 1939), 177.

[6] JH, 23 February 1851.

[7] “History of Brigham Young,” 23 March 1851, quoted in Joseph S. Wood, “The Mormon Settlement in San Bernardino: 1851–1857” (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1968), 69–70.

[8] Quoted in Wood, 71; see also Leonard J. Arrington, Charles C. Rich: Mormon General and Western Frontiersman (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 159.

[9] J. Kenneth Davies, Mormon Gold: The Story of California’s Mormon Argonauts (Salt Lake City: Olympus, 1984), 306.

[10] “A Mormon Mission to California in 1851 from the Diary of Parley Parker Pratt,” ed. Reva Holdaway Stanley and Charles L. Camp, California Historical Quarterly 14, no. 1 (March 1935): 59–69; Autobiography of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 371–81.

[11] Wood, 83.

[12] A. Harvey Collins, “At the End of the Trail,” Annual Publications Historical Society of Southern California 9 (1919): 71–72.

[13] John Henry Evans, Charles Coulson Rich: Pioneer Builder of the West (New York: Macmillan, 1936), 208.

[14] Quoted in Beattie and Beattie, 181–82.

[15] Albert R. Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman: Trailblazer and Pioneer from the Atlantic to the Pacific (Delta, Utah: Melvin A. Lyman, 1957), 208.

[16] Wood, 85; Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 193.

[17] Ibid., 103.

[18] Charles C. Rich Family Association, Biography of Emeline Grover Rich (Logan, Utah: 1954).

[19] Annaleone D. Patton, California Mormons by Sail and Trail (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1961), 139–40.

[20] Beattie and Beattie, 184–87.

[21] Edward Leo Lyman, “The Rise and Decline of Mormon San Bernardino,” BYU Studies 29, no. 4 (fall 1989): 46.

[22] Quoted in ibid., 61 n. 9.

[23] Quoted in Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:81.

[24] Quoted in Albert R. Lyman, 208.

[25] Millennial Star 14, no. 31 (25 September 1852): 491.

[26] 4 September 1852: “A Mormon Mission to California in 1851,” 180.

[27] Quoted in Campbell, 201.

[28] Millennial Star 14, no. 31 (25 September 1852): 491.

[29] Ibid.; Campbell, 201–2.

[30] Pauline Udall Smith, Captain Jefferson Hunt of the Mormon Battalion (Salt Lake City: The Nicholas G. Morgan, Sr., Foundation, 1958), 172; see also Beattie and Beattie, 135.

[31] Campbell, “Brigham Young’s Outer Cordon: A Reappraisal,” Utah Historical Quarterly 41, no. 3 (summer 1973): 242–43.

[32] Rudolph M. Lapp, Blacks in Cold Rush California (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1977), 120–21; Beattie and Beattie, 186 n. 13.

[33] Edward Leo Lyman, 47.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Quoted in ibid., 48–49.

[36] Campbell, “A History,” 208; quoted in Edward Leo Lyman, 50.

[37] Henry G. Boyle Diary, 21 April 1855; typescript, Brigham Young University Archives.

[38] Edward Leo Lyman, 52.

[39] Campbell, “A History,” 209–11; Wood, 215–16.

[40] Edward Leo Lyman, 53.

[41] Richard Hopkins Diary, quoted in Campbell, “A History,” 211.

[42] Wood, 220–21.

[43] Campbell, “A History,” 212–13.

[44] Edward Leo Lyman, 57–58.

[45] Arrington, 204–5.

[46] Hopkins, quoted in Campbell, “A History,” 214.

[47] Albert R. Lyman, 222.

[48] Wood, 232–34.

[49] Journal of Discourses (Liverpool: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1857), 4:344.