Zion's Co-operative Mercantile Institution

The Rise and Demise of the Great Retail Experiment

Jeffrey Paul Thompson

Jeffrey Paul Thompson, "Zion's Co-operative Mercantile Institution: The Rise and Demise of the Great Retail Experiment," in Business and Religion: The Intersection of Faith and Finance, ed. Matthew G. Godfrey and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 65–92.

One of the most surprising developments of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the nineteenth century was the emergence of the ZCMI department store. It is unique in the annals of retail history for a religious organization to create and sustain such a vast merchandising enterprise. Even more surprising is that its original purpose was not a capitalistic venture aimed at promoting consumerism but, rather, an effort to prepare the Saints to live communitarian principles in order to establish the city of God on earth. Its full moniker was Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution, a delightfully antiquated name to twenty-first century ears, but it was best known for most of its life by its acronym. Initially, ZCMI was successful in promoting an independent economy and in laying the groundwork for living the United Order in the Utah Territory. However, almost as quickly as the cooperative system had been espoused by the Church, ZCMI would be forced to abandon many of its founding principles because of internal and external pressures. ZCMI would continue for another century as more of a private concern than a cooperative one in the form of a popular local department store. The ultimate demise of ZCMI in the late twentieth century provides an interesting example of the changing focus and values of the Church in regard to its business concerns.

The Rise

The formation of ZCMI can be traced back to theological underpinnings from the formative years of the restored gospel. From its beginnings in the early 1830s, the Church had attempted to promote and live economically egalitarian principles in an effort to establish a Zion community. Converts were familiar with the description in the Bible of early Christian congregations where “all that believed were together, and had all things common; and sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need” (Acts 2:44–45). The Book of Mormon validated such economic equality among the righteous: the society that formed following Jesus’s visit to the Nephites was described as a community where “they had all things common among them; therefore there were not rich and poor” (4 Nephi 1:3). Additional revelations emerged through Joseph Smith that further confirmed such living conditions among the righteous. His new translation of Genesis, which came forth in December 1830, described the city of Enoch taken to heaven because of its virtuous inhabitants: “And the Lord called his people Zion, because they were of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them” (Moses 7:18). In revelations received in 1831 and 1832 for then-current members of the Church, they were reminded that “it is not given that one man should possess that which is above another, wherefore the world lieth in sin” (Doctrine and Covenants 49:20), and “if ye are not equal in earthly things ye cannot be equal in obtaining heavenly things” (Doctrine and Covenants 78:6).

With such a doctrinal basis, it was not startling when Smith received a revelation in February 1831 that would establish the “law of consecration and stewardship.” The Law mandated that all real and personal property be turned over to the Church with each member being allocated enough provisions “as is sufficient for himself and family,” with the surplus kept by the Church to provide for the indigent and for the “building up of the New Jerusalem” and the temple (see Doctrine and Covenants 42:30–36).[1] The revelation also made this interesting statement about clothing: “And again, thou shalt not be proud in thy heart; let all thy garments be plain, and their beauty the beauty of the work of thine own hands” (Doctrine and Covenants 42:40). Leonard Arrington has pointed out that implementing the Law achieved a threefold purpose: first, it provided an alternative to the experimental social orders with which many early converts had been involved (such as the Disciples of Christ to which Sidney Rigdon belonged); second, it served as a religious incentive to share the surplus property for the operational expenses of the Church and provide charitable contributions to the indigent; and third, it was intended to realize the economic parity described in scripture.[2]

There were attempts to live the Law in Kirtland, Ohio, and in Jackson County, Missouri, in the early 1830s, as well as later on, in a slightly modified form, in Far West, Missouri, in the late 1830s. However, several problems plagued its successful implementation, including members’ unwillingness to relinquish title to property, idleness among participants, defectors suing for the return of donated property, as well as the ongoing persecutions experienced by the Church during that period.

The Law, curiously, was not practiced during the Nauvoo period. However, it was during this time that we find early evidence of the idea of cooperative merchandising circulating among the Saints. In an interesting little article in the Nauvoo Neighbor newspaper, it was reported that on the evening of 12 March 1844 members of the Tenth Ward met

at the school house on the hill, in Parley Street, to take into consideration the propriety of establishing a store on the principle of co-operation or reciprocity. The subject was fully investigated, and the benefits of such an institution clearly pointed out. The plan proposed for carrying out the object of the meeting was by shares of five Dollars each. The leading features of the institution was to give employment to our mechanics, by supplying the raw material, and manufacturing all sorts of domestics, and furnishing the necessaries and comforts of life on the lowest possible terms. A Committee was appointed to draft a plan for the government of said institute, to be submitted for adoption or amendment at their next meeting, after which an adjournment took place till next Tuesday evening, at half past six o’Clock, at the same place.[3]

The residents of Nauvoo had, undoubtedly, become aware of the cooperative merchandising experiment going on in Rochdale (near Manchester), England, through British converts and recently returned missionaries, Brigham Young among them.[4] Nothing more is known about these efforts reported in the newspaper: they presumably dwindled in the chaos of the ensuing months. In retrospect, it is interesting to note that several elements discussed at this meeting—that it would be called an “institution,” that it would involve manufacturing and retailing, and that the value of the stock was set at five dollars—would be characteristics of ZCMI when it was established in Utah twenty-five years later.

Though the Saints would organize and work together during their mass migration across America and in establishing settlements throughout the Intermountain West, it would be another decade before a formal communitarian Church program would emerge under Brigham Young. Preached from the pulpit at the general conference of April 1854 and reiterated in a subsequent official epistle, members of the Church were reminded that “now there were no obstacles from a full and frank compliance with the law of consecration, as first given by Br. Joseph.”[5] The result was the execution of “consecration deeds” by thousands of members throughout the Utah Territory, from the mid-1850s to the early 1860s, donating all property to the Trustee-in-Trust of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although these deeds were legal conveyances recorded at the county seats, the properties never escheated to the Church, and stewardships were never assigned. It is not exactly clear why this program was never fully effectuated. In the end, as Leonard Arrington has observed, the signing of these consecration deeds “proved to be a symbolic gesture—faith and the willingness of the Saints literally to lay all they possessed upon the altar.”[6]

In conjunction with promoting the consecration deeds, Young also promoted local and home manufacturing, which he saw as a crucial element in creating an isolated and self-sufficient economic system. He challenged the Saints to “raise your own wool and flax; make your own leather; and manufacture your own clothing, soap, candles, oil, sugar, molasses, glue, combs, brushes, glass, iron, and every other article within your reach” in order to save their money to fund missionary work, to help immigrants, and to build temples.[7] This admonition, unfortunately, went largely unheeded as Church members predictably favored factory-made merchandise.

A few years later, in 1864, under the direction of Apostle Lorenzo Snow, the Brigham City Mercantile and Manufacturing Association was established in northern Utah. The Brigham City experiment began as a cooperative store, followed by the establishment of a tannery and then flourished into an extensive local network with, among other things, a shoe factory, a woolen mill, a cattle ranch, and a dairy, and it was all supported by local farming and home manufacturing. It would become a tremendously successful realization of Young’s vision. Other settlements followed the trend, on a smaller scale, such as the Spanish Fork Co-operative Institution organized in 1867.[8]

The mid-1860s seemed to be the moment when Young realized he had one last chance of creating an economy that would be independent of the vagaries of the greater American economy and would help the Saints “to be better able to build up the Kingdom of Zion.”[9] There were several factors that spurred his decision to move forward. First, he was undoubtedly encouraged by the success of the Brigham City experiment: in the thirty-plus years of failed attempts to implement a communitarian economic system, the experiment in Brigham City was the only one that actually succeeded. Second, Young knew that the coming of the transcontinental railroad would result in exploitation of the newly opened Utah market by Eastern merchants who would seek to usurp the local market. Third, Young saw it as a perfect opportunity to remove antagonistic “gentile” (as he called them) merchants, many of whom were simply out to take advantage of the Saints by charging exorbitant prices for scarce goods: for example, in the summer of 1866 sugar was selling for $1 per pound (about $15.60 in 2016 dollars).[10] In addition to price gouging, many of these merchants were vituperative and caustic in their criticisms of the Church and of Young in particular, and their presence had had a negative effect on Salt Lake City; East Temple Street (now Main Street) was colloquially known as “Whiskey Street” because of the abundant availability of that beverage.

Young’s first offensive measure was to institute a boycott of hostile merchants. In the October 1865 general conference, Young urged the members of the Church, in an unequivocal message,

to do their own merchandising and cease to give the wealth which the Lord has given us to those who would destroy the kingdom of God. . . . Cease to buy from them the gewgaws and frivolous things they bring here to sell to us for our money and means . . . and let every one of the Latter-day Saints, male and female, decree in their hearts that they will buy of nobody else but their own faithful brethren.[11]

This boycott, though targeted only at those merchants who were antagonistic toward the Church, escalated the tension. During the following twelve months, relations worsened in large part because of the unsolved murder of Dr. J. King Robinson, with Young’s opponents attempting to implicate Church leadership.[12] The acrimony and friction reached new heights and culminated right before Christmas in 1866 when twenty-three retailers sent a letter with an ultimatum addressed to Young agreeing to leave Utah if the Church would buy them out.[13] It must have been a moment relished by Young as he knew he had won the war and politely declined the offer: “Your withdrawal from the Territory is not a matter about which we feel any anxiety, so far as we are concerned, you are at liberty to stay or go, as you please,” but he refused to buy them out.[14] The boycott spread quickly throughout the territory, and the effect was immediate in some instances: stores operated by people who were not members of the Church like Firman & Munson in Nephi and J. H. McGrath’s in American Fork quickly closed in late December 1866 because of the loss of Latter-day Saint patronage.[15]

By 1868, with the boycott a solid success, it was clear what direction Young wanted to go. Young had reinstituted the School of the Prophets, with local chapters set up in the various communities throughout the territory. Among other things, one of the main purposes was to discuss local economics. It was here in the School of the Prophets that the idea of a cooperative wholesale and retail merchandising organization was discussed, promoted, and adopted as a way of achieving Young’s goals.[16] The general conference of the Church in October 1868 was devoted entirely to moving forward with such efforts.

Following the conference, Brigham Young wasted no time in galvanizing the Church to move forward. Meetings were held throughout the Territory to gain support, and ZCMI was formally organized on 15 and 16 October with subscriptions for the initial $50,000 worth of stock, with Brigham Young purchasing $25,000 and William Hooper and William Jennings each purchasing $5,000, thus becoming the three principal stockholders. Other initial shareholders included John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow. Brigham Young was elected president and William Hooper as vice president. The other executive positions were filled by early Church luminaries such as William Clayton as secretary, and George A. Smith, Franklin D. Richards, and George Q. Cannon on the board of directors.[17]

During the first few months after the organization of ZCMI, it acted more as a mercantile association than a cooperative. The Eldredge & Clawson store became the first establishment to display the ZCMI sign in November 1868.[18] A few months later, in February 1869, it was announced that William Jennings was donating his store and $75,000 in return for stock in ZCMI, and the owners of the Saddler & Teasdale store also joined.[19] But, in general, the Salt Lake City retailers were not enthusiastic about this new proposition and were dragging their feet about the whole venture. This greatly upset Brigham Young, especially since the outlying communities were very supportive—case in point was the Provo Co-operative Institution that was organized on 4 December 1868. Initially, it was intended that the Provo Cooperative would be independent from ZCMI, but when Church leadership intimated that Provo would become the center of the Utah cooperative movement unless the Salt Lake merchants got on board, they conceded and joined ZCMI.[20]

ZCMI officially opened for business on 1 March 1869 in the Eagle Emporium building on the southwest corner of Main Street and 100 South.[21] Ten days later the former Eldredge & Clawson store in the Old Constitution Building (on the west side of Main Street between South Temple and 100 South) opened as part of ZCMI with such goods as grocery, stove, queensware, hardware, and farming tools.[22] These two outlets were exclusively for the wholesale of goods. Seven weeks later, ZCMI opened its first retail outlet in the Main Street store of S. Ransohoff & Company, which had been run out of business.[23]

The ZCMI business model consisted of a parent wholesale operation based in Salt Lake City with local independent retail stores created by wards and communities throughout the territory. Each retail store had its own constitution and bylaws and would purchase its goods exclusively from the parent institution, similar to modern franchise operations. Each local store also issued its own stock, and since Young wanted as many people to share in the wealth as possible, stocks were often offered at $5–10 per share.[24] Brigham Young sent the call out for the establishment of such stores at the general conference in April 1869, and the response was immediate: within days there were eighty-one co-op stores established throughout the Intermountain West settlements,[25] with sixteen separate stores established by the wards in Salt Lake City alone.[26]

The new ZCMI monopoly, as anticipated, quickly reduced the business of non-ZCMI merchants and garnered impressive revenues. Within a couple of years, in addition to the central operation in Salt Lake City, wholesale branches were opened in Ogden and Logan, Utah, and Soda Springs, Idaho. Over 150 independent retail co-op stores opened up in Utah, Idaho, Arizona,[27] and there is evidence that there was one as far away as Deadwood, South Dakota[28]—an impressive feat by any standard but particularly so since this was decades before the concept of the chain store was exploited by Frank W. Woolworth and James C. Penney. In addition to setting up a co-op store, most wards also set up local manufacturing concerns, including dairies, tanneries, woolen mills, lumber mills, and ironworks. The ZCMI network provided an outlet for these manufactured goods with sales totaling $965, 350 in just the first seven months.[29] By 1873 gross receipts had reached over $5 million per annum.[30]

The innovation and financial success of the ZCMI system has, at times, overshadowed its true purpose of preparing the Saints to live a higher law. Brigham Young, however, was very explicit in describing his motives for its establishment: “this co-operative movement is only a stepping stone to what is called the Order of Enoch, but which is in reality the order of Heaven.”[31] He further promised the Saints that “if we succeed in doing this we shall be prepared to inherit life everlasting in the presence of the Father.”[32] These spiritual aspects are clearly evident in the founding documents and original organization.

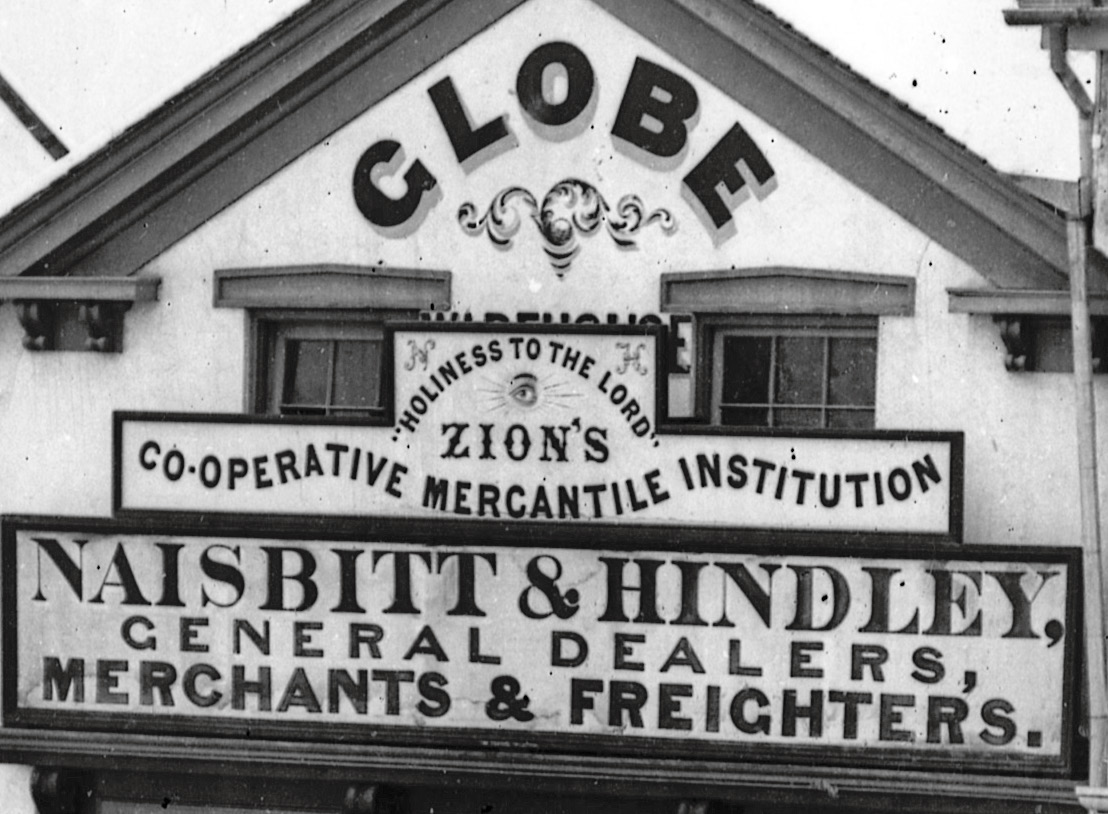

The ZCMI constitution and bylaws, adopted on 24 October 1868, demonstrate the focus on these celestial goals. First, of course, there was the moniker with “Zion” (the city of God) as the defining word. Second, only members of the Church who were in good standing and full tithe payers were allowed to own stock. Third, the logo containing the words “Holiness to the Lord” and an all-seeing eye was required to be displayed at all branches. And fourth, the most unique aspect in terms of business organization for a nineteenth-century business was that it was organized to have “perpetual succession”—organized to last for eternity—instead of the usual fixed-term limit.[33]

A guiding principle of the organization of ZCMI was that establishing the local co-op stores would eradicate poverty and be for the benefit of the community at large. This message was a main thrust of the April 1869 general conference where Young exhorted the members:

When you start your Co-operative Store in a ward you will find the men of capital stepping forward, and one says, “I will put in ten thousand dollars,” another says, “I will put in five thousand dollars.” But I say to you, bishops, do not let these men take five thousand dollars or one thousand, but call on the brethren and sisters who are poor and tell them to put in their five dollars or their twenty-five. . . . do not let these men with capital take all the shares, but let the poor have them. . . . we want the poor brethren and sisters to have the advantage of it.[34]

Storefronts along Main Street in Salt Lake City display signs showing their affiliation with ZCMI

Storefronts along Main Street in Salt Lake City display signs showing their affiliation with ZCMI

circa 1869. Much more than just a marketing ploy, “Holiness to the Lord” indicated that participation was preparation for living a celestial law. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

Even the building was viewed as a sacred edifice. When ZCMI officially opened for business, the Eagle Emporium was treated like a church or temple with an official dedication service. Young and several other leaders gathered together and dedicated “every particle of the building from the foundation to the roof with all its contents” and then opened the doors and declared ZCMI open for business. Young then made the first purchase.[35]

Detail from above showing “Holiness to the Lord” on the store sign.

Detail from above showing “Holiness to the Lord” on the store sign.

Just as the law of consecration and stewardship practiced in the 1830s and the consecration deeds executed in the 1850s were seen as outward expressions of inner faith, so was shopping exclusively at ZCMI in the 1860s and 1870s. Amusing at it sounds today, failure to shop at ZCMI was considered a serious offense and would warrant Church discipline. Brigham Young conceded that people would say, “‘O it is hard that we cannot go and spend our money where we please.’ You may go and trade where you please, I tell you, with the promise that, by and by, you will go out of the Church, and you will go to destruction.”[36] If a member of the Church was found to have patronized a non-ZCMI establishment, he would be brought before the School of the Prophets for an official censure as demonstrated in this example from the School’s minutes: “Bro. Wilkinson was charged with having bought goods from a Jew. He confessed, asked forgiveness and promised not to do so anymore.”[37] Another example became part of the folklore of Weston, Idaho. In 1871, some farmers took their crops to Corinne to sell and, with the proceeds, went shopping and found a bargain on stoves ($37.50 instead of the going price of $50 at the ZCMI store) and brought them home to surprise their wives, many of whom were cooking on their knees over an open flame. Word soon got out that they had not purchased them through ZCMI, and Bishop Maughan threatened excommunication. The following Sunday was a lively event as these farmers were publicly excoriated. Some confessed and one brother even offered to discard his stove in order to be forgiven, which they all were. But apparently the temptation to get good deals was even had among Church leaders: the same Bishop Maughan was later caught shopping in Corinne himself. [38] Another particularly embarrassing episode occurred when Bishop Phineas Young (brother to Brigham) confessed to buying a sack of sugar at the Elephant Store in Salt Lake and was reprimanded and then expelled from the School of the Prophets.[39]

But the ultimate proof of ZCMI’s spiritual purpose was evidenced when it became the springboard for the establishment of the United Order of Enoch throughout the Intermountain West. Many of the cooperative enterprises were fully incorporated into the United Order as part of that ideal socioeconomic construct. In 1875 Brigham Young openly declared that “in the absence of the necessary faith to enter upon a more perfect order revealed by the Lord unto the Church, this [Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution] was felt to be the best means of drawing us together and making us one.”[40]

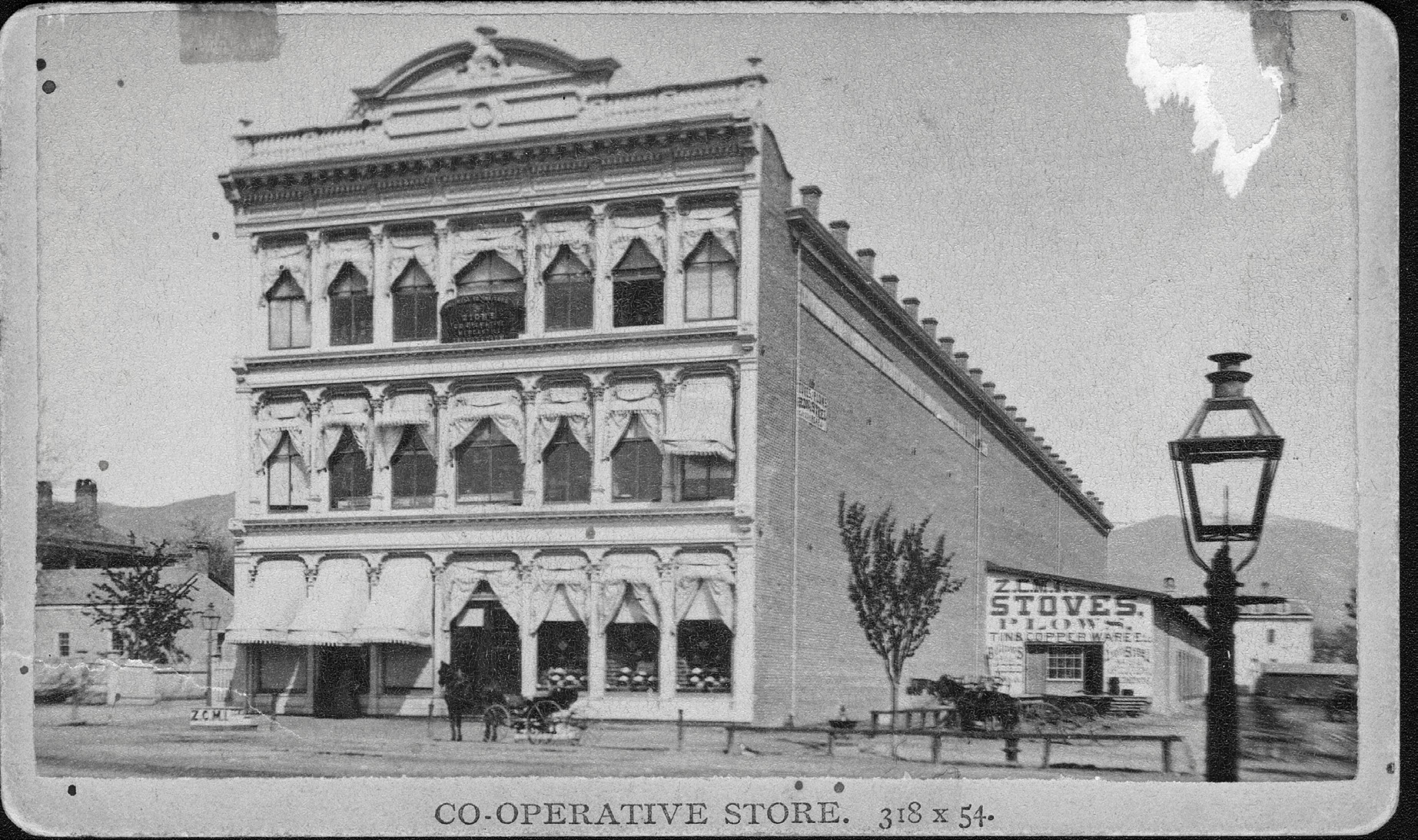

ZCMI flagship store in Salt Lake City circa 1878 before two additions tripled its frontage

ZCMI flagship store in Salt Lake City circa 1878 before two additions tripled its frontage

on Main Street. The original façade was successfully integrated into the new City Creek

Center development in 2012. Courtesy of the Church History Library.

The Transition

The relationship between ZCMI and the Church would be dramatically redefined over the next decade. As strident as Brigham Young was for all things cooperative and communitarian, his successor John Taylor was, ultimately, less committed. By the early 1880s, there had been substantial change in the local economy and in ZCMI and its local co-op stores. The “parent” ZCMI was doing reasonably well running its wholesale operations and the large retail store in Salt Lake City, but the local “child” co-ops were not doing as well. Plagued with problems like poor management, irresponsibly extending credit, and accepting payment in kind rather than cash, many were in mediocre financial standing. Furthermore, the stock of the local co-ops was no longer owned by large numbers of the local populace but was, in most cases, concentrated in the hands of a few. This brought criticism to the whole cooperative mercantile system because it was not achieving any of its original goals. Taylor (who would later serve as president of ZCMI from 1883 to 1887) found himself defending the validity of ZCMI at the Church’s general conference in 1880.[41] Within two years, because of these ongoing pressures, on 1 May 1882, by means of an official epistle, Taylor announced that the ZCMI monopoly was over and that Latter-day Saints could now establish their own mercantile enterprises without any censure from the Church.[42]

This move was significant for two reasons. First, it brought back free-market capitalism into Utah and could have potentially reintroduced all the prior problems with antagonistic merchants that the creation of ZCMI had abolished. Second, and more importantly, it also signaled the end of Church leadership’s belief and commitment to ZCMI as a method of preparing the Saints to live celestial laws and to build Zion.

The dissociation of the Church and ZCMI continued through the tumultuous years of “The Raid.” In 1886, to keep Church assets from being seized by the US government because of the imminent passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act, all ZCMI stock held by the Church (amounting to 36 percent of the shares) was transferred to a holding company headed by Heber J. Grant or sold off.[43] Less than two decades after its founding, the institution that had once been so all-encompassing in the life of the territory was no longer partially owned by the Church. Although the Church president would continue to serve as president of ZCMI and most of the board members were Latter-day Saints, its transition into a secular business seemed complete when ZCMI ceased paying tithing on cash dividends to the Church in 1891, a practice it had done since its founding.[44] Over the next couple of decades the once-ubiquitous “Holiness to the Lord” signs found on every ZCMI would quietly disappear.[45]

However, the desire for the Church to be associated with ZCMI resurfaced in the 1890s. George Q. Cannon raised the issue when he stated “that he had heard it frequently mentioned that the Institution was now looked upon by the people as a private corporation, and that there were no obligations to sustain it over and above any other private corporation,” which was true.[46] By that time, ZCMI had developed into a major department store and, in many respects, was not distinguishable in any significant way from the competing stores in Salt Lake City like Auerbach’s and Walker Brothers. In 1896, the Church decided to reinvest in ZCMI and bought $16,000 worth of stock and continued to buy more and more until by 1917 they owned about 11 percent; by the mid-1930s the percentage had grown to about 20–25 percent.[47] People who were not members of the Church were eventually allowed to own stock, and by the mid-1930s owned more than 25 percent of it.[48] It would take another half century for the Church to become the majority stockholder owning 51.7 percent of the stock, a surprising fact to many people given the popular perception that ZCMI was fully owned and operated by the Church.[49] The relationship that existed between the Church and ZCMI was best summed up by Arden Olsen in 1935 when he observed, “The Church does not control the business [of ZCMI],” but “indirectly if not directly the Church has considerable influence on the business policy.”[50]

From the late nineteenth century through the twentieth century, ZCMI developed much like other department stores in America. The downtown Salt Lake store was continually enlarged, covering a quarter of a city block, and became a shopping mecca, bookending the retail district for decades at Main and South Temple (Auerbach’s on 300 South and State Street being the other bookend). ZCMI became a grand emporium offering everything from groceries to wedding dresses to automobile tires.

Like other companies with wholesale and retail divisions, ZCMI abandoned its wholesale business in the early 1960s and started an aggressive expansion program of its retail operation. In 1962, a large store was opened at the first suburban mall in Utah, Cottonwood Mall, in southeast Salt Lake County, and a downtown store was opened in Ogden in 1967. The following decades saw stores open at Valley Fair Mall in Granger (now West Valley City) in 1970, at University Mall in Orem in 1972, at Cache Valley Mall in North Logan in 1976, at Layton Hills Mall in Layton in 1980, at South Towne Mall in Sandy in 1986, and at Red Cliffs Mall in St. George in 1987. Expansion also continued throughout the Intermountain Region with large stores in Chubbuck and Idaho Falls in the early 1980s and the introduction of ten “ZCMI II” (smaller concept stores carrying only higher-end clothing lines) stores in Utah, Nevada, and Arizona. ZCMI also completely rebuilt its flagship store with an adjoining mall in the mid-1970s. One notable feature was that ZCMI remained fiercely independent throughout the twentieth century when most independent stores were acquired or merged with other department store chains to survive.

By the time of its 125th anniversary in 1993, ZCMI appeared to be a vibrant company, a venerable Utah institution synonymous with Salt Lake City that had successfully weathered the vagaries of the twentieth century and, by all indications, was going to last for another hundred years.

The Demise

So why did ZCMI close? There were several contributing factors, some of which were decades in the making. Easily identifiable are the overexpansion, the declining sales, and the increased competition, but the ultimate deciding factor was the changing priorities of the Church in regard to its business interests.

The rapid expansion and ambitious building program taken by ZCMI proved to be financially imprudent. The Utah economy was really struggling in the late 1980s, and within a few years of opening the ZCMI II stores, all but two (at Foothill Village in Salt Lake City and Fashion Place Mall in Murray) were closed because of underperformance, and the failed concept ended up being a very costly venture. The demolition of the original flagship store in the 1970s (which, oddly, began shortly after a grand celebration of ZCMI’s 100th birthday) and the erection of an enormous, completely new flagship store, in retrospect, was ill-conceived; it had been expected that the downtown store would continue to be a shopping destination despite the fact that most shoppers were patronizing the suburban ZCMI stores more and more. The huge expense of capital was debilitating.

ZCMI also faced declining sales because of increased competition. ZCMI’s traditional competitor of over one hundred years, Auerbach’s, folded in 1981. But the void left by Auerbach’s was quickly filled with the arrival of retailers such as Nordstrom and Mervyn’s into the Utah market in the early 1980s. The retail landscape became even more diluted in the 1990s with national companies looking for new markets to exploit, and Utah was a perfect opportunity. Walmart and Target opened several big box stores, an outlet mall opened in Park City, and Arkansas-based Dillard’s opened four large stores in Ogden, Murray, Sandy, and Provo, which ended up being fierce competitors for ZCMI customers. The retail explosion that had been occurring across the United States had finally come to Utah, introducing an abundance of retail space. Utah shoppers were lured to the new stores, and it became difficult for ZCMI to compete.

The ultimate deciding factor in closing ZCMI, however, was the evolving relationship between the Church and its related businesses. From its earliest years in Utah, the Church had been involved in all kinds of economic enterprises, including hotels, sugar beet farms, hospitals, railroads, and publishing companies, to name a few. In many cases, the Church sponsored these endeavors because it was the only organization capable of doing so. As Utah and the Church grew and more business concerns were assumed by public and private entities, the necessity of Church involvement became less crucial and the Church liquidated interests in businesses like the Salt Lake Theatre and the Saltair amusement park, for example. Although the Church’s relationship with ZCMI had fundamentally changed in the late nineteenth century, the continued staffing of ZCMI leadership by the General Authorities indicated ongoing support.

The first indication that the relationship between ZCMI and the Church might not be maintained forever surfaced in the early 1960s when the Church divested itself of another prominent business concern, Zions Bank. In 1960 the Church sold all its 146,542 shares of stock in Zions Bank, which was also originally a cooperative venture founded by Brigham Young.[51] The First Presidency, under David O. McKay, explained the sale in a press release, indicating they had long considered the move and “that the best interest of the Church” would be served by getting out of the commercial banking industry.[52] The buyout offer, the release further explained, was “unsolicited and uninspired” but came at an opportune time. The sale of the bank, however, sparked a rumor that received national attention in a lengthy (and prophetic!) article that appeared in Women’s Wear Daily. The article stated that the Church was looking into liquidating its interest in ZCMI with the May Company as the potential buyer, as well as its interests in other businesses like the Hotel Utah and the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company.[53]

More than a decade later, the same issue resurfaced in 1974 when the First Presidency under Spencer W. Kimball announced that the Church would be divesting itself of its chain of hospitals, the stated reasons being that adequate healthcare was now available in Utah and, more noteworthy, that “the operation of hospitals is not central to the mission of the church.”[54] In issuing this statement, the Church had evidently developed a two-prong test that would be used in evaluating its continued support of for-profit businesses in subsequent years. The first prong appeared to be an evaluation of whether the business entity was providing a unique service or if it was duplicative of existing services available elsewhere. The second prong was whether such a business entity fit into the mission of the Church, which President Kimball would subsequently reiterate and popularize as proclaiming the gospel, perfecting the saints, and redeeming the dead.[55]

A second indication of the changing relationship between ZCMI and the Church came in 1975 when Kimball, who had become chairman of the board at ZCMI when he became President of the Church, declined to stand for reelection—he cited the heavy load of ministerial duties that required his attention.[56] The move was a bit surprising since every Church president since Brigham Young had served as president or chairman of the board. The role thereafter was assumed by a counselor in the First Presidency, N. Eldon Tanner, and then, beginning in 1980, was assumed successively by members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles Marvin J. Ashton and L. Tom Perry. In 1996, all General Authorities were removed from the boards of all businesses, including ZCMI, in order to focus more on ecclesiastical work.[57]

By the mid-1980s, ZCMI’s connection with the Church would come into question again. When the Hotel Utah was shuttered in 1987 to be renovated as the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, many assumed that ZCMI was next on the chopping block. The speculation was rampant enough that chairman of the board Marvin J. Ashton had to issue a very clear statement that there was no intention of closing ZCMI.[58]

Almost a decade later in the mid-1990s, amid the turbulent years of chronic department store closures and mergers across the country, ZCMI again made it clear in a press statement that it was not going to be bought out or to merge and would remain independent.[59] Behind closed doors, however, there was some concern about its survival. Ever since he had become president in 1990, Richard Madsen was charged with exploring various options for ZCMI and met regularly with Gordon Hinckley to discuss them.[60] Business then took a turn for the worse and profits started dropping precipitously in the mid-to-late 1990s with an $8.46 million loss in 1998.[61]

The declining revenue, naturally, forced a reexamination of the relationship between ZCMI and the Church. The Church, the majority shareholder with 51.7 percent of the stock,[62] appears to have been content with not interfering with ZCMI as long as it produced a profit. However, once it was no longer able to do so, the Church appears to have applied the two-pronged test as it had with other Church-related businesses.

ZCMI obviously failed the first prong of the test. As mentioned above, Utah had seen a dramatic increase in retail space in the 1990s and boasted a more than adequate selection of retail stores for its residents. The goods and services provided by ZCMI were not unique and were clearly duplicative of the merchandise provided by other retailers. Utah shoppers clearly did not need the Church to support a venue for them to buy clothing and domestic housewares.

ZCMI also failed the second prong of the test since it could no longer be justified under the threefold mission of the Church. It isn’t difficult to see the incongruity of a religious organization supporting an upscale department store while at the same time preaching from the pulpit scriptures in the Bible and Book of Mormon that decry the wearing of “costly apparel” (Alma 4:6) and chastise the daughters of Zion for their fascination with the world of fashion, as Isaiah does. Gone were the “Holiness to the Lord” signs, gone was the widespread ownership of stock among the general populace, and gone was the idea that patronage was part of the Lord’s work. What once had been seen as the means of establishing a Zion society had morphed into a fashion retailer.

But the fact that ZCMI did not support the mission of the Church is largely because the Church had completely abandoned ZCMI as a vehicle to establish Zion. As Leonard Arrington has pointed out, the Church’s welfare program has replaced what ZCMI was supposed to achieve in eventually preparing the Saints to live the United Order.[63] In fact, there was much speculation when the Welfare Plan was introduced in the 1930s as to whether it was just a new name for the United Order.[64] In the October 1942 semi-annual general conference, counselor in the First Presidency J. Reuben Clark spoke at length about the issue and stated that “in many of its great essentials, we have, as the Welfare Plan has now developed, the broad essentials of the United Order.”[65] A generation later another counselor in the First Presidency, Marion G. Romney, gave a speech at the general conference Welfare Services session reminiscent of Brigham Young’s exhortations about ZCMI. Romney declared:

We are living in the era just preceding the second advent of the Lord Jesus Christ. . . . The welfare program was set up under inspiration. . . . It is, in basic principle, the same as the United Order. When we get so we can live it, we will be ready for the United Order. You brethren know that we will have to have a people ready for that order in order to receive the Savior when he comes.[66]

The similarities in the original goals of ZCMI and the welfare program are evident: self-sufficiency, industry, working cooperatively for a common good, and the elimination of poverty. The emphasis of these values through the welfare program made the existence of ZCMI obsolete in achieving the goals of the Church.

By late summer of 1999, ZCMI was in negotiations to be acquired in a merger. Rumors were rife, but nothing was confirmed by ZCMI management. Church president Gordon B. Hinckley hinted of ZCMI’s imminent fate during the priesthood session of general conference in October 1999. In discussing the Church’s for-profit businesses, he stated that “we have divested ourselves . . . of these [businesses] where it was felt there was no longer a need.”[67] A couple of weeks later an announcement was made on 15 October 1999, that ZCMI would merge with St. Louis-based May Company in a deal valued at $52 million effective 1 January 2000 and would become part of the Meier and Frank division.[68] The announcement came as a surprise to many Utahns who never dreamed that ZCMI would just disappear.

Epilogue

The May Company continued to operate the ZCMI stores under that nameplate for two years after the sale. The merger agreement stipulated that the stores could not be opened on Sunday as long as they carried the ZCMI moniker in order to honor the commandment to keep the Sabbath day holy, a policy that had been in place since the store’s founding.[69] During the transition, the May Company changed the ZCMI logo by using a different font, liquidated ZCMI merchandise and lines, and started renovations on the stores. In 2001, the name change took effect and ZCMI officially became part of the Meier and Frank division of the May Company based out of Oregon. In 2005, the May Company was acquired by Federated Department Stores, and the Meier and Frank stores in Utah were replaced with Macy’s nameplate.[70]

Somewhat at competition are the Church’s desire to divest itself of businesses not central to its mission and its stated desire to keep downtown Salt Lake City, and in particularly the area around Temple Square, “attractive and viable.”[71] Retail is usually seen as the kingpin of holding a downtown together and so it is interesting that the Church decided to pull its support from ZCMI and then, a few years later, move forward with one of the most (if not the most) expensive luxury retail developments of the decade in the United States, costing an estimated $1.5–2 billion.[72]

Following the 2002 Olympic Games in Salt Lake City, a huge redevelopment of the two downtown Salt Lake City malls was announced with the Church’s real-estate arm partnering with Taubman Centers, Inc., an upscale mall developer based in Michigan. The Church, which already owned the ZCMI Center, acquired Crossroads Plaza, which was situated directly west across Main Street. The concept was to redevelop the two malls into one under the name City Creek Center, which would be owned and managed by Taubman. As part of the decade-long redevelopment, the façade of the original ZCMI store (fortunately preserved during the 1970s rebuild) was reinstalled in its historic location on the front of the new building that currently houses Macy’s. Under the pediment, the iconic letters of ZCMI were lit up with medallions on either side with the founding and dissolution dates 1868 and 1999. Though the original store and the company are now just memories, the façade stands as a striking monument to Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution.

Notes

[1] A Book of Commandments, for the Government of the Church of Christ, Organized according to the Law, on the 6th of April, 1830, Zion ([Independence, Missouri]: W. W. Phelps, 1833) , chapter XLIV, verses 26–29, 33, pp. 92–93. In the modern edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, these verses are found in section 42:30–36, 40, in modified form.

[2] Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 19–20.

[3] “Public Meeting,” Nauvoo Neighbor, 13 March 1844, [2].

[4] Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God, 88–89.

[5] Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and Jedediah M. Grant, “Eleventh General Epistle, of the Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, to the Saints in the Valleys of the Mountains and those scattered abroad through the Earth, GREETING—,” Deseret News, 13 April 1854, [3].

[6] Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God, 78.

[7] Young, Kimball, and Grant, “Eleventh General Epistle,” [3].

[8] Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God, 111–34.

[9] George Q. Cannon, “President Young’s Trip North” (quoting Brigham Young’s remarks delivered 19 August 1868), Deseret News, 26 August 1868, [5].

[10] “Supply and Demand—Class Interests,” Deseret News, 26 July 1866, [4].

[11] G. D. Watt, “Remarks, by President Brigham Young at the General Conference, G. S. L. City. Oct. 9th, 1865,” Deseret News, 2 November 1865, [2].

[12] Arden Beal Olsen, “The History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation in Utah” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 1935), 36–38.

[13] “A Card. To the Leaders of the Mormon Church,” Daily Union Vedette, 22 December 1866, [2].

[14] Brigham Young, “Reply,” Deseret News, 2 January 1867, [1].

[15] “The First Victims of the Crusade,” Daily Union Vedette, 28 December 1866, [2].

[16] Leonard J. Arrington, “The Transcontinental Railroad and Mormon Economic Policy,” Pacific Historical Review 20 (May 1951): 153–54.

[17] “Co-operative Wholesale Store,” Deseret Evening News, 10 October 1868, [2]; “Local and Other Matters,” Deseret Evening News, [3]; “Local and Other Matters,” Deseret Evening News, 16 October 1868, [3]; and Record [Book] A, pp. 12–13, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[18] “Local and Other Matters,” Deseret Evening News, 14 November 1868, [3].

[19] Record [Book] A, p. 33, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[20] Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1892), 1:287.

[21] Record [Book] A, p. 40, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[22] “Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution” [advertisement], Deseret Evening News, 10 March 1869, [2].

[23] “Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution” [advertisement], Deseret Evening News, 21 April 1869, [2].

[24] Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 127.

[25] “Here and There,” Deseret Evening News, 12 April 1869, [3].

[26] Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 131.

[27] For a fairly complete list of the independent ZCMI stores, see Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 130–33.

[28] PH 364 and PH 3807, Church History Library. These two photographs are views of Deadwood, South Dakota, circa 1876 with a ZCMI sign clearly visible on one of the buildings. It has not been confirmed if there was indeed a ZCMI store there or if there is an alternate explanation for the ZCMI sign being present.

[29] Record [Book] A, p. 68, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[30] Record [Book] B, p. 49, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[31] David W. Evans, “Remarks by President Brigham Young delivered in the New Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, April 7th, 1868,” Deseret News, 2 June 1869, [7].

[32] David W. Evans, “Remarks by President Brigham Young delivered in the New Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Oct. 8th 1868,” Deseret News, 11 November 1868, [2].

[33] “Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution. Constitution and Bylaws” [circular], Salt Lake City, Utah: Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution, [1868?], sections 1, 20, 28, and bylaw 1. Several of these spiritual characteristics of the constitution were noted by Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 87–89. It has also been noted by Olsen and Arrington that ZCMI was never a cooperative in the true sense of the word but really more like a corporation in terms of organization. It was, however, cooperative in its purpose and mission to provide wealth distribution among its members and better the communities where it operated.

[34] David W. Evans, “Remarks by Brigham Young delivered in the New Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, April 8th, 1869,” Deseret News, 16 June 1869, [8].

[35] Record [Book] A, p. 40, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[36] G. D. Watt, “Remarks by President Brigham Young, in the Tabernacle, in Great Salt City, Sunday, 23 December 1866,” Deseret News, 9 January 1867, [3].

[37] CR 100 1 Historical Department Office Journal, 1844–2012; 28 November 1868, vol. 30, p. 95, Church History Library.

[38] Lars Fredrickson, History of Weston, Idaho, ed. A. J. Simmonds, Western Tract Society Number 5 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1972), 20–21, 24. Fredrickson’s manuscript for this story can be found in MS 11108, box 3, folder 3 [5], Church History Library.

[39] CR 100 1 Historical Department Office Journal, 1844–2012; 22 May 1869, vol. 30, p. 194, Church History Library.

[40] Brigham Young, George A. Smith, et al. [First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles], “Zion’s Co-operative Mercantile Institution,” [circular], 10 July 1875, 3.

[41] John Taylor, in Conference Report, April 1880, 74.

[42] John Taylor, “An Epistle to the Presidents of Stakes, High Councils, Bishops and Other Authorities of the Church,” [circular] Salt Lake City [The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints], 1 May 1882, 3–4.

[43] ZCMI Stock Transfer [Book] A, certificate dated 11 March 1886 showing 3,500 shares of stock transferred to Heber J. Grant and Company by John Taylor, Trustee-in-Trust of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library, and Olsen,

History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 196–97.

[44] ZCMI Record [Book] D, p. 218, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library, and Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 198–99.

[45] Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 139.

[46] Record [Book] D, pp. 138–39, MS 16486 Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution records, Church History Library.

[47] ZCMI Stock Ledger and Olsen interview with ZCMI secretary-treasurer Harold H. Bennett in circa 1935, as quoted in Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 213.

[48] Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 215.

[49] Max Knudson, “May Agrees to Buy ZCMI: Store in Downtown S.L. to Remain Closed on Sundays,” Deseret News, 15 October 1999, A1.

[50] Olsen, “History of Mormon Mercantile Cooperation,” 215.

[51] “Zions National Bank Sold to Businessmen,” Deseret News–Salt Lake Telegram, 22 April 1960, A1.

[52] “First Presidency: Text Explains Action in Sale of Bank,” Deseret News–Salt Lake Telegram, 22 April 1960, A1.

[53] Lloyd Schwartz, “Mormons Spike Rumor ZCMI Up for Sale,” Women’s Wear Daily, 22 June 1960, 2.

[54] “Church Divests Self of Hospitals,” Deseret News, 14 September 1974, Church-3.

[55] Spencer W. Kimball, “A Report of My Stewardship,” Ensign, May 1981, 5. Although Kimball popularized the mission statement, he did not originate the concept. The threefold mission of the Church had been articulated at least a generation earlier by John A. Widtsoe in Program of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: Manual for the Senior Department of the M.I.A. (Salt Lake City: General Boards of the Mutual Improvement Association of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1938), 123–24.

[56] “First Presidency Amends Policy on Corporations,” Deseret News, 7 June 1975, Church-14.

[57] “LDS General Authorities to Withdraw from Boards,” Deseret News, 18 January 1996, B1.

[58] Marvin J. Ashton and L. Tom Perry, “We Stand Loyal to ZCMI,” Associate Press [ZCMI employee newsletter], May 1987, 1.

[59] “ZCMI Says It Is Absolutely Not for Sale,” Deseret News, 15 August 1995.

[60] Interview with Brent Parkin (Richard Madsen’s son-in-law) by author, 31 January 2019.

[61] ZCMI Annual Report 1998 (Salt Lake City: Zion’s Cooperative Mercantile Institution, 1998), 1.

[62] Knudson, “May Agrees to Buy ZCMI,” A1.

[63] Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God; see chapters 15 and 16 for an in-depth discussion.

[64] Arrington, Fox, and May, Building the City of God, 344.

[65] J. Reuben Clark, in Conference Report, October 1942, 58.

[66] Marion G. Romney, “Growth of Welfare Services,” Welfare Services session, in Conference Report, April 1975, 165–66.

[67] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Why We Do Some of the Things We Do,” Ensign, November 1999, 53.

[68] Knudson, “May Agrees to Buy ZCMI,” A1.

[69] Knudson, “May Agrees to Buy ZCMI,” A1.

[70] Jenifer K. Nii, “Meier & Frank Soon to Get New Name: Macy’s,” Deseret News, 29 July 2005.

[71] Hinckley, “Why We Do Some of the Things We Do,” 53.

[72] Joel Kotkin, “Salt Lake City’s Sacred Space,” Forbes, 29 June 2010. Jasen Lee, “$1.5B City Creek Center on Schedule for March 22 Opening,” Deseret News, 27 January 2012. Alice Hines, “City Creek, Mormon Shopping Mall, Boasts Flame-Shooting Fountains, Biblical Splendor,” Huffington Post, 23 March 2012.