The Epic March of the Mormon Battalion: 1846–47

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 59–80.

The story of the Mormon Battalion began with the desperate need the Saints had, both individually and collectively, for cash. Having been driven from Nauvoo in the cold winter, many were sick and destitute. During the spring and summer of 1846, they scattered throughout Iowa, many working as day laborers to scrape enough money together to outfit themselves for the trek west.

To assist the Pioneers with their monetary needs, Church leaders in Nauvoo publicly announced in a circular their desire to obtain a government contract to build a chain of stockade forts along the Oregon Trail. [1] But given the prevailing anti-Mormon attitude and the tense situation with Mexico, government leaders would not sanction any plan that would give the Saints so much military influence in the West.

Behind-the-Scenes Negotiations

On 26 February, Brigham Young wrote to Jesse C. Little, a thirty-year-old New Englander, appointing him to preside over the Eastern States Mission. President Young continued to encourage California settlement, instructing Little: “If our government shall offer any facilities for emigrating to the western coast, embrace those facilities if possible.” [2]

In Philadelphia, Little was introduced to Col. Thomas L. Kane, who understood the Saints’ dilemma, and the two became fast friends. Kane wrote a letter to the vice president of the United States urging the government to aid the Saints, who, he testified, “still retain American hearts, and would not willingly sell themselves to the foreigner.” [3]

Little arrived in Washington, D.C., on 21 May 1846, one week after the United States declared war on Mexico. Two days later, with the assistance of A. G. Benson, Little was able to secure an appointment with Amos Kendall, the former postmaster general who had sought to extort Brannan and who still wielded considerable influence in the U.S. capital. Kendall “thought arrangements could be made to assist our emigration by enlisting one thousand of our men, arming, equipping, and establishing them in California to defend the country.” [4]

On 27 May, Kendall informed Little that he had broached the subject with President James K. Polk, who by this time “had determined to take possession of California,” and was considering, with his cabinet, the possibility of using Latter-day Saint volunteers to “push through and fortify the country.” [5] The president and his cabinet had already dispatched Col. Stephen W. Kearny, then stationed at Fort Leavenworth, to travel via Santa Fe to California.

By 1 June, Little had not received any definite word on the proposed use of Latter-day Saint troops, so he wrote a lengthy letter to the president in which he requested “some pecuniary assistance” for the westward migration of his persecuted people. “We would disdain to receive assistance from a foreign power,” Little wrote, “unless our government should turn us off in this grant” and thus “compel us to be foreigners.” [6]

President Polk’s diary entry for the following day records that Colonel Kearny was specifically “authorized to receive into service as volunteers a few hundred of the Mormons who are now on their way to California. . . . The main object of taking them into service would be to conciliate them, and prevent them from assuming a hostile attitude towards the U.S. after their arrival in California.” [7] On 3 June, Jesse Little had a three-hour interview with the president, who stated that he had received Little’s letter and wished to help him but had not worked out all the details.

That same day, however, President Polk and the secretary of war finalized the orders to Colonel Kearny: “It is known that a large body of Mormon emigrants are en route to California, for the purpose of settling in that country. You are desired to use all proper means to have a good understanding with them, to the end that the United States may have their co-operation in taking possession of and holding, that country. . . . You are hereby authorized to muster into service such as can be induced to volunteer; not, however, to a number exceeding one-third of your entire force.” He indicated that the Saints would be paid like other volunteers and be able to nominate some of their own men to serve as officers. [8] On 5 June, President Polk, in another interview, informed Little of this decision. [9] Recruiting the Battalion On 19 June, just a week before he left Fort Leavenworth for Santa Fe with his first contingent of troops, Kearny complied and dispatched Capt. James Allen to the Latter-day Saint camps in Iowa to raise five hundred volunteers. Accompanied by three dragoons (armed cavalry), Captain Allen arrived at Mount Pisgah just one week later. There was some grumbling among the Saints about being asked to serve a country that had allowed them to be expelled; some even believed that this was a plot to destroy them. Nevertheless, Brigham Young immediately endorsed the proposal and went with Allen throughout the scattered camps, chastening the naysayers and soliciting volunteers. On 7 July, President Young “addressed the brethren on the subject of raising a Battalion to march to California.” Jesse C. Little, who had just arrived the day before from the East, spoke to the same gathering. As a result, sixty-six men volunteered. [10] Captain Allen explained that forming a Mormon battalion “gives an opportunity of sending a portion of their young and intelligent men to the ultimate destination of their whole people, and entirely at the expense of the United States, and this advanced party can thus pave the way and look out the land for their brethren to come after them.” [11]

Furthermore, as Brigham Young concluded, “the Mormon Battalion was organized from our camp to allay the prejudices of the people, prove our loyalty to the government of the United States, and for the present and temporal salvation of Israel.” Battalion members would be able to send money to their families in Iowa, which would help finance their westward migration. [12]

In less than a month, the quota was filled. The volunteers enlisted into service on 16 July 1846 for a period of twelve months. Brigham Young instructed them that after being disbanded they could work on the coast if they wished, but holding to his original plan for the Saints’ settlement, he emphatically reminded them that the next temple would not be built there, but in the Rocky Mountains, “where the brethren will have to come to get their endowments.” He further explained that the Saints were going to the Great Basin, where they would be safe from mobs and that the Battalion would “probably be dismissed about 800 miles from us.” [13]

No one could have known just how difficult the twelve months of Battalion service would be. Throughout the march, conditions were generally bad. Nevertheless, President Young promised the recruits that none would be killed in battle “if they will perform their duties faithfully without murmuring and go in the name of the Lord, be humble and pray every morning and evening.” [14]

The approximately five hundred volunteers were joined by thirty-five women—some of them serving as army laundresses— and many children. The Latter-day Saint soldiers buttressed Kearny’s “Army of the West.”

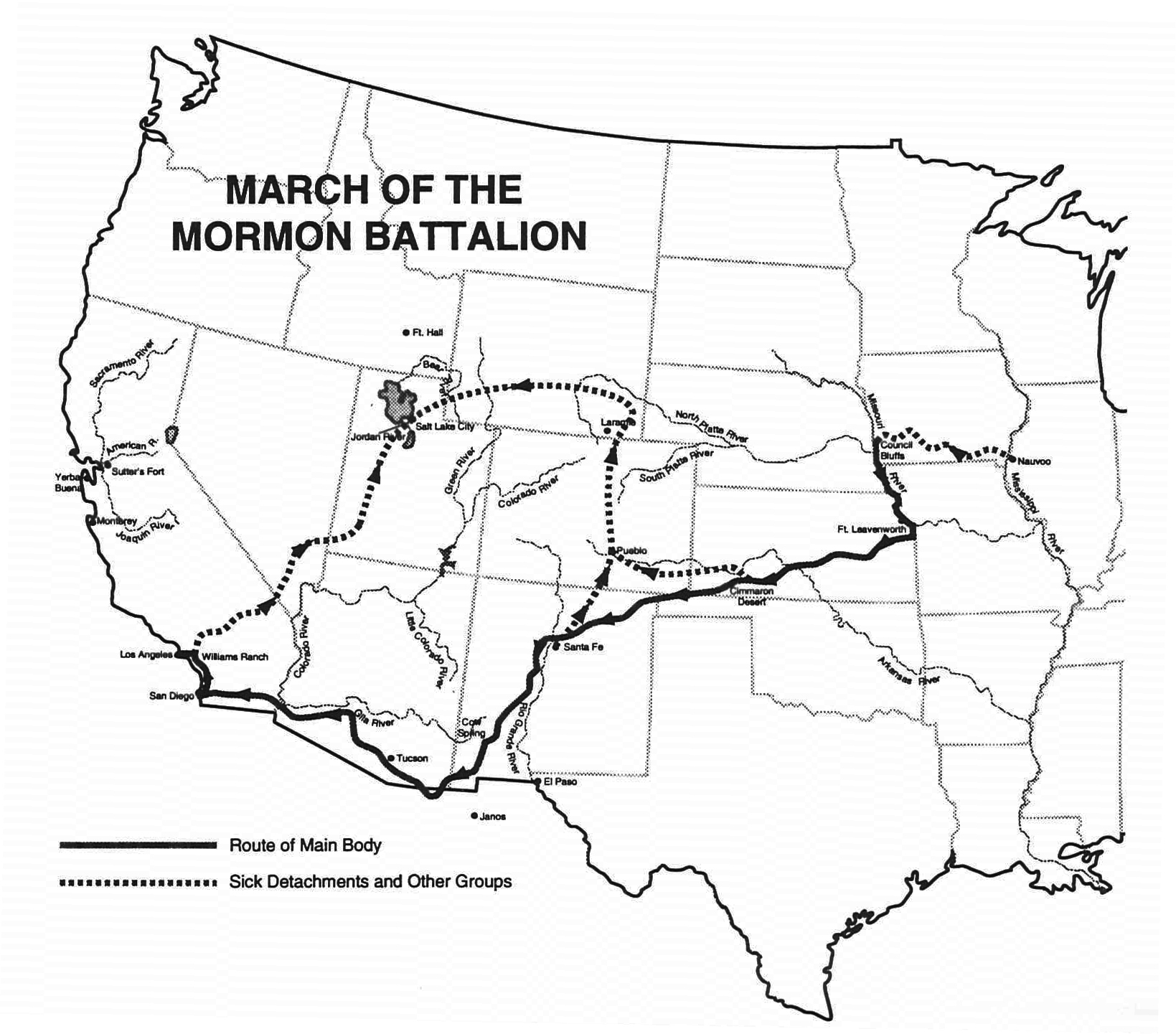

The Battalion marched from Council Bluffs on 21 July and recorded its first fatality the following day, when Samuel Boley became ill and died. They endured unbearably hot weather, torrential rain, and even a tornado. Many became sick from exposure and lack of provisions before they marched the two hundred miles to Fort Leavenworth for supplies.

On 29 July they marched through St. Joseph, Missouri, and found the townspeople astounded that the Latter-day Saints had volunteered to serve a United States government that had turned a deaf ear to their cries for redress. On 1 August, the day after the Brooklyn dropped anchor in San Francisco Bay, the Battalion reached Fort Leavenworth and was amply outfitted— a mixed blessing since each soldier would have to carry a heavy pack. A Missourian, George B. Sanderson, became Battalion doctor; the Saints viewed this as a most unfortunate appointment. Each man received his allotted forty-two dollars clothing allowance for the year, but instead of purchasing new uniforms, many sent the money back to aid their families and the general emigration effort. The paymaster noticed that the Battalion men, unlike many illiterate soldiers, could sign their names. In fact, the several detailed diaries kept made it one of history’s best-documented military marches. They also conducted religious services throughout their march—an unusual practice for soldiers.

Along the Santa Fe Trail

The Battalion followed the old Santa Fe Trail through what is now Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico into Santa Fe. The trail “was no mere line of ruts connecting two towns, two cultures. It was a perilous cruise across a boundless sea of grass, over forbidding mountains, among wild beasts and wilder men, ending in an exotic city offering quick riches, friendly foreign women and a moral holiday.” Travelers “knew only darkness, fatigue, cold and sunburn, the insistent wind, the drenching downpour, the lone danger of guard duty while the wolves howled from the hills and the skulking Comanche fitted an arrow to his bowstring.” [15]

Upon leaving Fort Leavenworth on 13 August, the Battalion’s original leader, James Allen, who was popular with the men, became ill, remained behind, and died ten days later. The agreement with the Battalion was that if for any reason they lost their commander, they were to choose one of their own to take his place. They chose Capt. Jefferson Hunt.

Less than a week after they left Fort Leavenworth, a powerful storm hit them. “About sun down,” wrote Henry Standage, “the wind commenced blowing very hard accompanied with large drops of rain and continued to blow till our tents were all blown down and our cooking utensils scattered all over the Prairie.” [16] Robert Bliss, a fellow soldier, described the storm this way: “We had hardly time to pitch our tents before the storm came down upon us, it tore our tents from their fastenings, overturned our light wagons and prostrated men to the ground. The vivid lightning and the roar of the thunder and hail caused horses and mules to break from their fastenings and flee in every direction on the wide prairie.... Lieutenant Ludington’s carriage was overturned with his wife and Mother in it and our Orderly’s Carriage was sent before the storm 15 or 20 rods and he in pursuit of his wife in it.” [17]

On 29 August, two weeks after the Battalion departed Fort Leavenworth, Lt. Andrew Jackson Smith of the regular army intercepted the Battalion and took command from Captain Hunt, a move which violated the agreement between the U.S. Army and the Church. Lieutenant Smith, a West Point graduate, disliked Mormons, and the Saints viewed his appointment as another unfortunate choice. The volunteers concluded that there was an unholy alliance between Smith and his accomplice, George B. Sanderson, the Battalion doctor. Smith, who looked on the LDS volunteers and their accompanying women and children as unfit for army service, confronted them with long, forced marches, making them sick. Then Dr. Sanderson concocted medicines of calomel and arsenic which, the men believed, either cured or killed. Brigham Young counseled the recruits by letter to turn to faith and priesthood ordinances for healing, and “let surgeon’s medicine alone.” [18]

Marching just a few days ahead of them was a large group of Missouri volunteers, some of whom were members of mobs that drove the Saints from Missouri eight years before. The two groups were sufficiently separated that, with the exception of brief confrontations at the crossing of the Arkansas River and at Santa Fe, they had no trouble with each other. The Indians, who fought against the incursions of the Whites both the year before and the year after, were strangely quiet that year. They ambushed, killed, and took the scalps of a few Missourians, but the Battalion was never bothered.

Through this part of the trek, the biggest problems were forced marches and dust. Pvt. Azariah Smith, who had just celebrated his eighteenth birthday during the march, recorded the following in his diary: “Tuesday Sept 1st. 1846. . . . I and Thomas went ahead this morning as my eyes were so sore that I could not travail in the dust of the Battalion. We travailed 15 miles and camped by a Spring on the prairy, called the Lost Spring. We arived at the Spring about 2 oclock, dry and dusty. . . . Monday Sept 14th. . . . The time goes very well with me except my eyes being very Sore.” [19]

On 10 September, the Battalion met a group of messengers en route to Fort Leavenworth with the report that on 18 August Kearny, who had been promoted to general, had taken Santa Fe without firing a shot. He wanted the volunteers to go directly to Santa Fe rather than taking the longer route via Bent’s Fort in Colorado. Lieutenant Smith followed orders and took the more direct but more difficult route through the Cimarron Desert.

On 16 September, Smith ordered a group of fifteen sick families, who he believed could not make the difficult march, to leave the main body and proceed instead to Pueblo, Colorado. There they joined fourteen families of Saints from Mississippi who had set up a semi-permanent camp while awaiting the main body coming overland with Brigham Young.

In the desert there were long stretches without water, except for occasional pools polluted with the urine and dung of animals. An increasing number of men and animals became sick. During the next three weeks there were only two days during which they had fresh water.

On 2 October the Battalion received word that General Kearny would discharge them unless they reached Santa Fe by 10 October. Consequently, the officers decided to split the command into two detachments: the able and the feeble. The able-bodied were force-marched to Santa Fe, arriving on 9 October. The feeble entered the town three days later. When the first group arrived they learned that Kearny had already pushed on toward California and had left Alexander W. Doniphan in charge at Santa Fe. General Doniphan had come to the defense of the Latter-day Saints at a crucial time during the Missouri persecutions eight years before. Now, as the Battalion marched into Santa Fe’s central plaza, he ordered his men to give them a one-hundred-gun salute from the rooftops of surrounding adobe buildings.

A New Wagon Road to the Coast

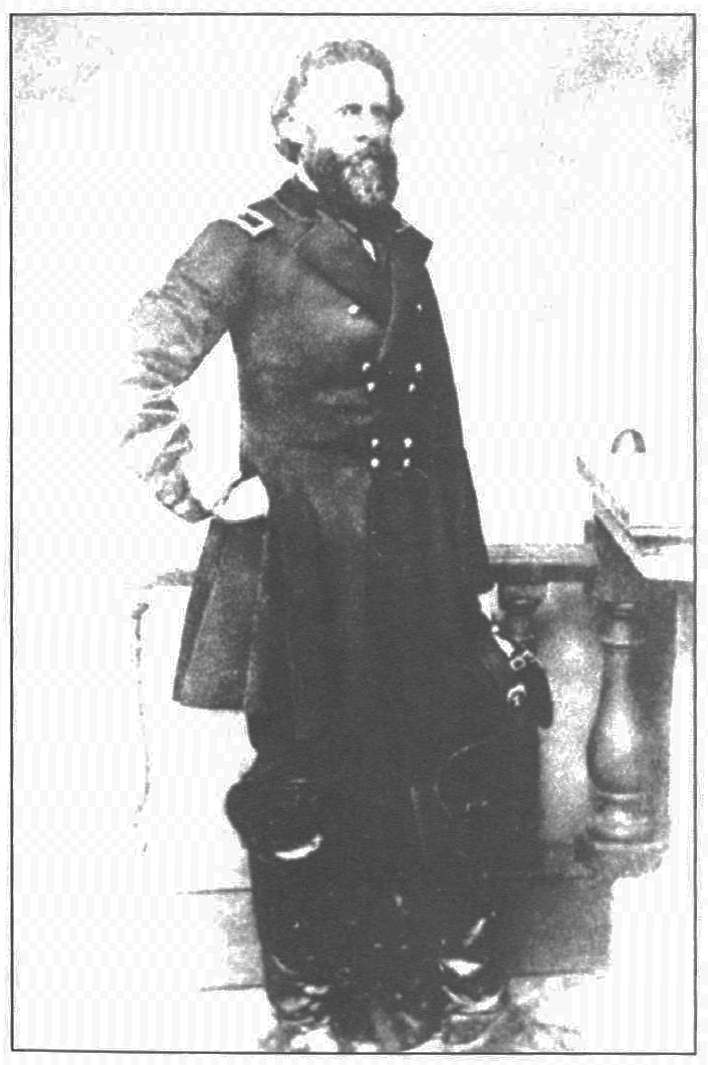

When General Kearny learned of Colonel Allen’s death, he appointed Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke, another West Point graduate, to take command of the Mormon Battalion at Santa Fe. Having anticipated the glories to be earned on the battlefield, Cooke was likely disappointed with this assignment to shepherd a group of inexperienced volunteers. His initial impression of the Battalion was quite discouraging: “It was enlisted too much by families; some were too old,—some feeble, and some too young; it was embarrassed by many women; it was undisciplined; it was much worn by travelling on foot, and marching from Nauvoo, Illinois; their clothing was very scant;—there was no money to pay them,—or clothing to issue; their mules were utterly broken down; the Quartermaster department was without funds, and its credit bad; and mules were scarce.” [20] These were hardly the criteria for an efficient battle-force. Nevertheless, as a recent historian has pointed out, the Battalion had “hidden yet great potential.” [21]

Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke

Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke

The preferred route from Santa Fe to the Pacific Coast was the Old Spanish Trail—through what is now central Utah to Southern California. There were trails on the more direct route from New Mexico through the Gila Valley of Arizona, but wagons had not been taken over them. Kearny, who left Santa Fe on 25 September intending to take wagons with him over the Gila route, soon abandoned them to make better time. He appointed Colonel Cooke and the Battalion to open the wagon road.

After the harsh conditions caused a second “sick detachment” to be dispatched to Pueblo, the Battalion left Santa Fe on 19 October with 397 men and twenty-five wagons, each wagon pulled by eight mules. Though their march would last another ninety days, the quartermaster was able to give the men only enough flour, sugar, coffee, and salt for sixty days, along with rations of salt pork for thirty days and soap for twenty.

The original plan was for the Battalion to follow Kearny’s route as closely as possible. Two weeks later, however, Cooke received word from Kearny advising him that wagons could not cross the mountains on the most direct route to the Gila and consequently directed him to go farther south along the Rio Grande before turning west. This more southerly route was completely unexplored, and it was here that the Battalion made a significant and far-reaching contribution.

The rations were never increased but were often decreased. Though the Battalion passed through numerous Mexican villages, the curious natives were generally too suspicious or poor to part with food, except for a few apples and grapes. The terrain consisted of such deep sand, in so many places, that the animals could not pull wagons through without assistance. Battalion members, already burdened with heavy packs, had to use ropes to assist the animals in pulling the wagons much of the way. “Today the Captain had us divided off ten to a wagon, to push them up hills and over bad places,” Azariah Smith recorded. “We have only half rations now of flour and live cheafly on beaf which is very poor and tough.” [22]

On 10 November, about 250 miles from Santa Fe, fifty-five men became too weak to travel further and were sent back to Pueblo to join the other invalids. Now numbering about 360, including women and children, the Battalion continued down into the Rio Grande Valley. Along the way they saw intricate irrigation systems, some several miles long. Their observations were fortuitous, as the knowledge of irrigation later became a necessary survival skill both in California and in Utah.

On 13 November the volunteers left the banks of the Rio Grande and headed southwest to get around the end of the mountains. A strong north wind brought very frigid temperatures. “It was exceedingly cold last night,” Colonel Cooke recorded in his diary, “water froze in my hair this morning whilst washing.” [23]

About a week after leaving the Rio Grande, the Battalion’s scouts reported that they could not find adequate sources of water or a suitable pass ahead. A few of the men, therefore, hoping to attract someone who could recommend a better route, scaled a nearby hill and built a signal fire. A group of helpful Mexicans told them that just over a hundred miles farther south was an established westward trail passing through some settlements in what is currently northern Mexico. Cooke decided to take this detour. This decision again antagonized the Battalion; they felt it was not consistent with their mission to go straight to the coast. Daniel Tyler recalled that “a gloom was cast over the entire command.” That evening, fifty-five-year-old David Pettigrew encouraged the men to pray that the Lord might change the colonel’s mind, that he “might not lead up into battle or directly through the enemies strong holds where in all probability they would give up battle.” [24]

Nevertheless, the next morning Cooke led the Battalion directly south toward the Mexican settlements. After going only two miles, however, the trail turned southeast, and Cooke became alarmed that he would get too far to the east and run into unforeseen problems. That would rob him of his chance to carve a trail to the West Coast. Cooke “arose in his saddle and ordered a halt. He then said with firmness: ‘This is not my course.’“ [25] He swore that he would be “damned if he was going all around the world to get to California.” [26] He then directed the bugler to “blow the right,” thus turning the troops due west. Witnessing this, David Pettigrew blissfully exclaimed, “God bless the Colonel!” Tyler recalled that the colonel “glanced around to discern whence the voice came, and then his grave, stern face for once softened and showed signs of satisfaction.” [27]

During this part of the journey, the men curried favor with their commander through an ingenious solution to the problem of dragging the wagons through deep sand. A double file of foot soldiers went ahead of the wagons, stomping down the sand in ruts so the wagon wheels had firmer ground to roll over. The double column was rotated every hour. This unconventional plan worked rather well and was therefore followed from this point on.

After passing over the Continental Divide, the Battalion, on 30 November, lowered their wagons over a two-hundredfoot precipice in Guadalupe Canyon and emerged into what is now southeastern Arizona.

While marching along the San Pedro River on 11 December, the Battalion engaged in its only fight—a battle with wild bulls. Herds gathered along the line of march. Some of the bolder animals attacked the soldiers and gored several mules to death. The men had been ordered to march with their weapons unloaded, but they now loaded them to defend themselves, and “the rattle of musketry was for once heard all along the line.” [28]

Colonel Cooke wrote in his diary: “The animals attacked in some instances without provocation, and tall grass in some places made the danger greater.” Tyler was standing next to Cpl. Lafayette Frost when they saw an “immense coal-black bull” about one hundred yards away charging toward them. Frost aimed his musket deliberately but did not fire until the beast was only six paces away. Colonel Cooke feared that “one man’s ‘ignorance with some stubbornness’ was about to receive a terrible retribution.” But when he saw the huge bull lifeless at their feet, “how changed must have been his feelings.” [29]

The bulls became even more ferocious when wounded. Dr. William Spencer shot one animal five times: twice through the lungs, twice through the heart, and once through the head, yet the culprit “would alternately rise and fall and rush upon the doctor” until it was shot a sixth time directly between the eyes. Reports of the number of wild bulls killed ran from twenty to sixty, and one writer put the figure at eighty-one. [30]

At this point in the journey, a decision had to be made. The Battalion could march through Tucson for needed rest and supplies and shorten their route by one hundred miles. But Tucson was a village of five hundred, garrisoned by two hundred Mexican troops with cannons. After a cursory consideration, Cooke decided to take the shortcut and capture Tucson.

Upon the Battalion’s arrival, the two armies engaged in conversing, posturing, gesturing, threatening, arresting of emissaries, and so forth. But there was no gunfire. Finally, on 16 December the Battalion marched into town and found that the Mexican soldiers had abandoned it. The natives were friendly and shared their food. The soldiers in turn were respectful, though Cooke confiscated two thousand bushels of grain left behind by the Mexican Army.

1969 statue of Mormon Battalion soldier, sculpted by Edward Fraughton

1969 statue of Mormon Battalion soldier, sculpted by Edward Fraughton

The next leg of the trek was especially trying. Water became extremely scarce. For several days the men and their animals trudged along with no water except for occasional small, muddy ponds. On 19 December the main body of soldiers did not camp until after dark, but to cope with their exhaustion, some “stopped without leave being worn out. The Brethren were passing by at all hours through the night,” Henry Standage recorded in his journal, “still hoping that the Command had found water, travelling two or three miles at a time and resting.” [31]

When someone complained about the bawling, thirstcrazed mules, Colonel Cooke curtly rejoined, “I don’t care a damn about the mules, the men are what 1 am thinking of.” [32] When some pools of freshly fallen rainwater were finally found, Battalion men not only quenched their own thirst but also helped their fellow soldiers. For example, Lieutenant Rosencrans went back along the line “on a mule loaded with Canteens of water relieving those of Co C. who had lain out.” [33] Out of these difficult circumstances emerged an increasing mutual respect between Colonel Cooke and his men.

The Battalion reached the Gila River near the Pima Indian villages on 21 December, completing their assignment to open a wagon road from the Rio Grande. The significance of this accomplishment cannot be overestimated: they pioneered a new route through previously unexplored deserts between the mountainous Apache strongholds on the north and the Mexican frontier settlements on the south. This route would become a key link in a proposal for a southern transcontinental railroad. This in turn would make the 1853 Gadsden Purchase necessary, bringing what is now southern Arizona and New Mexico into the United States.

Colonel Cooke thought it might be easier to float supplies down the Gila River than to carry them to the river’s confluence with the Colorado. A raft was built of two wagon boxes and loaded with foodstuffs. However, the river’s sandbars soon overcame the raft and the precious food, both of which were lost. At this same time, on New Year’s Day 1847, Battalion members received from a group of eastward-bound travelers their first word that the colony of Saints from New York had successfully landed and was preparing a base of operations at San Francisco Bay.

After crossing the Colorado into California on 10 January, things got worse. Although General Kearny had dug some wells for the trailing Battalion, many had become dry, so new ones had to be dug. Colonel Cooke described the days between 12 and 16 January as the hardest of all. Tyler concurred:

We here found the heaviest sand, hottest days and coldest nights, with no water and but little food. . . . At this time the men were nearly barefooted; some used, instead of shoes, rawhide wrapped around their feet, while others improvised a novel style of boots by stripping the skin from the leg of an ox. . . . Others wrapped cast-off clothing around their feet. [34]

As the Battalion left the desert and entered the Coast Range, they came to Box Canyon, which was too narrow for their wagons. Even though most of their tools had been lost with the makeshift raft on the Gila River, the men now had to chisel a passage through “a chasm of living rock.” Colonel Cooke set the example by wielding one of the axes. [35]

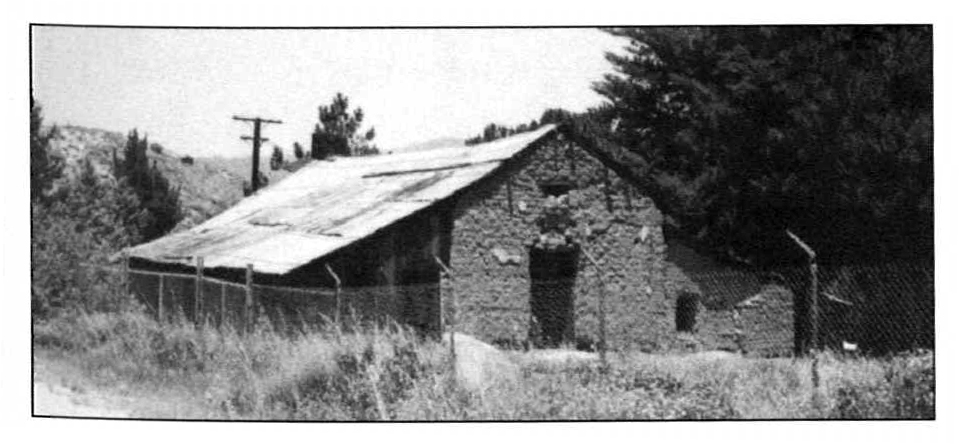

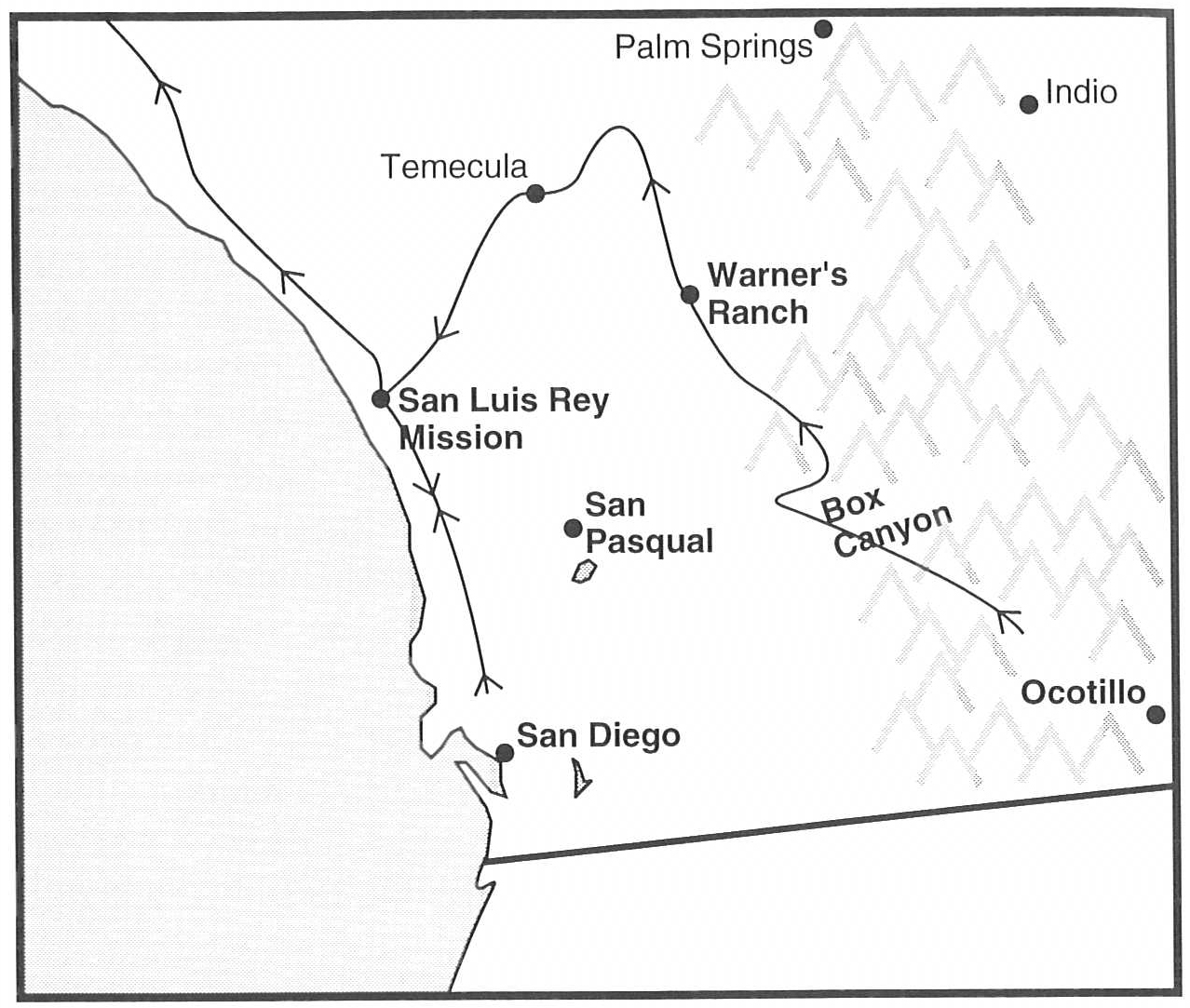

On 21 January, the Battalion reached Warner Ranch (now in the Cleveland National Forest, northeast of Escondido), Mormon Battalion route into the San Diego area where one Anglo man and three hundred Indians lived. Warner, upon hearing of their approach, hid all his foodstuffs, leaving the soldiers to dine on unsalted beef and a few pancakes made by the Indians. However, there were hot and cold springs—healing balm for aching feet, limbs, and joints.

Original Warner Ranch building

Original Warner Ranch building

Upon leaving the ranch, the soldiers passed without incident by San Pasqual, a small village where just over a month before, General Kearny’s soldiers had encountered a group of Mexican “Californio” defenders who had killed Capt. Benjamin D. Moore and seventeen of his men. The Mormon Battalion first headed toward Los Angeles then received orders to detour into San Diego instead. By this time, California’s landscape had taken on the luscious, emerald-green coat of January. As they marched through picturesque wooded hills and verdant winter valleys, they marveled at the fauna and flora, including vast seas of yellow-flowered mustard greens, which became new elements in their diet.

Mormon Battalion route in the San Diego area

Mormon Battalion route in the San Diego area

Sighting the Pacific

On 27 January 1847 the Mormon Battalion sighted the Pacific Ocean. Every soldier who kept a diary attempted to put his feelings into words. Typical is the entry of Daniel Tyler:

The joy, the cheer that filled our souls, none but worn-out pilgrims nearing a haven of rest can imagine. Prior to leaving Nauvoo, we had talked about and sung about “the great Pacific Sea,” and we were now upon its very borders, and its beauty far exceeded our most sanguine expectations. . . . The next thought was, where, oh where were our fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, wives and children. [36]

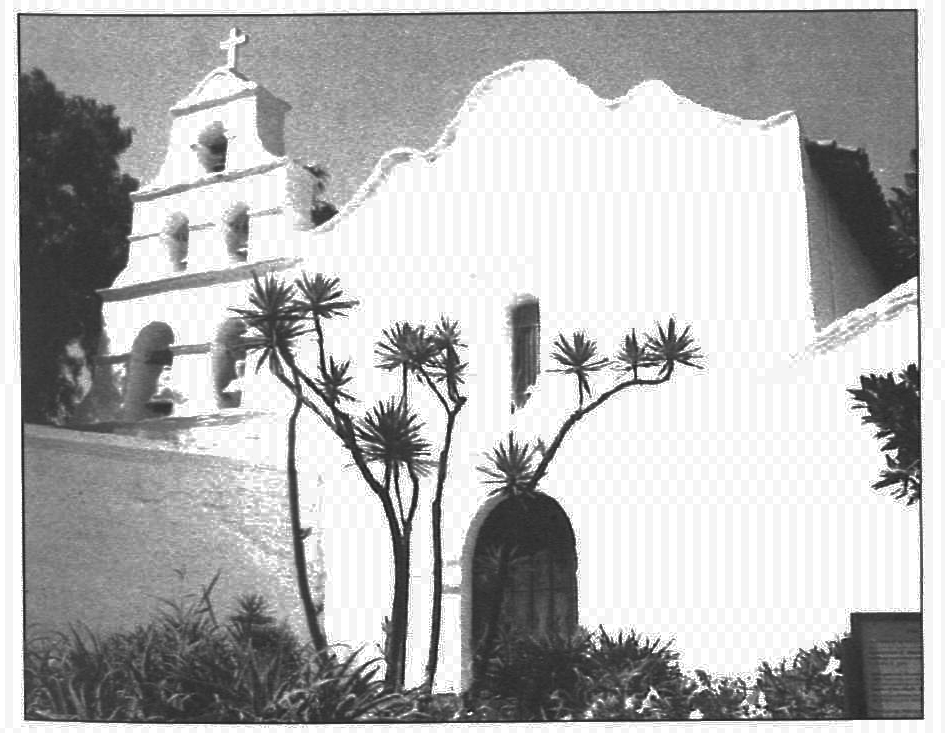

On 29 January, almost exactly six months after the Brooklyn landed at San Francisco, the march ended. The Latter-day Saint soldiers were quartered near the Catholic mission some five miles outside San Diego. Both the Battalion’s grueling land march and the Brooklyn’s arduous sea voyage had taken six months. Both groups had known danger, storms, sickness, shortness of provisions, and an equal number of deaths. And both were happy to be at their Pacific destination.

San Diego Mission

San Diego Mission

Despite Col. Philip St. George Cooke’s initial misgivings about taking over a ragtag group of worn-out volunteers, he became attached to the Battalion and inspired by their admirable courage and long-suffering over the epic 1,100-mile trek from Santa Fe to San Diego. The day after arriving, Cooke wrote the following commendation, which was subsequently read to the Battalion:

The Lieutenant-Colonel commanding congratulates the battalion on their safe arrival on the shore of the Pacific Ocean, and the conclusion of their march over two thousand miles.

History may be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry. Half of it has been through a wilderness where nothing but savages and wild beasts are found, or deserts where, for want of water, there is no living creature. There, with almost hopeless labor we have dug deep wells, which the future traveler will enjoy. Without a guide who had traversed them, we have ventured into trackless table-lands where water was not found for several marches. With crowbar and pick and axe in hand, we have worked our way over mountains, which seemed to defy aught but the wild goat, and hewed a passage through a chasm of living rock more narrow than our wagons. To bring these first wagons to the Pacific, we have preserved the strength of our mules by herding them over large tracts, which you have laboriously guarded without loss. The garrison of four presidios of Sonora concentrated within the walls of Tucson, gave us no pause. We drove them out, with their artillery, but our intercourse with the citizens was unmarked by a single act of injustice. Thus, marching half naked and half fed, and living upon wild animals, we have discovered and made a road of great value to our country.

Arrived at the first settlement of California, after a single day’s rest you cheerfully turned off from the route to this point of promised repose, to enter upon a campaign, and meet, as we supposed, the approach of an enemy; and this, too, without even salt to season your sole subsistence of fresh meat. . . . Thus, volunteers, you have exhibited some high and essential qualities of veterans. [37]

As one might expect, Cooke’s words were “cheered heartily by the Battalion.” [38]

Impressive monuments in California and Utah, as well as a staffed visitors center in San Diego, would in later years celebrate the Mormon Battalion’s accomplishments. But their service did not end with their epic march. They had much more to contribute to early California. Their community work and their key roles in one of the state’s most historic events—the discovery of gold—are also stories worth telling.

Notes

[1] History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1957), 7:570.

[2] Quoted in Journal History, 6 July 1846 (hereafter JH); LDS Church Archives.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] The Diary of James K. Polk, ed. Milo Milton Quaife (Chicago: A.C. McClurg, 1910), 1:444,446.

[8] U.S. Congress, Senate, 30th Cong., 1st sess., 1847–48, Senate Executive Document no. 60, as quoted in John F. Yurtinus, “A Ram in the Thicket: The Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War” (Ph.D. diss., Brigham Young University, 1976), 34–35.

[9] JH, 6 July 1846.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Circular to the Mormons” quoted in JH, 26 June 1846.

[12] JH, 14 August 1846.

[13] Willard Richards Diary, 14 July 1846 and 18 July 1846, as cited in Yurtinus, 53–54, 59.

[14] Elden J. Watson, Manuscript History of Brigham Young (Salt Lake City: E. J. Watson, 1971), 264.

[15] Stanley Vestal, The Old Santa Fe Trail (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1939), preface, viii.

[16] Frank A. Colder, The March of the Mormon Battalion: From Council Bluffs to California (New York: The Century Co., 1928), 148.

[17] Robert S. Bliss Diary, 19 August 1846; typescript, LDS Church Archives.

[18] Daniel Tyler, A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War (Glorieta, N. Mex.: Rio Grande Press, 1881), 146; see also Susan E. Black, “The Mormon Battalion: Conflict Between Religious and Military Authority,” Southern California Quarterly 74, no. 4 (winter 1992): 313–28.

[19] Azariah Smith, The Gold Discovery journal of Azariah Smith, ed. David L. Bigler (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press^ 1990), 23, 26.

[20] Philip St. George Cook, The Conquest of New Mexico and California in 1846–1848 (Chicago: Rio Grande, 1964), 91.

[21] Dwight L. Clarke, Stephen Watts Kearny: Soldier of the West (Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 166.

[22] Smith, 47.

[23] Philip St. George Cooke, William Henry Chase Whiting, Francois Xavier Aubry, Exploring Southwestern Trails 1846–1854, ed. Ralph P. Bieber (Clendale, Calif.: Arthur H. Clark, 1938), 105.

[24] Henry W. Bigler Diary, Book A, 48; typescript in possession of Larry C. Porter, Brigham Young University.

[25] Tyler, 207.

[26] Henry W. Bigler, Bigler’s Chronicle of the West, ed. Erwin G. Gudde (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962), 28.

[27] Tyler, 207.

[28] B. H. Roberts, The Mormon Hattalion: Its History and Achievements (Salt Lake City: The Deseret News, 1919), 38.

[29] Tyler, 220.

[30] Roberts, 38–39; Tyler, 219–20.

[31] Colder, 197.

[32] William Coray Diary, 19 December 1846, quoted in Yurtinus, 415.

[33] Colder, 197.

[34] Tyler, 244–45.

[35] Roberts, 47–48.

[36] Tyler, 252.

[37] Cooke, Conquest, 197.

[38] Tyler, 255.