California Beginnings: 1846

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 41–58.

The year 1846 was the beginning for both modern-day California and Latter-day Saint settlement in the West. For the first time, California attracted more settlers than Oregon. After the year began, thoughts of Latter-day Saint immigration brought concerns to California residents who feared they might be forced to capitulate to a unique group of new arrivals.

Thomas O. Larkin, the United States consul at Monterey, received word from a correspondent at the New York Sun that the Saints intended “to have a body of 100,000 persons” in California by spring. [1] Apparently, someone had added an extra zero to Brigham Young’s letter to Brannan that requested ten thousand Church members in “St. Francisco.” Latter-day Saint membership in the Golden State did not reach this level for over a century.

Another correspondent gave a more realistic figure when he wrote that there were “about 10,000 Mormons ready to start for California & that they will reach out 25 miles with their waggons etc. Look out for an avalanch.” He also warned Larkin to “settle all your affairs promptly next spring. You will have all the Mormonry among you, who will act towards you as the Israelites did to the nations among whom they came, kill you all off & take possession of your worldly gear.” [2]

Such reports, though unfounded, upset even the native Mexican “Californios.” The French consul at Monterey reported that the Mexicans had “a terrible fear” of the Saints, and were ready “to give themselves up” to anyone who would “deliver them from this plague.” [3] Even Mexican governor Pio Pico was concerned about the approaching “Mormonitas,” who claimed California as their “promised land.” [4] On 6 March 1846, Consul Larkin reported that news of the approaching Saints had “caused some excitement and fear among the natives.” [5]

Eastern Pilgrims

Though California’s population was sparse, the Brooklyn Saints did not exactly arrive in a vacuum. In fact, it is possible that a few Latter-day Saints may have reached California even before Brannan and the Brooklyn colony. A group of immigrants arriving in 1845 was led by William Brown Ide, who had participated in the “Bear Flag Revolt” a month before the Brooklyn arrived. A year before, Ide had been a delegate to a convention in Illinois which had named Joseph Smith as a candidate for United States president. Hence he is presumed to have been LDS, though he later denied it. His group of some fifty men and families perhaps included other Latter-day Saints, but there is no conclusive evidence.

In any case, the Latter-day Saints proved to be more benign than anticipated. There are few if any accounts of troubles between the Brooklyn Saints and their neighbors. They also established an early American tone of faith and sobriety that, although short-lived, can still be looked upon with a certain satisfaction.

Just as the eastern coast of the United States was settled by religious Pilgrims, so it was with the western coast. Both coasts were initially claimed by people who came in the name of religion: New England by Protestant Pilgrims, and California by Roman Catholic Franciscans, who rather than conquering or banishing the natives established instead a chain of missions to educate them and teach them Christianity. Now Latter-day Saints, religious heirs of New England Pilgrim and Puritan stock, began to transplant their religious ideals from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific coast. New England values and institutions began replacing Native American, Mexican, and Roman Catholic counterparts.

On 14 June 1846, just six weeks before the arrival of the Brooklyn, a small group of Yankee settlers raised their “bear flag” in revolt against Mexican rule. On 7 July, Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, raised the U.S. flag over the customs house at Monterey. And on 9 July, Capt. John B. Montgomery of the U.S. sloop Portsmouth raised the American flag at the plaza in Yerba Buena. Yet, it was the Brooklyn which, on 31 July, brought an adequate number to implant firmly and permanently, without armed conflict, the Yankee way of life. In fact, by the end of 1846, a majority of the American settlers in California were eastern-bred Latter-day Saints. It has been said that of all the cities in the West, San Francisco is most like those of the East. Those early pioneers made it so from its earliest American beginnings.

“Thus,” California’s eminent historian Hubert H. Bancroft writes, “San Francisco became for a time very largely a Mormon town. All bear witness to the orderly and moral conduct of the saints, both on land and sea. They were honest and industrious citizens, even if clannish and peculiar.” [6]

California’s first newspaper, the Californian, in its initial edition published in Monterey on 15 August 1846, described the recently arrived Latter-day Saints as a “plain industrious people.” [7]

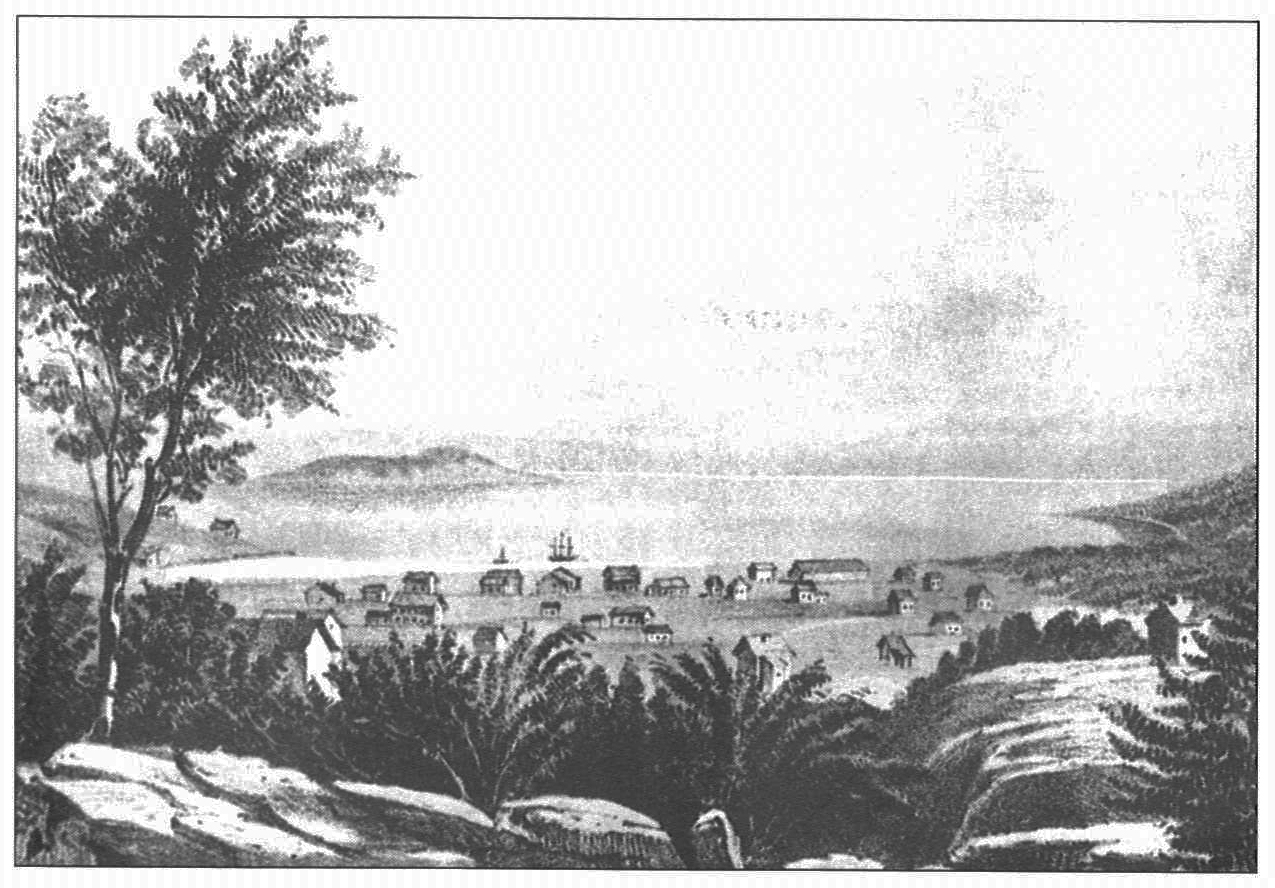

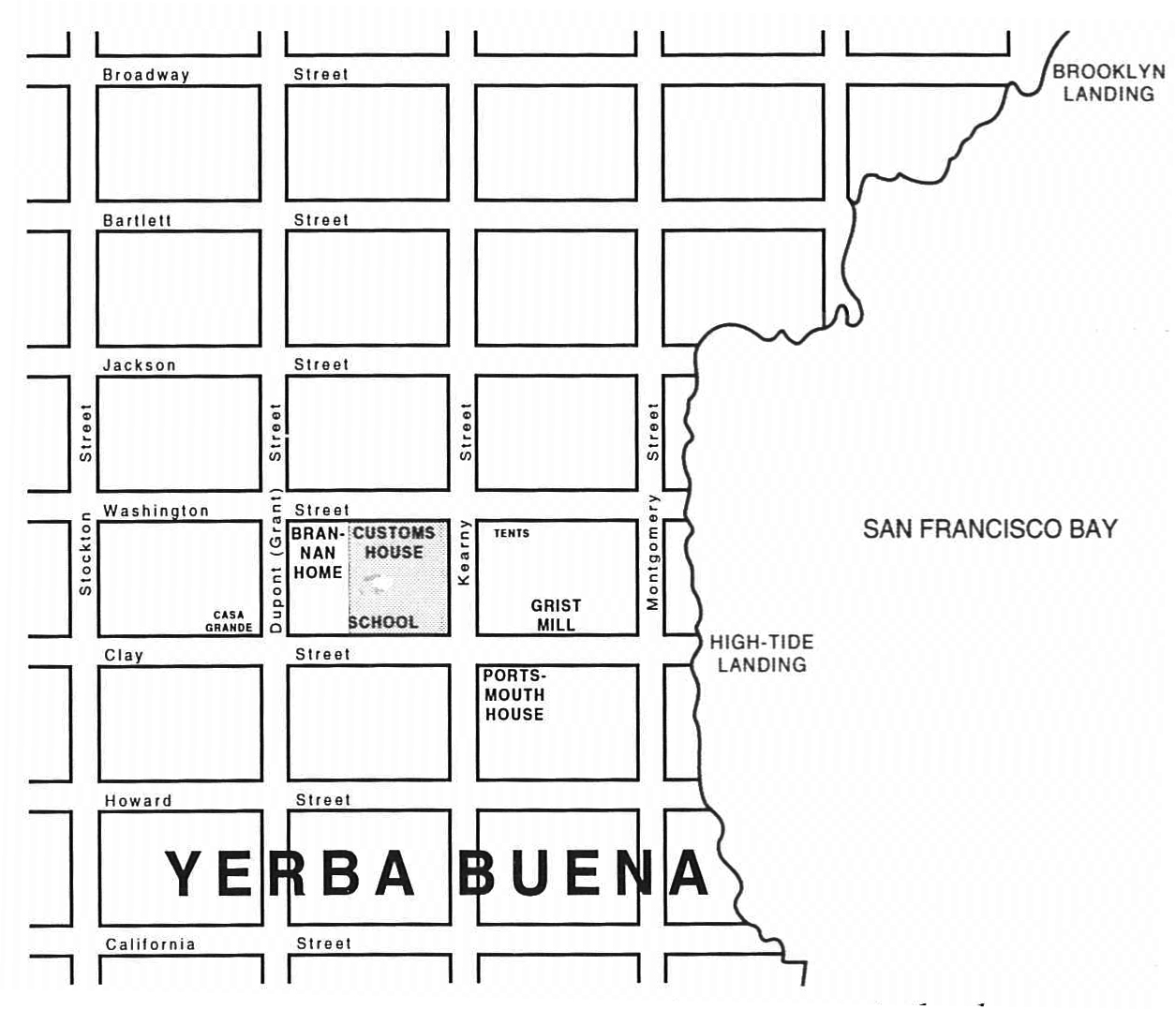

Although the Brooklyn group was young—the median age was around twenty with only eleven over fifty—many among them had varied skills; there were doctors, teachers, editors, mechanics, carpenters, farmers, and millers. The degree to which their industry and talents helped develop the new town and maintain cordial relations confirms that they were a boon to California. When they arrived, Yerba Buena consisted of only about thirty buildings, including nine adobe dwellings scattered over the clear space that stretched back from the beach. There were several Mexican families, a half-dozenAmericans, and about one hundred Indians, as well as the officers and men of the Portsmouth.

Getting Established in Yerba Buena

1846 view of Yerba Buena

1846 view of Yerba Buena

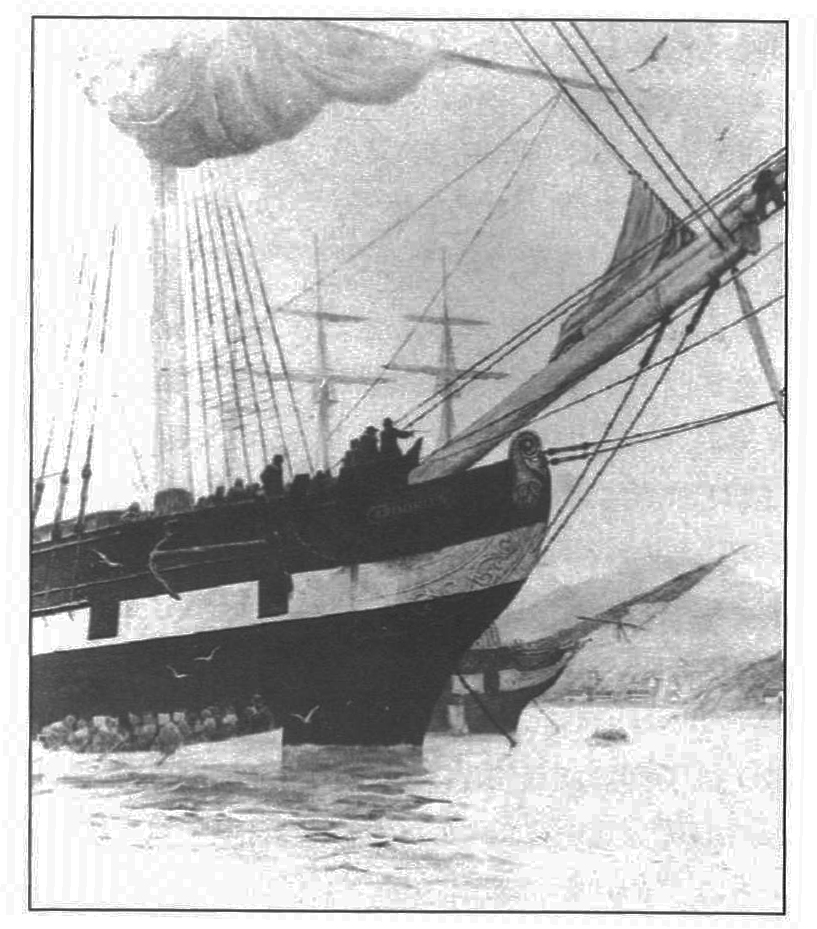

Immediately after the Brooklyn was boarded by sailors from Captain Montgomery’s ship, Brannan and his two counselors were taken to the captain to explain their presence. Montgomery gave his permission for the Saints to land and disembark. Several men then went ashore on one of the Brooklyn’s shore boats, at what eventually became the foot of Clay Street, a high-tide landing spot.

The next day, Saturday, other passengers began disembarking. The tide was high enough until midmorning for continued landings, and soon the beach was strewn with baggage of every description—crates of chickens, what was left of the forty pigs, and the two milk cows. As the tide went out, the boats changed their landing place to the foot of a rocky bluff—later named Clark’s Point—below the peak of Loma Alta, which eventually became San Francisco’s famous Telegraph Hill.

“The ship Brooklyn left us on the rocks at the foot of what is now Broadway,” wrote Carolyn Joyce Jackson. “From this point we directed our steps to the old adobe [the postmaster’s “Casa Grande”] on . . . Dupont [now Grant] Street. It was the first to shelter us from the chilling winds. A little further on (toward Jackson Street), stood the adobe of old ‘English Jack,’ who kept a sort of depot for the milk woman, who came in daily, with a dozen bottles of milk hung to an old horse.” [8]

Brooklyn saints preparing to disembark

Brooklyn saints preparing to disembark

The following day was Sunday, normally a day of rest and worship for the sailors in port. Captain Montgomery invited the Saints to attend religious services on board his ship. One of the Portsmouth’s sailors recalled, “Anxiety to see and examine the female portion of this strangesect, was apparent on the faces of all.” The sailors set up chairs under an awning on the quarter deck and eagerly awaited their guests’ arrival. The crew’s curiosity was heightened by rumors that Mormons were a strange class of people who grew horns. As the visitors came on board “curiosity appeared to fade away” and one sailor muttered, “D—nation, why they are just like other women.” There was no chaplain, but it was Montgomery’s custom to read a printed Episcopalian sermon to his men. After the service the Saints lunched with the captain, were escorted on a tour of the vessel, and then left for their own ship, “having created a most favorable impression among the hardy Tars of the good ship Portsmouth.” [9]

On Monday morning, Montgomery directed his men to help unload the Brooklyn. One of his men left a written account: “The cargo of the Brooklyn consisted of the most heterogeneous mass of material ever crowded together; in fact, it seemed as if, like the ark of Noah, it contained a representative for every mortal thing the mind of man had ever conceived. Agricultural, mechanical and manufacturing tools were in profuse abundance; dry goods, groceries, and hardware, were dug out from the lower depths of the hold, and speedily transferred on shore, our men working with a will which showed the good feeling they bore for the parties to whom they belonged. A Printing Press and all its appurtenances, next came along.” [10] All the careful preparations made before sailing contributed from that day to the ceaseless flourishing of Yerba Buena. Brooklyn passenger William Glover noted, “There was a continual improvement in the city, almost from the day of our landing.” [11]

Getting the cumbersome five-ton press set up was one of Samuel Brannan’s first challenges. He chose a spot for it on the second floor of an old gristmill. Some wondered about getting it up the rickety outside stairs and onto the second floor. But with many hands helping, it was quickly put in place.

The influx of such a large group taxed the village’s sleeping quarters, so most pitched tents. This made the little town look like an army encampment. The American owner of the Casa Grande, the town’s largest structure, graciously allowed nine families, including Brannan’s, to spread blanket-beds on the floor. Sixteen other families crowded into the customs house, which Montgomery had converted into military barracks, their living spaces being divided by quilts or other flimsy partitions. Cooking was done outdoors. [12]

On Sunday, 16 August, the bedrolls and personal belongings crammed into the Casa Grande were sufficiently cleared to convert it from a dormitory into a chapel for Latter-day Saint services—the first non-Catholic religious meeting in Yerba Buena. The Mexican Roman Catholic priest had fled when Montgomery arrived, so Brannan was the only recognized religious figure in town. Thus, some non-Mormons attended, too, and the crowd spilled out the front door, across the porch, and into the street. John H. Brown, an English sailor who had settled in Yerba Buena the year before, indicated that Brannan’s sermon was the first given at Yerba Buena in the English language and was “as good a sermon as anyone would wish to hear.” [13] Thereafter, Brannan often preached on Sundays. An early historian of San Francisco described Brannan’s preaching style as “fluent, terse, and vigorous.” [14] Later, the people met in various private homes, “being called together by a small hand bell which was rung on Portsmouth Square, usually by Samuel Brannan himself.” [15]

Yerba Buena in the 1840s; shaded area represents

Yerba Buena in the 1840s; shaded area represents

the plaza, now Portsmouth Square

An immediate problem for the new arrivals was food. The Brooklyn had only a one-month supply left. There was little to buy in such a tiny, unsettled place and even less money with which to buy it. However, there were abundant cattle and a little Mexican wheat. The settlers bartered for beef jerky, wheat, and whatever foodstuffs the frequent whaling sliips brought with them.

William Glover cheerlessly recalled that some families had “nothing to eat, but boiled wheat and molasses, until their wives began to take in washing from the sailors and supported themselves and their husbands.” [16] However, Carolyn Joyce gratefully acknowledged, “When I soaked the mouldy shipbread, purchased from the whale-ships lying in the harbor, and fried it in the tallow, taken from the raw hides lying on the beach, God made it sweet to me, and to my child.” [17]

Several other Latter-day Saint women went to work for John H. Brown in his newly opened Portsmouth House hotel: Mrs. Mercy Narrimore as housekeeper, Lucy Nutting as waitress, and Sarah Kittleman as cook.

Not all of the LDS families settled in the village of Yerba Buena. A small group found homes in the old cloistered buildings of the Franciscan Dolores Mission, about four miles to the southwest. Here, nineteen-year-old Angeline Lovett “taught the first school in California where the English language was used.” [18]

The men also sought employment. Though initially hesitating at the suggestion, Captain Richardson, realizing that the Saints were destitute, agreed to accept a shipload of valuable redwood timber to pay off the remaining expense of the voyage. Brannan called for volunteers to go north across the Bay to present-day Marin County where they could obtain the redwood. “Part of the company went to South Seleter [Sausalito],” Glover wrote, “hired a sawmill, hauled the logs, sawed and delivered the lumber and paid the debt.” [19]

Several men got jobs “to make adobies, dig wells, build houses and haul wood to make money to keep up the expenses of the company.” [20] John Horner and James Light went east to Marsh’s Landing (present-day Antioch), where Dr. John Marsh employed them in planting wheat. [21] Some went to work in lumber camps on the Marin Peninsula, in the East Bay hills, and in the Santa Cruz mountains south of the Bay. Others went to work around Sutter’s Fort. Sutter’s Fort had been built only a few years earlier by John A. Sutter, an immigrant from Germany who sought to establish a colony in Central California. The walled compound, located at what is now Sacramento, included storehouses, granaries and other facilities. It was typically the first outpost travelers would reach after crossing the Sierra Nevada. Men from the Brooklyn worked at the Fort and also at the gristmill and the sawmill that Sutter was building in the foothills.

There was also the matter of security. Though the village had been claimed by the United States, it was by no means secure. Mexican soldiers were still around, and they opposed the idea of the Yankees taking over. Skirmishes continued throughout the territory. Montgomery immediately pressed into service the seventy partly prepared soldiers of the Brooklyn to aid him in defending against what he thought could be an imminent Mexican attack. The Saints mostly served as night watchmen, though they drilled daily in the town square in preparation for an attack that never came.

Only an occasional false alarm disturbed the peace. For example, the officer in charge of the marines who guarded the town secretly visited John Brown at the Portsmouth House late each night to have his flask filled with whiskey. He would go to John Brown’s window, rap twice on the shutter, and then say in a barely audible voice, “The Spaniards are in the brush”—a signal that he needed whiskey. One night, Brown was sleeping soundly and did not hear the knocking at his window. In frustration, the officer, who had already been drinking, “fired off one of his pistols, and sang out at the top of his voice, ‘The Spaniards are in the brush.’” Immediately an alarm was sounded in the barracks, and quickly the Saints “were all up and on hand with arms and ammunition, ready to furnish what service they could.” They remained on guard for three hours. “There were several shots fired by those on duty, thinking they were shooting at Californians; but they found the next day, that instead of dead bodies, some scrub oaks had received the shots.” [22]

Capt. John C. Fremont came to Yerba Buena to recruit men foe his “California Volunteers.” At first, many Saints were interested in signing up, but when William Glover pointed out that Fremont’s company included many “Missouri Mobbers,” all but two declined to join. [23] On 15 November, these two participated in the Battle of La Navidad, near Salinas, where the Mexicans defeated Fremont and his soldiers.

New Hope Colony

During the late summer or early autumn of 1846, Samuel Brannan took communal funds to the San Joaquin Valley, about seventy miles east of Yerba Buena, to acquire land and begin a farm. At Marsh’s Landing, Dr. Marsh convinced him to buy a discarded whaleboat, convert it into a sailing launch, and use it to carry supplies up the San Joaquin River. Brannan took farm implements, sawmill irons, seed wheat, and a small flour mill to establish the farm. He also called a crew of twenty men, headed by Thomas Stout, to work the farm. Ezekiel Merritt, an old trapper who knew the area well, drew a map for Brannan of the land he regarded as the “purtiest of all.” [24]

Along the headwaters of the majestic San Joaquin River, at the juncture of the Stanislaus, slept a land of breathtaking natural beauty, boundless level acres, and a climate which rivaled Italy. Its soil, the old trapper assured him, was deep, it had wild game in plenteous abundance, and more important, it possessed a natural waterway to a seaport site on the bay. A more perfect setting could scarcely be imagined. Samuel believed he had marked the site of another Kirtland, Nauvoo, or perhaps even the New Jerusalem of the latter days.

Round about, elk and antelope went in droves by thousands; deer were plentiful; the ground covered with geese; and ricers with ducks, while the willow swamps along the river banks were filled with grizzly bear. The tracks were as well worn in the swamps as cattle paths today. Three hours of good hunting could provide meat enough for a week, for the whole colony. Bear’s oil served as lard, and the only provisions that Samuel Brannan had to send from Yerba Buena were unground wheat, sugar and coffee. [25]

Captain Fremont called the area “scenic as Switzerland, balmy as Italy, and fertile as the Nile Delta.” [26]

Quartus Sparks, one of the twenty called to work at the farm, was dispatched on muleback to Livermore via Santa Clara and San Jose, to buy a yoke of oxen and farming equipment. In the meantime, the others converted the whaler, renamed it the Comet, and made a couple of trips up the river to transport small equipment and seed.

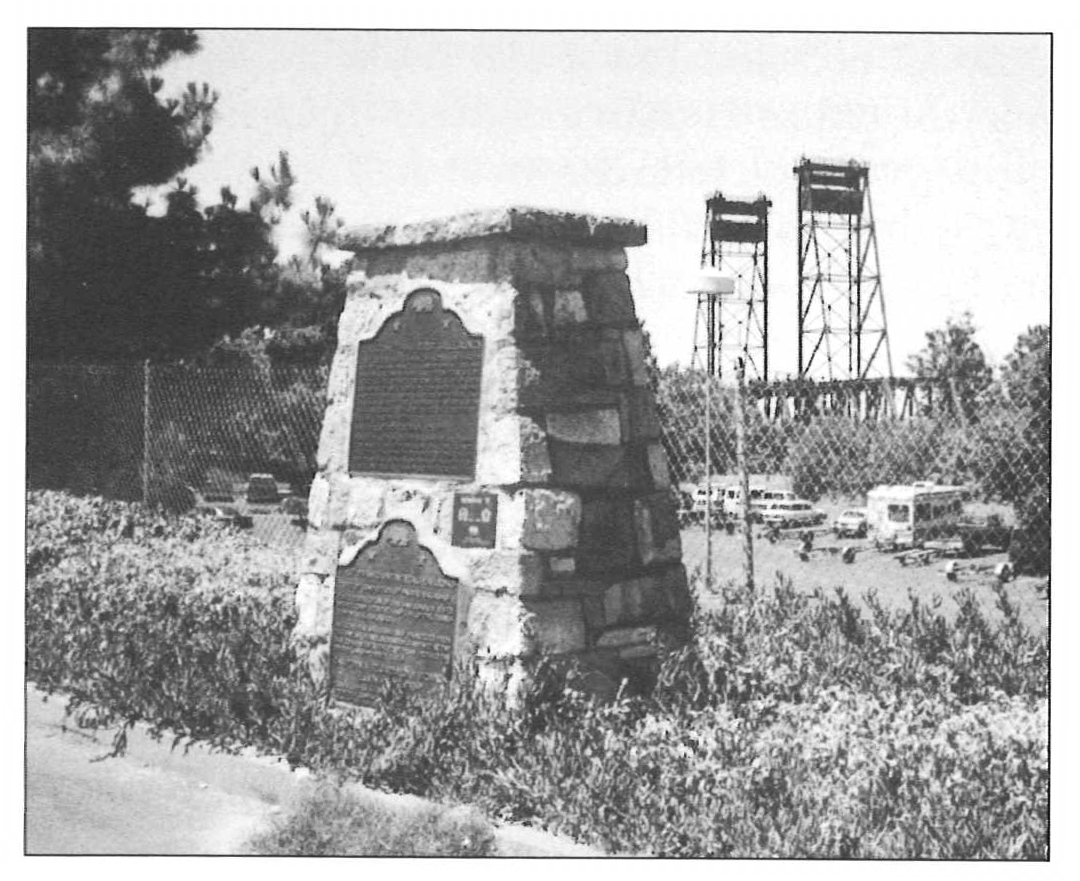

1948 Comet monument with transcontinental railroad bridge in background

1948 Comet monument with transcontinental railroad bridge in background

Sparks, with oxen and mules, met Brannan and the others at Marsh’s Landing. From there they drove over the relatively trailless country into the valley, where they set up camp. A few hours later, the launch arrived carrying heavy equipment. The Comet was the first sailing vessel to ascend the San Joaquin River, and Brannan had the distinction of starting the first farm in the now-famous San Joaquin Valley.

From where the Comet stopped, the men carried the seed wheat, implements, and machinery to the site of “New Hope”—a distance of about twenty miles—on the north bank of the Stanislaus River about a mile and a half from its junction with the San Joaquin. They set to work building three log houses and a gristmill. They fenced and planted eighty acres of wheat, along with vegetables and redtop (a forage crop), hoping to get their seeds into the ground before winter rains set in. However, storms that winter were early and heavy, and most of the crops were lost to flooding.

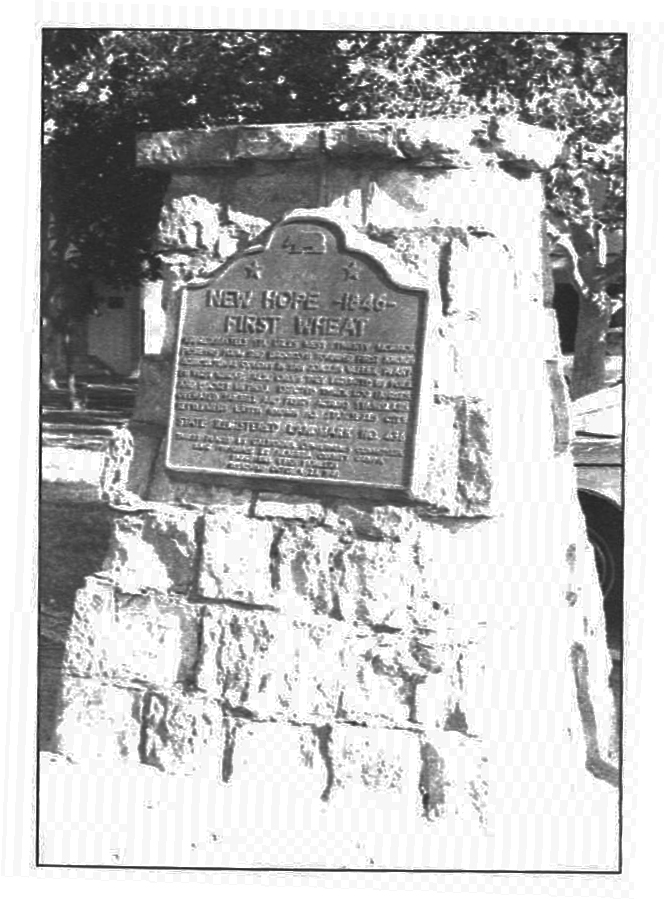

1948 New Hope monument

Growth Continues in Yerba Buena

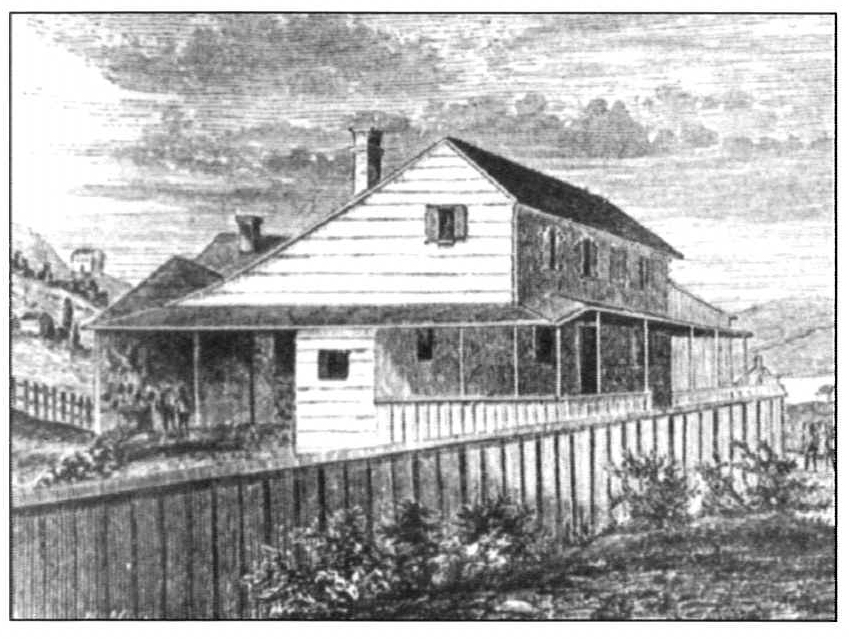

Two of Brannan’s concerns were economics and industry. The communal pact signed aboard the Brooklyn was converted into a firm known as “Samuel Brannan and Company,” which owned all means of production: the printing press, the sawmills, the flour mill, and various other tools and implements. The company also purchased city lots and farms and built homes and other buildings. During the fall of 1846, Brannan moved into a one-and-one-half-story frame home which he had either leased or built (the reports vary). It was located on a prominent corner lot directly behind the old Customs House. [27]

Samuel Brannan's home in San Francisco

Samuel Brannan's home in San Francisco

But the Brooklyn Saints seemed to be no more ready to live under the constraints of a cooperative organization than were those in Kirtland. The grumbling that began on the ship continued and intensified, some feeling that “communal” ownership meant “Brannan” ownership.

Furthermore, Brannan excommunicated three men for drunkenness or other infractions. These, along with the excommunications during the voyage, caused a permanent rift within the Brooklyn colony. Some importuned Captain Montgomery for redress. Brannan complained that “a few of the passengers on our arrival endeavored to make mischief and trouble, by complaints of the bad treatment they had received during the passage, which induced Capt. M. to institute a court of enquiry, before which the larger portion of the company were cited to appear, for private examination. But the truth was mighty and prevailed!” [28]

Another suit was brought against Brannan by William Harris, a non-Mormon who had boarded the Brooklyn in Hawaii. He demanded that he be released from the communal pact and be given his share of the stock. The mayor, Washington A. Bartlett, acted as judge, and a jury of peers was impaneled. Attorneys were found to represent both parties, with Brannan doing most of his own talking. Each of those who had been disfellowshipped testified against him, accusing him of betraying their trust by mismanaging their common funds. Others gave compelling testimony in his behalf. Brannan pointed out that Harris had paid only his fifty-dollar fare but had been supported out of the common stock of provisions; therefore, he “had received more than his services were worth.” Furthermore, if the association were to pay its debts, there would be nothing left to divide. The court decided in Brannan’s favor, “that the contract, which had been signed for three years, could not be broken.” Thus ended California’s first jury trial. [29]

Despite the clamor, by the fall Brannan was earning a steady income publishing documents and bulletins for government officials and the general public. On 24 October, he published an “extra” in advance of his newspaper, which began regular publication two and one-half months later. He had planned this paper while still in the East and had prepared a masthead bearing the title the California Star.

Overland Arrivals

On 29 October 1846, a Latter-day Saint pioneer family arrived with the Lilburn W. Boggs wagon train from Missouri. Thomas Rhoads, a Kentuckian, joined the Church in Illinois in 1835 and was ordained an elder in Missouri in 1837. Though he was apparently a faithful Church member, he remained in Missouri, owning land and slaves after the general exodus of the Saints in 1839.

Upon learning of the expulsion of the Saints from Nauvoo, and possibly with direction from Brigham Young, Rhoads gathered most of his family and some friends together and headed west for California, planning to join the Saints there. Why Rhoads was travelling with the notorious Latter-day Saint enemy, Boggs, or how many others in the party were Church members, is not known.

After passing through Emigrant Gap, or Donner Pass (just a few weeks before the ill-fated Donner Party became stranded there), the Rhoads family settled East of Sutter’s Fort in the vicinity of Dry Creek and the Consumnes River. The older daughters soon married prominent non-LDS pioneers in the area. The Rhoads family participated in two of California’s most famous pioneer experiences. Sons John and Dan figured prominently in the rescue of the Donner Party that winter, and Thomas may have been the true discoverer of California gold, mining it successfully for some time before Marshall’s more famous discovery in 1848.

Another group coming overland in 1846 included a Latter-day Saint widow, Lavina Murphy, and her family. She had been hired by the Donner Party as a cook and a laundress, to pay her family’s way. Although she and two sons died, four other children survived. One of these was Mary, for whom the city of Marysville wad named. [30] There is no record that the Murphy children had any subsequent affiliation with the Church.

Besides the Rhoadses and the Murphys, other individuals and small, independent parties of Saints came to California in 1846. Among them was the Wimmer family, some of whom were present at the discovery of gold. This family is sometimes confused with the Winner family of the Brooklyn.

Thus Latter-day Saints were in California while it was still a Mexican province. They came as pilgrims and as farmers. Though they hailed from both the North and the South, they were primarily from New England and played a vital role in setting the American tone of what would later become the most populous state in the United States.

Some of the authenticated “firsts” attributed to these pioneers in California are as follows: the first Anglo birth (a baby born to the William Glovers); the first marriage (Lizzie Wimmer and a serviceman, Basil Hall, performed by Brannan); the first divorce (hotel owner J. H. Brown and Hettie Pell); the first court case (several Brooklyn passengers v. Brannan); the first English language school (Angelina Lovett’s); and the first wheat grown in the San Joaquin Valley.

As the Brooklyn and other Latter-day Saint immigrants helped set the early tone in Northern California, another larger group was coming to the South—the “Mormon Battalion,” which was undertaking an epic march. This battalion would soon play its own role in planting Latter-day Saint and American ideals in early California soil.

Notes

[1] A. E. Beach to Thomas O. Larkin, 24 December 1845 in The Larkin Papers, ed. George P. Hammond (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1953), 4:129.

[2] John H. Everett to Thomas O. Larkin, 12 December 1845, in Larkin Papers, 4:119,121.

[3] A. P. Nasatir, “The French Consulate in California, 1843–56,” California Historical Society Quarterly 11 (December 1932): 355.

[4] Hubert 11. Bancroft, Archives of California; Department of State Papers, IX–XVI; Misc., 9:16–17, as quoted in Lorin Hansen, “Voyage of the Brooklyn,” Dialogue (fall 1988): 65 n. 13.

[5] Larkin to the Secretary of State, 6 March 1846 in Larkin Papers, 4:232.

[6] Bancroft, 5:551.

[7] The Californian: Facsimile Reproductions (San Francisco: John Howell, 1971), 3.

[8] Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (New York: Tullidge and Crandall, 1877), 447.

[9] Joseph T. Downey, Filings From an Old Saw, ed. Fred Blackburn Rogers (San Francisco: John Howell, 1956), 45–6.

[10] Ibid., 47.

[11] William Glover, The Mormons in California (Los Angeles: Glen Dawson, 1954), 19.

[12] Augusta Joyce Crocheron, “The Ship Brooklyn,” Western Galaxy 1 (1888): 83.

[13] John H. Brown, Early Days of San Francisco (San Francisco: Presses Grabhorn #13, 1933), 34.

[14] Zoeth Skinner Eldredge, The Beginnings of San Francisco from the Expedition of Anza, 1774 to the City Charter of April 15, 1850 (New York: John C. Rankin, 1912), 2:710.

[15] Florence M. Dunlap, “Samuel Brannan” (master’s thesis, University of California at Berkeley, 1928), 45.

[16] Glover, 21–22.

[17] Tullidge, 446.

[18] Annaleone D. Patton, California Mormons by Sail and Trail (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1961), 16.

[19] Glover, 18.

[20] Ibid.

[21] John M. Horner, “Adventures of a Pioneer,” Improvement Era 7, no. 8 (June 1904): 571.

[22] Brown, 39–40.

[23] Glover, 19.

[24] San Jose Pioneer, 23 June 1877.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Patton, 21.

[27] Frank Soulé, John H. Gihon, and James Nisbet,The Annals of San Francisco(New York: D. Appleton, 1855), 347.

[28] California Star Extra, 1 January 1847, quoted inMillennial Star9 (15 October 1847): 307.

[29] Soulé, Gihon, and Nisbet, 750–51; see also Dunlap, 46–48.

[30] Erwin Gudde,California Place Names(Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974), 194.