The Depression Years: 1929–1939

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 283–300.

As in early Church history, national events in the twentieth century affected the Church’s ability to pursue its agenda. Few external forces had a greater impact on the course of modern Latter-day Saint history than did the Great Depression.

Nationally, the industrial and technological advances of the previous several decades had resulted in robust economic expansion, which in turn had engendered a spirit of unbridled optimism. This mood suddenly changed, however, with the stock market crash on “Black Tuesday,” 29 October 1929. Early in 1930, business declined sharply. As a result, many factories and retail outlets were forced to close, even as surpluses piled up in warehouses. As thirteen million individuals lost their jobs, the nation’s banks began to collapse under the strain. By 1932 some five thousand financial institutions were depleted of the hard-earned savings of millions of depositors and became insolvent. Many people quivered in the cold, standing in lines on city sidewalks to obtain a hot bowl of soup or piece of bread, while in agricultural areas farmers could not afford to plant new crops, and old harvests rotted in granaries or were burned as fuel.

The Great Depression hit California hard. Some half million people lost everything they had in 1930 alone. But operating on the mistaken premise that conditions had to be better in California, “thousands of hollow-eyed, wasted refugees guided their broken automobiles into the state, seeking jobs, seeking sunshine, seeking hope.” [1] As the full weight of the Depression settled on the state, California was fettered with a massive surplus of labor. Thus, those who forsook their homes to pursue their dreams in California were rudely awakened as they found conditions there to be much the same as in the places they had left behind. The term “Golden State” seemed a mockery.

Migration from Utah Continues

The Depression’s impact was even more severe in the Mountain West. In 1932 unemployment in Utah reached 35 percent, compared to a national peak of 24.9 percent. Average personal income in the Beehive State fell by 48.6 percent.

In this environment, many Intermountain Latter-day Saints took flight. California Church membership more than doubled again from 20,599 in 1930 to 44,784 in 1940. Church president Heber J. Grant continued to request that capable Utah businessmen relocate in order to provide leadership for the growing Church and the thousands of struggling Saints in California.

One of those businessmen was the charismatic LeGrand Richards, who at great personal sacrifice left his thriving real estate business in Salt Lake City and moved his family to Los Angeles. In the next five years he served as bishop of the Glendale Ward and then as president of the Hollywood Stake, a position he left in order to preside over the Southern States Mission. [2] He later authored his classic book, A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, and served as the Church’s Presiding Bishop and as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

LeGrand Richards

LeGrand Richards

Continued growth required the formation of more Church units. During the 1930s, the number of stakes in California nearly quadrupled from three to eleven. New stakes were formed out of the California Mission in Gridley, Sacramento, and San Bernardino, LeGrand Richards while division of existing stakes resulted in two stakes in San Francisco and six in Los Angeles. In areas like San Jose, Santa Barbara, Fresno, and Bakersfield, branches continued to grow. In dozens of smaller cities like Alturas, Brawley, Escondido, Eureka, Gilroy, Hanford, Hemet, Indio, Lancaster, Lompoc, Placerville, Porterville, Redding, Salinas, San Rafael, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, Ukiah, and Watsonville, new branches were organized. By the end of the decade, most cities and many towns had functioning wards or branches.

Church Response to Depression Problems

As economic conditions worsened, local Church leaders’ shoulders strained under increasing burdens. Especially in such urban areas as Los Angeles and San Francisco, the stakes had to provide assistance to the numerous families in distress, many of which were new arrivals. Furthermore, the doubling of membership not only taxed existing Church programs and services, but it also created a need for more meetinghouses in many areas—at just the time when they could be afforded least.

In 1932 Los Angeles County had four hundred thousand cases on its relief rolls, including hundreds of Latter-day Saint families. Newcomers were not eligible for public relief. In response to these dire circumstances, the Inter-stake Employment and Relief Office was opened that year in Los Angeles under the direction of Alice H. Osborn—four years before the inauguration of a Churchwide welfare program. The Church Employment Office established contacts with superintendents and personnel directors. The Office also became a clearing house for membership records, since many people seeking assistance made dubious claims to being members of the Church. During the years in which Mrs. Osborn directed this office, some thirty-six thousand people came for information, relief, or other services. She succeeded in providing five thousand jobs, more than one for every Latter-day Saint family. [3]

The Depression also brought an enhanced and expanded role for the LDS women’s Relief Society. These women were instrumental in administering relief for needy families. The ward bishop was in charge of relief funds and commodities donated by members. However, he entrusted to the Relief Society not only the investigation of family needs but also the dispensing of available funds and materials. “The product of Relief Society handicraft and the canned fruits and vegetables processed with women’s help in the canning plants, represented by far the major part of the substance provided for welfare distribution.” [4]

A hint that the General Authorities were considering a Churchwide effort came three years later in a 1935 Oakland Stake conference, where Elder Melvin J. Ballard of the Quorum of the Twelve declared, “Our economic problems will not be solved by a Stalin of Russia, a Hitler of Germany, a Mussolini of Italy, a Huey Long of Louisiana, nor a Sinclair of California. The Lord has a plan, and when men will follow it, our troubles will be over.” [5]

Upton Sinclair had run unsuccessfully for governor on the Democratic ticket the previous year. Though President Heber J. Grant was also a Democrat, he rejected Sinclair’s socialist ideals, which undermined the concepts of individual dignity and responsibility. President Grant’s views were widely noted in California’s newspapers.

The Church’s welfare plan was announced at the April 1936 general conference. The First Presidency later explained why the Church launched this effort: “Our primary purpose was to set up, in so far as it might be possible, a system under which the curse of idleness would be done away with, the evils of a dole abolished, and independence, industry, thrift and self respect be once more established amongst our people. The aim of the Church is to help the people to help themselves. Work is to be re-enthroned as the ruling principle of the lives of our Church membership.” [6]

The welfare plan provided both cash and commodities to those in need. Church leaders gave renewed emphasis to the Saints’ longstanding tradition of fasting two meals each month and donating the financial equivalent of those meals to the Church for the poor. These “fast offerings” were first used to help the needy within the local congregation, but any surplus was then shared with other wards and stakes. The Church purchased farms, opened canneries, and developed other kinds of projects to produce a wide variety of goods which were placed in a “bishops’ storehouse” for distribution to those in need. Church members donated many hours of service working on these projects in order to help the less fortunate.

To coordinate these projects, a new level of Church administration was inaugurated. Stakes throughout the Church were grouped into thirteen “regions.” In California, stakes in the south were grouped into the Los Angeles Region and those in the north into the Oakland Region. Each region, consisting of between four and sixteen stakes, was to have a storehouse where commodities produced by stakes, both local and regional, could be exchanged. [7]

Each stake was assigned a specific production responsibility. In the Los Angeles Stake, where a member, Jay Grant, owned a clothing factory, the assignment was shirts. The Gridley Stake picked peaches from local orchards and canned them at the homes of Church members. In 1937 this stake processed thirty-five thousand cans, representing thirty-five tons of peaches. The Pasadena Stake transformed the basement of the Baldwin Park Ward building into a cannery. Pear culls were purchased in truckloads and ripened and sorted on tables in a member’s yard in El Monte. “Apricots, tomatoes, and other produce were harvested in the fields of the San Fernando Valley either as shares or as donations from owners who could not obtain the necessary labor to harvest them.” [8]

Another part of the Church’s welfare plan began in Southern California. In March 1938 the Pasadena and Hollywood Stakes joined in setting up a small workshop and salvage operation at 705 Ivy Street, Glendale, under the direction of Willard J. Anderson and Orville Shupe. The operation followed a pattern set by Goodwill Industries which had been established previously by some Protestant churches in the area. Later that year, Church leaders launched a similar Churchwide program named Deseret Industries.

The following year, the Glendale operation became part of the Deseret Industries system and moved to a larger, twostory facility at 116 Llewellyn Street, furnished with new equipment for processing salvage, sewing clothing, repairing furniture, etc.

Trucks collected clothing, furniture, appliances, newspapers, magazines, and other items that members wished to donate. Unemployed or disabled individuals then earned income by sorting, cleaning, and repairing these materials, which were then sold inexpensively in Deseret Industries retail stores. Proceeds from these sales paid the employees’ wages and financed other operating expenses. Salaries were supplemented, if necessary, with commodities from bishops’ storehouses. The objective was that all members, regardless of their abilities, would maintain self-respect doing worthwhile work and prove to themselves and to the world that they could earn their own way.

Deseret Industries, together with the bishops’ storehouse system, provided almost every item needed to sustain life. Each Latter-day Saint family received a monthly visit from a representative of the local ward bishop and the ward Relief Society president. If a family needed help, the Relief Society president determined with the bishop and the family what those needs were. If it was cash to forestall eviction or a utility shut-off, fast offerings were used. If food, clothing, or household goods were needed, a commodities “shopping list,” redeemable at a bishops’ storehouse or Deseret Industries outlet, was given to the family.

In return, Church members contributed what labor they could to the Church until they were able to stand on their own. Eventually, the system was expanded to provide a full range of social services. Although it was fine-tuned over the years, the essentials of this program, outlined by the First Presidency in 1936, were kept intact. After that time, no faithful California Latter-day Saint willing to work to his or her ability went unfed, unclothed, or unhoused.

The system worked so well that the sometimes hostile press began printing more positive stories about the Church. Although the long-range trend had been toward a less distorted image of the Latter-day Saints, it was not until these years that media coverage crossed the line from a predominantly negative to a predominantly positive character. Four-fifths of all magazine articles about the Church had titles specifically referring to the Church’s welfare program.

Missionary Efforts during the Depression

The Great Depression took its toll on missionary service, as fewer families were able to afford sending their sons and daughters on missions. In the California Mission, the number of missionaries plummeted from 147 in 1929 to 46 in 1932. [9] California stakes responded by calling some members to serve locally as stake missionaries. Elder J. Golden Kimball, a member of the First Council of the Seventy, “reported that hundreds had been converted to the Church” as a result of stake missionary efforts in Los Angeles and other areas. [10]

The mission president’s job was as important and demanding as ever, but it was changing as larger numbers of members were organized into stakes and therefore removed from his jurisdiction. Though increasing numbers of new mission branches in smaller areas still required staffing and support, the mission president was becoming a more distant figure to members in urban stakes, most of whom no longer had close personal contact with him or his work.

Furthermore, during the 1930s, mission presidents’ terms of service were shortened. In contrast to the more than ten years served by Presidents Robinson and McMurrin, two to five years became the norm, giving California three mission presidents during the decade. The high caliber of men appointed to preside over the California Mission was an indication of the importance that Church leaders attached to missionary work in the Golden State: Alonzo A. Hinckley of Millard County, Utah, became an apostle upon his release; Nicholas G. Smith of Salt Lake City, former president of the South African Mission and Acting Patriarch to the Church, later became an Assistant to the Twelve; and W. Aird Macdonald Jr. had been the first president of the San Francisco and Oakland Stakes.

During these years, the Church continued teaching the gospel to California’s Spanish-speaking population. Some of these people traced their roots back to the era when California was part of New Spain, but the majority were among the multitudes who flocked to the Golden State during the 1920s and 1930s. Most came from Mexico and settled in the barrio of East Los Angeles, which acquired a Mexican population second only to that of Mexico City itself.

Missionary efforts among Spanish-speaking Californians had been launched in 1924 when Rey L. Pratt of the Mexican Mission handpicked two elders to work in the Los Angeles area under the supervision of the California Mission. As additional missionaries became available, Spanish-speaking missionary work was expanded into such areas as San Diego and San Bernardino. Even top Church leaders became involved. On 28 August 1927, Joseph Fielding Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve spoke to over a hundred Spanish-speaking Saints at a special conference. And in February 1928 Anthony W. Ivins of the First Presidency, who had been born in Mexico, was able to speak to an even larger group in their native language. [11]

A Spanish-speaking branch was organized on 8 February 1928 in San Diego, and a similar unit was formed in Los Angeles on 16 June of the following year. Juan M. Gonzales became president of the Los Angeles Branch and continued in this office until 1944. There were fifty members when this branch was organized, but in four years it swelled to 345. Even though these Mexican Saints had been hit hard by the Depression, they somehow managed to accumulate enough funds to build their own chapel in 1938.

The rapid growth of Spanish-speaking missionary work in Southern California prompted Church leaders to move the headquarters of the Mexican Mission from El Paso to Los Angeles in 1929. The Church bought a large home at 2067 South Hobart Boulevard containing twenty-seven rooms, seven baths, and enough sleeping quarters for thirty missionaries. Five years later, however, Church leaders decided to return the Mexican Mission office to the more central location in El Paso. Subsequently, headquarters of the California Mission were moved from the original office at 152 West 25th Street to the larger home on Hobart.

The Mexican Mission supervised proselytizing both in Mexico and among the Spanish-speaking people of the southwestern United States. By the mid-1930s this work had grown to the point that the mission was divided along the international border. At a meeting in Los Angeles held on 28 June 1936, under the direction of Reed Smoot of the Quorum of the Twelve, a separate Spanish-American Mission was organized. The Spanish Saints in California became part of that mission, presided over by President Orlando C. Williams, whose headquarters remained at El Paso.

New Efforts in Public Affairs

With a drop in the number of missionaries during the Depression, the Church began looking for new ways to share its message. Most notably, it began to participate in mass media and public relations programs. Not since the days of Samuel Brannan had the Church involved itself so widely with the press and the community. Perhaps the recent and favorable media attention given to the Church’s welfare efforts had something to do with this participation. Both by invitation and by their own initiative, California Latter-day Saints began publishing Church literature and participating more fully in local community affairs.

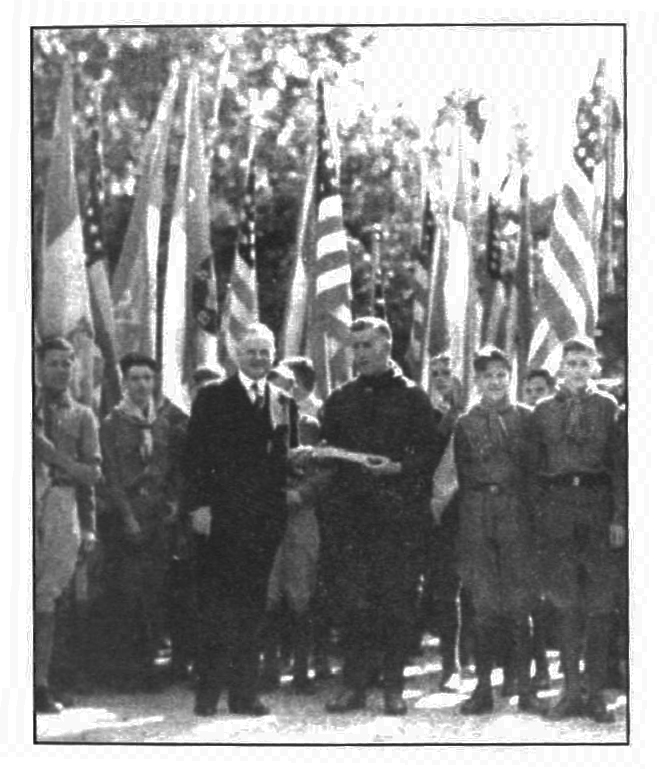

U.S. President Herbert Hoover presenting award to Howard S. McDonald,

U.S. President Herbert Hoover presenting award to Howard S. McDonald,

scoutmaster of East Bay LDS troop and future BYU President

The effort began with local Church publications, starting with the Los Angeles Stake Journal in 1924, followed by Oakland’s Messenger in 1931, then Los Angeles’s California Intermountain Weekly News in 1935. The latter two publications continued off and on for more than thirty years with the aim of increasing the efficiency of stakes and wards. [12]

Soon these efforts were expanded into the newly invented medium of radio. In 1931 a weekly radio broadcast under the direction of the stake mission president, Isaac B. Ball, started on Oakland radio station KTAB. The following year a series of discourses were delivered over Los Angeles’s KMPC by Elder James E. Talmage. The Los Angeles and Hollywood Stakes continued the KMPC programs for nearly a year.

Then, at the invitation of the Columbia Broadcasting System, the Los Angeles Stake choir was invited to perform on the weekly nationwide “Church of the Airradio program on 18 November 1934. Following the program, an invitation was extended by the Los Angeles Council of Churches to have the choir appear with other musical groups in the Easter sunrise services at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on Sunday, 21 April 1935. This began a tradition of Latter-day Saint participation in what became one of the nation’s best-known and widely broadcast Easter Sunday programs. In August 1937 the Bay Area stakes took their turn appearing on the “Church of the Air,this time being invited to speak as well as sing. The Oakland Stake president, Eugene Hilton, spoke on the significance of the Restoration. In 1938 the Church was invited to be represented at the annual Easter sunrise service at Dimond Park in Oakland, suggesting that the Latter-day Saints had finally gained “full acceptance into the religious community of the Bay Area.” [13] Elder Melvin J. Ballard spoke at the service.

Meanwhile, at the California-Pacific International Exposition in San Diego during 1935 and 1936, the Church—for the first time—erected its own exhibit building. This was under the direction of the Church’s Radio, Publicity, and Literature Committee, headed by a young, newly returned missionary (and future Church president), Gordon B. Hinckley. It was built around a shady patio, which brought a peaceful atmosphere to fair visitors. The building featured murals, stained glass, and statuary. Replicas of the Salt Lake Temple and Tabernacle outside the exhibit entrance attracted interest. Illustrated lectures on the Book of Mormon and its archaeology proved especially popular. There was also a historical parade in which the Daughters of Utah Pioneers marched in pioneer costumes. [14] Several concerts by the famed Mormon Tabernacle Choir brought additional favorable attention.

The Church was also represented in a second California fair—the Golden Gate International Exposition, held on Treasure Island in the San Francisco Bay in 1939 and 1940. Again capitalizing on the Tabernacle Choir’s popularity, the Church designed its exhibit building in the form of a “miniature Tabernacle,with a fifty-seat auditorium where missionaries presented illustrated lectures on the Church’s history and beliefs.

Yet another example of utilizing the media to tell the Church’s story was the movie, Brigham Young, which depicted the trek of the Pioneers across the Plains. In October 1939 two members of the First Presidency, Heber J. Grant and his first counselor, J. Reuben Clark Jr., went to Los Angeles to confer with producers of this film.

Temple Plans Move Forward

Depression difficulties and the expense of long-distance travel kept the California Saints yearning for their own temples. Meanwhile, these Church members made hundreds, if not thousands, of trips to Mesa in Arizona and to Salt Lake City or St. George in Utah, to do temple work. But these lengthy journeys took a toll and brought tragedy on at least two occasions.

Late Friday night, 23 February 1934, thirty-six members of the Home Gardens Ward in southeastern Los Angeles left the Mesa Temple to return home. They were traveling in a bus owned by the Los Angeles Stake Genealogical Society. Slightly after one o’clock Saturday morning, the bus encountered a sharp detour where the highway was being rebuilt. Oil-burning warning lights had been set out, but they had been extinguished by winds and heavy rain. The driver was unable to make the detour safely, and the bus overturned. Passengers were thrown about the bus, and some were ejected through doors and windows. Six passengers were killed and many others were seriously injured.

Bishop Morris R. Parry ran a mile back to the town of Aguila for help. Emergency medical crews had to come from Wickenburg—over twenty-six miles away. Meanwhile the survivors in the bus, “terrified and rain-soaked, met the perilous situation as bravely as possible.The First Presidency of the Church, at the request of the Los Angeles Stake presidency, soon appropriated funds to care for the injured. “It was several weeks before the last of [the injured] were released from the hospital.” [15]

A second tragedy occurred three days after Christmas in 1938. On the morning of 28 December two little girls and a teenaged boy were traveling by car to take part in ordinances at the St. George Temple. All three were killed on the winding road through central California’s San Marcos Pass. [16]

Until this time, progress toward a California temple had been slow. But news of these tragedies intensified interest in having temples close by. Committees were formed in both the north and the south to find suitable sites.

On 23 March 1937, despite continuing economic depression, negotiations for the purchase of a 24.33-acre site in Los Angeles were finalized. The site fronted on the heavily traveled Santa Monica Boulevard and was the property of silent screen star and comedian Harold Lloyd and his motion picture company. A large stucco building with a tile roof, which previously had been the company’s business offices, stood in the middle of the tract. When the Church purchased the property, however, this building was a fraternity house for students at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). Though preliminary plans were drawn before 1940, World War II and resulting shortages would delay the temple’s construction.

Meanwhile, the committee in the north, headed by stake president Eugene Hilton, attempted to locate the Oakland site envisioned by Elder George Albert Smith ten years before. As they searched, they were enthusiastically aided by the local chamber of commerce and city officials.

Several possible sites were considered. Though two were offered free of charge, a particular spot impressed the committee as “the one,but it was not for sale. They also faced resistance from Church headquarters after the announced purchase of the Los Angeles site, because of reluctance to build two temples in California at the same time. The committee suspended its work, but President Hilton admonished: “Let us patiently wait our time and keep silent regarding this preferred site. Let us also watch and pray that we may yet obtain it.” [17]

Other Activities during the Depression

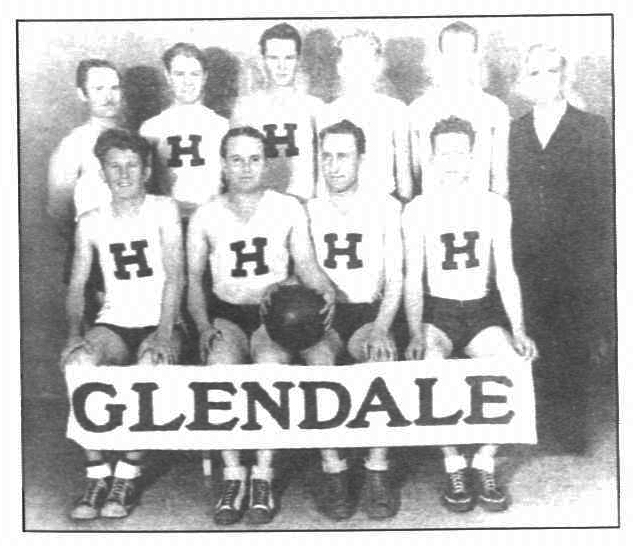

Now that California had several functioning stakes, auxiliary programs and activities mushroomed. On a dozen different fronts, Church organizations and programs became more active. One example was an active athletic program, with an annual all-Church basketball tournament in Salt Lake City, won by the Glendale Ward in 1933.

Glendale Ward 1933 all-Church basketball champions

Glendale Ward 1933 all-Church basketball champions

Depression conditions, however, posed a hurdle. In Pasadena, for example, local wards “had to wait to organize a Primary until the time when enough families could share in the transportation of the children to and from the weekly activities.” [18]

A most significant California contribution to the Church during this decade came in the area of education. In 1928, several religious denominations of the Los Angeles area had united in the inauguration of the University Religious Conference adjacent to the UCLA campus. Emily Brinton Sims became the Latter-day Saint representative. The Church contributed ten thousand dollars to the erection of the Religious Conference Building and for many years supported the operation of this institution.

A few years after the establishment of the Conference, the executive secretary, Thomas St. Clair Evans, recommended that Latter-day Saint students form an organization to promote fellowship, social and religious identification, and instruction, as the Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish groups had done. Thus, the Church’s first Deseret Club was organized at UCLA on 13 January 1931. Local members instrumental in this organization were Preston D. Richards, Adele Cannon Howells, and Vern O. Knudsen (a member of the UCLA faculty). This club was eventually expanded Churchwide on campuses where there were not enough Latter-day Saint students to justify establishing a more fully organized institute of religion.

In 1935 the University of Southern California invited the Church to send a representative to instruct classes on Mormonism in its School of Religion. Elder John A. Widtsoe of the Council of the Twelve, a former university president, received this assignment. After one season, Elder Widtsoe was succeeded by G. Byron Done, who continued for some time, developing a program that reached four thousand students in Southern California. An equally active though smaller program also flourished in Northern California. This became the foundation of the Church’s “instituteprogram in California, patterned after a similar model inaugurated at the University of Idaho in 1926.

Berkeley Institute of Religion

Berkeley Institute of Religion

One of the more curious events of the decade was the election of a California governor with Latter-day Saint roots but who openly declared himself an atheist. California’s twenty-ninth governor, Culbert Olson, began his career in Utah as a lawyer and Democratic politician, continuing it in California after 1920. He was a Utah-born grandson of Latter-day Saint Pioneers but was also a protege of the defeated Upton Sinclair. Olson was elected governor on the Democratic ticket in 1938—the first member of that party to hold the office since 1899. He was the only California governor to that date who refused to place his hand on the Bible when he took his oath of office. So Olson, who did not identify himself as LDS, was philosophically opposed to the more conservative position of the Church and his fellow Democrat, President Heber J. Grant.

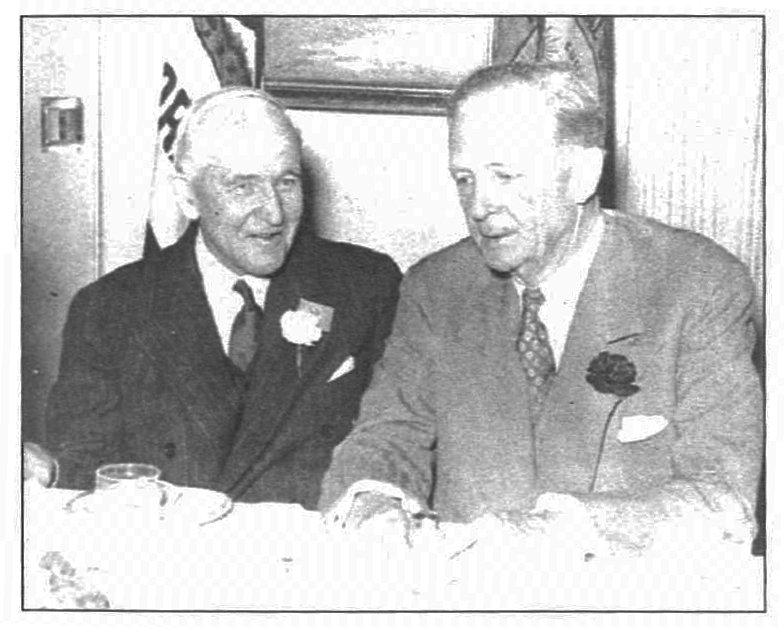

Governors Henry H. Blood of Utah and Culbert L. Olson

Governors Henry H. Blood of Utah and Culbert L. Olson

of California at 1939 Golden Gate Exposition

The decade dominated by the Great Depression was a period of suffering but also one of new beginnings and growth. The Church found a way to “care for its own.As the Saints were recognized for lives well lived, they were increasingly invited to participate in California affairs; consequently, the Church gained greater respect. In politics and on many other fronts, the Latter-day Saints were becoming a more vital and appreciated sector of California’s citizenry. For example, the Bancroft Library at the University of California in Berkeley asked the Church to submit materials on California Latter-day Saints, past and present.

Unquestionably, the Great Depression was the dominating force of the 1930s. But powerful as this effect was, events of even greater impact were about to unfold.

Notes

[1] T. H. Watkins, California: An Illustrated History (Palo Alto, Calif.: American West, 1973), 363.

[2] Lucile C. Tate, LeGrand Richards: Beloved Apostle (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982), 141–65.

[3] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:287–88.

[4] Ibid., 1:289.

[5] Messenger, May 1935, 1.

[6] In Conference Report, October 1936, 3.

[7] Deseret News, 25 April 1936, Church section, 1, 4.

[8] Susan Kamei Leung, How Firm A Foundation: The Story of the Pasadena Stake (Pasadena, Calif.: Pasadena California Stake, 1994), 19.

[9] Mission Annual Reports, 1929 and 1932; LDS Church Archives.

[10] J. Golden Kimball to the Seventies, 31 January 1934, LDS Church Archives, cited in Richard O. Cowan, The Church in the Twentieth Century (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1985), 164.

[11] Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 400–401.

[12] Messenger, January 1931.

[13] Evelyn Candland, An Ensign to the Nations: History of the Oakland Stake (Oakland: Oakland California Stake, 1992), 33.

[14] Gerald Peterson, “History of Mormon Exhibits in World Expositions” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1974), 49–53; Muir 1:461.

[15] Muir, 1:469–70.

[16] Ibid., 1:472.

[17] David W. Cummings, Triumph: Commemorating the Opening of the East Bay Interstake Center on Temple Hill, Oakland, January 1958 (Oakland: Oakland Area Stakes, 1958), 10.

[18] Leung, 4.