Challenge and Change: 1964–85

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 361–80.

The years covered in this chapter can be described as a time of challenge, change, and yet steadfastness. These were decades of protest as various groups felt that they had been left on the outside looking in and therefore sought to correct what they regarded as society’s ills. While the Church responded to these challenges, it also implemented long-planned innovations in its programs and activities to more adequately meet the needs of the Saints.

Still, Church members sought to hold steadfastly to the principles, values, and ideals which they had regarded over the years as central to their religion. Elder Bruce R. McConkie of the Quorum of the Twelve captured this feeling of steadfastness when he declared:

The Church is like a great caravan—organized, prepared, following an appointed course, with its captains of tens and captains of hundreds all in place. What does it matter if a few barking dogs snap at the heels of the wary travelers? Or that predators claim those few who fall by the way? The caravan moves on. [1]

African Americans and the Church

As California’s African American population continued to grow, Blacks joined with others in demonstrating against laws and customs regarded as discriminatory. In the mid-1960s, peaceful marches expressed the concerns of Blacks about their status in society. Some demonstrations, however, grew militant, erupting into violent riots on an unprecedented scale. The Watts section of south Los Angeles endured more than six days of urban warfare after particularly hot weather in August 1965. The carnage left forty million dollars in property damage, 34 killed, 1,032 wounded, and 3,952 arrested.

Because LDS practice long held that Blacks could not hold the priesthood, some militants began targeting the Church and its members. Even though the First Presidency issued a proclamation in 1964 that the Church supported all citizens in their quest for civil rights, many were still not satisfied. Several universities, including Stanford in California, refused to participate in athletic events with Brigham Young University, whose teams were sometimes threatened with violence. Bert Scoll, a member of the Los Angeles Stake high council, watched the destruction of his medical clinic on television even as it happened. A curfew imposed by the police canceled all Wilshire Ward meetings. Even after the curfew was lifted, members felt unsafe in the area at night, so all meetings were held during daylight.

Some time after these demonstrations of protest had subsided, concerned Church leaders continued giving the question of Blacks holding the priesthood deep consideration. Over a period of months in 1977 and 1978, the General Authorities discussed this matter in their regular temple meetings. In addition, Church president Spencer W. Kimball frequently went to the Salt Lake Temple, especially on Saturdays and Sundays when he could be there alone, to plead with the Lord for guidance.

Then, on 1 June 1978, the First Presidency and the Twelve gathered, fasting, for their regular monthly meeting in the temple. After a two-hour session during which each had expressed at length his feelings, there seemed to be a remarkable unity. President Kimball asked them to unite with him in prayer. One of the apostles, Elder Bruce R. McConkie, recalled:

It was during this prayer that the revelation came. The Spirit of the Lord rested mightily upon us all; we felt something akin to what happened on the day of Pentecost and at the dedication of the Kirtland Temple. From the midst of eternity, the voice of God, conveyed by the power of the Spirit, spoke to his prophet. . . . And we all . . . became personal witnesses that the word received was the mind and will and voice of the Lord. [2]

Others present concurred that none of them “had ever experienced anything of such spiritual magnitude and power as was poured out upon the Presidency and the Twelve that day in the upper room in the house of the Lord.” [3] The Church’s official announcement affirmed that priesthood blessings would henceforth be given to all “regardless of race or color” (Doctrine and Covenants, Official Declaration 2).

When the revelation was publicly announced, members everywhere rejoiced, particularly Black members: “It’s the greatest thing that has happened to the Black man since we have been in this life,” declared Paul Devine, a high school physical education teacher from San Pedro. He added that the first thing he wanted to do after receiving the priesthood was baptize his children. Robert and Delores Lang, already carrying leadership responsibilities in the Inglewood Ward, were thrilled with the announcement. “When I came in, my wife was crying,” Robert reported. “She had heard the news and was so happy. . . . Delores and I will now get our endowments and will be sealed and do temple work for the dead. I know that they have been waiting for this moment, too.” [4]

Youth and the Counterculture

African Americans were not the only ones working for changes in society. California college campuses also became focal points for protest. Although most students of the “baby boomer” generation had been raised in relative prosperity, many were unhappy and disliked what they regarded as California’s prevailing materialism. The well-scrubbed look of the 1950s gave way to an unkempt “counterculture” identified with tattered clothes, sandals, beads, and long hair. Many of these young people indulged in mind-altering drugs and viewed traditional religion as irrelevant. They also espoused their own set of morals, as the birth control pill seemed to replace abstinence, and casual sex became widely accepted. Many, raised under a constant threat of nuclear holocaust, opposed America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Many California youth rebelled and refused to serve in the U.S. military.

The Vietnam War became a deeply emotional and political issue; and as with the rest of the nation, the Saints were divided. While some opposed the war, Latter-day Saint George F. Putnam, a leading Southern California television commentator, reflected the feelings of many other Church members as he vigorously spoke out against those who were burning draft cards and desecrating the U.S. flag. [5] A quota in each LDS ward stipulated that only two draft-eligible young men could be called on missions each year. This placed a burden on the shoulders of stake and ward leaders who had to decide who could go and who could not.

Some LDS youth left home without telling their parents where they were going and went to California to gather with other “hippies.” Urban stake leaders sometimes received ten to fifteen contacts a month from concerned parents asking for help in locating lost children. Bishops of wards where these youth gathered spent many extra hours, often in hostile environments, trying to locate young adults and teens.

While some Latter-day Saints felt it was best to try to understand these youth, others were shocked and felt that anyone who showed any sympathy was spiritually disloyal. However, most leaders recognized that simply choosing to dress differently or to listen to popular music was not contrary to God’s commandments, and that those involved were souls to whom they needed to minister. Still, the Church’s established standards had to be maintained, and when it came to more important issues, such as drug use or premarital sex—behaviors clearly contrary to the commandments of God—leaders stood steadfast.

Challenges to Traditional Family Roles

The traditional family with a father, mother, and several children became increasingly less common. As smaller families became the norm of society, larger LDS families sometimes became the objects of disapproving whispers at supermarkets and shopping malls. Single-parent households—usually mothers with children—became more common as the divorce rate grew. Perhaps the most direct threat to the family came from the growing practice of couples living together outside of marriage. Many, including influential celebrities, openly questioned the benefits of marriage for themselves and their children.

During these years, feminists challenged the traditional roles of women. Strident voices insisted that those roles were demeaning and intended only to keep women subservient to men. Sonia Johnson, an English professor who had left her family and the Church and received much notoriety, insisted in a speech at San Jose State University that “there is no word in our language strong enough to describe the utter horror of most women’s lives with men.” She boasted that the day she was excommunicated from the LDS Church was “the greatest day in her life.” [6]

The Church acted to meet the changing needs of women. As more and more women became employed during the daytime, evening Relief Society sessions were added. The General Authorities encouraged local leaders to invite women to speak and pray more often in Church meetings and to involve them more fully in planning programs and activities. Members of the general Relief Society, Young Women, and Primary presidencies were regularly invited to speak in general conferences. To help strengthen the family, the Church instituted a yearly women’s meeting that coincided with the October general conference and was broadcast from the Salt Lake Tabernacle via satellite to local stake centers in California and around the world.

Despite these developments, the major objectives of radical feminists still were not met. The policy concerning women holding the priesthood was not modified. Someone confronted Sally B. Nielson, who served twenty-three years in the Pasadena Stake Relief Society presidency: “Well 1 don’t understand how you can belong to that church and be belittled as a woman because you can’t hold the priesthood.” Her response was: “Who needs the priesthood? Being honored as a woman by the priesthood is the most wonderful thing a woman could ask for. In all the years I have served, I have never felt that one priesthood holder set himself up as my superior.” [7]

Further, the Church took a stand against the proposed “Equal Rights Amendment” to the United States Constitution, which would have banned gender-based legal distinctions. Church leaders feared that it would abolish laws giving special protection to women and thereby undermine traditional family structures and roles.

At the first of the annual women’s conferences in 1978, President Spencer W. Kimball affirmed: “Much is said about the drudgery and confinement of the woman’s role in the home. In the perspective of the gospel it is not so. There is divinity in each new life. There is challenge in creating the environment in which a child can grow and develop. There is partnership between the man and woman in building a family which can last throughout the eternities.” [8]

Many LDS women in California echoed those sentiments. Helen Andelin of Santa Barbara appeared several times on nationwide television programs to defend the traditional role of women in the family. Similarly, Colleen Pulley of Concord mobilized a group of other Latter-day Saint women to urge the state textbook commission to retain the image of women being happy in their “prime role” as “wives and mothers and teachers of the next generation.” [9]

Another threat to the traditional family came from an increasingly vocal homosexual movement. Animosity toward the Church grew among some who viewed its policy on morality as archaic and discriminatory. As early as February 1973, Church president Harold B. Lee branded homosexual conduct as a “grievous sin” in the same degree as adultery and fornication. [10]

As homosexual activists continued protesting, Church members sometimes became involved in defending the stance of the Church. In San Jose, for instance, activists placed before the local voters an initiative granting a city-sponsored “Gay Pride Week.” Some of the Church’s earliest formal interfaith efforts in that city came as Latter-day Saints joined with other religious groups to oppose the initiative, which was subsequently defeated by the voters.

Adjustments in Meeting Patterns and Programs

In response to the challenges of modern times, the Church took several far-reaching steps. “We are in a program of defense,” declared Elder Harold B. Lee of the Quorum of the Twelve in 1961. “The Church of Jesus Christ was set upon this earth in this day ‘. . . for a defense, and for a refuge from the storm, and from wrath when it should be poured out without mixture upon the whole earth’ (D&C 115:6). [11] To this end, and under Elder Lee’s direction, Church authorities examined carefully the interplay among, and perhaps unnecessary duplication of, various programs to be sure these activities were helping the Saints meet their challenges. Long and prayerful planning resulted in what became known as the Church’s priesthood correlation program.

Prior to 1964, several different Church organizations were involved in visiting families in their homes. All these contacts were now consolidated under home teachers, who were assigned to visit each family monthly and minister to its needs. To further strengthen the Saints, the Church published its first family home evening manual in 1965. It provided lessons for parents to teach and included suggestions for a variety of family-centered activities. Five years later, Monday nights were freed from all other Church activities so families could have this time together.

Further steps were taken to facilitate the coordination of Church activities. Priesthood executive committees and correlation councils were established at the ward and stake levels. Youth age groupings were adjusted to be the same from one organization to another. In the process, such long-established names as M Men and Gleaners gave way to the more descriptive designation, Young Adults. Calendars were synchronized to have all organizations begin their curriculum years at the same time. Rather than having each organization publish its own magazine, in 1971 the Ensign replaced the Improvement Era and other publications as the Church’s periodical for adults.

The energy shortage of the 1970s provided the setting for carrying out yet another long-anticipated move. For decades, the priesthood and Sunday School met Sunday mornings, sacrament meetings convened Sunday afternoons or evenings, and Primary activities and Relief Society meetings were conducted during the week. However, in the early 1970s several local units, including Los Angeles’s Spanish Branch, adopted a consolidated schedule with all meetings except youth activities on Sunday. Meetings were scheduled back-to-back to better serve these Saints, some of whom came great distances.

A similar three-hour block of meetings began Churchwide in March of 1980. Not only did this cut energy costs for transportation, heating, and air conditioning, but it also gave Church members more time for families, service, and community involvement. The benefits of this consolidation were especially great in California, where Latter-day Saints typically traveled some distance to attend church meetings. [12]

Helping Groups with Special Needs

During these years the Church also devised programs to serve members with special needs. California played a leading role in these developments.

Many deaf people had come to Southern California during World War II because they could work comfortably in noisy defense industries. As early as 1941, a special Sunday School class for the deaf was organized in the Vermont Ward of the South Los Angeles Stake. A deaf branch was formed eleven years later in the more centrally located Los Angeles Stake. Over the years, Church units in other areas sponsored programs for deaf members. The Oakland-Berkeley Stake, for example, organized a softball team of deaf players. [13]

Oakland-Berkeley Stake deaf softball player and coach

Oakland-Berkeley Stake deaf softball player and coach

In 1968, the first deaf mis- sionaries in the Church were called to serve in Los Angeles. Within a year, eighteen conversions were made, including two brothers who were deaf, blind, and could not speak. Through a “slow, laborious process,” the missionaries taught these brothers by drawing out in the palms of their hands the letters of the alphabet. After their baptisms “the two, with tears streaming down their faces, embraced each other and then the missionaries who had so lovingly and painstakingly taught them the gospel.” Soon “they were given the priesthood and, with the assistance of a member of the branch who could see, began to pass the sacrament.” With the assistance of such missionary work, the deaf branch grew in membership to almost three hundred. [14]

Southern California played a key role in Churchwide work with the deaf. During the summer of 1972, the Church’s Social Service Department conducted a twelve-day seminar at California State College in Northridge for deaf Latter-day Saints and their interpreters. Together, they planned a dictionary of signs for unique LDS terms. A film on how to perform sacred ordinances when one cannot speak attracted special interest. [15]

Another group with special needs, particularly in urban areas, was the large number of single members. People were marrying later and divorcing more; men were also dying sooner than women, leaving more and more singles, young and old. Even suburban and rural wards often had more than most members realized. The mobility of some members created challenges for leaders. In the Pasadena Ward, for example, there were 429 personnel changes in ward administration in one year. [16]

Singles and seniors needed special consideration. With priesthood correlation’s emphasis that all Church programs should focus on and strengthen families, some single adults wondered where they fit in. The Los Angeles Stake led the way in developing a program for them. The problem was addressed as early as 1946, when Bishop Jay Grant began “Get Acquainted” firesides and socials for singles in his Wilshire Ward.

A quarter of a century later the stake leadership gave new emphasis to this activity, providing the basis for a Churchwide single adult program. In March 1969 stake leaders discussed with General Authorities the possibility of establishing a singles ward. President Harold B. Lee, who had a special affinity for single members, explained, “We have been neglecting some of our adult members—those over eighteen who have not yet found their companions, or who are perhaps widowed or divorced. They have been saying to us, ‘But you have no program for us. . . .’ We have said to them ‘We want to find out what you need.’” [17]

Finally, on 27 January 1974, at a special meeting of the UCLA Ward, “the first singles unit outside Salt Lake City” was organized. Branch leaders “found that almost half were attending Church for the first time in their adult lives. . . . Between 1979 and 1984 seventy-eight marriages took place between branch members.” [18] Soon singles wards were organized in many other California stakes.

Another challenge facing widely scattered California Latter-day Saints was how to make seminary instruction avail- able where there were not enough students, where distances were great, or where there were no Church buildings. The answer came in 1966. The young people studied seminary lessons at home during the week and then met as part of their regular Sunday meetings to go over this material with a volunteer teacher. In 1972 the program was expanded to include college-level institute study as well.

Sharing the Gospel

During the difficulties of the 1960s and the 1970s, Latterday Saints felt more than ever that the gospel had the answers society needed, and they were eager to share it with their neighbors. However, communicating with California’s diverse population posed a significant challenge, but modern technology could help. President Spencer W. Kimball remarked, “When we have used the satellite and related discoveries to their greatest potential and all of the media—the papers, magazines, television, radio—all in their greatest power . . . then, and not until then, shall we approach the insistence of our Lord and Master to go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.” [19]

These words reinforced an effort that had already been underway for some years. In 1968 the Church had purchased Southern California’s radio station KBIG-AM and -FM. [20] The Church also acquired station KOIT-AM and -FM in San Francisco.

Following the creation of the Church’s Public Communications Department in 1972, a full-time public affairs office was opened in Los Angeles. Keith Atkinson, a media professional, was hired to head this office. During the next two decades he built a public relations network that culminated in a public affairs council in nearly every stake. Through these efforts, local members were able to raise public awareness of the Church, answer questions, and build bridges of understanding.

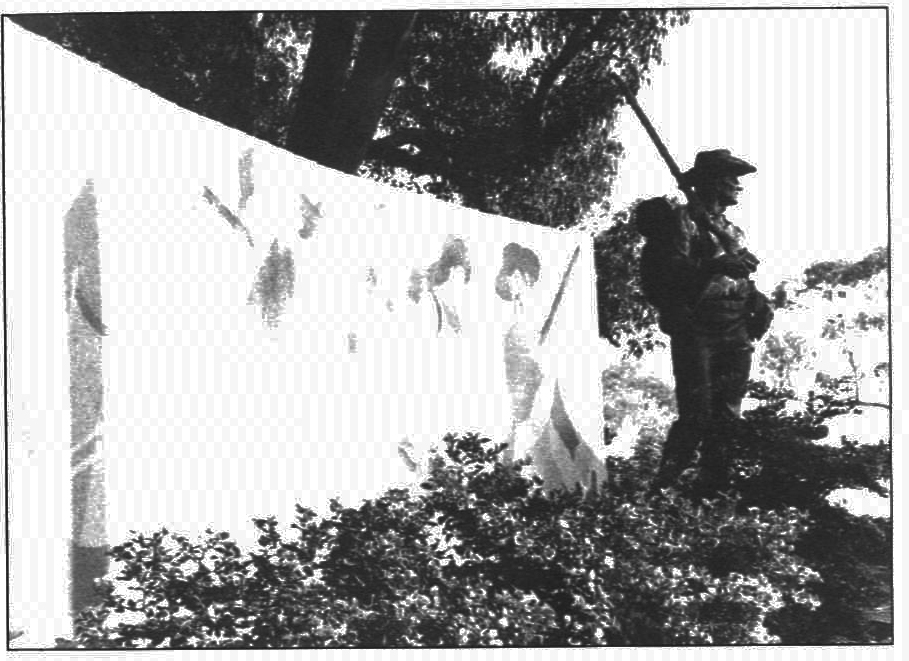

As Latter-day Saints recalled past achievements, they discovered new opportunities to share their message. On 22 November 1969, Hugh B. Brown of the First Presidency dedicated a nine-foot bronze statue of a Mormon Battalion soldier by LDS sculptor Edward J. Fraughton. This monument stood atop a wooded hill in San Diego’s Presidio Park, not far from where the Battalion had completed its historic march nearly a century and a quarter earlier. It was paid for through a variety of projects conducted by California chapters of the Sons of Utah Pioneers (SUP). [21]

Edward Fraughton's statue of Battalion soldier in Presidio Park, San Diego

Edward Fraughton's statue of Battalion soldier in Presidio Park, San Diego

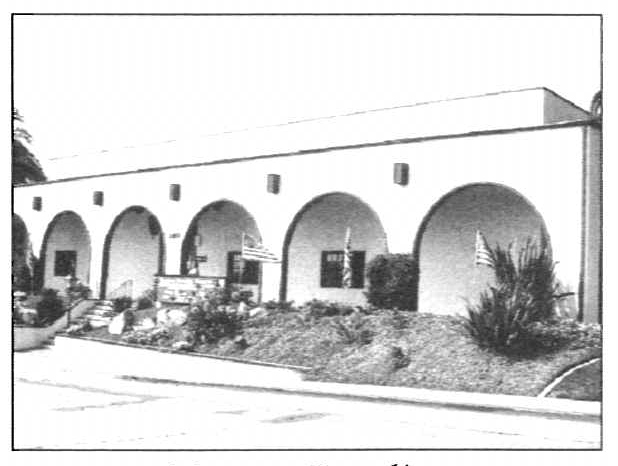

Three years later, on 3 November 1972, Church president Harold B. Lee dedicated the Mormon Battalion Memorial visitors center. This one-story building of traditional Spanish American architecture was built in San Diego’s “Old Town,” just a few hundred yards from Presidio Park. Its displays reminded visitors that the Battalion soldiers were the first to introduce the restored gospel to Southern California and that the Latter-day Saints were a patriotic people loyal to their country. [22]

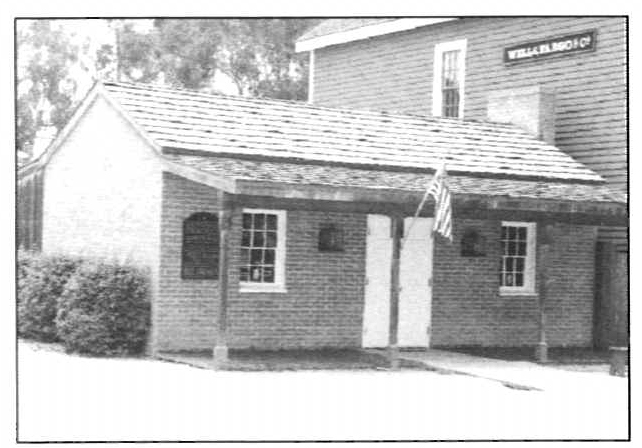

Mormon Battalion visitors center at Old Town in San Diego

Mormon Battalion visitors center at Old Town in San Diego

Another opportunity to focus on the Mormon Battalion’s contributions came with the restoration of nine buildings in the San Diego historic district. While six of the structures were rebuilt with public tax funds, the restoration of the old courthouse was paid for by private groups. These groups included local legal associations and the Utah-based Mormon Battalion, Inc., which raised one hundred thousand dollars. Originally erected by Battalion men, this building was destroyed by fire in 1872. The restoration was aided when nearby excavations unearthed old bricks the soldiers had made for the original structure. [23]

Reconstructed courthouse at Old Town in San Diego

Reconstructed courthouse at Old Town in San Diego

Also in Northern California, attention was directed to early Latter-day Saint history. In 1971 the “Mormon Boys’ Cabin” was moved from high in the mountains to become a permanent part of the historic park at the gold-discovery site (see picture in chapter 22). The restoration was a joint venture of the U.S. Forest Service, the California State Department of Parks and Recreation, and the SUP. [24] The wagon road first carved out over Carson Pass in 1848 by homeward-bound Mormon Battalion veterans was designated as a historic trail in August 1992. In October of the following year, a nearby mountain was officially named “Coray Peak” by the U.S. Board of Geographical Names, honoring Melissa Coray, who traveled with the Battalion road builders. On 30 July 1994 the SUP unveiled a plaque in the pass commemorating the accomplishments of the 1848 group. [25]

The Church explored yet other means of reaching the public. Beginning in the 1970s, thousands of beautiful Christmas lights were installed on the grounds at both the Los Angeles and Oakland temples to commemorate the light that was brought into the world with the birth of Jesus Christ. Mayors of both cities began visiting the temple grounds each year in order to turn on the lights and deliver a Christmas message to their respective communities.

Pageants also became an important means of sharing the Church’s message. The Mormon Battalion’s exploits were recalled in My San Diego, a musical production written by R. Don Oscarson. This pageant was presented each night for a week during October 1977 in Balboa Park’s Starlight Bowl. [26]

The Oakland Temple pageant, And It Came to Pass, was another attempt to reach out to those outside the Church. Originally performed on Temple Hill in the 1960s, the pageant portrayed the apostasy from the New Testament Church, the latter-day Restoration, and the Pioneer trek to Utah. It was first presented annually in the Center, then in Oakland and San Jose on alternate years, then every three years. Initially written to tell the Church’s story to non-LDS audiences, the pageant became immensely popular as a testimony builder for Church youth.

Meanwhile, Pasadena’s famed New Year’s Day Rose Parade became another opportunity for the Church to share its message. The Pasadena Stake was represented over the years by many Eagle Scout honorguards, and in 1970 Pam Tedesco reigned as parade queen, the only Latter-day Saint to do so. Then in 1976 a local Los Angeles LDS public communications council entered a family-oriented float in the famed parade. Individual contributors donated thirty-five thousand dollars to pay for the float, and five hundred volunteers worked many hours gluing thousands of rose petals, orchids, camellias, and chrysanthemums to its surface. The float’s message, “The Family Is Eternal,” was received not only by the million who lined the parade route but also by other millions of television viewers worldwide. [27] Another float the following year, entitled “Family Home Evening,” featured the popular Osmond family, professional Latter-day Saint entertainers. [28] A third float in 1978 carried seven children representing different ethnic cultures to illustrate the theme “I Am a Child of God,” [29] taking the words of Pasadena Saint Mildred Pettit’s song to the world. These were the first floats from any church accepted by parade officials since 1926.

In keeping with the family theme, in 1977 the Church produced and aired a national television program entitled “The Family and Other Living Things,” again featuring the Osmonds and other popular entertainers. Viewers were invited to write or call for a free brochure (a condensed version of the Church’s family home evening manual) to help them with family relations. This was the Church’s first attempt at inviting viewer response from a national television program, and it was followed by others to various targeted audiences over the ensuing years. About a decade later when the Church produced another television special, “Together Forever,” hundreds of Southern California LDS volunteers, by means of personal visits, phone calls, or announcements left on doorknobs, invited nearly a half million people to watch the program. These efforts not only resulted in hundreds of missionary referrals but also brought a greater feeling of unity between missionaries and local Saints. [30]

Another media success was the Brigham Young University football team, which won widespread prominence, including a national championship in 1984. The team’s participation in internationally televised post-season bowl games became an annual event. BYU’s first appearance at San Diego’s Holiday Bowl in December 1978 attracted President Spencer W. Kimball, who addressed approximately seventeen thousand people at a pregame devotional on the subject of “putting Christ back into Christmas.” [31]

Keeping in Touch with the Saints

While the Church was attempting to communicate with a non-LDS public, its own members were not forgotten. In 1981, the Church installed satellite receiving stations in each of its stake centers, including those in California. In addition to general conference broadcasts, which up to this point had been carried live by only a few local television operators, these receiving stations made it possible for the Saints to attend Churchwide firesides and instructional programs and to watch live broadcasts of BYU sports events at local stake centers. Now, for the first time, California Church members could experience the spirituality of a General Authority’s talk, the beauty of Temple Square in Salt Lake City, or the excitement of a BYU team’s or athlete’s victory.

To deliver their messages to ever-growing and more diverse Church audiences, Church leaders began conducting meetings for larger groups of Latter-day Saints. In May 1980 an area conference was held at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. Two apostles originally called from California, Howard W. Hunter and David B. Haight, accompanied President Kimball and other general Church leaders to the conference, which resulted in the largest gathering of Latter-day Saints in history as nearly eighty thousand attended the Sunday conference, which was translated into seven languages. Since regular attendance at the multiplying number of local stake conferences was now a physical impossibility for the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, many members felt that this might be the only chance in their lifetimes to see and hear their prophets and apostles in person.

In his keynote address, President Kimball stressed the need for reaching out with the gospel message to every individual, family, neighborhood, and cultural and ethnic group. [32] “It is not left to our discretion or to our pleasure or to our convenience. Every man and woman should return home from this conference with the determination that they will take the Gospel to their relatives and their friends.” [33]

This was followed by a series of smaller area and regional conferences throughout California, including one of the first two multi-stake conferences in the United States, which was held at San Diego on 8 January 1984. This conference was conducted by Elders Howard W. Hunter and James E. Faust of the Quorum of the Twelve and Robert L. Backman of the Seventy, who would be appointed just a few months later as Area President of California. [34]

The attendance record set at the 1980 Rose Bowl conference was surpassed by attendance at an LDS dance festival held five years later at the same location. More than one hundred thousand people attended, setting a new record for Latter-day Saints at a single event. U.S. president Ronald Reagan sent a telegram to the performers, commending them and their leaders for a “commitment to excellence.” [35]

Holding Steadfast

Out of the turbulent 1960s and 1970s came a hope for a brighter future as the Saints lived and shared the gospel of Jesus Christ. The Church’s progress in California was reflected in the organization of new stakes. Because these units, headed by local leaders, are net givers rather than receivers of Church resources, their creation indicates real Church progress better than does a mere increase in membership. Quietly, and almost unnoticed, the formation of the Palm Springs Stake in 1967 meant that Isaiah’s figurative tent was stretched and staked over the entire state of California. No matter where in the Golden State they lived, Latter-day Saints now were “gathered into stakes” (D&C 115:5–6) and had the benefit of more complete involvement in the Church’s programs and activities.

Although the latter part of the twentieth century brought many challenges, the Saints steadfastly held to their basic principles and continued to move forward. While responding to the needs of ethnic minorities and other groups, the Church would seek additional opportunities to reach out to an even broader audience.

Notes

[1] Ensign, November 1984, 85.

[2] Bruce R. McConkie, “The New Revelation on Priesthood,” in Priesthood (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981), 126–28.

[3] Ibid., 128.

[4] Church News, 17 June 1978, 3–4.

[5] Ibid., 4 July 1970, 14.

[6] Notes taken by William E. Homer.

[7] Susan K. Leung, How Firm a Foundation: The Story of the Pasadena Stake (Pasadena, Calif.: Pasadena California Stake, 1994), 51.

[8] Ensign, November 1978, 105–6.

[9] Church News, 18 December 1971, 6; 4 January 1975, 13.

[10] Ensign, January 1973, 106.

[11] In Conference Report, October 1961, 81.

[12] Church News, 9 February 1980, 3; 8 March 1980, 3.

[13] Ibid., 23 September 1972, 6.

[14] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 248.

[15] Church News, 19 August 1972, 7, 12.

[16] Leung, 53.

[17] Harold B. Lee, Ye Arc the Light of the World (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 349.

[18] Orton, 272–74.

[19] Regional Representatives Seminar, 4 April 1974.

[20] Church News, 20 April 1968, 2.

[21] Ibid., 27 April 1968, 3; 29 November 1969, 8–9,14.

[22] Ibid., 22 April 1972, 6; 11 November 1972, 3,10.

[23] Ibid., 23 May 1981, 7; 28 November 1992, 7.

[24] Ibid., 12 June 1971, 6.

[25] Ibid., 13 August 1994, 3–4.

[26] Ibid., 22 October 1977, 13.

[27] Ibid., 20 September 1975, 3; 10 January 1976, 5.

[28] Ibid., 20 November 1976, 4; 8 January 1977, 8–9, 12.

[29] Ibid., 7 January 1978, 3.

[30] Ibid., 12 August 1989, 5.

[31] Ibid., 30 December 1978, 4–5.

[32] Ibid., 24 May 1980, 4–5.

[33] Remarks at Rose Bowl Area Conference, May 1980.

[34] Church News, 15 January 1984, 4.

[35] Ibid., 28 July 1985, 12.