A California Kaleidoscope: 1919–29

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 263–82.

The end of World War I brought a mood of celebration to the United States that lasted a decade. The “Roaring Twenties” were a time of heady optimism, nowhere felt with more fervor than in California. During this decade large numbers of Americans, including Latter-day Saints, sought to realize their dreams in the Golden State.

“The motion-picture industry . . . between the two wars did more than any other development to foster a yearning among the nation’s discontented to share in what California supposedly represented.” [1] As millions flocked to the neighborhood cinemas, they were infused with Hollywood’s portrayal of the “California Dream.” The Golden State had the traditional makings of dreams: fame, fortune, opportunity, adventure, climate, scenery, and a relaxed lifestyle. As more and more people purchased automobiles they were able to turn those fantasies into reality. A piece of the California lifestyle could be had by anyone with enough gas money to whisk him or her away to the Pacific shores.

California also had oil. As the northern part of the state had become rich on gold nearly a century earlier, the south now became rich on oil, triggering a boom which made California the nation’s leading oil producer for the next quarter century. A growing number of opulent mansions now overlooked the Pacific.

Taken together, these attractions were irresistible. During the 1920s, 1,900,000 out-of-state migrants entered, and of those, 1,368,000 settled in Southern California. It was the largest internal migration in the history of the United States, nearly ten times the size of the gold rush beginning in 1849 and the railroad land-boom of the 1880s.

Latter-day Saint Migration to California

As in the past, the nation’s mood was reflected among members of the Church. The number of California Latter-day Saints increased more than fivefold, from 3,967 in 1920 to 20,599 in 1930. Church members came to California particularly for advanced education, a mild climate, an interesting and stimulating culture, and the comparatively favorable salaries and working conditions. These magnets quickly gave the Church an energetic and enlightened membership, and out of this comparatively small group of about twenty thousand came a disproportionately large number of future business, political, Church, and other leaders, among whom was a future Church president, Howard W. Hunter.

These high achievers transformed a few home Sunday Schools and struggling branches into a kaleidoscope of new organizations, programs, and buildings. Meeting attendance and tithing payment rose. Church auxiliary organizations proliferated, Church leadership was strengthened, and new branches blossomed everywhere.

Presiding over this period of history was Heber J. Grant, who became Church president upon the death of Joseph F. Smith in 1918. A successful businessman, President Grant showed unusual talent and imagination in commercial affairs. His personal skills and his affiliation with the Democratic Party enabled him to mingle with prominent and influential people and in the process break down opposition and remove prejudice toward the Church. His warmth opened doors that had long been closed.

President Grant visited California repeatedly to establish goodwill and to manage the mushrooming growth. He seemed to recognize the potential that the Golden State held for the Church, and he had a special affinity for the California Saints.

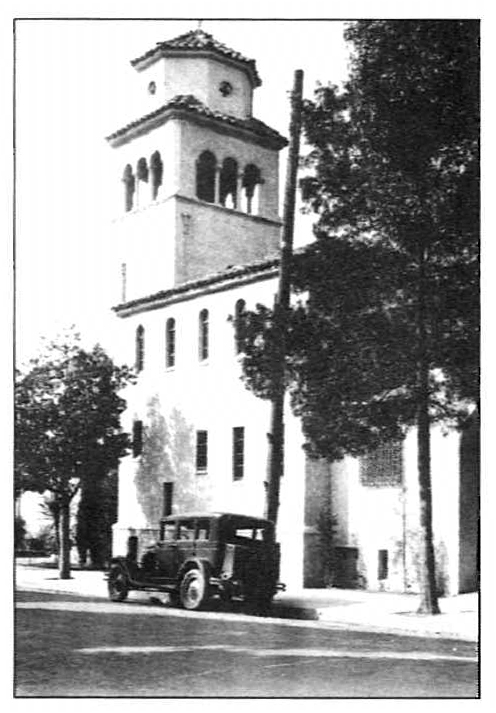

Heber J. Grant and Saints at Ocean Park chapel dedication

Heber J. Grant and Saints at Ocean Park chapel dedication

Despite the fact that the Church had encouraged growth and permanence outside the Intermountain area for thirty years, some still voiced concerns. In 1921 a group of Saints in Santa Monica, apparently responding to a rumor that the Church was again planning to call members back to Utah, wrote President Grant, asking if they were out of harmony with Church policy by living there. He answered their letter in person during one of his frequent visits to the Pacific Coast. He assured them that “at the present time the idea of a permanent Mormon settlement at Santa Monica was in full accordance with Church policies.” [2] He backed this up by handpicking such successful LDS business leaders as Joseph McMurrin, George McCune, LeGrand Richards, and others, and calling them to move to California where they could lead by example.

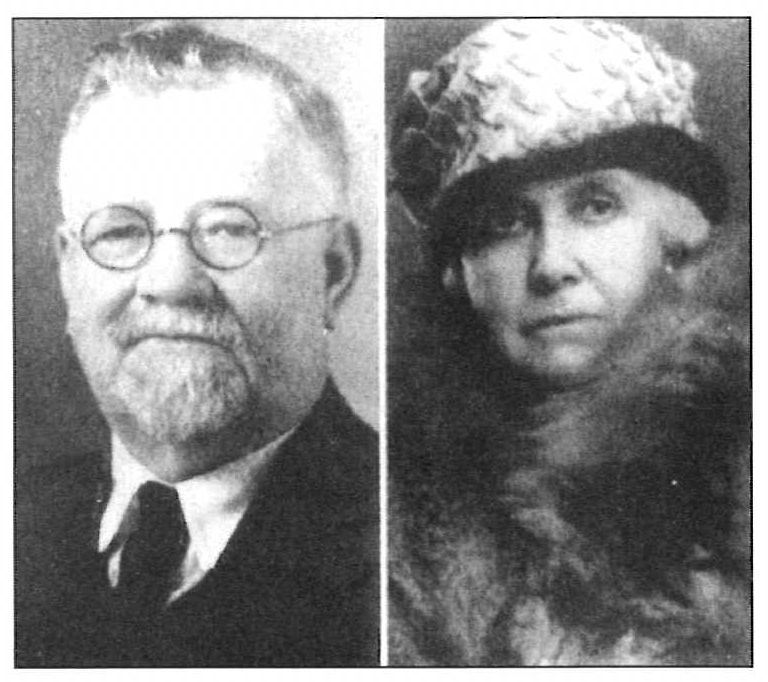

Mission president Joseph W. McMurrin and his wife Mary Ellen

Mission president Joseph W. McMurrin and his wife Mary Ellen

President Grant chose sixty-year-old Joseph W. McMurrin, a member of the First Council of the Seventy, to preside over the California Mission. Elder McMurrin became the second long-term mission president, holding his appointment from 1919 until 1932. When he came, he assumed the responsibility of nearly four thousand members scattered throughout little branches or Sunday Schools in California, Arizona, Nevada, and Oregon. He therefore endured a grueling travel schedule to interview potential leaders, provide personal counseling, approve building plans, issue temple recommends, and supervise missionaries. During his first year, branches were first organized in such widely divergent places as San Jose and Bakersfield. As a General Authority, he also spoke in general conferences in Salt Lake City twice each year. He was a man of profound faith, eloquent speech, and tireless devotion.

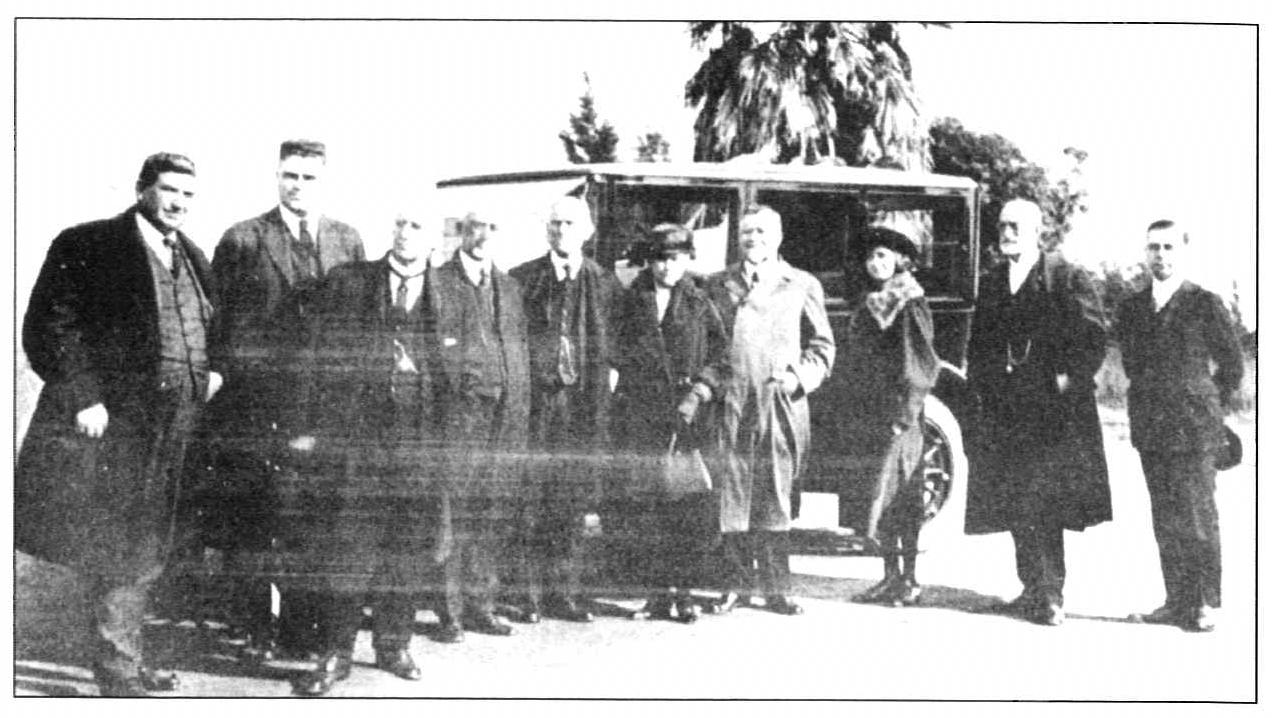

Harry Culver (right) offers temple site to president Heber J. Grant (next), with other leaders looking on; beginning third from left: Rudger Clawson (President of the Twelve), Charles W. Nibley (Presiding Bishop), Anthony W. Ivins (counselor in the First Presidency), and Sister and President McMurrin

President McMurrin was born in Tooele, Utah, in 1858 but soon went to Salt Lake City, where he lived until moving to California in 1919. By trade he was a teamster and stone cutter. He had worked on the Salt Lake Temple and had helped build dams and canals in northern Arizona.

In November 1885, after he was shot twice through the abdomen by a United States deputy marshal on a polygamy raid, doctors despaired of his life. In a visit to his bedside, Elder John Henry Smith asked him if he desired to live. McMurrin affirmed his strong desire to live and enjoy the company of his wife and two children. Elder Smith then promised him he would live. His recovery was regarded as miraculous.

Temple Sites Considered

Since Brigham Young had mentioned that “in process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord,” [3] there had been talk of a California temple. While the early Church had not been strong enough to warrant the construction of one of those sacred structures in California, the many talented and faithful Latter-day Saints now coming made thoughts of a temple more plausible.

In 1921 Harry Culver, a non-LDS Los Angeles real estate developer and founder of Culver City, offered to give the Church a six-acre tract in Ocean Heights plus a contribution of fifty thousand dollars if it would build a five-hundred thousand- dollar temple there. In December of that year, President Heber J. Grant and other General Authorities traveled to Los Angeles to inspect the property. At first Church leaders were favorably impressed, but they eventually declined the offer because of financial commitments to complete temples already in progress in Arizona and Alberta, Canada. “It might also have been said,” one Church leader added, “that temples are not built to further real estate schemes or enterprises; temple locations and temple buildings stand apart from all such considerations.” [4] Despite this disappointment, Southern California Saints continued to cherish the thought that a local temple would one day grace their area.

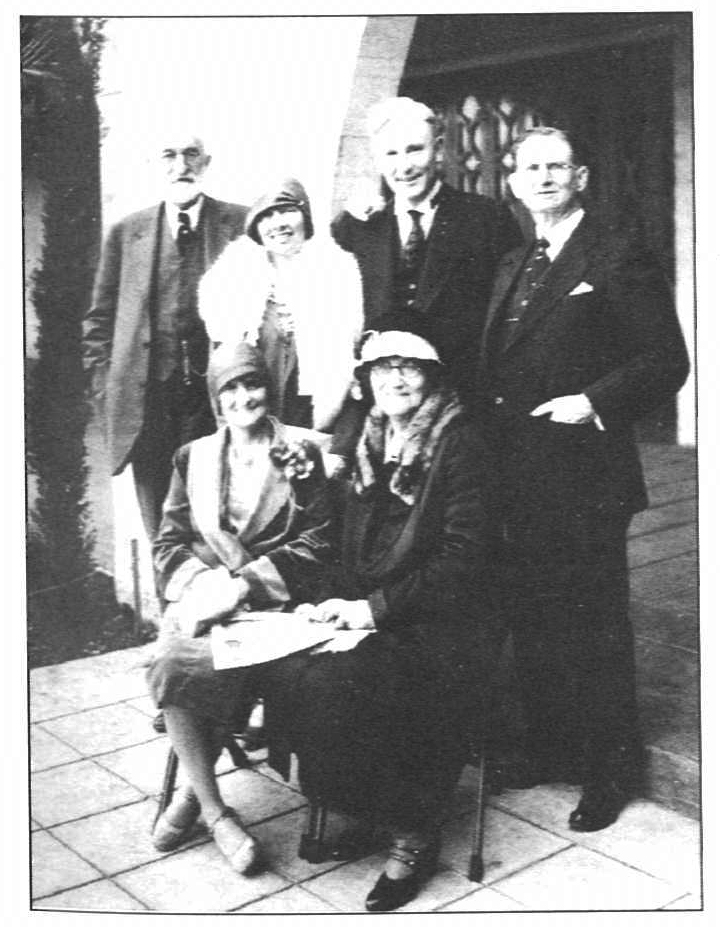

President Heber J. Grant, Willshire Ward bishop David Howells, and Hollywood Stake

President Heber J. Grant, Willshire Ward bishop David Howells, and Hollywood Stake

President George McCune with their wives in front of the stake center

The Saints in Northern California also began speaking of prophecies concerning a temple in their area. During the summer of 1924, Elder George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve was in San Francisco attending regional Boy Scout meetings. On that occasion he met with W. Aird Macdonald, president of the Church’s small branch across the Bay in Oakland. They met at the Fairmont Hotel high atop San Francisco’s Nob Hill. President Macdonald, a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, later reported his memory of the occasion:

From the Fairmont terrace we had a wonderful panorama of the great San Francisco Bay nestling at our feet. The setting sun seemed to set the whole eastern shore afire, until the Oakland hills were ablaze with golden light. As we admired the beauty and majesty of the scene, President Smith suddenly grew silent, ceased talking, and for several minutes gazed intently toward the East Bay hills. “Brother Macdonald, I can almost see in vision a white temple of the Lord high upon those hills,” he exclaimed rapturously, “an ensign to all the world travelers as they sail through the Golden Gate into this wonderful harbor.” Then he studied the vista for a few moments as if to make sure of the scene before him. “Yes, sir, a great white temple of the Lord,” he confided with calm assurance, “will grace those hills, a glorious ensign to the nations, to welcome our Father’s children as they visit this great city.” [5]

But the Saints in both Northern and Southern California would have to wait more than thirty years for their temple dreams to become a reality.

The First California Stakes

Church growth in California occurred in a logical sequence. In areas where Latter-day Saint population was sparse, small Sunday Schools were established—often meeting in members’ homes. Those were supervised and often staffed by the nearest fully organized branch. As these Sunday Schools grew, they eventually became independent branches. When branches within a given district reached a sufficient size and necessary leadership could be supplied from within the area, they were reorganized as wards and grouped into a stake. The creation of wards and stakes not only provided members with solid local support, but it also alleviated the mission president’s responsibility to oversee the day-to-day operation of these individual units.

Church growth was so great and President McMurrin’s schedule so heavy that it became apparent that either the mission had to be divided or self-administered stakes organized to relieve part of the load. But were the California members ready to stand on their own? In the three years after President McMurrin’s appointment as mission president, membership in Los Angeles more than doubled. As opposed to just three small branches in this area when he came in 1919, eleven thriving branches were now meeting in Los Angeles, Long Beach, Ocean Park, Garvanza, Boyle Heights, Hollywood, Glendale, Alhambra, Inglewood, Huntington Park and San Pedro. Five small groups met in Lankershim, Pasadena, Redondo, Belvedere Gardens and Home Gardens.

After his appointment, President McMurrin carefully trained members to take over the leadership in Southern California. He realized early that the creation of locally administered congregations “would make the members more independent and self-reliant” and would free him to concentrate his efforts on preaching the Church’s message to non-Latter-day Saints. [6]

Early in 1922, he sent his recommendation to Church headquarters that a stake be organized in Los Angeles. The recommendation was approved. In April, President Grant went to New York City where he visited with George W. McCune, who indicated his intention to make his home in California when released as president of the Eastern States Mission. President Grant asked him to accept the presidency of the proposed stake. The invitation was accepted, so McCune, his wife, three sons, and one daughter established their home in Los Angeles on 4 September 1922, four months before the stake was organized.

Born in Nephi, Utah, President McCune was an Ogden businessman and financier prior to his call to the eastern states. As he became acquainted with the people over whom he would preside, he could not help but notice the differences among the Saints since he had last visited the area three years earlier. While the members in Los Angeles had been faithful in 1919, he found them even more so in 1922. In fact he was “astonished . . . at the wonderful devotion and interest shown by our people in the gospel of our Redeemer in that portion of the vineyard.” He attended a Sunday School at Ocean Park which was so crowded that twenty-five children had to stand. “On the same day,” he continued, “I attended the services at Los Angeles; and when I left that place a little over three years ago, their [Adams Boulevard] chapel was ample to accommodate them all. When I returned I found that little chapel was wholly inadequate for the Sunday night meeting, and every available space was taken for standing room.” [7]

While in California, President McCune continued to nurture business interests as a real estate developer and as one of the original organizers of the Bank of America, of which he was director for many years.

In the early autumn of 1922, the announcement was made by the First Presidency that a stake was to be established in Los Angeles. When the time for the organization arrived, President Heber J. Grant personally directed the proceedings, beginning with a meeting of Church and local officers on Friday afternoon, 19 January 1923. Accompanying him were Charles W. Penrose, a counselor in the First Presidency, George Albert Smith, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve, and Charles W. Nibley, Presiding Bishop. Also assisting and counseling in the matter was President McMurrin. In the meeting, the appointment of President McCune was announced, and Leo J. Muir and George F. Harding were chosen as his counselors. The following day consideration was given to the membership of the high council and to the leaders of auxiliary organizations.

The organization of the Los Angeles Stake on 21 January 1923 was an auspicious occasion, as it marked a new precedent, not only for California but for the entire Church. Not only was California the first state outside of the Intermountain territory to have a stake, but Los Angeles was the first major urban setting for one outside of Salt Lake City. And for the first time, Church jurisdiction in California was split. Nearly four thousand stake members were now shepherded by President McCune, while members outside of stake boundaries were presided over by the mission president, Joseph W. McMurrin.

With the stake organization in place, attention was given to organizing its constituent wards. The first ward in modern California was organized on 11 March 1923, when the original Los Angeles Branch became the Adams Ward, a month and a half following the organization of the stake. Under the direction of President Grant, Hans Benjamin Nielsen was sustained as bishop of the ward with Ezra Taft Benson (a cousin of the future thirteenth Church president) and Basil T. Kerr as counselors. Other wards organized that year included Alhambra, Belvedere, Boyle Heights, Florence (later renamed Matthews in honor of a member who contributed generously to the building fund), Garvanza, Glendale, Hollywood, Huntington Park, Tnglewood, Long Beach, Ocean Park, and San Pedro. [8] Signs of prejudice against the LDS people seemed to have vanished, and there was therefore little difficulty in acquiring suitable meeting places.

It was now up to the new stake to show what it could do. Attention turned to developing an efficient organization. This was a challenge, because some of the stake officers had not known each other beforehand, and many members were not familiar with stake or ward procedures. The “success formula” for this new organization embodied the cultivation of three lofty traits: a cooperative spirit, a “high standards attitude,” and a habit of achieving. One member of the stake presidency later recalled that these goals stimulated both leaders and members: “Enthusiasm was wide-spread and spontaneous. Everybody seemed to rally to the challenge.” The new stake quickly stepped to the forefront of the Church with high percentages in attendance of meetings and “ward teaching” visits to families in their homes. [9]

In just four years the stake’s membership doubled. The administrative load was again too burdensome for one presidency. An assignment to divide the stake came to apostles David O. McKay and Stephen L Richards. Under their direction, details were worked out in a meeting held in the basement of the Adams Ward chapel. They also decided to divide the Adams Ward at Vermont Avenue, the western portion becoming the new Wilshire Ward. At the stake conference held on 21 and 22 May 1927, the more northerly wards became the Hollywood Stake (later renamed Los Angeles), with George W. McCune as president. The southern portion, with Leo J. Muir as president, retained the name of the Los Angeles Stake (later renamed South Los Angeles). [10]

Leo J. Muir was a Utah educator and town mayor before coming to California in 1922 to begin a new career in finance. He served a combined sixteen years as counselor and then president of the first modern stake in California. He was thus an important historical figure who later wrote a nostalgic eyewitness account of the Church’s growth and development during the period. [11]

With the success of the stake in Southern California, Church leaders felt ready to create a similar unit in the north. By 1926 there were fifteen hundred members in the San Francisco area; hence local leaders wrote to mission president McMurrin urging that a stake be organized. At a conference on 10 July 1927, apostles Rudger Clawson and George Albert Smith proposed to organize a San Francisco stake. The visitors explained that the Saints “could have a stake here if they wanted it, but if they did not want it they did not need to,” and that they could not proceed without knowing the feelings of the members. The congregation unanimously opted to become a stake. President McMurrin said that “the time is not far distant when there will be five new stakes in this state and the organization will continue until the entire state is organized.” [12]

Oakland Branch president W. Aird Macdonald was called to preside over the new stake with J. Edward Johnson and Clyde W. Lindsay as his counselors. The new stake consisted of the Berkeley, Daly City, Dimond, Elmhurst, Martinez, Mission, Oakland, Richmond, San Francisco, and Sunset Wards, and a few branches.

President Macdonald, a native of Arizona, had resided in the Bay Area since 1911. He was an artist, writer, and photographer for local newspapers. In later years, he became an insurance agent and a member of both the California State Board of Equalization and the prestigious Commonwealth Club.

The stake was the ninety-ninth organized in the Church, with a membership of over three thousand—mostly “day (laborers), a few professionals, a school teacher here and there, and a lawyer or two in the Oakland Branch.” [13]

Church Buildings

The Latter-day Saints in California had few permanent meeting houses. Worshiping or attending Church activities in rented halls—fraternal lodges, public auditoriums, other churches, schools, and almost every other imaginable place, including a room above a fire station at Barstow and an abandoned jail in Whittier—was an almost universal experience for pioneering members in small branches. In rented halls, it was common to sweep up cigarette butts which remained from Saturday night activities, or to detect the pungent odor of stale cigarette smoke or alcohol during sacrament services.

Typical was an experience in the Bay Area’s Martinez Branch, which held services in a rented lodge hall. After Sunday School, having received word that the stake presidency would be attending their sacrament service that evening, the members carefully prepared the hall. When the Saints and stake visitors arrived a few hours later just prior to sacrament meeting, “the hall was in complete disarray. A Portuguese wedding had been held there between services and the hall was left in disorder and reeking of spilled wine and tobacco smoke.” [14]

Therefore, a challenge facing stake and mission leaders was to provide adequate meeting places for the increasing number of congregations. In 1925, for example, mission president Joseph W. McMurrin reported that he had dedicated new chapels at Santa Anna, Modesto, and Sacramento and that the two branches in San Francisco had jointly built an “amusement hall.” He planned to purchase an existing building in Bakersfield and to build another “amusement hall” in San Diego. [15]

In Southern California there were only three chapels capable of accommodating wards of six hundred to one thousand people—Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Ocean Park. The fact that other wards met in rented halls generally precluded a full complement of Church activities, particularly for the youth. It was therefore with anticipation that members in the two Los Angeles stakes began planning their own buildings.

In the 1920s, local Saints raised approximately half the building costs, with general church funds providing the other half. The two stakes began raising funds for a stake center they could share. A newly formed inter stake building committee conducted its first meeting in February 1927 while parked “in an automobile in front of Adams Ward Chapel.” In less than two months, $110,263 “had been pledged to the fund.” [16] However, the First Presidency directed that two buildings be built. Accordingly, the fund was split between the two stakes, and each began plans for its own stake center.

Ten months after the committee first met, the Los Angeles Stake, having raised sufficient funds, received final approval to begin construction—a prodigious feat given President Grant’s insistence that all Church lands and buildings be procured and built without mortgages. Five months later the “Tabernacle,” a large stake center completely furnished and equipped, was opened in Huntington Park.

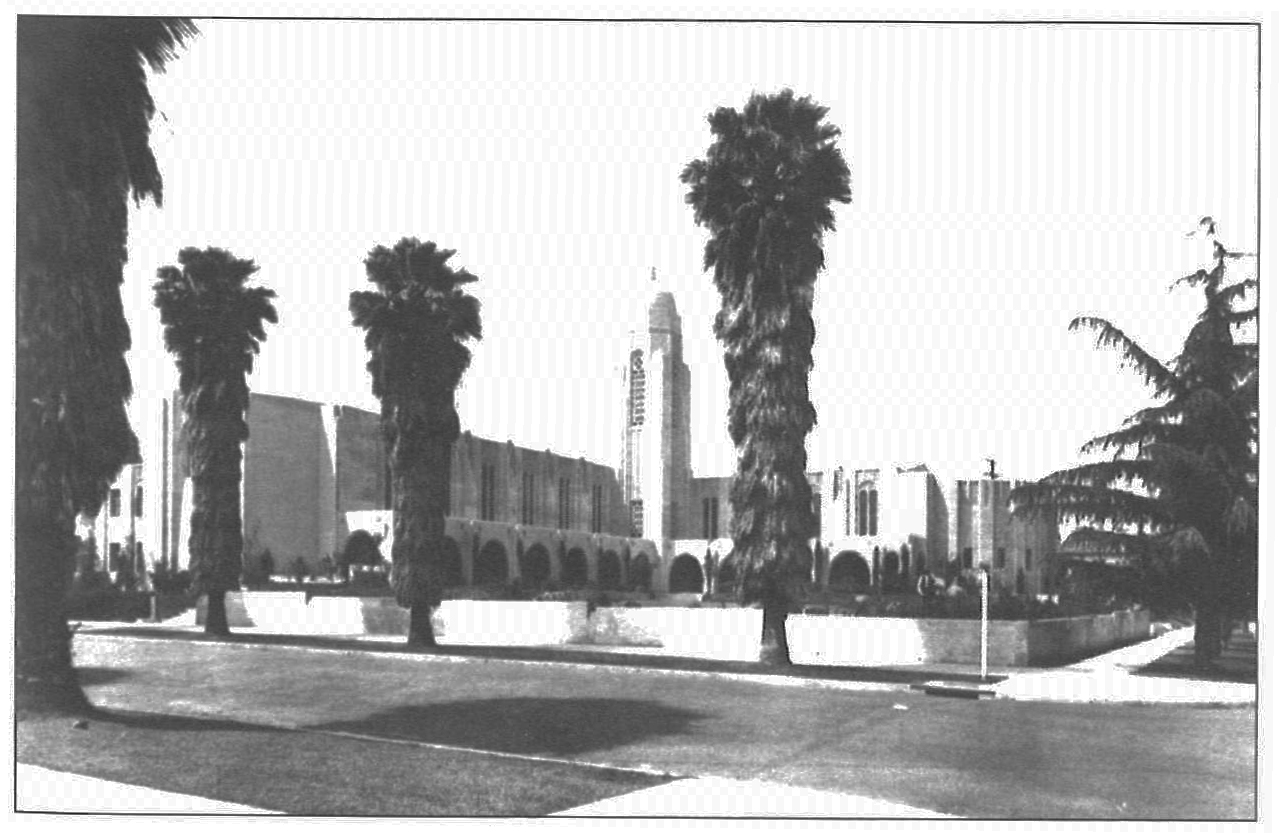

Stake center in Huntington Park

Stake center in Huntington Park

The Hollywood Stake began building its own stake center, also known as the Wilshire Ward chapel, on 15 April 1928, when the cornerstone was laid by President McCune in a grand ceremony. Stake members not only donated and collected enough money to keep the $250,000 project out of debt, but they also donated countless hours in construction labor. Generally, the men did the heavy construction, while the women did the painting and interior decorating. Once, while visiting the area, President Heber J. Grant “picked up a shovel” and “did his part that day in landscaping.” [17] When it was completed in April 1929, two members of the First Presidency came from Salt Lake City for its dedication.

Willshire Ward chapel

Willshire Ward chapel

President Heber J. Grant declared that other than the temples and the Salt Lake Tabernacle, it was the finest building in the Church. It remained California’s most imposing LDS structure for the next thirty years, until the construction of the Los Angeles Temple. The building was admired by non-Latterday Saints as well, being named the “finest cement building in America” by Architectural Concrete in 1933. [18] Today it remains a notable example of California’s art deco architecture and is a Los Angeles landmark.

Over the next several years, Church buildings multiplied, helped considerably by Swiss architect Louis Thomas, who came to Los Angeles in 1921 and began a notable career, designing over twenty LDS chapels throughout Southern California. Many others were on the drawing board or under construction in other places. As the state and nation prospered, so did the Church.

Varied Activities and “Firsts”

The scope of Latter-day Saint activity in California could be seen in the wide variety of programs instituted by the California Mission and its branches and by the newly organized stakes and their wards. The following are some of the programs which took root during that period. [19]

The Relief Society was particularly active. Following the lead of the general Church, California Relief Societies became involved in local social service agencies and maternity hospitals. When a child guidance clinic was established in Los Angeles, the stake Relief Society became a charter member. This involvement brought local LDS women leaders into active participation in many of the social welfare programs of the city, county, and state. A social welfare convention was held in the Adams Ward chapel in 1924 in which eminent social workers in Southern California participated. The stake Relief Society also contributed generously to the children’s hospital and to a home for girls in Los Angeles.

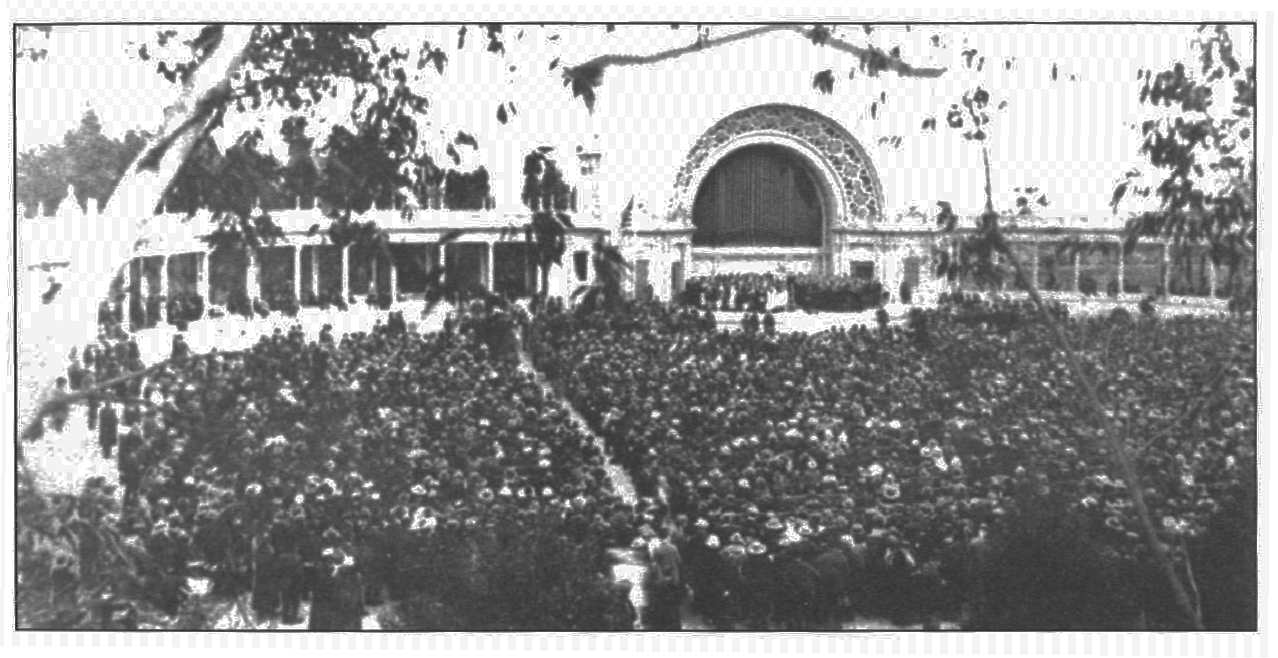

Other activities or “firsts” included the following: Ada Gygi Hackel’s earliest Primary for children in Los Angeles was conducted in her home at 208 East Santa Barbara Street in 1919; the Ocean Park Branch Dramatic Club presented a three-act drama in the Women’s Club at Santa Monica on 19 February 1921; a Sunday School conference met at the Adams chapel on 25 September 1921; and in 1922 the choir of the Los Angeles Conference of the California Mission presented Evan Stevens’s cantata, “The Vision,” to an audience of twelve thousand people in Balboa Park, San Diego.

Los Angeles choir at San Diego's Balboa Park

Los Angeles choir at San Diego's Balboa Park

In the autumn of 1922, Los Angeles “M Men” (young single adults) elected Jay S. Grant as their first district president. In December 1923 Wallace E. Lund of the Belvedere Ward organized the first Latter-day Saint Boy Scout troop in Southern California.

In February 1924 the first directory of stake and ward members in Southern California was published by the M Investment Company—a group of young LDS men who had gone into business together. During that same year Alma B. Summerhays launched the first Latter-day Saint news publication in Southern California—the Los Angeles Stake Journal—a monthly eight-page paper, eight by ten inches in size. This publication carried on for a year or two with fair success. A young men’s basketball league was also organized in 1924. The Matthews Ward won the first league championship.

The first Old Folks Committee was organized on 25 March 1925. On 1 May of the same year, a genealogical conference in California convened at the Adams chapel.

Latter-day Saints were also active in commemorating their heritage. The first California chapter of the Daughters of Utah Pioneers was founded at Los Angeles in February 1927. Latterday Saints were honored on 31 May of that year when a new San Bernardino County courthouse was dedicated on the lots where the original home of Amasa M. Lyman had stood. The following day at Sycamore Grove, a concrete, steel, and bronze monument was unveiled and dedicated to the memory of the Saints who had camped there for several weeks while negotiating the purchase of the Rancho where they founded San Bernardino. [20]

Other “firsts” during the 1920s included the commencement of missionary work among California’s Spanish-speaking population and the beginnings of religious programs for college students. Both of these efforts would see significant development during the following decade.

On 8 September 1929, at the invitation of the stake presidency, the Honorable John C. Porter, mayor of Los Angeles, addressed the morning session of the Los Angeles stake conference—probably the first public official to address an LDS stake conference in California. Mayor Porter stressed the need for a religious and moral crusade in the city of Los Angeles.

Later that year, on 6 October 1929, Rachel Latham and Irmgard Kreipl Koening of the Los Angeles Stake were among the first women set apart as stake missionaries.

This period of California Church history ended abruptly with the stock market crash in the fall of 1929. Just over two years later, seventy-three-year-old Joseph W. McMurrin was honorably released as mission president because of ill health. He died in Los Angeles on 24 October 1932 and was buried in Forest Lawn Memorial Park. During his twelve-year administration, he witnessed the most remarkable changes in the Church since the gold rush days.

At the beginning of his administration, he presided over all Church members in California and parts of three other states; but when he was released, fifteen thousand members in California’s two largest population centers were under local stake leadership. New and beautiful buildings were in place, and the degree of Church activity had risen to new heights. The Church was now firmly and permanently rooted in California soil—a position from which it would grow, as President McMurrin had prophesied, until stakes would blanket the entire state.

Notes

[1] David Lavender, California: A Bicentennial History (New York: W. W. Norton, 1976), 175.

[2] Andrew Jenson, comp., “The California Mission,” 29 October 1921; LDS

[3] Journal History, 7 August 1847; LDS Church Archives.

[4] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 6:493.

[5] Harold W. Burton and W. Aird Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” Improvement Era 67, no. 5 (May 1964): 380.

[6] Eugene E. Campbell, “A History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in California, 1846–1946” (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1952), 347.

[7] In Conference Report, October 1922, 152.

[8] Campbell, 351.

[9] Leo J. Muir, A Century of Mormon Activities in California (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1952), 1:153–54.

[10] Ibid., 1:155.

[11] Ibid., vols. 1 and 2.

[12] Harold R. Jensen, interviewed by J. Edward Johnson, 15 May 1935, Oakland Stake Collection.

[13] Leon Baer, Oral History, 5; James Moyle Oral History Archives, LDS Church Archives.

[14] Evelyn Candland, An Ensign to the Nations: History of the Oakland Stake (Oakland: Oakland Stake, 1992), 28.’

[15] Mission Annual Reports, 1925, 64; LDS Church Archives.

[16] Muir, 1:154.

[17] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 86.

[18] Ibid., 84–91.

[19] For a more detailed account of these activities, see Muir, vol. 1.

[20] Muir, 1:460.