New Beginnings: 1887–1900

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 229–46.

In its early years, California had its ups and downs. There were exciting gold discoveries and wild speculations in land, mining, and railroad stocks. But interspersed among these were periods of economic depression. By the 1880s, California had become stable and sober, providing a setting more conducive to the replanting of Latter-day Saint roots.

The Saints had likewise been through their own years of sobering and leavening. Continuous challenges—repeated persecutions, forced uprootings from their homes, an epic overland migration, a hard desert, and the onslaught of a hostile United States army—had crystallized within them a solid confidence in themselves and in their faith. This, together with improved communications and transportation, prepared them to reach out and write a new chapter in their California history.

Seeking Help in California

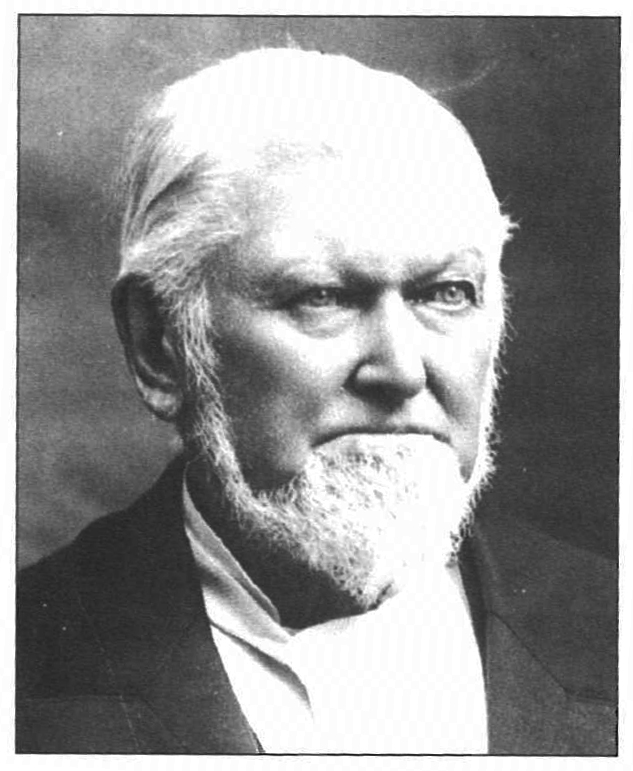

The new chapter began when Wilford Woodruff succeeded John Taylor as president of the Church. The changes he would institute were so dramatic that they now rank among the most important in Latter-day Saint history. His life’s experiences helped prepare him to provide leadership for the new opportunities which were opened to the Church during the 1890s. Interestingly, both of his counselors, George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith, had spent time in California.

Wilford Woodruff

Wilford Woodruff

When President Woodruff took over, the Church’s very survival was hanging in the balance. Not only had it been disenfranchised by the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act, but some members of the U.S. Congress were now urging even more drastic measures which would effectively deprive every Latter-day Saint of the right to vote. The situation was discouraging.

President Woodruff was convinced that he needed to take action. An aggressive pursuit of Utah statehood might be the answer. Where could he turn? Utah representatives in Washington could not help, because they had little influence there.

Some of President Woodruff’s early missionary success was in Saco, Maine, where the Brannans and Badlams had lived. It was after he had served there that the Badlams took young Samuel Brannan with them to settle near Kirtland, Ohio. The Badlams’ son, Alexander Jr., was now politically well connected and respected in San Francisco. So in September 1887, just a few weeks after President Taylor’s death, President Woodruff made a trip to California and contacted Badlam.

President Woodruff also met with Col. Isaac Trumbo, grandson of LDS Pioneer John Reese, the man who had founded a town called Mormon Station in Carson Valley on the California-Nevada border. Trumbo had lived in Utah and still had significant business interests and connections there as well as in California. Would Badlam or Trumbo be willing to raise their voices on behalf of the Latter-day Saints?

The two men promised to enlist the help of California’s powerful senator, Leland Stanford, into whose hands much of Samuel Brannan’s fortune had fallen and who had visited Utah in 1869 to drive the “golden spike.” It was hoped that Stanford respected the Saints enough to raise his voice on their behalf. Badlam and Trumbo promised to promote Utah statehood among national Republican leaders and even went to Washington under assumed names to lobby for this cause. [1]

In April 1889, President Woodruff took further action. He brought a prominent group of Latter-day Saints to California, where Badlam and Trumbo arranged two meetings with Senator Stanford. Though these visits were crucial events in Latter-day Saint history, little is known about their details. President Woodruff described Stanford as “a good friend of ours,” who was ready “to do everything in his power for our good.” [2]

Shortly after President Woodruff’s return to Utah, the Church ceased authorizing new polygamous marriages and dismantled the adobe Endowment House where they had been performed. To emphasize this new position, President Woodruff issued a sworn statement dated 24 September 1890 that became known as the “Manifesto.” It was subsequently canonized into Latter-day Saint scripture (Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 1).

Although a few felt that their leaders had “sold out” to government demands, President Woodruff testified: “The Lord showed me by vision and revelation exactly what would take place if we did not stop this practice. . . . I went before the Lord, and I wrote what the Lord told me to write.” [3] Truly, Wilford Woodruff’s vision was a turning point, not only for the Saints in California, but for the Church as a whole.

Over the course of time, Mormonism cooled as a controversial issue. The press, which had used plural marriage to make the Church a whipping post, instead began to recognize in the LDS people some of the virtues then being advocated by the American Populist movement—industry, thrift, temperance, and self-reliance.

A little more than two years later, the government was convinced that sufficient time had passed to prove the Church’s good intentions, so it issued a proclamation of amnesty to all those who had entered into polygamist relationships before 1 November 1890. Soon afterwards, the government returned the Church’s confiscated property. A new climate of goodwill resulted as the Saints and their fellow Americans genuinely desired to tolerate one another. Utah was finally admitted to the Union in 1896.

The First Presidency also shifted the Church’s longstanding emphasis on gathering to Utah. During the 1890s, the Church began encouraging its members to remain in their homelands, to gather others about them to help build local branches, and eventually to organize wards and stakes there. This new emphasis had been anticipated in Joseph Smith’s revelations which specified that the time would come when the Saints would gather in more places than one (D&C 101:20–22; 115:17–18). In this context, and with the issue of polygamy resolved, the Church returned to California.

Sharing the Gospel in Oakland

The new beginnings in California developed around families and individuals who had fled from Utah to avoid government persecution. In fact, by the time President Woodruff issued the Manifesto, a permanent presence of Church members in California was already established.

Norman Phillips, one of the original six members in a newly formed Oakland branch, who for over twenty-three years served as clerk and then as president in the first permanent branch in the state, left an account of these beginnings. According to his record, it began in July 1890, two months before the Manifesto was issued, when Mark Lindsey, his wife, and two children arrived in Oakland as polygamous refugees from Utah. Although a few other members of the Church were in the city, Lindsey was unaware of them.

One morning, Lindsey saw a man walking in front of him whom he felt impressed to follow. This individual turned out to be Bishop Cutler from Lehi, Utah, also in hiding for plural marriage. Cutler knew of others in San Francisco and Oakland who were “on the underground,” and he and Lindsey immediately began visiting them.

In Oakland they found John Pickett, through whom they learned of Alfred and Charlotte Nethercott. The Nethercotts were among those whose spiritual home during the Church’s absence had been the Reorganized Church. However, they did not feel entirely comfortable there and, after repeated warnings to stop preaching the doctrines of the “Utah Mormons,” they were excommunicated from the RLDS Church.

Alfred Nethercott then wrote to Salt Lake City requesting readmission into the LDS Church. As a result, Lindsey and Pickett visited the Nethercotts and on 5 December 1890 baptized them in the ocean, together with their son, Charles, and his wife, Rebecca. President Woodruff subsequently sent Lindsey and Pickett written authorization to act as missionaries. By January 1891 there were thirty-six members of the Church in the Oakland area. [4]

Norman Phillips was one of those whom Alfred Nethercott had earlier converted to the Reorganized Church. After moving to Southern California, Phillips was contacted by Lindsey, who had been sent by the Nethercotts. After about a month of studying with Lindsey, Phillips was baptized despite the objections of his wife, who said, “If you get baptized into that Mormon Church I will never live another day with you!” A few months later she left, and after trying for four years to convince her to return, he divorced her and remarried. He returned to Oakland, only to find that the Nethercotts had all moved to Utah, which left him “all alone without the knowledge of another Mormon in the whole state.” [5] He evidently was not acquainted with any of the other Oakland members or with the Garlick family, who still held small meetings at their home in Sacramento. Pickett went to Utah and reported that there was enough interest in the Church in California that another missionary should be sent in his stead.

California Mission Reorganized

Based on Pickett’s report, on 10 August 1892, thirty-five years after George Q. Cannon had closed the doors to his California mission office in San Francisco and left for Utah, President Cannon, now a member of the Church’s First Presidency, participated in the decision to reopen a mission in California. Church leaders sent fifty-year-old Luther Dalton to organize and preside over local branch leaders and to supervise missionary activities. A resident of Ogden, Utah, he was born to Latter-day Saint parents in Nauvoo, Illinois, and crossed the Plains with them in 1852.

President Dalton held his first California meeting on Sunday, 28 August 1892, at the home of James Jorgensen in Fruitland (or Fruitvale), an Oakland suburb. [6] Jorgensen had recently been rebaptized. Two weeks later, Dalton rented a fraternal hall on Washington Street between Thirteenth and Fourteenth Streets, distributed hundreds of circulars advertising the meetings, and rebaptized several members.

On 2 October 1892 Dalton organized the Oakland Branch (which also encompassed San Francisco) as part of the Alameda Conference, which had jurisdiction over all of Northern California. The branch had six members, including the following officers: Joseph Natress, president; Dr. John Peter Phillip Van Denbergh and James Peter Jorgensen, counselors; and Norman B. Phillips, clerk. The other two branch members were the wives of Brothers Van Denbergh and Jorgensen. [7] All lived in Oakland except the Van Denberghs, who lived in San Francisco.

Two weeks later they decided to hold two meetings each Sunday, and their intentions were advertised in the San Francisco Examiner, the successor to the California Star. However, attendance was small, and the rent, fifteen dollars per month, seemed too high; therefore, they moved to the Thomas Hall at 11561/

Meanwhile, on 27 November the sporadic little branch in Sacramento was also officially reorganized with Aaron Garlick as president. Hence, Oakland and Sacramento may claim the honor of having the longest-standing Church units in California. As this memorable year ended, four missionaries were sent to assist President Dalton: Henry B. Williams and George H. Maycock were assigned to revitalize the faith of the Saints in Southern California, and Alva Keller and James B. Cummings were assigned to do the same in Sacramento.

As anticipated, the missionaries soon found other Church members and sympathizers whose faith, without the benefit of the Church organization, had grown lax. In the north was an actor, Luke Cosgrave, who in 1890 brought a small stock company from El Paso and traveled throughout Northern California staging one-man Victorian road shows. There was also Brooklyn Saint Sophia Patterson Clark King. In Sacramento, in addition to the Garlicks, there were Dr. Ward Pell (possibly the Brooklyn Saint or his son), Frederick Merriweather, and Archibald Curie.

In mid-1893, before President Dalton had been in California a year, the Oakland Branch with thirty-eight members split and created a dependent Sunday School in San Francisco. There were also twelve members in San Bernardino, twelve in Los Angeles, eight in San Diego, and thirteen others scattered about, making a total of eighty-three. By the end of that year, the number had grown to 120. President Dalton returned home in February of the following year, after eighteen months of service.

Karl G. Maeser returned to preside over the California Mission for the brief period of January to August 1894. As the Superintendent of Church Schools, he was sent primarily to arrange and direct an educational exhibit for the Church at the San Francisco Mid-Winter Fair. “The exhibit made by the Mormon schools of Utah is a very interesting and attractive one,” Campbell’s Illustrated Magazine of Chicago reported. “The work done by pupils in this display is, if anything, far superior to that shown in other exhibits, and speaks well for the system of education prevailing among the disciples of Brigham Young.” [8]

Brother Maeser established mission headquarters at 29 Eleventh Street, San Francisco. He immediately began advertising and holding public meetings at this location. He also addressed small congregations and hosted several General Authorities who came to visit the fair or who were en route to assignments elsewhere. This gave these top Church leaders a firsthand look at the newly reestablished Church in California.

On 6 April 1894 the first conference of the California Mission since the renewal of activities was held. A number of fair visitors attended. When the fair ended, President Maeser returned to Utah disappointed, believing that during his eight months as president progress had been imperceptible—not a single person had been baptized. The first convert baptisms did not take place until January 1895, twenty-eight months after the mission was reopened. However, President Maeser’s public-relations efforts resulted in a friendlier atmosphere.

On 25 July 1894 Henry Tanner, a twenty-five-year-old future attorney, replaced Karl G. Maeser. He almost immediately became ill with what he thought was a recurrence of the malaria he had contracted as a missionary in the southern states. By the time the proper diagnosis of typhoid fever was made, the doctor said he did not have much chance of living. The Saints called a special prayer meeting for him, choosing Brother Charles Nethercott, who had returned to the Bay Area, to offer the prayer. Branch clerk Norman Phillips described this as

one of the most eloquent prayers in behalf of the sick that I have ever heard. . . . During and after that prayer there was the greatest outpouring of the spirit of God that I ever saw. When we rose from our knees, there was not a sad face, not gloom in the building. The spirit testified to us each and all that all would be well with Brother Tanner, that he would get well and be amongst us again shortly, notwithstanding the unfavorable report given by the doctors. I will never forget that meeting. . . . The doctors were surprised at his rapid recovery; in fact they were surprised at his recovering at all. [9]

The little branch in Oakland was soon moved to San Francisco, where Dr. Van Denbergh provided for a time rentfree quarters for both the mission president and the branch. However, growth was slow until 1895, when they moved the meeting place to 909 Market Street and erected a small sign on the busy street advertising their meetings. “From that time on the branch began to grow.” [10] Soon afterwards, the San Francisco Call carried the following:

TO REDEEM THE GENTILES Mormonism Makes its Eirst Strong Effort To Plant Itself Here Many Missionaries at Work Not Gray-Whiskered Fellows, but Nice Young Business and Professional Men [11]

Growth in the South

In the early days, most of the Church’s activity in California was concentrated in the north. However, things were happening in Southern California that would alter the face of the state and the Church.

Los Angeles was not a major focal point in early Church history, with the exception of the quartering of a Mormon Battalion Company which built Fort Moore in 1847. Nor had it been a leading California city, even though it was one of three Spanish pueblos (towns associated with missions) existing since early Spanish colonial mission times. Also, Los Angeles did not have a deep-water port and thus was not a major town until connected by rail. In 1887, the population was only eleven thousand, the same as it had been ten years earlier.

In that year, however, the Santa Fe Railroad completed a line from Kansas City to Los Angeles. A government survey in the 1850s determined that the only way for a rail line to enter Southern California was through a tunnel into the top of West Cajon Canyon, but the Southern Pacific owned the necessary approaches, hence blocking the entry of any rival. However, Fred T. Ferris, an LDS convert from Australia and a San Bernardino resident (for whom the town of Perris was later named), showed how the Santa Fe could enter “through the eastern wing of Cajon Pass never before considered feasible.” [12]

A memorable fare-war broke out with the Southern Pacific Railroad, which had earlier built a line down from San Francisco. As passenger fares from the Midwest plummeted from one hundred dollars to just one dollar, suddenly thousands of people who had long dreamed of going to the coast decided that now was the time.

Groups of families and friends, businesses, and farming associations made up traveling communities. The Southern Pacific alone brought 120,000 people in 1887. As these immigrants poured in, Southern California’s population mushroomed. The newcomers’ tents ringed the city much as they had in San Francisco when the Brooklyn arrived some forty years earlier. This avalanche of land boomers in Southern California matched the number that flooded into Northern California during the gold rush.

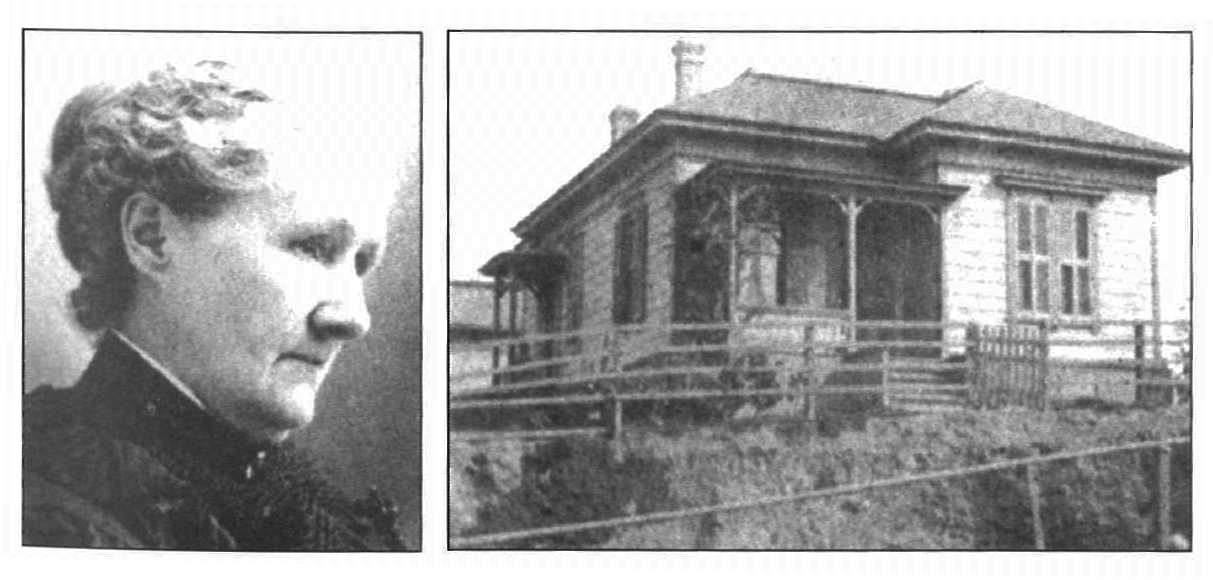

Latter-day Saints were caught up in this excitement. In July 1884 Eliza Woollacott had come to Los Angeles from Salt Lake City with her wine-merchant husband, two children, and two grandchildren. The Woollacott home, located at 220 North Grand Avenue, became the focal point of Church activity for many years. Eliza, whose gracious hospitality brought numerous Church dignitaries to her home, pleaded for missionaries to serve in her area and “wept with joy” when, in 1892, Elders Williams and Maycock were assigned to serve in Southern California. 13

Eliza Woollacott and her home in Los Angeles

Eliza Woollacott and her home in Los Angeles

On 20 October 1895, the first conference of Southern California members since 1857 was held in Los Angeles. A missionary, Elder Parley T. Wright of Ogden, Utah, was sustained as Southern California conference president. The Los Angeles Branch was also organized with bakery owner Hans C. Jacobson as its first president.

The Church was also growing in San Diego. In 1886, William Cooper, a Church member from Wirksworth, England, arrived to help build the famous Coronado Hotel and remained to become an important local builder and contractor. Three years later, on 2 June 1898, a branch was organized in San Diego at the home of Sister Amelia Jewell on First Street. Charles Hoag was chosen as the first branch president. This branch would have its ups and downs—sometimes flourishing, and sometimes lapsing into complete inactivity.

At the close of 1895, California’s membership had increased to over two hundred—nearly doubling in two years. Los Angeles now had the largest congregation in the state, with fifty-one members. San Francisco had forty-six, Sacramento twenty-nine, San Bernardino twelve, and San Diego nine. Though mission headquarters were still in the north, from this point forward the Los Angeles area would carry the state’s largest LDS population, swelling over the next century to more than a half-million members.

Noted Visitors

Even after the San Francisco Fair closed, Church leaders continued to visit California. Several notable visitors came in 1896, which happened to be the fiftieth anniversary, or “jubilee,” of the Saints’ first arrival in the area. On 9 February Elder Heber J. Grant of the Quorum of the Twelve spoke at a meeting [13] of the San Francisco Branch and attracted a crowd of about two hundred people—a good number given the fact that there were only a few Latter-day Saints in the city.

Two months later, the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir came to perform—only the second time it had left the Intermountain West. On 14 April the Choir, directed by Evan Stephens, presented a concert in Oakland’s First Congregational Church. There were also five concerts in San Francisco. One of those was a Sunday service before an enthusiastic audience in Metropolitan Hall. Elder Grant spoke to the congregation in his second major San Francisco address in two months. “One could see the expression on their faces as we sang and he preached,” one Choir member recalled, “and we choir members thanked God for him and that we were partakers of that memorable occasion.” [14]

On 20 and 21 April the Choir performed in San Jose and in Sacramento.

The press, which until recently had maligned the Church, gave favorable reviews of the Choir’s performances. The San Francisco Call raved: “It is impossible to describe the precision of attack, the general fidelity to key, or the noble manner in which the singers respond to the slightest movement of the leader, who plays upon them as if they were mechanical.” [15] According to the Sacramento Bee, “the singing of the choir was indeed a revelation to lovers of choral music and an event long to be remembered.” [16] The Choir’s appearances undoubtedly created additional goodwill toward the Latter-day Saints.

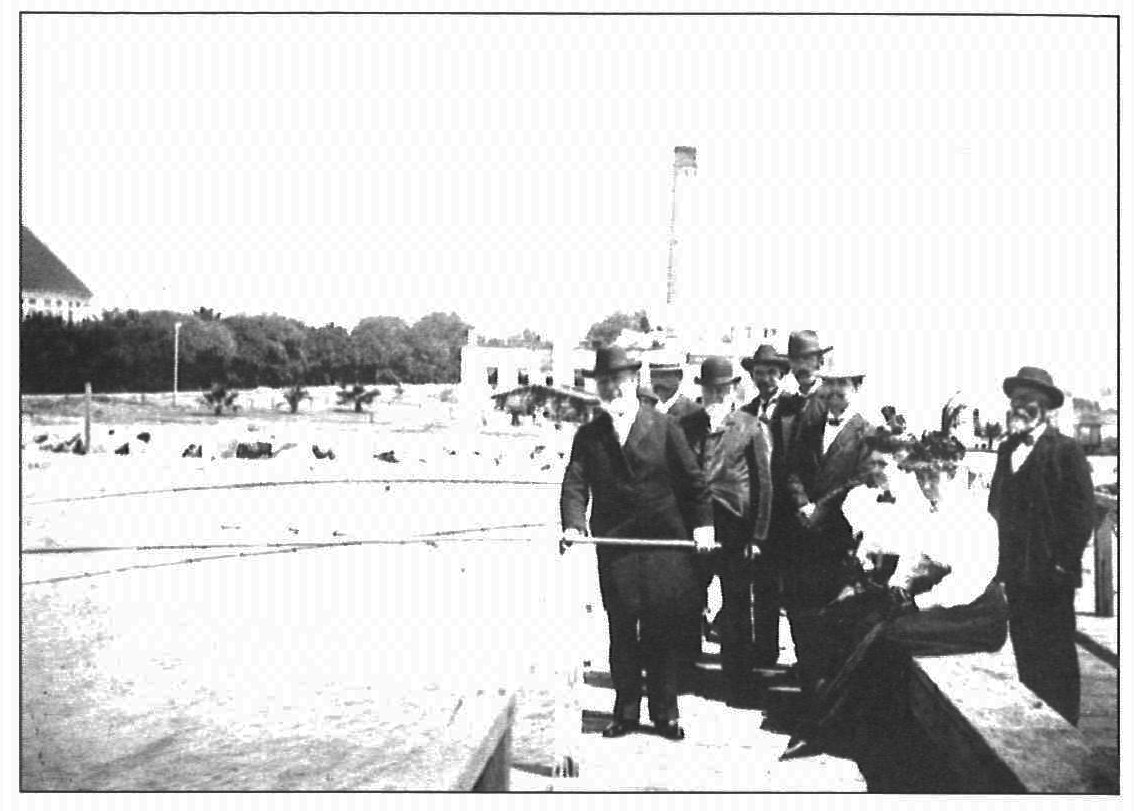

In June 1896 President Joseph F. Smith, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, and Elder Abraham H. Cannon of the Quorum of the Twelve spent three days with the San Francisco Saints. Lorenzo Snow, President of the Quorum of the Twelve, visited them on 9 August with his wife and two daughters. President Wilford Woodruff and his First Counselor, George Q. Cannon, spent two weeks in California later that month. The Golden State was obviously being closely observed.

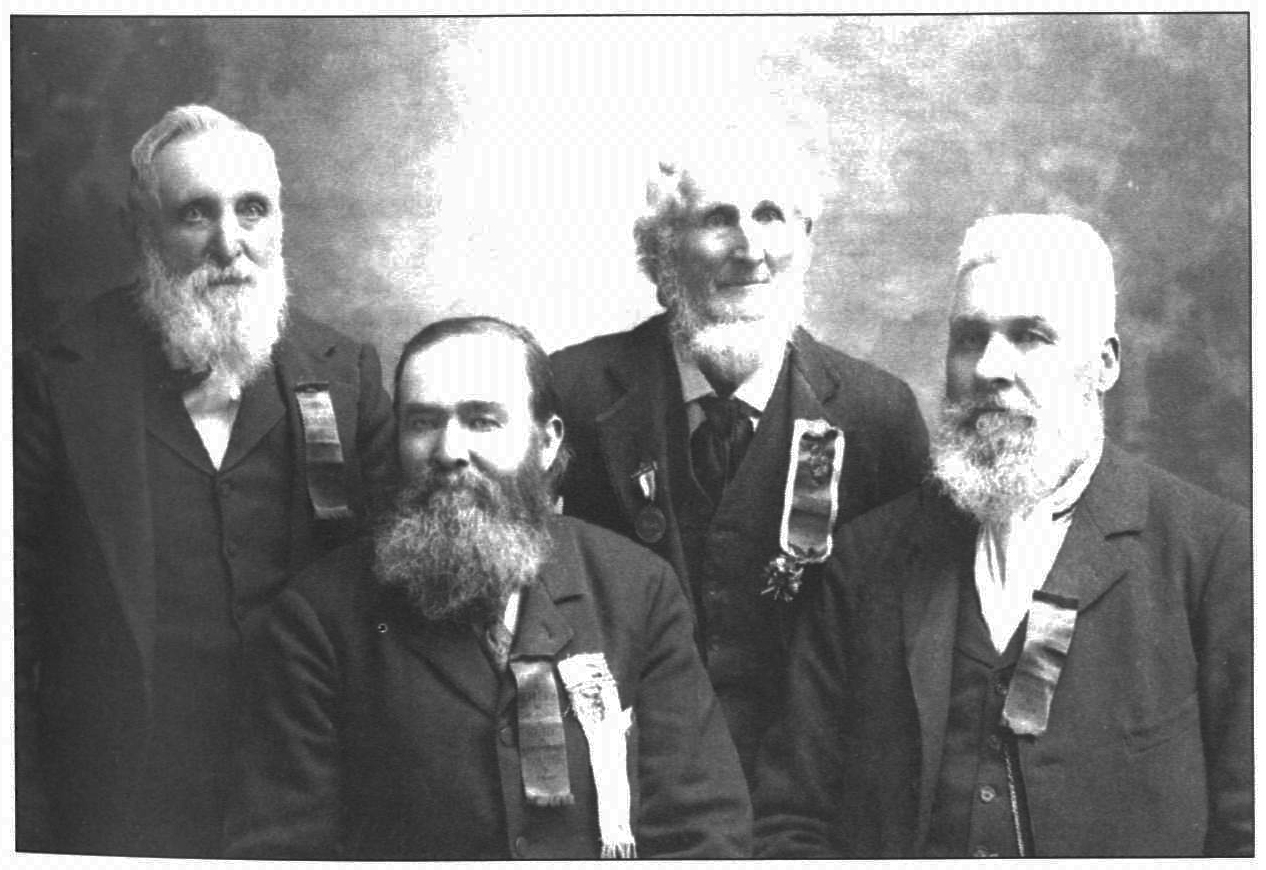

Wilford Woodruff (third from the left) and George Q. Cannon (left)

Wilford Woodruff (third from the left) and George Q. Cannon (left)

fishing from the Coronado pier in San Diego

In November, President Henry Tanner was released. During his administration, missionaries had been dispatched to organize branches at Stockton, Los Angeles, Fresno, Santa Cruz, San Bernardino, and the gold country town of Latrobe.

Growth continued as earlier members were identified and others moved into the state. By 1897, under a new mission president, Ephraim H. Nye, California Church membership doubled again to well over four hundred.

In 1897, the Improvement Era began publication; for many decades it was the official voice of the Church. To Californians living away from Church headquarters, the words of the prophets and apostles on the pages of this monthly magazine were particularly appreciated and bolstered their commitment to live the gospel though surrounded by those not of their faith.

Soon after it began, the magazine carried, over a three-year period, a series of articles written by John Horner describing the Brooklyn’s voyage and his role in early Latter-day Saint affairs in the San Francisco Bay Area. [17]

In 1898, Californians commemorated the discovery of gold. Four of the Mormon Battalion veterans who had been at Sutter’s Mill when the discovery was made were able to attend the celebration. Henry W. Bigler, Azariah Smith, William J. Johnston, and James S. Brown were honored by the Society of California Pioneers, which sponsored the celebration. The four veterans led a parade as “the only survivors of that notable occasion, fifty years before.” [18] This event generated “much favorable publicity” for the Latter-day Saints. [19]

Gold discoverers (from left to right): Henry W. Bigler, William J. Johnston,

Gold discoverers (from left to right): Henry W. Bigler, William J. Johnston,

Azariah Smith, and James S. Brown at 1898 jubilee

Notable Deaths in California

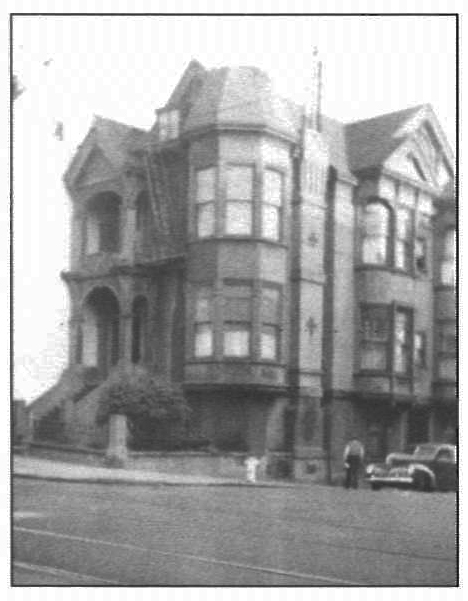

During the summer of 1898—the jubilee year of the gold discovery—ninety-one-year-old President Woodruff made another trip to California, this time to recuperate from his lingering asthma. He was accompanied by his wife Emma, President George Q. Cannon and his wife, Bishop Hiram B. Clawson and his wife, and his secretary, L. John Nuttall. Upon arriving in San Francisco on 14 August, President Woodruff and his wife became guests at Colonel Trumbo’s home.

Isaac Trumbo home in San Francisco

Isaac Trumbo home in San Francisco

On the following Sunday, 21 August, President Woodruff addressed the Saints in the San Francisco-Oakland Branch, speaking for about twenty minutes. This was his last public address. Two days later he underwent surgery. He was well enough by the end of the week to attend a dinner in his honor at the exclusive Bohemian Club. A few days later, however, he took a turn for the worse and died peacefully on 2 September at the Trumbo home. [20] President Cannon, who had recorded significant San Francisco events in the pages of the Western Standard nearly fifty years before, meticulously recorded the following recollection of the prophet’s death:

I arose about 6 o’clock. The nurse told me he had been sleeping in the same position all the time. I took hold of his wrist, felt his pulse, and I could feel that it was very faint. While I stood there it grew fainter and fainter until it faded entirely. His head, his hands, and his feet were warm and his appearance was that of a person sleeping sweetly and quietly. There was not a quiver of a muscle nor a movement of his limbs or face; thus he passed away. [21]

The Church leaders, their wives, Sister Woodruff, and Colonel Trumbo accompanied the body back to Salt Lake City. The journey was made in a special car provided by the Southern Pacific Railroad. President George Q. Cannon also died in California three years later, in April 1901, at Monterey.

These deaths near the end of the century marked the end of an era. The reopening of the Church in California was no mishap; it was a vital step in planting the kingdom of God in new areas of the United States and the world. It was now acceptable for a Latter-day Saint to live in the Golden State. This acceptance provided valuable experience in establishing the Church in predominately non-Latter-day Saint cultures outside America’s Intermountain West.

Notes

[1] Thomas G. Alexander, Things in Heaven and Earth: The Life and Times of Wilford Woodruff A Mormon Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1991), 249–50.

[2] Quoted in ibid., 252.

[3] Deseret Weekly News, 14 November 1891.

[4] Norman 13. Phillips, “History of the California Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” MS; Oakland California Stake Collection.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Some recall these early meetings as being in a parlor at 525 Sixth Street.

[7] Luther Dalton to the Deseret Weekly News, quoted in Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 305–6.

[8] Quoted in Alma P. Burton, Karl G. Maeser: Mormon Educator (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1953), 62.

[9] Phillips, 12.

[10] Ibid.

[11] San Francisco Call, 10 June 1895, excerpted in Leo J. Muir,/

[12] E. Leo Lyman, Guidebook: Mormon Historical Sites in the San Bernardino Area (Lyman, 1991), 12–13.

[13] Muir, 108–9.

[14] Quoted in J. Spencer Cornwall, A Century of Singing: The Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1958), 70.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Improvement Era 7, no. 7 (May 1904): 510–15; 7, no. 8 (June 1904): 571–75; 7, no. 9 (July 1904): 665–72; 7, no. 10 (August 1904): 767–72; 7, no. 11 (September 1904): 849–54; 8, no. 1 (November 1904): 29–35; 8, no. 2 (December 1904): 112–17; 9, no. 10 (August 1906): 794–98; 9, no. 11 (September 1906): 890–93.

[18] James S. Brown, Life of a Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Geo. Q. Cannon & Sons, 1900), 515.

[19] Campbell, 333.

[20] Alexander, 329–30.

[21] Quoted in Preston Nibley, The Presidents of the Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1959), 133.