Celebration and Commemoration: 1945–1955

Cowan, Richard O. and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 317–336.

The years immediately following World War II were a time of celebration. Latter-day Saints rejoiced as peace superseded war, and they commemorated various pioneer centennials as worldwide Church membership surpassed the one million mark in 1947.

In California, Latter-day Saints were once again, as Samuel Brannan had expressed it over a century earlier, “A No. 1 in this country.” [1] Press coverage continued to be positive. State politicians made increasingly frequent appearances at LDS events.

Presiding over the Church after the war years was President Heber J. Grant’s successor, George Albert Smith, who was a lifelong devotee of Church history, especially the marking of historic sites. President Smith supervised the erection of more than a hundred substantial markers at historic sites throughout the western United States, several of which were in California. Thus, it was fitting that he presided over the Church during this time of commemoration.

President Smith stood six feet tall and was slender with a thin face and a kindly expression. He was without guile or pretense. One Californian, while investigating the Church, attended a meeting where the prophet was going to be. Expecting to see a pompous and impeccably dressed man, he was completely disarmed by President Smith’s quiet, approachable, and loving manner and said he was convinced that George Albert Smith was a true and humble servant of God when he noticed that his shoes were an inexpensive department store variety with holes in the soles.

Though he never resided in California, President Smith had visited the state on numerous occasions. His 1924 vision of the future Oakland Temple imbued the Saints with a heightened desire for temples. During his administration, plans for building California temples in both the north and the south were vigorously pursued, though he died before either was completed.

Postwar Growth in California

LDS growth in California continued during the postwar years, passing the one hundred thousand mark in 1950. Many service people passed through the state on their way home from Pacific battlefields, and some never left. Others returned to the Intermountain area, then came back with families or sweethearts to settle.

New cities sprang up as the state teemed with new subdivisions of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of identical two and three-bedroom homes. The G.I. Bill allowed returning service people to purchase one of those starter homes with no money down and low monthly payments, while earning a living as laborers, businessmen, or professionals, often using skills they had gained in the service.

California made a strong commitment to education, and many Latter-day Saints, both students and educators, benefitted. Through the G.I. Bill, the federal government also paid for veterans’ college educations. In order to meet educational needs in California, a widely admired system of state and community colleges developed. At the same time, the population growth and the postwar baby boom required many new public schools.

As the school system grew, more teachers and administrators were needed. Recruiters from California were frequent visitors at Utah colleges, resulting in “a surprisingly large number of Latter-day Saint teachers and administrators in higher education” in California, as well as hundreds of teachers in California public schools, and hundreds more studying in California colleges. [2]

Of the 1,234 Latter-day Saints whose biographies were published by Leo J. Muir in 1952,29 percent were businessmen, 17 percent educators, and 23 percent other professionals. Nearly three-fourths came from Utah or other Intermountain states. Only 10 percent, mostly young adult children of transplants, were born in California. Apparently, sixty years of active proselytizing in the Los Angeles area had not resulted in significant numbers of native converts. Only 150—12 percent of Muir’s sample—were converts. Less than fifty were California- born.

Historical Societies and Centennial Celebrations

With the heavy migration into California during the Great Depression and then during World War II, an increasing number of residents in the Golden State were first-generation transplants from other areas. During the postwar years it was natural for these people to look back to their roots. Various societies sponsored activities “designed to bring former residents of individual states together in a kind of continuing reunion.” [3] This interest in places of origin was strongly manifested among the California Saints, who created several Utah-oriented organizations. The Daughters of Utah Pioneers (DUP) was perhaps the most active; from their beginning at Los Angeles in 1927, they continued organizing chapters in virtually every California stake. The first chapter of the Sons of Utah Pioneers (SUP) was organized on 28 October 1946, also in Los Angeles. Other groups included the California Utah Women and the Utah Women’s Club. These LDS men and women constituted some of the most civic-minded groups in the state.

These societies became active in celebrating the Latter-day Saints’ California heritage. On 30 July 1940 the San Francisco DUP chapter brought ninety-five-year-old Elizabeth Bird Howell, the only living survivor of the Brooklyn passengers, to be present as a bronze plaque was unveiled at the corner of Broadway and Battery Streets in San Francisco, the spot where the ship had unloaded. [4]

Although Latter-day Saint settlers arrived in California in 1846—a full year before the Pioneers entered the Great Basin—and although San Francisco was the first LDS settlement in the West, these facts went largely uncelebrated, even among local members. Instead, the arrival of the Pioneers in Utah in 1847 was the main focus.

San Bernardino’s “Covered Wagon Days” featured a performance by the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir. Participating in the celebration were President George Albert Smith and Utah governor Herbert Maw. On Sunday, 12 October, the Choir presented its 950th consecutive weekly radio broadcast, from San Bernardino’s First Congregational Church. Elder Richard L. Evans, member of the First Council of the Seventy and official narrator for the Choir, conducted the proceedings. Other churches in the community were closed that day as the Choir program was designated “The Union Church Service.”

On 24 January 1948 Latter-day Saints participated in the “Gold Discovery Jubilee” at Coloma. From Church headquarters in Utah came Oscar A. Kirkham of the First Council of the Seventy, Gordon B. Hinckley of the Church Publicity Committee, and Henry Smith of the Deseret News. Grover C. Dunford, Los Angeles SUP president, presented Governor Earl Warren a memento, “a pair of handsome bookends, each a replica of the Mormon Battalion Monument on the Utah State Capitol grounds in Salt Lake City.” [5] For this occasion local Church members erected a replica of a typical miner’s cabin built of “random width boards and batten” to house a special exhibit. Prepared under Brother Hinckley’s supervision, illuminated dioramas focused on the Mormon Battalion’s achievements, including their role in the discovery of gold. [6]

The Alameda County DUP chapter raised money and in October 1949 erected two monuments in the San Joaquin Valley. Designed by Theodore Ruegg, an LDS architect from Berkeley, each consists of metal plaques mounted on cobblestone shafts (see appendix E for locations). The inscription on the monument at Ripon commemorates the New Hope Colony, where “Mormon Pioneers from the ship Brooklyn founded first known agricultural colony in San Joaquin valley,” and planted the “first wheat.”

The second marker, placed at the former site of Moss Landing on the San Joaquin River, honors Samuel Brannan’s sailboat, the Comet, the “first known sail launch to ascend San Joaquin River from San Francisco.”

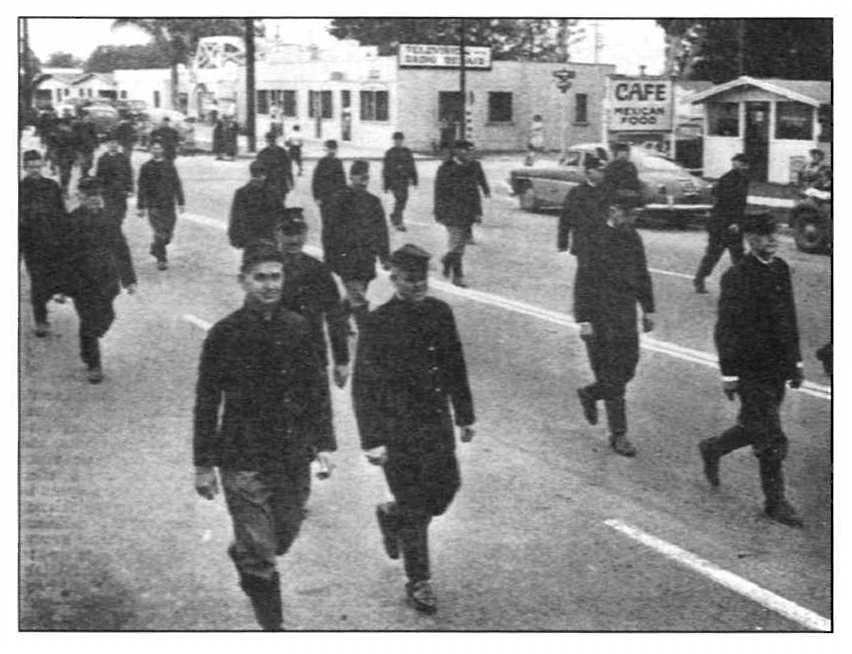

The SUP celebrated the centennial of California’s statehood in 1950. In March of that year, members of the Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Bernardino SUP chapters joined others who had come from Utah in several buses, traveling over the final portion of the Mormon Battalion route into California. In Los Angeles, President George Albert Smith, Utah governor J. Bracken Lee, and apostles Joseph Fielding Smith and Harold B. Lee greeted them.

SUP "Mormon Battalion march" at San Diego

SUP "Mormon Battalion march" at San Diego

Governors Earl Warren and J. Bracken Lee admire

Governors Earl Warren and J. Bracken Lee admire

gold discovery statue with sculptor Avard Fairbanks

Before a crowd of fifteen hundred on the south lawn of the city hall, they were officially received by Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron and California governor Earl Warren. Avard Fairbanks, the noted Utah sculptor, presented to the governor “a miniature of the monument he had made to memorialize the discovery of gold in California’

President Smith then addressed the throng and “recounted the achievements of the Battalion.” He also “related many interesting personal experiences in California” and “expressed praise and appreciation to the people of California for their goodwill” toward the Latter-day Saints. He then “out- lined his formula for the cure of the evils which perplex the race of men.” [7]

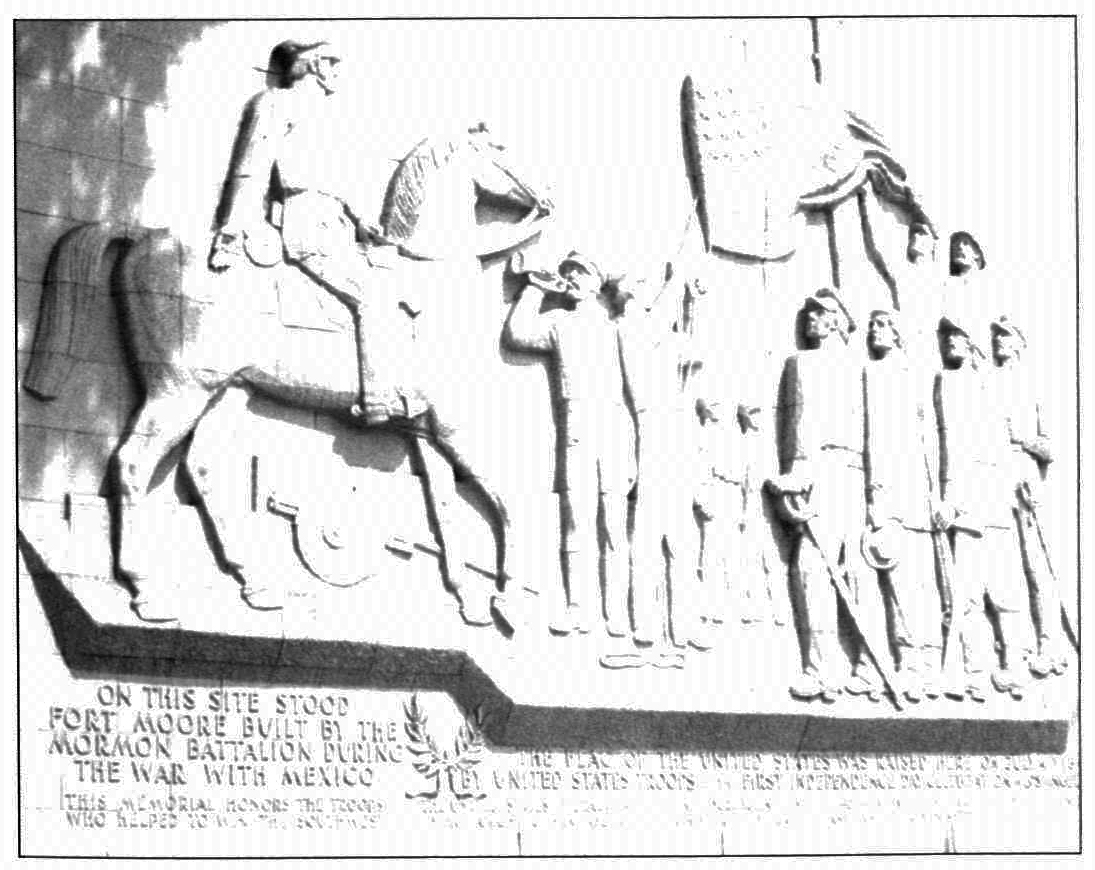

Members of the DUP and SUP had, over a period of several years, raised funds for a monument to the Mormon Battalion that would stand adjacent to the Los Angeles civic center. Construction of the Hollywood Freeway just after the close of World War II required the removal of part of the hill on which Fort Moore had stood. As part of a massive retaining wall (four hundred feet long), the memorial features relief sculptures of early California pioneers, including the Battalion. A sixty-eight- foot pylon flagpole bears the inscription: “Fort Moore Pioneer Memorial To the Brave men and women who, with trust in God, faced privation and death in extending the frontiers of our country to include this land of promise.” The monument was finally dedicated on 3 July 1958 by former LDS Serviceman’s Coordinator Hugh B. Brown, now a member of the Quorum of the Twelve and a grandson of Battalion member and gold discoverer James S. Brown. [8]

Ft. Moore memorial in Los Angeles

Ft. Moore memorial in Los Angeles

Leo J. Muir’s two-volume work, A Century of Mormon Activities in California, was published during this period of intense interest in Church history. The first volume briefly reviewed Church activities in the Golden State, while the second volume contained over one thousand brief biographical sketches. A major contribution of Muir’s 1952 work was his collection of many interesting photographs. Another significant California LDS history was Eugene E. Campbell’s doctoral dissertation at the University of Southern California, also completed in 1952. [9]

Latter-day Saints in Cultural and Professional Life

As the Latter-day Saints gained increasing respect, they became more accepted into California’s cultural and professional circles. These were years of celebrity-studded fund raisers, elegant gold-and-green balls, and formal concerts. For example, on 18 November 1949, the Inglewood Stake presented a “grand musical” in Los Angeles’s prestigious Shrine Auditorium as a welfare fund raiser. Many noted performers responded to invitations to volunteer their talents. The production featured well-known Latter-day Saint performers, including movie star Lorraine Day. Also in attendance were Cecil B. DeMille, Gary Cooper, Edgar Bergen, J. Spencer Cornwall, and others, who received special citations for “faithful and meritorious service to their fellow men.” [10]

Individual Latter-day Saints increasingly gained prominence and thus were able to provide more support for Church activities. One example was Rose Marie Reid, who came to Los Angeles from western Canada in 1947. She became a noted designer and manufacturer of swimsuits. She frequently opened her beautiful Brentwood home for LDS social functions and became active in sharing the gospel with business associates and many others. [11]

Another noted individual who helped the Church during this period was the retired boxer Jack Dempsey. Although he had been baptized in his native Colorado, he did not participate actively in the Church after moving to California in the 1920s. Nevertheless, he was a “liberal contributor to the building of LDS chapels in California.” [12]

On 20 January 1950, Latter-day Saint artists of the Los Angeles area presented in the Wilshire Ward building what was designated the “First Annual Art Exhibition.” On display were 120 pieces from twenty-eight artists. “This was, in all likelihood the first art exhibit of the works of Mormon artists ever presented in California.” [13]

A widely publicized example of Latter-day Saint recognition occurred in 1951, when the brother-sister duo of Mel and Colleen Hutchins of Southern California’s Arcadia Ward achieved national fame. Colleen was crowned Miss America. Mel, playing for Brigham Young University, was named All-American and most valuable player in college basketball’s National Invitational Tournament.

Miss America Colleen Hutchins on Church magazine cover

Miss America Colleen Hutchins on Church magazine cover

Not only were individual members achieving recognition for their cultural attainments, but the Church as an organization was also sponsoring such activities. One example was the Mormon Choir of Southern California.

Wilshire Ward bishop Roy Utley inherited a tradition of outstanding ward choirs and went to unusual lengths to secure an accomplished director. Early in 1951, he contacted an acclaimed musician, H. Frederick Davis, a native of New Zealand then living in Whittier, about moving into the Wilshire Ward and directing the choir. Realtor Harold E. Phelps found a suitable home within the ward, and Davis moved to direct the choir.

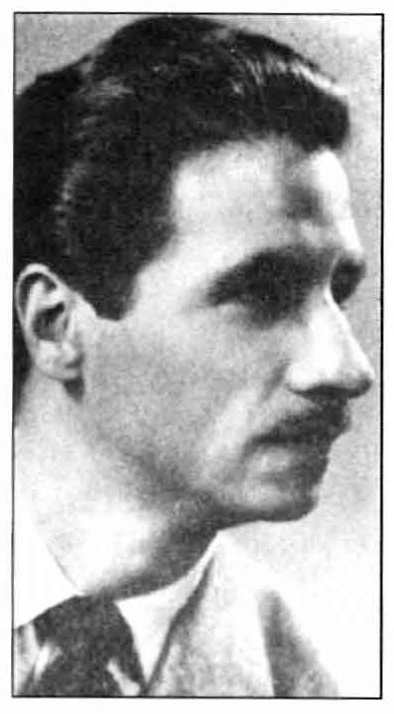

Choir conductor H. Frederick Davis

Choir conductor H. Frederick Davis

When officials at radio station KMPC were planning a program entitled “Go to Church,” they invited Davis and his choir to participate. The program’s producer was quite impressed and therefore wanted an expanded, three-hundred-voice choir, with Davis as director, for a special program at the outdoor Hollywood Bowl. When, with the advice of Los Angeles Stake president John M. Russon, Davis agreed to serve as director, the First Presidency gave approval to organize such a choir “on a one-time basis.”

A 309-voice choir was drawn from throughout the Los Angeles area. Following “a highly successful program” before an audience of eight thousand at the Bowl on 7 October, the choir was asked to perform again that same month at the San Bernardino centennial celebration. Following this concert, the choir was officially disbanded but was brought together once again to provide music for the famous Hollywood Bowl Easter sunrise service in April 1952.

The Hollywood Ministerial Association raised its voice in opposition “on the grounds that Mormons were not Christians.” However, when LDS representatives explained the Church’s faith in Jesus Christ, the objection was withdrawn. The choir made such a favorable impression that it was subsequently invited to sing in the churches of some of the very ministers who had initially objected. The choir was also invited to participate in NBC’s coast-to-coast radio program, “Faith in Action.” [14]

Owing to the widespread acclaim and repeated requests for appearances, stake presidents in the region enthusiastically recommended that the “Mormon Choir of Southern California” become a permanent institution. The First Presidency concurred.

In following years the choir became a symbol of excellence and made over one hundred national broadcasts and many appearances. It has sung for a United States president, at the dedication of the Los Angeles Temple, and at general conference in Salt Lake City. It presented George Frederick Handel’s Messiah at the opening of Los Angeles’s new music center in December 1964. [15]

In Northern California, a group of Latter-day Saint business and professional people residing in the Oakland Stake formed the Liahona Club. Its purpose was “the advancement of the cooperative and individual well-being of its members by bringing to their collective attention the respective abilities and business talents of all its members.” Just as the Liahona was a compass-like instrument used as a guide in the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi 16:10), so each club member was to be a guide or compass to his fellows.

Membership in the club was open to those who owned or operated their own businesses or were executives in private enterprise or government service. Through the years, the club undertook many projects. After the war it helped servicemen find employment. For a time, it sponsored Northern California’s LDS newspaper, the Messenger, and also constructed and maintained camps for Latter-day Saint youth. [16]

Church members also became involved in politics. On 5 October 1953 Latter-day Saint Goodwin J. Knight, California’s lieutenant governor, succeeded Governor Earl Warren, who was appointed to the United States Supreme Court. Knight thus became the second California governor with an LDS background. Born in Provo, Utah, and son of businessman Jesse Knight, he had come as an infant with his family to California in 1896. When they arrived, the Latter-day Saint population was just a few hundred. After graduating from Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, Knight went on to Stanford University—perhaps the earliest Latter-day Saint educated from elementary school to university completely in California. His name appeared in the first recorded minutes of the Los Angeles Branch Sunday School in 1915, though in his adult years he was not commonly identified as an active Church member. In 1954 he was elected by a wide margin as governor. His political career came to an end four years later, when he ran unsuccessfully for the United States Senate. [17]

Howard W. Hunter’s Ministry Continues

In 1946 Howard W. Hunter was released as bishop of the El Sereno Ward after six years of wartime service. A ward member later recalled: “As a bishop, he brought our small membership together in a united effort and taught us to accomplish goals that seemed beyond our reach. We worked together as a ward, we prayed together, played together, and worshipped together.” [18]

After his release, Brother Hunter continued to be involved in Church activities which were not as demanding on his time. With other high priests, one evening each week he visited church members at Los Angeles County General Hospital to give them blessings or help in other ways. Like most members of the period, he and his two sons spent many evenings and Saturdays working on a new ward meetinghouse. They put chicken wire on a wall of the chapel for plastering and installed acoustic tiles on the ceiling. The chicken-wired walls were later plastered by some inactive members who agreed to help. As a result, they once again became fully involved in Church activity.

Howard Hunter’s respite from heavy Church responsibility ended on 26 February 1950, when he was sustained as president of the Pasadena Stake. An important assignment came just over a month later during the April 1950 general conference in Salt Lake City, when he and the other Los Angeles stake presidents were summoned to the office of President Stephen L Richards of the First Presidency. President Richards explained that the time had come to consider a new early morning seminary program in California.

In earlier decades the Church had organized seminaries to provide religious education for high school students. In the LDS communities of the Intermountain West, such instruction had been offered as a regular part of students’ curriculum, but a different pattern was needed for areas where Latter-day Saints were more scattered and not dominant in the population. As early as 1941 the institute director in Los Angeles had reported that there were five high schools having more than one hundred LDS students each and that several others were approaching that number. However, wartime restrictions did not permit any new programs.

Now, at the 1950 meeting in President Richards’s office, Howard W. Hunter was appointed chairman of the committee to survey the various high schools in the area to see where such a program could be feasible. Following this evaluation, the eleven Los Angeles area stake presidents unanimously urged that early morning seminaries be started at once. [19]

This was no trivial undertaking. Formidable obstacles had to be overcome. Most classes had to serve more than one high school, each having a different schedule; hence, classes had to begin at 7 A.M. or even earlier. Also, carpools or other forms of transportation needed to be arranged. In September of that year, six pilot classes were inaugurated. Their success led to the addition of seven more that same school year.

Despite the difficulties of time and distance, 461 students flocked to these classes and registered an average attendance of 88 percent during that first year. Three years later, there were fifty-nine classes achieving an average attendance of 92 percent—a tribute to the devotion of students and parents willing to get up as early as 5:30 A.M. in order to attend or help children attend. [20]

Another Church program benefitted from President Hunter’s leadership. Soon after becoming stake president, he “was anxious to see a family home evening program developed which would be on the same evening in every home in the stake.” It was decided to set Monday evening aside. No other events would be held which would conflict with that “sacred evening.” [21] Fifteen years later, in 1965, a Churchwide “Family Home Evening” program was implemented, and in 1971 Monday night was set aside for this purpose. For many years, bumper stickers saying “Happiness is Family Home Evening” could be spotted on California automobiles.

The Church’s welfare plan also received attention during the postwar years. President George Albert Smith did not want to build up a huge, centralized system of storage and transportation, so urban stakes were encouraged to secure farm land on which they could raise locally the region’s necessary supplies of staples such as milk, meat, poultry, eggs, grain, fruits, and vegetables.

Less than four months after he became stake president, Howard W. Hunter received a telegram to meet with Henry D. Moyle of the First Presidency at a special Saturday meeting in Los Angeles. “We wondered what could cause such an emergency,” he recalled. It was the purchase of the 503-acre ranch from motion picture producer Louis B. Mayer, in Perris, about fifteen miles southeast of Riverside. The Church intended it to be used as a welfare project, producing farm crops, eggs, and poultry for the Los Angeles Region. President Moyle suggested that ten stake presidents formulate a plan whereby they could raise one hundred thousand dollars as a down payment and then set up a schedule to pay off the remaining $350,000 within five years.

The stake presidents conferred and proposed that they would work over the following six months to raise the necessary down payment. To their astonishment, President Moyle rejected the idea. “In his opinion, if we could not raise it in a month, it was a lost cause,” President Hunter remembered. “We talked it over again and decided to show him we could do it.” Each of the stake presidents immediately contributed his share and contacted his counselors and high council about the project. In turn, local bishops notified ward leaders and each added his contribution. By mid-afternoon Sunday, the money was collected and wired to Salt Lake City, where it arrived ahead of Elder Moyle. [22]

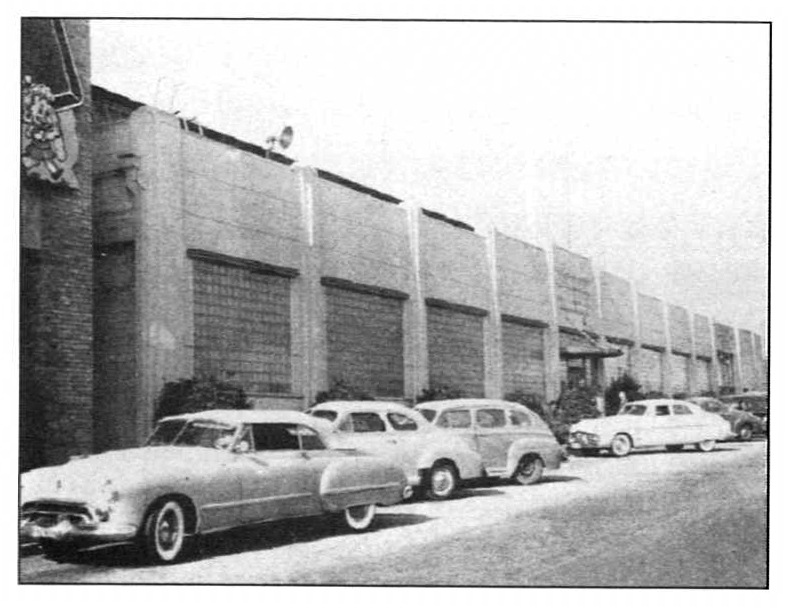

The ranch was formally dedicated by J. Reuben Clark, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, on 8 June 1951. The following day, the Church also dedicated an eighty-thousandsquare- foot industrial building on Soto Street in east Los Angeles which had been purchased the previous year for $175,000. This facility became the Southern California regional welfare center and served as the home base of the area’s Deseret Industries operation. A few years later it also housed the largest cannery owned by the Church. It processed orange juice, turkey, stews, chili, beans, tomatoes, and many other commodities grown on Southern California welfare farms. [23] The various Church welfare projects scattered throughout the area were coordinated by the Southern California welfare region, over which President Howard W. Hunter presided from 1952 to 1956.

Regional welfare center in Los Angeles

Regional welfare center in Los Angeles

Activities for Young People

During the postwar years the Church provided various activities for its youth. The first all-Church Softball tournament played its finals in Salt Lake City in the summer of 1949. Participating in the tournament were more than four hundred teams from all regions of the Church. The winner was the North Hollywood Ward from the San Fernando Valley. The following year another Southern California team, the Linda Vista Ward of the San Diego Stake, won the all-Church championship. [24]

The Church also involved the youth in cultural activities. For example, in the summer of 1954 the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Mutual Improvement Associations (MIA) held a conference in Southern California, patterned after the successful conferences held at Church headquarters each June. This was the first time such an event was ever held outside of Salt Lake City. “As chairman of the regional council of stake presidents,” Howard W. Hunter was the priesthood leader for this event. [25] In conjunction with this conference, some five thousand persons packed the East Los Angeles Junior College auditorium one Thursday night for two performances of a drama festival. Twenty thousand people were present as an orchestra and a chorus of fifteen hundred LDS youth filled the Hollywood Bowl for a Friday-evening concert and a Sunday afternoon special conference session. Another twenty thousand attended the Saturday-evening dance festival, which filled the playing field of the East Los Angeles Junior College football stadium with over four thousand brightly costumed youth intricately performing folk and modern dances.

A reporter for one of Los Angeles’s large daily newspapers remarked, “We have never seen anything like this before. You should tell the world about it.” Similar conferences and cultural festivals were held each of the following two years. [26]

A Memorable Era

The years following the close of World War II were memorable to specific groups of Latter-day Saints for various reasons. In 1945 the temple endowment was presented in Spanish at the Mesa Temple—the first time the endowment was available in a language other than English. About two hundred Spanish-speaking Saints gathered from California and other southwestern states. Most made sacrifices, traveling long distances to receive temple ordinances in their native tongue. Some came from as far away as Mexico City. Others lost jobs in order to attend. But, like earlier Latter-day Saint Pioneers, these endowed members were a substantial and committed base of Saints upon whom future growth was built. During succeeding years, the “Lamanite Conferences” and Spanish temple sessions at Mesa became eagerly anticipated annual events among these California Saints. [27]

For years, the president of the Spanish-American Mission, headquartered at El Paso, had supervised Spanish-speaking members and missionary work from California on the west to Louisiana on the east and from Denver on the north to the Mexican border on the south. In 1950, however, the territory of the mission was reduced to cover only Texas and New Mexico. With this change, California Spanish-speaking branches were placed under the jurisdiction of local stakes, thus ending the long isolation that had existed between the Spanish-speaking branches and overlapping English-speaking stakes and wards.

A major boost to the California Saints’ spiritual lives came when the 4 October 1953 session of the Church’s general conference in Salt Lake City was carried live on television to Los Angeles. Now members, in their own homes, could both see and hear their chosen prophets, seers, and revelators even as they spoke. This was a remarkable step forward that further unified Saints far removed from Church headquarters. Since that historic day, Saints throughout the Golden State have eagerly anticipated local television broadcasts of general conference and other Church programs. (Interestingly, television had been developed by a Latter-day Saint, Philo Farnsworth. In 1927 he built his first set in a San Francisco building on the corner of Green and Sansome Streets. He refined his invention while living in Southern California just prior to World War II.)

As the Saints were celebrating significant anniversaries and past achievements, they were also looking toward the future. The death of President George Albert Smith on 4 April 1951 touched the Saints with nostalgic sadness and in a sense marked the end of the memorable postwar era. At the same time, however, the California Saints crossed the threshold into a remarkable era of building and sacrifice which lifted the Church in the Golden State to a new plateau.

Notes

[1] Andrew Jenson, comp., “The California Mission,” 18 September 1847; LDS Church Archives.

[2] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:316.

[3] T. H. Watkins, California: An Illustrated History (Palo Alto, Calif.: American West, 1973), 359.

[4] Muir, 1:446.

[5] Ibid., 1:463.

[6] Church News, 31 January 1948, 1, 6–7.

[7] Muir, 1:459–60.

[8] Church News, 3 May 1958, 2; 5 July 1958, 7.

[9] Eugene E. Campbell, “A I listory of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952).

[10] Muir, 1:361–62.

[11] Ibid., 1:396.

[12] Ibid., 1:363–64; see also Jack Dempsey, Dempsey (New York: Harper and Row, 1977).

[13] Ibid., 1:478.

[14] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 207–9.

[15] Ibid., 208–9.

[16] Muir, 1:475.

[17] Dictionary of American Biography, Supplement 8, s.v. “Knight, Goodwin Jess (‘Goodie’).”

[18] Quoted in Eleanor Knowles, Howard W. Hunter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 101.

[19] Knowles, 131–32.

[20] William E. Berrctt, “A General History of Week-day Religious Education: The Seminaries and Institutes of Religion”; Church Educational System Archives.

[21] Knowles, 125.

[22] Ibid. ,125–26.

[23] Ibid., 133.

[24] Church News, 25 September 1949, 10-C; 30 August 1950, 8–9.

[25] Knowles, 133.

[26] Church News, 14 August 1954, 7; 2 July 1955, 1; 27 July 1956, 2.

[27] “Lamanite” refers to descendants of the people of ancient America described in the Book of Mormon.