The Golden Sun Sets: 1850

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 143–66.

Some eighty-nine thousand “forty-niners” had increased California’s population tenfold since the previous year. Another eighty-five thousand in 1850 nearly doubled it again. Initially, most were stricken with “gold fever,” described vividly by one forty-niner:

A frenzy seized my soul; houses were too small for me to stay in; I was soon in the street in search of necessary outfits; piles of gold rose up before me at every step; castles of marble, dazzling the eye with their rich appliances; thousands of slaves bowing to my beck and call; myriads of fair virgins contending with each other for my love . . . were among the fancies of my favored imagination. [1]

Beginning with the late arrivals in 1849, however, newcomers found more disappointment than gold. California had been exhaustively explored. The heaviest concentrations of gold had been mined out and the choicest land claimed. Many wished they had never come and therefore beat hasty retreats. One man wrote home that “many curse the day they ever started. They are not very satisfied with small wages and are inclined to run around just as we before them have done to our sorrow, and they will learn so.” [2] Another spoke of talking with an industrious friend who had been doing well back home:

“Why did you come here?” I asked. “Did not all our letters discourage further emigration?” “Yes, . . . but we thought that as so many were getting rich, they only wrote such letters to keep others away.” [3]

Now enough discouraging messages filtered “back home” that the traffic to California slowed. People began to come back to reality. By the latter part of 1850, immigration had ebbed, and normalcy in governmental and Church affairs began to emerge.

Two Latter-day Saint apostles were in California to work in the interest of the Church and its members. Additionally, several other Latter-day Saints played key roles in California’s transition from gold-mining frontier to statehood. One of those was John Horner.

California’s “First Farmer”

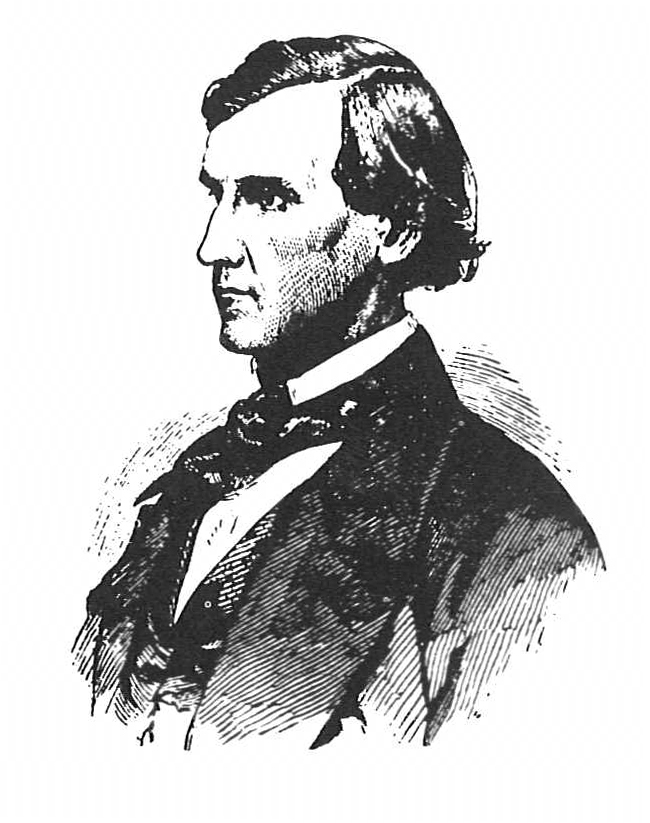

John M. Horner and his wife, Elizabeth, came to farm—a trade which they had learned in their native New Jersey. Almost as soon as the Brooklyn landed, Horner rode around the Bay looking for the most favorable locations. After a brief try at sharecropping near present-day Antioch, John and Elizabeth struck out on their own. In March 1847, they located permanently in the shadows of Mission San Jose, in present-day Fremont, about twenty-five miles northeast of the city of San Jose. They were the first Anglo family to build a home in what is now Alameda County, and they became the parents of the first Anglo baby born there.

John Horner

John Horner

While teaching school in New Jersey, Horner worked after hours to raise potatoes in a few unused corners of his father’s corn field. He sold his crop for five dollars just before sailing on the Brooklyn and used this money to buy a pistol to defend himself in the “savage” country to which he was going. After arriving in California, he carried his gun for protection wherever he went. “But,” Horner later recalled, “seeing no one whom I wanted to shoot and no one who wished to shoot me, I concluded my pistol was useless and traded it to a Spaniard for a yoke of oxen, the first animals I ever owned.” With this team he launched what became a multimillion-dollar farming enterprise. [4]

Having been told there was a market for grain among Russian seamen, Horner planted grain and vegetables in the spring of 1847, only to have the entire crop destroyed by insects. His fall crops were again destroyed—this time by wandering cattle. The next spring, when the Homers learned that gold had been discovered, they went briefly to seek their share in the mines. But they found that selling food was more profitable than mining gold. Miners had to eat, and they could not eat gold.

The Homers returned to their farm and planted vegetables in the fall of 1848. When the real gold rush came in 1849, they were among the few who could supply fresh produce, which skyrocketed to such prices that they, like Brannan, became wealthy in a single season. They had such a flair for farming that at the height of their prosperity, they acquired and fenced several thousand acres and employed as many as 150 men. “I fully realized that I must rely upon myself and the Great Father for success,” Horner reflected. “Industry, honesty, and perseverance were my guiding stars.” [5]

Building the Latter-day Saint community to the point where there was talk of organizing a stake, Horner, with his wealth, encouraged and helped many Latter-day Saint settlers in and around Mission San Jose. He allowed members to settle on his properties, gave them the use of land, teams, and machinery, and sold their produce on commission. In a central location he built a schoolhouse and employed a teacher. This building also served as a social hall and on Sundays as a meetinghouse. It therefore may be regarded as the first Latterday Saint chapel in California.

On Sunday mornings, Horner allowed the Methodists and Presbyterians to use his meeting house. In the afternoons, he personally preached to Latter-day Saint congregations of thirty to forty worshipers. [6] The building was moved several times, remaining intact until 1965 when it was burned in a fire drill.

Horner also encouraged several of his New Jersey kindred to join him and provided financial means whereby they could do so. He and his associates introduced new agricultural methods, being the first to employ “the modern mould-board plow; the first cradle for cutting grain; the first mowing machine, and the first reaping and thrashing machines ever used in California.” [7] At California’s first agricultural fair, which was held in 1852, he was lauded. He was the largest contributor, received the highest awards, and was given the official title of “First Farmer of California.” He was the foremost pioneer of the state’s largest industry.

Horner continued farming for many years. In addition to building a school/

John Horner's schoolhouse/

John Horner's schoolhouse/

San Francisco Becomes a City

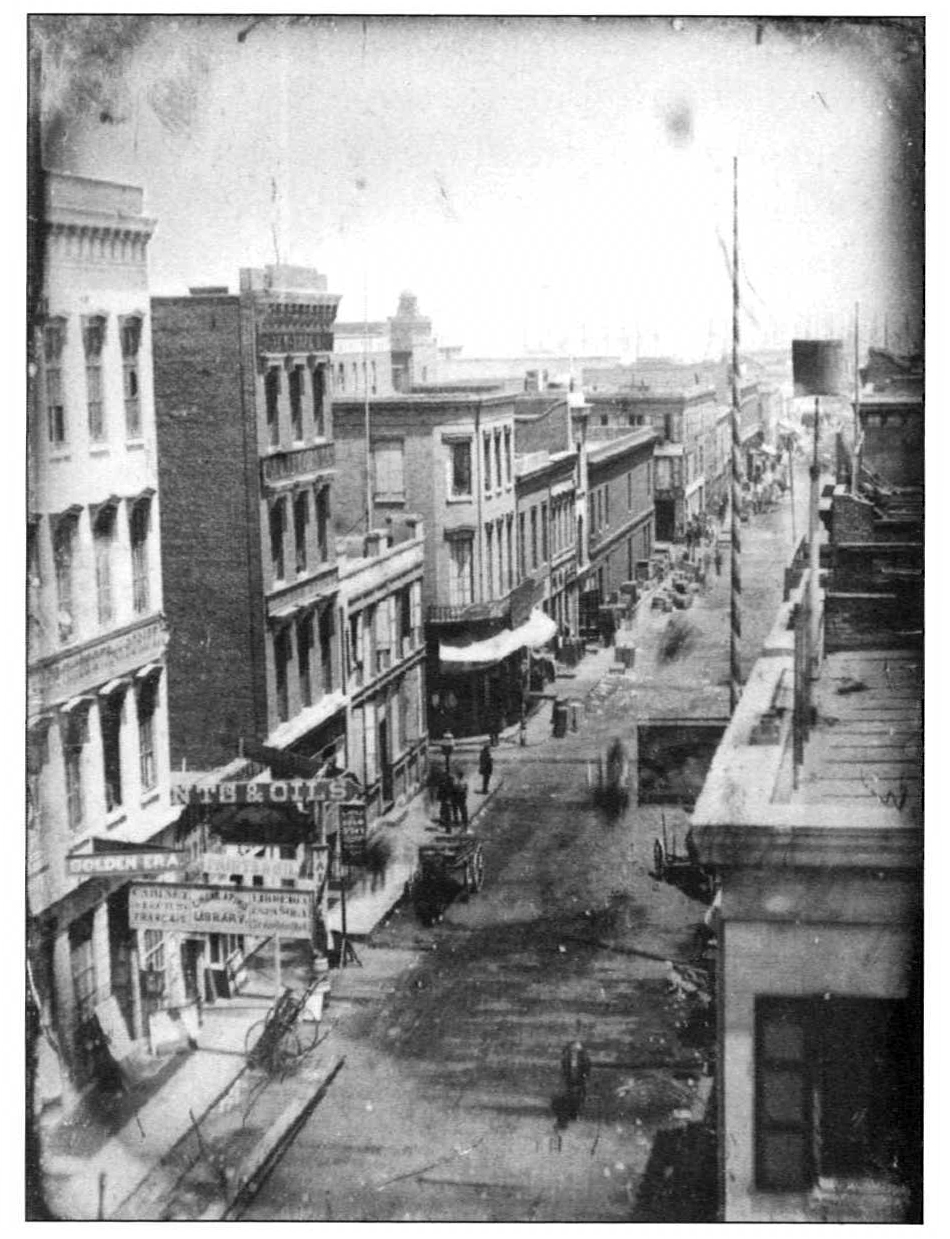

In San Francisco, the old Mexican forms of administration were replaced by an American-style government. The city also took on a cosmopolitan atmosphere, populated by some of the world’s brightest young men, flexible adventurers not afraid to take risks. Many were northeasterners who built the city on the Brooklyn colony’s foundation of New England attitudes and styles. But what had once been a Latter-day Saint majority was now less than 5 percent of the population.

In three years the city had grown from a population of less than five hundred to thirty thousand, with only about two thousand of them female, including many prostitutes. There were forty-four steamers employed in river trade, twelve oceangoing steamers, seven daily newspapers, sixty brick buildings, and eight or ten first-class hotels. There were 107 miles ofstreets (seven miles planked), and most of that distance was properly sewered. Red flannel shirts and Levis (a San Francisco invention) were being replaced by white linen shirts, top hats, and wool trousers. Brannan’s “long wharf” was now a focal point of commerce, and over its wooden-planked surface vehicles thundered almost constantly.

San Francisco in 1851

San Francisco in 1851

In August 1850, a group of early settlers formed the Society of California Pioneers, a socially prominent organization in San Francisco for many years, in which those who had come to California before 1 January 1849 formed the first rank. Samuel Brannan was elected as one of the three original vice presidents. [8]

During 1850 devastating fires continued. On 4 May a fire raged for seven hours destroying three hundred houses, the City Hall, and three important business blocks adjoining Portsmouth Square. The loss was over four million dollars— equal to half the value of all the gold mined in California the previous year. Almost immediately steps were taken to rebuild the city. Just forty days later, however, another fire burned the business district from Kearny Street to the waterfront, causing another three million dollars damage. The extent of Samuel Brannan’s personal losses in these fires is not known, but they must have been considerable, since his holdings were extensive.

In addition to Brannan’s enterprises in San Francisco and Sacramento, he was also involved with the development of Yuba City and perhaps Marysville, located some forty miles north of Sacramento. One observer noted that in Marysville “you will see the go-ahead-iveness of the Yankee nation. In one fortnight’s time $25,000 worth of lots at $250 each were sold. In ten days . . . seventeen houses and stores were put up, and what was before a ranch—a collection of Indian huts and a corral for cattle—became a right smart little city.” [9] This pattern of development was repeated many times.

Elders Lyman and Rich in the North

When Elder Charles C. Rich left the Salt Lake Valley during the fall of 1849, the First Presidency gave him a letter of introduction which also instructed him to “consult” with Elder Amasa M. Lyman relative to the interests of the Church in California, to gather tithing, to receive donations for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund (a fund from which the poor could borrow money to help them immigrate to Utah, then repay it when they were settled and employed), and “to preach the gospel as he had opportunity.” [10] The First Presidency also sent Elder Lyman instructions regarding Latter-day Saint settlement in “Western California,” a term being used by Church officials to encourage the combining of California and the Great Basin (called “Eastern California”) into a single state: “We wish you and Brother Rich to take into consideration the propriety of continuing to hold our influence in Western California by our people remaining in that region. Our feelings are in favor of that Policy unless, all the offscouring of Hell has been let loose upon that dejected land, in which case we would advise you to gather up all that is worth saving and come hither with all speed.” [11]

After their brief rest at the Williams Ranch in Southern California, Jefferson Hunt and others left on 12 January to escort Elder Rich northward. They followed the coastal road via the California missions, the same route Hunt had traveled with the Battalion dischargees two and one-half years earlier.

As the group stopped in San Jose during a legislative session, Addison Pratt, one of those in the party, visited with New Hope foreman William Stout, who was operating a boarding house. “He boasted about the immense riches he had obtained since he had arrived in California. But when I made our circumstances known to him, he began to plead poverty, that he was in a lawsuit with his wife, that she had robbed him of some thousands.” [12]

Like so many others, Stout either flagrantly exaggerated or found his California gold slippery. Pratt noted that when it came to helping missionaries, “as a general thing, those that 1 supposed had accumulated the least gold, were the most liberal towards us.” [13]

Elder Rich’s party reached San Francisco on 15 February, where, according to Addison Pratt, Brannan had told the local Saints that during his 1847 visit with Brigham Young he had promised to pay at a later time the two or three thousand dollars he had collected. However, in conversations with the First Presidency, Pratt had not heard of any such promise. Furthermore, he claimed Brannan never sent President Young the “thirty percent money” he collected from the Latter-day Saint gold miners.

Addison Pratt wrote that Brannan had accused him of standing in the way when Brannan was about to “make a ‘heap’ of money for the church” by increasing the value of several lots Brannan owned. According to Pratt, Brannan proposed that the Church build “an adobie Temple” worth some twenty-five or thirty thousand dollars. As an incentive, he promised to give the Church a quarter of the lot. Pratt wrote:

I had seen enought of his tricks to believe he would manage the agreement so that the least failure on the part of the church would forfeit their claim to it, and it would fall back into his hands. . . . [T]he Spirit that was in me moved me to come out against it. And I now suppose that he tries to make Br. Lyman think that had I held my peace, the church would now be in possession of one fourth of a lot that would be worth from 25 to a 100,000 dollars. But I have no such notion about the matter. For he had been verry anxious to help the church, he would have long ago handed over to Br. Lyman the money that he has already swindled off of the brethren. [14]

Meanwhile, about one week before Elder Rich’s arrival in San Francisco, Amasa Lyman sailed to Los Angeles, hoping to intercept his fellow apostle. When Elder Lyman arrived at San Pedro and heard that Elder Rich had already headed north, he returned to San Francisco, arriving on 13 March. But Elder Rich had left by that time for the Mariposa mining district.

On 1 April Elder Lyman took a steamer up the Sacramento toward the gold fields, stopping at Benecia on the way. Coincidentally, Elder Rich landed there about the same time, and the two were united. Elder Lyman, who had been anticipating Elder Rich’s arrival for nearly a year, wrote: “To strike hands in California with a man having faith in God is a real treat, like a fruitful flower in a parched land.” [15] Both then continued on together to Sacramento. Two days later they left the new Brannan-Fowler hotel to accompany the Huffaker wagon train to Greenwood, where hundreds of Latter-day Saints were gathering.

On 10 April they selected a site in San Francisco, “on Br. Lincoln’s land,” for a chapel. A few days later they appointed Ward Pell and George Sirrine as “agents” to raise money for the project. [16] Pell was one of those whom Brannan had excommunicated, but he apparently remained close to the Church. No further record has been found of this chapel.

During those weeks, Addison Pratt and James S. Brown prepared to leave on their missions to Polynesia. On 12 April Elders Lyman and Rich spent the day instructing them and setting them apart. “The brethren at San Francisco put forth the helping hand to assist us in getting started away from there,” Addison Pratt gratefully acknowledged. The missionaries set sail nine days later. [17]

One of the apostles’ most difficult assignments was to visit Samuel Brannan and obtain from him the tithing he had supposedly collected in the name of the Church. Elder Lyman and Porter Rockwell had already visited Brannan for this purpose in January. No contemporary record of this confrontation has survived, but Sutter later wrote that when they asked Brannan for the Lord’s tithes he retorted in disgust: “You go back and tell Brigham Young that I’ll give up the Lord’s money when he sends me a receipt signed by the Lord, and no sooner.” [18] Elder Lyman saw Brannan once again, about a month later, but with no better results.

The apostles had more success on 28 June when they visited Brannan together. Amasa Lyman’s diary recorded that Brannan “made me a present of $500.00 made an arrangement for the books in his possession,” [19] perhaps suggesting the end of Brannan’s five-year Church leadership role at the age of thirty-one. Was the five hundred dollars a pittance, or was it generous in the aftermath of the losses Brannan sustained during the recent devastating fires? Three days later, Elder Lyman dined with Brannan, possibly to pick up the promised books.

This is the last record of Brannan giving any funds to, or having any involvement with, the Church or its leaders. However, he was generous to various charitable causes and had been known to assist individual Latter-day Saints locally. Now, Elder Rich reported that Brannan confided that as far as the Saints were concerned he “stood alone and knew no one only himself and family.” [20] All the references to Brannan in Amasa Lyman’s diary use the title “Mr.” in contrast to the more familiar “Brother” used in reference to faithful Church members— a further reflection of Brannan’s estrangement. Still, the two apostles did not choose to cancel Brannan’s Church membership. [21]

Along the California Trail

Meanwhile, during the spring, a few more Latter-day Saint pack or wagon trains left Salt Lake City for the gold country. At this time of year travelers preferred the northern route, known as the California Trail. First to leave, on about 3 April, were men assigned to carry mail to Northern California. Accompanying this small group was sixty-two-year-old Solomon Chamberlain, who had been a faithful Church member since 1830, the year of its organization. Traveling on horseback, they quickly crossed the deserts and even the Sierra Nevada snows, arriving in Sacramento by 22 June. [22]

Later in April, Thomas Orr headed another group of thirty-five families in wagons. They were held up for three weeks by the snow which the horsemen had more easily negotiated. While camped in the Carson Valley, they did some prospecting in nearby “Gold Canyon,” without finding much. One of them, Abner Blackburn, later observed, “If we had known [of] the rich mines higher up the canion, the outcome would be different. We mist the great Bonanza.” [23] He was referring to the Comstock Lode, the largest gold strike in North America, which fueled the area’s economy for the next fifty years. Latter-day Saints had another near-miss at the Comstock. The 1848 wagon train going to Utah had found gold in the vicinity but abandoned their search to travel on.

Orr’s party finally reached Pleasant Valley near Placerville on 4 July. Thomas Orr purchased a hotel at Salmon Falls on the American River, a few miles above Mormon Island. He enlarged the hotel, opened a bakery, and soon was taking in as much as fifteen hundred dollars per day. He became a deputy sheriff, and his sons operated stagecoaches to Sacramento and Marysville. Remaining in the area until 1862, he raised his children as Latter-day Saints and often hosted missionaries who traveled through. [24]

On one occasion Orr encountered a former acquaintance, Porter Rockwell. When Orr called Rockwell by name, an alarmed Porter exclaimed that “his life would be worth nothing if the Gentiles knew who he was.” [25]

At April general conference in Salt Lake City, Hiram Clark was called as mission president to Polynesia. He and William D. Huntington were appointed to lead a company to California—some to assist Elders Lyman and Rich, some to serve with Clark in Polynesia, and others to mine gold. This was “the last known company of approved Mormon gold miners.” The group of thirty-nine “Mormons and non-Mormons” left Salt Lake City on 7 May. [26]

Traveling by carriage with this party were two sisters, Caroline Barnes Crosby, who was accompanying her husband on his Polynesian mission, and Louisa Barnes Pratt, who was to join her husband, Addison, already serving there. They were among the first female missionaries in the Church’s history, and both penned forthright accounts of their journeys to California. Louisa noted that their wagon train overtook another headed by Ephraim Hanks that had left three weeks before them, even though it “travelled on the Sabbath, [and] we have not.” [27]

She also described the hordes of starving gold seekers along the route, many in the same condition as the family Elder Rich’s party had assisted the previous fall: “Oh, the crowds that throng this highway, going in search of gold; crowding about our wagons to be fed. We must feed them either for pay, or without. They must have starved to death, had we not been here with provisions.” [28]

Although many were starving, there were places along the way where provisions were available. Caroline recorded that they passed “a trading post . . . a table set under a tree with liquors, groceries and provisions of almost all kinds . . . and houses made of posts set in the earth and covered with cloth looking very comfortable for summer.” [29]

Another trading post belonged to Louis C. Bidamon from Nauvoo, who lived in “quite an extensive house.” [30] Bidamon, who was not a Latter-day Saint, was married to Joseph Smith’s widow, Emma. He was among those who had left families behind to search for gold. Writing to Emma, he confessed that finding gold was not easy: “It is obtained by the hardest of labour, harder than my constitution is able to bear. The acquisition of gold in the mines is something like a lottery, there is sometimes large amounts . . . but these are few occurrences and far between.” [31] During the evening, he came to the missionaries’ camp, joined them in singing and prayer, and was “delighted with some of our hymns.” [32]

Descending from the mountains, the Clark-Huntington caravan met “a Mormon trading expedition” carrying supplies east to Carson Valley. With them was Solomon Chamberlain, who, finding he could not even mine enough gold to pay for his food, had seen enough of California after only about two weeks. Chamberlain later wrote: “I knelt down and asked the Lord in faith what I should do, and the voice of the Lord came unto me as plain as tho a man spake, and said, if you will go home to your family, you shall go in peace, and nothing shall harm you.” Leaving everything behind and telling no one where he was going, he set out across the mountains. He was convinced that his eventual safe return from California’s fray was a blessing from God. [33]

The First Presidency Sends Instructions

The missionaries arrived in California in July and carried letters of instruction from the First Presidency. In April the First Presidency had written at least two letters concerning California. Their 12 April “General Epistle” to the Saints on the subject of California migration complained that Saints frequently left or planned to leave the Salt Lake Valley without Church sanction. While “the greater portion have gone according to the council of their own wills and covetous feelings,” it was “not too late for them to do good and be saved, if they will do right in their present sphere of action.” The Presidency pointed out that “gold is good in its place—it is good in the hands of a good man to do good with, but in the hands of a wicked man it often proves a curse instead of a blessing. Gold is a good servant, but a miserable, blind, and helpless god, and at last will have to be purified by fire, with all its followers.”

California Saints were informed that Elders Lyman and Rich would continue to collect tithing, keeping a record “of all faithful brethren.” But they were also to keep a “perfect history of all who profess to be Saints and do not follow their counsel, pay tithing, and do their duty.” These were to be reported in every mail, that “their works may be entered in a book of remembrance in Zion.” [34]

The First Presidency directed their second letter, dated 23 April, specifically to Elders Lyman and Rich: “Gather up the brethren, if you have not already done it, and organize them, and preach to them and pray with them, and let them preach to each other and pray for each other, and observe the Sabbath and refrain from all evil, and they will have the spirit of God and rejoice therein.” [35]

The Presidency’s instructions to “preach to each other” were a shift from Brigham Young’s 1847 directive to curtail public preaching. Two days before delivering these instructions, even the missionaries felt it best to abbreviate their own meeting because “Brothers Rich and Lyman we understood hold none here.” [36] One historian found little evidence “of any [public] preaching by the two” prior to the arrival of the “company of proselyting missionaries on their way to the Society Islands.” [37]

Now, however, the apostles wasted no time implementing the new policy and preached during the evening of the day on which they met the incoming missionaries. Louisa Pratt recorded in her diary that “to see their faces and hear their voices proclaiming the truth so far from home is comforting to the soul.” [38] Two days later, at a Friday evening function, the missionaries enjoyed singing hymns with the apostles and hearing from them a report of their activities during their previous year in California. [39]

On Sunday, 21 July, the apostles preached at Rockwell’s tavern. Caroline Crosby recorded: “We had a very good meeting in the afternoon. Brothers Rich and Lyman said a great many good things to us concerning our mission and also counseled those who expected to stop in California to abstain from the vices of the country, viz., gambling, drunkenness, and every other that can be named.” [40]

Louisa sold her faithful old carriage, the last piece of property that she and Addison had retained from their youth, and which had brought her and her sister to California. The two sisters then went on to San Francisco by boat and arrived there on 25 July. Louisa, finding the city less than immaculate, wrote: “Came down to the great city, that has made such a noise in the world. A great city it is, for the age of it, but so filthy it is dangerous for people to stop there.” [41] Still, the sister missionaries were warmly received. Louisa found Brannan’s mother-in-law, Fanny Corwin, to be “an exceedingly kindhearted woman full of faith and good works. She lived with her daughter in a house like a king’s palace.” They were also well received by Sister Morey, who “shared largely of her benevolence,” and by John Lewis, who transported them in his carriage to his home at Mission Dolores where they were hosted by the Saints for two weeks. “A better class of citizens never lived in San Francisco.” [42] The sister missionaries remained at Mission Dolores until 15 September when, after many difficulties and delays, they finally departed for Polynesia.

Elders Lyman and Rich Return Home

Among the tired, disillusioned miners, there was a growing sense of futility. Hiram Clark wrote to Brigham Young that most of the miners he met were “not doing much and a very poor prospect of doing better.” He asserted that “many of the boys here would give their old shoes to be back.” [43] “I am tired of mining and of the country,” Henry W. Bigler confided in his diary, “and long to be at home among the Saints.” [44] Charles C. Rich reported to Brigham Young that “the brethren in the mining regions who had come from Salt Lake Valley with the Gold Mission or later generally wished themselves back in the shelter of the mountains among the Saints.” He therefore anticipated “a general disposition to return home this fall which I shall encourage.” [45]

For several months, Elders Lyman and Rich had traveled together throughout the gold country visiting people, blessing the sick, arranging Church business, collecting tithing, and counseling the members. [46] Now, following this exhausting service, the time came for the two apostles to return home. On 17 August they, together with forty men, eight wagons, two or three women, and about one hundred animals, departed for the Rocky Mountains, taking with them another $1,007 in tithing, which they had collected between 4 July and 15 July, mostly from Saints on the San Francisco Peninsula. In the Carson Valley, Elder Rich received a letter instructing him to remain in California a little longer to complete some Church business. Elder Lyman and his group continued east, while Elder Rich retraced his steps across the mountains.

As Elder Lyman’s party crossed the desert, they witnessed a ghoulish scene not to be forgotten. Thousands of rotting animal carcasses, innocent victims of gold-lust, were strewn along the trail. “The dead animals were so numerous that the stench was almost unbearable. One of our men, while he was riding along, counted 1,400 dead by the roadside, and there were hundreds more scattered over the plain.” [47]

Two of the brethren in the company died of cholera, but the rest arrived safely in the Salt Lake Valley on 29 September.

Those returning were “good advertisements for the folly of ‘chasing after gold.’“ Brigham Young asked Albert Thurber if he was “disappointed in returning home with so little.” Without hesitation Thurber answered, “I never felt better [than] when I got over the mountain.” [48] Elder Lyman’s account was equally dour. He said that the gold fields were “swamped in blood” and that the area was “depopulated by ravages of cholera.” Indeed, there was a particularly virulent outbreak of cholera that fall, undoubtedly due to streams polluted by the hordes of humanity and the dead animals. Nevertheless, Elder Lyman added, “Gold is not the god of the Saints. Rather, they ‘seek to build up the Kingdom of God by industry, by building cities.’“ [49]

Though the Church decried the lust for wealth, there can be no denying that California gold was a gift of divine providence that brought economic viability to the otherwise isolated outposts in the Great Basin. It also relieved suffering elsewhere. That fall alone, when members were asked to donate money to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, some six thousand dollars were raised, “mostly from California returnees.” [50]

Back in California, Elder Rich visited as many of the Latter-day Saints as he could, encouraging them in their faith. During the next month and a half he collected from them well over one thousand dollars in tithing. [51] Concerned about the faith of the young gold miners, Elder Rich described to President Young a strategy he had devised to “send some Elders to the Sandwich [Hawaiian] Islands, and as many other places as I can as I think they will be better of[f] away from hear when the rainy season commences as there can be but little done at mining in this country during the rainy season. All flock to the Towns and citys and the chief employ is gambling and drinking which has already allmost if not quite destroyed many of the brethren.” [52]

On 24 September, Elder Rich met with some of the Latterday Saint miners in their tent at Slap Jack Bar. “We were glad to see him/’ Henry W. Bigler wrote in his diary, “for he seems to us like a father among his sons advising and telling us what to do for the best.” [53] The next day Elder Rich conducted a special meeting among the miners, in which he disclosed his plan to call them on missions. Boyd Stewart was assigned to Oregon and nine others to the Hawaiian Islands: Thomas Whittle, Thomas Morris, John Dixon, George Q. Cannon (who, in addition to his mining mission, was keeping a store for the Great Salt Lake Trading Company), William Farrer, John W. Berry, James Keeler, James Hawkins, and Henry W. Bigler. These were the first Latter-day Saint missionaries sent to Hawaii. Bigler regarded his call as inspired. Just before coming with Elder Rich to California as a gold missionary, Bigler had recorded in his diary: “Last night I dreamed I was not going for goal [gold] but was going to the islands to preach the Gospel.” [54]

By 5 October, Elder Rich had completed his work and left for home. One of those who accompanied him was Porter Rockwell, who left California in a hurry under unusual circumstances. When Boyd Stewart, a former member of the Battalion, challenged Rockwell to a shooting match, hundreds of miners gathered at “Brown’s” Halfway House to witness the contest. Rockwell won easily. Because “Brown” was one of the most popular men in town, his winning provided an occasion to celebrate. Bitter in his defeat, Stewart wanted to get even, so he yelled out “Brown’s” true identity. Many in the drunken mob were old Mormon-haters from Missouri and Illinois who bore personal grudges against Rockwell. As they surged forward to lynch him, he mounted his horse and got out of town just in time, leaving his profitable California businesses behind forever. [55] The Rich-Rockwell party arrived safely in the Salt Lake Valley on 11 November.

The newly called Hawaiian missionaries left the mines in mid-October, and at Mormon Island they picked up their president, Hiram Clark. On 10 November they met at the home of Brannan’s former counselor, Ward Pell, who lived a short distance from San Francisco, and rebaptized him in the Bay. [56] The elders finally sailed for the Islands, despite stormy weather, on 22 November. [57]

California Becomes a State

As gold fever had waned in late 1849, residents began longing for a more stable situation. Miners’ law was adequate in the gold camps, where justice was swift and certain and served to prevent total anarchy. However, in the more settled areas, people were interested in a more sophisticated arrangement, including California statehood. To this end, groups began meeting in 1849 to initiate the process. Judge Peter Burnett, Joseph Smith’s legal counsel at the time he and other Latter-day Saint leaders were in Missouri’s Liberty Jail, was elected president of a group meeting in Sacramento. [58] Brannan and John Fowler were among the five men selected to officially write up the resolutions passed in this meeting. An election on 1 August was held to choose delegates for a constitutional convention. None of those chosen were Latter-day Saints. If the Saints had known how important this formative convention was to their leaders in Utah, they undoubtedly would have been more active in its proceedings.

Simultaneously, the inhabitants of the Great Basin petitioned for their own statehood. However, their petition had a flaw: there was insufficient population for their proposed state of “Deseret.” Newly elected U.S. president Zachary Taylor, whom the Saints had supported, now sought their cooperation. Taylor wanted California in the Union but was afraid Congress would impede the effort in a protracted debate over slavery. For several years, there had been an effort in the Senate to maintain a balance between slave states and free states, but the recent admission of Texas as a slave state upset that balance.

To assure that California would be admitted as a free state, the president wanted to counterbalance the many southern transplants in California with the anti-slavery Latter-day Saints in Utah. Therefore, he proposed combining the two areas into one state to be called California, with present-day Utah being “Eastern California” and the coastal region “Western California.” Since Utah’s population was too small for Utah to be granted statehood independently, joining with California would allow the Saints immediate statehood.

General John Wilson, on his way to California to serve as U.S. Indian Agent, stopped in Salt Lake City in August 1849 and shared President Taylor’s plan with Church leaders. Brigham Young approved President Taylor’s plan with the stipulation that there be an irrevocable provision whereby “Deseret” would automatically become a separate state in 1851 without further action of Congress. [59] On 6 September, the First Presidency wrote to Amasa Lyman in California, appointing him to work with General Wilson to implement the Saints’ plan. The letter to Elder Lyman maintained that regardless of the outcome, “we expect to inhabit that country [California] as well as this [Deseret].” [60] Unfortunately, however, Sierra Nevada snows prevented General Wilson from arriving in California with the petition until it was too late to be considered.

Meanwhile, in the fall of 1849, a constitutional convention met at San Jose to consider the matter of California statehood. During the convention, the issue of the new state’s eastern boundary was “fraught with the greatest diversity of opinion, fervor, and confusion.” [61] While some favored including all the former Mexican territory in the proposed state, others raised questions about the “excessive cost” and even “impossibility of governing so vast a region,” and the “undesirability, for some, of embracing the ‘peculiar’ Mormon community.” [62]

When the convention adjourned on 13 October, essentially the present-day eastern boundary, near the Sierra Nevada mountains, was adopted. On 13 November the voters ratified the constitution and elected Peter Burnett as governor, together with a provisional legislature. A certified copy of the constitution was sent to Washington with Capt. A. J. Smith, former commander of the Mormon Battalion. [63]

In January 1850, when General Wilson finally arrived in California, he and Elder Lyman presented their “memorial” to Governor Burnett, who “reviewed the several proposals one by one in a message to the legislature [at San Jose], condemning them all.” The pages of his voluminous recommendations outnumbered those of the petition itself. The governor believed that the coastal settlements and the Latter-day Saints in the Great Basin “were too far apart to be united even temporarily, and that Texas and Maine might as well be made one state as Deseret and California.’“ The assembly dismissed Elder Lyman’s proposal without an opposing vote. [64] Had the Saints been more attentive to civic matters and succeeded in getting elected to the legislature, they may have obtained statehood for Deseret from the process. Consequently, Latter-day Saints in the Rocky Mountains would have to wait almost fifty years for that to occur.

President Taylor’s fears about Congress were well founded, as debate regarding California’s statehood and slavery droned on through the spring and summer of 1850. Finally, the historic “Compromise of 1850” provided for the admission of California as a free state and for the creation of the territory of “Utah” (rather than “Deseret”). On 9 September, California was officially admitted to the Union—the only area to gain statehood without going through a probationary period as a territory. The news reached San Francisco when the USS Oregon arrived on 18 October. It had taken this steamship just over a month to travel from the East Coast to San Francisco, a voyage that just four years earlier had taken the wind-driven Brooklyn six months. Celebrations immediately erupted in San Francisco and surrounding areas.

As 1850 ended, the sun had set on the gold rush. Church leaders who had strengthened the faith of the California Saints had returned home. But there were plans on the table in Utah for new Latter-day Saint thrusts into what was now “The Golden State.”

Notes

[1] Quoted in Irving Stone, Men to Match My Mountains: The Opening of the Far West, 1840–1900 (New York: Berkeley Books, 1982), 137.

[2] Quoted in J. S. Holliday, The World Rushed In: The California Cold Rush Experience (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), 397.

[3] Ibid.

[4] John M. Horner, “Looking Back,” Improvement Era 8, no. 1 (November 1904): 32–33.

[5] Horner, “Adventures of a Pioneer,” Improvement Era 7, no. 7 (May 1904): 513.

[6] Ibid., no. 10 (August 1904): 770; Muir, 1:38.

[7] Horner, “Voyage of the Ship ‘Brooklyn,’” Improvement Era 9, no. 11 (September 1906): 890.

[8] Frank Soule, John H. Gihon, and James Nisbet, The Annals of San Francisco (New York: D. Appleton, 1855), 283–84, 715.

[9] Franklin A. Buck, quoted in Holliday, 365.

[10] Quoted in John Henry Evans, Charles Coulson Rich: Pioneer Builder of the West (New York: Macmillan, 1936), 196.

[11] Quoted in J. Kenneth Davies, Mormon Gold: The Story of California’s Mormon Argonauts (Olympus, 1984), 160–61.

[12] The Journals of Addison Pratt, ed. S. George Ellsworth (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1990), 427.

[13] Ibid., 432.

[14] Ibid., 431–32.

[15] Albert R. Lyman, Amasa Mason Lyman: Trailblazer and Pioneer from the Atlantic to the Pacific (Delta, Utah: Melvin A. Lyman, 1957), 202.

[16] Charles C. Rich Diary, 10 and 18 April 1850; LDS Church Archives.

[17] Journals of Addison Pratt, 432–33.

[18] Edwin G. Gudde, Sutter’s Own Story (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1936), 202; see also Richard Lloyd Dewey, Porter Rockwell: A Biography (New York: Paramount Books, 1987), 152–53; and Harold Schindler, Orrin Porter Rockxuell: Man of God, Son of Thunder (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983), 186–87.

[19] Quoted in Davies, 222.

[20] Ibid., 222–23.

[21] Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 162–63.

[22] Davies, 239.

[23] Abner Blackburn, Frontiersman: Abner Blackburn’s Narrative, ed. Will Bagley (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1992), 173.

[24] Davies, 239–42.

[25] Ibid., 241.

[26] Ibid., 244–45.

[27] Louisa Barnes Pratt, Mormondom’s First Woman Missionary: Life Story and Travels Told in Her Own Words, ed. Kate B. Carter (Utah: Nettie Hunt Rencher, 1950), 255.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Caroline Barnes Crosby Diary, July 1850; LDS Church Archives.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Quoted in Davies, 248.

[32] Crosby Diary, July 1850.

[33] Quoted in Larry C. Porter, “A Study of the Origins of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the States of New York and Pennsylvania, 1816–1831” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1971), 363.

[34] James R. Clark, comp., Messages of the First Presidency (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965), 2:46.

[35] Journal History, 23 April 1850 (hereafter JH); LDS Church Archives.

[36] Quoted in Davies, 249.

[37] Ibid., 320.

[38] Louisa Barnes Pratt, 256.

[39] Crosby Diary, 19 July 1850.

[40] Ibid., 21 July 1850.

[41] Louisa Barnes Pratt, 257.

[42] Ibid., 259.

[43] Quoted in Davies, 255.

[44] Henry W. Bigler, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962), 131.

[45] Charles C. Rich, quoted in Leonard J. Arrington, Charles C. Rich: Mormon General and Western Frontiersman (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 153–54.

[46] Ibid., 153.

[47] Lyman, 203.

[48] Quoted in Leonard J. Arlington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958), 76.

[49] Quoted in Davies, 264.

[50] Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, 77.

[51] Davies, 265–67.

[52] Quoted in Arrington, Rich, 154.

[53] Andrew Jenson, comp., “The California Mission,” 24 January 1848 (hereafter CM); LDS Church Archives.

[54] Henry W. Bigler, Book B, quoted in Campbell, 153.

[55] Dewey, 157; Schindler, 190.

[56] CM, 10 November 1850.

[57] Ibid., September–November 1850.

[58] Hubert H. Bancroft, History of California (San Francisco: The History Co., 1888), 6:644.

[59] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 3:437–39.

[60] JH, 6 September 1849.

[61] Neal Harlow, California Conquered: War and Peace on the Pacific, 1846–1850 (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982), 345.

[62] Ibid., 346.

[63] Ibid., 351.

[64] Roberts, 3:440.