Buildings and Blessings: 1950–1964

Richard O. Cowan and William E. Homer, California Saints: A 150-Year Legacy in the Golden State (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1996), 337–64.

Even before the excitement of postwar celebrations had faded, a spirit of sacrifice and hard work was beginning to take hold among California Latter-day Saints. As the Saints turned their energies to building the kingdom of God in California, their efforts were met with success. As they worked and sacrificed, they were being blessed. California prospered, giving them the necessary means to build the kingdom. These were years of serious, purposeful work and the rewards that came with it.

Not only was the state graced with beautiful temples and permanent meetinghouses in the 1950s and 1960s, but these years were also productive in other ways. This was yet another period of remarkable growth. California missions, after decades of few convert baptisms, were now numbered among the most successful in the Church. At the same time, thousands of Latter-day Saints from other areas continued to move into the Golden State. Church membership nearly tripled, from just over one hundred thousand in 1950 to almost three hundred thousand in 1965. The number of stakes more than tripled, from eighteen to fifty-nine. Attendance of men at priesthood meetings in the Los Angeles Stake was ninth best in the Church in 1952, and other statistics showed similar patterns. [1] Significantly, a California stake president, Howard W. Hunter, was called to Churchwide service as a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.

Presiding over this dynamic period of growth was David O. McKay, who was seventy-seven years of age when he succeeded George Albert Smith as President of the Church in 1951. With his noble bearing, flowing white hair, and quiet sense of humor, journalists remarked that he looked and acted like a prophet.

The Building Program Accelerates

Construction of many of the buildings needed for the growing Church had been postponed during the Depression and subsequent war. There now was a need to make up for lost time, and construction on local meetinghouses and other Church buildings was begun at more than a hundred locations in the Golden State. And plans for the two California temples were reactivated.

Over the years, the California Saints contributed nearly half of the money needed for buildings, although the ratio of local to general Church funds for a given project depended on the size, activity, and economic strength of individual congregations. Carrying on such an extensive building program required sacrifice, and the Saints responded.

The Beverly Hills Ward tried for many years to collect enough money for a ward chapel. After many dinners, carnivals, etc., they had little to show for all their efforts. At length they decided to host an evening of entertainment to raise funds. The husband of a member donated a night at his theater. The ward, however, could not find a headliner.

The ward bishop, C. Dean Olson, a successful businessman, used his position as mayor of Beverly Hills to contact the world-famous entertainer Danny Thomas—not a Latter-day Saint but a resident of the community. In the gracious and generous spirit for which he was known, Thomas agreed to help, and over twenty thousand dollars was raised for the ward building fund. [2]

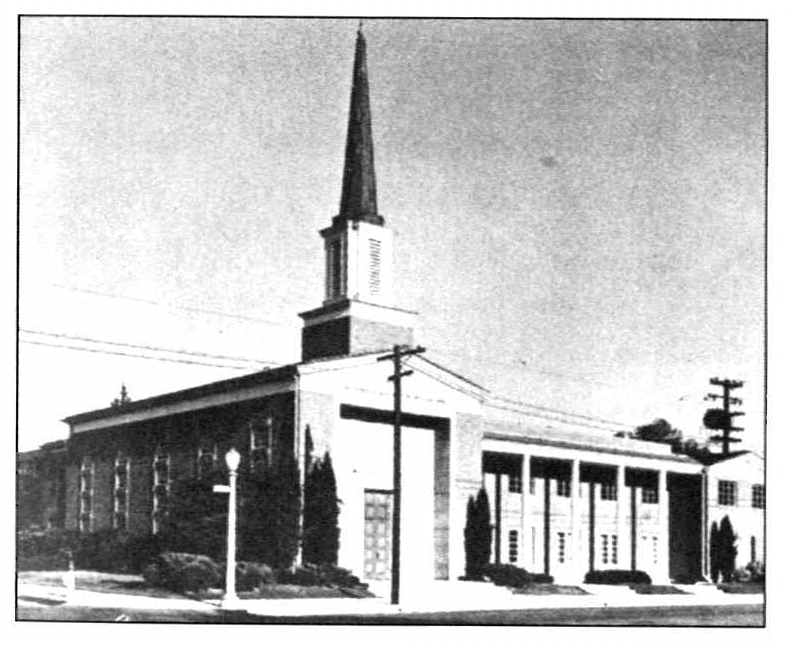

Experience in designing and erecting hundreds of chapels throughout the Church enabled the General Building Committee to develop a series of standardized plans incorporating the most desirable features and minimizing costs. Generally a simple, pleasant, and functional design was used. Costs were further reduced by designing most meetinghouses to serve two or more congregations. Small buildings that could be expanded easily one phase at a time were built in places where congregations were not large. An LDS meetinghouse took on a distinctive, easily recognized look.

Typical post-war meetinghouse, at Fresno

Typical post-war meetinghouse, at Fresno

Another significant thrust of the Church’s building program was to provide facilities for education. Because David O. McKay was the first Church President to hold a college degree and had been an educator prior to his call as an apostle, he became a powerful advocate for the Church Educational System. Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, which had been a small college since 1875, was expanded into a major university. California LDS college students in large numbers began going to BYU to receive a good education within a Church environment. As they returned, BYU alumni in California swelled to over thirty thousand.

In the 1950s the Church also considered developing a system of junior colleges to provide greater numbers of Latter-day Saint students the opportunity to attend a Church school. Land was acquired for construction of junior colleges in San Fernando Valley, Anaheim, La Verne, and Fremont City. [3] Ultimately the Church abandoned the junior college idea, opting instead to establish or strengthen institutes of religion adjacent to existing universities and colleges.

President Hunter’s Challenge

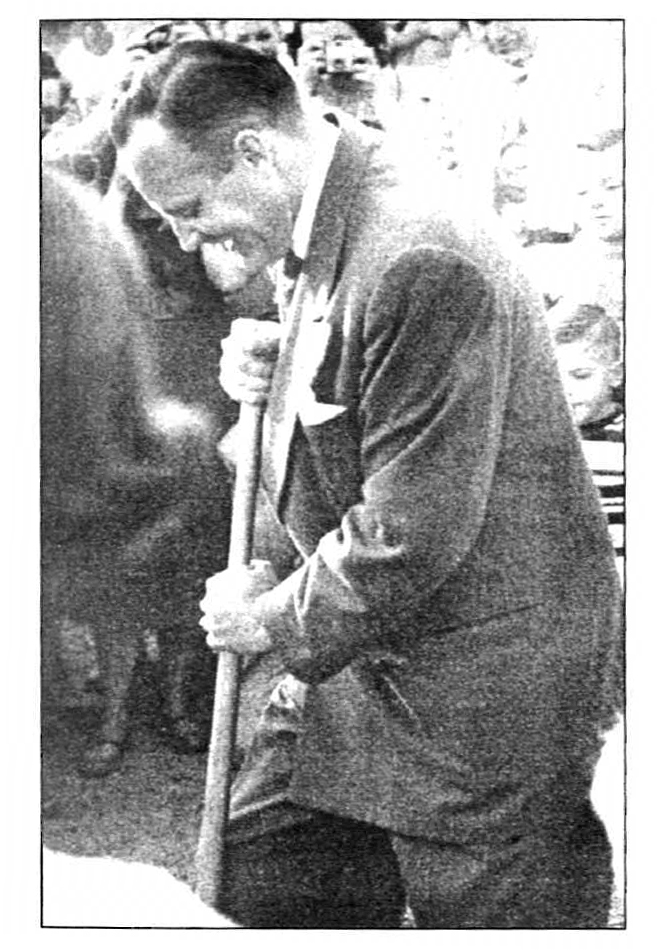

Like other California stake presidents, Howard W. Hunter faced the difficult task of acquiring funds and property for a stake center. A two-and-one-half-acre site, to be shared between the Pasadena Stake and the East Pasadena Ward, was found in a good Sierra Madre neighborhood. After the site was purchased, the stake members needed to raise $400,000 as their contribution toward the construction of the building.

Under President Hunter’s leadership, the stake planned an impressive stake center. The twenty-five-thousand-squarefoot building included a 375-seat chapel for worship, and a cultural hall larger than a basketball court for socials, dances, dramatics, sports, and other activities. Like other LDS chapels, this building included numerous classrooms for the Sunday School and other organizations, as well as specialized rooms for Primary, seminary, Boy Scouts, and Relief Society. The building committee realized that it needed to seize this opportunity to accommodate the large and growing stake and at the same time create an architectural statement reflecting their sense of the stake’s excellence.

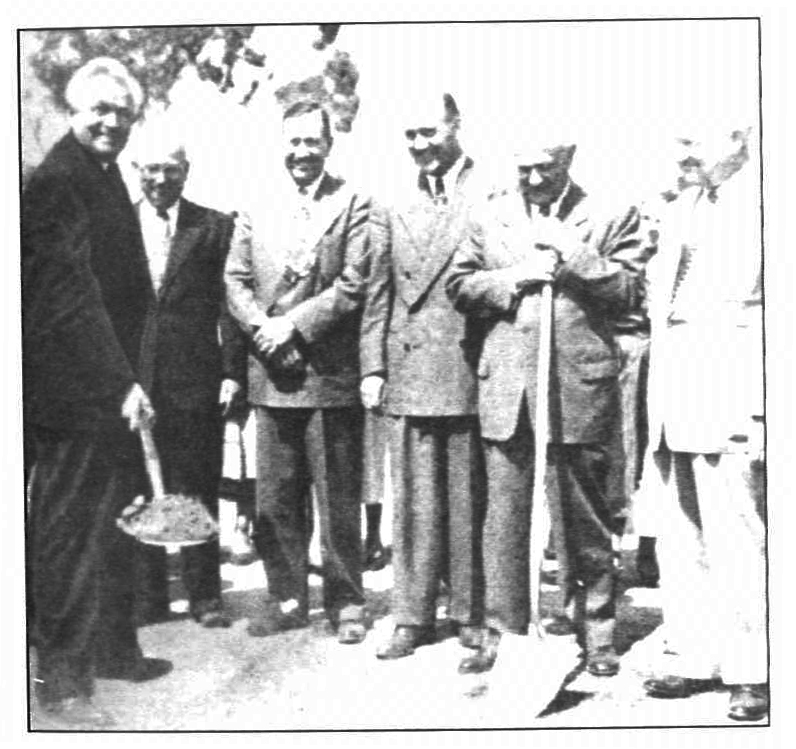

Stake president Howard W. Hunter at Pasadena groundbreaking

Stake president Howard W. Hunter at Pasadena groundbreaking

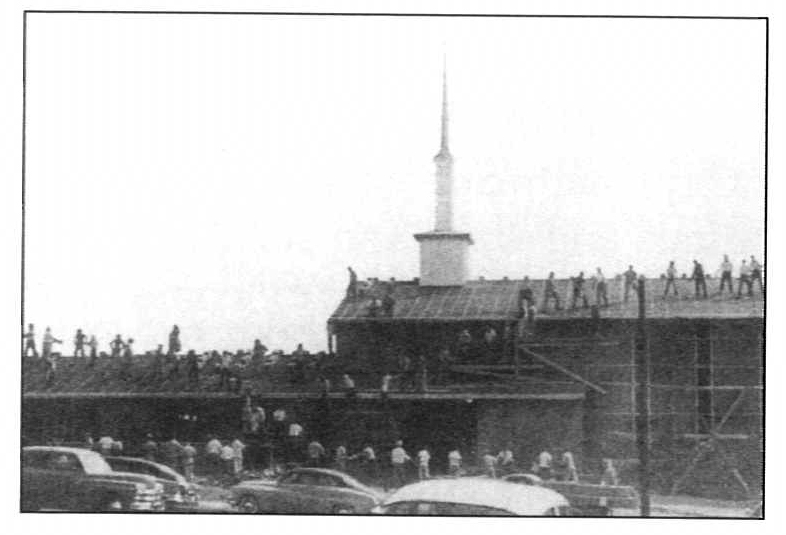

Although numerous fundraising events followed, the project ran out of funds in the summer of 1953. Stake members were carrying a heavy burden: they had three other chapels and a camp facility under construction. They were also operating multiple welfare projects and were actively raising funds for the Los Angeles Temple. In addition to these contributions they paid tithing (which went to Salt Lake City) and made generous contributions to local missionary funds and ward and stake budgets. They often donated 15 percent or more of their incomes and most of their spare time working on buildings and welfare projects.

One evening at 11:30 P.M. in the summer of 1953, President Hunter announced to the stake’s bishops that “they were closing down the project for lack of funds.” One of the bishops responded that he thought this would be a mistake: “Why not invite the priesthood of the stake to come and see what they are investing in?” [4]

The idea caught fire, and a special priesthood conference was set for Sunday, 16 August 1953—the first meeting of any kind in the partially complete stake center. President Hunter and other stake leaders told the group of the predicament and outlined what was needed to finish the building. Then “we sat down and waited for their response,” President Hunter recalled. “A long period of silence ensued before, one by one, individuals stood up and pledged their support.” The building committee was prepared with blank souvenir checks printed with a picture of the building, pledge forms, and receipts. More than twenty-three thousand dollars was raised on this occasion. [5]

An example of the sacrifices made during the period was related by a bishop: “Among my souvenirs is a small glass piggy bank which recalls happy memories of a successful fund-raising drive. . . . The bank belonged to a young man, Steven Terry, who had been working and saving for a trip to Europe with the All-American Boys’ Band. Steven gave up his dream trip to Europe, and brought his piggy bank and entire savings and donated it.” [6]

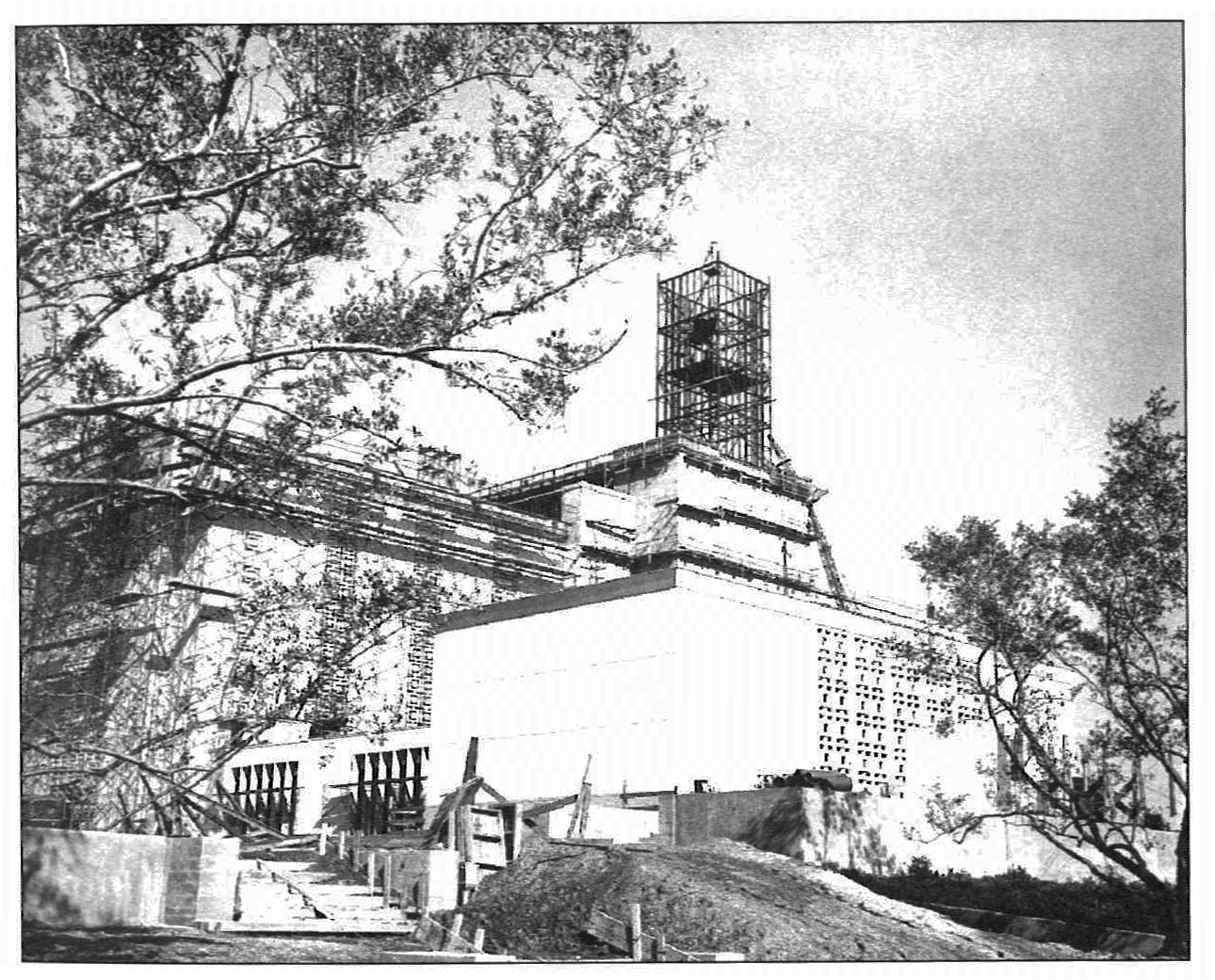

Pasadena stake center under construction

Pasadena stake center under construction

Such sacrifices brought stake members closer together and developed a powerful feeling of unity among them. President Hunter’s dream was realized when the stake center was dedicated on 6 June 1954. Not quite two years later, the stake was divided again, and many who contributed became members of the new Covina Stake and started over.

The Los Angeles Temple

During the late 1930s, plans had been prepared for a temple in Los Angeles which would accommodate two hundred persons per session, but further preparations were suspended because of World War II. On 17 January 1949 President George Albert Smith announced at a meeting of Southern California Church leaders that the time had arrived to build the temple. Conferring with city officials, he expressed his desire that the temple be a “contribution to the architecture and culture of the community.” [7]

California Saints believed that President Heber J. Grant had been blessed with inspiration a decade earlier when he chose the Santa Monica Boulevard site, as it was “the highest point in elevation between Los Angeles and the ocean.” Furthermore, the freeway network, planned years after the site was purchased, would provide excellent access. [8]

President Smith appointed Edward O. Anderson, a member of the prewar board of temple architects, to design the temple. Rapid growth in California prompted President Smith to enlarge the design to accommodate three hundred persons per session, the same as in the Salt Lake City Temple, and to add a large assembly room on the upper floor—the first of only two such facilities to be built in the twentieth century. [9]

Anderson prayed for the same inspiration that had guided earlier temple architects, so that his design “might express in appearance” and facilitate “the spiritual work to be carried on” in the temple. A staff of twenty-eight specialists assisted in preparing the sixty-three large sheets of plans. Anderson and his associates worked closely with the First Presidency, from whom they received inspiration and direction. He later gratefully acknowledged that whenever a problem arose “the answers or individuals we needed were forthcoming.” [10]

Plans called for a six-story building, 364 feet long and 241 feet wide, containing about four and one-half acres of floor space, surmounted by a tower more than 257 feet high. [11] Only one other building in Los Angeles was taller: the Los Angeles City Hall. When completed, the temple was visible to ships twenty-five miles out to sea.

President McKay, succeeding President Smith, recognized the influence Church buildings, particularly temples, had in areas such as California where there was often turmoil, and where the Latter-day Saints were a small, sometimes unknown, minority.

Los Angeles attorney and Church member Preston D. Richards donated his services by contacting various government bureaus and explaining the purposes of the temple to them. “When these men realized the importance of the temple and reviewed the record of Latter-day Saints living in California,” they were pleased to help “in every way to obtain the necessary permits.” [12] Final approval was received from the Los Angeles City Council early in 1951. Ground was broken on 22 September of that same year. LeGrand Richards, Presiding Bishop of the Church and former president of the Hollywood Stake, remarked that the groundbreaking would be “one of the most important events in the history of the world.” [13]

Presidents David O. McKay (left) and Stephen L. Richards (second from right)

Presidents David O. McKay (left) and Stephen L. Richards (second from right)

at Los Angeles Temple groundbreaking

Two weeks later, during the October general conference, stake presidents in the temple district met with President Stephen L Richards, first counselor to President McKay, to receive their assignments for fund-raising. They were told that of the building’s estimated four-million-dollar cost, one million would be their “fair share.” President Noble Waite of the South Los Angeles Stake and chairman of the fund-raising committee later commented that President Richards did not know how he nearly “knocked out fourteen stake presidents with that statement,” as this would average more than seventy thousand dollars per stake. “We kept our chins up,” President Waite continued, “and it was only afterwards when we got out, and we confided in each other that really we were staggered. But we had received the commission, and so our instructions before we left were to make a plan, organize, and submit the plan, and get the approval of the First Presidency and then we would be given the green light to go forward.” [14]

A pledge card was created, and each individual was invited to “determine for himself and according to his own circumstances the size of his Temple contribution.” [15] President McKay came to Los Angeles on 3 February 1952 and officially launched the fund-raising campaign. He told twelve hundred leaders of stakes and wards that the Church was about to begin construction on the “largest temple ever built in this dispensation.” He also counseled them to let the “young people, even the children in the ‘cradle roll’ [nursery], contribute to the temple fund, for this is their temple, where they will be led by pure love to take their marriage vows.” [16]

When one twelve-year-old deacon pledged $150, his bishop thought the boy had inadvertently put the decimal in the wrong place. However, the youth assured him it was no mistake. It took two years, but the young man paid the full amount from his paper-route and lawn-cutting earnings. [17] Throughout Southern California the Saints responded generously, raising over $1,648,000—well over the amount originally requested. During this same period other Church donations did not suffer but actually increased. Tithe paying, for example, rose 45–50 percent. [18]

In August 1952 construction on the temple began. Many workers found it a spiritual experience. Workdays uniformly began with prayer, and construction was completed without serious accident. Though 80 percent of the construction workers were Church members, at least four others asked for baptism for themselves and their families.

The temple was constructed of reinforced concrete, specifically engineered to withstand California earthquakes. It was faced with perfectly matched crushed-stone panels, which were etched with acid in such a way that the stone crystals sparkled in the light. The Buehner brothers of Salt Lake City received the contract to provide the stone, which they regarded as a fulfillment of their father’s prophetic patriarchal blessing decades before, which stated that his family would “help erect temples of this Church.” [19] One of the brothers reported that when the unique material was chosen for the temple’s exterior, “there was just enough to make the stone for this building and the Bureau of Information [visitors center]—no more, no less.” [20]

Los Angeles Temple under construction

Los Angeles Temple under construction

The Los Angeles Temple’s cornerstone was laid on 11 December 1953. A party of sixty-seven, including more than twenty General Authorities, arrived from Salt Lake City by train. They were met at the downtown depot by local Saints in sixteen cars and were taken directly to the temple site about twelve miles away, escorted by two motorcycle policemen, one of them Albert J. Aardema, bishop of the nearby Elysian Park Ward. [21]

Some ten thousand members—the largest gathering of Latter-day Saints in California to that date—witnessed the placing of the commemorative copper box, containing historical memorabilia, into the cornerstone. Countless others listened by radio as the ceremony was broadcast in Los Angeles and Salt Lake City. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors honored the Saints by presenting a formal resolution congratulating the Church. [22]

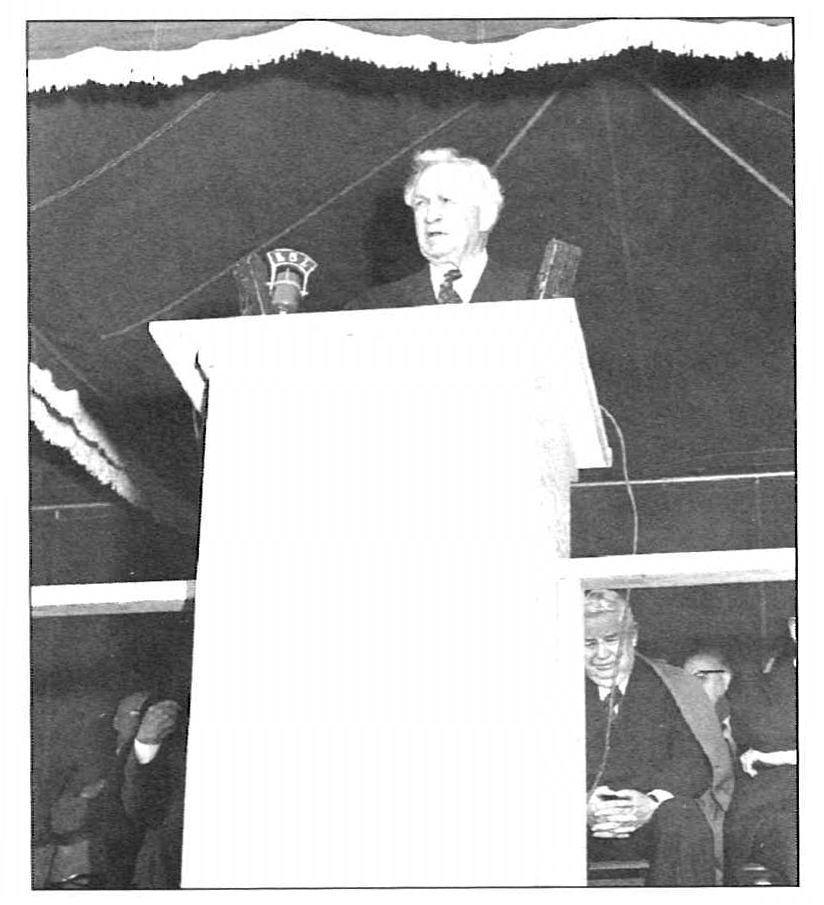

David O. McKay speaking at Los Angeles Temple cornerstone laying;

David O. McKay speaking at Los Angeles Temple cornerstone laying;

to his left are his second counselor, J. Reuben Clark Jr., and

Joseph Fielding Smith, president of the Twelve

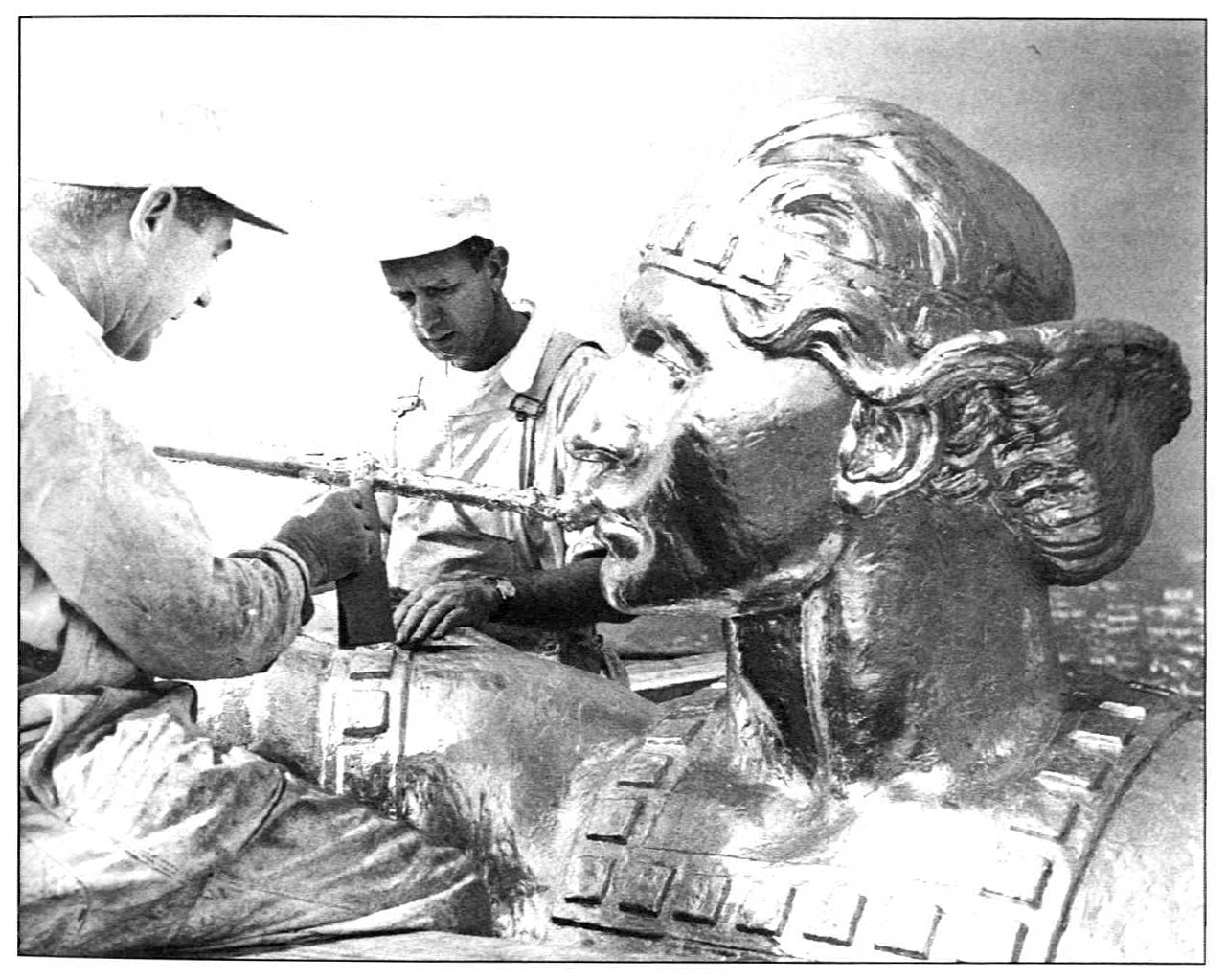

A fifteen-and-one-half-foot statue of Moroni was sculpted by Millard F. Malin and cast in aluminum in New York. In October 1954, the one-ton figure, coated with twenty-threecarat gold, was hoisted to the roof and placed on the tower. At first the angel faced southeast toward the front of the temple. But soon afterwards, at the request of President McKay, it was turned to face east as a symbol of watching for Christ’s Second Coming.

The story was told of a neighbor who lived east of the temple and who was asked if she had visited the temple grounds. She replied, “No, I’m waiting until the angel turns around and faces me.” She later said, “Imagine my surprise when I woke up one morning and discovered that the angel was looking right down my street.” [23]

Workmen put finishing touches on Los Angeles Temple statue of angel Moroni

Workmen put finishing touches on Los Angeles Temple statue of angel Moroni

During construction, so many visitors stopped at the site that a temple mission was created with LDS volunteers to answer questions and conduct guided tours of the grounds so that the work could progress uninterrupted. While full-time laborers did the actual building, Church members—some highly paid professionals—performed clean-up work around the site. They also prepared the thirteen-acre grounds for landscaping.

Olive, palm, pine, and Chinese ginkgo trees, as well as other trees and plants, came from all over the world. Teenage Latter-day Saint girls from the area contributed roses for a beautiful garden. [24]

During a fifty-one-day open house, nearly seven hundred thousand persons—an average of twelve thousand per day—visited the temple, often waiting in line for many hours. A local television station carried an hour-long program featuring the new landmark.

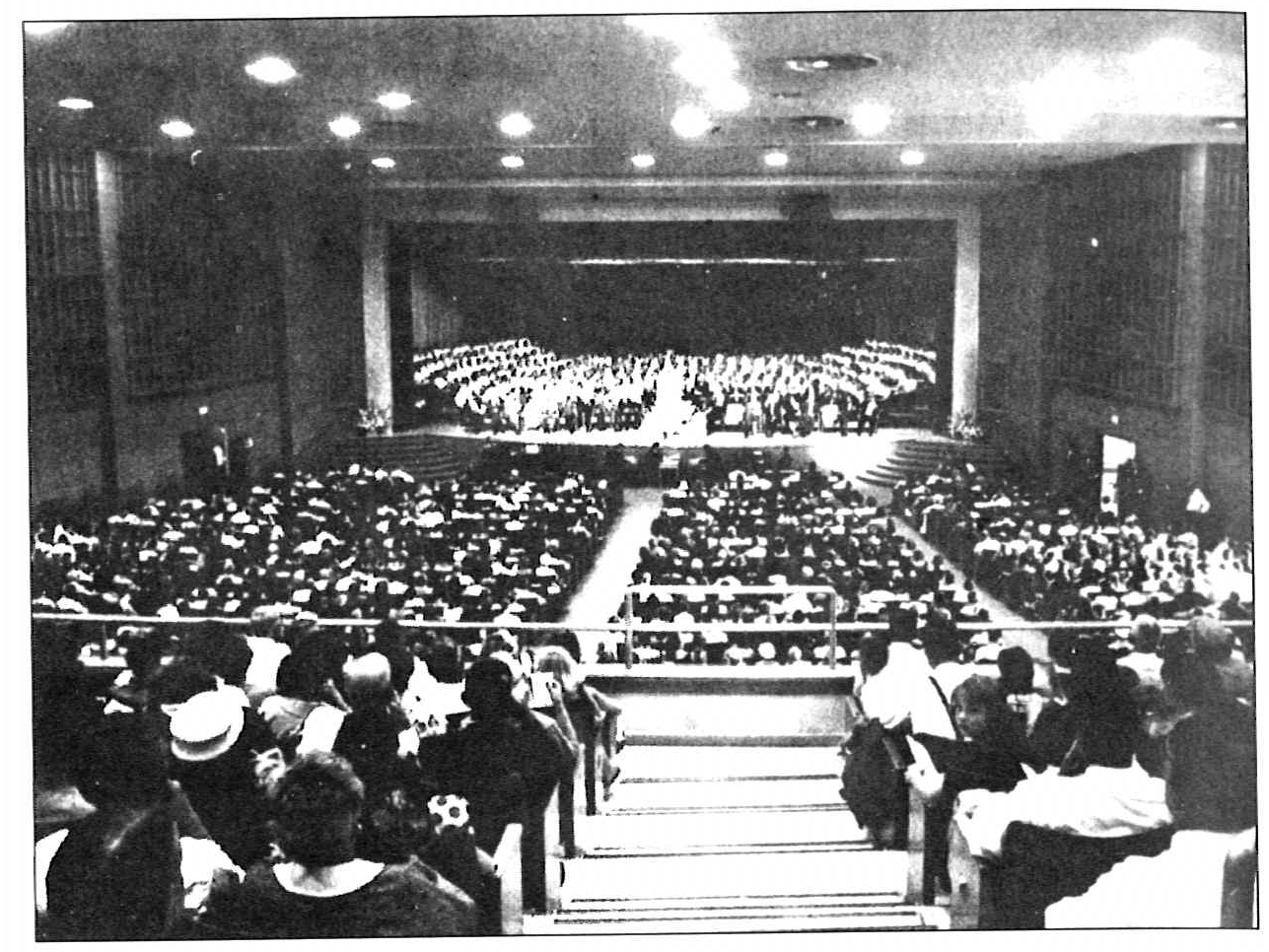

The temple was dedicated in eight sessions, from 11 to 14 March 1956, by President David O. McKay. The services were open to all qualified Church members, and over fifty thousand—nearly sixty-seven hundred per session—attended, seated not only in the assembly hall, but also in many other places inside, where they viewed proceedings over closed-circuit television.

With their new temple, the Southern California Saints no longer felt that they lived in “some sort of ‘outpost’ either spiritual or temporal.” [25] Yet even with the opening of the Los Angeles Temple, some California Saints still had to travel long distances. Two years after the temple’s dedication, “the temple advisory committee recommended that the Church construct housing specifically for temple workers on Church-owned property near the temple.” These “Temple Patrons’ Apartments” were opened in 1966. [26]

The Oakland Interstate Center and Temple

Over the years, Oakland’s Temple Hill changed considerably. New freeways were announced, and a neighborhood was developed nearby. The Oakland Stake concluded that Temple Hill would be ideal for its stake center, and the First Presidency approved. In Berkeley, meanwhile, a site had also been acquired and was being developed for another stake center.

It was at this time that Stephen L Richards of the First Presidency called a joint meeting of the two stake presidencies. He spoke of the rapid growth of the Church, its demanding building program, and the wisdom of avoiding duplication. He suggested a joint building for the two stakes which eventually could be used by many stakes, an attractive place where members could gather close to a temple.

Berkeley Stake leaders recognized that the two stakes working together could afford a more adequate facility than either one alone. The decision to work together was fortuitous because before construction even began, the Oakland and Berkeley Stakes were realigned to form three stakes: Walnut Creek, Oakland-Berkeley, and Hayward.

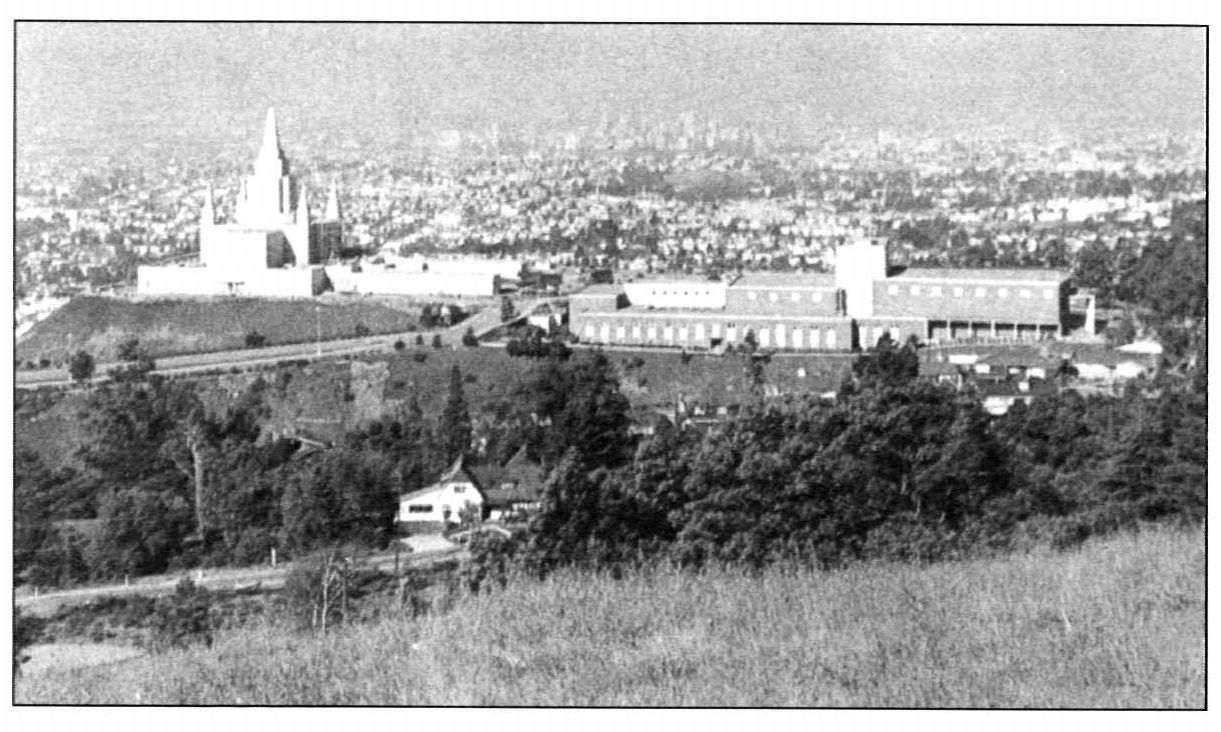

On 20 July 1957 ground was broken for “the East Bay Interstake Center.” It was dedicated by President McKay and opened on 16 October 1959. The center was originally a large red-brick structure on the northeast corner of the hill. Later, when the white temple was completed, the Interstake Center was painted white to match. It occupies more than seventyseven thousand square feet—approximately an acre and a half—just five thousand feet less than the adjacent temple. It contains an auditorium seating 2,180 persons, and a recreation hall large enough for two simultaneous basketball games. The recreation hall can seat one thousand persons for banquets and twice that number for meetings. Between the auditorium and the recreation hall is a large stage with curtains front and rear, permitting its use with either room.

President David O. McKay at dedication of Oakland Interstake Center

President David O. McKay at dedication of Oakland Interstake Center

Among other things, the facility has been used as a home for Oakland civic light opera, a training center for the city’s disaster preparedness team, a practice gym for the Golden State Warriors professional basketball team, a site for Martin Luther King Day commemorations, a hall seating over four thousand to hear football star Steve Young speak, and a theater for a temple pageant.

On the way to the airport following the dedication, Oakland-Berkeley Stake president O. Leslie Stone reminded President McKay that there were 120,000 Church members still anxiously awaiting a temple in Northern California. Just over a year later, on 23 January 1961, President McKay summoned the stake presidents in the area to a special meeting and showed them sketches of a proposed temple. He appointed two stake presidents, O. Leslie Stone and David B. Haight (of the Palo Alto Stake), to head the temple committee.

The design President McKay presented features a modern oriental motif, reflecting the San Francisco Bay Area’s unique heritage. A rooftop garden graces the top of the first level, and a fountain and artificial brook cascade down through the center of the temple’s north gardens. The central tower rises 170 feet, and four tapering pinnacles, one on each corner, rise ninety-six feet. A sculptured panel facing the temple’s north court portrays the Savior commissioning his apostles in the Old World, and a similar panel facing south features Christ’s appearance in ancient America as described in the Book of Mormon. [27]

As in Los Angeles, the Saints in the north were given a target amount of money, four hundred thousand dollars, to raise. However, the temple committee felt that the people would contribute more and therefore raised the goal to five hundred thousand dollars. As in Los Angeles, one and one-half times the targeted amount was raised.

The San Jose Stake raised their allotment in a single day. As was done in Los Angeles, a day was set aside to visit every household. However, rather than pledge-cards, checks were received. At the end of the day, the stake’s entire allotment was deposited. Stake president Horace Ritchie remarked that “it was the finest single achievement accomplished since the organization of the Stake.” [28] As had been the case in Southern California, the general level of Church activity accelerated as the temple was built.

On Saturday, 26 May 1962, ground was broken. Work on the temple then continued uninterrupted, and the cornerstone was laid on 25 May 1963 with President McKay officiating.

Prior to its dedication, this temple was also opened to the public, and some 350,000 people toured the $2.5-million building. The temple has 265 rooms and a total floor area of 82,417 square feet—less than half the size of the Los Angeles Temple but still among the largest in the Church. The reinforced concrete structure is faced with Sierra white granite from Raymond, California, which gives it a gleaming exterior. The 18.3-acre site sits on a hill with spectacular views of Oakland, Berkeley, San Francisco, and the Bay’s five bridges.

Elder George Albert Smith’s 1924 vision of a gleaming white temple on the Oakland hills that could be seen by ships entering San Francisco Bay was literally fulfilled. One Friday afternoon during the public viewing, a chauffeured government car parked at the entrance, and a navy officer stepped out and introduced himself as the commander of a ship which had sailed in through the Golden Gate early that morning. He had observed on the foothills of east Oakland a new landmark. He docked his ship and arranged to come and see for himself what it was. [29] California Latter-day Saints knew that the construction of the Los Angeles and Oakland temples was the fulfillment of Brigham Young’s 1847 declaration that “in process of time the shores of the Pacific may be overlooked from the temple of the Lord.” [30] It took just over one hundred years, but instead of one, there were now two temples prominently overlooking the Pacific. A third would follow before the end of the twentieth century.

Oakland Temple and Interstake Center

Oakland Temple and Interstake Center

On 17 November 1964 the Oakland Temple was dedicated by President McKay. Now ninety-one years of age, he had recently suffered a stroke that left him virtually speechless and unable to walk or stand. When he came to the dedication, General Authorities and his own family despaired that he would not be able to take any meaningful part and were certain that he would not rise or speak. However, President McKay was brought to the speaker’s podium in a wheelchair and assisted as he stood and grasped the pulpit. He began to speak as clearly as he had before his stroke. His son recorded: “[My wife], with tears running down her cheeks,. . . whispered, ‘Lawrence, we’re witnessing a miracle.’ I nodded in agreement. Members of the Council of the Twelve were crying. Father finished his talk and, still standing, dedicated the building.” [31]

After the services, Lawrence McKay sought out Dr. J. Louis Schricker, President McKay’s physician, and asked if the prophet would be able to deliver the dedicatory prayer again in the afternoon session. Dr. Schricker answered, “Lawrence, this is out of our hands. If I hadn’t been here to see it, I wouldn’t have believed it.” President McKay not only delivered the prayer that afternoon but also in the morning and afternoon sessions of the following day. [32]

The Oakland Temple employed a new method of presenting instructions associated with the endowment. Rather than making the presentation in a series of four rooms with muraled walls, modern audio-visual equipment was used to make the entire presentation in a single lecture room. Two such rooms, each seating two hundred persons, were provided, making it possible for two groups to receive the endowment simultaneously. The temple was also one of the first to take advantage of the Church’s new computer system. Traditionally, temples had performed vicarious baptisms, endowments, and other ordinances for individuals whose names had been submitted to them by individual researchers. When the Los Angeles Temple opened, however, the number of ordinances performed in the Church’s temples began to exceed the number of names being submitted. Employees at Church headquarters were therefore authorized to identify names from vital records which had been microfilmed by the genealogical department and submit them to the temples.

Having these genealogical records on microfilm meant that copies could be reproduced inexpensively. This enabled the Church to develop a vast system of branch genealogical libraries. One of the first, located in the basement of the Los Angeles Temple visitors center, was dedicated on 20 June 1963. It soon became one of the largest in the Church. [33]

A Musical Classic Is Born

While the Church was building beautiful chapels and temples in California, the Golden State made a significant contribution to Latter-day Saints worldwide in a rather different way. Out of this period of struggle and sacrifice emerged a Latter-day Saint musical classic. Mildred Tanner Pettit, of the Pasadena Stake, composed the music for “I Am a Child of God” for a Primary meeting at the April 1957 general conference in Salt Lake City.

After receiving the assignment, she “woke up one night with the music running through her mind and immediately wrote it down.” The song’s coauthor, Naomi Randall, said the words had come to her “in a similar way.” [34] Since then, the song has been a favorite throughout the world. Although a simple children’s song, it is powerful enough to move adults. It is now included in the Church’s hymnbook.

An Apostle from California

Some of the California leaders who played key roles in planning and constructing the two temples would go on to provide significant Churchwide service. In October 1959 the Pasadena Stake president, Howard W. Hunter, became an apostle. He later described how he received his call. Following the opening session of general conference he received word to go to President David O. McKay’s office as soon as possible.

President McKay greeted me with a pleasant smile and a warm handshake and then said to me, “Sit down, President Hunter, I want to talk with you. The Lord has spoken. You are called to be one of his special witnesses, and tomorrow you will be sustained as a member of the Council of the Twelve.”

I cannot attempt to explain the feeling that came over me. Tears came to my eyes and I could not speak. I have never felt so completely humbled as when I sat in the presence of this great, sweet, kindly man—the prophet of the Lord. He told me what a great joy this would bring into my life, the wonderful association with the brethren, and that hereafter my life and time would be devoted as a servant of the Lord and that I would hereafter belong to the Church and the whole world. He said other things to me but I was so overcome I can’t remember the details, but I do remember he put his arms around me and assured me that the Lord would love me and I would have the sustaining confidence of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve.

The interview lasted only a few minutes, and as I left I told him I loved the Church, that I sustained him and the other members of the First Presidency and the Council of the Twelve, and I would gladly give my time, my life, and all that I possessed to this service. He told me I could call Sister Hunter and tell her. . . . I went back to the Hotel Utah and called Claire in Provo, but when she answered the phone I could hardly talk. [35]

The following morning, Church leaders were presented for a sustaining vote to the eight-thousand-member congregation seated in the Salt Lake Tabernacle. “My heart commenced to pound as I wondered what the reaction would be when my name was read,” Elder Hunter remembered. “I have never had such a feeling of panic. One by one the names of the Council of the Twelve were read and my name was the twelfth.” After the vote he was invited to take his place among the apostles on the stand. “I felt the eyes of everyone fastened upon me as well as the weight of the world on my shoulders. As the conference proceeded I was most uncomfortable and wondered if I could ever feel that this was my proper place.” [36] Howard W. Hunter would himself become the prophet and president of the Church in 1994.

Upon his return home he “found a large stack of mail, phone messages, and telegrams from well-wishers. His call to the Twelve had been reported in the major Los Angeles newspapers, some with front-page stories. One longtime client who called to congratulate him commented that ‘the Church must have made a very attractive offer’ to entice him to leave his successful law practice.” [37]

Elder Hunter wrote in his journal: “Most people do not understand why persons of our religious faith respond to calls made to serve or the commitment we make to give our all. I have thoroughly enjoyed the practice of law, but this call that has come to me will far overshadow the pursuit of the profession or monetary gain.” [38]

Howard W. Hunter plays piano at farewell gathering

Howard W. Hunter plays piano at farewell gathering

The two stake presidents who served as cochairmen of the Oakland Temple Committee also became General Authorities. David B. Haight, mayor of Palo Alto and governor of the San Francisco Bay Area Council of Mayors, gave up these positions to serve as president of the Scotland Mission. He was then called as an Assistant to the Twelve in April 1970 and became a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles six years later. O. Leslie Stone, former vice-president of the Safeway grocery chain, became an Assistant to the Twelve in October 1972.

Thus ended a decade and a half which was a high-water mark for the Latter-day Saints in California, climaxing in President McKay’s miraculous dedication of the Oakland Temple and the call of a California Saint to be a member of the Quorum of the Twelve. Sacrifice and hard work had brought substantial progress and a feeling of peace and permanence only dreamed of by previous generations. The dedication and spirit of Church members in California were never stronger. But this peace would not last, and strength would be needed to meet the tumultuous challenges ahead.

Notes

[1] Chad M. Orton, More Faith Than Fear: The Los Angeles Stake Story (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft), 198–99.

[2] Ibid., 202.

[3] Ernest L. Wilkinson and Leonard J. Arlington, ed., Brigham Young University: The First One Hundred Years (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), 3:148–56.

[4] Susan Kamei Leung, Hozv Firm a Foundation: The Story of the Pasadena Stake (Pasadena, Calif.: Pasadena California Stake, 1994), 37.

[5] Eleanor Knowles, Howard W. Hunter (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994), 129; Leung, 37–38.

[6] As quoted in Leung, 42.

[7] Journal History, 17 January 1949; LDS Church Archives.

[8] Orton, 180.

[9] George Albert Smith Diary, 8 November 1949; Western Americana Collection, University of Utah; Edward O. Anderson, “The Los Angeles Temple,” Improvement Era 56 (April 1953): 225–26; 58 (November 1955): 804.

[10] Anderson, Improvement Era 58 (November 1955): 803; Church News, 5 December 1953, 9.

[11] Church News, 13 December 1950, 2.

[12] Anderson, Improvement Era 56 (April 1953): 226.

[13] Orton, 181.

[14] In Conference Report, October 1952, 75.

[15] Orton, 182–83.

[16] Quoted in Richard O. Cowan, Temples to Dot the Earth (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1989), 153.

[17] California Intermountain News, 27 September 1955, 46.

[18] Church News, 28 March 1981, 3.

[19] Quoted in Cowan, 143.

[20] Carl W. Buehner, Do Unto Others (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1957), 153; see also Church News, 8 May 1954, 1, 8.

[21] California Intermountain News, 27 September 1955, 3, 45.

[22] Church News, 19 December 1953, 6–12.

[23] Orton, 187; Cowan, 155–56.

[24] Albert L. Zobell Jr., “Los Angeles,” Improvement Era 66, no. 11 (November 1963): 953.

[25] Leung, 44.

[26] Orton, 244.

[27] Harold W. Burton and W. Aird Macdonald, “The Oakland Temple,” Improvement Era 67, no. 5 (May 1964): 383, 386.

[28] Delbert F. Wright, “Building the Oakland Temple,” 15; Oakland Stake Collection.

[29] Ibid., 70.

[30] Journal History, 7 August 1847; see chapter 6.

[31] David Lawrence McKay, “Remembering Father and Mother,” Ensign, August 1984, 40.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Orton, 238.

[34] William W. Tanner oral history, quoted in Orton, 311; Leung, 42.

[35] Knowles, 144–45.

[36] Ibid., 145–46.

[37] Ibid., 151; Leung, 44.

[38] Knowles, 151.