Roots and Branches: 1900–19

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 247–62.

The opening years of the twentieth century are known in United States history as the “Progressive Era.” It was a time when the collective American mind was stretched. This expansive mood was also reflected in the Church. On New Year’s Day 1901, the Church president, eighty-six-year-old Lorenzo Snow declared: “I hope and look for grand events to occur in the twentieth century. At its auspicious dawn I lift my hands and invoke the blessings of heaven upon the inhabitants of the earth. . . . Let all people know that our wish and our mission are for the blessing and salvation of the entire human race. May the twentieth century prove the happiest as it will be grandest of all the ages of time.” [1]

This optimistic statement, with its broad vision, assured Latter-day Saints that gospel blessings were for all, regardless of where they lived. This, together with President Snow’s emphasis on tithing, which brought the Church financial stability, gave impetus to growth in many areas, including California. Following President Snow’s death later in 1901, his successor, President Joseph F. Smith, continued this same emphasis.

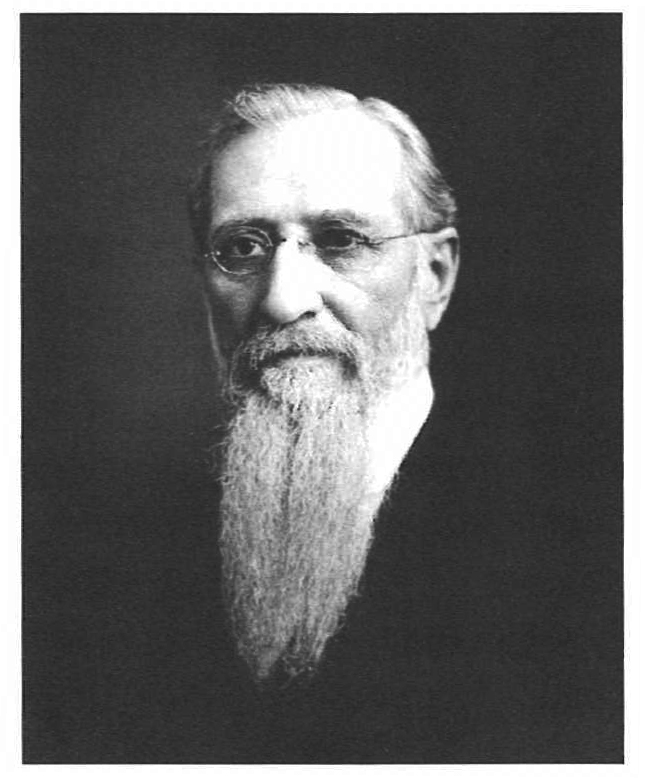

By the time Joseph F. Smith became Church president, he had served as counselor to Presidents Brigham Young, John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow. A man of seemingly boundless goodwill, President Smith’s cheerful optimism earlier in California while staring down the barrel of a gun was a prelude to his entire administration. Somehow he always remained open and tolerant despite blistering personal attacks from the press and others.

Joseph F. Smith

Joseph F. Smith

Following the lead of his predecessors, President Smith encouraged Church growth outside the Intermountain West, where with his nurturing the Church began to take root, branch out, and permanently flourish in a way it had not done for half a century. President Smith was already familiar with California; in addition to passing through the state to and from his boyhood mission to Hawaii, he was in California again during the 1860s and 1880s en route to the Islands. He also spent time with the Saints in San Francisco in 1896.

The California rebuilding process began in earnest when a proven leader and seasoned public servant, Joseph E. Robinson, was appointed mission president. President Robinson’s eighteen-year administration, which both in time and vision mirrored that of President Smith, laid a permanent foundation for future Latter-day Saint development in California.

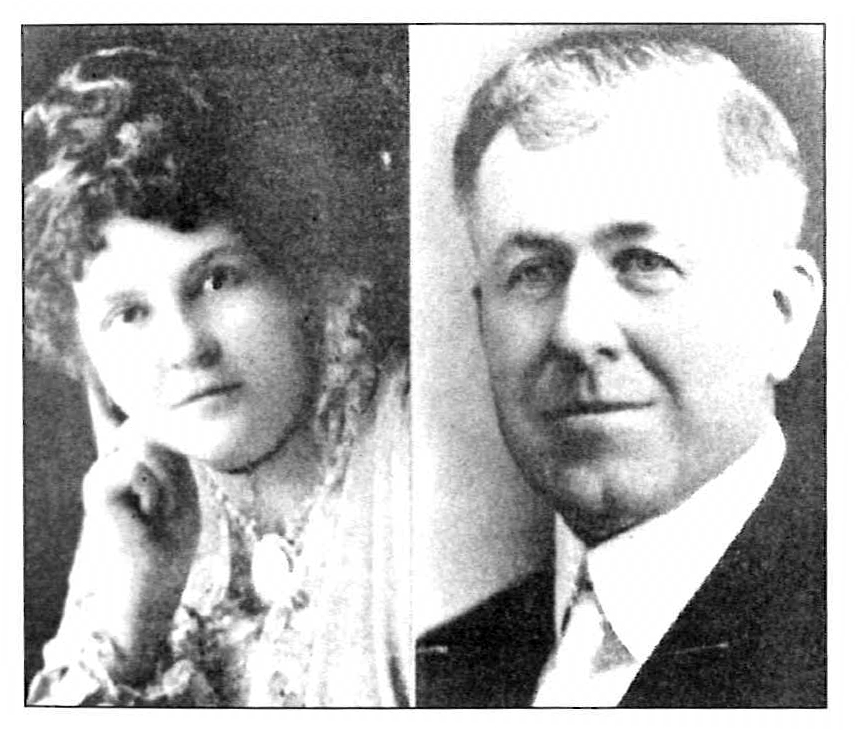

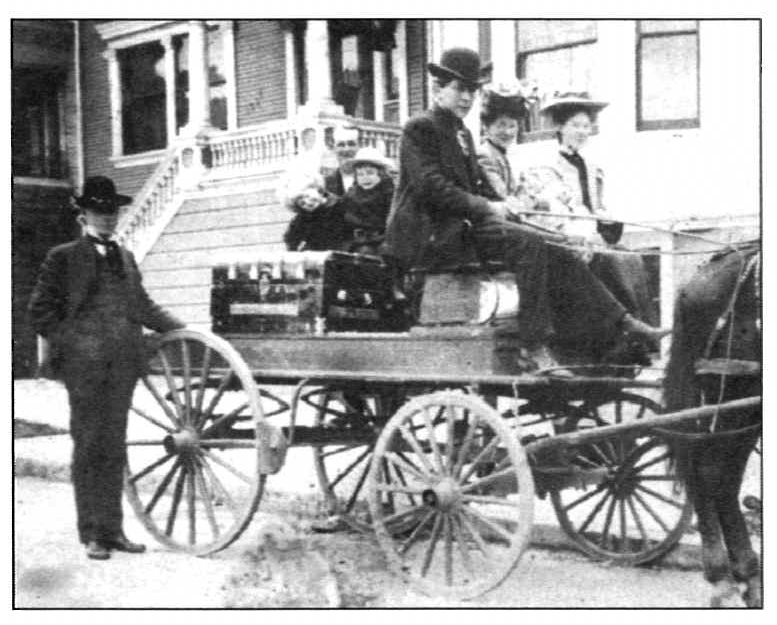

Mission president Joseph E. Robinson and his wife Minnie

Mission president Joseph E. Robinson and his wife Minnie

Born in the small Southern Utah town of Pinto to English-immigrant parents, Robinson was raised in nearby Kanab. When he left his family behind to go to California in June 1900, his assignment was that of an ordinary missionary. However, he was not the typical young elder with minimal experience, and by the end of the year he was called to be mission president. His wife and family then came to join him.

He had served as Kane County (Utah) assessor and clerk, chairman of the Republican Party, and representative in the Utah State Legislature. As a legislator, he helped write Utah’s constitution and chaired the committee which purchased the site upon which the state capitol now stands in Salt Lake City. Like his prophet leader, President Robinson was a well-proportioned man of regal bearing, standing approximately six feet tall. His face was ruggedly handsome, displaying a perpetual smile. His personality reflected wisdom and compassion.

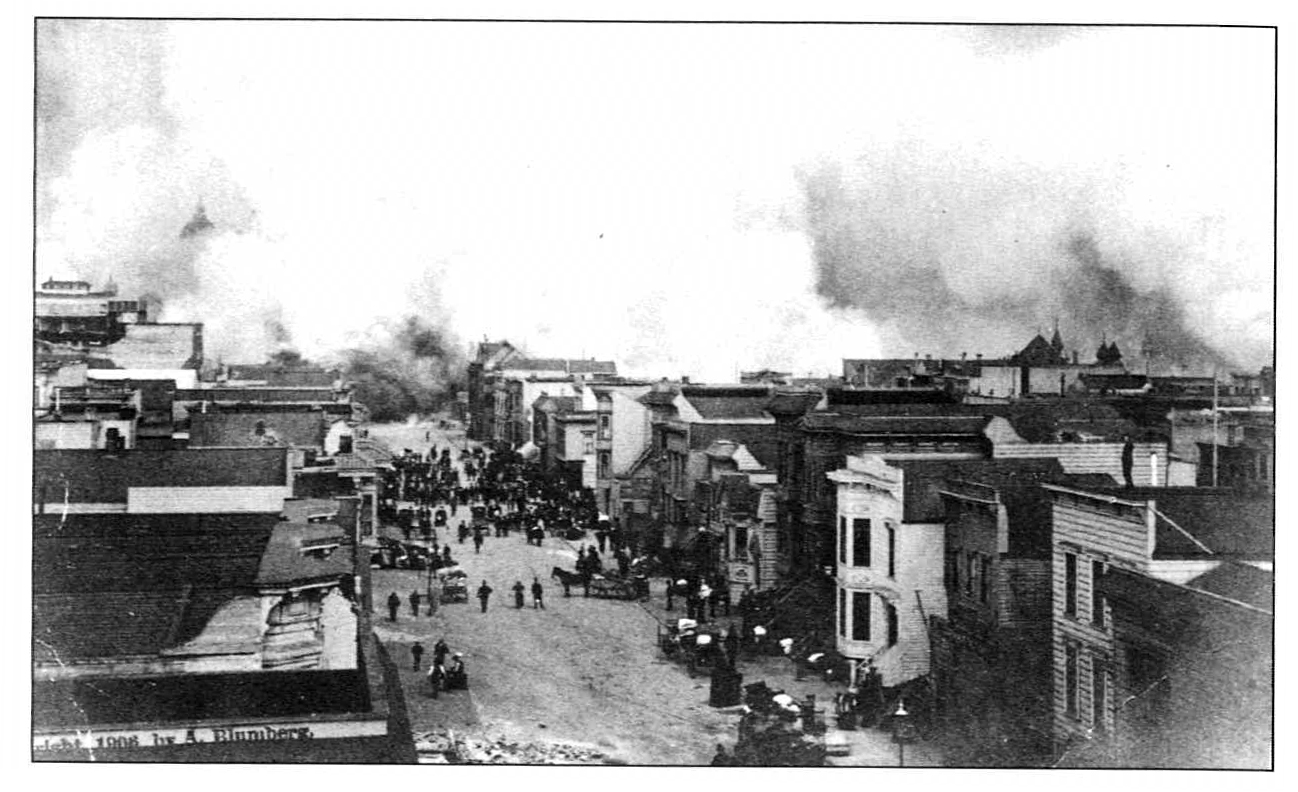

The San Francisco Earthquake

The biggest event of the early 1900s in San Francisco was an act of nature. One-third of the way into President Robinson’s service, on 18 April 1906 at 5:12 A.M., a cataclysmic event occurred that changed the course of Church history in California. It was the great 1906 earthquake and subsequent fire that destroyed 490 blocks and dealt a nearly mortal blow to the city.

The night before, a missionwide conference had concluded with a Mutual Improvement Association gathering at the mission home at 609 Franklin Street. In addition to the missionaries and local members, five elders en route to the South Seas and former apostle Matthias Cowley were also present. When one of the missionaries was called on to offer a closing prayer, he prayed that something might happen to “wake up San Francisco and make it receptive to the gospel.” After the events of the following morning, the Robinsons sought to console the elder, who feared that his prayer had caused the disaster. [2]

San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906

San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906

Cowley and the five elders bound for the Pacific believed that they had received divine protection: their rooms were the only portions of their hotels which had not been damaged. When the five went to check on their luggage at the railway station, they were told that it had been transferred to a building across the street, which, by this time, had burned to the ground. Three days later, one of the missionaries was impressed to go back and check again. He was grateful to discover that all of their possessions were still in the station baggage room, and none had been destroyed or stolen. [3]

Local member Harold R. Jensen described some of the quake’s effects:

My family was burned out on the first morning of the fire, and we brought what few belongings we had saved to the Hooper family home on Golden Gate Avenue, a half block from the mission house. We seemed safe there but later in the day another fire had started in the neighborhood and on our second trip to the house, we found the Hooper family with their belongings in a truck, ready to flee. Together with some of the missionaries, all of us drove away and camped that night in a barn on a ranch near Colma. The missionary house was later burned, one of the last blocks to be destroyed by fire. [4]

George C. Carpenter, special correspondent for the Deseret News, described the area between City Hall and mission headquarters (609 Franklin) as “ash heaps.” “All that remained of ‘609’ was part of an iron fence, a bathtub, and a half-burned telephone pole ‘to which was tacked the cards of several elders and notice to latter-day Saints to gather at Jefferson Park.’” [5] President Robinson, the missionaries, and several local Latter-day Saint families set up camp in this park three blocks away. Even though there was widespread panic among the general population, President Robinson observed a rather different reaction among the faithful Saints, whose mood was similar to that of the Brooklyn passengers in their hour of peril sixty years before: “There was no hysteria, abandonment to grief, despair or complaint manifest. All seemed to possess that ‘peace of mind that surpasseth understanding’ which comes only to those whose ‘hopes were secure in the promises of the Father.’” [6]

The quake had a lasting impact on Church activity in San Francisco. In the midst of such crises, people often turn from material concerns to more enduring spiritual values. Two months after the disaster, President Robinson reported that “the Saints are more attentive to their duties since the dread calamity.” [7]

In aftermath of 1906 earthquake and fire, LDS Broberg family

In aftermath of 1906 earthquake and fire, LDS Broberg family

loads their possessions to leave San Francisco

With the destruction of the mission home in San Francisco, President Robinson concluded that the time was right to move his headquarters to Los Angeles, where Church membership was larger and where a direct rail link with Salt Lake City had been completed the previous year. Headquarters were first established there at 516 Temple Street. Later the offices were moved to 423 West Tenth Street, where they remained for a number of years until a permanent building was constructed.

After moving his family to Southern California, President Robinson immediately returned to San Francisco, where he was involved “for some time helping the Saints readjust” and in distributing relief funds and supplies which poured in from Latter-day Saints in many areas. Relief Society women in Hawaii, for example, sent fifty dollars to help their suffering sisters. [8]

One of those devastated by the quake was Joseph F. Smith’s cousin, the poet Ina Coolbrith. The quake destroyed her unpublished manuscripts and irreplaceable mementos; it also destroyed her home and left her destitute. Letters of condolence and gifts came from all over the world. Her California friends and fellow writers initiated projects to help her, one of which was a book of short stories, poems, and articles. This and other undertakings proved successful. A substantial amount of money was accumulated, and a home was bought for the much-loved poet.

Modern-Day Pioneers

Consistent with the Church’s progressive attitude, leaders continued to send clear signals that settlement in California would not only be condoned but encouraged. Consequently, during the opening decades of the twentieth century, many Latter-day Saint “pioneers” came to the Golden State. In the autumn of 1906, the California Irrigated Land Company, a farming co-op interested in utilizing water from the Feather River to bring additional acres into production, sent a representative to the Intermountain West to recruit Latter-day Saint farmers to the small Northern California town of Gridley. Those solicitations fell upon the receptive ears of some Latter-day Saints in and around Rexburg, Idaho, who agreed to settle in California despite the devastating earthquake earlier in the year.

The first party, headed by George Cole and family, arrived in California on 22 November. They boarded for a week at the Gridley Hotel at the expense of the land company. Locating approximately two miles south of town, the group increased to more than fifty by the end of the year.

On 23 February 1907, under the direction of President Robinson, the Gridley Branch was organized with the following officers: George Cole, president, and J. F. Dewsnup and Charles Larsen, counselors. Since those early meetings, Latter-day Saint activities in Gridley have been continuous. [9]

Other pioneers came individually or as families. Many were rugged, talented, and sufficiently self-assured to expose their faith to a California environment of tiny, struggling branches amid a sea of disinterested, sometimes disapproving non-Latter-day Saints. The twentieth-century influx of Saints into California was in marked contrast to that of the nineteenth century. Most now came on their own rather than through Church sponsorship. “It is quite probable, however, that many would not have come to California in opposition to Church policy,” one historian has concluded. “The facts seem to be that the Church leaders had ceased to oppose the movement of members away from the centers of the Church and had come to regard this movement as a possible means of strengthening the Church in the mission fields. This was especially true of the California Mission.” [10]

Some Latter-day Saints participated in the early development of the motion picture industry. Waldamer Young of Salt Lake City worked for the San Francisco Chronicle for about a decade before moving to Hollywood in 1912; he wrote the screen scenarios for Lives of a Bengal Lancer and The Plainsman, which featured Mary Pickford, the famed silent movie star. [11] Other noted Latter-day Saint screenwriters during this period were Harvey H. Gates and Eugene B. Lewis.

The Saints engaged in business, political, social, and cultural activities. Martella Lane, an Iowa native who came to California in 1900, became known as the “Artist of the Redwoods,” painting numerous landscapes of these beautiful trees. She also created murals of the Sacred Grove in at least two Southern California chapels. Daniel Lillywhite headed the Los Angeles Livestock Exchange for twenty-five years, and Nephi E. Miller pioneered large-scale honey production. James H. Cannon, an electrical contractor, presided over the Los Angeles Rotary Club; Horace T. Perry became a Bank of America executive; and W. Ed Wallace became president of the California Association of Realtors. Ettie Lee, a native of New Mexico who came to Los Angeles in 1914, became a prominent Los Angeles public school educator and philanthropist. She taught immigrant mothers and girls how to clothe themselves attractively and how to make their lives more comfortable by producing homemade quilts and rugs. She eventually founded the widely acclaimed Ettie Lee Homes for Boys. T. Earl Pardoe founded the first speech clinic at the University of Southern California, and John W. Freestone helped establish the Los Angeles College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons. Businessman Jesse Knight came to develop mines in the Mojave desert, and his son, Goodwin, later became a California governor.

Hyrum G. Smith, a great-grandson of Joseph Smith’s brother, Hyrum, came to Los Angeles to study dentistry at the University of Southern California. On 29 May 1910 he was appointed president of the Los Angeles Branch, the third man to serve in that capacity. Having been awarded a gold medal for proficiency in his studies, he established a local practice upon his graduation in 1911. However, he had just begun when he was called from California on 9 May 1912 to serve as Patriarch to the Church. [12] He left for Salt Lake City as the first person called as a General Authority while living in California. At that time, the Patriarch to the Church was selected among descendants of Hyrum Smith and had the responsibility of giving blessings to Church members not residing in organized stakes. The position no longer exists in the Church.

Once again the Church began calling missionaries from California to serve in various parts of the world. Perhaps the first in the twentieth century was Eliza Woollacott’s grandson, Albert Henry Thomas, who left from Los Angeles on 18 June 1903 for Britain.

Early Church Buildings

In 1908 President Joseph F. Smith came to California to tour the mission, underscoring the state’s growing importance. He was the first General Authority to extensively visit Church units in the state since the 1850s; he was also the first president of the Church ever to do so.

By this time, some Church branches were becoming well organized and thinking about building permanent meeting houses. The first Church building of the modern era in California was constructed in Gridley during the winter following President Smith’s mission tour. The Saints called their building, which was two and one-half miles southwest of Gridley, Liberty Social Hall. Though it was not intended to be a permanent worship facility, the first religious meeting was held in this hall on Sunday, 4 July 1909.

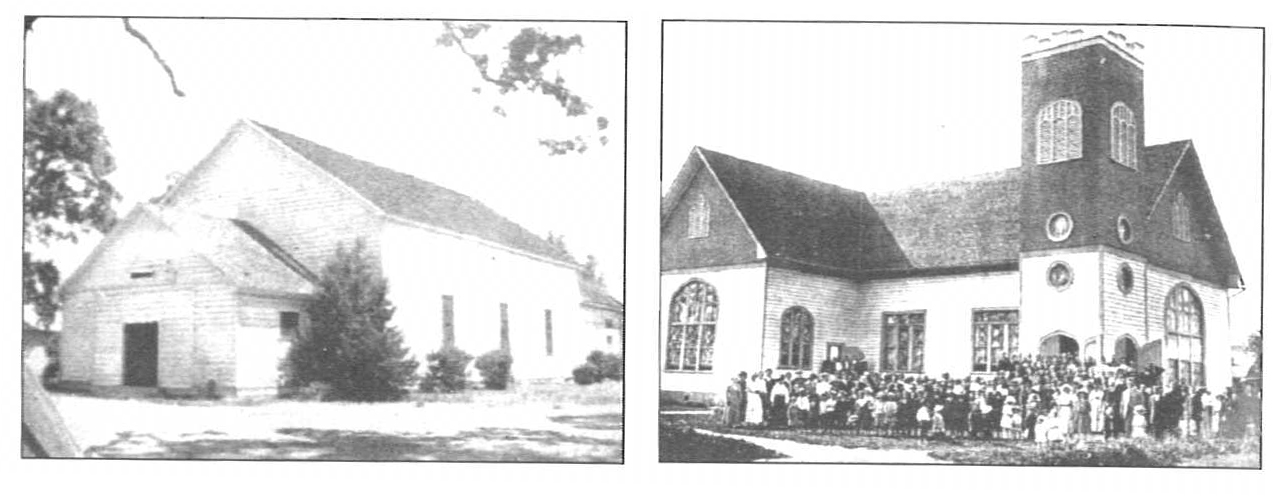

1909 Social Hall (left) and 1912 chapel (right) at Gridley

1909 Social Hall (left) and 1912 chapel (right) at Gridley

In 1912 a more suitable chapel was built at a cost of twelve thousand dollars. This meetinghouse was the “largest house of worship belonging to the Latter-day Saints west of Salt Lake City” and the first Church-owned chapel in California. [13] The LDS group in Gridley was at that time the Church’s largest branch in the Far West.

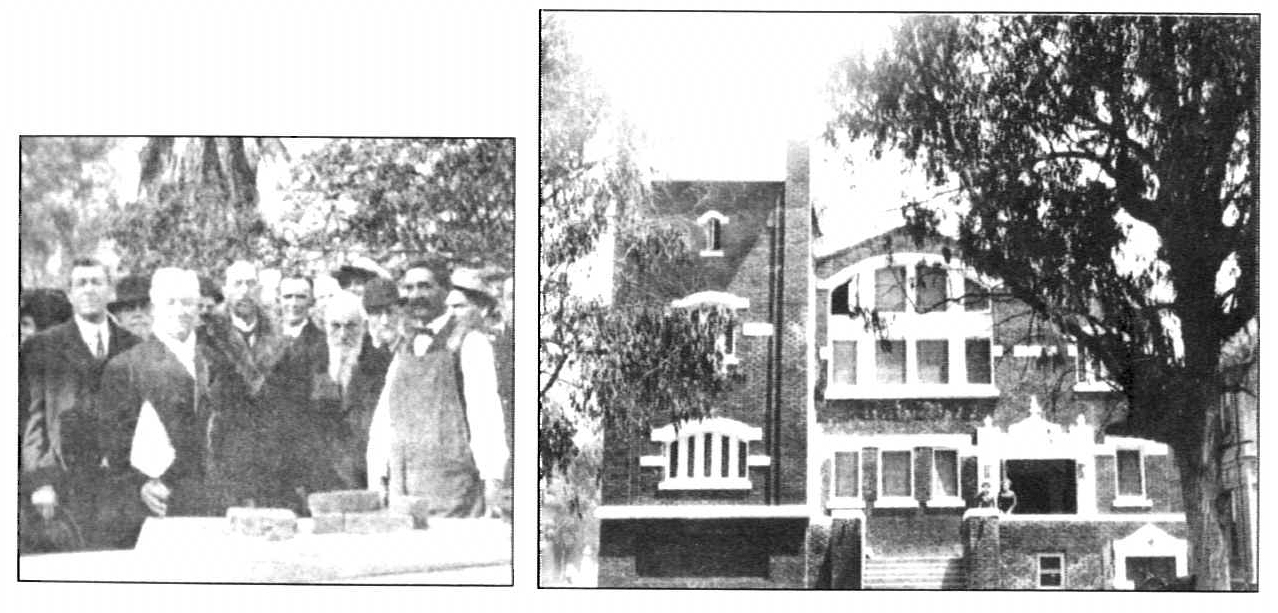

To underscore the importance to Church leaders of a successful Latter-day Saint presence in Southern California, the first chapel in Los Angeles drew Anthon H. Lund of the First Presidency and George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve to lay the cornerstone. Upon its completion, the building was dedicated by President Joseph F. Smith on 4 May 1913. The chapel was located at 153 West Adams Boulevard, adjacent to the mission headquarters building, which was completed at that same time. This “Adams Chapel/’ as it came to be called, together with the Los Angeles Branch, which met there, was a focal point of Church growth and activity in Southern California for many years. It became a place where friendships for the entire Latter-day Saint community were begun and renewed.

Anthon H. Lund (with trowel), Joseph E. Robinson (to his right), George Albert Smith (to President Lund's left), and others at 1913 cornerstone laying for Adams chapel (right)

Anthon H. Lund (with trowel), Joseph E. Robinson (to his right), George Albert Smith (to President Lund's left), and others at 1913 cornerstone laying for Adams chapel (right)

President Smith developed such a fondness for California that he acquired a winter home in Santa Monica that same year. There he became even more intimately acquainted with President Robinson and the local California Saints.

Next, the San Diego Branch, under the leadership of its president, Stephen Barnson, purchased a chapel site at Tenth and Pennsylvania Streets. After two years of planning and raising money, a chapel was completed and dedicated on this site in the spring of 1916.

1915 World Fairs

In 1915 California celebrated the completion of the Panama Canal by sponsoring two world fairs, the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, and the Panama- California Exposition in San Diego. Even though the Church did not formally participate at either fair, several Latter-day Saints were involved because the state of Utah had its own building at both.

Several specialized “congresses” were organized in conjunction with the San Francisco Fair. Latter-day Saints were especially involved with the International Congress of Genealogy, with Church members being invited to organize and conduct several of the sessions. A special train called the Utah Genealogical Special was chartered to bring 250 persons from Utah, including the First Presidency. All three members of the First Presidency spoke at sessions of the genealogy congress.

“Utah Day” at the San Francisco Fair was observed on 24 July. In his remarks, President Joseph F. Smith recalled his memories of the Bay Area sixty years earlier, when “only a few houses were at San Francisco.” The Church leaders “were cordially received and treated with great respect. Many prominent men and women called on them and sought interviews.” [14]

Another significant Latter-day Saint representative was James E. Talmage of the Quorum of the Twelve, who addressed the Congress of Religious Philosophy. His outstanding lecture, “The Philosophical Basis of Mormonism,” became a classic of Latter-day Saint thought and was reprinted in pamphlet form for many years.

Another fair participant was young Avard Fairbanks, a Utah artist and sculptor, who made his first visit to California to exhibit his work. Joseph Ballantyne also brought his Ogden Tabernacle Choir to perform at both the San Francisco and San Diego fairs.

Ina Coolbrith, still in good health though in her seventies, undertook the task of organizing the International Congress of Authors and Journalists. She contacted nations and groups worldwide, personally writing letters by hand over a period of four years. At the conclusion of the congress on 30 June 1915, President Benjamin Ide Wheeler of the University of California crowned her with a wreath of California laurel. The state legislature passed a resolution declaring her the first poet laureate of the state of California. She was so highly regarded that on the day of her funeral in March 1928, the state legislature declared a day of mourning and named a 7,900-foot mountain in her honor. Mount Ina Coolbrith commands the north side of Beckworth Pass, through which this young niece of Joseph Smith had entered California three-fourths of a century earlier. San Francisco still honors her. A hillside park bearing her name overlooks the site of the former Latter-day Saint village and the beach at its feet.

The End of an Era

On 6 April 1917 the United States entered the First World War, which had broken out in Europe three years earlier. The Church, though it supported the position of the U.S., encouraged all members to support their own countries, even through military service.

Before the war, relatively few Latter-day Saints had moved to or made extensive visits to California. Now whole groups of LDS servicemen were trained in or passed through California, taking firsthand looks at the state. Utah’s volunteer unit, the 145th Field Artillery (1st Utah), received its basic training at Camp Kearny, just north of San Diego, during the fall of 1917. Many of these servicemen later returned and made permanent homes in California.

The year 1918 marked a major milestone in the course of both world and Church events. To the world, it brought peace. To the Church, it brought the end of an era: within two weeks of the armistice, President Joseph F. Smith died. Soon after, President Robinson, who had labored diligently for nearly two decades, received his honorable release, thus ending the long and parallel Church service of the visionary prophet and the faithful California mission president. From a few hundred Church members in 1900, most of whom were migrants from Utah, membership grew to over three thousand during President Robinson’s tenure. The number of branches climbed from five to nineteen. Although there were no temples or other ornate structures, the value of Church property increased from almost nothing to over one hundred thousand dollars. [15]

As a testimonial of their deep affection for President Robinson and his wife, the members of the Church in Southern California gave them a building lot on Buckingham Road in Los Angeles, together with four thousand dollars to build a home. The presentation was made on 21 April 1919, at a reception hosted by officers and members of the Los Angeles Conference. Robinson entered the real estate business and continued to be a much-loved and respected Church leader. His Sunday School class in the Wilshire Ward attracted large crowds. Following his death in August 1941, his family interred his remains in his adopted state. His former missionaries erected a fitting monument to his memory at the Inglewood Cemetery.

During the first two decades of the twentieth century, faithful California Saints proved to Church leaders and members that devotion and faithfulness could be maintained and strengthened in a modern urban setting. These Latter-day Saint immigrants stayed close to their Church—a prodigious feat given the scattered condition of Church members and the comparatively primitive communication, transportation, and meeting facilities. The Church in California was now ready for its next plateau: the first stake outside of predominantly LDS communities.

Notes

[1] Deseret News, 1 January 1901.

[2] William G. Hartley, “Saints and the San Francisco Earthquake,” BYU Studies 23, no. 4 (fall 1983): 432.

[3] Ibid., 437, 451–52.

[4] Harold R. Jensen, interviewed by J. Edward Johnson, 15 May 1935, Oakland Stake Collection.

[5] Hartley, 454.

[6] Ibid., 458.

[7] Quoted in ibid., 457.

[8] Ibid., 454–55.

[9] Gridley Reunion Committee, History of the LDS Church in the Gridley, California Area (Gridley, Calif.: McDowell Printing, 1980), 1–2.

[10] Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 348–49.

[11] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:493.

[12] Lawrence R. Flake, Mighty Men of Zion (Salt Lake City: Karl D. Butler, 1974), 311–12.

[13] History of the LDS Church in the Gridley, California Area, 3.

[14] Gerald Joseph Peterson, “History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1974), 38–39.

[15] Andrew Jenson, comp., “The California Mission,” 19 April 1919; LDS Church Archives.